Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 2S

Understanding Branding and Impulsive Buying Dynamics in Africa: A Quantitative Research on Consumers in the Context of Ghana

Théophile Bindeouè Nassè, University of Business and Integrated

Development Studies, Ghana / Saint Thomas D'Aquin University, Burkina Faso

Clement Nangpiire, University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana

Henry Opoku Adomako, University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana

Collin Agyemang, University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana

Rachid Abubakar, University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana

Citation Information: Nassè, T.B., Nangpiire, C., Adomako, H.O, Agyemang, C., & Abubakar, R. (2024). Understanding branding and impulsive buying dynamics in Africa: A quantitative research on consumers in Ghana. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(S2), 1-18.

Abstract

Purpose - Impulsive buying is another form of consumer behaviour that seems to be occurring more frequently today. This behaviour has positive and negative effects; therefore, caution should be taken when making consumption decisions. This study examines how branding, motivation and product price influence consumers' impulse buying behaviour. Design/methodology/approach - A combination of qualitative and quantitative research conducted to investigate the aim of the study. As part of the quantitative method, two hundred thirty-three respondents participated in a questionnaire survey with ages ranging from 10 to 40. The interviews' results assisted in forming the conceptual model of the study with the most important independent variables and the development of the study's research questions. Findings - According to the findings, branding has a significant association with impulse buying. Consumers are highly motivated to purchase impulsively, and motivation strongly influences buying. In addition, the findings show that product price is associated with impulse buying, and consumers make impulse purchases by considering the price. The research also reveals that gender and age have no significant association with impulse buying as consumers make impulse buying regardless of gender or age. Originality/value – This research paper’s interesting findings serve to remind managers and industry players to innovate in terms of branding, pricing, and customer relationship management. Practical implications – There should be a strong and a rigorous segmentation with a consideration of motivation in customer relationship management and innovative and affordable branded products to serve consumer’s expectations.

Introduction

Present day customers face daily realities on acquisition of products and services (Deepalakshmi, 2023). Organizations are tasked with various tasks today, keen on painful areas of strength and client connections (Mensah, et al. 2023). Organizations infuse weighty assets and time into the investigation of conduct and humanistic variables to acquire a lot of knowledge and to acknowledge designs. Consequently, brands address essential resources for organizations. The importance of branding has grown in recent years, and it is now seen as a crucial organizational resource. Impulse buying has been considered a significant consumer purchasing activity (Cobb and Hoyer, 1986; Mensah, et al. 2023). The variables setting off such buys are critical to comprehend, as most customers purchase without thinking occasionally (Silvera et al., 2008; Cobb and Hoyer, 1986). Today practically 70% of purchasing decisions are made at outlets and selling points (Heilman et al., 2002). Hao, Paul, Trott, Guo, and Wu (2021) portrays that planned purchasing conduct depends on judicious direction and is tedious.

Conversely, spontaneous purchasing incorporates buys without such pre-arranging and objective navigation. Consequently, firms are keen on understanding, anticipating, and fulfilling shoppers' requirements and needs on anything they like, desire, and anywhere they live (Schiffman and Kanuk, 2000). As Schiffman and Kanuk (2000), and Dangi, Gupta, and Narula (2020) indicated, consumer behaviour centres around how purchasers approach choices on spending their accessible assets, for example, time, cash, and exertion on utilization-related things. Consumer behaviour incorporates what is purchased, why it is purchased, when it is purchased, where it is purchased, how frequently it is purchased, and how often it is utilized (Schiffman and Kanuk 2000). Pandey (2005) contends that buying out thinking is developing rapidly. Branding is significant for persuading purchasing (Dangi, et al. 2020). Therefore, we need to investigate the impact of branding on impulse buying in Ghana. Accordingly, solid brands can produce long-haul and faithful clients, ultimately accelerating deals (Dangi, et al. 2020).

Zhou and Wong (2004); Hao et al. (2021) state that to get buyers in the ongoing competitive markets, retailers need to comprehend how they can draw in and hold a considerable portion of shopper motivation to buy with markings. Due to the challenges of managing brands and their benefits, this research focuses on a fundamental evaluation of marking and its function or impact on impulsive shopping in Ghana. These are the research objectives:

1. To determine the relationship between branding and impulse buying.

2. To examine the relationship between consumers’ motivation and impulse buying.

3. To identify the relationship between product price and impulse buying.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Culturalist Theory of Consumption: The culturalist view of consumer behaviour recognizes that a specific consumer's behavior is determined by their own culture (Nassè et al., 2019; Nassè, 2020; Mensah and Amenuvor, 2021; Jakubanecs et al., 2023). These authors have demonstrated that culture affects consumption in different sectors and in different dimensions. We know that culture plays a vital role in each life since culture is an individual way or a group way of life; it determines buyers' consumption behavior.

