Research Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 1

"Tourist' Sense of Place", an Assessment of the Sense of Place in Tourism Studies: The Case of Portugal

Frederico D’Órey, University Portucalense (UP)

António Cardoso, University Fernando Pessoa (UFP)

Ricardo Abreu, Lisbon University Institute (ISCTE-IUL)

Abstract

The Sense of Place has been addressed in tourism studies as an object of concern to academics and policymakers. From mass tourism to personalized travel, understand the relationship between tourists and places it’s an effort to improve the tourism sustainability. This article proposes to explore the perception of tourists in Portugal by modelling the Sense of Place dimensions. This approach introduces the holistic multidimensional concept of Sense of Place as a relationship between the tourists and the places they visit. Data from 500 surveys were subjected to Factor Analysis that confirmed four factors or dimensions of tourist’s perception. This research has also found that some sociodemographic variables have a significant effect on tourist’s Sense of Place. Tourism is a prominent subject area in marketing studies and this article brought to the discussion, a multivariate methodology to modelling individual perceptions of places. This method allowed us to identify a set of tourist profiles associated with these Sense of Place dimensions. Resulting in relevant outputs for the brand tourism management and destinations strategic planning.

Keywords

Sense of Place, Tourist Destinations, Commitment to a Place, Identification with a Place.

Introduction

In today’s globalized world, we are confronted by the widespread expansion of mass tourist activities which have heavy impacts on the most sought-after destinations and the societies that contain them. The purpose of marketing in tourist destinations takes the specific forms of, primarily, marketing places and, secondly, applying the other skills of professionals in tourism marketing.

Tourism marketing identifies the tourists’ destinations as “places” in which individuals, as tourists, realize their expectations and enjoy their leisure experiences. This approach implies that the tourist destination is the place where tourist activities happen, though tourist destinations are not necessarily geographical “places”, nor are the geographical places primordially “tourist destinations” (D’Orey, 2014).

Two complementary perspectives can be found in tourism marketing: the marketing of places and the marketing of destination. The first aims at the development of the brand, the creation of wealth, the sustainability and competitiveness of the regions or localities (i.e. places) (Anholt, 2006; Dhamija et al., 2011; Muñiz-Martinez, 2012; Rizzi & Dioli, 2010; Smith, 2015). In the second, the focus is broader and falls on infrastructures and the capacities of the destinations to welcome the tourist activity, a socio-economic vision of the places (Pike, 2015; Wang & Pizam, 2011; Witt & Moutinho, 1994).

In the last resort, the function of tourism marketing is to transform a certain place into a pole of tourist attraction, with the development of products and specific services at the same time, which confers on that tourist offer psychological properties of the place itself. But, naturally, tourist destinations do not possess the psychological properties of the places (Devine-Wright & Clayton, 2010; Smith, 2015; Counted, 2016; Acedo et al., 2017).

For tourism marketing to shelter this complementary double function of transforming a geographical locality into a tourist destination, it is necessary to understand the relationship between people and places. One way to explain this relationship is to take account of the phenomenon of “Sense of Place”, or, in other words, the psychological perceptions emerging from the expectations and experiences of the individuals in their tourism leisure activity (Campelo et al., 2013; Roult et al., 2016; Clarke et al., 2018, Poljanec-Bori? et al., 2018; Jarratt et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2018; Azizi, 2018)

On this point it makes sense to ask how this “Sense of Place” (Smith, 2015) is developed in individuals and what its effect is on the profile of tourists. For this purpose, this article draws on the construction of tourist places (D’Orey, 2014:2015, Poljanec-Bori? et al., 2018) and outlines the most significant socio-demographic profile of the non-resident tourists, considering their overall perception of the “Sense of Place”.

Review Of The Literature

When reflecting on “Tourist Destinations”, we are led to consider the existence of the concept of ‘Place’, where the tourists’ lived experiences happen and their activities produce effects. This relationship between individuals and places leads us to interpret it as the behaviour and attitudes of tourists in relation to the places they visit. In fact, various studies suggest that the “Sense of Place” is a holistic dimension that best explains the relationship between people and places (Campelo et al., 2013; Lin & Lockwood, 2014; Counted, 2016; Smith, 2015; Roult et al., 2016; Clarke et al., 2018; Acedo et al., 2017; Poljanec- Bori? et al., 2018; Jarratt et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2018; Azizi, 2018).

The origin of the concept of “Sense of Place” goes back to the 1970s, in the field of human geography, particularly in the fruitful work of Yi-Fu Tuan (1974, 1977, and 1979). For Tuan, “Place” is a symbiotic relationship between “space” and the “meanings” for individuals. It is as if we were dealing with dialectic in which human experience in “spaces” is reproduced “in the basic components of the living world” (Tuan, 1977). In other words, the human being understands his or her environment through experiences in interaction with places.

This interaction is full of defined “meanings”, by the nature and culture of the spaces, whether individually or by both simultaneously, and interpreted by human experiences, their relationships, emotions and thoughts (Stedman et al., 2004). In an integrated way, Richard Stedman (2003) suggests that the “Sense of Place” comes from four fundamental elements of individual experience with places: the characteristics of the environment; the interactions and behaviour of the individuals in relation to their surroundings; the meanings as social construction of experience with the attributes of the physical spaces; and perceptions as affection, satisfaction or identity in relation to the surrounding spaces.

