Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 6S

Toxic Traits: Unpacking the Relationship between Personality and Workplace Bullying and its Repercussion

Samiksha Singh, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies (UPES), Dehradun

Sunil Rai, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies (UPES), Dehradun

Geeta Thakur, Manav Rachna University, Dehradun

Anurag Singh, University of Petroleum and Energy Studies (UPES), Dehradun

Citation Information: Singh, S., Rai, S., Thakur, G., & Singh, A. (2023). Toxic traits: unpacking the relationship between personality and workplace bullying and its repercussion. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(S6), 1-11.

Abstract

The rising prevalence of bullying in the workplace has been a major concern for organizations in recent times. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between personality traits and the consequences of workplace bullying among worker of automobile showrooms. A questionnaire was administered to 402 automobile showroom workers, and the findings indicated that the Big Five personality traits could predict victimization from workplace bullying. Notably, neuroticism emerged as a significant personality antecedent and was positively correlated with workplace bullying. The study also found that workplace bullying resulted in adverse consequences, including increased stress levels, reduced customer experience, and the intention to leave. The findings of this study may help organizations identify potential victims of bullying and implement measures to prevent victimization in the workplace.

Keywords

Workplace bullying, Customer Experience, Consequences, Personality Traits.

Introduction

The workplace is comprised of individuals from diverse cultural and personal backgrounds, resulting in a range of issues related to personality types. These issues include stress, counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs), and workplace marginalization and bullying. Bullying in the workplace has increased in modern business, leading to negative outcomes such as increased absenteeism, employee turnover, negative customer experience, and brain drain. Leymann (1996) defines workplace bullying as a continual and hostile aggressive behavior. Workplace bullying creates stress, which results from an individual's perceived inability to meet the demands of the work environment (Ongori & Agolla, 2008). Workplace victimization, a type of bullying, is linked to consistent fundamental personality traits of both the abuser and the survivor (Aquino & Thau, 2009).

Bullying can lead to a range of negative impacts on the victim, including social isolation, depression, psychosomatic illnesses, social maladjustment, anger, anxiety, and helplessness (Leymann, 1990). Bullying can manifest in derogatory actions, ignoring, slander, humor, contempt, or belittling of the target (Vartia, 2001). According to a study by Einarsen et al. (1994), common negative behaviors against the target include social alienation, ostracization, snarky criticism on their job, and verbal insults (Harvey et al., 2018). Thomas (2005) found that causing work pressure, demeaning one's skills, disrespecting them, and withholding knowledge were the top four methods of workplace bullying. Cyberbullying, a technological form of bullying, has emerged with the proliferation of electronic communication channels. Bullies can harm their targets by sharing harmful messages or media online, creating a new social problem in the workplace.

Bullying in the workplace can lead to a range of negative impacts on the victim, including social isolation, depression, and anxiety, which can ultimately affect the quality of customer service provided. Studies have shown that bullying can manifest in derogatory actions, such as belittling, ignoring, or slander of the target. Common negative behaviors against the target include social alienation, ostracization, and verbal insults. Moreover, bullying can create work pressure and demotivate employees, leading to decreased job satisfaction and ultimately, a decrease in the quality of customer service provided.

Cyberbullying has also emerged as a new form of workplace bullying, where bullies can harm their targets by sharing harmful messages or media online. Cyberbullying can further exacerbate the negative impacts of workplace bullying and create a new social problem in the workplace. Therefore, it is essential for organizations to take proactive steps to prevent bullying in the workplace, create a positive work environment that promotes employee engagement, and motivation to provide high-quality customer service.

