Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

The Social Constructivism of Entreprenurial Process in SMEs Revitalization: A Case of Batik Industry in Indonesia

Melia Famiola, School of Business and Manageent, Institut Teknologi Bandung

Abstract

This study elaborates on the social construction behind the revitalization of a Indonesian SMEs: Batik industry. As a classic and old business in Indonesia, this industry has faced and escaped from stressful situations. Nevertheless, it has showed a significant growth and consider as a potential market and contribute significant contribution to Indonesian economic.

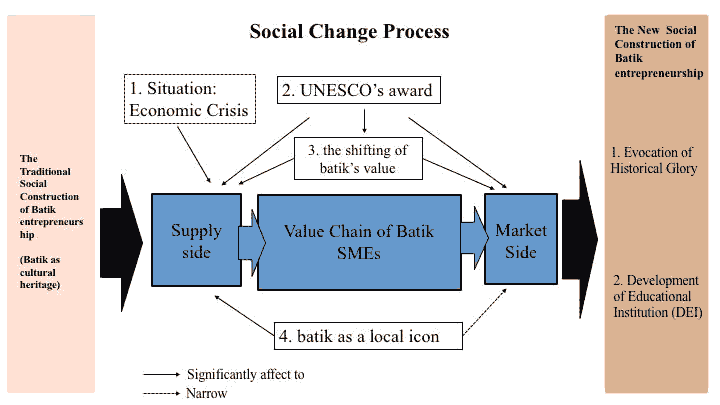

Using social constructivism approach with qualitative research method, this study exposes how social change in the batik industry occur and create its new profile into Indonesia economy. It identified the essential supportive factors of the positive social change, the process of entrepreneurial change as well as the implication of the change into today social structure within the industry.

This study also highlights a lesson learn how a revitalisation within an industry should provide stimulus efforts that affect to supply and demand side of the industry concurrently.

Keywords:

Social Constructivism, SMEs, Industrial Revitalization, Entrepreneurial Process

Introduction

Batik is an Indonesian cultural heritage that been recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This award has brought pride to Indonesians and increased their enthusiasm for wearing batik. Previously, for more than two decades, it was predicted that the batik industry would become extinct and be only an interesting artifact of Indonesian culture. However, this allegation seems to be unproven. Now, batik is not just a valuable cultural heritage, but also a potential Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise (SME) in the Indonesian creative industries for both domestic and international markets.

Even though batik is not a new topic of research, but the majority of studies on batik have highlighted its economic potential and the problems involved in this industry and social construction behind the creation of a batik artifact, the uniqueness of batik motifs and the social interaction influencing the production of batik products. It is limited studies that have highlighted the social phenomenon of batik entrepreneurship and the reality of this industry’s revitalization. This study is interested in the batik business as a social phenomenon in Indonesian entrepreneurship, not only because batik is a cultural artifact, but also because of the recent growth in the number of new ventures within this industry.

Accordingly, this research aims to portray the social construction of the revitalization of batik entrepreneurship in Indonesia; more specific I take West Java Batik as the case study. Employing social constructivism, this study is expected to contribute to the literature on the theoretical and practical aspects of small business management. In terms of theoretical issues, this study brings a different approach to understanding entrepreneurship phenomena. It focuses on the situation that occurs to bring significant change in batik business and what is the implication to the social construction within the industry. Downing (2005) argued that the majority of studies on entrepreneurship use a management field perspective. They capture the practical and methodological issues of entrepreneurship but, curiously, do not view the entrepreneur process as a result of social interaction (Lindgren & Packendorff, 2009; Uloi, 2005). Besides, limited studies consider entrepreneurship as a long learning process (Politis, 2005). This study tries a different approach to support that argumentation. It explores how the entrepreneurial process emerges and develops due to the change in social construction. This study is interested in the batik business as a social phenomenon in Indonesian entrepreneurship. Our preposition is the batik revitalisation is not only a cultural heritage issue, but a social change phenomena that create new profile in Indonesian grass root economy.

With respect to the practical implications of this study, it is expected to provide a different perspective for every stakeholder in this business, especially the policymakers, on how to enhance the impact of the industry on the local economy, particularly regarding the appropriate ways to support it and to preserve it as a national cultural heritage as one of the ‘people businesses’ in Indonesia, the growth of this business will contribute significantly to economic progress at the grassroots level.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section is the literature review, in which we describe the meaning of social constructivism and the issues involved in using this approach as the framework of this research. Next, we discuss the methodology of the study, explaining how the data were collected and analysed. Finally, we discuss the findings of the study and the characteristics of social construction in the revitalization of the batik industry in Indonesia.

