Research Article: 2017 Vol: 16 Issue: 1

Understanding Chinese Consumers Purchase Intention of Cultural Fashion Clothing Products: Pragmatism Over Cultural Pride

Louisiana State University

Le Xing

Jiangnan University

Keywords

APEC, Chinese Style, Chinese Fashion, Cultural Pride, Ethnic Fashion, National Pride, Chinoiserie

Introduction

During the last few decades, the trade success in textiles and apparel has not only contributed significantly to China’s modernization, globalization, and economic success, but also helped cultivate its fashion industry. In the process of achieving economic success, China has nurtured the largest-consumer population with increasing desire for more fashionable clothing. The size of the market, 1.36 billion residents (China Population Statistic Report, 2015), plus the increasing spending power of many Chinese consumers, has attracted brands from the fashion world to expand market in China. The trend of chinoiserie which features Chinese traditional cultural elements and styles started when China’ economy took off (Clark & Milberg, 2011).

Meanwhile, a significant number of designers, manufacturers, and consumers in China appear to have gradually embraced the trend, making Asian chic a chic in China.

The on-going dynamic cultural interchange and interaction between China and the rest of fashion world increased national self-consciousness and the anxiety for recognition of Chinese culture and fashion design on the world stage (Finnane, 2005). Within the broad social and political environments, the Chinese fashion industry’s rapid development appears to be parallel with the linear progression of Chinese clothing styles’ changes and proliferations. In fact, the state played a leading role in clothing style diversification, directing and facilitating Chinese fashion industry development as well as affecting individual consumers’ consumption orientations (Sun, D'Alessandro, & Johnson, 2014; Zhao, 2013). On one hand, the Chinese government has significantly supported its fashion industry to give it a chance to show on the global fashion stage. On the other hand, the government support limits the Chinese fashion industry’s free creativity and innovativeness, which are critical to cultivating leading fashion designers and brands, and gaining recognition in the world fashion field (Schroeder, Borgerson, & Wu, 2015; Zhao, 2013).

The cultural interchange and interaction between China and the rest of world has not been balanced or even (Zhao, 2013). The Chinese styles and cultural heritage have been recognized as one of the most influential sources for Western designers to get oriental inspiration and create Asian chic (Yu, Kim, Lee, & Hong, 2001). Global brands have utilized Chinese-inspired designs and patterns to launch product lines catering to the rising wealthy Chinese consumers. However, China domestic market of culturally inspired fashion and fashionable ethnic clothing has been fragmented without internationally recognized leading brands or designers. For domestic fashion practitioners, historical and traditional Chinese cultural resources provide a great repertoire for creative designs, a cultural context for the product, and brand positioning with less international competition. However, without world recognition, the Chinese fashion industry has limited power to set trends utilizing and capitalizing on its rich cultural heritage (Finnane, 2005).

Dress is among the most visible symbols of cultural interchange and communication. For most cultures, ethnic clothing is also a symbol of identity and a basic means of communication among people of commonality (Roach-Higgins & Eicher, 1992). With the increasing economic success and national self-consciousness, the desire for a national dress to represent the national spirit and identity and boosting the cultural economy of fashion industry, get stronger among state leaders and Chinese fashion industry practitioners. In the early 21st century, when China was experiencing enormous growth and becoming increasing confident in its encounter with the West, the state took the opportunity to host for the first time the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit and invented a national dress called the Tangzhuang, trying to reflect both traditional Chinese flavor and modern ideas (Zhao, 2013). The created style increased the awareness of ethnic identification and promoted consumption of ethnic clothing among Chinese consumers. However, the state-led project to create a national dress and set an ethnic fashion trend failed because of a lack of sustainable purchase by Chinese consumers, indicating that market forces might play the more significant role than the state on developing Chinese fashion industry.

With the increasing modernization and globalization in China, the concept of fashion democracy which is against the concept that fashion is only defined by fashion powerhouses, instead, promotes the freedom of accepting and even creating fashion and trends by independent individuals, has been accepted by more Chinese fashion consumers. Consequently, the successes of developing and growing Chinese fashion industry, fashion brands, and even fashioning national identity depends significantly on consumers’ purchase intention (Thompson & Haytko, 1997). It is very critical to scrutinize consumers’ motivations for engaging in culturally related consumption. Without a stable and growing domestic market for Chinese ethnic fashion, the trend of Chinoiserie will eventually become demeaning.

To this end, this research intends to examine Chinese consumers’ purchase intention of ethnic fashion, which was sponsored by the Chinese state. Eicher and Sumberg (1995) define ethnic dress as “ensembles and modifications of the body that capture the past of the members of a group, the items of tradition that are worn and displayed to signify cultural heritage.” The authors define ethnic-inspired fashion as fashionable clothing designed and created based on inspiration from ethnic costumes with fashionable elements added following previous research (Veena & Sharron, 2008). Specifically, the most recent international event hosted in China, the 2014 APEC, was considered as an ethnic fashion promotion platform (Zhao, 2013) and the 2014 version of APEC garb was selected as the study subject. This paper examined the relationships among cultural pride, perceived practical usefulness, fashion leadership, attitudes, and purchase intention of ethnic fashion. We also explored whether there is any impact of endorsement by the international event of the 2014 Beijing APEC by examining the moderating effects. Practically, such understanding is needed for a growing domestic and global market, establishing national brands, nurturing Chinese designers with recognition from the rest of the fashion world, and for global fashion brands to expand market in China.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Conceptual Model

This study proposes a composite model incorporating the Theory of Reason Action (TRA) and Katz’s functional theories of attitude (Katz, 1960). The TRA model, typically referred as the Fishbein model, has been broadly and intensively applied across numerous social behaviors. According to the TRA, consumer attitude is the powerful predictor of their behavioral action. According to Schlosser and Shavitt (2002), behavioral intention is based on attitude toward the behavior, which constitutes an individual’s evaluation of the behavior. Attitudes can be defined as an overall positive or negative evaluation of attitude objects. Previous researchers have confirmed that attitudes have a strong, direct and positive effect on intentions (Dabholkar & Bagozzi, 2002). By incorporating the TRA into the functional theory of attitude to understand the significance of attitude, one must focus on the functional or motivational base of the attitude.

