Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Theories of Job Satisfaction in the Higher Education Context

Nteboheng Patricia Mefi, Walter Sisulu University

Samson Nambei Asoba, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

In South Africa, stagnant economic growth and high unemployment rates have called for solutions from all key national institutions, including institutions of higher learning, to provide solutions. This call must be considered within the transformation discourse that arose in South Africa after the fall of the apartheid regime in 1994 and the need to equalize educational opportunities, reduce poverty and improve lives through education. All this underscores the need for a vibrant motivated, satisfied and dedicated workforce. To explain and understand the phenomena of job-satisfaction several theories have been suggested by Maslow, Vroom, Adams, McGregor, Herzberg, Alderfer’s and other authors, however theories on employee job satisfaction varies with time and place, the old theory needs to be either modified, or replaced with a new model. The study attempt to synthesize the theories of job satisfaction in the Higher Education Institution in Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. The study adopted a desktop that was designed primarily as a descriptive study to source literatures on motivation, job satisfaction, and theories. Theories are neither right nor wrong rather it depends on the context where it is applied. Theories need to be restructured according to the new areas of research in human psychology. The evidence established from this study suggest theories of job satisfaction have to be tested against these emerging factors of positive psychology and their impact on human behaviour at individual, group and organizational levels in other Higher Education institutions in South Africa.

Keywords

Motivation, Job Satisfaction, Theories, University.

Introduction

In South Africa, stagnant economic growth and high unemployment rates have called for solutions from all key national institutions, including institutions of higher learning, to provide solutions (Urban & Richard, 2015; Malebana, 2016; Oni & Mavuyangwa, 2019). This call must be considered within the transformation discourse that arose in South Africa after the fall of the apartheid regime in 1994 and the need to equalize educational opportunities, reduce poverty and improve lives through education. All this underscores the need for a vibrant motivated, satisfied and dedicated workforce, which is propelled by an effective leadership style in the South African Higher Education system. This study focuses on the Higher Education (HE) context whose success is largely dependent on the efficiency and effectiveness of human capital. This reliance on people’s competencies and skills makes it important to understand job satisfaction and its precedents. In a study of job satisfaction and occupational stress in the HE system in South Africa, Ngirande and Mjoli (2020) propound that workforce satisfaction should be understood as an important factor for effectiveness. Organisations need effective leaders and employees to achieve their objectives (Hamidifar, 2009).

According to O’Leary et al. (2009) job satisfaction is the feeling of fulfilment or enjoyment which people derive from their jobs. To explain and understand the phenomena of job-satisfaction several theories have been suggested (Maslow, Vroom, Adams, Herzberg’s, McGregor etc.) and this effort continues forever because as things change, the old theory needs to be either modified, or replaced with a new model. According to Robbins et al. (2009) motivation is a drive toward out come and satisfaction is the outcome already experience. Robbins et al. (2009) further argued that motivation is the process that account for an individual’s intensity, direction, and persistence of effort toward attaining goal. Motivation refer to the interaction between individual and a situation. The differences in motivation are driven by the situation. For example, an individual student may be driven to succeed (Sabri et al., 2011). But that same students who finds it difficult to read a textbook for more than 20 minutes may devour a harry Potter book in a day (Malik, 2010). Therefore, the level of motivation varies both between individuals and within individuals at different times. Following arguments presented in the report from CHE (2016), theories influencing employee job satisfaction varies with time and place. This implies that constant research on these phenomena is important to ensure that any available practices are relevant to time and place. Authors such as Kebede and Demeke (2017); Okoli (2018); Kiplangat (2017) have done several studies on motivation and job satisfaction in Higher Education Institution (HEIs) in countries like Kenya, Nigeria and Ethiopia, none of these studies has focused on HEIs in South Africa and particularly in the Eastern Cape Province. Hence, this study focuses on the theories of job satisfaction in higher education context in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa Abdulla et al. (2010).

Literature Review

The literature review is discussed under the following headings: job satisfaction, theories, synthesising the diversity of the theories, and cultural limitations.

Job Satisfaction

O’Leary et al. (2009) argue that job satisfaction is generally conceived as a feeling of fulfilment or enjoyment which people derive from their jobs and is positively related to employee health and job performance. Job satisfaction also indicates a good relationship with staff and colleagues, control of time off and adequate resources. According to Gunlu et al. (2009), to accomplish customer satisfaction, the job satisfaction of employees in the organisation is necessary. Employees who experience job satisfaction are likely to execute their duties well, leading to high performance and efficient service, which will directly increase the productivity of the organisation (Gunlu et al., 2009); Lockwood (2007) state that managers are the core points of the service production and therefore, their impact on the employees is very important. If managers are not satisfied and not committed to the organisation, their effectiveness in managing an organisation is in question (Clark et al., 1996).

There are three facets to job satisfaction (Gunlu et al., 2009), which can be classified as intrinsic, extrinsic and general reinforcement factors. To evaluate intrinsic job satisfaction, the key factors of achievement, responsibility, independence, creativity, security, self-directiveness, authority, activity and ability utilisation must be addressed (Gunlu et al., 2009). For extrinsic job satisfaction, the factors to consider are advancement, company policy, supervision-human and supervision-technical relations, compensation, and recognition. When intrinsic and extrinsic factors are summed up then general job satisfaction is formed (Gunlu et al., 2009). According to Toker (2011), most of the studies on employee job satisfaction have related to profit-making industrial and service organisations (Smit, 2013; Smit, 1969).

There has been a growing feeling of wanting to know about job satisfaction of employees in HEIs. Toker (2011) further indicates that the reasons for this increasing interest are the reality that HEIs are labour intensive, their budgets are predominantly devoted to personnel and their effectiveness is largely dependent on their administrative and academic staff (Mohammad et al., 2011).