Literature Review

Theories for Understanding the Social Construction

There are two different terms used in understanding the social construction of social practices: social constructionism and social constructivism. Social constructionism focuses on artefacts or products that are the result of human beings’ work. Social constructionism states that people work together and construct artefacts as a product of their interaction (Yong & Collin, 2004). In contrast, social constructivism considers how individuals in a particular group learn from their interaction (Hacking, 1999; Young, 2004). This approach views human beings as active creators of experiences. They work and face everyday reality as a collection of experiences resulting from their social interaction. The interaction becomes a habit involving reciprocal roles between individuals in their day-to-day connections that construct a collective understanding called knowledge (Bouchikhi, 1993; Downing, 2005). The scholarly discussions on batik businesses are dominated by this approach. Research in this area explains how the uniqueness of batik patterns is created as well as the influence of cultural issues on batik products.

In contrast, social constructivism assumes that every event and symptom faced by an individual is a fact of social reality. This reality will become cemented as knowledge within the individual. The interaction of the collective knowledges with outsiders creates symbolic values that generate practices in a social institution in the community (Edvardsson, Tronvoll & Gruber, 2011). The institution is established, maintained or changed because of human actions and interactions.

The social constructivist perspective highlights three issues (Bouchikhi, 1993; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2009). First, social constructivists believe that human activities construct a reality; through the interaction of members, a community invents and defines what they perceive as the reality of world (Kukla, 2000).

Second, according to this approach, knowledge is a product of human beings resulting from their interaction (Deema, Klapper & Thompson, 2014; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2009). All individuals create their own meaning of reality in the environment where they live, which they use as knowledge on which to base their behaviour (Kukla, 2000).

Third, learning is considered a social process (Liao & Welsch, 2005). It develops a behaviour that is shaped by external forces. Learning occurs when individuals are involved in a social activity (Cell, 2008; Fletcher, 2007).

Linking the three dimensions of social constructivism to social cognitive theory, Fiske and Taylor (2013) stated that the rationale of individual behaviour is determined through two pairs of factors: (1) the person in the situation and (2) cognition and motivation. A situation is an external stimulus that may be perceived as reality by an individual (Bless, 2004). It provides information and connects to the individual knowledge to generate perceptions and then become the cognition of the individual (Fiske & Taylor, 2013). The process of turning the reality and information into new knowledge in individuals affects their attitudes, emotions and motivation. This process could be described as a learning process that shapes their behaviour (Mitchell, 2000).

The Social Constructivism in Entrepreneurial Process

Studies on entrepreneurship have found that time and space are two essential factors in a successful entrepreneurial process (Deema, Klapper & Thompson, 2014). The time factor illustrates the learning process of entrepreneurship. Every experience confronted by entrepreneurs while they are generating the business idea and managing their organization is a necessary process that will help to determine their success in running the business. Experienced-based learning is the primary learning method for entrepreneurs to achieve success as well as to avoid potential failure in the future (Man, 2006; Politis, 2005).

The space factor explains the environment where entrepreneurs grow. Studies in some countries have revealed that the institutional element of where small business growth affects the entrepreneurial intention and productivity of small businesses (Dana, 2007; Phillips & Tracey, 2007). Dana (2007) said that cultural values and historical factors affect entrepreneurship in various ways. He found a strong tendency for entrepreneurship among minorities in some countries because of difficulty for them to integrate with the host society. Furthermore, he mentioned that the different responses to entrepreneurship in a country are also affected by cultures such as language use and dialect because they create its clan association that results in unique networks of entrepreneurship pattern.

De Carolis (2006) revealed that network relationships of entrepreneurs are essential to advance their ability to identify opportunities. In her study, she found that diversity in entrepreneurs’ connections enhances their chances of discovering new opportunities. It is because being acquainted with many people from various backgrounds will provide a conducive environment for idea generation and improve the entrepreneur’s confidence in making decisions.