The Sense of Place can be the vehicle for the comprehension of the attitudes of individuals concerning their environment (Smith, 2015; Azizi, 2018). In it are to be found functional and cognitive components that mould the perceptions, beliefs, values and commitments of individuals (Larson et al., 2013; Lin & Lockwood, 2014), that make the Sense of Place a privileged area for analysing the behaviour of tourists and travelers (Deutsch et al., 2013; Azizi, 2018; Poljanec-Bori? et al., 2018).

Behaviour arises from the specific experiences of individuals, independently of the size of the places they visit, whether town, region or even a whole country. And they reproduce positive feelings, such as well-being and safety, or negative feelings, such as fear or placelessness. These emotional connections that structure the Sense of Place amount to a description of the unique characteristics of the places (Foote & Azaryahu, 2009; Jarratt et al., 2018).

The more physical elements, the activities and the meanings of the places are interlaced in the daily experiences of individuals in a unique symbiosis that distinguishes each tourist destination from the many others (Shamsuddin & Ujang, 2008; Azizi, 2018; Tan et al., 2018). It may be affirmed that the Sense of Place is a multidimensional construction that represents beliefs, emotions and understandings with a definite location that translates into the identity of that place (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2006).

The Sense of Place aggregates in itself a multidimensional and complex perception in which each place transmits to the individuals’ specific values and symbols. Various studies point to the Sense of Place as a complex concept associated with the emotions and behaviour of individuals in relation to the places which can be interpreted in terms of levels of perception (Kaltenborn, 1998; Relph, 1976; Shamai, 1991; Shamai & Ilatov, 2005; Campelo et al., 2013; Azizi, 2018; Tan et al., 2018).

Shamai (1991) classifies the relationship of individuals with a place on a scale of increasing intensity, from absence of sense of place to sacrifice for the place. In his methodology, the author utilizes a qualitative approach based on questionnaires put to students of a religious school in the Province de Ontário, Canada. Kaltenborn (1998) takes up Shamai’s scale, structuring it on three levels of intensity: “Belonging to a Place”; “Affection for a Place”; “Commitment to a Place”; and “Identification with a Place”.

The sense of belonging to a place arises when the individuals have a continuing relationship of positive thoughts about a certain place (Vorkinn & Riese, 2001). Chang (1997) mentions that ‘Belonging to a Place’ depends on the different values and intentions of individuals in respect to those places. The author goes along with Relph (1976), who suggests that tourists can demonstrate some degree of introspection and of exteriority, which is an ambiguous sense of belonging to the place.

Affection for a place involves emotions, beliefs, values and symbols that individuals or groups possess in relation to a locality. George & George (2012) observe that affection for a place is a determining factor in the construction of fidelity to destinations, suggesting two dimensions of affect: one more functional (i.e. dependency on the place) and the other of a more emotional character (i.e. identity of the place). Both provide explanations for the fidelity of tourists to a place.

Yuksel et al. (2010), refer to the role of affection for a place in the construction of future satisfaction and behaviour. They state that tourists develop certain affection for a place as a result of its ability to reach specific objectives or provide suitable activities in the locations visited. The authors suggest that affection for the place is a determining factor for prediction of intentions and behaviour showing fidelity to a destination.

Commitment to a place is positioned on Shamai’s (1991) scale on the point of ‘sacrifice for the place’; that is, at the extreme of the relationship of the individual to the place. For other authors (Smaldone et al., 2005), commitment to a place is the level at which people are ready to take action to protect the place.

The concept de “Identity with the Place”, was put forward by Proshansky (1978), who described it as an idea of place in a broader concept of the very existence of the individual; that is, “place” goes from being an abstract concept to making part of the definition of the individual himself or herself and of his or her personality. Identity with place is thus considered by the authors to be a characteristic of the self, like gender or social class that is learnt from the existing environment. They are a mixture of specific feelings about the physical and symbolic aspects of places that define the individual (Proshansky et al., 1983).

The theoretical table shows us various dimensions exogenous to the “Sense of Place” concept. They are dimensions formulated from the starting point of the relations between individuals and places, which, in a certain way, project the perceptions of “Belonging to a Place”, “Affection for a Place”, “Commitment to a Place” and “Identification with a Place” (Table 1).

| Table 1 Principal concepts concerning the perception of ‘sense of place’ |

|

| Concepts | References |

| Belonging to Place | (Chang, 1997; Kaltenborn, 1998; Relph, 1976; Vorkinn & Riese, 2001) |

| Affection for a Place | (George & George, 2012; R. Stedman et al., 2004; R. C. Stedman, 2003; Yuksel et al., 2010) |

| Commitment to a Place | (Shamai, 1991; Shamai & Ilatov, 2005; Smaldone et al., 2005) |

| Identification with a Place | (Proshansky, 1978; Proshansky et al., 1983) |

In the Bibliography we find empirical data that demonstrates the existence of contiguous dimensions that formulate individuals’ perception of “Sense of Place”. However, most of the studies carried out until today are limit their empirical research to the native residents of a particular region or locality. This article addresses the concepts associated with “Sense of Place” from the perspective of non-resident tourists and develops a profile based on their sociodemographic characteristics and their individual attributes of perception.

