Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 4S

Unravelling Mindful Work Engagement in the Digital Generation: The Interplay of Social Media Usage

Puja Agarwal, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Paramjit S Lamba, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Neera Jain, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Citation Information: Agarwal, P., Lamba, P.S., & Jain, N. (2025). Unravelling mindful work engagement in the digital generation: the interplay of social media usage. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S2), 1-22.

Abstract

Introduction

Generation Z (Gen Z) comprising of those born between 1996 and 2012, has always lived in a world where individuals can connect with others digitally with others instantly. Therefore, they prefer socializing online rather than physically, which has begun affecting society (Schwieger & Ladwig, 2018). Many identify themselves as digital device addicts (Beal, 2016), especially as they have received unparalleled exposure to technology since their childhood and use it to access news, academics, social networking, gaming, audio-video sharing, and reviews. Gen Z members are known as ‘digital natives’ (Helsper & Eynon, 2010). This generation’s interactions on social media comprise a significant portion of their socializing. Since they flit between different online sites, consuming information from multiple sources, their attention spans decrease continually, making it difficult to focus on one task for too long. Engaging in various tasks simultaneously can make it challenging to maintain concentration, leading to poor performance at work (Skaugset et al., 2016).

The notion that practicing mindfulness makes work more “enjoyable” has gained recognition by educational psychologists over time (Langer & Ngnoumen, 2020). Researchers have also established a positive relationship between mindfulness strategies and achievement (Hyland, 2015). Studies have proven that introducing mindfulness resulted in surprising positive outcomes such as enhanced concentration and focus, decreased levels of anxiety, and eagerness to teach (Burnett, 2011).Bunjak et al. (2022) showed that the most engaging situation while handling work requires the individual to be high in mindfulness. Ginasekara & Zheng (2018) state that mindfulness influences work engagement positively.

However, there is a paucity of research on the impact of individual constructs of mindfulness on the individual dimensions of work engagement. In addition, there is scant research on the influence of social media on the relationship between mindfulness and task engagement. This study aims to contribute to the underdeveloped scholarly exploration in this area through Study 1 and Study 2. This study answers the call given by Stuart-Edwards et al. (2023) by addressing how mindfulness can be leveraged for enhancing employee engagement and the mindful consumption of social media.

Mindfulness

Lau et al. (2006) have conceptualized mindfulness as a state practiced through meditation. However, Baer et al. (2006) view it as a trait or a person’s disposition to be mindful. Brown and Ryan (2003) posit that trait mindfulness tends to be consistent over a period of time. Increasing mindfulness through such interventions improves psychological health (Shahar et al., 2010). Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) have been shown to increase both state and trait-based mindfulness (Beaulieu, 2022). High levels of mindfulness are associated with higher levels of self-efficacy (Klainin-Yobas et al., 2016). Self-efficacy in turn has been associated with young persons' emotional and social adjustment (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2013). Duggan et al. (2024) posit that stress reduction techniques that enhance acceptance, enable stress reduction. Junca-Silva et al. (2023) posit that mindfulness may lead to more positive social behaviors and less negative ones.

Mindfulness has been conceptualized as consisting of two elements. The first component is awareness of current experiences. Kabat-Zinn (2005) refers to awareness as intentional attention paid in the present moment, without judgment. The second component is acceptance of the present moment without any preconceived notions of how it should or should not be (Bishop et al., 2004). Having a high level of acceptance has been associated with an enhanced ability to recover from negative emotional states (Keng et al., 2016).

This study examines the development of mindfulness in organizations through MBIs using online and offline courses, meditation exercises, installing transcendental music inside places like cafeterias at workplaces, and leveraging influencers to create a positive impact on the work engagement of Gen Z.

Work Engagement

Work engagement may be defined as a positive and fulfilling work-related state of mind characterized by dedication, absorption, and vigor (Storm et al., 2014). Dedication is a person's involvement in their work, and their experiencing enthusiasm, pride, and a sense of significance. Vigor is the level of energy and mental resilience while working on a task and persisting in the face of challenges. Absorption is the pleasant state of mind when an individual becomes immersed in their work and finds it difficult to disengage from it. Dedication, vigor, and absorption together form work engagement.

Employees who are engaged are often physically and psychologically healthy (Bakker, 2011). Since engagement is related to motivation and high performance, focusing on this will reap multiple benefits for organizations. Engaged employees play a key role in the success of organizations (Hoole & Bonnema, 2015), as they tend to complete all assigned work (Schaufeli et al., 2008). Due to their low attention span, Gen Z employees change jobs within short tenures, continually looking for new and exciting things to engage with (Ozcelik, 2015). A sharper focus on generating work engagement will benefit organizations by retaining digitally savvy, fast-acting, and self-reliant human resources, which would enhance the organization's productivity.

Social Media Usage and Gen Z

Tankovska (2021) posited that 95% of Gen Z members use social media as the primary way to interact socially. Due to excessive exposure to social media, this generation has become susceptible to anxiety and other psychological issues (Wheatley & Buglass, 2019). These concerns may impact the Gen Z member’s engagement with work.

Social media usage (SMU) is classified by researchers into two classes, based on the objective of use (Hsu et al. 2015). One objective is to initiate and maintain interpersonal relationships, and the other is to gather information. When social media is used for collecting information, users focus on the utilitarian value, which involves their cognition (Hu et al., 2017). In comparison, when social media is used for socializing, users are motivated by the hedonic value, which involves their emotions (Wang, 2010). In this study, SMU refers to both categories of usage.

For Gen Z, the influencers on social media are their role models (Mann et al., 2022). These influencers or ‘opinion leaders’ receive information from mass media and then pass on this information in a curated form to their audiences. Since individual social media users cannot have access to all the varied sources of information, they rely on opinion leaders as their main source. These opinion leaders or influencers share information with individuals having similar interests (Hong et al., 2015). By sharing their opinions on events, issues, products, or services, influencers exert influence on their followers and play a key part in communication (Nisbert & Kotcher, 2009). Gen Z prefers to believe in the assessment of these online influencers rather than advertisements by organizations (Jiang, 2009).