Thus, culture in the African context can motivate impulsive buying behavior as well as it can explain impulsive buying behavior

Conceptual Framework

Concept of Branding: Understanding the elements of branding and deciding its worth starts by examining it from different perspectives. Branding has been broadly utilized in business for many years, which unexpectedly led individuals to miss out on a definition that catches all parts of the brand. Individuals from various disciplines have created multiple ways to deal with the subject; a portion of the donors believe that brand is a name; some say that a brand is an item or, at times, a responsibility. Haralayya (2022) notes that stamping has been there for quite a while to perceive the results of one creator from those of another. According to the American Marketing Association (AMA), a brand is a "name, term, sign, picture, or plan, or a mix of them, expected to recognize the work and results of one vendor or social event of dealers and to isolate them from those of challenge". It is more than the moulding of peculiarity: it produces affiliations. Branding refers to an unmistakable item that is managed by a firm and that contains a mix of practical and emblematic qualities (Haralayya, 2022). Branding goes about as a banner, waving to shoppers, making familiarity with the item and separating it from different contenders (Hao, et al. 2021). The degree to which brands can discuss a message with the buyer is still under banter. Brands are critical to the message (Haralayya, 2022). The two perspectives stress the job of branding in typifying the importance of the worker and the customer. This joint significance shows that branding has created a kind of culture in shoppers after some time (Haralayya, 2022). Brands recognize the source or creator of an item and help buyers, either people or associations, to relegate liability to a specific producer or wholesaler. Customers might assess the indistinguishable item, ultimately relying upon how things are marked. Customers find brands through previous encounters with the item and its advertising program (Hao et al., 2021). They figure out which brands fulfil their necessities and which ones do not. As customers' lives become more confounded, surged, and time-starved, the capacity of a brand to improve on the direction and lessen the risk is essential (Haralayya, 2022).

To the buyer, brands give data concerning the degree of capability and representative execution and fulfilment they can anticipate in their relationship with a given brand (Hao, et al. 2021). Branding unwaveringness gives consistency and security of interest for the firm and makes boundaries that make it hard for different firms to enter the market.

Concept of Impulse Behavior

Consumer impulse purchasing attracted the consideration of researchers for a long time (Dangi et al., 2020). Since then, the examination zeroed in on the meaning of rash purchasing conduct. During the 1990s, specialists concentrated on the variables impacting buyer motivation. As per Redine, Deshpande, Jebarajakirthy, and Surachartkumtonkun (2023), drive purchasing is buying that is not anticipated, yet a visit to a store ends up in customers leaving a shop with at least one item purchased. In the view of Mensah et al. (2023), an arranged acquisition happens when the choice to buy occurs before entering the store. Motivation purchasing happens inside the store because of in-store excitement at the retail location. According to Rook (1987); Redine et al. (2023), consumers participate in drive purchasing conduct when they experience an unexpected yet strong and persistent desire to buy a specific item.

Concept of Consumer Motivation

Dangi et al. (2020) argued that choices are decided to accomplish specific points or closures; therefore, it is a significant thought in any purchaser's conduct. Inspiration influences not just the heading (influencing the decision of one direction over another) yet additionally the force of behaviour (limit portion on specific action) since individuals settles on decisions constantly. For Dabholkar, et al. (2003) consumer motivation refers to different individual reasons or factors that drive his/her preferences and choices. For Nassè (2018) consumer motivation refers to the different purposes or drivers for them to purchase some particular products that fit into their expectations and core needs.

Concept of Product Price

According to Kotler and Gertner (2002), price is the most accessible mixed marketing element for managing products exceptionally. For Nassè (2019) price is a form of contribution by the consumer in order to benefit from a product and its related services. Kusnanto, et al. (2023) find that price is a sacrificed input given in exchange for a product. Price also communicates with the market the placement of the value of a product referred to by the company. In the view of Kotler and Keller (2016), the price consists of four dimensions: affordability, suitability, conformability and competitiveness.

First, with the affordability of price, consumers can reach the price set by the company for a product. Generally, an item includes several types in a brand, but the price offered changes from a high-priced product to a low price. Secondly, price suitability with product quality can lure some consumers into choosing higher prices because they see differences in the quality of the products produced and between products with the high cost and lower costs. According to Kotler and Keller (2016), the higher the price of an item, the higher the quality of the good. Thirdly, price conformity with benefits usually entices consumers to buy a product based on the expected benefits generated from the product. If the product's perceived benefits are low, it will affect the consumer's decision and vice versa. Nassè (2022) highlighted that with price competitiveness, the product would compete well in the market. Consumers will often compare the price of a product with other similar products before buying it (Nassè, 2019).

Research Hypothesis

H1: Branding is strongly associated with impulse buying.

H2: Consumer motivation for impulse buying is strongly associated to impulse buying

H3: Product price is strongly associated with impulse buying.

Research Methodology

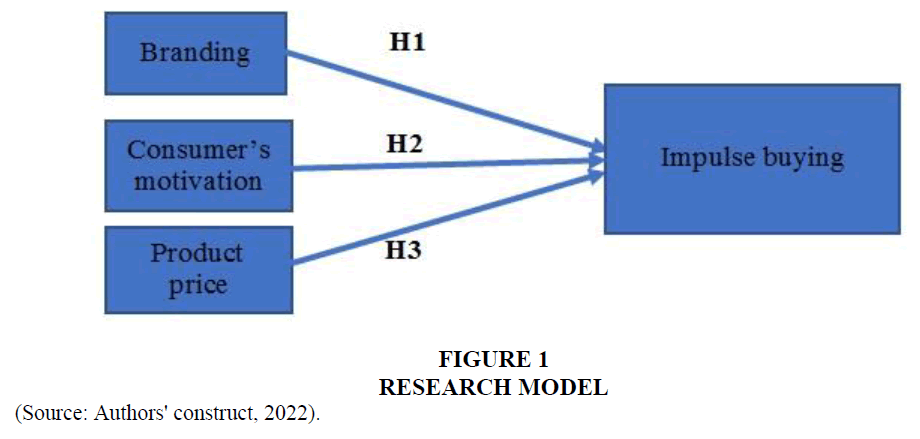

This depicts the instrument and methodology used to gather the expected information—optional information collected by auditing writing and examined by various writers. We are exploring such writing to help give more remarkable clarity and comprehension of the examination point. Saunders et al. (2003) indicated that optional information saves assets, for example, time and cash, which accordingly empowers the specialist to invest more energy and exertion in making examinations and translations of the data. The research was led to help in gathering essential information, utilizing a self-regulated survey. The research approach of the work is focused on a quantitative approach. A quantitative examination is a deliberate and logical strategy to explore peculiarities to apply a factual investigation Figure 1.