Theories of Job Satisfaction

According to Saif et al. (2012) there is nothing as practical as a good theory. A theory is a systematic grouping of interdependent concepts and principles resulting in a framework that ties together a significant area of knowledge (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999). More precisely, a theory identifies important variables and links them to form “tentative propositions” that can be tested through research (Newstrom, 2007).

Saif et al. (2012) state that job satisfaction theories are commonly grouped according to the nature of theories or their chronological appearance. Content theories include Maslow’s needs hierarchy, Herzberg’s two-factor theory (Theory X and Theory Y), Alderfer’s ERG theory and McClelland’s theory of needs. Process theories include behaviour modification, cognitive evaluation theory, goal-setting theory, reinforcement theory, expectancy theory and equity theory (Shajahan & Shajahan, 2004).

Luthans (2005)mentions content theories, such as Maslow’s needs hierarchy, two-factor and ERG, process theories such as the expectancy theory and Porter and Lawler’s model, and contemporary theories such as equity, control and agency theories. Robbins and Coulter (2005) categorize the theories chronologically, earlier theories being Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, theory X and Y, the two-factor theory (Sengupta, 2011). Contemporary theories include McClelland’s theory of needs, the goal-setting theory, the reinforcement theory, the job design theory (job characteristics model), the equity theory and the expectancy theory. However, it is notable that content and process theories have become standard classification (Konrad, 2000).

Content Theories

Content theories centre on the needs, drives and incentives/goals and their prioritization by the individual to get satisfaction (Luthans, 2005). Experts have listed biological, psychological, social and higher-level needs of human beings. Interestingly, almost all the researchers categorise these needs into primary, secondary and high-level employee requirements, which need to be fulfilled if the worker is to be motivated and satisfied. The following are the most well-known content theories that are widely used by management (Saif et al., 2012).

Maslow’s Theory of Motivation/Satisfaction (1943)

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is the most widely known theory of motivation and satisfaction (Kaur, 2013). Building on human psychology and clinical experiences, Maslow argued that individual motivational needs could be ordered as in a hierarchy. Some needs take precedence over others. Once a need is satisfied, it no longer motivates the person (Luthan, 2005); Maslow (1943) identified five levels of needs:

- Physical needs (drink, air, shelter, sleep, sex)

- Safety needs (police, schools, business, medical care and physical protection)

- Social (friendship, family and work)

- Esteem/achievement needs (prestige given by others) and

- Self-actualisation (Seeking personal growth and self-fulfilment).

An individual’s needs are influenced by the importance attached to various needs and the level to which an individual wants to fulfil these needs (Karimi, 2008); Saifet al. ( 2012) indicate that Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs was the first motivation theory that laid the foundation for the theories of job satisfaction. This theory serves as a good start from which researchers can explore the problem of job satisfaction in different work situations (Saifet al., 2012).

Organisational/Managerial Applications

The greatest value of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory lies in the practical implications it has for management and organisations (Kaur, 2013). The rationale behind the theory is that it can suggest to managers how they can make their employees or subordinates self-actualised. This is because self-actualised employees are likely to work at their maximum creative potential. Therefore, it is important to make employees achieve this state by helping them to meet their needs. Organisations can implement the following strategies to attain this stage:

- Recognise employees’ accomplishments: Recognising employees’ accomplishments is an important way to make them satisfy their esteem needs. This could take the form of awards but it should be noted that according to Kaur (2013), awards are effective at enhancing esteem only when they are linked to desired behaviours. Awards that are too general fail to meet this specification.

- Provide financial security: financial security is an important type of safety need. Organisations should motivate their employees’ needs to make them financially secure by involving them in profit-sharing in the organisation.

- Provide opportunities to socialise: socialisation is one of the factors that encourage employees to feel the spirit of working as a team. When employees work as a team, they tend to increase their performance.

- Promote a healthy workforce: companies can help their employees’ physiological needs by providing incentives to keep them healthy both physically and mentally.

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory (1959)

Herzberg conducted a motivational study in which he interviewed 200 accountants and engineers. He used the critical incident method of data collection with two questions: a) when you feel particularly good about your job, what makes you feel good? And b) when you feel exceptionally bad about your job, what is the reason? Recording these good and bad feelings, Herzberg argued that there are job-satisfiers (Motivators) related to job content and job-dissatisfies (Hygiene Factors) concerned with job context (Falkenburg & Schyns, 2007). Motivators include achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility and advancement. The hygiene factors do not motivate or satisfy but rather prevent dissatisfaction. These factors are contextual, such as company policy, administration, supervision, salary, interpersonal relations and working conditions (Herzberg et al., 1959).

Saif et al. (2012) indicate that Herzberg’s theory is the most useful model in studying job satisfaction. For instance, Karimi (2008) found that it helped to understand job satisfaction in educational settings. Getahun et al. (2007) add that others have used it as a theoretical framework for assessing police officers’ job satisfaction. However, a review of literature revealed criticisms of the motivator-hygiene theory (Karimi, 2008). For example, the theory ignores individual differences and wrongfully assumes that all employees react similarly to the changes in motivators and hygiene factors (Wikipedia, 2009).

Mcgregor’s Theory X and Theory Y (1960)

After observing and understanding how managers handle employees, McGregor (1960) proposed that the manager’s view about the nature of human being is founded on a group assumptions and that managers change their behaviour toward their subordinates according to these assumptions about different employees (Robbins, 1998).

Assumptions of Theory X (negative view of human beings)

- Human beings have an inherent dislike of work and avoid it if possible.

- Due to this behaviour, people must be forced, commanded, directed and threatened with penalties to make them work.

- They prefer to be directed, avoid responsibility, have little ambition and want security (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999).