Current Study

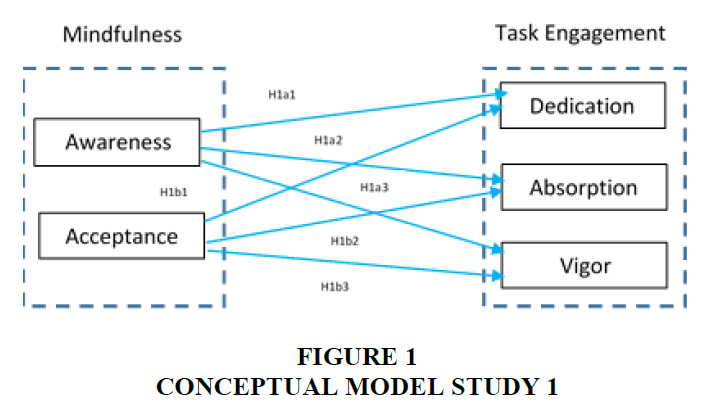

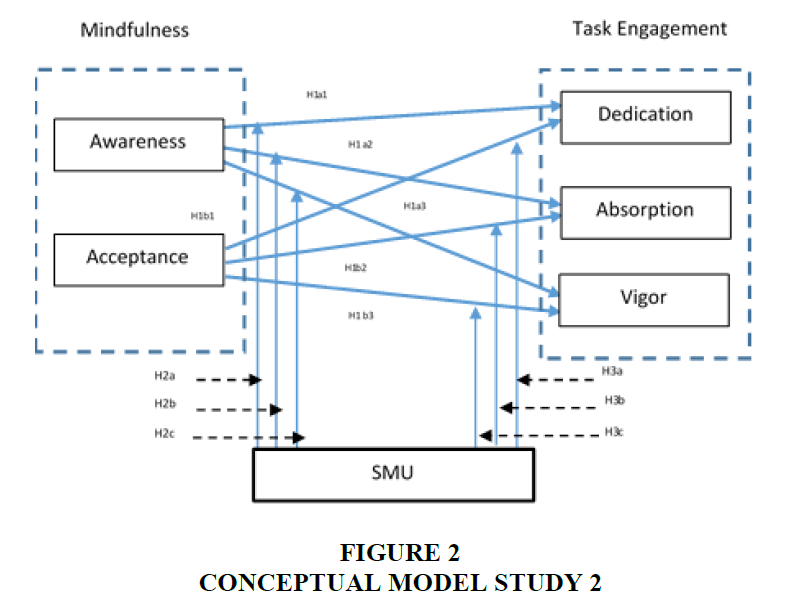

Gen Z has been born into a world where individuals connect with each other instantly, using digital means. Due to their propensity to shift quickly between sites, and consuming multi-sourced information, their attention spans have decreased continually, making it difficult to focus on one task for too long. Being engaged in multiple tasks simultaneously can, therefore, make it challenging to maintain concentration. Study 1 examines the relationship between the individual constructs of mindfulness (awareness and acceptance) with the individual elements of work engagement (dedication, absorption, and vigor). Study 2 explores the influence of social media usage (SMU) on each of these relationships. The two studies tested the following hypothesis. First, awareness has a significant impact on dedication, absorption, and vigor (Hypothesis 1a1, 1a2, 1a3; Study 1). Second, acceptance has a significant impact on dedication, absorption, and vigor (Hypothesis 1b1, 1b2, 1b3; Study 1). Third, SMU moderates the relationship between awareness and dedication, absorption, and vigor (Hypothesis H2a, H2b, H2c; Study 2). Fourth, SMU moderates the relationship between acceptance and dedication, absorption, and vigor (Hypothesis H3a, H3b, H3c; Study 2). The methodologies of both studies elaborate on the participants, procedure and measures used for the study. This is followed by analyses of the collected data, the results and discussion, separately for each study. The paper concludes with relevant takeaways for researchers andpractitioners.

Study 1

The conceptual model for this study is given below (see Figure 1).

Method

The context of this study is one of the largest developing economies in the world, India. We operationalized the study in India as it is home to one of the largest populations of young people in the world, with more than 20% of the world’s young population present here (Indbiz.gov.in, 2021). More than 40% of India’s population is under 25, with a median age of 28 years. In comparison, the median age for the United States is 38 years and in China, it is 39 years (Silver et al., 2023). Such characteristics imply a large composition of Gen Z in the country’s population.

Participants and Procedure

The questionnaire was sent to 510 respondents across northern India, using a purposive sampling technique. A total of 446 respondents submitted their responses to the questionnaires, and they did not have the issue of missing data.

After removing 6 casual responses using standard deviation values, the final sample (See Table 1) consisted of 121 females (27.5% of the sample population) and 319 males (72.5% of the population).

| Table 1 Demographic Details – Study 1 | ||

| Gender | ||

| Frequency | Frequency % | |

| Female | 121 | 27.5 |

| Male | 319 | 72.5 |

| Work Experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 118 | 26.8 |

| 1 to 2 years | 127 | 28.9 |

| More than 2 years | 195 | 44.3 |

| Education Level | ||

| Graduate-Academic (BA, BSc., Bcom., etc.) | 55 | 12.5 |

| Graduate-Professional (BE, BTech, MBBS, etc.) | 177 | 40.2 |

| Post-Graduate | 208 | 47.3 |

Material

Data were collected by adapting items from two questionnaires - the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS), and the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9).

Mindfulness

The PHLMS measures have been extensively used by many reputed publications in prior studies (Morgan et al., 2019). In this scale, the construct of awareness consisted of 10 items and the construct of acceptance also comprised 10 items (Cardaciotto et al., 2008, pg. 210). The respondents use a 1-5 Likert-type scale ranging from “never” to “very often” for each of the two subscales, awareness and acceptance.