Proposed Methodology

Using a questionnaire, we conducted a survey of 500 tourists in the international departure terminals of Lisbon International Airport. Lisbon Airport was chosen because of the large number of people using it and the heterogeneous nature of their destinations. Data collection was done by a team of five specialists near the international boarding gates by means of the Paper-and-Pencil Interviewing (PAPI) (Lavrakas, 2008). The diversity of passengers passing through the airport being very great, the researcher opted for the method of stratified sampling. Detailed data on the collection process and the instruments used are discussed in the studies by D’Orey (2015).

The questionnaire is made up of questions designed to capture the perceptions of the respondents on the Feeling of Place, developed in part in the studies carried out by Shamai (1991), Kaltenborn (1998) and Relph (1976), validated by a focus group of specialist stakeholders in the tourism sector. The questions were adapted in such a way as to focus the attention of the respondents on the notions “Belonging to a Place”, “Affection for a Place”, “Commitment to a Place” and “Identifying with a Place”. All the questions were answered on a Likert scale of 5 points from total disagreement to total agreement. Additionally, there were questions of a sociodemographic character and others eliciting outline information about each tourist’s stay in Portugal.

Following information provided by ANA Aeroportos SA and data from the Portuguese authorities (Turismo de Portugal & GFK, 2012), it was possible to construct a sample stratified by representative convenience from the profile of international tourist in Portugal. Data collection was done during a period of five days from 15th to 19th July 2017 and distributed among diverse international flights at the 44 boarding gates of the airport. Table 2 shows the profile of the sample.

| Table 2 Description Of The Sample |

|||

| Variable | Frequency | % | % Accumulated |

| Age | |||

| <15 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 15–25 | 102 | 20.4 | 20.6 |

| 25–65 | 376 | 75.2 | 95.8 |

| ≥ 65 | 21 | 4.2 | 100.0 |

| Education | |||

| Secondary education | 77 | 15.4 | 15.4 |

| Higher Education | 358 | 71.6 | 87.0 |

| Other | 65 | 13.0 | 100.0 |

| Profession | |||

| Employer | 68 | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| Employee | 335 | 67.0 | 80.6 |

| Retired | 24 | 4.8 | 85.4 |

| Student | 62 | 12.4 | 97.8 |

| Not Stated/No Response | 11 | 2.2 | 100.0 |

The questionnaire was directed at tourists on holiday, excluding the many involved in business tourism. According to Turismo de Portugal (2012), that profile of tourists is characterized as being mostly men aged from 35 to 44 years, of which 50% have university degrees and European nationalities. Table 3 shows the national origin of the tourists as well as the last country that they visited on holiday.

| Table 3 Designation Of The Country Of Origin And The Last Country Visited On Holiday |

|||

| Country | Frequency | % | % Accumulated |

| Nationality | |||

| France | 66 | 13.2 | 13.2 |

| Germany | 51 | 10.2 | 23.4 |

| Brazil | 51 | 10.2 | 33.6 |

| Spain | 42 | 8.4 | 42.0 |

| Russia | 26 | 5.2 | 47.2 |

| Belgium | 24 | 4.8 | 52.0 |

| The Netherlands | 24 | 4.8 | 56.8 |

| Italy | 21 | 4.2 | 61.0 |

| Others | 195 | 39.0 | 100.0 |

| Europe (28) | |||

| European | 307 | 61.4 | 61.4 |

| Non-European | 193 | 38.6 | 100.0 |

| Last country visited | |||

| Spain | 70 | 14.0 | 14.0 |

| France | 54 | 10.8 | 24.8 |

| Italy | 51 | 10.2 | 35.0 |

| Lisbon | 48 | 9.6 | 44.6 |

| Portugal | 41 | 8.2 | 52.8 |

| Others | 236 | 47.2 | 100.0 |

Recent studies of tourism in Portugal (Turismo de Portugal & GFK, 2012) indicate that most international tourists are accommodated in hotels, accompanied by their families and they stay more than four nights. The data from the sample reveal that Lisbon (48.2%), Algarve (16.2%), Porto (6.4%) and Madeira (6.2%), are the main regions or localities preferred by those surveyed during their stay. Table 4 shows the profile of those questioned about their stay.

| Table 4 Profile Of Those Questioned About Their Stay |

|||

| Profile | Frequency | % | % Accumulated |

| Duration of stay | |||

| 1-3 nights | 68 | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| 4 or more nights | 432 | 86.4 | 100.0 |

| Type of lodging | |||

| Hotel | 316 | 63.2 | 63.2 |

| Hostels | 16 | 3.2 | 66.4 |

| Holiday village | 18 | 3.6 | 70.0 |

| Others | 150 | 30.0 | 100.0 |

| Accompanied by family | |||

| Yes | 435 | 87.0 | 87.0 |

| No | 65 | 13.0 | 100.0 |

Results And Discussion

Analysis of the Data and Construction of the Conceptual Model of “Sense of Place”

The analysis of the sample follows an exploratory method with the objective of finding the subjacent dimensions of the Sense of Place. From the questionnaire, 12 questions were selected which relate to these dimensions and are subject to factorial analysis. In accordance with Malhotra (2012) the Factorial Analysis of Principal Components considers the total variance in the data, in the reduction and summarization of the initial data, simplifying its analysis.

