Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 1

Women at Work and Business Leadership Effectiveness

Sherrie Pafford, Capella University

Thomas Schaefer, Capella University

Keywords

Business Leadership, Work Effectiveness, Leadership Effectiveness, Gender.

Introduction

Regardless of the relationship that exists between gender and societal roles, there is still a disconnect into how they function in a business environment. There is a struggle to understand what characteristics women need to possess and model to be successful leaders. In August of 2016, women filled only 19.9% of board positions, with 4.6% being Chief Executive Officers (CEOs; Catalyst, 2016; Warner, 2014). The percentage of women in executive manager roles has only had minor changes over the past 40 years, from 5% in the 1970s to 14% in the 2014 and 19.9% in 2016 (Schein, 1973; Warner, 2014; Catalyst, 2016). Estimates indicate that given the rate of change in management positions, it will be 2085 before women reach parity (Warner, 2014).

This is contrary to articles posted as recent as January 16, 2017 in the Washington Post, where Sallie Krawcheck talks about what women can do to improve their careers (McGregor, 2017). Krawcheck believes that women should not be more like men and continue to bring their relationship skills, collaboration and deliberative decision-making approaches to the work environment (McGregor, 2017). Telling women to be themselves in the workforce is contrary to years of the think manager-think male paradigm toted since the 1970s (Schein, 1973).

Krawcheck pushes the envelope and wants women to question the pre-established societal roles that favour masculine characteristics over feminine characteristics for managerial positions. However, historical trends show an apparent notion that there is a perception of women to be less effective leaders when adopting male characteristics (Coder & Spiller, 2013; Duehr & Bono, 2006; Gherardi & Poggio, 2001; Ingols, Shapiro, Tyson & Rogova, 2015; Schein, 1975). An examination of the movement in gender perception of women in leadership roles adopting male characteristics (i.e., agentic) due to societal changes can guide and update business practices (Duehr & Bono, 2006; Ransdell, 2014).

Females in corporate leadership make up a small but important subset of the larger population of women within business. Both male and female managers perceived men to be more likely to have the characteristics associated to be successful managers, which supports the concept that acting male in leadership positions garners better support and following (Schein, 1973; Schein, 1975). Women are faced with a unique challenge when in management positions because they are viewed negatively when adopting perceived male characteristics that help in leadership and management success (Brandt & Laiho, 2013; Eagly & Karau, 2002).

To add to Krawcheck’s national conversation on women in the professional world, the understanding of role congruity theory is paramount to access change. Role congruity posits that perceptions that are more favourable exist when the characteristics an individual exudes closely align with the social roles assigned to the group/gender (Eagly, 1987). Women have become more androgynous in leadership style while men have changed very little (Snaebjornsson & Edvardsson, 2013). Think manager-think male appears to be in direct opposition to social and role congruity theories. Gender stereotypes can be damaging to women since masculine stereotypes are considered more essential to management/leader success but judged more harshly when utilized (Brandt & Laiho, 2013). Thus, women who espouse stereotypically male characteristics face preconceptions because incongruities arise between the characteristics linked with the gender and those linked to societal role or gender stereotype (Eagly & Karau, 2002) leading to inauthenticity and breakdown of effective leadership.

The extent leadership effectiveness is linked to gender is not known. For several decades, studies on gender perceptions and differences in leadership have been conducted in business. However, the questions focus on whether there are key differences in the perception of women and men as leaders (Duehr & Bono, 2006; Schein, 1973). Not knowing the extent to which leadership effectiveness and gender are linked is due to the unequal representation of females in upper-level management positions (Ignatius, 2013). Additionally, business managers continue to define senior management roles in masculine terms (Heilman, 2001; Kyriakidou, 2012). Research is deficient in ascertaining what characteristics are deemed needed by women to be successful as leaders. However, there is conflicting information about perceptions of characteristics adopted by women to try to be successful in leadership positions.

Sheryl Sandberg, the Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, noted the specific problem for women is the likability gap (Ignatius, 2013). The likability gap shows how there is a positive association for men and a negative one for women when adopting stereotypically masculine traits in management positions (Ignatius, 2013). The problem skews farther when the societal roles, identities and behaviours keep changing and no longer align with preconceived perceptions (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Ignatius, 2013). Personal characteristics, both innate as well as learned, influence the strategic choices of senior executives as demonstrated in Hambrick & Mason’s (1984) seminal work on the upper echelon theory. Innate characteristics would include cognitive based capabilities as well as values, while learned characteristics would include education, career experience and socioeconomic background, to name a few.

In a 2014 interview with PepsiCo CEO, Indra Nooyi, she stated “I don’t think women can have it all” (Friedersdorf, 2014). She continued with “We pretend we have it all” (Friedersdorf, 2014). Every day there is a balance where women have to decide on job, wife or mother. It is difficult to join other mothers and be in a meeting when groups meet during business hours. In addition, Nooyi has said women have to find a way to cope with the guilt of not being able to have it all or women will die from the guilt of it (Forbes, 2014). A major problem is that the career clock and biological clock are at constant odds with each other and to be good at one you have to forfeit the other (Forbes, 2014). Sheryl Sandberg, the Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, dedicated a whole chapter in Lean In (2013), as to how the myth of having it all is a detriment to men and women, but especially women as it appears we fall short in both work and home life balance.

Role Congruity Theory

Eagly & Karau (2002) developed a theory addressing the prejudice toward females as leaders or more succinctly role congruity theory. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders (a.k.a., role congruity theory) proposed that the incongruity between the societal role assigned to women and those characteristics assigned to leaders created a prejudice against female leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002). Eagly’s (1987) social role theory was the root of Eagly & Karau’s role congruity theory, in that it maintained that societies cultivate descriptive and prescriptive gender role perceptions of individual’s behaviour due to the social gender roles they are presumed to fill and emulate. Heilman (2012) said it very distinctly: Descriptive equals what women and men are like and prescriptive equals what women and men should be like. Men have traditionally filled higher status, breadwinner roles which often times require agentic behaviours and characteristics like being assertive, aggressive and independent, while women have historically filled lower level, caregiving roles, which require communal characteristics like being sympathetic and nurturing (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Karau, 2002). Simply stated, males are believed, expected and perceived to possess more agentic traits than women and women are believed, expected and perceived to be more communal than men. Eagly & Karau added the layer of leadership roles to social role theory to expand the understanding of how the differences in perception lead to prejudice and the moderators that can influence congruity perception.