Work Engagement

The UWES-9 scale was adapted from Schaufeli & Bakker (2010). The UWES-9 scale has been validated in studies across several nations, including Spain (Schaufeli et al., 2002), Greece (Xanthopoulou et al., 2012), and Japan (Shimazu et al., 2008). In this scale, the dedication, absorption, and vigor comprised 3 items each (Mills et al., 2012, pg. 527).

Procedure

The items were reviewed by the co-researcher to ensure accuracy and thereafter the questionnaire was converted into a Google form. The link to this form was shortened using bit.ly and this shortened link was sent to the respondents via WhatsApp and email. On average, it took 25 to 30 minutes to complete the questionnaire. At the beginning of the questionnaire, a section informed the respondents about the confidentiality and anonymity of their identities. After completing the section on informed consent and demographic particulars, the respondents proceeded to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire enabled the respondents to go back to their previous responses and change them if required.

Analysis

The data was prepared for the final analysis. 6 responses reflected a casual approach which was detected by conducting a standard deviation assessment and therefore dropped. Histograms and P–P plots were computed for the variables revealing a normal data distribution. A valid 440 responses were finally used for building the structural equation model. The data was analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 software package.

Results

As part of survey design remedies, this study ensured that the scales were valid, reputed, and well adapted by earlier published literature. The scale items were compact, simple, and easy to understand. The face and content validity of the measures was ensured by a review conducted by two subject matter experts. Participation in the survey was voluntary; and no compensation was paid to any participants.As a statistical remedy, we conducted the Harman single-factor test and found the variance extracted by the single factor was 43%, which is well within the threshold of 50% (Hair et al., 2019).

Common Method Variance (CMV)

CMV is commonly observed when self-reporting of the two variables under the structural relation is performed (Podsakoff, 1986). Chang et al. (2020) suggested the survey design administering remedies and statistical remedies. CMV is a higher concern where performance is a dependent variable, whereas in our study, dedication, vigor, and absorption were the dependent variables. Our instrument design arguments and statistical remedies confirmed that the study is free of CMV concerns. The study is free of multi-collinearity concerns because the inner variance inflation factors (VIF) of the key constructs were below 3 (see Table 2), while the threshold is 5 (Hair et al, 2019).

| Table 2 Measurement Model | ||||

| Loadings | Mean | SD | VIF | |

| M_Awareness | ||||

| Emotions | 0.782 | 3.750 | 0.909 | 1.366 |

| Conscious | 0.790 | 3.700 | 0.820 | 1.522 |

| Experience | 0.831 | 3.810 | 0.811 | 1.420 |

| M_Acceptance | ||||

| Busy | 0.671 | 3.170 | 1.245 | 1.313 |

| Manage | 0.975 | 3.530 | 0.980 | 1.313 |

| TE_Dedication | ||||

| Inspire | 0.864 | 4.490 | 1.032 | 1.769 |

| Enthusiasm | 0.871 | 4.510 | 0.952 | 2.050 |

| Proud | 0.806 | 4.500 | 1.215 | 1.600 |

| TE_Vigor | ||||

| Energy | 0.858 | 3.920 | 1.282 | 2.042 |

| Gotowork | 0.690 | 4.340 | 1.006 | 1.278 |

| Vigorous | 0.895 | 3.970 | 1.159 | 1.892 |

| TE_Absorption | ||||

| Immersed | 0.876 | 4.150 | 1.121 | 1.222 |

| Intensity | 0.810 | 4.760 | 1.014 | 1.222 |

Reliability and Validity

The reliability analysis of this scale gave a respectable Cronbach alpha of 0.724 for awareness and 0.656 for acceptance (see Table 3). Churchill (1979) suggests 0.6 as a benchmark for reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) of the two constructs was 0.64 and 0.70, respectively. The composite reliability of the awareness and acceptance was 0.843 and 0.810, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha of the dedication, vigor, and absorption were 0.804, 0.755, and 0.598, respectively. The AVE and CR of the three constructs were 0.718, 0.884, 0.671, 0.858, and 0.711, 0.831, respectively. The threshold for the AVE and CR are ‘> 0.49’, and ‘> 0.70’. The AVE of the constructs confirmed the convergent validity. The Cronbach’s alpha and CR confirmed the reliability of the constructs.

| Table 3 Construct Reliability and Validity | ||||

| Cronbach's alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | Average variance extracted (AVE) | |

| M_Acc | 0.656 | 1.394 | 0.819 | 0.700 |

| M_Aw | 0.724 | 0.736 | 0.843 | 0.642 |

| TE_A | 0.598 | 0.613 | 0.831 | 0.711 |

| TE_D | 0.804 | 0.814 | 0.884 | 0.718 |

| TE_V | 0.755 | 0.828 | 0.858 | 0.671 |

After examining the convergent validity, the discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell-Larcker Criteria. Discriminant validity refers to the degree to which a construct varies from the other empirically. Therefore, the square root value of each construct’s AVE should be greater than the correlations with other latent constructs. Table 4 shows that discriminant validity is established.

| Table 4 Discriminant Validity (Fornel-Lackner Criteria) | |||||

| M_Acc | M_Aw | TE_A | TE_D | TE_V | |

| M_Acc | 0.837 | ||||

| M_Aw | 0.383 | 0.801 | |||

| TE_A | 0.171 | 0.432 | 0.843 | ||

| TE_D | 0.164 | 0.42 | 0.741 | 0.848 | |

| TE_V | 0.185 | 0.431 | 0.67 | 0.663 | 0.819 |

| Mean | 3.540 | 3.740 | 4.220 | 4.510 | 4.080 |

| SD | 0.607 | 0.529 | 0.835 | 0.904 | 0.952 |

The direct effect of awareness on dedication (β = 0.812, p < .001), on vigor (β = .730, p < .001), and on absorption (β = .779, p < .001) was positive and strongly significant; therefore, hypotheses H1a1, H1a2, and H1a3 are supported. The direct effect of acceptance on dedication (β = -.137, p < .05) was significant but possessed a negative directionality. The direct effect of acceptance on vigor (β = -.137, p > .05) was negative and not significant. The direct effect of acceptance on absorption (β = .040, p > .05) was positive but not significant. Therefore, hypotheses H1b1, H1b2, and H1b3 are not supported.