Sampling Size and Sample Frame

Sampling helps to exact data. Gathering information from a sample is less expensive than the whole populace. The populace chosen for the study is formed of individuals living in the Wa municipality. This is seen as the fitting populace for the survey. The comfort inspecting strategy, a non-likelihood testing method, is used to drive the assessment. Since the selection of responses is coordinated until the critical model size is reached, this technique grants fundamental authorization to the model layout. Additionally, it is thought to be less intense. However, because of how easy it is to obtain the instances in the model, this method tends to favour and produce outcomes that are outside the expert's expertise (Saunders et al. 2003). In terms of the inquiry, the sample size captures the general population. It includes the people to be consulted and the procedures that followed. A non-probability testing approach is used due to the nature of the topic under investigation and the geographic location of the respondents. Saunders et al. (2003) proposed that a bigger sample size decreases the probability of errors. In any case, a bigger sample size does not guarantee the exactness of results. For this research, 233 respondents are drawn from the Wa Municipal. The sample size, 233, was seen as a befitting sample size to acquire a thorough investigation.

Sampling Size

The sample size can be determined using the formula (Nassè, 2022): n ꞊ (p x (1-p)) / (e / 1.96)2 p = observed percentage and e = maximum error= 0.5 percent, what means that the observed percentage is 50%. n ꞊ (0.5 × (1 - 0.5)) / (e / 1.96)2 ꞊ 0.25 / (e / 1.96)2. The number of respondent for a maximum error of 6.5%, is n ꞊ 229 people. The total number of participants in the research is 233, which is broadly satisfactory and representative.

Validity and Reliability

Saunders et al. (2003) admit that the design of the requests, the development of the study, and the meticulousness of the pilot testing are all factors that affect the legitimacy and durability of the data gathered, as well as the response rate attained. Pre-testing the survey instrument assisted in determining the reliability and consistency of the compiled data. When the researcher sets up the survey with a clear understanding of the information requirements, when respondents interpret the requests in the same way a trained professional would expect, and when the examiner interprets the responses according to how the respondents arranged themselves, then both authenticity and constancy occur (Saunders et al. 2003). The elective construction process applied to spread out the enduring quality of the acquired data. By employing rigorously researched questions distinguished responses to a comparable request from optional types. An informal gathering of friends and partners is chosen for the pilot test to preserve authenticity. Additionally, several questions are altered from the survey used by Youn and Faber (2000) because they did not involve as much planning or buying.

Research Context

The research is focused mainly in the Upper West Region of Ghana with a probability sampling of 233 individuals with 5 Likert scale questionnaires.

Data Collection

For this research, the study technique is picked for information assortment. The overview strategy empowers collecting a lot of information from a sizeable populace. They are standardized, simplified and connected (Saunders et al., 2003). This outline assisted in utilizing an independent survey.

Questionnaire Design

A self-managed questionnaire was used to gather the essential information for the study. The study developed the inquiries in line with research of Youn and Faber (2000) on motivation purchase. The exploration goals were thought about during the development of every inquiry. The survey comprised four areas. Segment A (Motivation items) contained questions that would help in deciding how the branding of a particular item significantly affects their buying choices. Segment B (inspiration) include requests presumably to set off an impulsive attitude to acting. The respondents were given a quick summary of items from which to explore, places to find these items, the amount they were expected to pay for the items and the conditions that would foster the probability to drive the buying of the goods. In Segment C, the inquiries sought to distinguish the connection between item costs and how it causes consumers to buy. The questionnaires were close-ended. A few questionnaires comprised records (a few things presented for respondents to browse), classification (where just a single reaction should be chosen) and evaluations (where a rating gadget is utilized while recording responses). We assembled the rating questions using the Likert-style rating scale. There were five decisions open for respondents to peruse and tick where; 1 is strongly agreed, two is agreed, three is neither agree nor disagree, four has disagreed, and five strongly agree.

Data Analysis

The surveys were modified to ensure that respondents reply to all questions. Each question was mathematically coded after alteration to remove or reduce information errors. After that, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to handle the information. Different tactics were used to guide the research information. Recurrence classifications, factual systems for enumerating answers to specific questions, were also used for investigative purposes. These investigations are described using tables and figures.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical consideration can be determined as one of the main principles of the investigation. In the view of Nassè (2018), it is necessary to assure respondents of the anonymity, the privacy and the confidentiality of their responses. We ensured that these standard ethical considerations were activated during this study.