Theoretical Background

According to Tran and Von Korflesch (2016), personality traits play a significant role in determining the behavior of an individual. The relationship between personality antecedents and workplace bullying is still uncertain, with some research suggesting that personality traits can explain exposure to bullying, while others argue that role conflict is a more significant factor (Balducci, Cecchin, & Fraccaroli, 2012). Previous studies have shown a link between personality traits and exposure to workplace bullying (Bamberger and Bacharach, 2006; Bowling et al., 2010; Milam et al., 2009), but findings have been inconsistent regarding differentiation between victims and non-victims of bullying based on personality traits (Coyne et al., 2000; Lind et al., 2009). The association between the Big Five personality traits and bullying has been explored in prior research (Bowling et al., 2010; Milam et al., 2009), but results have been mixed (Rammsayer et al., 2006; Lind et al., 2009; Glaso et al., 2009), leaving the relationship between personality characteristics and bullying unclear. Most workplace bullying research has been conducted in Western contexts with little attention paid to the Indian context, where there is a lack of evidence on the topic (D’Cruz and Noronha, 2010). This study aims to investigate the personality antecedents of bullying among automobile workers in India, where workplace bullying has emerged as a significant problem due to the unique features of the industry environment, including subjective performance evaluation and competing goals (Meyer, 2002). The study aims to evaluate the consequences of workplace bullying among automobile workers in India. (Podsiadly, Andrzej & Gamian-Wilk, Malgorzata. 2016; Tran and Von Korflesch, 2016; Zapf & Einarsen, 1999).

Workplace bullying is a pervasive problem that can have significant negative consequences for both individuals and organizations. It can result in decreased job satisfaction, increased stress and anxiety, decreased productivity, and higher turnover rates. It can also lead to legal action and damage the reputation of organizations. Due to its negative impact, it is important to understand the antecedents of workplace bullying and develop strategies to prevent it.

Personality traits have been identified as one potential antecedent of workplace bullying. The Big Five personality traits - openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism - have been found to be related to workplace bullying in some studies (Bowling et al., 2010; Milam et al., 2009), but not in others (Rammsayer et al., 2006; Lind et al., 2009; Glaso et al., 2009). This inconsistency may be due to the complexity of the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying, as well as the potential influence of contextual factors such as national and organizational culture.

In the Indian context, workplace bullying has received scant attention in academic research, despite the prevalence of the problem in the Indian workforce (D’Cruz and Noronha, 2010). This study aims to address this gap in the literature by investigating the personality antecedents of workplace bullying among automobile industry.

The consequences of workplace bullying in the automobile industry can be severe, leading to frustration, harassment, and a lack of equity among employees. It can also result in the loss of high potential workers, making it challenging for companies to maintain optimal performance levels. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the predictors of workplace bullying and implement strategies to prevent it.

This study aims to evaluate the consequences of workplace bullying among automobile industry workers in India. By examining the impact of workplace bullying on employees in this specific industry, the study can provide valuable insights into the unique challenges and consequences of bullying in the automobile industry. This knowledge can help organizations in the industry develop effective anti-bullying strategies to create a safer and more supportive work environment for all employee.

According to a recent study by Li and Liang (2021), workplace bullying can have negative consequences for the customer experience. The study found that employees who experience bullying are more likely to be less engaged, less motivated, and less willing to provide high-quality customer service. These findings are supported by previous research, including a study by Rodríguez-Muñoz, Baquero, and Rodríguez-Muñoz (2020), which found that workplace bullying can lead to decreased job satisfaction and a decrease in the quality of customer service provided.

Furthermore, studies have shown that bullying can create a toxic work environment that negatively affects the customer experience. For instance, a study by Liu, Wu, and Zhu (2021) found that workplace bullying can result in decreased customer satisfaction, loyalty, and ultimately harm the business's reputation. Customers may perceive negative energy and tensions among employees, leading to negative perceptions of the company

These studies highlight the importance of addressing workplace bullying to prevent negative impacts on both employees and customers. Organizations must prioritize creating a positive work environment that promotes employee engagement, motivation, and job satisfaction, leading to high-quality customer service and enhanced customer experience.

Overall, workplace bullying is a significant problem that can have negative consequences for individuals and organizations. Understanding the antecedents of workplace bullying, such as personality traits, is important for developing effective prevention strategies. This study aims to contribute to this effort by investigating the personality antecedents of workplace bullying among automobile workers in India and evaluating its consequences.

