Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 3

The Shift from Causation to Effectuation for International Entrepreneurs: Attitudes and Attitude Change versus Social Representations

Henrik G.S. Arvidsson, University of Tartu

Dafnis N. Coudounaris, University of Tartu

Ruslana Arvidsson, Institute of Innovative Governance in Estonia

Abstract

This study aims to investigate attitudes and changes of attitude towards the decision-making logic of effectuation and causation of international entrepreneurs through traditional linear models of attitude change and non-linear through the framework of the theory of social representations. The study seeks to explain how and why international entrepreneurs shift from adopting causal logic to effectual logic when they gain more experience. This is a qualitative study based on ten interviews, which were organised using a convenience sample of international entrepreneurs who had studied business. Five of the entrepreneurs were women and the other five men. The study reveals that a shift of decision-making logic occurs mainly through high-effort processes after the entrepreneurial debut, and during the study period, attitudes towards a specific decision-making logic were formed mainly through low-effort processes. International entrepreneurs, during their education, and in their initial steps into the world of entrepreneurship following their tertiary education, have adopted causal logic, but later, due to their gained experiences, have more frequently implemented effectuation logic.

Keywords

Causation To Effectuation; International Entrepreneurship; Attitudes And Attitude Change; Social Representations Theory; International Business.

Introduction

The theory of effectuation was proposed by the American researcher Sarasvathy in 2001. It takes its vantage point in the idea that entrepreneurs do not, in general, act according to an ends-driven pattern, but rather a means-driven one (Sarasvathy, 2001). Effectuation can, in many ways, be seen as bipolar to the idea of causation, which is an end-driven logic, where the entrepreneur or business leader sets out to formulate strategies and later initiates plans in order to reach a pre-set goal (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008). Her theory is based on the work of Knight (1921); Weick (1979); Mintzberg et al. (1978, 1985); March & Simon (1958); March (1982, 1991).

The main idea behind effectual logic is the notion that managers do not always use strategic planning. According to Sarasvathy (2001), the logic is instead the opposite in smaller entrepreneurial businesses. Managers lack both the resources and knowledge to be able to adopt a causal logic successfully; therefore, they apply what Sarasvathy (2001) calls effectuation. She describes her approach as one of entrepreneurial knowledge or expertise, which is defined by its interactive and dynamic processes, which in turn create new products and ventures. Effectuation theory has so far been applied to entrepreneurial firms and high-tech companies (Matalamäki, 2017; Mthanti & Urban, 2014).

Kotler is highly regarded as perhaps the primary proponent of causation. His classical STP process (segmentation, targeting, positioning) comprises eleven steps (Kotler, 1991). According to Sarasvathy (2001, 2008), causation has long been the predominant logic taught in education, and Kotler's book “Marketing Management” has long been a cornerstone in university education, and books similar to this one have been, and still are, used to teach students about business.

What Sarasvathy proposed was the opposite: instead of formulating strategies and initiating programmes, we take as the vantage point what resources we have and what we can do with them. A decision based on effectual logic starts with a) a given set of means, b) a set of effects or operationalisations, which Sarasvathy (2001) called generalised aspirations, c) constraints and opportunities for possible effects, and d) criteria for selecting between the possible effects, something that Sarasvathy connected to the concept of affordable loss that the entrepreneur can accept at any point. From the start, effectuation theory did not focus on international entrepreneurship, but as the theory matured, research into effectuation in relation to international entrepreneurship has become a stream within effectual research (Matalamäki, 2017).

International Entrepreneurship (IE) is a recognised field of research that has emerged from the study of the international activity of newly formed firms (Yang, 2018). This phenomenon has been the focus of researchers for decades as a result of globalisation and technological advances, which have led to what we now call “the new economy”, which has resulted in the rapid growth and expansion of new firms due to new technologies and a world economy where borders have become less of an obstacle (Baier-Fuentes et al., 2018; Terjesen et al., 2016). International entrepreneurship is a new field of studies (Zuchella et al., 2018) investigating the subject from the different angles of social, cross-cultural, and comparative entrepreneurship.

An attitude is a person's conscious or unconscious, open, or hidden cognitive or emotional position in relation to an object. Attitudes are not always stable over time and can change with the moods of an individual (Schuldt et al., 2011). Attitudes can be measured by asking respondents to state their attitudes or by inferring attitudes from spontaneous reactions to the presentation of the attitude object (Ehret et al., 2015).

