Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 2

Validation of Customer Engagement Scale in Millennials in Digital Era

Satish Chandra Ojha, Harcourt Butler Technical University (HBTU), Kanpur

Teena Bharti, Indian Institute of Management Bodh Gaya

Reetu Singh, Harcourt Butler Technical University (HBTU), Kanpur

Urvashi Baronia, Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow

Citation Information: Chandra Ojha, S., Bharti, T., Singh, R., Baronia, U. (2024). Validation of customer engagement scale in millennials in digital era. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(2), 1-12.

Abstract

Purpose:-As businesses seek more efficient customer relations, researchers are working to identify the phenomenon of customer engagement using empirical methods. This study aims to explore the multidimensional nature of customer engagement by revisiting the psychometric properties of Vivek et al. (2014) scale. Design/methodology/approach:-This study used an online survey method to administer the responses and the data comprises of 445 millennials using online shopping services. We used factor and item analysis along with reliability and validity statistics by using SPSS 24.0 to confirm the factor structure of customer engagement. Findings:- The results revealed that a 3-factor model is an apt fit for assessing the customer engagement levels in millennials. Originality/value:- This research contributes to the customer engagement theory and demands to explore the negative engagement of customers which has been overlooked in the existing research.

Keywords

Customer Engagement, Consumers, Millennials, Social Media, Empirical Study.

Introduction

The term "customer engagement" (CE), albeit explored in academic literature from 2006, did not become well-known until 2010. As of yet, there isn't a consensus among the various schools of thought on how CE should be defined (Harrigan et al., 2017, Algharabat, 2020). Several well-known academics have provided the most thorough definitions of CE, including Vivek, et al. (2012), Hollebeek (2011a, 2016, 2022), Brodie et al. (2011), and Van Doorn et al. (2010). Although Hollebeek (2011a) and Brodie et al. (2011) defined CE in terms of consumers' psychological states, Van Doorn et al. (2010) focused on exploring CE from a behavioral angle. Vivek et al. (2012) examined CE from the perspective of “customers' involvement” and “connection with a brand's (firm's) activities or products”, which is a somewhat different perspective from the one taken by the previous study. Overall, CE is a notion that researchers may explore from many angles to achieve the identical goal, which is to influence desirable consumer behaviour (such as purchase intentions, positive brand sentiments, and loyalty).

Furthermore, the majority of CE research is done in the marketing sector, with a focus on key ideas like brand attachment, involvement, commitment, trust, loyalty, satisfaction, and value (Hollebeek, 2011b, Leckie et al., 2016, Nysveen and Pedersen, 2014, Vivek et al., 2012, Kumar and Nayak, 2019, Apenes Solem, 2016, Prentice et al., 2020, Thakur, 2016). In addition, relationship marketing has emerged and developed as a result of a number of factors, including the popularity of social media and the widespread adoption of new technologies (Quach et al., 2020; Barari et al., 2021). The use of smart devices and the availability of high-speed Internet have made it possible for customers to access brand-related information at their fingertips (Papakonstantinidis, 2017; Lamberton and Stephen, 2016). However, even though social media platforms are so easy to set up and use, customers nowadays can easily and vociferously exhibit their outlooks and thoughts toward various businesses through comments, likes, and shares on these websites (de Oliveira Santini et al., 2020; Buzeta et al., 2020). With CE poised to take centre stage in the online world, particularly on social media, such cases highlight the need for marketers to look for inventive ways to engage with customers. Although there is a substantial body of literature that aids in the understanding of the concept of customer engagement, millennials have not received much attention (Raghavan and Pai, 2021; Israfilzade and Babayev, 2020).

Thus, the focus of the study is essentially on millennials as they have emerged as the dominant consumer demographic in the digital age. The boom of e-commerce platforms with the advent of technology must effectively comprehend and meet the needs of millennials because of the distinctive traits and preferences that shape their expectations and interactions with online businesses (Willems et al., 2019). Having grown up during a time of rapid technological advancement, millennials are considered to be "digital natives." They are much more at comfortable conversing online and are used to the convenience and promptness that e-commerce offers (Raghavan and Pai, 2021). E-commerce companies must, therefore, offer seamless user experiences across various digital touchpoints, such as websites, mobile apps, and social media platforms, in order to engage millennials. Keeping this view in mind this study tries to analyse the psychometric properties of customer engagement scale in Indian millennials.