Hypotheses Development

This study utilizes trait theory (Costa & McCrae, 1992) to examine the personality antecedents of workplace bullying. Traits are relatively stable characteristics that shape an individual's responses to specific situations. Personality traits vary among individuals, influencing their perceptions, attributions for the causes of events, emotional reactions, and coping mechanisms in relation to anti-social impulses in the workplace (Spector, 2010). The Big Five personality dimensions provide a general taxonomy of personality, including openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, and are often used as an integrative approach to understanding personality in a common framework (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Five-Factor Model of Personality and Workplace Bullying

The Five-Factor Model (FFM) is a widely recognized model of personality traits that comprehensively covers the aspects of cultures and disciplines that matter to many employers. The FFM was established to identify the fundamental dimensions related to personality in order to categorize differences found in individuals, such as interpersonal, motivational, and emotional styles (McCrae & John, 1992). The FFM includes agreeableness versus dissension, extraversion versus introversion, conscientiousness versus lack of vision, neuroticism versus emotional soundness, and openness to experience versus restricting oneself to experience. Extraversion reflects the degree to which a person is social, gregarious, interactive, and outgoing. Individuals who are extroverted draw energy from interacting with others and generally perceive life events more positively, resulting in them not necessarily perceiving that workplace bullying has occurred (Milam et al., 2009). In contrast, introverts are often more sensitive and attentive to bullying behaviors. However, those with extreme introversion may struggle to establish effective communication with others, resulting in frustration and potentially feeling bullied by others (e.g., Digman, 1990). This can result in elevated levels of inter-role conflict, which may increase the likelihood of exposure to bullying in the workplace (Skogstad et al., 2007).

Conscientiousness is characterized by dutifulness, dependability, self-discipline, being ordered, and the need for achievement (Digman, 1990). However, employees who do not show consistency in their performance or who fail to demonstrate set performance standards may subsequently be closely monitored by their supervisor, triggering feelings of being bullied (Nielsen & Einarsen, 2015). Agreeableness refers to the extent to which an individual is trusting, helpful, and well-tempered. Studies have found a negative correlation between agreeableness and workplace bullying (Milam et al., 2009; Tepper, Duffy, & Shaw, 2001). Individuals with low agreeableness scores may perceive social interactions as annoying or even as bullying, resulting in their behavior being more likely to provoke others and increased risk of being bullied by others (Milam et al., 2009).

Openness is a personality trait that reflects a flexible, unconventional, autonomous, nonconforming, imaginative, and intellectually curious nature (Watson & Hubbard, 1996), as well as a willingness to explore original ideas (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Individuals with high levels of openness are generally more proactive and receptive to change, and less controlling and abusive (Kiazad et al., 2010; McCrae & Sutin, 2009). However, most findings suggest that openness is not related to experiences of workplace bullying (Bamberger & Bacharach, 2006; Glasø et al., 2007; Lind et al., 2009) because individuals scoring high on this trait tend to be more tolerant and flexible in the face of imperfections and stressful situations (Watson & Hubbard, 1996) compared to those with low scores (Smith & Williams, 1992).

Nevertheless, some past studies have suggested a modest association between openness and exposure to workplace bullying (Bowling et al., 2010):

H1: There is a negative correlation between workplace bullying and the Big Five personality traits of extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness among automobile workers. On the other hand, a positive correlation is expected between workplace bullying and the personality trait of neuroticism.

Consequences of Workplace Bullying

Workplace bullying can have significant negative impacts on both employees and organizations, ultimately leading to negative customer experiences. The behaviors associated with workplace bullying may include social exclusion, repeated humiliation, and verbal hostility, which can create a toxic work environment that negatively affects the quality of customer service provided (Einarsen et al., 2011). Prolonged conflicts can lead to bullying behaviors, producing counterproductive behaviors within the group, leading to neglect and decreased reciprocity, affecting teamwork and work outcomes (Fox & Spector, 1999). Exposure to workplace bullying has been found to instigate turnover intentions, which have negative effects on affective well-being and can lead to negative customer experiences (Razzaghian & Ghani, 2014).

Studies have found that workplace bullying has significant psychological and organizational costs for both employees and organizations, including decreased performance, increased healthcare costs, and increased turnover (Rai & Agarwal, 2018; Kivimaki et al., 2003; Namie, 2007). Victims of workplace bullying may experience reduced job satisfaction, intention to leave, and turnover intentions, leading to decreased motivation and ultimately affecting the quality of customer service provided (Djurkovic et al., 2008). Therefore, it is essential for organizations to take proactive steps to prevent bullying in the workplace, create a positive work environment that promotes employee engagement and motivation to provide high-quality customer service, ultimately enhancing the customer experience. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Workplace bullying is expected to have a significant impact on employees' intention to leave the organization and negative customer experience, with a positive correlation between the intensity of bullying experience and intention to leave, and a negative correlation between the intensity of bullying experience and customer experience.