Role congruity theory contends that there are differences in the perceived lack of congruence of females in leadership roles, because of stereotypes applied to women or due to job definitions that leverage male gender terms, should in turn influence the degree and frequency of gender bias that results. Gherardi & Poggio (2001) stated how organizational cultures are not genderless and therefore do not define things as genderless. In fact, quite the opposite can hold true. Businesses will provide specific gender characteristics to a role or position and often times it is ambivalent or contradictory to women’s societal roles (Gherardi & Poggio, 2001). Women are rated more favourably and perceived to be more effective leaders when leadership roles and gender societal roles are congruent (Brandt & Laiho, 2013). However, harsh ratings surface when women use autocratic styles and/or manage similarly to male counterparts (Brandt & Laiho, 2013). The immense body of literature analysing gender and leadership offers other hypotheses that differentiate from some of the role congruity theory’s hypotheses regarding which moderators play a role in gender differences of leadership effectiveness (Eagly & Karau, 2002). An example of a different moderator is personality (Brandt & Laiho, 2013).

Note that men also receive disapproval when not following the societal and business norms that belong to men and leaders; however, it is not as detrimental to work evaluations, perception of job success or follower mentality as it is for women (Heilman, 2012). When men ask for family leave or work life balance, they are seen to not have the same work ethic as other male employees and if in a field that is stereotypically a women’s job they are deemed wimpy and passive (Heilman, 2012). Nevertheless, men still hold a comparative advantage and are evaluated less harshly and “men continue to benefit from being men, even in female work settings” (Heilman, 2012).

Eagly & Karau’s (2002) role congruity theory demonstrated the significance of how well gender roles and leader roles need to fit in regards to the traits associated and adopted for assigned roles. According to role congruity theory, business areas that are male dominated or defined by society as masculine present certain trials to females because of the incongruity with society’s expectations of females. Military leadership positions are a robust example of defining positions in masculine terms (Brandt & Laiho, 2013; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Schein, 1973; Heilman, 2012). This incongruence restricts women’s access to male dominated business industries. Eagly & Karau (2002) & Heilman (2001) discussed when leadership roles are defined in masculine terms and made-up of predominantly men, individuals may perceive that females are not qualified for those industries and roles and they may struggle with females in authority positions. There are industries perceived as less masculine and in recent years have seen increases in hiring of more women than men (e.g. educational fields; Ways & Marques, 2013). One theme in role congruity theory is the extent to which industries utilize gendered terms (Eagly & Karau, 2002).

Gender

Gender stereotypes continue to exist, as women are still undervalued compared to men, unless the quality of the work output is irrefutable and that there are subjective indicators when comparing output in the office between the genders (Heilman, 2001). The expectations are prejudiced from the outset and that leads to misapplication and interpretation by organizational members in regards to performance and reviews (Heilman, 2001). Katila & Eriksson (2013) conducted a study using empathy-based stories to see the gendering of outcomes of managerial roles. By personifying the agentic characteristics (i.e., decisive, aggressive, competitive) society may have skewed roles as those characteristics are heavily associated as masculine (Duehr & Bono, 2006; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Katila & Eriksson, 2013; Schein, 1973; Ingols et al., 2015). Meaning historically there was a time when there was a clear split of the labor force based upon gender (Ingols et al., 2015). Women were caregivers at home and paid jobs belonged to men.

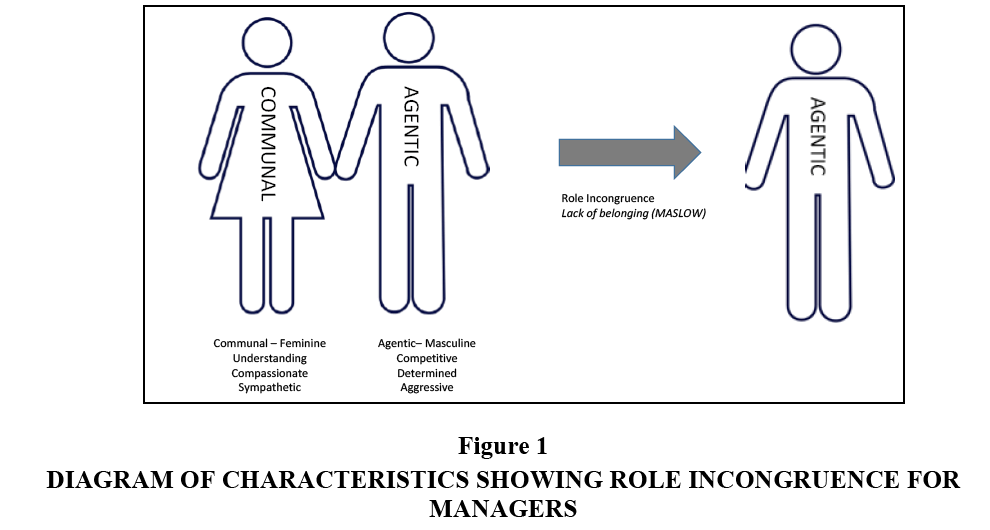

Therefore, gender stereotypes are damaging to women in leadership roles due to masculine characteristics being perceived to be more essential than feminine traits (Brandt & Laiho, 2013). All managers and leaders need to have agentic characteristics to be successful in business. However, when men act agentic it is congruent to their societal role and they are rewarded (Ingols et al., 2015). When women act agentic; this is incongruent to their societal role and they are received negatively and not seen as a leader (Ingols et al., 2015).

How Did We Get Here?

Any discussion of leadership and gender stereotypes should begin with the seminal work of Virginia Ellen Schein (1973). Previous research by Broverman, Broverman, Clarkson, Rosenkrantz & Vogel (1970) focused on masculine and feminine stereotyping but did not further its application in the business world. The social identities of men and women were distinct and separate, demonstrated that societal norms anticipate and predict the existence of certain traits in each gender (Broverman et al., 1970). Schein took the application a step further and applied 92 gender specific traits to a study on what a manager is (Schein, 1973). Schein (1973) was able to coin the phrase think manager-think male from her study and was able to start to answer whether men were seen/perceived as more successful in managerial roles.

Broverman et al. (1970) described women in Western culture as rapidly changing and this causes intense conflicts between customs and traditions historically rooted in the past. Women were once stay at home mothers, are now becoming CEOs (Ingols et al., 2015). In the corporate world, the conflict includes the struggle between the ambitious ideas of gender parity and advancement for all and the social stigma that limit roles requiring agentic characteristics of men (Alewell, 2013; Brandt & Laiho, 2013; Broverman et al., 1970; Ingols et al., 2015; Koenig, Eagly, Mitchel & Ristikari, 2011). In the 1980s, the phrase glass ceiling introduced a metaphor for the invisible barrier that kept women from moving up the corporate ladder and advancing in careers (Johns, 2013). The previous statistics (i.e., women filling only 19.9% of board positions, with 4.6% being CEOs) show how the glass ceiling metaphor is still in place and holding strong (Catalyst, 2016; Warner, 2014). The glass ceiling metaphor was also used in the concession speech of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential race in regards to how in the United States women have not shattered the “highest and hardest glass ceiling” (Hillary Clinton, 2016) in regards to the Presidency. One consideration to the glass ceiling barrier to this day is the perceptions of think manager-think male paradigm. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly more important to consider research and societal role definitions. Eagly & Karau (2002) posited traditional gender identities affect both the choices accessible to females in the business world and the choices females make from those existing options. Incongruity between leadership characteristics is shown in Figure 1 and those applied to female characteristics is not static or motionless, but fluctuates drastically with a variation in either stereotype (Alewell, 2013; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Koenig et al., 2011).