Discussion of Study 1

This study examines the impact of each construct of mindfulness on the three dimensions of work engagement among Gen Z. The results of this study are interesting because though mindfulness and work engagement have been studied in the literature (Kotze & Nel, 2016), but a deeper level of investigation among the respective dimensions has received less attention.

This study finds that awareness significantly and positively impacts dedication, absorption and vigor. This implies that as the awareness of an individual increases, their dedication towards the work, absorption related to the aspects of the work, and vigor to conduct the work increase. Awareness helps reduce cognitive load and promotes present-moment focus, thereby sustaining the vigor needed for work engagement. Vigor has a positive effect on performance as the employee approaches work with higher energy which increases their capacity for action, thereby enabling them to achieve work goals more easily (Owens et al., 2016). The broaden-and-build theory of Fredrickson (2001) posits that positive effects broaden the cognition and attention range, therefore employees in a positive mind frame are inclined to see the big picture and thus approach work with a holistic perspective (Diener et al., 2020).

However, an increase in acceptance may lead to an inverse impact on dedication. At work, acceptance may be coerced due to organizational imperatives, leading to the negative directionality of impact. Similarly, acceptance may not necessarily translate to enhanced vigor. However, the impact of acceptance on absorption may be positive, due to the inherent relationship between acceptance and absorption, but the impact may not be significant.

Thus, awareness of the work requirements and the related rationale may cause higher engagement of the individual with the work. The relevance of this research is high for organizations employing Gen Z workers, as the findings can be of significant utility value to their management by providing them specific inputs to enhance engagement and, thereby, the performance of the young employees. To achieve this, the organization needs to have a sharper focus on the application of mindfulness on the individual constructs of work engagement, namely absorption, dedication, and vigor.

A key limitation of Study 1 is that the observed effects may be influenced by variations in the time spent on social media, as suggested by Puukko et al. (2020). As the work engagement of Gen Z can be influenced by social media usage, study 2 was undertaken.

Study 2

The conceptual model for this study is given below (see Figure 1).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The questionnaire was sent to 390 respondents across India using a purposive sampling technique. A total of 336 respondents submitted their responses to the questionnaires. 11 respondents had missing data in certain fields and therefore were removed. The final sample (See Table 5) consisted of 83 females (25.5% of the sample population) and 242 males (74.5% of the population). The data was analyzed using the SmartPLS 4 software package.

| Table 5 Demographic Details – Study 2 | ||

| Gender | ||

| Frequency | Frequency % | |

| Female | 83 | 25.5 |

| Male | 242 | 74.5 |

| Work Experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 72 | 22.2 |

| 1 to 2 years | 88 | 27.1 |

| More than 2 years | 165 | 50.8 |

| Education Level | ||

| Graduate-Academic (BA, BSc., Bcom., etc.) | 55 | 16.9 |

| Graduate-Professional (BE, BTech, MBBS, etc.) | 125 | 38.5 |

| Post-Graduate | 145 | 44.6 |

Material

Different individuals may have different motivations to use social media (Dhir et al., 2017). Among Gen Z, four major factors have been found as a rationale for social media engagement. These are connections, popularity, appearance, values and interests (Rodgers et al., 2021). The new motivation for social media use (MSMU) scale was developed by Rodgers et al. (2021), based on previous research by Dhir et al. (2017).

Social Media Usage

The measures for SMU were derived from the connections construct, which comprised 3 items, from the Motivations for Social Media Use scale (MSMU) as developed by Rodgers et al. (2021). In addition to the three items the respondents were asked to rank the means by which users of social media may be influenced.

Results

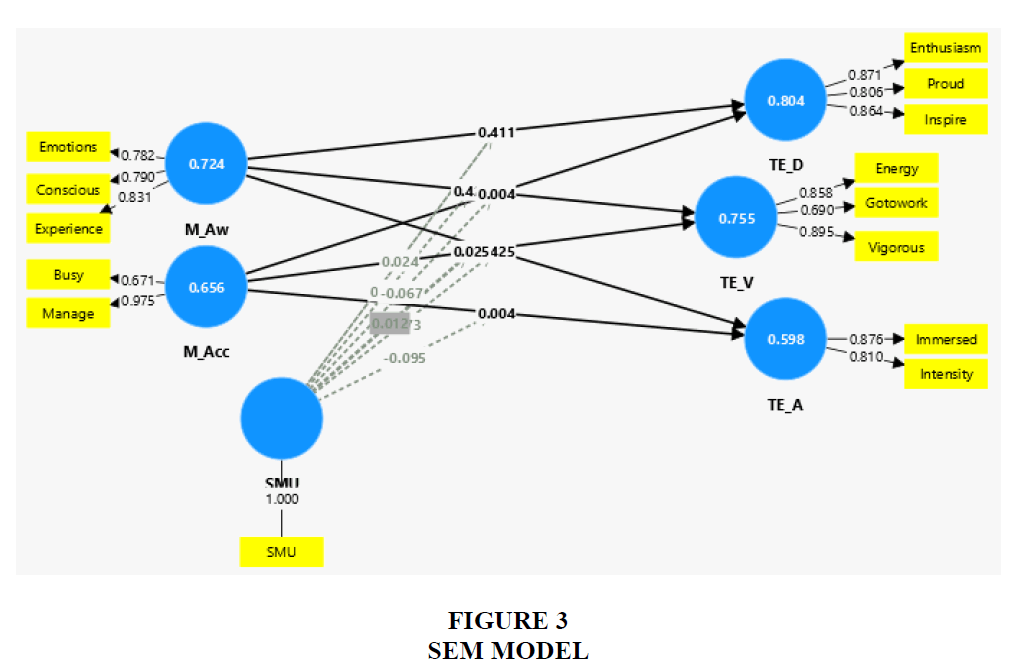

We developed a complete structural equation model (SEM) using the SmartPLS 4 software to test the hypothesized structural relations (see figure 2). We conducted a 5000 bootstrap run to find our results. The path model was a good fit per the recommended statistics (Hair et al., 2019). The standard root mean square residual (SRMR) value of the saturated model was 0.086, which is seen as an indicator of a good model fit (Henseler et al., 2014).