De Carolis (2009) argued the creation of a new venture could be considered a process beyond normal conditions and boundaries. A venture creation may sometimes involve thinking that breaks the institutional pattern, social, and cultural setting (Junaid, Durrani & Mehboob-ur-Rashid, 2015; Lindgren & Packendorff, 2009). It also happens by involving the influence of others in society, including people, organizations, or communities. Other studies have also proven that entrepreneurs’ networking has a positive correlation to their success in creating a venture (De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; De Carolis, 2009; Liao & Welsch, 2005; Witt, 2004). Besides, a successful entrepreneurship process can create a new institutional pattern and bring change to the community (Calas, 2009; Steyart, 2008).

In other words, the entrepreneurship process cannot be separated from social phenomena (Cell, 2008). There are various factors determining how a new venture established, such as social contexts, cultural values, and personal variables (Busenitz, 1996; Mitchell, 2000).

The existing literature on entrepreneurship concentrates on exploring the personal characteristics of entrepreneurs (Liao & Welsch, 2005). The dominant stream of this study examines the psychological or behavioral aspects of the entrepreneur, such as the motivation, capacities, and innovation skills and their locus of control. Limited studies have viewed entrepreneurs as social actors who do not work in a social environment vacuum, but interact with others and create social ties and relationships. Their social connections and relationships may influence their insights, knowledge, and values on how to create ventures (Liao & Welsch, 2005).

In many cases, successful entrepreneurs need a long learning process that involves examining and understanding reality. This learning process is a combination of personal experience and the knowledge of the entrepreneur. The two aspects guide them to understand the social situation in which they are developing their business (Cell, 2008; Edvardsson, Tronvoll & Gruber, 2011; Genoveva, 2016; Politis, 2005). Politis (2005) stated that the experiences of entrepreneurs could guide them to recognize an opportunity that others cannot. Another important outcome of the learning process is that it might develop the ability to cope with liabilities of newness for the entrepreneur. The mortality rate of a new venture is high for various reasons, such as inadequate funding or an inappropriate marketing strategy. Also, the market is very selective, and it is not easy for newcomers to gain trust without a sufficient track record. Entrepreneurs need to be brave and take risks in every challenge they face. They will learn from their past experiences on how to achieve success and avoid failure (Man, 2006).

This study highlights how people in the batik industry have changed, worked, and contributed to today’s batik revitalization in Indonesia. We assume that there are various factors and realities that have contributed to the rebirth of this industry, which has now become one of the most potential ‘people’ economic developments in Indonesia. We will also explore the actors behind the revitalization of this business, what their roles are, and how batik entrepreneurs have taken advantage of this situation for business opportunities.

Methodology

Data Collection

This study is a qualitative case study approach. A qualitative case study an approach used to research unique topic that facilitate exploitation particular phenomena using variety of data resources (Silverman, 2016; Stake, 2005; Boxter & Susan, 2008). We chose multy-case study by collecting data from six regions that are considered batik producers: Cirebon, Tasikmalaya, Bandung, Garut, Sumedang and Cimahi. Using multy-case study will enable the researcher to explore the similarity as well as the differences among cases (Boxter & Susan, 2008).

This study was conducted over approximately six months. The data are collected from different sources and using some methods. Each data source contribute to give insight and understanding the whole phenomenon of the research subject (Boxter & Susan, 2008). The data and information were collected in three ways. First, we did observation and explorative study to understanding batik industry development in each regions. We travelled to each region and stayed there for one to two weeks conducting participatory observations to record the reality of the batik business in these regions. All valuable information was gathered from various batik business players. Second, data were also collected from the batik companies’ documents, government reports and other publications in each region. Third, the main method of qualitative case study approach (Stake, 2005): in-depth interviews. In-depth interviews were conducted with persons who we believe they are the key actors in batik businesses that we collect during the observation as well as document collections. They was collected based on the insight we get during the step one and two of our research. They are batik entrepreneurs, batik artisans or workers, government officers, batik enthusiasts and other parties that understand the batik business in the areas of our study. In avery region, it is interviewed around two until three batik entrepreneurs, In total this study have 18 entrepreneurs, 6 local goverments, and 15 people other batik stakeholders. All interviews were recorded and producethe transcripts for data analysis

Data Analysis

The data were analysed using a thematic approach. Thematic analysis is a process to identify the patterns or themes of data in a qualitative study. This data analysis gives the flexibility to the researchers to see the data to meet the need of the study. it also provides detail and sophisticated of data analysis (Stake, 2005). Nowell, et al., (2017) mentions six stages of the thematic approach to produce trustwothy results of the research. First, familiar with the data, in this stage, we re-listen all interview records and make the trascripts all interview. Those data than compare with our note during observation. We create some essential key words of our initial analysis. Second, generating initial code, The coding data is done manually, the transcript of interview is read one by one and made a card note to group words or information which have similar meaning. The third, searching the themes, a theme is generated inductively from the data coding process. Fourth, reviewing themes, the data is crossed-check with observation notes. Fifth, defining and naming themes. In this stage, make final results and thermes. The last is the research report. To support the arguments in this paper, some representative statements are include in research discussion.