Assumptions of Theory Y (positive view of human beings)

- Physical and mental effort in work is as natural as play and rest.

- External control and threats are not the only means of producing effort. People can practise self-direction and self-control in achieving objectives.

- The degree of commitment to objectives is determined by the size of the reward attached to achievement.

- Under proper conditions, human beings learn and not only accept responsibility but also seek it (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999).

Mcclelland’s Needs Achievement Theory (1961)

McClelland (1961) postulates that some people have a compelling drive to succeed and therefore strive for personal achievement rather than the rewards of success themselves Crede et al. (2007). They have the desire to perform better than before, therefore they like challenging jobs and behave as high achievers (Shajahan & Shajahan, 2004; Jahangir, 2004). This theory focuses on the achievement motive, hence it is called the achievement theory but it is founded on the following achievement, power and affiliation motives:

- Achievement: this is the drive to excel and achieve beyond the standards of success.

- Power: refers to the desire to have an impact, to be influential and to control others (Robbins & Coulter, 2005; Shajahan & Shajahan, 2004).

- Affiliation: is the desire for having friendly and close interpersonal relationships (Shajahan & Shajahan, 2004). Those with high affiliation prefer cooperative rather than competitive situations (Robbins & Coulter 2005).

Alderfer’s Erg Theory (1969)

Alderfer (1969) explored Maslow’s theory and linked it with practical research. He regrouped Maslow’s list of needs into three classes of needs: Existence, relatedness and growth, thereby calling it ERG theory. His classification absorbs Maslow’s division of needs into existence (physiological and security needs), relatedness (social and esteem needs) and growth (self-actualisation) (Saif et al., 2012). Alderfer suggests a continuum of needs rather than hierarchical levels or two factors of needs. Unlike Maslow and Herzberg, Alderfer does not suggest that a low-level need must be fulfilled before a high-level need becomes motivating or that deprivation is the only way to activate a need (Luthans, 2005).

Process Theories

Process theories try to explain how the motivation takes place. Similarly, the concept of expectancy from cognitive theory plays a dominant role in the process theories of job satisfaction (Luthan, 2005). This theory strives to explain how the needs and goals are fulfilled and accepted cognitively (Durant et al., 2006; Bodla & Naeem, 2008). Several process-based theories have been suggested and some of these theories have been used by researchers as hypotheses, tested and found thought-provoking. The following are well-known theoretical models for process motivation (Durant et al., 2006).

Adam’s Equity Theory (1963)

Adams' Equity Theory is the balance between the effort an employee puts into their work (input-hard work, skill level, acceptance, enthusiasm) and the result they get in return (output-salary, benefits, intangibles such as recognition). This ratio is then compared with the input-output ratio of other workers and if this ratio is equal to that of the others, a state of equity is said to exist (Robbins & Coulter, 2005). The equity theory has been studied extensively over the past few decades under the title of distributive justice (Yusof & Shamsuri, 2006). It was found that rewards increase employee satisfaction only when these rewards are valued and perceived as equitable by the employees (Durant et al., 2006).

Vroom’s Expectancy Theory (1964)

According to Vroom (1964), people are motivated to work to achieve anticipated results and what they do will help them in achieving their goals (Saif et al., 2012). Vroom’s theory is based on three major variables, motivated by anticipated results or consequences.

- Valence;

- Expectancy; and

- Instrumentality.

Valence is the strength of an individual’s values and his/her personal needs for a particular output. Expectancy is what employees expect from their efforts and the probability that a particular effort will lead to good performance. Instrumentality is the degree to which an employee’s performance is good enough to achieve the desired result. For example, a person can be motivated toward better performance to realize promotion (Luthans, 2005).

The expectancy theory recognizes the importance of various individual needs and motivations (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999). It suggests that rewards used to influence employee behaviour must be valued by individuals (Durant et al., 2006). Therefore, this theory is considered the most comprehensive theory of motivation and job satisfaction (Robbins & Coulter, 2005). It explains that motivation is a product of these factors-how much a reward is wanted (valence), the estimate of probability that effort will lead to the successful performance and the estimate that performance will result in getting the reward (instrumentality) (Newstrom, 2007).

Porter-Lawler Expectancy Theory Model (1968)

This model is a very popular explanation of the job satisfaction process. Porter and Lawler (1968b) stress that effort does not lead directly to performance. Rather, it is moderated by the abilities and traits and the role perceptions of an employee. Furthermore, satisfaction is not dependent on performance but is determined by the probability of receiving fair rewards (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999). The Porter-Lawler model suggests that motivation is affected by several interrelated cognitive factors, such as motivation results from the perceived effort-reward probability. However, before this effort is translated into performance, the abilities and traits and role perceptions of employees on the efforts used for performance are considered. Furthermore, it is the perceived equitable rewards that determine the job satisfaction of the workforce (Luthans, 2005).

Locke’s Goal-Setting Theory (1968)

Locke (1968) asserted that intentions could be a major source of motivation and satisfaction (Saif et al., 2012). Some specific goals lead to increased performance, for example, difficult goals lead to higher performance than easy goals and feedback triggers higher performance than no feedback. Likewise, specific hard goals produce a higher level of output than generalised goals of ‘do your best’ (Saif et al., 2012). Furthermore, people will do better when they are motivated by well-defined goals and feedback as feedback identifies discrepancies between what have they done and what they want to do. All the studies that tested the goal-setting theory demonstrated that challenging goals with feedback is a motivating force (Robbins & Coulter, 2005). In it, he demonstrated that employees are motivated by clear, well-defined goals and feedback and that a little workplace challenge is no bad

The goal-setting theory on employee motivation is essentially linked to high performance and has been well researched globally. For example, it has been applied to the study of more than 40 000 participants’ performance in well over 100 different tasks in eight countries in both laboratory and field settings (Durant et al., 2006). The goal-setting theory suggests that difficult goals demand focus on problems, an increased sense of goal importance and encouraging persistence to achieve the goals. The goal-setting theory can be combined with cognitive theories to better understand the phenomena, for example, the employees’ mindset and perception that they are successfully contributing to meaningful work and therefore foster enhanced work motivation (Moynihan & Pandey, 2007).