Data Analysis and Findings

Demographic Information Results

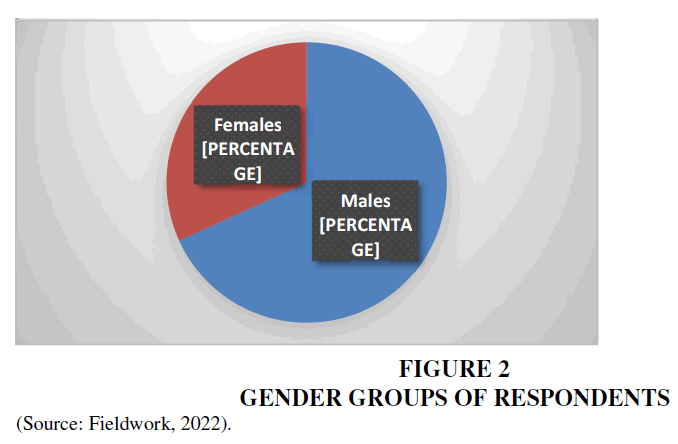

Gender groups, age groups, marital status, and professional status were the necessary socioeconomics for the study. The respondents' segment data was fundamental in accomplishing a portion of the examination targets. Figure 2 describes the respondents' orientation. Two hundred thirty-three people responded to the survey. 32% (81) were female respondents, while 68% (152) were male.

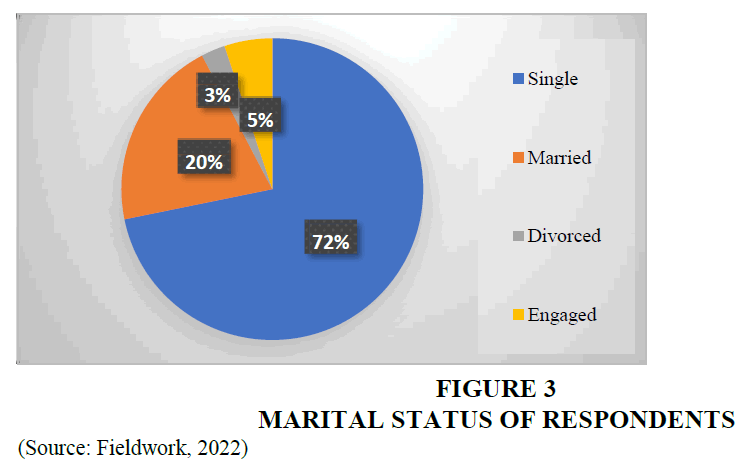

Figure 3 shows the marital status of the respondent. The finding shows that 72% are single, 20% are ma, married, 5% are engaged, and 3% are divorced.

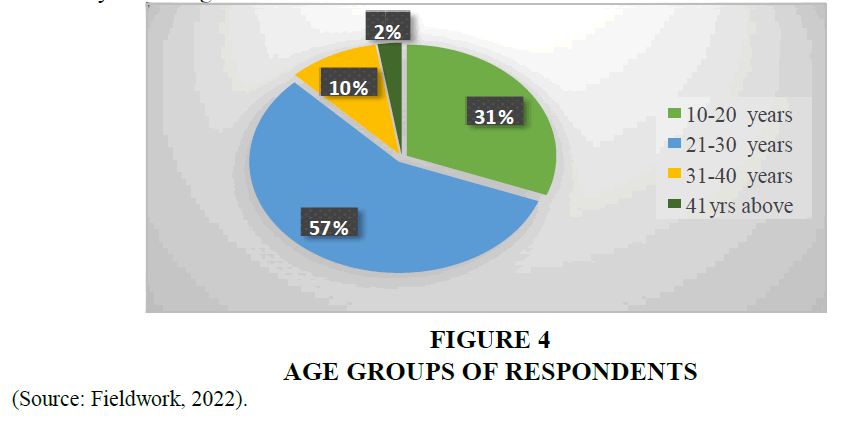

Figure 4 shows the respondents' diverse age range. The findings indicate that 57% of respondents were between the ages of 21 and 20. 31% of the respondents were between 10 to 20 years of age, 10% were between 31 years to 40 years of age, and just 2% were over 40 years o f age.

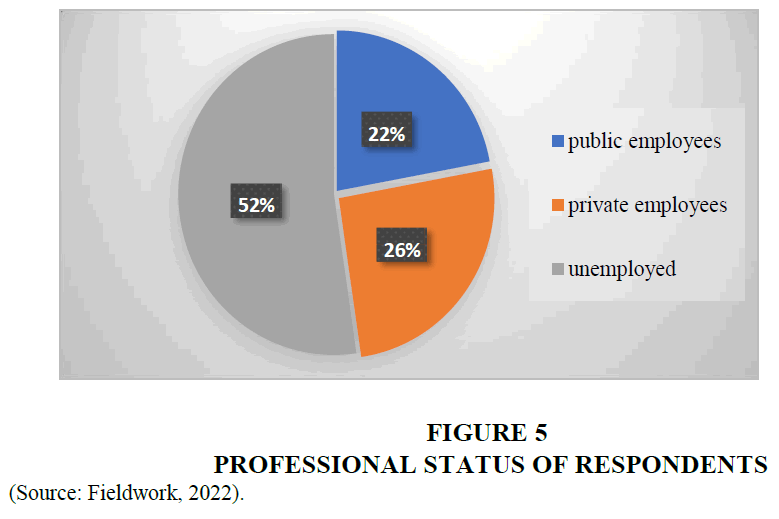

Figure 5 shows the professional status of the respondents. From the finding, 52% of the respondents are unemployed, 26% of the respondents are private employees, and 22% of the respondents are public employees.

Frequency Tabulations Results

Questions 1 and 2 asked respondents about their involvement in impulse items. The respondents are furnished with a rundown of things, from which they picked items they ordinarily buy by impulse.