Methods and Material

Sample

Participants in this survey were from Automobile Showroom of India. The questionnaire used in this survey was prepared in English and distributed among 1150 automobile across all levels in the organization. A total of 402 respondents returned useable questionnaires, representing a response rate of approximately 34%.

Scale used

The assessment in this study included several aspects besides the socio-demographic profile of participants, such as personality traits, workplace bullying experience, intention to leave, work performance, and work stress. All responses were collected using a five-point scale (1=never to 5=always) and detailed in the Appendix. Personality traits were evaluated using a 20-item scale by Domnellan et al. (2006), which consisted of five dimensions, including extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness, with four questions for each dimension. Workplace bullying was measured using the Negative Acts Questionnaire (revised version) (NAQ-R) developed by Einarsen and Hoel (2001), consisting of 22 items. Intention to leave was measured using a 10-item scale by Flinkman et al. (2010), with items such as “I am thinking about leaving this organization”. Customer Experience was evaluated through Net Promoter Score (NPS). The NPS is a widely used metric that measures customer loyalty and satisfaction by asking customers how likely they are to recommend a product or service to others. The scale ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 being the lowest score and 10 being the highest.”

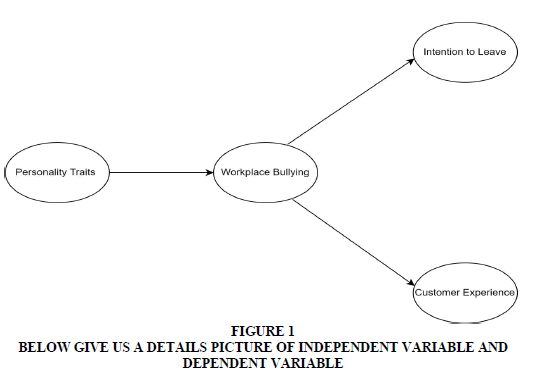

Variables

Automobile workers who score high in extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness are likely to encounter less workplace bullying, while those who score high in neuroticism are more prone to workplace bullying. The level of workplace bullying that automobile workers encounter is likely to lead to an increase in the intention to leave and a decrease in work performance. In this context, workplace bullying serves as an independent variable Figure 1.

Repercussions of Work Place Bullying

1- Intention to Leave (Dependent Variable)

2- Customer Experience (Dependent Variable)

Proposed Conceptual Model

Results Analysis and Discussions

The study utilized a questionnaire to assess various variables among participants. The Big Five Personality Traits, including Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Neuroticism, and Openness, were measured using a 4-item scale each. The retained mean score for Extraversion was 4.13 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.753, for Conscientiousness was 4.194 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.714, for Agreeableness was 4.348 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.754, for Neuroticism was 4.265 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.676, and for Openness was 4.201 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.750. The personality variable, which included all the Big Five Personality Traits, had a retained mean score of 4.227 with a high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.917, indicating good internal consistency. Individual-level workplace bullying was measured using the Negative Acts Questionnaire (revised version) (NAQ-R), which had 22 items. The retained mean score for NAQ was 1.755 with a high Cronbach’s alpha of 0.924, indicating good internal consistency.

Customer Experiencewas measured using a 7-item scale, and the retained mean score was 3.956 with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.806. Overall, the study utilized reliable and valid measures to assess the Big Five Personality Traits, individual-level workplace bullying, intention to leave, and Customer Experienceamong participants (Nunnally,1967) represents the respondents’ profiles in terms of gender, age, experience, hours worked per week, number of employees, marital status, and qualifications. Male and female automobile sector respondents were almost equal in numbers. The participants had a PhD, postgraduate, and undergraduate degree. More females had Ph.D. degrees compared to male automobile industry members. However, more male members had post graduate qualifications than female workers. Only a few participants were under graduates. The married respondents’ percentage was higher for males than females. Working hours for male respondents were slightly higher, with similar standard deviation, compared to female respondents.