Katz (1960) argued that attitudes are formed based on an individual’s expectation of the object to serve some functions to meet the person’s different needs including utilitarian, value-expressive, knowledge and ego-defensive needs. According to Katz (1960), attitudes serve a knowledge function, facilitating an individual to organize and structure his or her environment and provide a sense of understanding and consistency in one's frame of reference. Knowledge function was considered as the most fundamental function attitudes serve. According to some researchers, all attitudes serve knowledge function to some degree, further indicating the importance of knowledge function. From the viewpoint of knowledge function, having attitudes toward products or issues can provide a reassuring sense of understanding and facilitate individual’s decision-making. In the context of fashion consumption, consumers’ attitudes toward a new fashion serve a knowledge function through providing a reassuring sense of identifying and communicating correct trends, styles with the majority of others, that is, showing individuals’ fashion leadership. According to Hirschman and Adcock (1987), fashion consumers can be divided into two groups, fashion leaders based on their fashion knowledge, credibility in fashion communication, and the sense of keeping personal style fashionable. Researchers refers to leaders as individuals who are more involved with fashion, usually purchase new styles the first, like to take risks, have more knowledge about fashion trends, and are confident in their choices. Overall, fashion leaders are considered product specialists who provide other consumers with information about a particular product class.

Regarding the utilitarian function, Katz (1960) argued that attitudes reflect individuals’ need to maximize rewards and minimize punishments obtained from objects in one's environment. A fashion product attitude would serve this function to the extent that it summarizes the positive and negative outcomes one associate with the fashion product (e.g. self-image, trendy look) and guides behavior that obtains or avoids those outcomes (e.g. outdated look, tarnished self-image). Attitudes also play an important role in self-expression and social interaction. Through the attitudes, an individual consumer holds and discuss, the individual expresses his or her central values, establish self-identity and gain social approval. This social role of attitudes can be referred as the social identity function (also labeled the value-expressive function by Katz) and it is of obvious relevance to attitudes toward a fashion product. For example, one's attitude toward a cultural fashion-clothing product may be seen as symbolic of one's ethnic identity and may be publicly expressed in order to convey a favorable, patriotic image to others (Schlosser and Shavitt, 2002). Wearing fashionable ethnic clothing may signify some important symbolic meanings about individual’s self (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001).

Based on the above review and discussion of literature, we applied Katz’s (1960) functional attitude theory and conceptualized knowledge, utilitarian, and value-express functions as meeting consumers’ needs to portray fashion leadership, getting a right look for special occasions, and express cultural pride through wearing culturally inspired fashion clothing products. According to Schlosser and Shavitt (2002), a lack of methods for operationalizing attitude functions has hampered the empirical progress of functional attitude theory for several years. Identifying or manipulating functional attitude theories in different consumer related contexts will facilitate the empirical progress of these theories. Therefore, this current research intends to search and test methods to operate functional attitude theories to shed light on understanding the functioning of fashion consumer attitudes. Specifically, we conceptualize knowledge function as reassuring sense of individual’s fashion leadership, utilitarian function as having more chances to use or wear a fashion clothing product to maximize rewards from wearing in different situations, self-expressive function as expressing individual cultural or ethnic identity. Consequently, we proposed that individuals’ perceived practical usefulness, cultural pride and fashion leadership affect their attitudes toward a cultural fashion-clothing product, and in turn affect their purchase intention.

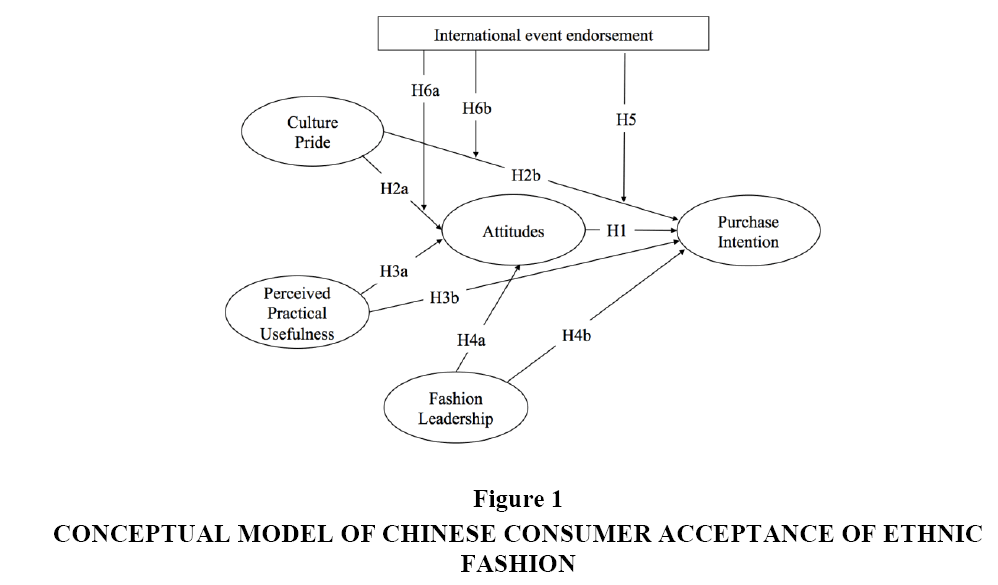

As mentioned earlier, the Chinese state has become deeply involved in its fashion industry using the government’s power to interact with market forces. The new government regime has called for achieving the Chinese dream by cultivating national and cultural pride among consumer-citizens through continually improving the nation’s identities and image on the global stage. Consequently, in the current study the conceptual model also argued that situational factors such as the government-sponsored international event might shape the relationships among individuals’ cultural pride, attitudes, and purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model of this study. It is consistent with the extant literature and will be used to guide the following discussion, hypotheses development, and empirical study.