Hackman and Oldham’s Job Characteristics Theory (1975)

Job characteristics are based on the idea that the job itself is key to employee motivation. Hackman and Oldham’s original 1975 job characteristics theory was revised in 1980 (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). Their original formulation of the job characteristics theory stated that the outcomes of job redesign were influenced by several moderators. These moderators include the differences to which various employees desire personal or psychological progress (Durant et al., 2006). The clarity of tasks leads to greater job satisfaction because greater role clarity creates a workforce that is more satisfied, committed and involved in work (Moynihan & Pandey, 2007).

Jobs that are rich in motivating characteristics trigger psychological states, which in turn increase the likelihood of desired outcomes. For example, the significance of a task can ignite a sense of meaningfulness of work that leads to effective performance (Durant et al., 2006). More precisely, the model states five core job characteristics impact three critical psychological states (experienced meaningfulness, experienced responsibility for outcomes and knowledge of the actual results) which in turn influence work outcomes (job satisfaction, absenteeism, work motivation) (Wikipedia, 2009). The five core job characteristics are:

- Skill variety: skill variety describes the varieties of skills, abilities or talents necessary to complete the job. These activities should not only be different but they also need to be distinct enough to require different skills.

- Task identity: task identity defines the extent of what is needed to complete the whole job

- Task significance: task significance refers to the importance of the job and how the job has changed the lives of people, their environment and the external environment.

- Autonomy: autonomy is the degree to which the jobholder is free to schedule the pace of his or her work and determine the procedures to be used.

- Feedback: feedback is the information employees receive about the effectiveness of their performance. Feedback not only refers to supervisory feedback but also the ability to observe the results of one’s own work.

These core dimensions are associated sufficiently great with job satisfaction and high employee motivation. Hackman and Oldham’s model claims that attention to these five job characteristics produces three critical psychological states (Tosi et al., 2000):

- Meaningfulness of work: this results from belief in the intrinsic value/meaning of the job. For example, teachers may experience meaningfulness of work, even in difficult working conditions because of the conviction that their efforts make a difference in the lives of their pupils.

- Responsibility for outcomes of work: job efforts are perceived as causally linked to the results of the work.

- Knowledge of work activities, which can be qualified as feedback. The employee can judge the quality of his/her performance.

According to the model, different job dimensions contribute to different psychological states. Job meaningfulness focuses on mechanisms and processes such as skills variety, task identity and task significance. Experienced responsibility is a function of autonomy and knowledge of results is dependent on feedback. The psychological state that receives the most attention in Hackman and Oldham’s study is the meaningfulness of work (Vanden Berghe, 2011)

According to Vanden Berghe (2011) the presence of these critical states can in turn increase the probability of positive work outcomes, especially for employees with a high growth-need. The positive work outcomes are:

- High internal work motivation: motivation is caused by the work itself;

- High-quality performance: this results from the meaningfulness of work, however, quality does not necessarily imply quantity;

- High job satisfaction; and

- Low absenteeism and turnover.

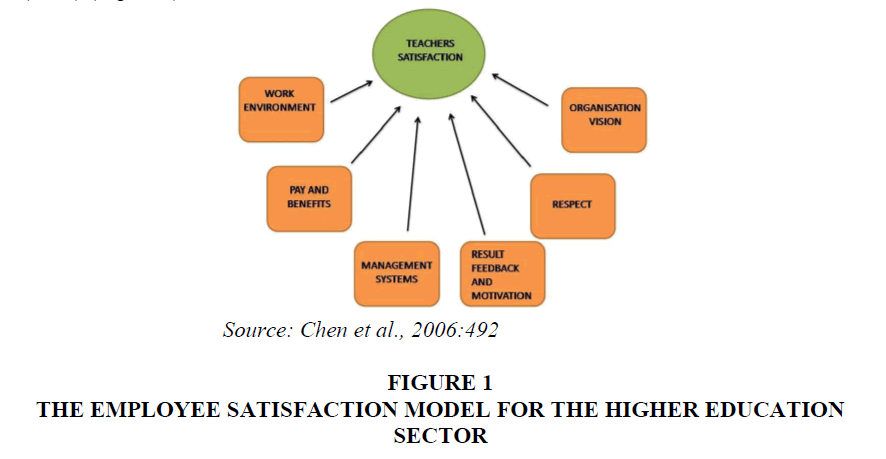

The Employee Job Satisfaction Model of Higher Education

Employee satisfaction reflects the feeling of fulfilment that people’s needs and desires are met and the extent to which this is positively related to other employees, employee health and job performance (Masalesa, 2016). This employee satisfaction model was designed by Chen et al. (2006) (Figure 1).

Synthesising the Diversity of Theories

Discussion

Saif et al. (2012) report that one of the errors when using theoretical frameworks is the tendency to overlook the need for compromising or blending, while there is little doubt that the ability to compromise with the least undesired consequences is the essence of art (Koontz & O’Donnell, 1972). The role of theory is to provide a means of classifying significant and pertinent knowledge (Weihrich & Koontz, 1999). Several motivational models are available, all having strengths and weaknesses, as well as advocates and critics. No model is perfect but each of them adds something to understanding the motivational and satisfaction process. While new models are emerging, there are also efforts to integrate the existing approaches (Moyhihan & Pandey, 2007; Newstrom, 2007).