Over 20 years later, the think manager-think male paradigm is still prevalent. In 1994, the definition of a successful manager was still promoting stereotypes and still defined in masculine terms and characteristics (Ingols et al., 2015; Still, 1994). Women in leadership roles were making choices seen as disingenuous to their gender in order to be perceived as a successful manager or leader (Ingols et al., 2015; Still, 1994). Both men and women perceive that successful middle managers should possess specific traits and viewed those traits needed as more masculine than feminine (i.e., agentic over communal; Duehr & Bono, 2006; Adbel & Elsaid, 2012; Ingols et al., 2015; Schein, 1973). Orser (1994) conducted a study showing the masculinization of managerial positions was incongruent to the characteristics of females. Gherardi & Poggio (2001) further showed similar results that women operating in a manner that is inauthentic to societal roles and adopting masculine characteristics create a double bind for women. The definition of the double bind is when women act like managers using agentic characteristics ascribed to men, at the cost of violating gender role expectations and being perceived as inauthentic (Gherardi & Poggio, 2001; Ingols et al., 2015). Women received derogatory titles such as “barracudas” (Still, 1994) and “battle-axes” (Still, 1994) when adopting the ruthless, aggressive and task-orientated characteristics associated with successful management, but also most often associated with their male counterparts. “Dragon lady, ice queen and battle axe” (Heilman, 2002) were still descriptors used twenty years after think manager-think male became the predominant business paradigm for women. The disconnect of qualities, traits and characteristics of women and leaders, create a double bind and lead to a double standard in leadership roles (Ely, Ibarra & Kolb, 2011). Women still endure pejorative titles such as “abrasive, arrogant or self-promoting” (Ely, Ibarra & Kolb, 2011).

Karp & Helgo (2009) described developing one’s persona by identifying different and discrete social roles a person has and being true to one’s self in those roles at any period and being able to react authentically. Reactions differ due to stimuli that may not have been present in previous moments. Eagly & Carli (2007) demonstrated that female leaders do not always translate and equate due to the social identity characteristics of each group not necessarily aligning.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is how individuals within an organization relate to each other (Schein, 1992). There is within-group alignment and group-organization alignment (Bezrukova, Thatcher, Jehn & Spell, 2012). In other words, subcultures are distinct to a business area within a company (Schein, 1992; Bezrukova et al., 2012). Schein (1990) also contributed that culture is learned. Therefore, to understand better cultural development, learning models are vital. Culture formation is learned by and mostly passed down to trainees made new hires from, the veteran members within the company (Bezrukova et al., 2012; Drath, 2001). Company leaders and their values and behaviors help the company succeed (Brown & Trevino, 2006). The values and behaviors become the company’s DNA (Kotter, 2012; Stomski & Leistein, 2015). The review of the literature showed an assortment of methods to defining and understanding organizational culture.

In the 1990s, organizational culture was a relatively recent concept (Schein, 1990). Although used in a variety of ways and dealing with numerous problems, how organizational cultures became organizational development and management needed to be more closely studied (Schein, 1990; Schein, 1992). Organizational cultures are a set of customs and ideals that are widely known, shared and strongly held by the corporation (Bezrukova et al., 2012; Schein, 1990). According to Schein (1990), there are three levels to building corporate culture: Artifacts, basic values and underlying assumptions. There is a progression of group development experienced over four stages: Forming, storming, norming and performing (Tuckman & Jensen, 2010). (Schein, 1992; Bezrukova et al., 2012) described how leaders and founders operate at various levels to create, shape and define organizational culture. Both organizational culture and individual group culture (i.e., subculture) contribute to the overall corporate culture

Founders and leaders of companies create and define the culture from the onset of establishing their business (Day & Antonakis, 2011; Kuppler, 2014). However, there is no agreed upon definitions for leadership or culture (Day & Antonakis, 2011; Dickson, Den Hartog & Mitchelson, 2003; House, Javidan, Hanges & Dorfman, 2002). A 2014 study, reiterates Virginia Ellen Schein’s 1973 study and comments that culture and leadership are the two sides of the same coin and that culture, not personality, is what drives leaders (Kuppler, 2014). Leaders need to ensure that workforce and company cultures are growing culturally diverse (Day & Antonakis, 2011). Leaders also need to be aware that company culture and diversity are not the same in every cultural situation or company context (Day & Antonakis, 2011). Leaders should focus on solving problems and not put the primary focus on changing culture (Kuppler, 2014). Striving to change culture is extremely difficult, especially since culture permeates every aspect of the core of a person, business and society. Edgar Schein (1990) described organizational culture as group behaviour learned over a period of time, which responses to problems solved develop exterior adaptation and interior integration. Schein (1992) discussed how leaders could manipulate organizational cultural development through control and reward, role modelling and coaching and selection and promotion. The workforce sees the emerging culture and, stabilized by these events, for better or worse, adjusts effort and time to traditions and beliefs (Schein, 1992). The more engrained these traditions and beliefs become, the more group participants take them for granted. Schein (1992) continued that corporate culture starts out as founder and leaders values, but turn into assumptions as they persist over time.

Similar to (Schein, 1992; Van Wart, 2013) also ascertained companies need to evolve and change to match leadership trends and corporate culture. Theories and policies need to be updated, revised and adhered (Van Wart, 2013). Leaders are a factor to organizational success and ensuring that the message of the leader aligns with the company goals will then help project a unified message in the corporate world. To reiterate, as times have changed so have the leadership theories to be studied and applied (Van Wart, 2013).

Schein (1992) describes organizational culture as socially entrenched, socially created and replicated over time. Organizational culture develops exactly like all social paradigms, in that it is not static, but is the repeated actions, ideologies and beliefs played out repeatedly by a group. Translation is that organizational culture, much like societal norms, is dynamic and evolving, due to the constructs and paradigms tested and applied continually by the group. The core foundations of the social group are the aspects of the emerging culture that are least pliable (Schein, 1992). The organization (i.e., personnel and procedures) needs to be well-integrated into the corporate culture to allow the business to obtain a competitive sustained advantage through cultural potential, which assures flexibility and ability to respond adequately to social and environmental changes (Schmitz, Rebelo, Gracia & Tomá, 2014). Organizational culture also creates processes by which supervisors and leaders can respond to an ever-changing environment while preserving and sustaining organizational stability. Organization culture drives the activities of the business, by transferring learning from the individual to the collective (Schmitz et al., 2014).