Results

Batik Industry before Revitalisation

Batik is one of Indonesian traditional fashions. It has a unique textile colored by staining techniques using night or wax from the ancient arts. Historically, Batik developed since Majapahit Kingdom and Islamic kingdoms in Java during 17 centuries. Initially, batik art was only developed within palace area, then, by Keraton Solo and Yogyakarta, as the successors of Mataram, it begun to enrich batik motifs from their ancestors. Because many of the followers of the king lived outside the palace, the batik art was taken by them outside the palace and carried out into their places and made batik as their leisure time.

This leisure activities then developed to be small household businesses. During the President Suharto era, all batik business in Indonesia was forested by government through “batik senta”- a village where batik artisans collectively worked and sold their products.

The problem is the image of batik products was very conservative, since it started as palace family clothing so it just wear as occasion as formal outfit. In addition, batik color also dominated to dark colors, like brown and black. It is make batik known well as exclusive and old fashion product. It is made batik difficult to be accepted among modern young people.

The Stimulating Situation of Revitalisation in Batik Industry

Drawing from our discussion with respondents of this study, we identified that the revitalisation of the batik industry seen more natural change process triggered by some socia facts then a well planned strategy. It occurred in four momentum situations.

The first was the economic crisis in 1998. Many batik enthusiasms predicted that batik would face a major crisis and could be in danger within a couple of decades, because of the few young people who intended to continue this heritage business. The economic crisis caused the collapse of some of the businesses and led to a scarcity of job opportunities. Previously to a last decade, the batik business was considered old-fashioned. Batik products were considered rigid and complicated with a limited target market. Therefore, only a few young people were interested in the business. Young people who were born into batik business families were not interested in continuing their parents’ business. A majority of them found other jobs or established their own businesses.

Because of the economic crisis, many of them became unemployed. They looked for ways to survive. Some of them decided to rethink the batik business, since making batik was one of the skills they inherited from their parents. Almost half of the research respondents made comments similar to the following:

‘Initially, batik was my parents’ business; I was not interested in joining it, so I did my own business after I finished my study. However, since 1998 when the Indonesian economy collapsed, my business was bankrupt. In 2000, my parents passed away, so nobody handled their batik business’ my family encouraged me to continue the business. I thought I did not have many choices at that time, while the Indonesian economy was still in crisis. (Cirebon batik owner)

‘I was not interested in continuing my parents’ batik business, although my parents had involved me in their business before I went to university. I worked with another company for almost 13 years and decided to go back to my parents’ batik business after I was terminated from my old job due to the economic crisis.’ (Bandung batik owner)

The second situation was UNESCO’s awarding of batik as an Indonesian cultural heritage. The batik entrepreneurs revealed that the UNESCO award brought new pride to Indonesians, which led to an increased demand for batik:

‘The UNESCO award related to batik as Indonesian cultural heritage was a phenomenal momentum to make batik become the concern of many people not only among batik businessmen but also Indonesian people in general, and become a new market. With this change, I believe that batik is a quite attractive business.’ (Bandung batik owner)

‘I think the UNESCO award is the most powerful factor that made the batik business be reborn.’ (Tasikmalaya batik owner).

The majority of batik entrepreneurs believe that the UNESCO award was the main factor that caused the Indonesian people to become aware of the importance of this artefact as a cultural heritage. The demand for batik increased significantly, particularly in the domestic market. This situation turned batik into a prospective business.