Literature Review

A synthesis of the various conceptual definitions of Customer Engagement (CE) that are currently available in the literature on marketing management is provided in Table 1. Further Vivek et al. (2014) discussed about the CE's conceptual framework in relation to the connection between marketing and service-dominant (S-D) logic. Additionally, Vivek et al. (2012) offered a precise definition of Customer Engagement (CE), which was based on their theory-building efforts and was derived from themes found in the qualitative analysis. CE is described as "the intensity of a person's connection and participation in an organization's offerings and/or organizational activities, which either the customer or the organization initiate." They then created a conceptualization of the construct that includes the three elements: conscious attention, enthusiastic participation, and social connection as detailed below. This three-dimensional construct has a lot of potential to analyse Customer Engagement's (CE) specifics.

| Table 1 Definitions of Customer Engagement (Adapted from Raghavan and PAI (2021) | ||

| Definition | Authors and year | Concept/term |

| “The consumer's natural desire to communicate or cooperate with other members of the community is boosted when they identify with the brand community”. | Algesheimer et al. (2009) | “Community engagement” |

| “An individual distinction representing customers' propensity includes major brands in their self-perception”. | Sprott et al. (2009) | “Brand Engagement in self – concept” |

| "Community engagement is a motivating experience that involves being connected to a certain medium”. | Calder et al. (2009) | “Community engagement” |

| “A state of being involved, occupied, fully absorbed, or engrossed in something that causes a certain attraction or repulsion force to be generated”. | Higgins and Scholer (2009) | “Engagement” |

| “A psychological process that simulates the underlying mechanisms by which new customers of a service brand develop loyalty, as well as the mechanisms by which repeat purchase customers of a service brand keep loyalty”. | Bowden (2009a) | “Consumer engagement” |

| “Cognitive effort, or the amount of cognitive capacity used on a specific task, is a component of the audience engagement”. | Scott and Craig-Lees (2010) | “Audience engagement” |

| “Modes of Engagement refer to the various approaches of persuasion”. | Philips and Macqruarirrie (2010) | “Engagement in Advertising” |

| “The extent of a consumer's cognitive, emotional, and behavioral investment in specific brand encounters is referred to as customer brand engagement”. | Hollebeek (2011b) | “Customer engagement behavior” |

| “In focal service relationships, a psychological condition that arises as a result of collaborative, co-creative client interactions with a focal agent” | Brodie et al (2011) | “Customer engagement” |

| “The degree to which an individual participates in . is connected to the organization's offerings and activities, whether initiated by the customer or the organization itself”. | Vivek et al. (2012) | “Consumer engagement” |

| “A psychological condition resulting from interactive, co-creative consumer interactions with a focal agent/object in focal service relationships.” | Brodie, Hollbeek, Juric & llic (2013) | “Consumer engagement” |

| “The physical, cognitive, and emotional "presence" of a consumer in their connection with a service business”. | Patterson et al. (2016) | “Consumer engagement” |

| “Customer engagement is the readiness of a customer to actively participate and interact with the focal object (e.g., brand/organization/community/website/organizational activity), [which] varies in direction (positive/negative) and magnitude (high/low) depending upon the nature of a customer’s interaction with various touch points (physical/virtual)”. | Islam & Rahman (2016) | “Customer engagement” |

Conscious Attention

According to marketing literature, conscious attention is "the level of interest the person has or wishes to have in interacting with the focus of their engagement." Notably, the terms "conscious attention" and "immersion and activation" of Hollebeek's (2011) and Calder et al., (2009) personal dimensions are interchangeable. According to psychological insights, the true level of an individual's involvement is frequently assessed in terms of conscious involvement, where neurophysiological and psychophysiological measurements offer ways to elicit emotional responses through the potency of the associations it sets off because the relative potency of associations resonates with the consumer (Weinberger, 2014).

Enthused Participation

Enthused participation is the term used to describe a person's behaviors and emotions when he or she engages in an activity. The effectiveness of customer engagement depends on this type of behavior (Vivek et al., 2014). Regardless of the exchange that is taking place, the emotional component of CE includes each individual's feelings (Paruthi & Kaur, 2017).