Experience

Historically, past management practices of several businesses focused on promoting males into executive and senior leadership roles and Adler’s (2002) study suggested it has been challenging for businesses to change their leadership advancement and development programs to include both males and females. In some ways, this is not surprising because laws giving women equal pay and employment opportunities have only existed in industrialized nations for the past forty years (Adler, 2002; Alonso-Almeida, 2014; South worth, 2014). Inadequate compensation policies, training and leadership development programs and opportunities for advancement and promotion, contributed to the slow change to gender diverse leadership teams, rather than the previous male-dominated executive teams (Oakley, 2000). When organizations inadequately prepare women for senior leadership and management roles, the advancement and promotional opportunities processes discount them. Women rarely receive an opportunity to work in international management and expatriate experiences and those experiences are beneficial in placement in the global marketplace and in different cultures and leadership advancements (Oakley, 2000).

Being able to find balance between work and home helps to create not only authentic leaders but also create authentic people. DeLaine-Hart’s (2009) research supported much of what Nooyi stated. Women, albeit highly educated and well qualified, do not have the same chances to advance without conceding and losing other very important parts of their lives. One aspect is losing oneself and adopting and demonstrating male traits and forsaking the feminine ones. As Eagly & Karau (2002) stated, by adopting aspects that are not in societal DNA, one is seen as inauthentic and less apt to be followed or can be prejudiced against. A qualitative study, utilizing interviews, took a closer look at nine women in local government executive positions (DeLaine-Hart, 2009). The results of the interviews revealed that in order for women to be successful in leadership they needed to overcome barriers, to include finding balance between family and work (DeLaine-Hart, 2009).

Organizational culture defines acceptable behavior in a firm by functioning as an informal control mechanism or barrier. Organizational culture also defines the employee (Waters, 2004). Organizational culture and gender stereotyping must be studied together to comprehend how leadership and management are realized (Heilman, 2012).

By studying organizational culture and the limitations that the culture institutes, control mechanisms commanding the status quo can be made obvious and can enlighten employees as to why there is still not equality in senior leadership and management roles. A better understanding of the limitations also helps establish the continual uphill climb for women to achieve success in business. A key paradigm is that organization culture is an all-encompassing corporate culture in which value congruence and support of individuals share norms and values (Bezrukova et al., 2012). To allow for congruent alignment to subgroups and adhere to similar attributes in society and business, individuals need to be true to themselves in any given work environment. Organizational culture remains a central theme when examining the experiences of female leaders and managers.

Work-Life Balance

The workplace is starting to recognize the needs of personnel as they are struggling to balance the requirements of their work life with the requirements of their home life. “Two days aren’t enough to make up for a life unlived the other five,” (Begun, 2017). The present atmosphere in business is that employees are parents with families or care for elderly family members. Business can profit from being cognizant of home life matters that can add stress and provide a workplace that is sensitive to the precarious balancing of work and home lives (Marche, 2013; Silver, n.d.; Schwartz, 1989). While not related to gender stereotyping, women’s decisions to focus on family and not career could definitely present a reason for the lack of women in senior leadership in a variety of settings (Ransdell, 2014). In a study of women leaving the sciences, engineering and technology industries, Hewlett, Luce & Servon (2008) calls work-life balance for companies the “fight or flight moment” (p. 23). Women scientists, engineers and technologists feel strong conflict between earning promotions and maintaining a family life (Hewlett, Luce & Servon, 2008). Many women chose not to continue in their respective fields because the demands on family life were growing too great to overcome. Hewlett, Luce & Servon (2008) noted that flexible working hours, to include part-time work, were detrimental to success and growth in leadership positions.

Traditional roles of women, inside and outside of the workforce, show that women are still doing the predominant amount of domestic work outside the home while working and looking to move up the career ladder (Ingols et al., 2015; Schwartz, 1989). The Department of Labor showed an average working female spends about twice as much time as the average working male on household chores and childcare (Wiehl, 2007). Even in two-income homes, women still endure the most of running the household (Hewlett, Luce & Servon, 2008). Businesses can circumvent losing talented personnel by providing other options that allow for a balance of both worlds by investing in their employee’s well-being in either work from home arrangements (i.e., virtual) or flexible schedules (Alonso-Almeida, 2014; Silver, n.d.). A company’s goal is to maintain and preserve a talented workforce and have their personnel be successful in all facets of their lives. Employees should not have to suffer and cause undue burdens and strain where breakdowns, health or drastic changes occur for a healthy happy home and work life balance (Alonso-Almeida, 2014). The myth that one can have it all and be a great working parent without sacrifices is far from true and men being the breadwinner and needing to hold that burden can transform with work-life balance policy changes (Marche, 2013; Southworth, 2014).

Missing from the conversation is the male’s voice or side of the equation. Marche (2013) noted how even though businesses see women as the main caretaker in a family, women do not decide who takes care of the children, how to manage money or other family matters by themselves. Although society may have an overarching opinion, that it is the family unit (parents) that decide such home matters and that it truly comes down to family versus money, not that women are primary caretakers (Marche, 2013).

Even with the legal, political and corporate pressures think manager-think male endures and outdated gender biased paradigms prevail. One such assumption/paradigm is that there are worldwide factors and barriers to women, such as needing friendly family policies to help eliminate restrictions of work for women that have to balance career and family (Alonso-Almeida, 2014). There is pejorative association to both men and women that appear to need to ask for time off, however there is more inequity towards women utilize (if available) or request (if unavailable) for concessions to help facilitate work life balance (Southworth, 2014). The negative association is echoed when high attaining women (and some men) managers, even when businesses provides family friendly policies and programs, fear that taking such aide would be damaging to their careers (Alonso-Almeida, 2014; Heilman, 2012). By not challenging the assumption or accepting the aide, managers are helping perpetuate the stereotype that it is a man’s world (Southworth, 2014) and allows think manager-think male to have a strangle hold on business culture (Heilman, 2012; Schein, 2007).