For Harry Harmann (1976) Factorial Analysis consists of a linear combination of observed variables more correlated among them, forming new variables. This methodology makes it possible to diminish the complexity of this study and allows us to identify the most important dimensions of this analysis. For this article, we opt for an Exploratory Factorial Analysis by the extraction of the principal components, which enables us to find a set of facts that form a linear combination among the variables in the matrix of correlations (Malhotra, 2012).

According to Aaker et al. (2012), the factorial process can be evaluated by the Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin (KMO) índex, which reflects the measure of adequacy of the sample, and by Bartlett’s sphericity test, which shows us the significance of the degree of correlation between variables, the communalities that represents the proportion of variance explained by the common factors, it being possible to identify the useful variables for the exercise of this study and the eigenvalue that defines the variance explained by each factor.

With the help of IBM SPSS® software, we proceeded to the factorial extraction of the sample. From the visualization of the Scree Plot, it was determined that there were 4 principal factors that explained 71% of the variance of the observed variables (i.e. 12 questions). The Scree Plot is an alternative way of evaluating the eigenvalue of the factors, demonstrating their degree of importance by ordering them in descending order.

To guarantee the consistency of the factorial analysis, we proceeded to the Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin (KMO) test of the adequacy of the sample, which yielded the value of 0.883, and the Bartlett test of sphericity yielded a null value for the level of significance (p ≤ 0.05), allowing us to affirm that the reduced number of factors explains a great part of the variability of the data. The factors are characterized by the variables that demonstrate the greatest factorial weight in their component (≥ 0.05). The rotation of the matrix of factors permits greater clarity in the grouping of the variables under the factors (i.e. principal components). Table 5 shows the matrix of factors after the rotation and elimination of the variables with factorial weighs less than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013).

| Table 5 Matrix Of The Rotation Of Components |

||||

| Components (factors) | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| The events that occurred during my visit were important to me | 0.808 | |||

| My experiences in this place had a big effect on me | 0.73 | |||

| I’m thinking of leaving my country or city and going to live in this place | 0.909 | |||

| I recognize myself in the lifestyle of the people who live in this place | 0.592 | |||

| I’m ready to invest my time and talent to improve this place | 0.546 | |||

| This place has a lot to do with me | 0.467 | |||

| It would be a very good place to come back to for a holiday | 0.887 | |||

| I love this place and, if I could, I would spend more time in it. | 0.847 | |||

| To me, visiting this place isn't strange | 0.862 | |||

| I’m ready to dedicate myself body and soul to preserving the heritage of this place | 0.615 | |||

| After visiting this place, I feel that it’s part of me | 0.507 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.a | ||||

|

Note: a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations. |

||||

All the variables show communalities greater than 0.06, demonstrating their capacity to represent the factor in question; in other words, the proportion of variance that is explained by the common factors (Malhotra, 2012; Tucker et al., 1969). The first dimension (i.e. principal component 1) tries to explain the sense of belonging to a place by transmitting some traces of the behaviour of the tourist in respect to the place. It is characterized by two observed variables that explain 19.6% of the variance and demonstrate the importance of the places visited in the lives of the tourists.

The second dimension is made up of 4 observed variables that explain 18.6% of the variance, highlighting the variable (i.e. the statement) “I’m thinking of leaving my country/city and going to live in this place”, which registers the highest ‘loading’ of the four variables of the factor and demonstrates the level of commitment to the place that the tourist is disposed to have.

The third dimension is made up of two variables, also with elevated factorial loadings, that explain approximately 17.7% of the variance and are intended to represent the sense of affection for the place. The statement ‘I love this place and, if I could, I would spend more time here’ is very representative of the affection that tourists have for the place they have visited.

Finally, the fourth dimension is made up of variables that explain 15, 3% of the variance. The statements, “To me, visiting this place isn’t strange” and “After visiting this place, I feel that it is part of me” are revealing of the sentiment “identity with place”.

The factorial analysis reveals that the variables observed, have high weights of regression relative to their respective factors, shown in Table 6. “The affection for the place” is the factor that shows the greatest internal consistency in its factorial composition, demonstrating in a certain way the capacity of this factor to represent the “sense of place” by the emotional links of the individual with the place. In fact, the variable “I love this place and, if I could, I would spend more time here” reflects that connection with a factorial weight very close to the maximum limit of correlation.