Table 1 demonstrates the gender groups of the respondents tabulated with whether an individual buys the impulsive product. The findings show that 98 out of 152 male respondents believe that they buy impulse products, and 54 believe they do not buy sudden products. 70 out of 81 female respondents think they buy impulse products and 11 female respondents believe they do not purchase impulse products. According to Youn and Faber (2000), drive-ridden people are careless; they like to "improvise." Their decisions are made swiftly, and the changes they make nearby become apparent right away. When their bliss clashes with the truth of their circumstance or their definitive objective, they tend to seek out immediate fulfilment of their desires. It is apparent from the discoveries that male customers buy at motivation, which makes them more incautious while buying than female shoppers.

| Table 1 Percentage of Respondents | |||||

| Males | Percentage | Females | Percentage | Total | |

| Yes | 98 | 64.5 | 70 | 86.4 | 168 |

| No | 54 | 35.5 | 11 | 13.6 | 65 |

| Total | 152 | 100 | 81 | 100 | 233 |

On Table 2 the respondents were given a list of things and asked to choose the ones they would typically buy carelessly. The findings show that the primary motivational products were biscuits, candy, chocolate, chips, and chewing gum because these were the most popular selections. Sodas were only chosen sometimes. Although bread is bought with next to no preparation, none of the respondents conceded purchasing this item at the.

| Table 2 Products Bought at Impulse | ||||

| Valid | Frequency | Per cent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| D, E, G | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| A, D, E, G | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| , C, F | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| C, E, F | 3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 12.0 |

| C | 8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 28.0 |

| G | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 36.0 |

| B, D, F, G | 8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 52.0 |

| F | 17 | 34.0 | 34.0 | 86.0 |

| B, C, D, F, G | 6 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 98.0 |

| A, B, D, E | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 106.0 |

| A | 12 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 130.0 |

| D, F, G | 3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 136.0 |

| B, D | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 138.0 |

| B, D, F, G, H | 3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 144.0 |

| D | 9 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 162.0 |

| D, F, G, H | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 170.0 |

| A, B, D, E, F | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 172.0 |

| A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 174.0 |

| B, E | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 182.0 |

| B | 15 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 212.0 |

| B, D, F, G, H | 11 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 234.0 |

| E | 16 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 250.0 |

| F, G | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 252.0 |

| B, D, E, F, G | 2 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 256.0 |

| B, D, E, G | 9 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 274.0 |

| AN E, H | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 282.0 |

| B, G | 6 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 294.0 |

| A E | 5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 304.0 |

| B, C, D.F., G, H | 3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 310.0 |

| D, G | 8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 326.0 |

| B, D, F, G, H | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 328.0 |

| A, D, E | 8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 342.0 |

| B, D, F, G | 4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 350.0 |

| C, H | 3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 356.0 |

| A, C D, E | 5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 336.0 |

| A, B, E | 20 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 376.0 |

| B, F, G | 8 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 392.0 |

| A, B, C, E, F | 15 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 422.0 |

| B, C, D, E, F, G | 16 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 466.0 |

| Total | 233 | 466 | 466 | |

A=sweets D=fruits G=bread

B=biscuits E=chewing gum H=chips

C=chocolate F=soft drinks

Internal Consistency – Cronbach's Alpha

Cronbach's alpha was used to determine how closely connected the study question are that reflect each of the independent and dependent variables collectively. It accepts values between 0 and 1, with 1 denoting complete internal consistency. Compared to the readings below 0.7, a Cronbach's Alpha greater than 0.7 is dependable (Nunnally, 1978). The reliability of the variables' items was determined using Cronbach's Alpha test in SPSS Statistics. The research question's product pricing items exhibit high internal consistency because the alpha coefficient=0.888.

In the Tables 3-7, if one of the research question items is eliminated, it displays the updated Cronbach's value. The coefficient for the nine items that make up the independent motivation variable is 0.656, as shown in Table 3, which is lower than 0.7, and is not regarded as trustworthy. It is noted that if question item 11 is removed, the alpha coefficient will increase to 0.687. By preserving the remaining 8 question items, it is possible to create a group of closely similar elements that make up the independent motivation variable. The alpha coefficient is 0,873 concerning the internal consistency of the four question items for the dependent variable impulse buying. The alpha coefficient will rise to 0.883 if question item 22 is removed, offering higher internal consistency and reliability.

| Table 3 Alpha Cronbach of the Different Variables | ||

| Variable | Number of items | Alpha Cronbach |

| Branding | 4 | 0.800 |

| Motivation | 8 | 0.656 |

| Product price | 4 | 0.888 |

| Impulse buying | 4 | 0.873 |

| Table 4 KMO and Matrix for Branding | ||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| KMO | .657 | |

| Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 18.501 |

| Df | 6 | |

| Sig. | .005 | |

| Component Matrix | ||

| Component | ||

| 1 | ||

| I recognize a product through its brand | .359 | |

| I buy products with a brand name. | .696 | |

| When I have money, I buy branded products | .811 | |

| I like products with a well-branded name. | .773 | |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | ||

| a. 1 component extracted. | ||

| Table 5 KMO and Matrix Test for Motivation | ||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | .589 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 83.800 |