Leadership Effectiveness

The theories of leadership are as varied as the definitions of leadership (Fiedler, 1971). A definition that resonates most closely with leadership effectiveness is the concept that a leader influences more than his is influenced (Drath, 2001). An exchange of information can occur between leaders and followers, but knowledge, direction and vision should trickle-down from the leader. Leaders are responsible for the exchange after information is gathered and processed. The same is true for defining leadership effectiveness. Studying leadership effectiveness collectives or interdependencies helps leaders and managers achieve common goals (Cullen, Palus, Chrobot-Mason & Appaneal, 2012). Effective leadership is a leader’s ability to help a group meet its goals and maintain itself over a period of time (Drath, 2001). Leadership effectiveness therefore is the result of leaders' behaviours rather than a particular type of behaviour (Van Wart, 2013). Trust and mutual understanding are key components in building business relationships and working groups (McCallum & O’Connell, 2009). Trust is imperative to build and foster relationships and cooperation. Learning how to be part of a team, respectful of others and yes, building on trust from the onset, are all key components of how leaders can make an organization more effective.

The outset of a business relationship is a crucial moment for the development of trust (Miles, Coleman & Creed, 1995); gaining trust early among employees shows trust is based on a person’s willingness to trust others as well as on situational context (Miles, Coleman & Creed, 1995). Trust is as an attitude held by one individual toward another, in other words a trust or/and trustee (Miles, Coleman & Creed, 1995). The expectation of trust in people is the expectation that all parties’ actions will be based on good intentions for the group as a whole. Research on leadership and organizational needs has shown that workgroup members have different relationships with the work group leader (Schein, 1978).

Leadership effectiveness also includes having the team, from the onset, being part of the solution and not dictated to makes everyone a responsible member of the team (McCallum & O’Connell, 2009). Every member can have moments of leadership to ensure the success of the group. Roberts, Dutton, Spreitzer, Heaphy & Quinn (2005) stated that being extraordinary is very simple, just “being true to self” (p. 712). Shakespeare may have said it best in Hamlet “to thine own self be true.” Realizing that the power to be extraordinary is not in anyone else’s hands or actions, but oneself is a powerful piece of knowledge. Knowing that others opinions can shape this makes complete sense as needing social interaction is one of Maslow’s hierarchal needs (i.e. belongingness) or there would be a failure to thrive (which would be in direct opposition to evaluating one’s success; Lester, 2013).

By being true to one’s self, as well as trying to ensure belongingness, there is a balance between authenticity and ethical leadership (Brown & Trevino, 2006). Ethical leadership proscribes leaders to act on traits that are moral, truthful and kind (Brown & Trevino, 2006). Scharmer (2010) noted ethical traits come from a person’s inner self or blind spot. Leaders acting in an authentic fashion can have a positive outcome for both followers and stakeholders; internal and external (Day & Antonakis, 2011). Although, an ethical leader needs to be conscientious of the cost (blind spot) being more likely that the leader loses visionary focus and needs greater control. The blind spot trade-off offsets the “fair and just” (Day & Antonakis, 2011) situation garnered by ethical leaders. The group is most successful when closely aligned with leader’s traits and styles (Day & Antonakis, 2011). Traits and characteristics of leaders need to align with the group for there to be ethical leadership from the top down. Ethical leaders set expectations and lead by examples to allow others to see the honesty and integrity in their actions (Brown & Trevino, 2006). Leaders are most effective when authentic, are a moral manager and provide motivation.

The group thrives when leaders from the onset are ethical and find people and ways to build business relationships on trust and respect (Malos, 2012). Ethical leaders operating with the traits of honesty and integrity are easier to follow and have a business relationship. Conversely, the great man theory states, “great leaders are born and not made” (Malos, 2012). This is the opposite of the openness and respect associated with ethical leadership. The great man theory is militaristic in approach and does not progress to relational theories nor align with the advancement of women in the labour force. Females are perceived as more nurturing and communal, two traits deemed necessary in teambuilding (Eagly & Carli, 2003). This automatically creates a barrier for women being able to work authentically and effectively, when the great man theory is prevalent or think manager-think male prevails. Leaders need to have commitment to stand behind their decisions and have conviction (Friedman, 2011; Karp & Helgo, 2009). Leaders need to have situational awareness and be accountable for their role in the group and modify behaviours and decisions accordingly. The situations and reactions of leaders will inevitably define how successful or effective, a leader in an organization will be.

Leadership Styles

Meta-analysis conducted by Eagly & Karau in 1991, resulted in several findings that link prior research as well as providing academic justification for this research. Specifically, 75 experimental and field studies analyse the influence that gender had on leaderless groups and who would eventually become the leader. The meta-analysis examined research on men and women in originally leaderless groups or in evolving leadership situations. Results of the quantitative study revealed that males emerge as successful leaders more often than females, particularly in settings that were less social in nature and less established for short-term purposes (Eagly & Karau, 1991). Additional insights include that women were slightly more successful emerging into leadership roles where social interaction was essential. Eagly’s (1987) findings were corroborated and built upon, by the Eagly & Karau (1991) study and research by Eagly & Karau (2002) that studied role congruity theory. In essence, the research indicates that men emerge as leaders when task driven and agentic and women emerge as leaders when roles are more communal.

Androgynous

Eagly & Carli (2003) employed an empirical research study through observation and meta-analysis to authenticate their hypothesis that women have an advantage in effective leadership styles although the social labels and biases elude women from characteristically male dominated leadership positions. Eagly & Carli found their hypothesis strongly reinforced in younger leaders, newer companies and those that embrace a more androgynous leadership style. There is also discussion regarding how ineffective women in leadership can be due to prejudices that lean towards being more masculine and not because men are more adept leaders. Merely, there is statistically no difference. Therefore, perception and prejudice lead to the disparity in organizations. By having both sexes working toward middle, society leads both men and women into developing more androgynous leadership traits that potentially help balance perception and create awareness of female leaders in education and corporate environments (Way & Marques, 2013).

Leaders are now able to pull from both masculine and feminine characteristics based on contextual need and therefore are more effective across diverse situations. Emotions and communal attributes in the workplace are usually associated with being feminine and help foster perceptions that women are more transformational leaders. Research from a 2013 quantitative study yielded no difference in comfort level, trustworthiness or reliability with men and women (Way & Marques, 2013). Although, they stated leaders in general need to work at connecting (through emotions) to employees in a controlled manner, work still needs to be done to gauge how to communicate effectively in situations. There is a need for androgynous leaders embracing both perception of gender leadership qualities as the current workforce has seen a steady increase in women in management roles and the assumption would be that there would be less emphasis on masculine traits and move toward more androgynous roles to allow for both feminine and masculine qualities (Powell, Butterfield & Parent, 2002). Women experimenting with androgynous leadership styles do so to combat the perception that men are better bosses by both men (80%) and women (Singh, Nadim & Ezzedeen, 2012).