Culture Pride

The term cultural pride derives from the terms of national pride and nationalism. National pride was defined as “individuals’ sentiments of pride directed towards the nation-state based on their national identity” (Evans & Kelley, 2002; Pang, 2011). National pride is different from nationalism. According to Billig (1995), national pride is mainly about individual attitudes towards the nation-state. Nationalism contains not only individual attitudes but also an ideology, which is about unity among members of society (Pang, 2011). Cultural pride is mainly about individual attitudes towards the nation’s culture and ethnic identity without the nation’s current ideology. According to Gordon’s (1992) research on native people in the US, a loss of cultural heritage and ethnic identity has made it difficult for native people to feel pride about who they are or have strong self-esteem. Many scholars believe that individuals’ cultural pride is in line with ethnic identity. In this study, we specifically refer to culture pride as individuals’ positive attitudes toward their cultural heritage and resources and feeling proud to have an ethnic identity associated with a specific culture.

Fashion has proved to be an important platform to show cultural pride and an individual’s ethnic identity. In the study about Chinese Americans, Jorae (2010) suggested that unique clothing and objects associated with ethnic group culture often attracted mainstream society observers; therefore, for many immigrants, clothing became a tangible symbol of their status as foreigners and represented an outward symbol of cultural identity. Kim and Arthur (2003) studied Asian American consumers’ attitudes towards ethnic apparel by investigating if the consumers used it as a sign of pride of their cultural heritage and if they were likely to wear it on different occasions. The researchers found that individuals who identified more strongly with their ethnic identities also held more positive attitudes towards cultural products and were more willing to use cultural products for different occasions.

Perceived Practical Usefulness of Cultural Fashion Clothing Products

Some scientists explored four types of criteria emerged as the important factors including aesthetics, usefulness, performance and quality. The usefulness components are important in affecting the purchase intention of consumers. Fashion clothing is a possession that holds a significant position in society (Chakrabarti & Baisya, 2009). Especially, cultural fashion clothing products signify some important symbolic meanings and individual identity, and it is used to express the wearer’s self (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001). Perceived practical usefulness refers to occasions for an individual to expect to wear ethnic fashion to fit better into the occasions or get more attention that is positive. In an empirical study, Forney and Rabolt (1986) investigated the relationship between ethnic identification and use of ethnic dress among seven ethnic groups in the San Francisco Bay area. They measured usage based on where and when the participants wore the ethnic dress and whether such usage signified pride in their ethnic background. Their study found that consumers who scored high on the ethnic identity measure also reported greater use of ethnic dress. Previous research also found that the particular occasion is one of the most significant factors for an individual to make a purchase decision on ethnic clothing (Chakrabarti & Baisya, 2009). Chinese clothing styles are frequently used as a symbol of Chinese culture and identity. For example, the Qipao is widely regarded as the archetypal, traditional costume of the Chinese nation (Köll, 2010; Reinach, 2011). It is an indispensable dress for Chinese brides on their wedding days.

Fashion Leadership

Fashion is a social process and individual fashion consumption is susceptible to interpersonal influence (Kim & Hong, 2011). Fashion leaders play a key role in the adoption and diffusion of new fashion. Goldsmith, Freiden & Kilsheimer (1993) described such leaders as those individuals who learn about new fashion trends earlier than the average consumers learn and purchase new fashion items soon after they are introduced into the market. Fashion leaders are usually the first to try new ideas and new styles in fashion and are innovators and opinion leaders with regard to fashion adoption and diffusion (Goldsmith et al., 1993; Workman & Johnson, 1993). Fashion leaders are considered product specialists who provide other consumers with information about a particular product class. Previous studies suggested that fashion leaders are more attentive to social cues than fashion followers (Laurent & Ronald, 2006). One of the important social cues in China is state call or government endorsement. Individuals with higher fashion leadership may be more conscious of the social changes initiated by the state regarding fashion and styles.

Situational Factor: State-Hosted International Event

Under a succession of media bombardments of stirring national achievements, such as the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the 2010 Shanghai Expo and the 22nd APEC meeting, the past several years have witnessed surging waves of national pride among Chinese people (Jacobs, 2008; Tony, 2009). According to Kuhn (2010) “Pride is the first guiding principles that energize a great deal of what is happening in China today” (p.20). Chinese pride, as a fundamental characteristic, often influences diverse policy development. The Chinese President Xi, Jinping addressed and vows to achieve the great renewal of Chinese nation (Anonymous, 2012). From President Xi’s viewpoint, pride in Chinese history "is the historical driving force inspiring people today to build the nation." (cf., Lawrence, 2010), and Chinese history and cultural heritage should be made the "driving force" to inspire and motivate Chinese citizens to further develop their nation's industries and economy to realize the Chinese dream (Wang, 2014). In fact, the connection between nationalism, social structure, and cultural heritage with dress has always been prominent in the history of China. For instance, in her book Chinese Fashion from Mao to Now, Wu (2009) described a principle being promoted by the state among Chinese consumer-citizens, and accepted the rising Chinese design stars “the more national, the more international”.

APEC is a forum for 21 Pacific Rim member economies that promotes free trade throughout the Asia-Pacific region (Elek, 1991). APEC has kept an unusual tradition for more than a decade. World leaders gather to take a “family photo” wearing the traditional dress of the hosting country to reflect its culture and tradition. More importantly, the leaders stand together in front of the world media, united in attire, displaying and symbolizing to the world an image of solidarity among the heads of state attending the APEC (Rose & Edwards, 2008). Overall, APEC costume is a great concert of global culture and national identity.