| Table 6 Factorial Weighting Of The Indicators In The Factorial Model |

||

| Factors (variables) | Est.a | Alfab |

| Belonging to a Place | ||

| The events that occurred during my visit were important to me | 0.636 | |

| My experiences in this place had a big effect on me | 0.763 | 0.653 |

| Commitment to a Place | ||

| I’m thinking of leaving my country or city and going to live in this place | 0.560 | |

| I recognize myself in the lifestyle of the people who live in this place | 0.637 | |

| I’m ready to invest my time and talent to improve this place | 0.730 | 0.781 |

| This place has a lot to do with me | 0.786 | |

| Affection for a Place | ||

| It would be a very good place to come back to for a holiday | 0.702 | |

| I love this place and, if I could, I would spend more time in it. | 0.965 | 0.806 |

| Identification with a Place | ||

| To me, visiting this place isn't strange | 0.466 | |

| I’m ready to dedicate myself body and soul to preserving the heritage of this place |

0.658 | 0.689 |

| After visiting this place, I feel that it’s part of me | 0.837 | |

|

Note: a Standardized estimates of the factorial model; b Internal Consistency by Alfa de Cronbach |

||

The “Sense of Place” perceptions of the tourists surveyed show different degrees of intensity (Table 7). The tourists considered “Affection for a Place” the aspect of greatest importance (4.0), “Belonging to a Place” and “Identification with a Place” intermediate (3.4 e 3.5), while “Commitment to a Place”, they thought to be of least importance (2.9) relative to the remaining aspects. With the objective of identifying the influence of the tourist profile on the dimensions of the Feeling of Place, we carried out various regressions and tests of differences among these dependent variables, and some sociodemographic characteristics and details of the stay of the people questioned.

| Table 7 Descriptive Analysis Of The Dependent Variables |

|||||

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation | |

| Belonging to a Place | 488 | 1 | 5 | 3.4805 | 1.03736 |

| Commitment to a Place | 487 | 1 | 5 | 2.924 | 1.01917 |

| Affection for a Place | 499 | 1 | 5 | 4.0461 | 1.0499 |

| Identification with a Place | 489 | 1 | 5 | 3.5331 | 1.03924 |

| N valid (listwise) | 471 | ||||

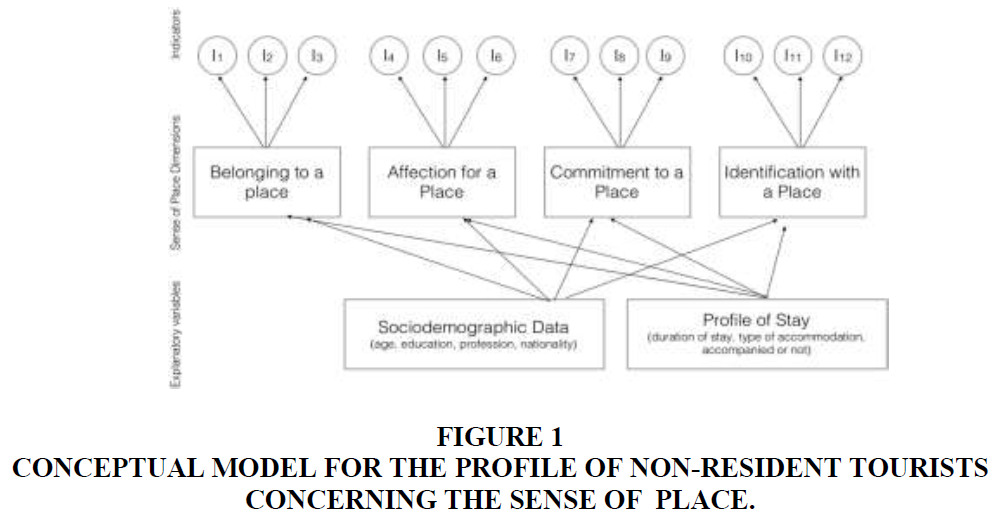

In short, the factorial model of Sense of Place put forward, identified in the exploratory study and represented by four factors or principal components, shows variables with a high degree of internal consistency and a strong relationship with its indicators. With the objective of evaluating the profile of the tourists, we proceeded to the construction of interpretative models of the relationships among these dimensions of the Sense of Place and the sociodemographic factors (Figure 1).

The Sense Of Place In Non-Resident Tourists

To analyze the profile of the tourists in the proposed model of “Sense of Place”, the “Factor Scores” were estimated as dependent variables in the respective regression models, using IBM SPSS® software. The scores were estimated by the Thompson method (regression method), which utilizes estimated values of the factorial weightings and of singularities as if they were populational values (Johnson & Wichern, 2002; Marôco, 2010).

Regression models were applied to the four variables of the sociodemographic data and three variables considered to profile the stay of the tourists questioned. Table 9 shows the values of the coefficients of regression (i.e. non-standardized coefficients ‘B’). Model A takes regression into consideration in the factor “Commitment to a Place”, which has a very low coefficient of determination R2 and an insignificant model (p=0.157). Model B, “Affection for a Place”, shows R2 also with a low value and an insignificant model (p=0.467). In both factors, the respective variables observed did not show significant statistical differences in the regression.