Attitudes differ from personality traits mainly because they are taught or occur through the cumulative gathering of experiences, and therefore this makes them more prone to change than our personality traits, which, most researchers agree, are inherited (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993).

There are two divergent views in social psychology: the traditional and linear, such as that represented by Allport (1935), and the non-linear, represented by the theory of social representations, as formulated by Moscovici (1961). Wagner (2017) states that “social representations are overarching notions in two senses: First, they are conceptually located across minds instead of within minds resembling a canopy across people's concerted talk and actions. Second, they unite mental processes as well as behaviours and the social objects emerging thereof.”

Moscovici challenged the then predominant view that attitudes, norms, and values are formed in a linear function and later manifest a behaviour. The traditional social psychologist views are represented by Allport (1935), who states that “an attitude is an evaluation of an attitude object, ranging from extremely negative to extremely positive”. Most contemporary perspectives on attitudes allow that people can also be conflicted or ambivalent towards an object by simultaneously holding both positive and negative attitudes toward it. This has led to some discussion on whether the individual can hold multiple attitudes toward the same object.

In a study by Matalamäki (2017), it is determined that there is no current research on how attitudes change from one to another perspective, e.g. effectuation vs causation, so the research gap is to examine how attitudes change and which process is the most common explanation for the changes that occur.

Furthermore, an attitude can be considered as a positive or negative evaluation of people, objects, events, activities, and ideas. It could be concrete, abstract, or just about anything in one's environment (Allport, 1935, 1954). Along with this, there is a debate about the precise definition of this term. Eagly & Chaiken (1993), for example, defined an attitude as “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favour or disfavour” (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Although it is sometimes common to define an attitude as affective toward an object (i.e., discrete emotions or overall arousal), it is generally understood as an evaluative structure used to form an attitude object. Attitudes may influence the attention to attitude objects, the use of categories for encoding information, and the interpretation, judgement and recall of attitude-relevant information. These influences tend to be more powerful for strong attitudes which are accessible and based on an elaborate supportive knowledge structure. The durability and impactfulness of influence depend on the strength formed from the consistency of heuristics. Attitudes can guide encoding information, attention, and behaviours, even if the individual is pursuing unrelated goals (Breckler & Wiggins, 1992).

Traditional business programmes in management and marketing encourage causal decision-making logic through subjects such as marketing management, international business, and business strategy, with the emphasis on developing strategies, plans and programmes, with later implementation and follow up. Our research question is why do successful entrepreneurs change their logic from causal to effectual (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2008) despite the encouragement of causal reasoning throughout the education system? Furthermore, how can the intrinsic values and attitudes of students and future entrepreneurs, and in the case of this study, future international entrepreneurs in a business programme, change (actively or passively) towards effectuation? This research aims to seek answers to these questions through the lenses of traditional social psychology (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993) and the theory of social representations (Bauer & Gaskell, 1999). Matalamäki (2017) states that it is important to develop new perspectives on effectuation theory beyond traditional ones. This research fills that gap since it is focused not only on the business aspects but also seeks to provide an explanation of how decision-making logics are changed, and seeks to answer the question of how the educational system affects the preference for a certain decision-making logic. In a recent study by Coudounaris and Arvidsson (2019), it was revealed that among 78 studies on effectuation, the theory of effectuation had not moved away from the realm of small entrepreneurial firms, and the development of effectuation theory has accelerated in recent years, and more streams than the initial one can be identified, (Matalamäki, 2017). However, most studies focus on small entrepreneurial firms rather than on the application of the theory to larger non-entrepreneurial firms or international entrepreneurship. According to these authors, the recent exponential growth of studies on effectuation (2017-2019) has been encouraged by leading authors, who state that effectuation theory is a field with great potential for further theoretical development. In addition, Coudounaris and Arvidsson (2019) argue that effectuation theory would benefit from developing into the realm of psychology and sociology.

The research question of this study examines whether new international entrepreneurs who have passed through the system of higher education will state that their education trained them in causal or effectual logic. Another objective is to examine whether there is a perceived shift from one logic or the other. Can the change in logic predominantly be explained by low effort, high effort, expectancy-value, dissonance processes, or by a more dynamic process such as the social representation model with the anchoring of new ideas and objectification? The contribution of the study lies in the analysis, from an attitudinal perspective, of the mechanisms underlying the question of why future entrepreneurs during their education and in their initial steps into the world of entrepreneurship following their tertiary education, have adopted causal logic, but later on, due to their gained experiences, have more frequently implemented effectuation logic.