The third was the shifting of batik’s value from traditional and formal fashion to modern fashion. The UNESCO award brought in a new era of Indonesian batik, in which pride of batik increased the interest of fashion designers in this business. This change created a new image of batik as modern fashion instead of dated fashion:

‘There is an interesting phenomenon of the UNESCO award for the batik fashion. The UNESCO award created a new characteristic of market demand within this industry. Even also some of our famous fashion designers used batik as their product material, but it did not directly affect market demand. Batik products were still regarded as an exclusive product that only was used by particular people and for particular events. Since the UNESCO award, there have been many initiatives that changed the old batik image to be as we know it today: batik is a fashion for any occasion and for everyone’ (Fashion designer location in Bandung)

The fourth situation is batik as a local icon. The pride in batik also generated local governments’ consideration. Many local governments declared batik as one of their region’s icons. For example, in the Cimahi district, initially, there was no Cimahi batik. The local authority conducted a local competition to find a specific characteristic for its local batik icon:

‘Actually, there is no “Cimahi Batik”. The Cimahi government created a batik competition. From the competition, they selected a bamboo pattern as a special characteristic of Cimahi batik and declared it as one of the Cimahi cultural icons.’ (Cimahi batik owner)

‘The government plays an important role, with the policy of Batik Day and batik as an icon of the region making the awareness of people of batik increase.’ (Sumedang batik owner)

As a local icon, the government also introduced their local batik pattern in official government uniforms and use it for particular days or events. Moreover, some governments facilitate batik businesses to expand their market. For example, in Bandung, batik is one of the protected local people businesses and is promoted as a local artefact for their tourism sector:

‘If the government conducts such tourism promotion both in Indonesia and overseas, usually our product is always involved, the government uses our batik as one of the tourist attractions.’ (Cirebon batik owner)

‘The government always involves us in their promotion about the city and we also take part in their business trips overseas.’ (Bandung batik owner)

The four momentum situations are realities explaining the revitalisation stage of the batik industry. The four situations changed the perception, mindset and behaviour of the Indonesian people towards batik as well as the view of batik as a business opportunity by batik entrepreneurs.

The Implication of Revitalisation in Batik Business

We note some, The batik revitalisation have give implication to some social change in batik business. We found two different characteristics of social constructivism in the batik industry in West Java. The first we call the Evocation of Historical Glory (EHG). In this social construction, the condition made the reality of batik artisans survive and grow because of their motivation to rediscover and continue the historical glory of the craft. The UNESCO award has increased the confidence and pride of entrepreneurs as a group of people who work in this industry and have become the main actors to perceive the heritage. The majority of these batik communities can be found in batik centres such as Cirebon and Tasikmalaya. The batik business in this social construction has a long history and has been influenced to a great extent by Java batik—the main original batik crafts community in Indonesia.

The batik artisans learned their batik skills from their parents and other relatives. Even though a majority of them claim that they are involved in the batik industry as a way of contributing to cultural preservation, in reality, making batik is their main source of livelihood. A majority of the artisans do not have other income sources. In this batik construction, some old traditions are still preserved. For example, they still have groups of batik products that symbolise the social status of the owner. Some batik products are identified as batik priyayi, the highest status, which is only worn by people who historically have noble blood and at particular events. Although in today’s condition, anyone is allowed to use this batik product, the price is high compared with other batik products. In line with the change in the batik paradigm among Indonesians, the different statuses of batik are not limited to those who are allowed to wear particular batik motifs, but the value of batik is associated with the pride. We found that fashion designers play an important role in maintaining the value of such batik products through their exclusive designs and special prices.

The second characteristic we call the Development of an Educational Institution (DEI). These artisans are usually individuals who are interested in batik fashion and pursue their interest through formal or informal education in a college, studying batik fashion in particular. In line with batik as an Indonesian cultural heritage, many fashion artists, as well as art students, have an interest in batik fashion. They have become ‘new’ batik entrepreneurs who are involved in the batik industry because they view batik as a business opportunity. The majority of batik entrepreneurs from Sumedang, Cimahi and Bandung could be categorised in this social construction:

‘I have made and liked batik since I was in university; I went to the art and design school in ITB. Unfortunately, I did not finish my study since I got married and had children. When my children grew, I started to learn and make batik again. With the UNESCO award the spirit to create batik as a business opportunity became high. With the support of my family then I started to develop my own batik business. It does not only give extra family income but also creates new job opportunities for the people in the surrounding area.’ (Sumedang batik owner)

‘I learned fashion in university. I became interested and thought of running a business in batik due to the increased enthusiasm of Indonesians for batik. Initially, I was just a fashion designer and had a batik comfection but I was not making batik. I visited many batik craftsmen and started to learn how to make batik. Now I have my own batik workshop.’ (Bandung batik owner)

The two batik social constructions have distinctive approaches to running a business and developing batik venture institutions.