It displays the descriptive statistics of various variables for male and female participants. The mean age of male participants was 38.86 years (SD = 8.335), which was slightly higher than the mean age of female participants, 37.21 years (SD = 8.499). On average, male participants reported having more work experience (M = 9.11, SD = 7.937) compared to female participants (M = 7.90, SD = 7.795). Male participants also reported working longer hours per week (M = 39.98, SD = 12.363) compared to female participants (M = 36.83, SD = 12.541). In terms of the number of employees, there were 196 (49.12%) male participants and 203 (50.87%) female participants. The majority of both male (78.06%) and female (71.92%) participants reported being married. In terms of qualifications, male participants reported higher levels of PhD (44.82%) and undergraduate (44.82%) qualifications compared to female participants (46.94% and 46.94%, respectively). Overall, these results suggest some differences in demographics and qualifications between male and female participants.

Results

According to all personality dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness) exhibited a strong negative correlation with workplace bullying, with correlations ranging from -0.813 to -0.858 (p<0.01). Workplace bullying also demonstrated a significant negative correlation with Customer Experience(r=-0.254, p<0.01) and a strong positive correlation with intention to leave (r=0.807, p<0.01). Additionally, the personality dimensions were found to have negative correlations with intention to leave (extraversion r=-0.747, agreeableness...) r=–0.764, conscientiousness r=–0.746, neuroticism r=–0.710, and openness r=–0.810; p<0.01).

The correlations were in the hypothesized direction except in the case of neuroticism that was negatively associated with workplace bullying.

Notes: ZTE=extraversion; ZTA=agreeableness; ZTC=conscientiousness; ZTN=neuroticism; ZTO=openness; ZWP=customer experience; ZNAQ=workplace bullying; ZTI=intention to leave.

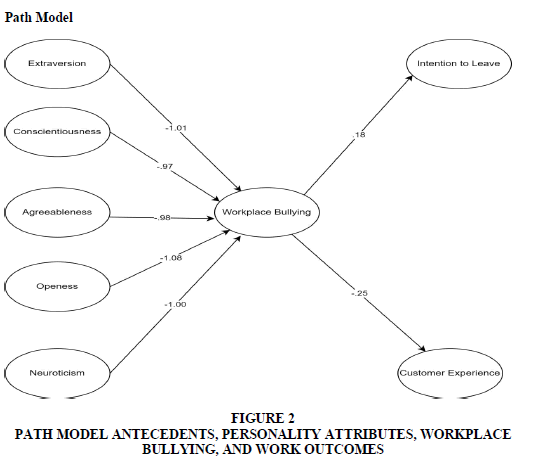

In this study, the researchers utilized structural equation modelling (SEM) to investigate the hypotheses and examine the causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The AMOS 21.0 software was used to test the path analysis of the hypotheses presented in Figure 2. The beta coefficient in multiple regressions was equivalent to the path coefficient used in the analysis. The results supported the first hypothesis, indicating that an increase in extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness was associated with a decrease in workplace bullying. Interestingly, the study found that neuroticism was also negatively correlated with workplace bullying, contrary to popular belief. Furthermore, the results supported the second hypothesis, revealing that automobile workers experiencing higher levels of workplace bullying had increased intention to leave and decreased work performance.

The study used Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to investigate the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying, as well as the impact of workplace bullying on intention to leave and work performance. The results revealed that higher levels of extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness were significantly associated with lower levels of workplace bullying. However, contrary to expectations, neuroticism was not significantly associated with workplace bullying. In addition, the results supported the hypothesis that workplace bullying is negatively associated with work performance, as evidenced by a significant negative path coefficient. Workplace bullying was also found to have a positive association with intention to leave, indicating that employees who experience higher levels of bullying are more likely to want to leave their organization.

These findings highlight the importance of considering personality traits when assessing workplace bullying and its impact on employee outcomes. The study suggests that organizations should focus on fostering a positive work environment and addressing workplace bullying to improve employee well-being and customer experience.

Measures of Model Fit:

The model was analyzed using the raw data via Amos relevant fit indexes, along with the standardized output.