Two models with highly significant p-values can be observed in the regression. On the one hand there is the model C, “Belonging to a Place”, and the model D, “Identifying with a Place’”, with a R2 of 0.05 and 0.04, respectively. On the other hand, the nationality of the tourists significantly affects both factors of the Sense of Place. The variables “Age” and “Education” also significantly affect “Identification with a Place”. To understand how these variables affect the dimensions of the Sense of Place, tests of differences of variances among the groups that make up the observed variables were produced. These are shown in Table 8.

| Table 8 Linear Regression Models Of The Factors Of Sense Of Place |

||||

| Coefficients B | (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) |

| Commitment to a Place | Affection for a Place | Belonging to a Place | Identifying with a Place | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Constant | 3.297 | 4.175 | 3.374 | 3.531 |

| Gendera | - 0.083 | 0.131 | 0.147 | 0.075 |

| Age | 0.093* | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.122* |

| Education | - 0.133 | - 0.079 | 0.002 | - 0.120 |

| Profession | - 0.060 | - 0.085 | - 0.022 | - 0.032 |

| Nationality EUa | - 0.266* | - 0.210* | - 0.415* | - 0.343* |

| Profile of Stay | ||||

| Constant | 3.348 | 4.334 | 3.647 | 3.595 |

| Duration of stay | - 0.128 | -0.012 | - 0.070 | 0.070 |

| Type of accommodation |

0.013 | 0.014 | 0.063 | 0.003 |

| Accompanied?a | - 0.187 | - 0.259 | - 0.145 | - 0.177 |

Note: *Sig. p ≤ 0.05; a Binary qualitative variables have ‘0’ as their base; p-value obtido na análise da ANOVA da regressão.

After the variances of the regression models of the sociodemographic variables had been analysed, it was found that all the models showed p-values ≤ 0.005, which is to say that the four models are highly significant. The level of significance in the regression models of nationality and of age contributed to this result. To understand how these variables affect these dimensions of the “Sense of Place”, tests were produced of the average differences of the groups that comprise the variables “Nationality” and “Age”, set out in Tables 9 and 10.

| Table 9 Analysis of variances of nationality in the dimensions of ‘sense of place’ |

||||||

| Levene F Test (Sig) | T test (sig, 2-talied)* | European Nationality (EU28) | N | Average | Standard Deviation | |

| Belonging to a Place | 0.066 (0.798) | -4.135 (0.000) | European | 285 | 33.193 | 101.995 |

| Non-European | 203 | 37.069 | 102.158 | |||

| Commitment to a Place | 0.100 (0.752) | -2.619 (0.009) | European | 285 | 28.228 | 102.251 |

| Non-European | 202 | 30.668 | 0.99962 | |||

| Affection for a Place | 0.116 (0.733) | -2.157 (0.031) | European | 290 | 39.603 | 105.930 |

| Non-European | 209 | 41.651 | 102.740 | |||

| Identifying with a Place | 0.079 (0.779) | -3.504 (0.001) | European | 285 | 33.953 | 103.747 |

| Non-European | 204 | 37.255 | 101.323 | |||

Note: *Assuming that the variances are homogenous and the averages are different.

| Table 10 Analysis of the variances of the age groups in the dimensions ‘commitment to a place’ and ‘identifying with a place’ |

||||||

| Test Levene F (Sig) | Test Tukey (Sig.) | Age (years) | N | Average | Standard Deviation | |

| Commitment to a Place | 2.418 (0.035)** | Sig. ≥ 0.05 | Under 20 | 45 | 27.500 | 109.881 |

| between 20 and 30 | 135 | 27.389 | 103.388 | |||

| between 30 and 40 | 108 | 29.074 | 100.907 | |||

| between 40 and 50 | 90 | 30.556 | 0.93525 | |||

| between 50 and 60 | 64 | 31.172 | 0.92149 | |||

| over 60 | 45 | 31.556 | 112.600 | |||

| Identifying with a Place | 3.149 (0.008)** | (0.045)*** | Under 20 | 45 | 33.333 | 0.95611 |

| between 20 and 30 | 134 | 33.333 | 104.614 | |||

| between 30 and 40 | 108 | 34.815 | 100.604 | |||

| between 40 and 50 | 91 | 36.703 | 0.98820 | |||

| between 50 and 60 | 64 | 37.865 | 0.99977 | |||

| over 60 | 47 | 38.014 | 119.310 | |||

Note: **Assuming that the variances are not homogeneous; *** Significant differences of average age between the groups (20-30 e 50-60). All the significances have a margin of error of 95%.

From the analysis of variances between population groups of the most significant variables, it can be deduced that nationality or, rather, being European differs significantly in the dimensional aspects that constitute the ‘Sense of Place’. Assuming that the variances are equal, there are still significant differences between the average score factors of these aspects of the “Sense of Place”.

As far as age is concerned, the analysis of variance reveals the existence of significant differences in the average of the score factors in “Commitment to a Place” and in “Identity with a Place”. In the first aspect, assuming that the variances are equal, we find significant differences among all the age groups. In the second aspect, we can find significant differences, in particular, those between the youngest age groups and the oldest.

Conclusion

This article was intended to demonstrate that the concept of “Sense of Place” is multidimensional and has relevance to studies of both marketing and tourism. With recourse to a diverse literature on “sense of place”, originating in studies of human geography, it was possible to develop a research instrument (a survey questionnaire validated by a focus group and interviews with specialists in tourism and marketing) applied to non-resident tourists in Portugal.