The indirect effect of SMU on the relationship between awareness and dedication (p > .10), and absorption (p>0.10) was insignificant. However, the indirect effect of SMU on the relationship between awareness (p<0.10) and acceptance (p<0.10) on vigor was mildly significant at a 10 percent significance level. In addition, awareness explained 15.26 percent of the change in vigor. As SMU increases, the moderating effect increases, as seen in Table 5. Thus, hypotheses H2c and H3c are supported.

The influence of SMU on the relationships between awareness and dedication, awareness and absorption, acceptance and dedication, as well as acceptance and absorption was not found to be significant (p >0.10), therefore hypotheses H2a, H2b, H3a, and H3b are not supported.

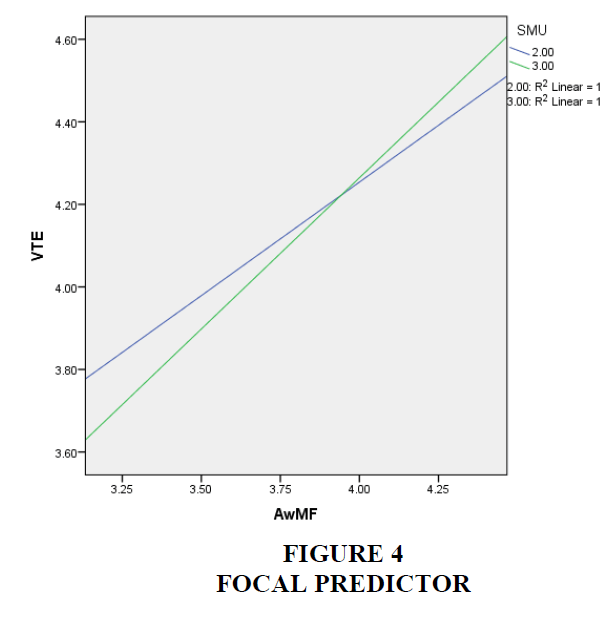

A 3 step hierarchical regression and the Johnson-Neyman technique, using the Andrew Hayes (2009, 2020) process to visualize the conditional effect of the focal predictor identified the two values of the moderator at which the slope of the predictor goes from non-significant to significant (see Figure 3). This is aligned with hypothesis H2b.

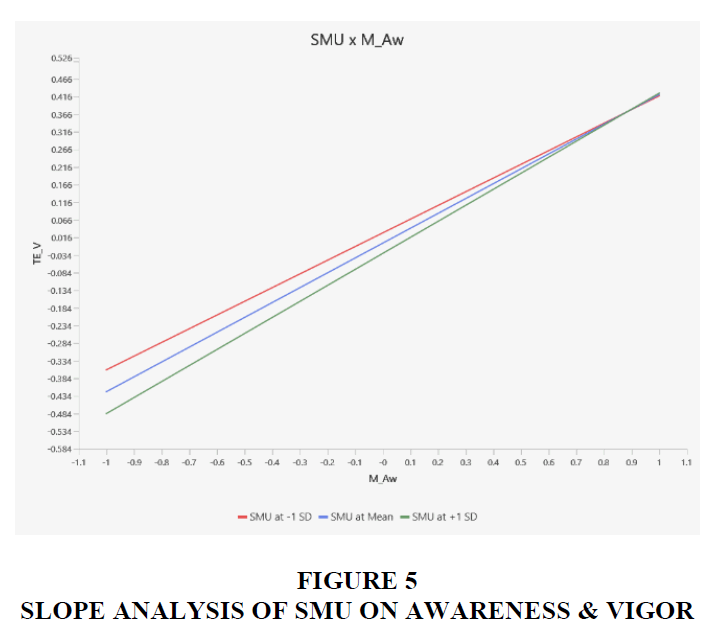

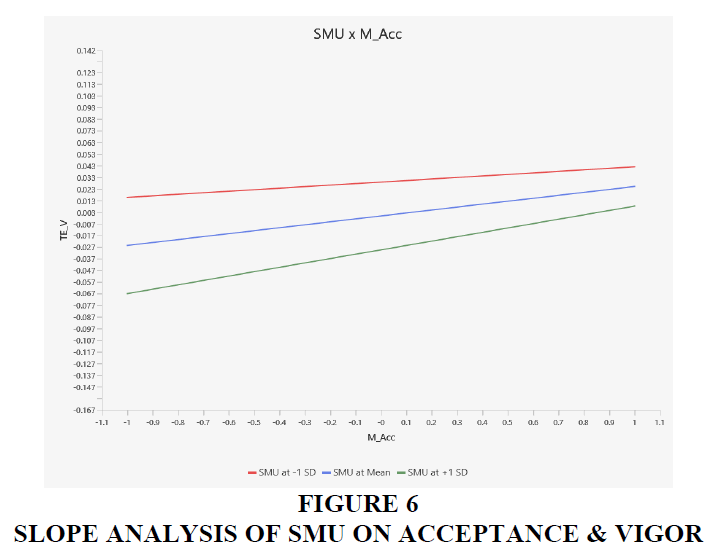

The slope analysis of the moderating impact of SMU on the relationship between awareness and vigor as well as acceptance and vigor reinforces the positive and mildly significant influence (see Figures 4-6). As SMU increases, its influence on the relationship increases.

Further slope analysis of the influence of SMU did not reveal any significant findings.

Discussion of Study 2

The study found significant moderation by SMU, of the relationship between the awareness construct of mindfulness and the vigor dimension of work engagement, as well as the acceptance construct of mindfulness and the vigor dimension of work engagement. The results of this study are interesting because though mindfulness and work engagement have been studied in the literature (Kotze & Nel, 2016), a deeper level of investigation among the respective dimensions has received less attention.