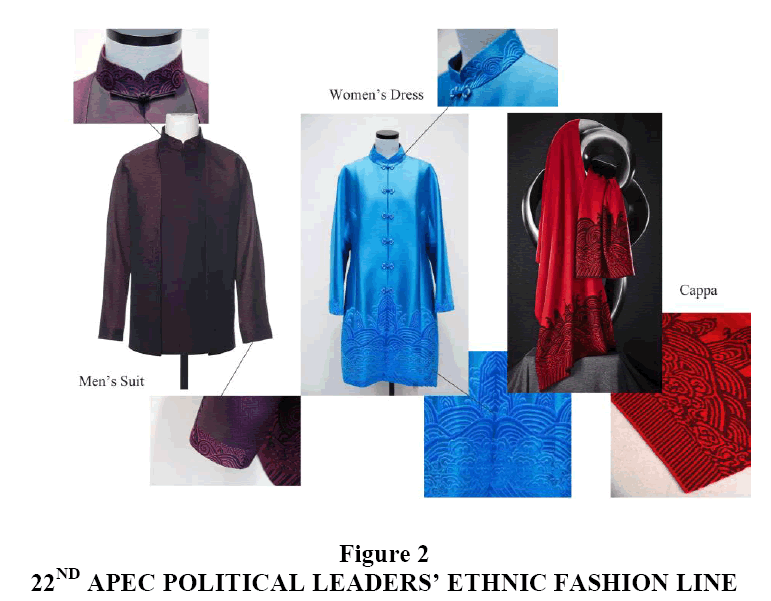

In 2014, China entered the so-called new economic normal characterized by relatively lower economic growth. Facing the slowing down of economic growth, the state has shifted focus to the quality rather than speed of economic growth, concentrating efforts on the cultural advancement and the revival of traditions (Jiao, 2015). The 22nd APEC meeting was held in Beijing November 10, 2014, under the new regime of President Xi. It was considered a great platform to promote Chinese culture and show national identity. The municipal government of Beijing, the host city, sent out a call for APEC garment design to universities around the country and the final official APEC dress synchronized elements from different design teams. The leaders in the 22nd APEC meeting wore bright colored Chinese style silk outfits, which delighted the public. Especially, the APEC style with Chinese characteristics worn by the first lady, Peng Liyuan, was considered a successful model of cross-cultural communication, and it won wide acclaim. The event boosted national confidence and cultural pride among Chinese citizens (Adiguna, 2013; Hilton, 2013; Perlez & Feng, 2013).

Research Hypotheses

Based on the above discussion, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Attitudes positively affect the purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products

H2: Cultural pride positively affects (a) attitudes towards and (b) purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products

H3: Perceived practical usefulness affects (a) attitudes towards and (b) purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products

H4: Fashion leadership affects (a) attitudes towards and (b) purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products

H5: The influence salience between attitudes and purchase intention of cultural fashion clothing products will be different across consumer groups with or without awareness of state endorsement via international event

H6: The influence salience between cultural pride (a) attitudes, and (b) purchase intention will be different across groups with or without awareness of state endorsement via international event.

Method

Research Design

An online survey was created using qualtrics.com. The first part of the survey included measures to assess individual characteristics including fashion leadership, cultural pride, and perceived practical usefulness. The second part included a group of 2014 APEC dress images (Figure 2). Participants were provided some descriptive words and requested to select those words that were associated with viewed dress images in their mind. Descriptive words including “APEC,” “Beijing APEC,” “Chinese style,” “traditional,” etc. Then, participants were requested to assess their attitudes towards, and purchase intention of, the viewed ethnic fashion line. The third part collected participants’ demographic information.

Measures

Research constructs were measured using multi-item scales using a seven-point Likert scale for two direction responses (e.g. disagree/agree) and five-point Likert scale for one direction response (e.g. never/very often) to capture as much variance as possible (Dawes, 2008). Measure assessing construct of cultural pride was adapted from Laroche et al.’s research (2007), which specifically focused on the cultural influence of ethnic identity on Chinese consumers’ decision-making. Three items consisting of the element of cultural/ethnic pride are selected and adapted. To increase construct validity, one item was added from the scale of national dis-identification adapted from Verkuyten and Yildiz (2007). A seven-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree) was used to rate the included four items.

Perceived practical usefulness was operationalized as perceived chances to wear cultural fashion for different occasions. Prior to this measure, a textual definition of ethnic fashion was provided. Following previous research (Veena & Sharron, 2008), visual stimuli which might not meet everyone’s ideal or exemplar of cultural apparel were not offered to define and describe cultural apparel. Following the definitions, four items adapted from previous research (Forney & Rabolt, 1986; Kim & Arthur, 2003). Participants were asked to assess the chances they would wear cultural apparel in general; as casual wear; for ethnic events, celebrations, or festivals; and for non-ethnic special occasions. Responses to these four one-direction items were assessed on a five-point Likert-type scale (1=Never; 5=very often).

Measures of fashion leadership are relatively similar across studies published through the years, and this study adapted four items from Hirschman and Adcock (1978). We measured participants’ attitudes toward the product using four seven-point semantic differential scales (the anchors were “like” versus “dislike,” “good” versus “bad” and “very favorable” versus “not favorable”) adapted from the scale used by Schlosser and Shavitt (2002). Reliability checks show a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92. Measures of purchase intention of ethnic fashion were created by researchers and assessed by a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=not likely at all; 7=very likely). Table 1 listed all the construct measures.

| Table 1 Measurement Assessment Results |

||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | EFA Item loading | Composite reliability | CFA Item loading | |

| Cultural Pride | 0.940 | 0.940 | ||

| My cultural/ethnic background has the most positive impact on my life | 0.82 | 0.937 | ||

| I feel very much attached to all aspects of my native/ethnic culture | 0.85 | 0.929 | ||

| I feel very proud of my cultural/ethnic background | 0.76 | 0.883 | ||

| I always have the tendency to distance myself from my background culture or ethnic identity a | ||||

| Perceived Practical Usefulness | 0.899 | 0.877 | ||

| Wear ethnic fashion for non-ethnic special occasions | 0.870 | 0.832 | ||

| Wear ethnic fashion as casual wear | 0.854 | 0.811 | ||

| Chance to wear ethnic fashion apparel | 0.849 | 0.793 | ||

| Wear ethnic fashion for ethnic events, celebrations or festivals | 0.798 | 0.767 | ||

| Fashion Leadership | 0.900 | 0.901 | ||

| Many of my friends and neighbors regard me as a good source of advice on clothing fashions | 0.891 | 0.880 | ||