Social Connection

Vivek et al (2014) defined the concept of social connection as the “enhancement of the interaction based on the inclusion of others with the focus of engagement, indicating mutual or reciprocal action in the presence of others”. Further, Shaky et al. (2020) highlighted that 91% of consumers are aware of social media's ability to unite people despite their disparate backgrounds and beliefs, and 78% of them want brands to use digital media to engage with and foster relationships with their constituents. The importance of this idea has frequently been highlighted in the relevant literature and in theory (Calder et al., 2009; van Berlo et al., 2023). It strengthens the link between the consumer and the brand (Fournier, 2009). In this case, it should be noted that even though this relationship is two-way and appears to be reciprocal, it is the organization that essentially engages the customer and creates the society in which this social interaction occurs.

Further, Table 2 reflects the three-dimensional construct of customer engagement and few of the well-known researchers who have significantly contributed to this concept.

| Table 2 Customer Engagement Dimensional Structure | |

| Dimensions of CE (Vivek et al. 2014) | Related Dimensions in Literature |

| CA | “Absorption and Activation (Hollebeek, 2011b), Personal dimension (Calder et al., 2009) Cognitive dimension (e.g., Brodie et al., 2011; Algesheimer et al., 2005; Vivek et al.,2012; Hollebeek, 2011b; Dessart et al., 2015; Dovaliene et al., 2015), Cognitive stage (Kim et al., 2013)” |

| EP | “Hedonic experience (Gambetti et al., 2012; Calder et al., 2009) Emotional dimension (Brodie et al., 2011; Hollebeek, 2011a; Vivek et al., 2012) Affective stage (Kim et al., 2013)” |

| SC | “Social dimension (Vivek et al., 2012); Social behavior (Algesheimer et al., 2005; Abdul-Ghani et al., 2011), Social connection (Calder et al., 2009; Gambetti et al., 2012)” |

Methodology

Customer Engagement

We used an abridged version of customer engagement scale developed by Vivek et al. (2014). Its subscales of conscious attention, enthusiastic participation, and social connection have six, six and three items each. Examples include "I spend a lot of my free time ___," "I enjoy ____ more when I am with others," and "I am very interested in anything about __." The 7-point Likert Scale, which extended from 1 denoted by strongly disagree to 7 denoted by strongly agree, was utilized to collect responses to the scale items.

Procedure and Scoring

For the purpose of evaluating online responses from customers using online shopping services, a thorough and intensive survey was conducted. Data was gathered for 12 weeks, from August 10 to November 24, 2022. As the study dealt with multivariate data, the 510 completed questionnaires were examined for any missing information. The study excluded the questionnaires with missing data. The sample size was decreased to 445 following the procedure. The recommendations for structural equation modelling (SEM) made by Bagozzi and Yi (2012) were thus followed in this procedure. Male respondents made up only 39% of the sample, compared to 61% female respondents. The respondents were split into 5 age groups wherein 18–26 (27%); 27–31 (33%); 32–36 (19%); 37–41 (16%); and 42–50 (5%). Additionally, 12% of respondents had a higher secondary degree, 33% had a postgraduate degree, 50% had a graduate degree, and 5% had a PhD. In addition, the monthly income was split into 4 groups: the highest income earners (27%), the highest middle earners (36%), the lowest income earners (22%), and the lowest income earners (15%).

The coefficients of skewness and Kurtosis fell within the acceptable range of +/-1 standard deviation, which confirmed the data's normality (whether it is normally distributed). The procedure showed that the study's data variables were skewed (both positively and negatively), but because the outliers were within a reasonable range, the data's normality was not found to be significantly intimidated. To gauge the instruments’ internal consistency, Cronbach alpha (i.e., reliability coefficient) and composite reliability (CR) were identified even further. AVE (Average Variance Extracted), MSV (Maximum Shared Variance), and ASV (Average Shared Value) were used in the study, according to Hair et al. (2014), to analyze the validity. In order to check for non-multi-collinearity (where there is little or no correlation between the independent variables), the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values were computed (the values should remain below 10).