| Df | 36 | |

| Sig. | .000 | |

| Component Matrix | ||

| Component | ||

| 1 | ||

| When I am lonely, I frequently buy something in a shopping mall. | .766 | |

| I buy something on a whim because it makes me feel wonderful. | .539 | |

| Music makes me think about the things I enjoy. | .547 | |

| I make impulsive purchases during the holiday season. | .522 | |

| I never spend money on anything I did not plan to. | .568 | |

| My gender motivates me to make impulse buying. | .719 | |

| I make impulsive buying when I am happy. | .771 | |

| Friendship, family and travels motivate me to make impulsive buying. | .243 | |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | ||

| a. 1 component extracted. | ||

| Table 6 KMO and Matrix Test for Product Price | ||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | .485 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 5.822 |

| Df | 6 | |

| Sig. | .443 | |

| Component Matrix | ||

| 1 | ||

| I purchase low priced product. | .064 | |

| I purchase high priced products | .023 | |

| I buy moderate-price products. | .760 | |

| I make additional costs when I buy a product. | -.668 | |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | ||

| a. 1 component extracted. | ||

| Table 7 KMO for Independent Variables in One Analysis | ||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| KMO | .562 | |

| Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 235.541 |

| Df | 136 | |

| Sig. | .000 | |

Factor Analysis with Independent Variables in Separate Analyses

In the assessment, 4 items are presented comparable to the free factor marking. Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett's tests are led to check whether the information would be suitable for factor investigation. The data is qualified for factor examination assuming the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin advantage of exploring adequacy is higher than 0.5, and Bartlett's preliminary of sphericity is urgent with inspecting higher than 0.05. (Hair et al., 1995). The primary test yielded a worth of 0.657, with a raw p-value of 0.05. Subsequently, the information is reasonable for factor examination. The part lattice table shows that each of the things has strong loadings more prominent than 0.50, except for item 3, which does not add to the element with a value of 0.359.

For the independent variable motivation, the sample adequacy value for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test is 0.589 (>0.5), and the statistical significance of Bartlett's test for sphericity is 0.000. This indicates that factor analysis can be performed on the data. The component matrix table demonstrates that items 11 and 15 do not contribute to the factor because their loading values are below 0.5 (roughly 0.164 and 0.43).

In this research, 4 question items are related to the independent variable product price. Bartlett's test of sphericity is statistically significant (p=0.443), while the sample adequacy value calculated by Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin is 0.485 (0.5). This indicates that factor analysis cannot be performed on the data. The component matrix table shows that questions 16, 17, and 18 do not affect the factor because their loading values are less than or equal to 0.5 (0.064), (0.023), and (-0.668), respectively.

Factor Analysis with Independent Variables in One Analysis

The independent variables are subjected to one component analysis, what have produced three factors: one for question items 3-6, one for question items 7–15, and the third for question items 16–19. First, it was determined whether the data were suitable for factor analysis. It was established that they are appropriate for the investigation because Bartlett's test of sphericity is statistically significant (p=0.000), and the Kaiser-Meyer Olkin value of sample adequacy is 0.562 (>0.5) (Table 7).

Hypothesis Testing

Regression analyses are used to test the four hypotheses examined in the conceptual model. Regression analysis is a statistical tool that shows the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent factors while holding the other independent variables constant. It also estimates the value of the dependent variable when one of the independent variables changes value.

Linear Regression for H1

For premise H1, a linear regression analysis is performed. Testing is done on the associations between the independent variable of branding and the dependent variable of impulse buying. This regression model's R square is 0.657, which indicates that it accounts for 65% of the variance in impulsive purchasing. Additionally, the entire model is significant (F=5.169, p=0.001). The regression coefficients and their significance are shown in Table 8.

| Table 8 Regression Coefficients with Dependent Variable Impulse Buying | ||||||

| Coefficients | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.902 | .906 | 2.099 | .043 | |

| Gender | -.368 | .214 | -.230 | -1.723 | .094 | |

| Marital | .096 | .142 | .099 | .677 | .503 | |

| Age | -.184 | .180 | -.148 | -1.022 | .314 | |

| Profession | .059 | .140 | .059 | .422 | .675 | |

| Branding | .611 | .159 | .515 | 3.853 | .000 | |

As it can be seen in the table 8, as the p-value is less than 0.05, gender and age had no discernible influence on consumers' spontaneous purchases of branded goods. With a p-value of 0.00, branding does have a substantial effect on impulsive buying. As a result, branding does have an effect on impulsive behaviour, supporting hypothesis H1.

Linear Regression for H2

For premise H2, a linear regression analysis is performed. The associations between the independent variables of motivation and impulse buying are examined. This regression model's R square is 0.513, which indicates that it accounts for 51% of the variance in impulsive purchasing. Additionally, the entire model is significant (F=7.160, p =0.001). The regression coefficients and their significance are shown in Table 9.

| Table 9 Regression Coefficient of the Dependent Variable Impulse Buying | ||||||

| Coefficients | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | .773 | .926 | .834 | .410 | |

| Gender | -.267 | .200 | -.167 | -1.333 | .191 | |

| Marital | .106 | .131 | .110 | .812 | .422 | |

| Age | -.001 | .172 | -.001 | -.006 | .996 | |

| Profession | .012 | .128 | .012 | .093 | .927 | |

| Motivation | .727 | .152 | .622 | 4.793 | .000 | |

As seen on the Table 9, gender and age have no significant impact on impulse buying, some consumers tend to respond quickly and without reflection, and this is characterized by rapid reaction times, absence of foresight, and a tendency to act without a careful planning. Motivation does have a significant effect on impulse buying, with p-value=0.000. Thus, reason actually influences on impulse behaviour so hypothesis H2 is supported.