The questionnaire, constructed by the authors and validated by the focus group, provided data in two sections: one referring to socio-demographic information about the respondents and the other made up of 17 questions that reflect the concepts addressed in the review of the literature on the topic. The empirical work was performed during the summer of 2013 and the questionnaire was answered by 500 non-resident tourists who were found in the Lisbon International Airport.

The sample takes into consideration a descriptive analysis of the socio-demographic data of the tourists surveyed. We can find distributions identical to the official reports by the competent authorities, like “Turismo de Portugal”. Most of the tourists came from European countries such as France, Germany and Spain; however, we encountered a significant fraction of non-Europeans (38.6%), including tourists from Brazil.

In general, the tourists surveyed were aged from 25 to 65, with higher education (71%) and their professional situation was “employed” (67%). The same tourists spent at least a week in Portugal, lodged in hotels (63%) and accompanied by their families. For more than three-quarters of these tourists (78%), Portugal was their last holiday destination in that period.

The data collected resulted in the validation, by means of Factorial Analysis, of four “dimensions” making up the “Sense Place” (i.e. “Belonging to a Place”, “Commitment to a Place”, “Affection for a Place” and “Identifying with a Place”). The data were then introduced into a regression model with the objective of constructing a profile of tourists. On the basis of this profile were the socio-demographic variables of the tourists and the previously-mentioned dimensions.

The results of the Factorial Analysis revealed that “Belonging to a Place” is the dimension that contributes most to explaining the formation of the tourist’s “Sense of Place”, also showing a high level of agreement (3.5). To strengthen this dimension, tourists with non-European nationalities contributed significantly, although, in fact, there are significant differences between Europeans and non-Europeans in all the dimensions of the “Sense of Place”.

This phenomenon, of a persistence of greater perception of “Sense of Place” on the part of non-European tourists, leads us to conjecture that the fact of tourists coexisting with various nationalities in cultural and geographic spaces very different from the European, showing different values and intentions in comparison with a European country like Portugal, and having psychological values of introspection and perception of exterior reality very different from those of the resident tourists or citizens of other European countries, sharpens their awareness and appreciation of European places that they have the leisure to stay in and observe.

The “Commitment to a Place”, with an average concordance lower than the rest (2.9), however, is also the dimension that contributes in high degree to the formation of “Sense of Place”. This dimension of perception also reveals the differences in the ages of the tourists. In fact, significant differences exist among the tourists in terms of age and perceptions are stronger in older age groups.

This phenomenon is also reflected in the dimension “Identifying with the Place”, which, too, shows significant differences among the tourists in terms of age, in particular, between those in the age groups 20 to 30 and 50 to 60. In spite of the fact that the average value of perception of this dimension is relatively high (3.5), its contribution to the formation of “Sense of Place” is the smallest.

The empirical results indicate the importance and the impact of age in the construction of the “Sense of Place” of the tourist destination, in particular, in what concerns the perceptions of commitment to and identity with tourist places. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the oldest tourists have a greater desire to dedicate themselves, even with some “sacrifice”, to the protection of tourist destinations.

On the other hand, as some authors point out, the existing ambience in tourist places, like the symbols or the physical aspects, at any given moment, are mixed with the personalities of the individual visitors, who project their own identity on to the places, an effect that arises with greater intensity among tourists of advanced age.

References

- Aaker, D.A., Kumar, V., & Leone, R. (2012). Marketing research, (11th Edition). Wiley Global Education. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=YkIcAAAAQBAJ

- Acedo, A., Painho, M., & Casteleyn, S. (2017). Place and city: Operationalizing sense of place and social capital in the urban context. Transactions in GIS, 21(3), 503-520.

- Anholt, S. (2006). The Anholt-GMI city brands index: How the world sees the world's cities. Place branding, 2(1), 18-31.

- Azizi, F. (2018). Modeling the relationship between sense of place, social capital and tourism support. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 11(3), 547-572.

- Campelo, A., Aitken, R., Thyne, M., & Gnoth, J. (2014). Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 154-166.

- Chang, T.C. (1997). From “instant Asia” to “multi-faceted jewel”: Urban imaging strategies and tourism development in Singapore. Urban Geography, 18(6), 542-562.

- Clarke, D., Murphy, C., & Lorenzoni, I. (2018). Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 81-89.

- Counted, V. (2016). Making sense of place attachment: Towards a holistic understanding of people-place relationships and experiences. Environment, Space, Place, 8(1), 7-32.

- D’Orey, F. (2014). A construção e escolha dos destinos turísticos nos processos de atualização da identidade individual e social. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas Y Sociales. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10115/13566

- Deutsch, K., Yoon, S.Y., & Goulias, K. (2013). Modeling travel behavior and sense of place using a structural equation model. Journal of Transport Geography, 28, 155-163.

- Devine-Wright, P., & Clayton, S. (2010). Introduction to the special issue: Place, identity and environmental behaviour.

- Dhamija, S., Agrawal, A., & Kumar, A. (2011). Place marketing creating a unique proposition. BVIMR Management Edge, 4(2).