Demographic Information

The demographic information section includes the respondents' gender, age, level of education, and economic situation. A categorical grading scheme was used to compile the responses. A score of 1 was given to men, while a score of 2 was given to women. On a 5-point scale, 1 represented age 18 to 26, 2 represented age 27 to 31, 3 represented age 32 to 36, 4 represented age 37 to 41, and 5 represented age 42 to 50. On a 3-point scale, 1 represented higher secondary education, 2 graduate education, 3 postgraduate education, and 4 PhD education. Additionally, an income scale of 1 to 4 was used to measure income, with 1 representing low income, 2 lower middle income, 3 higher middle income, and 4 representing higher income.

Data Analysis Approach

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA, respectively) were carried out to determine the factor structure and the applicability of the discovered pattern to the relevant sample.

Validation of Customer Engagement Scale in Indian subcontinent

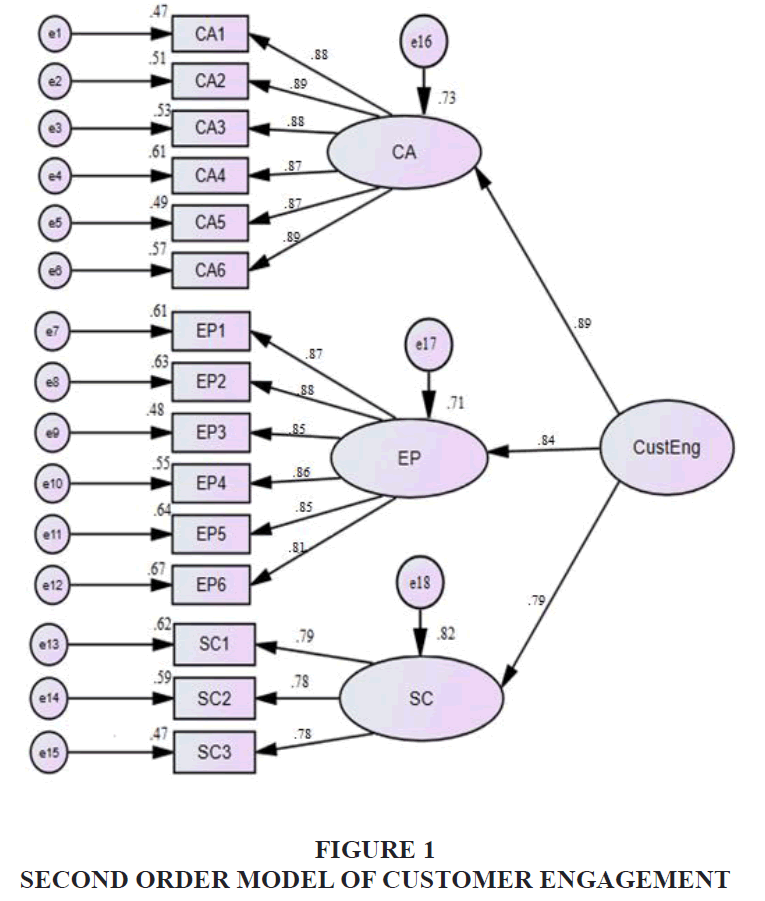

According to the study, a three-factor model best fits the construct of customer engagement (Table 3). The entire customer engagement scale was altered, and each construct was preserved at an Eigenvalue of more than 1.0. Customer engagement is made up of three sub constructs: conscious attention, enthusiastic participation, and social connection. The loadings in this case were all higher than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017).

| Table 3 Factorial Structure of Customer Engagement Scale | |||||||

| Construct | Items | Factor Loadings | t-values (p<.001) | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV |

| Conscious attention | CA_1 | .885 | 21.271 | 0.893 | 0.797 | 0.369 | 0.107 |

| CA_2 | .891 | 19.435 | |||||

| CA_3 | .885 | 18.710 | |||||

| CA_4 | .879 | 18.953 | |||||

| CA_5 | .873 | 17.253 | |||||

| CA_6 | .891 | 16.455 | |||||

| Enthused Participation | EP_1 | .871 | 16.242 | 0.845 | 0.773 | 0.363 | 0.155 |