| Often others turn to me for advice on fashion and clothing. | 0.852 | 0.874 | ||

| I am among the first in my circle of friends to try new clothing fashions. | 0.842 | 0.774 | ||

| I influence the types of clothing fashions my friends buy. | 0.838 | 0.801 | ||

| Attitudes | 0.921 | 0.783 | ||

| Not Favorable/Very Favorable | 0.882 | 0.921 | ||

| Not Valuable/Very Valuable | 0.880 | 0.870 | ||

| Bad/Gooda | 0.876 | |||

| Not Practical/Very Practical | 0.777 | 0.766 | ||

| Acceptance | 0.942 | 0.939 | ||

| Wear one or more pieces for myself | 0.885 | 0.827 | ||

| Purchase one or more pieces for myself | 0.859 | 0.827 | ||

| Recommend this collection to my friends or family members | 0.840 | 0.899 | ||

| Buy one or more pieces for my friends or family members as gift(s) | 0.814 | 0.875 | ||

| Share my wearing experiences with my friends on social media | 0.808 | 0.837 | ||

| Request my friend or family member to share their wearing experiences on social media | 0.808 | 0.828 | ||

| Note. CFA Item loadings and EFA Item loadings are based on the final measurement model a Item was deleted due to low communalities (<0.50) of EFA |

||||

Sampling and Sample

The survey was first subjected to pretesting. Feedback was separately obtained from two scholars in the field of consumer psychology research regarding the wording of the questions, the clarity of each statement, whether any relevant constructs were omitted, and the layout of the survey. Modifications were made based on feedback. Then a pilot testing was conducted using a convenience sample of 46 college students to assess the measurement properties of the constructs. An analysis of the responses from the second pretest confirmed that the constructs were one-dimensional and reliable, with alpha levels of 0.70 or above (Hair et al., 2009).

The final revised and proofed online survey was administered to a convenience sample recruited through the snowballing approach. Participants were invited by emails with the URL of the online survey embedded, enabling them to go directly from the e-mail to the survey page with a single click. A reminder email was sent a week after the initial invitation. An incentive of lottery prizes was offered to encourage a higher response rate. Among the total of 391 responses, 252 were completed and included into data analysis, representing a response rate of 64.45%. After the elimination of invalid responses, 243 valid responses remained for inclusion in empirical testing.

Of the participants, more than 62.4% were female. A majority of respondents were in the age range of 18-35, with 37.2% in the age range of 18-25 and 45.5% in the age range of 26-35. More than half of the respondents (55.8%) stated that their annual household incomes were less than RMB50, 000. Around 19.8% of the respondents had annual household income in the range of RMB 50,000-100,000. The rest of respondents (22.4%) had annual household income more than RMB100, 000. A majority of respondents had a four year college education or graduate degree, with 65.4% of respondents having post-college degrees. Only 9.9% of respondents reported not having the four-year college education. The sample was a little biased toward a population with higher education. In fact, the majority of cultural fashion consumers in China are females with higher education and in the age range of 18-54. Therefore, our sample was representative of the ethnic fashion consumer population.

Of the participants, more than 62.4% were female. A majority of respondents were in the age range of 18-35, with 37.2% in the age range of 18-25 and 45.5% in the age range of 26-35. More than half of the respondents (55.8%) stated that their annual household incomes were less than RMB50, 000. Around 19.8% of the respondents had annual household income in the range of RMB 50,000-100,000. The rest of respondents (22.4%) had annual household income more than RMB 100,000. A majority of respondents had a four year college education or graduate degree, with 65.4% of respondents having post-college degrees. Only 9.9% of respondents reported not having the four year college education. The sample was a little biased toward a population with higher education. In fact, the majority of cultural fashion consumers in China are females with higher education and in the age range of 18-54. Therefore, our sample was representative of the ethnic fashion consumer population.

Results

Measurement Assessment

All of the scale items measuring constructs were subjected to a series of exploratory factor analyses (EFA) by using Principal Axis Extraction (PCA) and varimax rotation (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2009). Eigenvalues and Scree plots were used to determine the number of factors to be extracted. As indicated in Table 1, one item from cultural pride and one item from attitudes were deleted due to high cross-loading (higher than 0.40) (Hair et al., 2009). The final EFA solution had a total of 20 items that measured five factors and accounted for approximately 79.75 % of the total variance. All communalities ranged between 0.69 and 0.91 and Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.90 to 0.94, demonstrating the reliability of the scales. All the EFA loadings, from 0.76 to 0.91, were reported in Table 1.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood was conducted on the 20 indicators of five latent constructs to further ensure the measurements’ reliability and validity. The initial results of the CFA model showed that the fit was within the acceptable thresholds (χ2/df=2.62, p<0.001, RMSEA=0.08 and CFI=0.93) based on Hair et al.’s (2009) criteria. As reported in Table 1, each item loaded significantly on its proposed constructs with composite reliabilities above 0.80, providing evidence of the reliability of the measures (Hair et al., 2009). Checking modification indices found two pairs of items with high error correlations within the construct. A correlation path was added to the two pairs of items. The final CFA model showed that the fit was great (χ2/df=1.724, p<0.001, RMSEA=0.055 and CFI=0.97; GFI=0.90). Therefore, the results showed that the internal consistency of multiple indicators for each construct was good. The average variance extracted (AVE) values (Table 2), which ranged from 0.64 to 0.84, exceeded the recommended value of 0.50. All standardized CFA loadings were significant (p<0.001) and exceed 0.60 (ranging from 0.77 to 0.94), showing strong convergent validity (Hair et al., 2009).

| Table 2 The Comparison Between Square Root of Aves and Correlations | |||||

| Cultural Pride | Perceived Practicality | Fashion Leadership | Attitude | Acceptance | |

| Cultural Pride | 0.840 b | ||||

| Perceived Practicality | -0.091 | 0.642 | |||

| Fashion Leadership | 0.269 | 0.147 | 0.695 | ||

| Attitude | 0.242 | 0.213 | 0.267 | 0.727 | |

| Acceptance | 0.397 | 0.180 | 0.347 | 0.541 | 0.721 |

a Correlation coefficients are estimates from CFA. All correlations are significant at p<0.001.