- d'Orey, FG (2015). The feeling of place and the construction of tourist destinations, proposed conceptual model. European Journal of Applied Business and Management, 1 (1).

- Foote, K.E., & Azaryahu, M. (2009). Sense of place.

- George, B., & George, B. (2012). Past visits and the intention to revisit a destination: Place attachment as the mediator and novelty seeking as the moderator.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R.L. (2013). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education Limited. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VvXZnQEACAAJ

- Harman, H.H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=e-vMN68C3M4C

- Jarratt, D., Phelan, C., Wain, J., & Dale, S. (2018). Developing a sense of place toolkit: Identifying destination uniqueness. Tourism and Hospitality Research. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1467358418768678

- Johnson, R. A., & Wichern, D. W. (2002). Applied multivariate statistical analysis, 5.

- Jorgensen, B.S., & Stedman, R.C. (2006). A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. Journal of Environmental Management, 79(3), 316-327.

- Kaltenborn, B.P. (1998). Effects of sense of place on responses to environmental impacts: A study among residents in Svalbard in the Norwegian high Arctic. Applied Geography, 18(2), 169-189.

- Larson, S., De Freitas, D.M., & Hicks, C.C. (2013). Sense of place as a determinant of people's attitudes towards the environment: Implications for natural resources management and planning in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 117, 226-234.

- Lavrakas, P.J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Sage Publications.

- Lin, C.C., & Lockwood, M. (2014). Assessing sense of place in natural settings: a mixed-method approach. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 57(10), 1441-1464.

- Malhotra, N.K. (2012). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Bookman Editora. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=FtdIFOgTP8UC

- Marôco, J. (2010). Analysis of structural equations: Theoretical fundamentals, software & applications. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=oYK1MG8tc3UC

- Muñiz Martinez, N. (2012). City marketing and place branding: A critical review of practice and academic research. Journal of Town & City Management, 2(4).

- Pike, K. L. (2015). Language in relation to a unified theory of the structure of human behavior. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & co KG.

- Poljanec-Bori?, S., Wertag, A., & Šiki?, L. (2018). Sense of place: Perceptions of permanent and temporary residents in Croatia. Turizam: me?unarodni znanstveno-stru?ni ?asopis, 66(2), 177-194.

- Proshansky, H.M. (1978). The city and self-identity. Environment and behavior, 10(2), 147-169.

- Proshansky, H.M., Fabian, A.K., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57-83.

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. London: Pion.

- Rizzi, P., & Dioli, I. (2010). Strategic planning, place marketing and city branding: The Italian case. Journal of Town & City Management, 1(3), 300-317.

- Roult, R., Adjizian, J.M., & Auger, D. (2016). Sense of Place in Tourism and Leisure: the Case of Touring Skiers in Quebec. Almatourism-Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development, 7(13), 79-94.

- Shamai, S. (1991). Sense of place: An empirical measurement. Geoforum, 22(3), 347-358.

- Shamai, S., & Ilatov, Z. (2005). Measuring sense of place: Methodological aspects. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(5), 467-476.

- Shamsuddin, S., & Ujang, N. (2008). Making places: The role of attachment in creating the sense of place for traditional streets in Malaysia. Habitat International, 32(3), 399-409.

- Smaldone, D., Harris, C.C., Sanyal, N., & Lind, D. (2005). Place attachment and management of critical park issues in Grand Teton National Park. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 23(1).

- Smith, S. (2015). A sense of place: Place, culture and tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 220-233.

- Stedman, R. C. (2003). Is it really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society &Natural Resources, 16(8), 671-685.

- Stedman, R., Beckley, T., Wallace, S., & Ambard, M. (2004). A picture and 1000 words: Using resident-employed photography to understand attachment to high amenity places. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(4), 580-606.

- Tan, S.K., Tan, S.H., Kok, Y.S., & Choon, S.W. (2018). Sense of place and sustainability of intangible cultural heritage–The case of George Town and Melaka. Tourism Management, 67, 376-387.

- Tuan, Y.F. (1974). Topophilia: A study of environmental attitudes, perceptions and vallues.

- Tuan, Y.F. (1979). Space and place: humanistic perspective. In Philosophy in geography, pp.387-427. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Tuan, Y.F. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. U of Minnesota Press.

- Tucker, L.R., Koopman, R.F., & Linn, R.L. (1969). Evaluation of factor analytic research procedures by means of simulated correlation matrices. Psychometrika, 34(4), 421-459.

- Turismo de Portugal, & GFK. (2012). Estudo da Satisfação de Turistas. Retrieved from www.turismodeportugal.pt

- Vorkinn, M., & Riese, H. (2001). Environmental concern in a local context: The significance of place attachment. Environment and Behavior, 33(2), 249-263.

- Wang, Y., & Pizam, A. (Eds.). (2011). Tourism destination marketing and management: Collaborative stratagies. Cabi Prentice Hall. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?id=VUHrAAAAMAAJ

- Witt, S.F., & Moutinho, L. (1994). The study of destination marketing.

- Yuksel, A., Yuksel, F., & Bilim, Y. (2010). Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tourism Management, 31(2), 274-284.