In their examination of rationales for gender segregation, Gherardi & Poggio (2001) indicated that gender is something we do every day and an inseparable part of who we are. Their qualitative study in Italy that looked more closely at how females move from a new comer to a more androgynous member of the work group (i.e., ambivalence) helped to show how gender is a second skin and how women transition to more androgynous members of the group. The transition occurs through three sets of rules that influence the perception and acceptance of women in male dominated roles or organization (e.g. necessary conditions, recipes and tactics). The results showed a double bind for women. Women can conduct oneself like a woman and accentuate the dissimilarities, which leads to conflict. Alternatively, women can conduct oneself like a man and try to fit the agentic leader model at the cost of distrust and censure for being inauthentic (Gherardi & Poggio, 2001; Ingols et al., 2015). Eagly & Karau (2002) discussed the double standard in that women were given the negative and unfavourable review for being inauthentic and that a male would have an easier time and being perceived to be the task-leader and having the competence, regardless of leadership ability due to agentic behaviour description. The gender difference in leadership styles is contradictory (Snaebjornsson & Edvardsson, 2013). Women have become more androgynous in leadership style while men have changed very little. Men and women lead companies in a similar manner and both women and men perceive a successful manager’s leadership style to be masculine (Snaebjornsson & Edvardsson, 2013). Women have taken on a more masculine and androgynous leadership style shows that women have the perception of historically stereotypical male leadership qualities to lead to success. Women continue to believe that successful leadership is to adopt masculine leadership style and there was no difference in gender on perceived managerial effectiveness (i.e., males and females were equally proficient in managerial work (Snaebjornsson & Edvardsson, 2013).

Collaborative

Corporations need to invest in their personnel if they are going to continue to retain sought after skills, abilities and talents (Kontoghiorghes & Frangou, 2009). Whether it is through additional training and education or confidence building by allowing employee autonomy or high threshold for risk, employers need to build up their employees. An employee needs to feel valued and respected (i.e., given positive feedback or reassurances) in order to feel secure enough to be a high performer that will not only have management behind them, but a safe haven to be open with suggestions or recommendations. Employees need to be a “respected partner” (Kontoghiorghes & Frangou, 2009) in order to be successful in the field of talent management. Preventing employees from speaking openly and honestly or excluding them from decision-making processes will cause them to take their talents elsewhere. People spend too much of their days at their place of employment to be in a negative feeling atmosphere and if the means to change that are presented, then an employee will take the positive over the negative.

Having a synergistic approach with the team and emphasizing that the success or failure, of the team is dependent on each person on the task. In order to have beneficial and worthwhile findings, individuals need to participate in a way that their actions parallel with their co-workers actions (Cole & Teboul, 2004). Detractors from teamwork and partnership can include variances in working style and having an overabundance of leaders and too little followers (Belcher). Leaders have to navigate through personality and work differences that cause struggle and discord on a task. Team members need to strive to work together in order to spur innovation and not let the conflicts be the detractor but the enabler to get the greatest results imaginable. Collaboration is founded in human interaction and the best form of human interaction is face-to-face (“Why personal interaction,” 2013). Collaboration allows individuals to locate resources and abilities to solve complications that may not be achievable by the individual alone. People and colleagues need to be able to build trust and work within a common culture to be able to innovate. People are able to come together in a virtual world and still work the face-to-face connection through video conferencing. This still allows a group to build trust and network accordingly to get the job accomplished.

Education

Women leaders need to teach men about gender, women and women in leadership positions (Llopis, 2013). Women getting higher education on safer workspaces for identity development and enacting true leadership change helps not to encourage the pejorative perception of women in leadership positions (Ibarra, Ely & Kolb, 2013; Paris & Decker, 2012). Formal MBA programs have continued to progress the double bind for women by enforcing gender norms (Kelan, 2013). The concept of becoming more gendered creates a double bind for women (Kelan, 2013). One example is educators displaying a problem with personal image and how image can affect leadership effectives (Kelan, 2013). One possible solution, instructors (in a school setting) or management (in a business setting) decisions should include a woman in business to help both men and women to learn what ideal leadership traits are, regardless of gender. Another example shows that there is still a pro-male bias in management students at the university level (Paris & Decker, 2012). Findings showed that students in the business administration program were more likely to gender stereotype and follow the think manager-think male paradigm than those not enrolled in the business administration program (Paris & Decker, 2012). Through education, formal and informal, women can control their own destiny and work to break down perceptions of women leadership positions and show they are great leaders regardless of gender (Ibarra et al., 2013). However, business administration programs should re-evaluate the approaches used to teach diversity in management education (Paris & Decker, 2012).

It is also hard to pinpoint what makes a leader great (Llopis, 2014). Therefore, to describe what characterizes a great female leader proves difficult and makes it even more challenging to advise which qualities and abilities lead to success in the business world (Llopis, 2014). However, women have an instinctual nature and handle on emotions that enables them to manage a crisis more communally and collaboratively and education is key to making this all unfold (Cole & Teboul, 2004; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Llopis, 2014).

Rationale for Gender-Specific Research of Women

Women consider them more interdependent or connected to others than do men (Reza, 2009). This is in part due to the development and maintenance of social relationships. These connections can lead to stereotypes that are not favourable to leadership and management positions, albeit authentic to oneself and following societal norms. With not being true to oneself or not following societal norms, women find that men stereotypically have difficulty following or have less loyalty for female leaders (Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt & van Engen, 2003). In contrast, males are to be acting themselves when striving to be more independent, individualistic and unique (Eagly & Karau, 2002). This places less emphasis on the aspects women state that they value and are in direct opposition to characteristics of male counterparts and leadership characteristics. The differences in self-construal result from the gender-based socialization that begins in early childhood (Reza, 2009).

Over the past 30-40 years, the American workforce has changed significantly with regard to gender. More women participate in the workforce than before: 43.3% of women worked in 1970 (Schein, 1973); women now represent almost half of the American workforce (Warner, 2014; Ways & Marques, 2013). The traditional family model, with the man working for pay and the woman working in the home, is no longer the only way, even if society still holds true to that men are the bread winner and women stay at home (Marche, 2013). It comes back to the decision of what is best for the family and how can the family unit sustains best (Marche, 2013).

Lopsided gender roles, especially in terms of the traditional family model, happen without realizing it. Society has engrained so deeply that the women are the caregiver, that when once home from the hospital, roles naturally develop. Women take on what is known as the second shift (Milkie, Raley & Bianchi, 2009; Ransdell, 2014). Women have made more progress in the workplace with parity than in the home (Milkie, Raley & Bianchi, 2009; Ransdell, 2014; Sandberg, 2013). Women will do more than 40 percent of the childcare efforts and 30 percent more household work than their partner (Milkie, Raley & Bianchi, 2009; Ransdell, 2014).