b Diagonal elements are AVE

Direct Effects Testing

Structural equation modeling (Hair et al., 2009; Kline, 2011) was used to test the research model and hypotheses. The model achieved an excellent fit to the data (χ2=263.31, df=157, χ2/df=1.72, p<0.001, GFI=0.906; CFI=0.971, RMSEA=0.053). With a good fit for the overall model, we turn our attention to the individual relationships contained within the model. H1 addressed the relationship between attitude and purchase intention. Results (Table 3) showed salient effects between attitude and purchase intention (β1=0.41, p<0.001), supporting H1. H2 addressed the effects of cultural pride on attitude (H2a) and purchase intention (H2b). The results supported both hypotheses: specifically, cultural pride positively affected attitude (β2a=0.212, p<0.001) and purchase intention of cultural fashion (β2b=0.264, p<0.05). H3 addressed whether or not perceived practical usefulness affects attitudes toward and purchase intention of cultural fashion. The SEM results showed significant effects on attitude (β3a=0.206, p<0.001), but not on purchase intention (β3b=0.093, p>0.05). Therefore, perceived practical usefulness affected attitude positively and H3 was partially supported. H4 addressed whether or not fashion leadership facilitated the formation of favorable attitudes toward, and purchase intention of, a cultural fashion line. Based on the SEM results, fashion leadership showed significant impact on both attitude (β4a=0.18, p<0.05) and purchase intention (β4b=0.15, p<0.05). Therefore, H4 was supported

| Table 3 Summary of Direct Effects Testing Results |

|||||

| Relationship within proposed research model | Path coefficient | Hypotheses | Testing results | ||

| Attitude | ➝ | Acceptance | 0.43** | H1 | Supported |

| Cultural pride | ➝ | Attitudes | 0.21* | H2a | Supported |

| Cultural pride | ➝ | Acceptance | 0.20** | H2b | Supported |

| Perceived practical usefulness | ➝ | Attitudes | 0.18** | H3a | Supported |

| Perceived practical usefulness | ➝ | Acceptance | 0.05 | H3b | Not Supported |

| Fashion leadership | ➝ | Attitudes | 0.19** | H4a | Supported |

| Fashion leadership | ➝ | Acceptance | 0.18** | H4b | Supported |

| Model fit indices | GFI=0.906; CFI=0.971; χ2/df=1.68 RMSEA=0.053 |

||||

* p<0.001; * p<0.05

Moderating Effects Testing

The sample was classified into two groups with participants based on whether participants recognized the viewed ethnic fashion line was 2014 APEC garb (Figure 2). Then group comparisons were conducted following the approach suggested by Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002). Six models were run comparing the group, which recognized APEC dress with the group that did not. Model A had all factor loadings constrained across the two groups, and error variances of the items for endogenous variables were constrained. Model B had the factor loadings free but error variances constrained. Model C had both error variances constrained, Model D had factor loadings constrained but error variance free. Model E had structural weights, and structural residuals constrained. Model F had structural weights free, but structural residuals constrained. The first test compared Model A to Model D, NS results showed significant χ2 difference (χ2=45.45; df=12; p<0.001). The second test compared Model B to Model, results also showed significant χ2 difference (χ2=73.97; df=23; p<0.001). According to some researchers, “if the amount of measurement error in the dependent variable varies as a function of the moderator, then the correlations between the independent and dependent variables will differ spuriously” (p. 1175). The third test compared Model E to Model F, results showed no χ2 difference (χ2=13.17; df=7; p=0.068), further showing no moderating effects found. Therefore, Hypotheses H5, H6a and H6b were not supported.

Discussion and Implications

The Chinese government played an important and unique role in the rise of Chinese textile and manufacturing industries. However, to cultivate Chinese cultural economy of the fashion industry, market forces rooted in consumers’ purchase intention also played a significant role. Consumers are essentially decision makers and thus have a tremendous impact on fashion product selection (Sibbel, 2003). This study makes the first attempt to empirically examine consumers’ purchase intention of state-sponsored ethnic fashion. Specifically, the aim of the present study is to contribute to investigate consumers’ attitudes and purchase intention towards ethnic fashion sponsored by the state in China.

The current study constructed a conceptual model with individual characteristics including cultural pride, fashion leadership, and perceived practical usefulness as exogenous variables; attitudes as a mediating variable; and purchase intention as an endogenous variable. In addition, we specified a state-sponsored event as a moderating variable. Empirical testing results showed that consumer attitudes positively affect their purchase intention of state-sponsored ethnic fashion. Cultural pride and fashion leadership were both found to positively affect consumers’ attitudes and purchase intention. However, the multi-group comparison found no cross-group difference, indicating that the state-sponsored event had no moderating effect on the proposed relationship among cultural pride, attitude and purchase intention. Therefore, the proposed conceptual model was accepted, except for the proposed path from perceived practical usefulness to purchase intention and the moderating relationships.

It is important to note that perceived practical usefulness positively affected consumers’ attitudes but not purchase intention. Our findings are consistent with previous research that examined relationships between fashion leadership and purchase intention of new fashion (e.g. Chakrabarti & Baisya, 2009; Workman & Johnson, 1993). We also found the influence of perceived practical usefulness on purchase intention was fully mediated by attitudes, consistent with the functional attitude theory (Katz, 1960) in that individuals form attitudes toward ethnic fashion based on their expectation of the ethnic fashion to meet their clothing needs for some occasions. Our findings also were consistent to some degree with Forney and Rabolt’s (1986) finding that the more occasions for wearing the ethnic dress were positively related to increased individuals’ usage of ethnic dress. Results also showed that cultural pride, directly and indirectly, affect individuals’ purchase intention of the state-sponsored ethnic fashion mediated through attitudes. These findings are fully consistent with the scholar Lawrence (2010), who argued that “in China, pride is drive.”