Linear Regression for H3

For hypothesis H3, a linear regression analysis is performed. Tests are done on the associations between the dependent variable impulse buying and the independent variable product price. This regression model's R square is 0.281, which indicates that it accounts for 28% of the variance in impulsive buying, with F=2.661, and pvalue=0.039, suggests that product price has a significant effect on impulse buying. The regression coefficients and their significance are shown in Table 10.

| Table 10 Regression Coefficients of the Dependent Variable Impulse Buying | ||||||

| Coefficients | ||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.776 | 1.141 | 1.556 | .129 | |

| P.P. | .437 | .203 | .334 | 2.148 | .039 | |

| Gender | -.243 | .254 | -.152 | -.959 | .344 | |

| Marital | .184 | .157 | .190 | 1.172 | .249 | |

| Age | -.172 | .203 | -.137 | -.844 | .404 | |

| Profession | -.014 | .156 | -.014 | -.092 | .927 | |

As seen in the table 10, gender and age have no significant impact on impulse buying; some consumers have the tendency to buy on impulse whether there is an increase in price or not. Other consumers tend to have the notion that when the price of a product is high, the quality of that product is high. Some consumers are susceptible to products with low prices. The table shows that the cost of the product cannot necessarily cause a consumer to buy on impulse. In some situational cases, companies can introduce price reduction promotions which can make consumers buy at impulse. The product price has a significant effect on impulse buying with pvalue=0.039. We can therefore reject the null hypothesis and say that there is a significant relationship between product price and impulse buying; therefore, hypothesis H3 is supported (Nassè, 2014).

Conclusion

This research aimed to look into how factors like product pricing, incentive, and branding affect impulsive buying. A significant sample size (233) of participants aged 10 to 40 participated in the survey. We used SPSS to run the test to examine each hypothesis independently. A linear regression analysis was first carried out to look at the central assumption of the study. The primary assumption indicates that consumers will display higher impulse buying for branded goods since the connection between branding and impulse buying is strongly significant (p-value=0.000). The initial hypothesis is thus accepted. The second hypothesis upheld that buyers will display higher impulse purchasing as they are motivated to make impulse buying. It was demonstrated from the outcomes that the connection between motivation and impulse buying is also strongly significant (p-value =0.000). The third hypothesis upheld that product price is strongly associated to impulse buying. The findings show that product price is strongly associated to impulse buying (p-value=0.039). Thus, the third hypothesis is confirmed. It was proposed that the cost of an item being cheap or expensive can influence customers to make the buying decision. The findings show that product price was crucial to impulse buying. In that regard, there is a relationship between consumers buying at high, low or moderate prices. From the findings, it is said that consumers make impulse buying when they need to and this is based on the cost of the item. It is observed that when price are low or affordable consumers are motivated to buy further. The central brain behind this study was to show how branding, motivation and product price affect impulse buying. The arrangement of the calculated model and the assessment of the three hypotheses gave an astute perception of the connection between the variables. A linear regression analysis was the measuring tool employed to discover this link. The first hypothesis was accepted, indicating that branding significantly affects impulse buying. The second hypothesis was also accepted, showing that the connection between motivation and impulse buying was critical. In addition, the third hypothesis was supported as product price has significant effect on consumers’ impulse buying. Finally, this research concludes that branding, motivation and product price positively influence consumers' impulse buying in the context.

Implications and Limitations

From the findings of this research, it is important for the company in the context to improve the quality of their brands to persuade both customers and consumers to purchase their products. It is also good for managers to have a good policy in terms of product pricing in order to attract consumers and therefore make more profits. In addition companies in the context, should adapt to customer needs and expectation through their marketing efficiency, good leadership and strategic positioning (Carbonell and Nassè, 2021) and the use of business intelligence practices (Ouédraogo et al., 2022). It is important for the government to put some good policies in order to regulate the market in terms of products pricing to ban overpricing decisions by some companies. The practices of fair pricing by companies is very crucial for their success and competitiveness (Nassè, 2022), because business fraud has proved to be very disastrous to business environments (Nacoulma et al., 2020). Thus, companies in the context should eradicate obstacles and use innovative strategies to better their performances (Wedam et al., 2022).

This study inspires further research, though the outcomes are not generalizable to the whole populace. The study used a single segment test, that is, college graduates between ages 10 to 40. As a result, more extensive research on buyers of various age groups should be conducted to make the findings suitable for generalization. Additionally, the number of respondents for the study was 233. This sample size is not significant enough for the population studied. The validity of the examination may be affected by an increase in the number of the sample size. Besides, a limit on the segment factors is noticed. In the exploration study, age, orientation, schooling and occupation were used as segment factors. Further investigation should be done on respondents' occupation, orientation, age, country of origin or ethnic group. This segment could influence the outcomes since consumers from various nations might introduce different drivers for buying and their triggers.

Acknowledgement

The researchers hereby acknowledge the efforts made by the various respondents, and the steady support of Dr. Théophile Bindeouè Nassè, Dr. Clement Nangpiire and the conspicuous editors of the Academy of Marketing studies Journal.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

Carbonell, L.N., & Nassè, T.B. (2021). Entrepreneur leadership, adaptation to Africa, organisation efficiency, and strategic positioning: What dynamics could stimulate success? International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(6), 1-10.

Cobb, C. J. & Hoyer, W. D. (1986). Planned versus impulse purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing, 62(4), 384-409.