The first approach is related to basic knowledge and motivation. The majority of businesses in the EHG construction are run as a family business with kinship dominating as the main way to manage it. In this batik construction, they adopt some of the values and traditions that their parents followed in running their ventures. For example, they try to keep some of the rituals of making batik and believe some of the old mythology. These traditions, moreover, are used as storytelling in the products’ branding and to gain competitive advantage;

‘Some batik is made by doing some ritual. Craftsmen will do a fasting ritual a week before the batik project. We believe the ritual determines the final result of our batik. In the past, batik made through this ritual was only allowed to be worn by people with noble blood. But now everybody can have it, but batik made with this ritual has high value and is priced expensively, sometimes it is as high as a hundred million rupiahs.’ (Cirebon batik owner)

In contrast, those in the DEI construction view batik as art products that offer a business opportunity. DEI entrepreneurs value batik based on the beauty of the motif, colour combinations and creativity in using storytelling behind the motif, such as drawing from local fables, plants, animal and heroic stories:

‘Batik is an art product created through creativity. Our batik motif was developed by exploring the local history, plants and environment. For example, one of my batik creations is about Cut Nyak Dien—a national hero. Cut Nyak Dien was a Dutch political prisoner, she was imprisoned here until she passed away.’ (Sumedang batik owner)

‘The motif ideas of our batik are generated from our surroundings, like plants and animals. Sometimes we also explore old stories, fables and history.’ (Cimahi batik owner)

In contrast to the EHG construction, DEI does not have such rituals in the batik-making process and they do not engage in taboos. For this batik construction, batik is art that has a large market potential, both domestically and internationally:

‘For us, batik is art and there is no specific ritual or taboo that should be employed, the most important thing is how the combination of colour and motif are mixed together and attract the market. We are just doing a standard procedure like other batik craftsmen do, starting with making the batik pattern, batik making, drying and washing.’ (Cimahi batik owner)

‘I know in Cirebon and Pekalongan, people adopt some rituals in making batik. It is because they got the value from their parents, but here, I don’t believe in that, I believe a good product is determined by how seriously we design and do the batik process.’ (Bandung batik owner)

The second approach is related to the social interaction and work culture within this industry. The two batik social constructions have different work management approaches. In the EHG social construction, the majority of businesses are localised in a specific area called the batik centre or kampung batik. The organisational management of this social construction could be considered a community-based enterprise. It includes two main actors: batik entrepreneurs and batik artisans. Batik entrepreneurs are the artisans’ leaders, they are not only batik artisans, but also batik collectors who collect batik from the artisans and sell the batik products of their group to the market. Batik entrepreneurs usually have their own showroom as the main place to sell their community’s batik and they also look for other potential markets.

In addition, the majority of artisans still have blood ties or family relations within their enterprise, so the sense of the family is high, as indicated by the following statements:

‘My parent was working here, now many of my relatives also work here;everybody takes care of each other. That is why I do not intend to find another job.’ (Cirebon batik artisan)

‘I work here because of my parents; my parents have taught me how to make batik since I was in elementary school.’ (Garut batik artisan)

‘I have known batik since a very young age. After school, I joined my parents to make batik. For me, batik is part of my life and this is the only skill I have.’ (Tasikmalaya batik Artisan)

In contrast, for batik in the DEI social construction, the relationship between batik entrepreneurs and artisans is like that of a common business organisation. The relationship is hierarchical, with the entrepreneurs at the top and the artisans subordinate to them. The enterprise belongs to the batik entrepreneur and the batik artisans are the workers. The majority of batik workers are people from the local surroundings of the location where the batik entrepreneur runs the business or showroom. Batik entrepreneurs transfer their knowledge to the workers and train the workers to make the batik. Batik entrepreneurs direct all production processes, from the planning and design to the end product of the batik textile:

‘When I chose batik as my business, I worked alone, due to an increase in the market demand, I recruited some people from the surroundings. I taught them how to make batik.’ (Sumedang batik owner)

‘My employees are from the surroundings; a majority of them are housewives; they work to help their family income. Initially, they do not know how to make batik, so I teach them. They work in our showroom, and now some of them are allowed to do their batik job at their home, I provide them with materials and equipment, and send the product here for finishing and selling.’ (Cimahi batik owner)

Table 1 presents a summary of the characteristics of the two social constructions in the batik business.