| EP_2 | .886 | 16.164 | |||||

| EP_3 | .857 | 15.735 | |||||

| EP_4 | .867 | 15.163 | |||||

| EP_5 | .851 | 14.721 | |||||

| EP_6 | .815 | 13.931 | |||||

| Social Connection | SC_1 | .791 | 13.135 | 0.792 | 0.553 | 0.193 | 0.077 |

| SC_2 | .785 | 12.715 | |||||

| SC_3 | .787 | 11.651 | |||||

In order to assess the instrument's dependability, the study used Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α). For the factors influencing customer engagement, the coefficients of reliability were 0.893 for conscious attention (6 items), 0.845 for enthused participation (6 items), and 0.792 for social connection (3 items). Table 3 reflects the results of factor analysis. Additionally, the original scale had multiple dimensions, and the factor analysis also revealed that the Indian context had three sub-dimensions (Table 3). Contrary to other studies, which accepted a value closer to 0.1 as establishing instrument reliability, the results showed that the values were above the nominal range of Cronbach's alpha, or.60 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Nunnally, 1994). The tool's consistency was demonstrated by the overall reliability coefficient of the scale, which was 0.835.

By examining the scale's convergent and discriminant validity, the construct validity of the scale was evaluated. The sub-factors reported AVE > 0.5 in the case of convergent validity, which is favorable. Additionally, the Maximum Shared Value, Average Variance Extracted and Average Shared Value were computed and are shown in Table 3, wherein MSV and ASV values, as in theory, should always be less than AVE. According to Hair et al. (2012a), convergent validity is indicated by the value of composite reliability (CR) being greater than the value of average variance extracted (AVE). Moreover, an item-wise analysis was conducted to highlight that show that the reliability of the modified version of customer engagement scale is not improved by excluding any one item (Table 4).

| Table 4 Item Wise Analysis | ||||

| Scale Items | Scale mean (Item deleted) | Scale variance (Item deleted) | Corrected item total correlation | Cronbach’s α (Item deleted) |

| CA_1 | 62.39 | 57.77 | .687 | .830 |

| CA_2 | 62.58 | 57.11 | .632 | .809 |

| CA_3 | 60.31 | 56.39 | .678 | .815 |

| CA_4 | 61.76 | 56.47 | .651 | .811 |

| CA_5 | 60.87 | 56.85 | .657 | .852 |

| CA_6 | 61.47 | 57.29 | .677 | .875 |

| EP_1 | 62.33 | 56.77 | .687 | .899 |

| EP_2 | 62.98 | 56.11 | .631 | .897 |

| EP_3 | 60.11 | 56.39 | .679 | .889 |

| EP_4 | 61.56 | 55.47 | .645 | .879 |

| EP_5 | 59.97 | 56.85 | .657 | .801 |

| EP_6 | 62.16 | 58.28 | .715 | .830 |

| SC_1 | 62.06 | 58.35 | .677 | .811 |

| SC_2 | 62.84 | 58.61 | .659 | .873 |

| SC_3 | 62.91 | 57.33 | .617 | .890 |

In addition, the factor structure of customer engagement was ascertained using CFA. The maximum likelihood method was used to evaluate the three-factor (H3), two-factor (H2), and one-factor (H1) theoretical models by implementing CFA with SPSS AMOS 24. The findings revealed that H3a model, a 2nd order three factor model, had a good fit. Referring to the Table 5, the results presented that H3b (three-factor model) establishes a good fit indices χ²/df = 1.459, NFI = 0.937, GFI= 0.971, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.987, and RMSEA = 0.047, while H1 with one-factor of customer engagement i.e. conscious attention reported χ²/df = 4.311, NFI = 0.873, GFI=0.789, CFI = 0.875, TLI = 0.915, and RMSEA = 0.169 and H2 with 2-factor of customer engagement i.e. conscious attention and enthused participation χ²/df = 2.119, NFI = 0.863, GFI=0.813, CFI = 0.843, TLI = 0.895, and RMSEA = 0.097. Consequently, H2 and H1 reported a poor fit, while H3 (Three factor model) has an overall good model fit. Further, it was emphasized by Carmines and Mclver (1983) that a value for χ²/df (normed chi square) of less than 3.00 was regarded as acceptable for a model fit. In addition, Hu and Bentler (1999) defined that the cutoff value for the GFI above 0.90 as well as the threshold value for the NFI, CFI, and TLI as positive values. Figure 1 also depicts the 2nd order model of client interaction that was applied in this research.