This study found that 15.26 percent of the relationship between awareness and vigor can be explained by SMU with a 93.07 percent confidence. The influence of awareness and acceptance on vigor increases with increased SMU. Vigor is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience, i.e., the willingness to invest effort in one’s work and persist even in the face of difficulties. Vigor is thus essential to improve work performance. Gonzalez-Roma et al. (2006) suggest that work engagement may be increased with high vigor. The positive association between awareness and acceptance with vigor established in this research is supported by existing literature. (Aikens et al. 2014)

This study extends the existing literature by examining the moderating effect of SMU on the relationship between the individual constructs of mindfulness and each dimension of work engagement. This study finds that SMU has a significant positive impact on the relationship between awareness and acceptance with vigor. This implies that social media can be leveraged to enhance awareness and acceptance of an individual, a Gen Z member in this context, thereby increasing their engagement with the work at hand. Previous studies have found that communication in social media supports work engagement via organizational identification and social support (Oksa et al., 2021).

In response to the question on the means by which users of social media may be influenced, the responses are provided in Table 6.

| Table 6 Means of Influencing Audience on Social Media | |||||||

| SN | Means of influence | Description | Rating | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | Influencers | Serve as role models, more attuned to the latest trends, resonate with Gen Z’s aspirations and foster a sense of connection. | 69 | 17 | 11 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | Viral or Emotional content | Content that elicits strong emotional responses amplifies its reach and influence, regardless of its accuracy or credibility | 12 | 58 | 22 | 7 | 1 |

| 3 | Gamification | Such as likes, shares, and rewards, to keep users engaged. | 8 | 51 | 36 | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | Algorithmic curation | The algorithms used by social media to personalize content for users. | 5 | 43 | 38 | 12 | 2 |

| 5 | Online communities | Belonging to these communities can shape values, and not being a part of them may create fear of missing out. | 4 | 17 | 22 | 52 | 5 |

| 6 | Sponsored content | Targeted advertising blended with organic content to make it challenging for users to distinguish between the two. | 2 | 11 | 19 | 31 | 37 |

General Discussion

The first construct of mindfulness, ‘awareness’, increases vigor and vigor augments goal achievement (Owens et al., 2016). The second construct of mindfulness, ‘acceptance’, is the free-will openness to the present moment without assumptions of how it should or should not be (Bishop et al., 2004). If the degree of acceptance is high, it enables the individual to cope with the present situation more easily, and therefore the individual can extricate oneself from a negative emotional state (Keng et al., 2016). Both awareness and acceptance can be developed at the workplace through MBIs. Such interventions can be periodic, sustained, online, as well as offline. Since Gen Z is more attuned to online communications and information sharing, it would be prudent to introduce online interventions for enhancing awareness and acceptance of work engagement. Practicing to be mindful can prevent burnout and increase vitality (Christopher & Maris, 2010).

Work engagement reflects a positive psychological state of mind. Individuals in organizations are engaged when they feel their work is of significance, and they take pride in their work. This is referred to as ‘dedication’ in the context of work engagement. The resilience and energy needed to face challenges stem from the construct ‘vigor’. The most prominent aspect of work engagement while investing efforts and persisting, is vigor (Sonnentag, 2017).When individuals are deeply immersed in work, they are said to be in a state of high ‘absorption’. These three constructs aggregate to form work engagement. The literature reveals that engaged employees demonstrate a higher degree of psycho-physiological well-being (Bakker, 2011), regularly complete tasks (Schaufeli et al., 2008), and contribute substantially to organizational effectiveness (Hoole and Bonnema, 2015).

This is highly relevant for managing Gen Z employees, as they mostly exhibit shorter job tenures due to their preference for novel work experiences (Ozcelik, 2015). Work engagement can be leveraged as a strategic tool to increase retention of these digitally proficient, and agile employees. This would enhance the organization’s productivity and competitive advantage.

Some of the recent studies conducted on social media usage and its effect on Gen Z include social influencers' impact on consumer behavior of Gen Z (Erwin et al, 2023), on sustainable behaviors among Gen Z (Confetto et al., 2023), on travel behaviors of Gen Z (Liu et al., 2023), customer experience of Gen Z in e-commerce (Tamara et al., 2023), purchase decisions of Gen Z (Fathinasari et al., 2023), and influencer marketing targeting Gen Z (Fan et al., 2023). However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association between the constructs of mindfulness with the individual dimensions of work engagement of Gen Z workers and to leverage influencers in social media for enhancing work engagement using mindfulness. Social media influencers play a pivotal role in driving opinions and behaviors of Gen Z consumers (Junaedi et al., 2023). These influencers are individuals who evolve into opinion leaders over a period of time and thus impact their followers on social media (Wahab et al., 2022). According to Wasserman and Madrid-morales (2021), perceived transparency and sincerity generated by the influencers as a result of sharing their achievements and failures builds an authentic rapport with their Gen Z followers.

This study is unique as it posits increasing work engagement of Gen Z workers using social media influencers. Such an approach is especially applicable to Gen Z as they are highly active on social media for their daily requirements, such as accessing information, networking with others socially, educating themselves, entertainment, and various other needs (Mude & Undale, 2023). The aim should be to encourage Gen Z to use social media responsibly. Since Study 2 shows that the most prominent means of influencing social media users is through the use of social media influencers, the influencers can be leveraged to generate awareness and acceptance of improving engagement with work.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

This paper makes several contributions. To the best of the authors' knowledge, it is one of the first quantitative studies to have explored the impact of individual constructs of mindfulness on the individual dimensions of work engagement.

The first academic contribution is that awareness and acceptance significantly impact vigor. Gen Z members need increasing clarity on any new initiative. This is enabled through awareness. Once they are aware, they are more likely to become enthused about the initiative. Their acceptance of the concept of work engagement imbibes them with more energy and therefore drives vigor. Thus, awareness and acceptance have a significant influence on vigor. The second academic contribution is to the body of mindfulness literature, through the examination of how the direct impact on individual constructs of work engagement may vary in intensity and significance due to the influence of the individual elements of the constructs of mindfulness. The third academic contribution is the finding that SMU moderates the relationship between the awareness and acceptance constructs of mindfulness and the vigor construct of work engagement. Such moderation is not witnessed in any other relationship between the constructs of mindfulness and work engagement. The fourth academic contribution is the proposition that influencers on social media may be leveraged to enhance awareness and acceptance of work engagement among Gen Z.