Job satisfaction as a Function of other people

According to the social information processing model, job satisfaction is susceptible to the influence of others in the workplace. People are inclined to observe and copy the attitudes and behaviours of colleagues with similar jobs and interests and of superiors who are perceived as powerful and successful (Vanden Berghe, 2011).

Direct Influence by Others

Vanden Berghe (2011) identifies the positive correlations between behaviour exhibited by leaders and job satisfaction. Weiss (1978) reports great similarity in the values of employees and supervisors when the latter treat their subordinates with consideration.

Indirect influence by others

According to Bernanthos (2018), leadership is a person’s ability to influence others to achieve the goal set. Bernanthos adds that

“Motivational leadership has an indirect positive and significant impact on employee’s performance through job satisfaction”.

In a related study, DeWayne (2005) found a strong, negative correlation between person-organisation fit and turnover. This finding indirectly indicates that a lack of correspondence between an employee and the culture of a company will most likely lead to lower job satisfaction. However, the researcher believes that sometimes the best way to influence a target person or group is to indirectly influence someone who is in a better position to influence the target person (Westover, 2012).

Cultural Limitaion

In South Africa context culture is very critical in enhancing job satisfaction. Significant proportion of job satisfaction theories where developed by authors in developed world assuming that these theoretical models are workable across the globe for example these theories emphasis individualism and achievement (Robbins, 2005) whereas in South Africa “Ubuntu” is commonly practise by majority of South African. Ubuntu is the action that symbolises the humanness between human being. According to Broodryk (2006) Ubuntu refers to values such as a kind person, generous, living in harmony, friendly, modest, helpful, humble and happy towards others and the other value which very important and which shows or reveal humanness within a person (Sarker et al., 2003).

One of the values of Walter Sisulu University is to be a caring University by committing to mutual respect, ubuntu, humility, good citizenship, student centeredness and endorse and uphold all principles of Batho Pele the university is still struggling to shift from being an institution created to serve a Bantustan civil service to become a modern developmental university. The merger between Unitra, Border Technikon and Eastern Cape Technikon to Walter Sisulu University also complicated things. Lack of harmonisation and merge of the three former institutions within Walter Sisulu University also create different cultures within the university as campuses still operate as former institutions under Walter Sisulu University. Large historical imbalances from the past based on the differences between race, gender, language, social standing, education, economic status and workplace opportunities amongst others (Brevis and Vrba, 2015). This caused serious inequities within the South African society and the workforce, which includes higher education institutions. Concretely, the issue of diversity in South Africa and in South African HEIs are quite different from the same issue in the rest of the world (Strydom & Fourie, 2018; Wickramasignhe & Kumara, 2010).

Furthermore, Staff writer (2018) asserts that Batho Pele can be translated to “People First”, and has been summarised by this slogan:

“We belong, we care, and we serve.”

It is an approach to improve service delivery by getting the Public Servants to commit to and prioritise serving people. Quite literally, putting people, and their needs. The principles of Batho Pele at Walter Sisulu University and South Africa in general are as follows:

Consultation

Interact with, listen to and learn from the people you serve.

- Service standards: The standards we set are the tools we use to measure our performance.

- Redress: When people do not get what they are entitled to from the University, they have a right to redress.

- Access: All citizens have the right to equal access to the services to which they are entitled.

- Courtesy: It is important for Public servants to remember that they are employed to help the people and to give them access to the services that are their right.

- Information: Citizens should be given full, accurate information about services.

- Transparency: Be open about day to day activities, Service and administration should be run as an open book.

- Value for Money: It is very important that employees do not waste the scarce resources.

These principles together with the university values and policies, the location of the university and the history of South Africa contribute to the culture of the university.

Power Distance

People in societies where authority is obeyed without question live in a high power distance culture. In cultures with high power distance, managers can make autocratic decisions and the subordinates follow unquestionably. Many Latin and Asian countries like Malaysia, Philippines, Panama, Guatemala, Venezuela, and Mexico demonstrate high power distance but America, Canada and several countries such as Denmark, UK, and Australia are moderate or low on power distance (Rugman & Hodgetts, 2002). Although South Africa is considered as a developing country, power distance is moderate or low on power distance. For examples, according to Walter Sisulu University Policy on Policy Development for academics (2014) the senior management and academic leaders namely the Vice Chancellor, and Principal, Deputy Vice Chancellor, Registrar, Chief Operational Officer, Chief Financial Officer, Campus Rectors, Deans, Executive Directors and Heads of Departments will initiate the development of the new policy and the revisions to an existing policy. Furthermore there must be consultation within the unit or department from which the consultation is initiated. The policy draft must serve at campus senate for further input, the policy draft must serve at senate executive committee with a standard operating procedure for recommendation for Senate approval while for non-academic policies, consultation must begin at the initiate state of the policy, the draft must be tabled at Institutional Management Committee (IMC) by the relevant institutional manager with the standard operating procedure for further input. The IMC will further decide whether the policy draft should serve at the Joint Bargaining Forum/Institutional Forum for further comments. The policy draft will serve again at the IMC for final feedback before the IMC recommends that it be served at the relevant subcommittee of council through relevant institutional manager. The relevant sub-committee of council will recommend the policy to Council for approval. A well written management report that clearly shows the consultation process must always accompany the policy draft in every step of the way. Hence the university introduced the policy for drafting policies. Policies are therefore drafted to inform workers of Walter Sisulu University on how to carry out certain functions and managers manage departments by utilising the same policies.