The final model's fit was evaluated using various fit indices, including the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), X2/DF, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The GFI was 0.982, which is above the recommended cutoff value of 0.90, indicating a good fit. The X2/DF was 2.518, which is below the recommended cutoff value of 3.00, also indicating a good fit. The CFI and IFI were both 0.995, exceeding the recommended cutoff value of 0.90, further indicating a good fit. The AGFI was 0.943, which exceeded the recommended cutoff value of 0.80, indicating an acceptable fit. Lastly, the RMSEA was 0.062, which was below the recommended cutoff value of 0.08, suggesting a good fit for the final model. Overall, the various fit indices suggest that the final model fit the data well presents the fitness measures of the path model, where chi-squares were found to be significant (p<0.001). As chi-square is sensitive to sample size, the relative chi-square was estimated. The relative chi-square was less than 3, indicating a good fit of the model. Other measures of fitness, including GFI, CFI, and NFI, were above 0.90, indicating a good fit of the model. The parsimonious fit measures (PGFI, PCFI, and PNFI) were within acceptable limits in the models. RMSEA, a parsimony-adjusted index, showed a lower value, indicating a better model fit. According to Browne & Cudeck (1993), an RMSEA value below 0.5 is the best indicator of model fit. Steiger (1990) suggested that the RMSEA value should be less than 0.10, while MacCallum et al. (1996) suggested that values below 0.08 are considered a good fit. In this study, RMSEA values were ≤0.08, indicating an acceptable model fit.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the personality antecedents and consequences of workplace bullying among 402 Automobile Showroom workers in India using a cross-sectional design. The study used structural equation modeling to test the hypothesized relationships between the antecedents and consequences of workplace bullying. The results showed a robust relationship between the antecedents and consequences of workplace bullying, as reflected by the high coefficient magnitudes of structural paths/constructs and the statistical significance level of the p-value. Among all personality traits, neuroticism had the highest path coefficient for workplace bullying, which means that automobile workers who are more likely to be bullied had higher neurotic tendencies such as moodiness and experiencing unwanted feelings. This finding supports the previous research that neuroticism has a negative association with bullying. On the other hand, openness was found to have a negative association with workplace bullying, meaning that more open automobile worker experienced less bullying.

This study aimed to investigate the personality traits that contribute to customer service representatives being subjected to workplace bullying and how it impacts the customer experience. By understanding the link between personality traits and workplace bullying, organizations can take steps to prevent customer service representatives from experiencing bullying and ensure that customers receive high-quality service.

The study also found a positive association between workplace bullying and intention to leave, supporting previous findings. The results suggest that understanding the Big Five personality characteristics can play an important role in reducing workplace bullying. Organizations can use personality testing to identify likely victims of bullying and initiate anti-victimization efforts to safeguard such individuals. Additionally, building leadership and framing policies focusing on reducing incivility and appropriate training, assessment, and continuous observation can help organizations control bullying. Future research can be conducted on other existing personality models, such as Eysenck's three-factor model, and on cyberbullying, which is a new social problem in work the workplace. Overall, the study highlights the importance of understanding personality traits in preventing and addressing workplace bullying.

References

Aquino, K., & Thau, S. (2009). Workplace victimization: Aggression from the target's perspective. Annual review of psychology, 60, 717-741.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Balducci, C., Cecchin, M., & Fraccaroli, F. (2012). The impact of role stressors on workplace bullying in both victims and perpetrators, controlling for personal vulnerability factors: A longitudinal analysis. Work & Stress, 26(3), 195-212.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bamberger, P.A., & Bacharach, S.B. (2006). Abusive supervision and subordinate problem drinking: Taking resistance, stress and subordinate personality into account. Human Relations, 59(6), 723-752.

Brown, M. W. & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sage Publication, International Educational and Professional Publisher, Newbury Park, London, New Delhi.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R., R. (1987). Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81-90.

Coyne, I., Seigne, E., & Randall, P. (2000). Predicting workplace victim status from personality. European journal of work and organizational psychology, 9(3), 335-349.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Einarsen, S. (2001). The Negative Acts Questionnaire: Development, validation and revision of a measure of bullying at work. In Proceedings of the 10th European Congress on Work and Organisational Psychology, Prague, May 2001.