Findings from this study should help fill the substantial knowledge deficit that exists in cultural/ethnic/cultural fashion clothing products marketing in China. According to a study (Christine, 2013) about Chinese fashion, national identity and Chinese culture over the last few decades, Chinese designers are gradually moving from the periphery of the global fashion system toward its center. This study shows that contemporary Chinese fashion designers hark to a notion of “Chinese.” In the fashion industry, some global brands always have followed or created trends through the long history of Chinese culture or culture-inspired apparel. There is potentially a large market with more cultural products with Chinese characteristics and ethnic fashion for both domestic and global brands. Addressing cultural pride is very important when a global fashion brand penetrates or expands market in China.

The findings from this study also provide various implications for public policies, and companies, which have business in ethnic fashion or products with ethnic elements. To better promote ethnic fashion, public and social events or companies’ business marketing communications should connect cultural pride with promoted subjects. Furthermore, developing more national, provincial, or municipal cultural events to create more occasions for consumer-citizens to wear ethnic fashion to show their cultural pride will increase consumption of ethnic fashion. In fact, Chinese clothing styles have frequently been used as a symbol of Chinese culture and identity. For example, the Qipao is widely regarded as the archetypal, traditional costume of the Chinese nation (Köll, 2010; Reinach, 2010). It is an indispensable dress for Chinese brides on their wedding days. Nowadays, the occasions for wearing traditional ethnic clothing are rather limited. Anecdotal evidence showed that one reason for Chinese people to feel a lack of cultural experience is that there is a lack of rituals and occasions to show and enjoy culture and heritage.

Last, but not least, selecting influential fashion leaders to be endorsers are still an efficient and effective approach to diffuse new ethnic fashion styles and brands. For instance, Chinese actresses always generated waves of media attention and fads of all kinds of knock-offs every time they walked the red carpet with Chinese ethnic fashion. Peng Liyuan, China’s first lady has turned herself into a fashion icon since the first time she accompanied Xi on his first overseas trip as China’s new state president (International Business, 2013b). Fashion bloggers and journalists commented positively on Peng's style, triggering a frenzied Internet race to identify the brands she was wearing (International Business, 2013a). Peng’s style with Chinese characteristics, as a successful model of cross-cultural communication, has won wide acclaim. Increased advertising and endorsements by celebrities of ethnic fashion apparel in Asia fashion magazines and international awards ceremonies is another strategy to improve consumer awareness, draw their attention, and increase purchase willingness of ethnic fashion.

The current study has room for improvements, which suggest that different approaches for future studies may be useful. First, the sample was collected in the southeast region of China, which cannot represent the overall Chinese consumer population. China has 56 ethnic groups living 30 provinces. People from different regions have different cultural orientation and consumption patterns, especially in fashion consumption. Overall, people in south areas are considered more fashion conscious. Chinese domestic fashion companies and brands are mainly located in the south area. However, people living in northern areas are considered more likely to be affected by the state’s calls. Therefore, it is necessary to examine whether consumers’ purchase intention of ethnic fashion will be same across different regions.

Secondly, the empirical model needs to be further extended to include construct tapping social norms. China is considered as a collectivism-oriented nation. However, with Western brands diffusing and being adopted by more Chinese consumers, more Chinese consumers have accepted the concept of individualism. It is worthwhile to examine whether collectivism will still affect consumer purchase intention of ethnic fashion that shows group identity. Meanwhile, it is also necessary to examine how the consumer characteristics of acculturation to the global consumer culture (Carpenter, Moore, Alexander, & Doherty, 2013) interact with their purchase intention of native cultural products, such as ethnic fashion.

Furthermore, the country-of-origin effect is an important factor in apparel choice among Chinese consumers. Significant differences were found in consumers’ beliefs about garments made in different countries regarding attributes like attractiveness, fashionableness, price, fit, etc. Therefore, more specific marketing variables such as brand preference (global vs. domestic) should also be included in future studies.

Finally, this study did not examine the difference or similarities between different groups of the same nationality and cultural background, like Chinese consumers at home or abroad. With Chinese immigrating to other countries, the overseas market size of Chinese ethnic fashion has been increasing significantly. In line with the successful development of the Chinese fashion industry and promoting Chinese domestic fashion designers, future studies should be conducted to determine how the proposed conceptual model is applied to Chinese consumers living in other countries and how each model is different or consistent using a multi-group comparison test.

References

- Adiguna, J. (2013). “APEC first ladies treated to tour: Peng Liyuan takes center stage”, The Jakarta Post, October 8, retrieved from http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/10/08/apec-first-ladies-treated-tour-peng-liyuan-takes-center-stage.html (accessed December 27, 2015).

- Anonymous. (2012). “Xi pledges "great renewal of Chinese nation". Xinhua English News, November 11, Retrieved from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-11/29/c_132008231.htm.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal Nationalism. London; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Carpenter, J.M., Moore, M., Alexander, N., & Doherty, A.M. (2013). Consumer demographics, ethnocentrism, cultural values and acculturation to the global consumer culture: A retail perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(3/4), 271-291.

- Chakrabarti, S. & Baisya, R.K. (2009). The influences of consumer innovativeness and consumer evaluation attributes in the purchase of fashionable ethnic wear in India, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(6), 706-714.

- Christine, T. (2013). From symbols to spirit: Changing conceptions of national identity in Chinese fashion. Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, 17(5), 579-604.

- Clark, H. & Milberg, W. (2011). After T-bills and T-shirts: China's role in "high" and "low" fashion after the global economic crisis. Research Journal of Textile & Apparel, 15(1), 98-107.

- Dabholkar, P.A. & Bagozzi, R.P. (2002). An attitudinal model of technology-based self-service: Moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 184-201.

- Dawes, J. (2008). “Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales”. International Journal of Market Research, 51(1), 1-19.

- Eicher, J. & Sumberg, B. (1992). World fashion, ethnic, and national dress. Dress and ethnicity. Oxford, Washington, DC, 297-367.

- Elek, A. (1991). Asia pacific economic co-operation (APEC). Southeast Asian Affairs, 33-48.