| Table 5 CFA Results for Customer Engagement Scale | |||||||

| S. No. | Details | χ2/ df | GFI | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

| 1 | 3-factor Model (H3a) | 1.478 | 0.971 | 0.937 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.047 |

| 2 | 3-factor Model (H3b) | 1.731 | 0.717 | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.907 | 0.041 |

| 3 | 2-factor Model (H2) | 2.119 | 0.813 | 0.863 | 0.895 | 0.843 | 0.095 |

| 4 | 1- factor model (H1) | 4.311 | 0.789 | 0.873 | 0.915 | 0.875 | 0.169 |

Discussion

The results of the current study highlight the usefulness and wide applicability of the construct in Indian setting, where studies on customer engagement are receiving more attention globally. Both internally and externally, the advantages of a particular type of customer engagement behaviour must be utilised. For internal leveraging, the right individuals inside the company must have access to the content of pertinent CEBs, such as suggestions, so they can use it appropriately, such as to come up with new product ideas (Nambisan and Baron, 2007). Also, businesses should encourage processes and environments that will stimulate CEB in order to nurture and maximize its positive potential (Thompson, 2005).

Researchers have confirmed that capturing the right sentiments of the customers, whether positive or negative, can help in getting complete assessment of the customers and in turn help the firms to engage with the customers by fostering the right customer engagement manifestations. Given this, it is crucial to have a tool that is reliable and valid from a scientific standpoint to measure customer engagement in the Indian context.

The objective of the current study was to assess the psychometric features of customer engagement in the millennials in digital era. The findings revealed that a 3-factor model is an apt fit for assessing the customer engagement levels in millennials.

The results of validity, CFA, and EFA analysis demonstrate that the conceptual structure of CE is consistent across cultures and nations. One of the explanations for the discovery of a similar factor structure of CE in the Indian millennials could be attributed to the original researchers' (Vivek et al., 2014) rigorous process of instrument development.

Practical Implications

It is evident that there can be no denying the significance of measuring customer engagement. In order to improve the customer satisfaction in association with a particular product or brand, marketing managers, professionals, practitioners, and behavior scientists should recognize the significance of engagement. As a result, organizations should invest in understanding and assessing customer engagement for better customer management. Also, based on customers' propensity to engage and the kinds of engagement behaviors they exhibit, CEB (customer engagement behaviour) can also be a useful framework for classifying and segmenting customers. A variety of pertinent CEBs could be added to the literature on customer segmentation, which tends to focus primarily on the customer's choice of the focal brand. Referrals, for example, may be even more significant than repeat purchasing in the case of services like health care. We think that marketers will be more effective at engaging their markets if they have a greater understanding of how to do so. Understanding CE dimensionality is therefore useful in that context. To put it another way, how much of a customer's engagement is driven by interest or a desire to learn more about the brand or entity versus how much of the customer's effort is spent on merely using or being absorbed in the use of the product, brand, or experience. Also, businesses can gauge the success of their initiatives by monitoring and analyzing customer engagement metrics. This makes it possible to continuously optimize because it gives a clear picture of what is working and what needs improvement. By using insights from customer interactions and experiences, businesses can adapt their strategies, enhance customer experiences, and ultimately foster growth, loyalty, and success in today's competitive marketplace (Balio and Casais, 2021).