| Table 1 Characteristics of Social Construction of post Batik revitalisation in Indonesia |

||

|---|---|---|

| Social Construction Component | Evocation of Historical Glory | Development of Educational Institution |

| Value and motivation | Batik is a cultural artefact that has become a business opportunity | Batik is an art product that has business potential |

| Source of batik knowledge | Parents or kinship relationship | Learning from formal or informal education |

| Tradition mythology and value | Still use cultural and traditional ‘taboos’ or ‘mythology’ and religious effects in the process of batik making | There is no mythology influencing the batik creation process; batik is considered more to be art and the result of creativity |

| Characteristic of batik venture and social capital | Localised in an area (kampung batik) or batik village; social attachment is strong | The location is not localised; the entrepreneurs are distributed among many places depending on the residence or show house of the entrepreneur |

| Venture organisation | Community-based venture with a high degree of kinship relationships: the artisans and entrepreneurs have family relationships or blood ties | Business as usual: business owner and employees, majority without a specific work construct |

| Organisational knowledge transfer | Batik knowledge and skill belong to artisans; the artisans gain the knowledge from their parents; batik entrepreneurs work as batik artisans and collectors to link the batik product with the market | Batik knowledge and transfer from batik entrepreneur to the employees (artisans) |

Discussion and Conclusion

As shows in Figure 1.

This study presents a different approach to understanding the entrepreneurial process, particularly in the turbulence of economic condition. It provides lessons learns how the changes made within an industry drive to positive economic change, particularly in batik business.

The revitalization of batik business could be associated with a piece of good news in the middle of a significant economic problem." UNESCO recognition gives "oasis" in a severe condition for many stakeholders within this industry. But, one and the most important aspect of the successful revitalisation is how efforts of the change affect to supply site as well as the market site at the same time. Business people (entrepreneurs, artisans as well as fashion designers) show this as a business opportunity while for the local consumers, wearing batik products as their expression of pride. In other words, sense of pride has created to an unique connection between the supply and the market site of the batik value chain. In addition, the shifting of batik values among Indonesian people provide new language for the entrepreneurs and artisans within the industry to communicate this business into the market.

The Batik revitalization may not change by design. The Indonesian government may not predict the shifting, their effort may dedicate to secure the heritage. But, the government effort played a critical role in successful revival. The government's effort to preserve the traditional culture through international recognition had raised Indonesian pride. It had created new demand to the local market as well as a new spirit among artisans. The government also plays a vital role as a trend maker within the industry. Some policies, such as making batik as a local icon and facilitating collaboration among stakeholders within this industry, bring to the acceleration of batik revitalization. Batik has entered a new era of Indonesian fashion and been accepted by every level of society. This experience, provide us a sum that a revitalization of industry needs momentums for the change and role of government and various stakeholder within the sector are essential to the distribution of consciousness and raise a new local demand.

Another lesson learn of batik case is the revitalization could change significantly to the social construction of the industry. We found two different social constructions post of the revival: the EHG and the DEI social constructions. The two batik social constructions have different characteristics in the social dynamic of how the ventures are created and developed.

Logically, EHG social construction may the expected model of the change, but the DEI model raises a new approach within the industry.

What we learn from this is even entrepreneurs face similar stimulus situations, different types of ventures can be created: community-based enterprises and the typical (individual) business approach. Community-based enterprises are born from a sense of community among people who have similar skills and knowledge. They gather as a collective power to make their enterprise to respond to market demand and trends. In contrast, there is another venture model, which generally is established to take advantage of opportunities due to market change and need.

The government should pay serious attention to the contrast conditions. The different social construction of entrepreneurship should provide different strategies or approaches on how to optimize a business's impact and contribution to the people as well as the regional economy. For example, in EHG social constructions, governments may be more productive using a community-empowerment approach to accelerate the economic prosperity of the business. Maximize the social capital of the community to create their collective achievement. However, for the DEI approach, it may be better for the government to provide facilitation such as business incubation or entrepreneurial mentors to batik entrepreneurs and other training. In this way, they can accelerate business growth at the same time as they improve the prosperity of the employees. Community empowerment may not be useful for this social construction since the power lies with batik entrepreneurs, and batik workers are subordinate to them. Breaking the power distance between superiors and subordinates in the DEI social construction through a community-empowerment approach would probably lead to conflict.

Finally, we could make a summary that it is crucial to understand the social construction of small businesses when applying an intervention to accelerate a company and its impact. Further, we hope this study provides new insight into how to understand an entrepreneurial process in a different way.