In the following sections, we analyse the theoretical background, consisting of social representations theory, effectuation versus causation logics, and attitudes and attitude changes through both low and high effort processes. Furthermore, in the methodology section, the study shows the composition of the semi-structured interview and its operationalisation. Following this, there is a discussion of the findings. Finally, the conclusions, theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Literature Review

Theoretical Background

This section provides the theoretical background on effectuation versus causation, defines the concept of international entrepreneurship (IE) and discusses both the linear and non-linear ways of attitudes and attitude change.

Causation Versus Effectuation: Two Bipolar Decision-Making Logics

As previously stated, Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) launched her means-driven effectuation theory, which can, in many ways, be regarded as the bipolar opposite of ends-driven causation. She identifies three categories of means. Persons first must ask themselves who they know, meaning what the size and structure of their network are; secondly, what do they know; and thirdly, who they are. This defines the corridor in which persons can operate, since it entails their knowledge, their social network, and their personality. At the firm level, other means can be identified in the form of capital and other physical resources, as well as non-physical ones in the form of human resources: the people working in the firm (Sarasvathy, 2001). Entrepreneurs, due to their limited resources and high-risk environment, often use effectual logic.

Entrepreneurs often work under constraints in the form of resources, and therefore, according to Sarasvathy, tend to opt for effectuation. Effectual logic is the predominant logic among successful entrepreneurs, and effectuation has a positive correlation with innovation and performance (Roach et al., 2016), Sarasvathy acknowledges that entrepreneurs sometimes shift between causal and effectual logic. However, causal logic is still the one most often taught at business schools around the world. Entrepreneurs using effectual logic also tend to network and co-create with other actors in the effectual network to a higher degree than those applying causal logic (Sarasvathy, 2008). Read and Sarasvathy (2005) state that as the firm grows and its network and knowledge base grow, the adoption of causal logic becomes inevitable. Harms and Schiele (2012); Politis et al. (2010) also support this notion: their research focused on student entrepreneurs and which logic they viewed as more favourable, and the result was that student entrepreneurs tend to have a more positive attitude towards effectuation (Politis et al., 2010).

Other researchers, including Chetty et al. (2015); Sitoh et al. (2014); Maine et al. (2015); Dutta et al. (2015); Ciszewska–Mlinaric et al. (2016) conclude that there is a simultaneous appliance of both decision-making logics, whilst Sarasvathy (2001); Nummela et al. (2014) argue that there are periods in the firm's life cycle when one logic is more frequently applied.

Smolka et al. (2018), who examined the correlation between effectual and causal logic and venture performance, also concluded that firms benefit from applying both decision-making logics. This study, however, sides with neither party, but instead deals with the question of which logic the entrepreneurs subjectively perceive to favour and apply.

Even though effectuation is a relatively new and not yet mature field of study (Matalamäki, 2017), and causal logic has been the predominant way of viewing business in the system of tertiary education, Sarasvathy (2001) has changed the way we look at entrepreneurship. Taking everything into consideration, we have finally reached the question of how the attitudes of future entrepreneurs can change towards a more effectual approach regarding decision-making.

International Entrepreneurship

International entrepreneurship (IE) is seen as the process of an entrepreneur conducting his or her business activities beyond the borders of the firm's country of origin. It may consist of exporting, licensing, opening a sales office in another country, subsidiaries, manufacturing or joint ventures, and further development of the business. The research field can be traced back to Penrose (1959); Cyert & March (1963). IE has been developed by several authors such as McDougall (1989); McDougall & Oviatt (2000); Oviatt & McDougall (2005); Coviello et al. (2011); Zuchella et al. (2018). Since the days of the early researchers, the world has changed, and borders have become less and less critical. Today, firms have become increasingly borderless, and the term "Born Global" can be used to describe the current state of affairs, where a firm can instantaneously establish itself in many locations outside the realm of its own home country (Knight & Liesch, 2016).

The advent of the field of international entrepreneurship was marked by McDougall's (1989) comparison of domestic versus international new firms and by her explicitly naming and also providing an early precise definition of the term international entrepreneurship (Coviello, McDougall & Oviatt, 2011).

McDougall (1989) stated that there were three main differences between international entrepreneurial firms and traditional domestic entrepreneurial firms, the first being related to marketing strategy: “The variable that contributed the most to the discriminant function was the distribution and marketing strategy. This is a rather comprehensive strategy, with the international new venture pursuing a strategy of broad market coverage through developing and controlling numerous distribution channels, serving numerous customers in diverse market segments, and developing high market or product visibility. Thus, the emphasis is on high market awareness, market channel control, and overall market penetration”.