Furthermore, since social media presents excellent opportunities for marketers to increase their market share and engage with their customers while also enabling customers to communicate with one another or the business, the research's findings will aid marketers in strategically positioning the advertising for their products and services. As evidenced by the page's consistent updates and upkeep on social media platforms, businesses should strive to consistently update their online existence and communication in order to link with both potential and active customers.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study has some limitations as discussed below. Even though the CE scale seems reliable, more research is necessary. While positive WOM, blogging, and recommendations may initially result from engagement, they can also cause a feedback loop through subsequent influence on CE, which merits investigation with longitudinal studies rather than our static study (Malthouse and Calder 2011, Vivek et al., 2014). Further, the scale only acknowledges the positive side of the customer engagement whereas CE can be both positive and negative. Hence, the future researchers can explore the negative customer engagement. This scale could be modified to relate to engagement across or in different venues, as was previously mentioned, to make it even more helpful. This extension is a crucial area for future research given the significance of online communities. Therefore, future studies can perform longitudinal as well as cross-cultural/cross-generation analysis of customer engagement to further assess the level of customer engagement. Also, further research is necessary to fully comprehend the motivations connected to various brand pages as it is still a mystery to be decoded wherein its unclear whether people prefer what they like or what other people like (Farook and Abeysekara, 2016).

Furthermore, this study considers the millennials in a digitally transforming economy with access to widely and freely available information. Thus, future studies can explore the millennials- Gen Z and Alpha i.e., digitally savvy generation experiencing pandemic, various emotions, and other severe climatic changes Appendix Table 1.

| Appendix Table 1 Online Shopping | |

| Construct | Items |

| Conscious attention | I like to know more about _____. |

| I like events that are related to _____. | |

| I like to learn more about _____. | |

| I pay a lot of attention to anything about __. | |

| I keep up with things related to ______. | |

| Anything related to ___ grabs my attention. | |

| Enthused Participation | I spend a lot of my discretionary time ____. |

| I am heavily into ______. | |

| I try to fit ______ into my schedule. | |

| I am passionate about _____. | |

| My days would not be the same without ___. | |

| I enjoy spending time ___. | |

| Social Connection | I love ____ with my friends. |

| I enjoy ____ more when I am with others. | |

| _____ is more fun when other people around me do it too. | |

References

Abdul-Ghani, E., Hyde, K. F., & Marshall, R. (2011). Emic and etic interpretations of engagement with a consumer-to-consumer online auction site. Journal of business research, 64(10), 1060-1066.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of marketing, 69(3), 19-34.2

Algharabat, R., Rana, N. P., Alalwan, A. A., Baabdullah, A., & Gupta, A. (2020). Investigating the antecedents of customer brand engagement and consumer-based brand equity in social media. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101767.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Apenes Solem, B. A. (2016). Influences of customer participation and customer brand engagement on brand loyalty. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(5), 332-342.

Balio, S., & Casais, B. (2021). A content marketing framework to analyze customer engagement on social media. In Research Anthology on Strategies for Using social media as a Service and Tool in Business (pp. 320-336). IGI Global.

Barari, M., Ross, M., Thaichon, S., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2021). A meta-analysis of customer engagement behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 457-477.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bowden, J. L. H. (2009). The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of marketing theory and practice, 17(1), 63-74.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Juric, B., & Ilic, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of service research, 14(3), 252-271.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of business research, 66(1), 105-114.

Buzeta, C., De Pelsmacker, P., & Dens, N. (2020). Motivations to use different social media types and their impact on consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). Journal of Interactive Marketing, 52(1), 79-98.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Calder, B. J., Malthouse, E. C., & Schaedel, U. (2009). An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. Journal of interactive marketing, 23(4), 321-331.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carmines, E.G., & McIver, J.P. (1983). An introduction to the analysis of models with unobserved variables. Political methodology, 51-102.

de Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Pinto, D. C., Herter, M. M., Sampaio, C. H., & Babin, B. J. (2020). Customer engagement in social media: a framework and meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48, 1211-1228.

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: a social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1), 28-42.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dovaliene, A., Masiulyte, A., & Piligrimiene, Z. (2015). The relations between customer engagement, perceived value and satisfaction: the case of mobile applications. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213, 659-664.

Farook, F. S., & Abeysekara, N. (2016). Influence of social media marketing on customer engagement. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 5(12), 115-125.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

Fournier, S., & Lee, L. (2009). Getting brand communities right. Harvard business review, 87(4), 105-111.

Hair Jr, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107-123.

Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012a). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harrigan, P., Evers, U., Miles, M., & Daly, T. (2017). Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tourism management, 59, 597-609.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Higgins, E. T., & Scholer, A. A. (2009). Engaging the consumer: The science and art of the value creation process. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(2), 100-114.