The research has several implications for practitioners. A key practical implication is to help Gen Z employees develop awareness and acceptance to ensure calmness and composure of mind. The association of mindfulness and work engagement can be of key importance to human resource professionals when Gen Z face high-pressure situations at the workplace, varied role expectations, and multiple job demands. Encountering such a diverse and demanding environment can be daunting for this generation of employees. By developing mindfulness, organizations can ensure a more seamless integration of Gen Z into an organization’s work environment. It is recommended that influencers be leveraged to enhance awareness. Using influencers to energize and enhance the vigor of Gen Z members would be a practical way of increasing the performance levels of the young workforce entering organizations across the world, thereby benefiting organizations worldwide.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Inquiry

As the sample for this study was limited to one country, future studies could compare the findings with samples of Gen Z workers in other geographical locations to expand generalizability. Another limitation is that this study did not distinguish between genders to study the gender-based differentiated impact of mindfulness on work engagement and its moderation by SMU. Future scholars may conduct similar studies considering gender specificity to understand the differentiated impact. Another limitation is the personal bias that could creep into this study as it was self-reported. Future researchers could collect data using cross-reporting mechanisms. Future researchers can use mixed methods, or experimental design and use qualitative study as confirmatory research, validating findings through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions involving Gen Z members and their supervisors or managers to validate the findings. Additionally, longitudinal studies could be conducted to study the impact of practiced mindfulness over some time.

Conclusion

Since awareness is the non-judgemental focused attention to the present, it can be generated through interventions at the workplace. This study recommends moving attention inward. Simple exercises such as closing eyes, taking deep and long breaths, and focusing attention on the sounds and smells of one’s surroundings, moving attention inwards, towards one’s breathing, body, and heartbeat leading to the stillness of mind can help increase awareness and acceptance, leading to better mindfulness at the workplace. An increase in mindfulness will have a significant positive impact on work engagement.

Gen Z are born digital and have access to digital devices since their early years which makes them comfortable using digital technology for accessing information, learning, entertainment, education, social networking as well as communication. Due to the plethora of information available on the internet, they seek authority figures, opinion leaders, or influencers online, to gain access to curated information. As a result, they frequently follow influencers on social media. This study explores the impact of SMU on the influence of mindfulness and work engagement among Gen Z employees.

The findings underscore that influencers can be leveraged to increase awareness and acceptance thereby infusing vigor in Gen Z to enhance engagement with work. Further, as awareness and acceptance increase with the moderation of SMU, vigor tends to increase. This research provides valuable insights to encourage the prudent use of social media to enhance Gen Z employees’ engagement with the work at hand. This study, to the best of our knowledge, is possibly the first to explore how social media influencers may be leveraged to enhance engagement with work among Gen Z workers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues and family for their support and encouragement throughout this study.

References

Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., & Bodnar, C. M. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 56(7), 721-731.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using selfreport assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current directions in psychological science, 20(4), 265-269.

Beaulieu, D. A., Proctor, C. J., Gaudet, D. J., Canales, D., & Best, L. A. (2022). What is the mindful personality? Implications for physical and psychological health. Acta Psychologica, 224, 103514.

Bishop, S.R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N.D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z.V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D. & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230-241.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Burnett, R. (2011). Mindfulness in schools: Learning lessons from the adults, secular, and Buddhist. Buddhist Studies Review, Vol. 28 (1), pp. 79-120.

Cardaciotto, L., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Moitra, E., & Farrow, V. (2008). The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment, 15(2), 204-223.

Chang, S. J., Witteloostuijn, A. V., & Eden, L. (2020). Common method variance in international business research. In Research methods in international business (pp. 385-398). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Christopher, J. C., & Maris, J. A. (2010). Integrating mindfulness as self-care into counselling and psychotherapy training. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, Vol. 10 (2), pp. 114-125.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64.

Confetto, M. G., Covucci, C., Addeo, F., & Normando, M. (2023). Sustainability advocacy antecedents: how social media content influences sustainable behaviours among Generation Z. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 40(6), 758-774.

Diener, E., Thapa, S., & Tay, L. (2020). Positive emotions at work. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 7(1), 451-477.

Duggan, L., Harvey, J., Ford, K., & Mesagno, C. (2024). The role of trait mindfulness in shaping the perception of stress, including its role as a moderator or mediator of the effects of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 224, 112638.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Erwin, E., Saununu, S. J., & Rukmana, A. Y. (2023). The influence of social media influencers on generation Z consumer behavior in Indonesia. West Science Interdisciplinary Studies, 1(10), 1040-1050.

Fan, F., Chan, K., Wang, Y., Li, Y., & Prieler, M. (2023). How influencers’ social media posts have an influence on audience engagement among young consumers. Young Consumers, 24(4), 427-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fathinasari, A. A., Purnomo, H., & Leksono, P. Y. (2023). Analysis of the Study of Digital Marketing Potential on Product Purchase Decisions in Generation Z. Open Access Indonesia Journal of Social Sciences, 6(5), 1075-1082.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron & Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication monographs, Vol. 76 (4), pp. 408-420.

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modelling of the contingencies of mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 64 (1), pp. 19-54.

Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2010). Digital natives: where is the evidence? British educational research journal, 36(3), 503-520.

Hong, Y. H., Lin, T. T., & Ang, P. H. (2015). Innovation resistance of political websites and blogs among Internet users in Singapore. Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 14(1), 110-136.

Hsu, M.-H., Tien, S.-W., Lin, H.-C., & Chang, C.-M. (2015). Understanding the roles of cultural differences and socio-economic status in social media continuance intention. Information Technology and People, 28(1), 224–241.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hu, S., Gu, J., Liu, H., & Huang, Q. (2017). The moderating role of social media usage in the relationship among multicultural experiences, cultural intelligence, and individual creativity. Information Technology and People, 30(2), 265–281.