- Evans, M.D.R. & Kelley, J. (2002). National pride in the developed world: Survey data from 24 nations. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14(3), 303-338.

- Finnane, A. (2005). China on the catwalk: Between economic success and nationalist anxiety. China Quarterly, 183, 587-608.

- Forney, J.C. & Rabolt, N.J. (1986). Ethnic identity: Its relationship to ethnic and contemporary dress. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 4(2), 1-8.

- Goldsmith, R.E., Freiden, J.B. & Kilsheimer, J.C. (1993). Social values and female fashion leadership: A cross-cultural study. Psychology & Marketing, 10(5), 399-412.

- Gordon, L.P. (1992). Ethnic identity, cultural pride, and generations of baggage: A personal experience. Arctic Anthropology, 29(2), 182-191.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. & Anderson, R.E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis (7 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hilton, W. (2013). A New Ambassador for Brand China. China Today, 62(6), 40-41.

- Hirschman, E.C. & Adcock, W.O. (1978). An examination of innovative communicators, opinion leaders and innovators for men's fashion apparel. Advances in Consumer Research, 5(1), 308-314.

- Jacobs, A. (2008). Even the cynical succumb to a moment of real national pride. The New York Times, August 8, Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/09/sports/olympics/09beijing.html?_r=0.

- Jiao, F. (2015). Prospects for the Chinese economy. China Today, 64(4), 26-29.

- Jorae, W.R. (2010).The limits of dress: Chinese American childhood, fashion, and race in the exclusion era. The Western Historical Quartely, 41(4), 451-457.

- Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 12.

- Kim, H.S. & Hong, H. (2011). Fashion leadership and hedonic shopping motivations of female consumers. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 29(4), 314-330.

- Kim, S. & Arthur, L.B. (2003). Asian-American consumers in Hawaii: The effects of ethnic identification on attitudes toward and ownership of ethnic apparel, importance of product and store-display attributes and purchase intention. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 2(1)1, 8-18.

- Kline, R.B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Köll, E. (2010). Changing clothes in China: Fashion, history and nation. Business History Review, 84(2), 403-405.

- Kuhn, R.L. (2010). How China's leaders think : the inside story of China's reform and what this means for the future. Singapore; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Laroche, M., Zhiyong, Y., Chankon, K. & Richard, M.O. (2007). How culture matters in children's purchase influence: A multi-level investigation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), 113-126.

- Laurent, B. & Ronald, E.G. (2006). “Some psychological motivations for fashion opinion leadership and fashion opinion seeking”. Journal of Fashion Marketing & Management, 10(1), 25-40.

- Lawrence, R. (2010). In China, pride is the driver. Business Week, 5-5. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=47380948&lang=zh-cn&site=ehost-live.

- Pang, Q. (2011). Chinese national pride and east Asian regionalism among the elite university students in PRC. Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 2(1), 28-55.

- Perlez, J. & Feng, B. (2013). China's first lady strikes glamorous note on her first trip in new role. retrieved from http://libezp.lib.lsu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgbc&AN=edsgcl.323425793&site=eds-live&scope=site&profile=eds-main.

- Reinach, S.S. (2010). Chinese fashion: From Mao to now. Journal of Asian Studies, 69(4), 1221-1222.

- Reinach, S.S. (2011). National identities and international recognition. Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, 15(2), 267-272.

- Roach-Higgins, M.E. & Eicher, J.B. (1992). Dress and identity. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 10(4), 1-8.

- Rose, M. & Edwards, L. (2008). Transnational flows and the politics of dress in Asia. ILAS Newsletter, 46(1), 3.

- Schlosser, A.E., & Shavitt, S. (2002). Anticipating discussion about a product: Rehearsing what to say can affect your judgments. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 101-115.

- Schroeder, J., Borgerson, J. & Wu, Z. (2015). A brand culture approach to Chinese cultural heritage brands. Journal of Brand Management, 22(3), 261.

- Sibbel, A. (2003). Consumer science: A science for sustainability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 27(3), 240-240.

- Sun, G., D'Alessandro, S. & Johnson, L. (2014). Traditional culture, political ideologies, materialism and luxury consumption in China. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 578-585.

- Thompson, C.J. & Haytko, D.L. (1997). Speaking of fashion: Consumers' uses of fashion discourses and the appropriation of countervailing cultural meanings. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(1), 15-42.

- Tian, K.T., Bearden, W.O. & Hunter, G.L. (2001). Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 50-66.

- Tony, B. (2009). China's new cultural revolution. The Wall Street Journal, Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com.hk/scholar?cluster=1955515858487756360&hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=2005&sciodt=0,5.

- Umberto. B. (2013a). China: Xi Jinping’s singer wife Peng Liyuan set to join world’s most influential first ladies. International Business Times, March 14, Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/xi-peng-liyuan-first-lady-kennedy-obama-446173.

- Umberto. B. (2013b). China’s first lady Peng Liyuan: A censors' headache. International Business Times, March 28, Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/china-peng-liyuan-censorship-tiananmen-square-451489.

- Veena, C. & Sharron, J.L. (2008). Ethnic identity, consumption of cultural apparel and self-perceptions of ethnic consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 12(4), 518-531.

- Verkuyten, M. & Yildiz, A.A. (2007). “National (dis)identification and ethnic and religious identity: A study among Turkish-Dutch muslims. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(10), 1448-1462.

- Wang, Z. (2014). “The Chinese Dream: Concept and Context”. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 19(1), 1-13.

- Workman, J.E. & Johnson, K.K. (1993). Fashion opinion leadership, fashion innovativeness and need for variety. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 11(3), 60-64.

- Wu, J. (2009). Chinese Fashion: From Mao to Now. Oxford; New York: Berg. 1221.

- Yu, H.L., Kim, C., Lee, J. & Hong, N. (2001). An analysis of modern fashion designs as influenced by Asian ethnic dress. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25(4), 309-321.

- Zhao, J. (2013). The Chinese Fashion Industry: An Ethnographic Approach. London, UK: A&C Black. 17-23.