Dabholkar, P.A., Michelle Bobbitt, L. & Lee, E. (2003). Understanding consumer motivation and behavior related to self scanning in retailing: Implications for strategy and research on technology based self service. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(1), 59-95.

Dangi, N., Gupta, S. K., & Narula, S. A. (2020). Consumer buying behaviour and purchase intention of organic food: A conceptual framework. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 31(6), 1515-1530.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Deepalakshmi, M. (2023). Impact of neuromarketing on consumer buying behaviour with reference to coimbatore city. Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications and Digital Marketing, 3740.

Giannopoulos, A.A., Piha, P.L., & Avlonitis, G.J. (2011). Desti-nation branding: what for? From the notions of tourism and nation branding to an integrated framework. In Berlin International Economics Congress.

Hao, A.W., Paul, J., Trott, S., Guo, C., & Wu, H.H. (2021). Two decades of research on nation branding: A review and future research agenda. International Marketing Review, 38(1), 46-69.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Haralayya, B. (2022). Effect of branding on consumer buying behaviour in Bharat Ford Bidar. Iconic Research and Engineering Journals, 5(9), 150-159.

Heilman, C. M., Nakamoto, K., & Rao, A.G. (2002). Pleasant surprises: consumer response to unexpected instore coupons. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 242-52.

Jakubanecs, A., Supphellen, M., Helgeson, J.G., Haugen, H.M., & Sivertstøl, N. (2023). The impact of cultural variability on brand stereotype, emotion and purchase intention. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 40(1), 112-123.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kotler, P., & Gertner, D. (2002). A country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. Brand Management, 9(4-5), 249-261.

Kusnanto, A. A., Rachbini, D. J., & Permana, D. (2023). Price perception, promotion, and environmental awareness with mediation of trust in purchase intentions for rooftop solar power plants (Adyasolar Case Study). Dinasti International Journal of Management Science, 4(4), 635-648.

Mensah, K., & Amenuvor, F.E. (2021). The influence of marketing communications strategy on consumer purchasing behaviour in the financial services industry in an emerging economy. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 27(1), 190 - 205.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mensah, K., Madichie, N., & Mensah, G. (2023). Consumer buying behaviour in crisis times: uncertainty and panic buying mediation analysis.

Nacoulma, L., Akouwerabou, L., & Nassè, T. B. (2020). The growing issue of business fraud in Burkina Faso: what best prevention device? International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 2(7), 437-457.

Nassè, T. B. (2019). Internal equity and customer relationship management in developing countries: A quantitative and a comparative study of three private companies in Burkina Faso. African Journal of Business Management, 13(1), 37-47.

Nassè, T. B. (2020). Religious beliefs, consumption and inter-religious differences and similarities: is syncretism in consumption a new religious dynamics? International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 2(2), 59-73.

Nassè, T. B. (2022). Customer satisfaction and repurchase: why fair practices in African SMEs matter. International Journal of Social Sciences Perspectives, 10(1), 26-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nassè, T. B., Ouédraogo, A., & Sall, F. D. (2019). Religiosity and consumer behaviour in developing countries: An exploratory study on Muslims in the context of Burkina Faso. African Journal of Business Management, 13(4), 116-127.

Nasse, B.T. (2018). Pratiques religieuses et comportement de consommation dans un contexte africain: une étude exploratoire sur les consommateurs au Burkina Faso (Doctoral dissertation, Thèse de Doctorat en sciences de Gestion, spécialité marketing).

Nassè, T.B. (2014). Internal equity as a factor of companies’ economic profitability. Saarbrücken, SA: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Nunnally, J.D. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Olins, W., & Hildreth, J. (2011). Nation branding: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination brands: Managing place reputation (3rd ed., pp. 5566). United Kingdom, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Ouédraogo, H., Compaoré, I., & Nassè, T. B. (2022). Practice of business intelligence by SMEs in Burkina Faso. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 4(1), 48-58.

Pandey, D. P. (2005). Education in rural marketing. University News, 43(1), 7-8.

Redine, A., Deshpande, S., Jebarajakirthy, C., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2023). Impulse buying: A systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(1), 3-41.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rook, D. W. & Gardner, M. P. (1993). In the mood: impulse buying's affective antecedents. Research in Consumer Behavior, 6(1), 1-26.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2003). Research methods for business students (3rd ed). Spain, SP: Prentice Hall.

Schiffman, L. G. & Kanuk, L. L. (2000). Consumer behaviour (7th ed). London, LO: Prentice-Hall International.

Silvera, D.H., Lavack, A. M., & Kropp, F. (2008). Impulse buying: the role of effect, social influence and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(1), 23-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wedam, K. C., Nassè, T. B., & Ackon, E. (2022). Innovation and obstacles in West African firms: an evidence from the Ghanaian context. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 4(11), 469-487.

Weinberg, P., & Gottwald, W. (1982). Impulse consumer buying as a result of emotions. Journal of Business Research. 10(1), 43-57.

Youn, S. & Faber, R. J. (2000). Impulse buying: Its relation to personality traits and cues. Advances in Consumer Research, 27(1), 179-185.

Zhou, L. & Wong, A. (2004). Consumer impulse buying and in-store stimuli in Chinese supermarkets. Journal of International Marketing, 16(2), 37-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 17-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13794; Editor assigned: 18-Jul-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13794(PQ); Reviewed: 26-Oct-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13794; Revised: 02-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13794(R); Published: 04-Dec-2023