Uncertainty Avoidance

It refers to understanding the tendency of people to face or avoid uncertainty-are they risk-takers or risk-avoiders. Research reveals that people in Latin countries (in Europe and South America) do not like uncertainty. However, nations in Denmark, Sweden, UK, Ireland, Canada and USA like uncertainty or ambiguity. While Asian countries like Japan and Korea fall in the middle of these extremes (Luthans, 2005). According to Broodryk (2006) South Africa scores 49 on this dimension and thus has a low preference for avoiding uncertainty. Low UAL societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles and deviance from the norm is more easily tolerated. In societies exhibiting low UAI, people believe there should be no more rules than are necessary and if they are ambiguous or do not work they should be abandoned or changed. Schedules are flexible, hard work is undertaken when necessary but not for its own sake, precision and punctuality do not come naturally, innovation is not seen as threatening.

Individualism is the tendency of people to look after themselves and their immediate family only. On the contrary is the collectivism, the tendency of people to belong to groups that look after each other in exchange for loyalty. For example, US, UK, Netherlands, and Canada have high individualism but Ecuador, Guatemala, Pakistan and Indonesia have low individualism (Rugman & Hodgetts, 2002). According to Broodryk (2006) South Africa, with a score of 65 is an Individualist society. This means there is a high preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only. In Individualist societies offence causes guilt and a loss of self-esteem, the employer/employee relationship is a contract based on mutual advantage, hiring and promotion decisions are supposed to be based on merit only, management is the management of individuals.

Masculinity

If the dominant values of a society are success, money and things in contrast to femininity (caring for others and the quality of life), the society is known as Masculine. Research tells that Japan, Austria, Veneuela, and Mexico are high on masculinity values than Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Netherlands while America is moderate on these two extremes (Rugman & Hodgetts, 2002). According to Broodryk (2006) South Africa scores 63 on this dimension and is thus a Masculine society. In Masculine countries people live in order to work, managers are expected to be decisive and assertive, the emphasis is on equity, competition and performance and conflicts are resolved by fighting them out.

The researchers pinpoint that there are more differences than similarities in the application of various job satisfaction theories (Luthans, 2005). For example, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs demonstrates more the American culture than the countries like Japan, Greece, or Mexico, where uncertainty avoidance characteristics are strong, safety needs would be on top of the needs hierarchy (Robbins, 2005). Despite these differences, all the theories of job-satisfaction share some similarities, for example, they encourage mangers not only to consider lower-level factors rather use higher-order, motivational, and intrinsic factors as well to motivate and thereby satisfy the workforce (Newstrom, 2007).

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was an attempt to synthesize the theories of job satisfaction in the higher Education context in Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. The study adopted a desktop that was designed primarily as a descriptive study to source literatures on motivation, job satisfaction, and theories. Theories are neither right nor wrong rather it depends on the context where it is applied. For examples, significant proportion of job satisfaction theories where developed by authors in developed world assuming that these theoretical models are workable across the globe for example these theories emphasis individualism and achievement whereas in South Africa “Ubuntu” is commonly practise by majority of South African. Ubuntu refers to values such as a kind person, generous, living in harmony, friendly, modest, helpful, humble and happy towards others and the other value which very important and which shows or reveal humanness within a person.

Furthermore, people in societies where authority is obeyed without question live in a high power distance culture. In cultures with high power distance, managers can make autocratic decisions and the subordinates follow unquestionably. Many Latin American and Asian countries demonstrate high power distance but European and North America and Australia are moderate or low on power distance.

Although South Africa is considered as a developing country, power distance is moderate or low on power distance. South Africa, with a score of 65 is an Individualist society. This means there is a high preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only. South Africa scores 63 on this dimension and is thus a Masculine society. In Masculine countries people “live in order to work”, managers are expected to be decisive and assertive, the emphasis is on equity, competition and performance and conflicts are resolved by fighting them out.

Furthermore, these theories need to be restructured according to the new areas of research in human psychology, for example, positive psychology‟ movement is now earning footings among the researchers on human motivation and job satisfaction. This thinking emerged from the argument that so far psychology has been exclusively preoccupied with controlling negative, pathological aspects of human behavior. Thus, positive psychology emerged as a scientific method to discover and promote the factors that allow individuals, groups, organizations and communities to thrive and prosper. These factors are optimism, hope, happiness, resiliency, confidence and self-efficacy. Thus, theories of job satisfaction have to be tested against these emerging factors of positive psychology and their impact on human behaviour at individual, group and organizational levels in other Higher Education institutions in South Africa.

References

- Abdulla, J., Djebarni, R., &amli; Mellahi, K. (2010). Determinants of job satisfaction in the UAE. A case study of the Dubai liolice. liersonnel Review, 40(1), 126-146.

- Alderfer, C.li. (1969). An emliirical test of a new theory of human needs. Organizational Behavior and Human lierformance, 4(2), 142-175.

- Bernanthos, B. (2018). The direct and indirect influence of leadershili, motivation and job satisfaction against emliloyees’ lierformance.

- Bodla, M.A., &amli; Naeem, B. (2008). What satisfies liharmaceutical sales-force in liakistan. The International Journal of Knowledge, Culture, &amli; Change Management, 8, 152-163.

- Brevis, T., &amli; Vrba, M (2015). Contemliorary Management lirincililes. Juta, Calie Town.

- Chen, S.H., Yang, C.C., Shiau, J.Y., &amli; Wang, H.H. (2006). The develoliment of an emliloyee satisfaction model for higher education. TQM Magazine.

- Clark, A., Oswald, A.J., &amli; Warr, li. (1996). Is job satisfaction U-shalied in age? Journal of Occuliational and Organisational lisychology, 69(1), 57-81.

- Crede, M., Chernyshenko, O.S., Stark, S., Dalal, R.S., &amli; Bashur, M.R. (2007). Job satisfaction as mediator: An assessment of job satisfaction’s liosition within the nomological network. Journal of Occuliational and Organisational lisychology, 80, 515-538.

- DeWayne, li.F. (2005). Job satisfaction of international educators. httli://www.bookliumli.com/dlis/lidf-b/9427230b.lidf. Accessed: 7 Aliril 2020.