As the world changes and evolves, so do the people living it. Perceptions are not stagnant and leadership effectiveness can be affected due to societal changes. The consistent ebb and flow of evolution of the societal perceptions of women especially create more challenges in business as the archetypes for behaviours in business are incongruent to those that are strongly ingrained in society. Major themes reforming the business landscape, as well as the perception of women as managers and leaders, include more women world leaders, more women in the C-suite and more women graduating with masters degrees and above. In general, this is more exposure to women in leadership roles. In addition, there is more ambition with women in business today. Prior generations were stay at home mothers and not career driven. Businesses are starting to realize there is not one definition of an effective leader and to embrace the differences women bring to the corporate table.

Conclusion

Perception is a funny thing. “We don’t see things as they are; we see things as we are” (Vivyan, 2009). Based less on reality and more on assumptions, perceptions are what we have been told or learned to believe. Perceptions can hamper progress as stereotypes persist in the workplace. The existing literature displays strong evidence for gender stereotypes in several business settings and scenarios. Over 40 years of research has shown that although women have grown exponentially in the workforce (i.e., 51.5% of women holding management and professional titles, yet only occupy 14.4% of executive positions) (Heilman, 2012) and becoming a larger percentage of the breadwinners at 40% (Ingols et al., 2015), there is still a disparity in perceived leadership effectiveness. Managers and leaders still need to possess agentic characteristics to be successful; however, society has not caught up to allow social roles the flexibility to apply agentic behaviours to women. The pejorative double bind has created an environment deeply embedded of skeptics, of mistrust, of self-preservation and all at the expense of good leadership. The predecessors to think manager-think male were trait theory and behaviour theory, which specifies “intelligence and dominance” as being signs of great leaders (Day & Antonakis, 2011). Therefore, it is not a far jump to gender behaviours (i.e., roles) and how mimicking behaviours against type are seen as inauthentic and create the pejorative outcome we see today. Learning about behaviours and traits naturally leads to relationships and how those characteristics mix (Day & Antonakis, 2011). As theories continue to expand and bring in new or additional data, either a newer theory needs to evolve or a resurgence of the old will occur (Van Wart, 2013). More research needs to occur to understand society’s oppressing need for role congruence versus the ability for companies to utilize authentic, ethical or relationship theories. Companies can continue to thrive and allow contextual understanding and needs of leaders through additional training and possible use of co-creation theory (i.e., dissolution of the leader with personal dominance in favour of communal beliefs), versus the binding limitations of society on women by emphasizing corporate need and culture over societal perceptions (Ransdell, 2014).

References

- Adler, N.J. (2002). Global managers: No longer men alone. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(5), 743-760.

- Alewell, D. (2013). Be successful - Be male and masculine? On the influence of gender roles on objective career success. Evidence-Based HRM, 1(2), 147-168.

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. (2014). Women (and mothers) in the workforce: Worldwide factors. Women's Studies International Forum, 44(0), 164-171.

- Belcher, L.M. (n.d.). Advantages & disadvantages of collaboration in the workplace. Retrieved from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-disadvantages-collaboration-workplace-20965.html

- Begun, B. (2017). Give me a break. Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 62.

- Bezrukova, K., Thatcher, S.B., Jehn, K.A. & Spell, C.S. (2012). The effects of alignments: Examining group fault lines, organizational cultures and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 77-92.

- Brandt, T. & Laiho, M. (2013). Gender and personality in transformational leadership context. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34(1), 44-66.

- Broverman, I., Broverman, D., Clarkson, F., Rosenkrantz, P. & Vogel S. (1970). Sex role stereotypes and clinical judgments of mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 34(1), 1-7.

- Brown, M.E. & Treviño, L.K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595-616.

- Coder, L. & Spiller, M.S. (2013). Leadership education and gender roles: Think manager, think? Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 17(3), 21-51.

- Cole, T. & Teboul, J.C.B. (2004). Non-zero-sum collaboration, reciprocity and the preference for similarity: Developing an adaptive model of close relational function. Personal Relationships, 11(2), 135-160.

- Cullen, K.L., Palus, C.J., Chrobot-Mason, D. & Appaneal, C. (2012). Getting to “we”: Collective leadership development. Industrial & Organizational Psychology, 5(4), 428-432.

- Day, D.V. & Antonakis, J. (2011). The nature of leadership (Second Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- DeLaine-Hart, E. (2009). The experience of women aspiring to and holding executive leadership positions in the public sector: A generic qualitative study. Doctoral dissertation, Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

- Dickson, M.W., Den Hartog, D.N. & Mitchelson, J.K. (2003). Research on leadership in a cross-cultural context: Making progress and raising new questions. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 729-768.

- Drath, W. (2001). The deep blue sea: Rethinking the source of leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Duehr, E.E. & Bono, J.E. (2006). Men, women and managers: Are stereotypes finally changing? Personnel Psychology, 59(4), 815-846.

- Eagly, A.H. (1987). Sex differences in social behaviour: A social role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

- Eagly, A.H. & Carli, L.L. (2003). The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 807-834.

- Eagly, A.H. & Carli, L.L. (2007). Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 63-71.

- Eagly, A.H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C. & van Engen, M.L. (2003). Transformational, transactional and laissez-faire leadership styles; a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 569-591.

- Eagly, A.H. & Karau, S.J. (1991). Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(5), 685-710.

- Eagly, A.H. & Karau, S.J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573-598.

- Ely, R.J., Ibarra, H. & Kolb, D.M. (2011). Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women's leadership development programs. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(3), 474-493.

- Fiedler, F.E. (1971). Leadership. Morristown, NJ: General Learning.

- Forbes, M. (2014). PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi on why women can’t have it all: Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com

- Friedersdorf, C. (2014). Why PepsiCo CEO Indra K. Nooyi can’t have it all: The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com

- Friedman, K. (2011). You're on! How strong communication skills help leaders succeed. Business Strategy Series, 12(6), 308-314.

- Gherardi, S. & Poggio, B. (2001). Creating and recreating gender order in organizations. Journal of World Business, 36(3), 245-259.

- Hambrick, D.C. & Mason, P.A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193-206.

- Heilman, M.E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women's ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657-674.

- Heilman, M.E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 32, 113-135.

- Hewlett, S.A., Luce, C.B. & Servon, L.J. (2008). Stopping the exodus of women in science. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), 22-24.

- Hillary Clinton’s concession speech-full transcript. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/09/hillary-clinton-concession-speech-full-transcript/

- House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37(1), 3-10.

- Ibarra, H., Ely, R. & Kolb, D. (2013). Women rising: The unseen barriers: Cover story. Harvard Business Review, 91(9), 60-8.

- Ignatius, A. (2013). Now is our time. Harvard Business Review, 91(4), 84-88.