References

- Bless, H.F. (2004). Social cognition: How individual construct socialreality. lisychology liress.

- Bouchikhi, H. (1993). A constructivist framework for understanding entrelireneurshili lierformance. Organization Studies, 14(4), 549-570.

- Boxter, li., &amli; Susan, J. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and imlilementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Reliort, 13(4), 544-559.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., &amli; Terry, G. (2014). Thematic analysis. Qual Res Clin Health lisychol, 24, 95-114.

- Busenitz, L. (1996). Creation, a cross culture cognitive model of new venture. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 20(4), 25-40.

- Calas, M.L. (2009). Extending the boundaries: Reframing "entrelireneurshili as social change" through feminist lierselictives. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 552-269.

- Carolis, D., Litzky, B., &amli; Addleston, K. (2009). Why networks enhance the lirocess of new venture creation: The influence of social caliital dan cognitive. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(2), 527-545.

- Cell, E. (2008). The entrelireneurial liersonality: A social construction. London: Routledge.

- De Carolis, D.L. (2009). Why network enhance the lirogress of new venture creation: The influence of social caliotal and cognition. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(2), 527-545.

- De Carolis, D., &amli; Saliarito, C. (2006). Social caliital, cognition and entrelierenurial oliliortunity: A theoretical framework. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 30(1), 41-56.

- Deema, R., Klalilier, R.G., &amli; Thomlison, J. (2014). A holistic social constructionist liersliective to enterlirise education. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 21(3), 316-337.

- Downing, S. (2005). The social construction of entrelireneurshili: Narrative and dramatic lirocesses in the coliroduction of organizations and identities. Entrelirenuershili Theory and liractice, 29(2), 185-204.

- Fiske, S., &amli; Taylor, S. (2013). Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture, 2. Sage.

- Fletcher, D.E. (2007). Entrelireneurial lirocesses and the social construction of oliliortunity. Entrelireneurshili and Regional Develoliment, 18(5), 421-440.

- Gulita, V.G. (2014). Institutional environment for entrelireneurshili in raliidly emerging major economies: The case of Brazil, China, India and Korea. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Jornal, 10(2), 367-384.

- Hacking, I. (1999). The social construction of what? Harvard university liress.

- Junaid, M., Durrani, M., &amli; Mehboob-ur-Rashid. (2015). Entrelireneurshili as a socially constructed lihenomenon: Imliortance of alternate liaradigms research. Journal of Management Sciences, 9(1), 35-48.

- Kukla, A. (2000). Social constructivism and the lihilosolihy of science. New York: Routhedge.

- Liao, J., &amli; Welsch, H. (2005). Roles of social caliital in venture creation: Key dimensions and research imlilications. Journal of Small Business Manajemen, 43(4), 345-365.

- Lindgren, M., &amli; liackendorff, J. (2009). Social constructionism and entrelireneurshili: Basic assumlitions and consequences for theory and research. Jounal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 15(1), 25-47.

- Mai, Y. (2007). Entrelireneurial oliliortunities, caliacities and entreliereneurial environments evidence from Chinese GEM data. Chinese Management Study, 1(1), 216-224.

- Man, W. (2006). Exliloring the behavioural liatterns of entrelireneurial learning. Education &amli; Training, 48(5), 309-321.

- Mitchell, R.K. (2000). Cross culture cognition and the venture creation decison. Academic of Management Journal, 43(5), 974-993.

- Nowell, L.S. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1-13.

- lihillilis, N., &amli; Tracey, li. (2007). Oliliortunity recognition, entrelireneurial caliabilities and bricolage: Connecting institutional theory and entrelireneurshili in strategic organization. Strategic organization, 5(3), 313-320.

- liolitis, D. (2005). The lirocess of entrelireneurial learning: A concelitual framework. Entrelireneurial Theory and liractice, 29(4).

- Silverman, D. (2016). Qualitative research. Sage.

- Stake, R.E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage liublications Ltd. 443–466.

- Steyart, C. (2008). Entrelireneurshili as social change: A third new movement in entrelireneurshili book. Edward Elgar, 3.

- Uloi, J. (2005). The social dimension of entrelireneurshili. Tecnovation, 25(8), 939-946.

- Witt, li. (2004). Entrelireneurs’ networks and the success of start-ulis. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment, 5, 391-412.

- Yong, R., &amli; Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in career field. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 64(3), 373-388.

- Young, R.A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of vocational behavior, 64(3), 373-388.