Hollebeek, L. (2011). Exploring customer brand engagement: definition and themes. Journal of strategic Marketing, 19(7), 555-573.

Hollebeek, L. D., Conduit, J., & Brodie, R. J. (2016). Strategic drivers, anticipated and unanticipated outcomes of customer engagement. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 393-398.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hollebeek, L. D., Sharma, T. G., Pandey, R., Sanyal, P., & Clark, M. K. (2022). Fifteen years of customer engagement research: a bibliometric and network analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(2), 293-309.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Islam, J. U., & Rahman, Z. (2016). The transpiring journey of customer engagement research in marketing: A systematic review of the past decade. Management Decision, 54(8), 2008-2034.

Israfilzade, K., & Babayev, N. (2020). Millennial versus non-millennial users: context of customer engagement levels on instagram stories (extended version). Journal of Life Economics, 7(2), 135-150.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kim, D., & Perdue, R. R. (2013). The effects of cognitive, affective, and sensory attributes on hotel choice. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 246-257.

Kumar, J., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Brand engagement without brand ownership: a case of non-brand owner community members. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(2), 216-230.

Lamberton, C., & Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. Journal of marketing, 80(6), 146-172.

Leckie, C., Nyadzayo, M. W., & Johnson, L. W. (2016). Antecedents of consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5-6), 558-578.

Malthouse, E. C., & Calder, B. J. (2011). Comment: engagement and experiences: comment on Brodie, Hollenbeek, Juric, and Ilic (2011). Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 277-279.

Marino, V., & Lo Presti, L. (2018). Engagement, satisfaction and customer behavior-based CRM performance: An empirical study of mobile instant messaging. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 28(5), 682-707.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Interactions in virtual customer environments: Implications for product support and customer relationship management. Journal of interactive marketing, 21(2), 42-62.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Bernstein. Ih (1994). Psychometric theory, 3.

Nysveen, H., & Pedersen, P. E. (2014). Influences of cocreation on brand experience. International Journal of Market Research, 56(6), 807-832.

Papakonstantinidis, S. (2017). The use of social media in reducing professional uncertainty: an exploratory study. Nowadays and Future Jobs, 1, 6-13.

Paruthi, M., & Kaur, H. (2017). Scale development and validation for measuring online engagement. Journal of Internet Commerce, 16(2), 127-147.

Prentice, C., & Nguyen, M. (2020). Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 56, 102186.

Quach, S., Shao, W., Ross, M., & Thaichon, P. (2020). Customer engagement and co-created value in social media. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(6), 730-744.

Raghavan, S., & Pai, R. (2021). Changing Paradigm of Consumer Experience Through Martech–A Case Study on Indian Online Retail Industry. International Journal of Case Studies in Business, IT and Education (IJCSBE), 5(1), 186-199.

Scott, J., & Craig-Lees, M. (2010). Audience engagement and its effects on product placement recognition. Journal of Promotion Management, 16(1-2), 39-58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sprott, D., Czellar, S., & Spangenberg, E. (2009). The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Marketing research, 46(1), 92-104.

Thakur, R. (2016). Understanding customer engagement and loyalty: a case of mobile devices for shopping. Journal of Retailing and consumer Services, 32, 151-163.

Thompson, B. (2005). The loyalty connection: Secrets to customer retention and increased profits. RightNow Technologies & CRMguru, 18.

van Berlo, Z. M., van Reijmersdal, E. A., & van Noort, G. (2023). Experiencing branded apps: Direct and indirect effects of engagement experiences on continued branded app use. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 23(1), 73-83.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of service research, 13(3), 253-266.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. Journal of marketing management, 27(7-8), 785-807.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. Journal of marketing theory and practice, 20(2), 122-146.

Weinberger, C. J. (2014). The increasing complementarity between cognitive and social skills. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(5), 849-861.

Willems, K., Brengman, M. and Van Kerrebroeck, H. (2019). The impact of representation media on customer engagement in tourism marketing among millennials. European Journal of Marketing, 53(9), pp.1988-2017.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 14-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13901; Editor assigned: 16-Aug-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13901(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Sep-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13901; Revised: 26-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13901(R); Published: 12-Jan-2024