Einarsen, S., &Hoel, H. (2001) The Negative Acts Questionnaire: Development, validation and revision of a measure of bullying at work. Paper presented at the 10th. European Congress on Work and Organisational Psychology, Prague.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D. & Cooper, L. C. (2003). Maltreatment and emotional abuse in the workplace: international perspectives in research and practice. London: Taylor & Francis (Eds.)

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2011). The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace (pp. 3–40). London: Taylor & Francis.

Einarsen, S., Raknes, B. I., & Matthiesen, S. B. (1994). Bullying and harassment at work and their relationships to work environment quality: An exploratory study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 4(4), 381–401. Education

Fox, S., & Spector, P.E. (1999). A model of work frustration–aggression. Journal of organizational behavior, 20(6), 915-931.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harvey, M., Moeller, M., Kiessling, T., & Dabic, M. (2018). Ostracism in the workplace. Organizational Dynamics.

John, O.P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives.

Kivimäki, M., Virtanen, M., Vartia, M., Elovainio, M., Vahtera, J., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2003). Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occupational and environmental medicine, 60(10), 779-783.

Leymann, H. (1990). Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence and victims, 5(2), 119-126.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European journal of work and organizational psychology, 5(2), 165-184.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, L., & Liang, J. (2021). Exploring the influence of workplace bullying on customer-directed employees’ service sabotage behavior: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102856.

Lind, K., Glasø, L., Pallesen, S., & Einarsen, S. (2009). Personality profiles among targets and nontargets of workplace bullying. European Psychologist, 14(3), 231-237.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Milam, A.C., Spitzmueller, C., & Penney, L.M. (2009). Investigating individual differences among targets of workplace incivility. Journal of occupational health psychology, 14(1), 58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morten Birkeland Nielsen, Lars Glasø, Ståle Einarsen (2017), Exposure to workplace harassment and the Five Factor Model of personality: A meta-analysis, Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 104, Pages 195-206, ISSN 0191-8869.

N.A. Bowling, T.A. Beehr, M.M. Bennett, C.P. Watson Target personality and workplace victimization: A prospective analysis Work and Stress, 24 (2) (2010), pp. 140-158

Namie, G. (2007). The challenge of workplace bullying. Employment Relations Today, 34(2), 43.

Nielsen, M.B., Tangen, T., Idsoe, T., Matthiesen, S. B., & Magerøy, N. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder as a consequence of bullying at work and at school. A literature review and meta-analysis. Aggression and violent behavior, 21, 17-24.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nunnally, Jum C. (1967), Psychometric Theory, 1 st ed., New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ongori, H., & Agolla, J.E. (2008). Occupational stress in organizations and its effects on organizational performance. Journal of management research, 8(3), 123-135.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Podsiadly, A., & Gamian-Wilk, M. (2017). Personality traits as predictors or outcomes of being exposed to bullying in the workplace. Personality and Individual Differences, 115, 43-49.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Skogstad, A., Einarsen, S., Torsheim, T., Aasland, M.S., & Hetland, H. (2007). The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. Journal of occupational health psychology, 12(1), 80.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Smith, T.W., & Williams, P.G. (1992). Personality and health: Advantages and limitations of the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 395-425.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spector, P.E. (2011). The relationship of personality to counterproductive work behavior (CWB): An integration of perspectives. Human resource management review, 21(4), 342-352.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Steiger, J.H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate behavioral research, 25(2), 173-180.

Tepper, B.J., Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Personality moderators of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates' resistance. Journal of applied psychology, 86(5), 974.

Thomas, M. (2005). Bullying among support staff in a higher education institution. Health Education.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tran, A.T., & Von Korflesch, H. (2016). A conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention based on the social cognitive career theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vartia, M.A. (2001). Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 63-69.

Watson, D., & Hubbard, B. (1996). Adaptational style and dispositional structure: Coping in the context of the Five-Factor model. Journal of personality, 64(4), 737-774.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zapf, D. (1999). Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International journal of manpower.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 10-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13470; Editor assigned: 11-Mar-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13470(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Mar-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13470; Revised: 16-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13470(R); Published: 01-Aug-2023