- Ingols, C., Shapiro, M., Tyson, J. & Rogova, I. (2015). Throwing like a girl: How traits for women business leaders are shifting in 2015. CGO Insights, 41(1), 1-6.

- Johns, M.L. (2013). Breaking the glass ceiling: Structural, cultural and organizational barriers preventing women from achieving senior and executive positions. Perspectives in Health Information Management/AHIMA, American Health Information Management Association.

- Karp, T. & Helgo, T.I.T. (2009). Leadership as identity construction: The act of leading people in organizations: A perspective from the complexity sciences. The Journal of Management Development, 28(10), 880-896.

- Katila, S. & Eriksson, P. (2013). He is a firm, strong-minded and empowering leader, but is she? Gendered positioning of female and male CEOs. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(1), 71-84.

- Kelan, E. (2013). The becoming of business bodies: Gender, appearance and leadership development. Management Learning, 44(1), 45-61.

- Koenig, A.M., Eagly, A.H., Mitchell, A.A. & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616-642.

- Kontoghiorghes, C. & Frangou, K. (2009). The association between talent retention, antecedent factors and consequent organizational performance. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 74(1), 29-36.

- Kotter, J. (2012). The key to changing organizational culture: Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkotter/2012/09/27/the-key-to-changing-organizational-culture/

- Kuppler, T. (2014). Culture and leadership: They’re simply two sides of the same coin. Retrieved from http://www.tlnt.com/2014/03/12/culture-and-leadership-theyre-simply-two-sides-of-the-same-coin/

- Kyriakidou, O. (2012). Gender, management and leadership. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 31(1), 4-9.

- Lester, D. (2013). Measuring Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Psychological Reports, 113(1), 15-17.

- Llopis, G. (2014). The most undervalued leadership traits of women: Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/glennllopis/2014/02/03/the-most-undervalued-leadership-traits-of-women/

- Malos, R. (2012). The most important leadership theories: Annals of Eftimie Murgu University Resita, Fascicle II. Economic Studies, 413-420.

- Marche, S. (2013). The masculine mystique. The Atlantic Monthly, 312(1), 114-126.

- McCallum, S. & O'Connell, D. (2009). Social capital and leadership development. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(2), 152-166.

- McGregor, J. (2017). Why this Wall Street powerhouse says women shouldn’t try to be like men at work: Washington post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/on-leadership/wp/2017/01/16/why-the-once-highest-ranking-woman-on-wall-street-says-women-shouldnt-try-to-be-like-men-at-work/?utm_term=0.4122f389c8c5

- Miles, R.E., Coleman,Henry J. & Creed, W.E.D. (1995). Keys to success in corporate redesign. California Management Review, 37(3), 128-145.

- Milkie, M.A., Raley, S.B. & Bianchi, S.M. (2009). Taking on the second shift: Time allocations and time pressures of U.S. parents with pre-schoolers. Social Forces, 88(2), 487-517.

- Oakley, J.G. (2000). Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 321-334.

- Orser, B. (1994). Sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics: An international perspective. Women in Management Review, 9(4), 11-19.

- Paris, L.D. & Decker, D.L. (2012). Sex role stereotypes: Does business education make a difference? Gender in Management, 27(1), 36-50.

- Powell, G.N., Butterfield, D. & Parent, J.D. (2002). Gender and managerial stereotypes: Have the times changed? Journal of Management, 28(2), 177-193.

- Ransdell, L.B. (2014). Women as leaders in kinesiology and beyond: Smashing through the glass obstacles. Quest, 66(2), 150–168.

- Reza, E.M. (2009). Identity constructs in human organizations. Business Renaissance Quarterly, 4(3), 77-107.

- Roberts, L.M., Dutton, J.E., Spreitzer, G.M., Heaphy, E.D. & Quinn, R.E. (2005). Composing the reflected best-self-portrait: Building pathways for becoming extraordinary in work organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 712-736.

- Sandberg, S. (2013). Lean in: Women, work and the will to lead. New York, NY: Random House.

- Scharmer, O. (2010). The blind spot of institutional leadership: How to create deep innovation by moving from ego system to ecosystem. Retrieved from http://www.ottoscharmer.com/docs/articles/2010_DeepInnovation_Tianjin.pdf

- Schein, E.H. (1978). Career dynamics: Matching individuals and organizational needs. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Schein, E.H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45(2), 109-119.

- Schein, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd Edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, V.E. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57(2), 95-100.

- Schein, V.E. (1975). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 340-344.

- Schein, V.E. (2007). Women in management: Reflections and projections. Women in Management Review, 22(1), 6.

- Schmitz, S., Rebelo, T., Gracia, F.J. & Tomá, I. (2014). Learning culture and knowledge management processes: To what extent are they effectively related? Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(3), 113-121.

- Schwartz, F.N. (1989). Management women and the new facts of life. Harvard Business Review, 67(1), 65-76.

- Silver, F. (n.d.). Challenges for employers when balancing work & family life. Retrieved from http://work.chron.com/challenges-employers-balancing-work-family-life-6045.html

- Singh, P., Nadim, A. & Ezzedeen, S.R. (2012). Leadership styles and gender: An extension. Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(4), 6-19.

- Snaebjornsson, I.M. & Edvardsson, I.R. (2013). Gender, nationality and leadership style: A literature review. International Journal of Business & Management, 8(1), 89-103.

- Southworth, E.M. (2014). Shedding gender stigmas: Work-life balance equity in the 21st century. Business Horizons, 57(1), 97-106.

- Still, L. (1994). Where to from here? Women in management: The cultural dilemma. Women in Management Review, 9(4), 3-10.

- Stomski, L. & Leisten, J. (2015). Leading into the next frontier. Benefits Quarterly, 31(3), 22-28.

- Tuckman, B.W. & Jensen, M.C. (2010). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group Facilitation, 10, 43-48.

- Van Wart, M. (2013). Lessons from leadership theory and the contemporary challenges of leaders. Public Administration Review, 73(4), 553-565.

- Vivyan, C. (2009). Different perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.get.gg/perspectives.htm

- Warner, J. (2014). The women’s leadership gap: Women’s leadership by the numbers. Centre for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/report/2014/03/07/85457/fact-sheet-the-womens-leadership-gap/

- Waters, V.L. (2004). Cultivate corporate culture and diversity. Nursing Management, 35(1), 36-50.

- Way, A.D. & Marques Joan (2013). Management of gender roles: Marketing the androgynous leadership style in the classroom and the general workplace. Organization Development Journal, 31(2), 82-94.

- Wiehl, L. (2007). The 51% minority. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Why personal interaction drives innovation and collaboration. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/skollworldforum/2013/04/09/why-personal-interaction-drives-innovation-and-collaboration/