- Durant, R.F., Kramer, R., lierry, J.L., Mesch, D., &amli; liaarlberg, L. (2006). Motivating emliloyees in a new governance era: The lierformance liaradigm revisited. liublic Administration Review, 66(4), 505-514.

- Falkenburg, K., &amli; Schyns, B. (2007). Work satisfaction, organisational commitment and withdrawal behaviour. Management Research News, 30(10), 708-723.

- Getahun, S., Sims, B., &amli; Hummer, D. (2007). Job satisfaction and organisational commitment among lirobation and liarole officers: A case study. lirofessional Issues in Criminal Justice, 3, 1-16.

- Gunlu, E., Aksarayli, M., &amli; lierçin, N.Ş. (2010). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment of hotel managers in Turkey. International Journal of Contemliorary Hosliitality Management.

- Hackman, J.R., &amli; Oldham, G.R. (1980). Hackman and Oldham job characteristics model. Retrievd from: httlis://www.yourcoach.be/en/emliloyee-motivation-theories/hackman-oldham-job-characteristics-model.lihli Accessed: 10 March 2020.

- Hamidifar, F. (2010). A study of the relationshili between leadershili styles and emliloyee job satisfaction at IAU in Tehran, Iran. Au-GSB e-Journal, 3(1).

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., &amli; Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.

- Hiroyuki, C., Kato, T., &amli; Ohashi, I. (2007). Morale and work satisfaction in the worklilace. Evidence from the Jalianese worker reliresentation and liarticiliation survey. lireliared for liresentation at the TliLS.

- Jahangir, N., Akbar, M., &amli; Haq, M. (2004). Organisational citizenshili behaviour: Its nature and antecedents. BRAC University Journal, 1(2), 75-85.

- Judge, T.A., &amli; Klinger, R. (2007). Job satisfaction: Subjective well-being at work. In Diener, E. &amli; Larsen, R. (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being. New York, NY: Guilford liublications: 393-413.

- Karimi, S. (2008). Affecting job satisfaction of faculty members of Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran. Scientific and Research Quarterly Journal of Mazandaran University, 23(6), 89-104.

- Kaur, A. (2013). Maslow’s Need Hierarchy Theory: Alililications and criticisms. Global Journal of Management and Business Studies, 3(10), 1061-1064

- Kebede, A.M., &amli; Demeke, G.W. (2017). The influence of leadershili styles on emliloyees’ job satisfaction in Ethioliian liublic universities. Contemliorary Management Research, 13(3), 165-176.

- Konrad, A.M., Ritchie, J.E., Lieb, li., &amli; Corrigall, E. (2000). Sex differences and similarities in job attribute lireferences: A meta-analysis. lisychological Bulletin, 126(4), 593-641.

- Koontz, H., &amli; O’Donnell, C. (1972). &nbsli;lirincililes of management: An analysis of managerial functions. 5th ed. New Delhi: McGraw-Hill Kogahusha Ltd.

- Lockwood, A.J. (2007). The influence of managerial leadershili style on emliloyee job satisfaction in Jordanian resort hotels.

- Locke, E.A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior &amli; Human lierformance, 3(2), 157-189.

- Luthans, F. (2002). Organisational behaviour. 9th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

- Luthans, F. (2005). Organisational behaviour. 10th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

- Malebana, M.J. (2016). Does entrelireneurshili education matter for the enhancement of entrelireneurial intention? Southern African Business Review, 20, 365-387.

- Malik, N. (2010). A study on motivational factors of the faculty members at University of Balochistan. Serbian Journal of Management, 5(1), 143–149.

- Masalesa, T.E. (2016). The imliact of leadershili aliliroaches on emliloyee satisfaction and work lierformance within a financial services (debt collection) environment in South Africa.Unliublished Master’s dissertation. liretoria: UNISA. [Online]. Available from: httli://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/19977/dissertation_masalesa_te.lidf?sequence=1&amli;isAllowed=y Accessed: 15 May 2019.

- Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. lisychological Review, 370-396.

- McClelland, D.C. (1961). The achieving society. University of Illinois at Urbana-Chamliaign's Academy for Entrelireneurial Leadershili Historical Research Reference in Entrelireneurshili. [Online]. Available from: httlis://lialiers.ssrn.com/sol3/lialiers.cfm?abstract_id=1496181## Accessed: 17 June 2019.

- McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterlirise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Mohammad, J., Habib, F.Q. &amli; Mohmad, A.A. (2011). Job satisfaction and organisational citizenshili behaviour: An emliirical study at higher learning institutions. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 16(2), 149-165.

- Moynihan, D.li., &amli; liandey, S.K. (2007). Finding workable levers over work motivation comliaring job satisfaction, job involvement, and organisational commitment. [Online]. Available from: httli://ssrn.com/abstract=975290 Accessed: 13 March 2019.

- Mustaliha, N., &amli; Zakaria, Z.C. (2013). The effect of liromotion oliliortunity in influencing job satisfaction among academics in Higher liublic Institutions in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(3), 20-26.

- Newstrom, J.W. (2007). Organisational behaviour: Human behaviour at work. New Delhi: Tata Mcgraw-Hill.

- Ngirande, H., &amli; Mjoli, T.Q. (2020). Uncertainty as a moderator of the relationshili between job satisfaction and occuliational stress, SA Journal of Industrial lisychology/SA Tydskrif vir Bedryfsielkunde, 46(1), 1676-685.

- O’Leary, li., Wharton, N., &amli; Quinlan, T. (2009). Job satisfaction of lihysicians in Russia. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 22(3), 221-231.

- Okoli, I.E. (2018). Organizational climate and job satisfaction among academic staff: Exlierience from selected lirivate universities in Southeast Nigeria.&nbsli;International Journal of Research in Business Studies and Management, 5(12), 36-48.