Hyland, T. (2015). On the contemporary applications of mindfulness: Some implications for education. Journal of philosophy of education, 49(2), 170-186.

Indbiz.gov.in, 2021. One of the youngest populations in the world-India’s most valuable asset. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved from https://indbiz.gov.in/one-of-the-youngest-populations-in-the-world-indias-most-valuable-asset/. Accessed August 14, 2024.

Junaedi, A., Bramasta, R. A., Jaman, U. B., & Ardhiyansyah, A. (2023,). The Effect of Digital Marketing and E-Commerce on Increasing Sales Volume. In International Conference on Economics, Management and Accounting (ICEMAC 2022) (pp. 135-150). Atlantis Press.

Junca-Silva, A., Mosteo, L., & Lopes, R. R. (2023). The role of mindfulness on the relationship between daily micro-events and daily gratitude: A within-person analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 200, 111891.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hachette UK.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2016). Effects of mindful acceptance and reappraisal training on maladaptive beliefs about rumination. Mindfulness, 7, 493–503.

Klainin-Yobas, P., Ramirez, D., Fernandez, Z., Sarmiento, J., Thanoi, W., Ignacio, J., & Lau, Y. (2016). Examining the predicting effect of mindfulness on psychological well being among undergraduate students: A structural equation modeling approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 91, 63–68.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., Newton, F. B., Kim, E., & Wilcox, D. (2013). Psychosocial factors predicting first-year college student success. Journal of College Student Development, 54(3), 247–266.

Langer, E. J., & Ngnoumen, C. T. (2020). 27 Well-Being. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, p.379.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., & Carlson, L., et al. (2006). The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467.

Liu, J., Wang, C., Zhang, T., & Qiao, H. (2023). Delineating the effects of social media marketing activities on Generation Z travel behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 62(5), 1140-1158.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mann, R. B., & Blumberg, F. (2022). Adolescents and social media: The effects of frequency of use, self-presentation, social comparison, and self-esteem on possible self-imagery. Acta Psychologica, 228, 103629.

Mills, M. J., Culbertson, S. S., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Conceptualizing and measuring engagement: An analysis of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 519-545.

Morgan, M. C., Cardaciotto, L., Moon, S., & Marks, D. (2019). Validation of the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale on experienced meditators and nonmeditators. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 725–748.

Mude, G., & Undale, S. (2023). Social media usage: A comparison between Generation Y and Generation Z in India. International Journal of E-Business Research (IJEBR), 19(1), 1-20.

Oksa, R., Kaakinen, M., Savela, N., Ellonen, N., & Oksanen, A. (2021). Professional social media usage: Work engagement perspective. New media & society, 23(8), 2303-2326.

Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M., and Cameron, K. S. (2016). Relational energy at work: implications for job engagement and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 35–49.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of management, 12(4), 531-544.

Rodgers, R. F., Mclean, S. A., Gordon, C. S., Slater, A., Marques, M. D., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Development and validation of the motivations for social media use scale (MSMU) among adolescents. Adolescent Research Review, 6, 425-435.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research, Vol. 12, pp. 10-24.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schaufeli, W.B. & Bakker, A.B. (2008). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 293-315.

Schwieger, D., & Ladwig, C. (2018). Reaching and retaining the next generation: Adapting to the expectations of Gen Z in the classroom. Information Systems Education Journal, 16(3), 45.

Shahar, B., Britton, W. B., Sbarra, D. A., Figueredo, A. J., & Bootzin, R. R. (2010). Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Preliminary evidence from a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(4), 402–418.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shimazu, A., Schaufeli, W. B., Kosugi, S., Suzuki, A., Nashiwa, H., Kato, A., & Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, K. (2008). Work engagement in Japan: validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 510-523.

Silver, L., Huang, C., & Clancy, L. (2023). Key facts as India surpasses China as the world’s most populous country.

Skaugset, L. M., Farrell, S., Carney, M., Wolff, M., Santen, S. A., Perry, M., & Cico, S. J. (2016). Can you multitask? Evidence and limitations of task switching and multitasking in emergency medicine. Annals of emergency medicine, 68(2), 189-195.

Sonnentag, S. (2017). A task-level perspective on work engagement: A new approach that helps to differentiate the concepts of engagement and burnout. Burnout research, 5, 12-20.

Stuart-Edwards, A., MacDonald, A., & Ansari, M. A. (2023). Twenty years of research on mindfulness at work: A structured literature review. Journal of Business Research, 169, 114285.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tamara, C. A. J., Tumbuan, W. J. A., & Gunawan, E. M. (2023). Chatbots in E-Commerce: a Study of Gen Z Customer Experience and Engagement–Friend or Foe?. Jurnal EMBA: Jurnal Riset Ekonomi, Manajemen, Bisnis dan Akuntansi, 11(3), 161-175.

Tankovska, H. (2021). Number of global social network users 2017-2025. Statistics.Tschannen-Moran, M., & Gareis, C. R. (2015). Principals, trust, and cultivating vibrant schools. Societies, 5, 256–276..

Wahab, H.K.A., Tao, M., Tandon, A., Ashfaq, M. and Dhir, A. (2022), “Social media celebrities and new world order. What drives purchasing behavior among social media followers?”, Journal of Retailing and ConsumerServices, Vol. 68, p. 103076.

Wang, E. S.T. (2010). Internet usage purposes and gender differences in the effects of perceived utilitarian and hedonic value. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(2), 179–183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wheatley, D., & Buglass, S. L. (2019). Social network engagement and subjective well-being: a life-course perspective. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 1971-1995.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). A diary study on the happy worker: How job resources relate to positive emotions and personal resources. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(4), 489-517.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 30-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15674; Editor assigned: 31-Jan-2025, PreQC No. AMSJ-25-15674(PQ); Reviewed: 20- Feb-2025, QC No. AMSJ-25-15674; Revised: 26-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. AMSJ-25-15674(R); Published: 02-Apr-2025