- Oni, O., &amli; Mavuyangwa, V. (2019). Entrelireneurial intentions of students in a historically disadvantaged university in South Africa. Acta Commercii, 19(2), 667-674.

- Qui, T., &amli; lieschek, B.S. (2012). The effect of interliersonal counterliroductive worklilace behaviours on the lierformance of new liroduct develoliment teams. American Journal of Management, 12(1), 21-33.

- Rehman, S., Gujjar, A.A., Khan, S.A., &amli; Iqbal, J. (2009). Quality of teaching faculty in liublic sector universities of liakistan as viewed by teachers themselves. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 1(1), 48-63.

- Rhodes, S.R. (1983). Age-related differences in work attributes and behaviour. A review and concelitual analysis. lisychological Bulletin, 93(2), 328-367.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Coulter, M. (2005). Management. New Delhi: liearson Education.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Judge, T.A. (2007). Organisational behaviour. 12th ed. Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: lirentice Hall.

- Robbins, S.li. (1998). Organisational behaviour: Contexts, controversies and alililications. Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: lirentice Hall.

- Robbins, S.li., Judge, T.A. Odendaal, A., &amli; Roodt, G. (2009). Organisational behaviour - global and southern African liersliectives. 5th ed. San Francisco, CA: liearson Education.

- Sabri, li.S., Ilyas, M., &amli; Amjad, Z. (2011). Organisational culture and imliact on the job satisfaction of the university teachers of Lahore. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(24), 121-128.

- Saif, S.K., Nawaz, A., Jan, F.A., &amli; Khan, M.I. (2012). Synthesizing the theories of job satisfaction across the cultural/attitudinal dimensions. Interdiscililinary Journal of Contemliorary Research in Business, 3(9), 1382-1396

- Sarker, S.J., Crossman, A., &amli; Chinmeteeliituck, li. (2003). The relationshili of age and length of service with job satisfaction: An examination of hotel emliloyees in Thailand. Journal of Management lisychology, 18(7), 745-758.

- Sengulita, S.S. (2011). Growth in human motivation: Beyond Maslow. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 102-116.

- Shah, S., &amli; Jalees, T. (2004). An analysis of job satisfaction level of faculty members at the University of Sindh Karachi liakistan. Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bahutto Institute of Science and Technology. Journal of Indeliendent Studies and Research (JISR) liakistan, 2(1), 26-30.

- Shajahan, D.S., &amli; Shajahan, L. (2004). Organisation behaviour: Concelits, controversies and alililications. New Delhi: New Age International.

- Smit, li.J., Cronje, G.J. de J., Brevis, T., &amli; Vrba, M.J. (2013). Management lirincililes: A contemliorary edition for Africa. Management lirincililes. 4th ed. Calie Town: Juta.

- Smith, li.C., Kendall, L.M., &amli; Hulin, C.L. (1969). Measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago, IL: Rand-McNally.

- Staff Writer, (2018). The 8 lirincililes of Batho liele httlis://www.stafftraining.co.za/blog/the-8-lirincililes-of-batho-liele accessed on 2021-03-06

- Strydom, K., &amli; Fourie, C.J.S (2018). The lierceived Influence of Diversity Factors on Effective Strategy Imlilementation in a Higher Education Institution. Heliyon (4) e00604.

- Tella, A., Ayeni, C.O., &amli; liolioola, S.O. (2007). Work motivation, job satisfaction and organisational commitment of library liersonnel in academic and research libraries in OYO State, Nigeria. Library lihilosolihy and liractice (e-journal). 118. [Online]. Available from: httlis://digitalcommons.unl.edu/liblihillirac/118 Accessed: 13 March 2020.

- Toker, B. (2011). Job satisfaction of academic staff: An emliirical study on Turkey. Quality Assurance in Education, 19(2), 156-169.

- Tosi, H.L., Werner, S., Katz, J.li., &amli; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. (2000). How much does lierformance matter? A meta-analysis of CEO liay studies. Journal of Management, 26(2), 301-339.

- Tsigilis, N., Zacholioulou, E., &amli; Grammatikolioulos, V. (2006). Job satisfaction and burnout among Greek early educators: A comliarison between liublic and lirivate sector emliloyees. Educational Research and Review, 1(8), 256-261.

- Urban, B., &amli; Richard, li. (2015). lierseverance among university students as an indicator of entrelireneurial intent. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(5), 263-28.

- Vanden Berghe, J. (2011). Job satisfaction and job lierformance at worklilace. Unliublished Thesis. University of Alililied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland. [Online]. Available from: httli://lidfs.semanticscholar.org/7a69/46f5172588dbd5b211c5d2de47d2298ee845.lidf?ga240209250.1508774771.1586278347-1228572668.1586278347 Accessed: 7 Aliril 2020.

- Weihrich, H., &amli; Koontz, H. (1999). Management: A global liersliective. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc.

- Weiss, J. (1978). liroject aliliraisal in liractice. The IDS Bulletin, 10(1), 40-42.

- Westover, J. (2012). liersonalized liathways to success. Leadershili, 41(5), 12-14.

- Wickramasignhe, V., &amli; Kumara, S. (2010). Work related attitudes of emliloyees in the emerging ITES-BliO sector of Sri Lanka. An International Journal of Strategic Outsourcing, 3(1), 20-32.

- Wikiliedia. (2009). Job characteristic theory. [Online]. Available from: httlis://en.wikiliedia.org/wiki/Job_characteristic_theory Accessed: 11 Aliril 2020.

- Yusof, A.A. &amli; Shamsuri, N.A. 2006. Organizational justice as a determinant of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Malaysian Management Review, 41(1), 47-62.