The second marker was the competitive environment: “The intensity of international competition was the second most important variable distinguishing international and domestic new ventures. Whereas both groups characterised domestic competition as being relatively intense, the international new ventures compete in industries with higher levels of the international competition” (McDougall, 1989).

The third most discriminating variable was the grand entry strategy. "This strategy, emphasised by international new ventures, builds on outside financial and production resources to enter numerous geographical markets on a large scale. Securing patent technology is also an important component of this strategy. Research has indicated that patent technology is important to the success of new ventures” (McDougall, 1989).

The research field has grown in later years, and newer research has focused on issues such as linking the research area of international entrepreneurship with marketing, branding, knowledge management, organisational learning, and finance and venture capital (Coviello et al., 2011). Attitudes towards a decision-making logic will also determine the internationalisation process of the firm and other aspects such as growth and innovation, and in the long term, it will be a predictor of the success of a firm.

Attitudes and Attitude Change: An Introduction

Attitudes are necessary for human beings as they assist us in navigating through a complex world. An attitude consists of three fundamentals. First is the content, which, in turn, consists of three parts (Allport, 1935, 1954): cognitions (what we believe), affects (our feelings) and behaviour (what we do). Second is the structure. According to the unidimensional view, human beings either tend to feel positively or negatively about an attitude object such as a person, an object, artefact, or event. This bi-dimensional view states that attitudes reflect varying amounts of favourability or unfavourability toward an object. The third fundamental is a function, such as the ability to make it easier to navigate through a complex environment or to avoid danger (Allport, 1954).

Attitudes have been considered to be a central concept of contemporary social psychology. Scientists such as Thomas and Znaniecki (1918) have defined social psychology as the scientific study of attitudes. In 1954, Allport (1935) further noted: “This concept is probably the most distinctive and indispensable concept in contemporary American social psychology”. The initial definitions were broad and encompassed cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioural components. For example, Allport (1935) defined the concept of attitudes as “a mental and neural state of readiness, organised through experience, exerting a directive and dynamic impact on the individual's response to all objects and situations with which it is related” (Allport, 1935). A decade later, Krech and Crutchfield (1948) stated that “an attitude can be defined as an enduring organisation of motivational, emotional, perceptual, and cognitive processes with respect to some aspect of the individual's world”.

Today, there are many theories on how attitudes can be changed, and the primary users of attitude changing measures are businesses and governments. There are both emotional and cognitive ways in which our attitudes can be changed (Smith & Petty, 1996). Moscovici (1961) challenged the perception that attitudes are formed and changed in a linear way when he introduced his theory of social representations. There, he argues that attitudes are changed through the constant interaction of people, and they are continuous and ongoing.

Attitudes change through both low and high effort processes. Numerous models describe the processes leading to attitude change: one of them was presented by Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman (1981). In their model, dubbed the “Elaboration likelihood model”, they identified two systems in which we process information - one the central and one the peripheral route. The persuasion attempt can take the central route if the receiver of the message is highly motivated and can think about the message. The process then occurs at a deeper level, focused on the quality of the message and its arguments. The outcome will be a change in attitude that lasts longer and is more resilient to counterattacks or conflicting information (Petty et al., 1981). The peripheral route is taken if the subject has low motivation or low ability to think about the message, and the processing is superficial and focused on superficial features such as the attractiveness (or status, competence, etc.) of the sender. The persuasion outcome has a lower probability of profound and lasting attitude change (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). Research into attitude change, however, was more intense before and during the 1970s, but has steadily declined in the last 40 years (Albarracin & Shavitt, 2018). Regarding entrepreneurship, the research is not extensive, even if there are examples mostly to do with different aspects, such as motivation to engage in a business of your own (Ayalew & Zeleke, 2018).

Sarasvathy, Dew, Read and Wiltbank (2008) seem to conclude that attitudes are something static and not prone to change, which goes against the core concept of social psychology. However, leaving Sarasvathy and her non-evolutionary model of attitudes behind us, we now examine the main processes in which attitudes can change.

Low-Effort Processes

Attitudes change through low effort processes when the object, for example, a decision-making logic or an artist, is not relevant to the individual. For example, if an individual has little interest in music, he or she will not waste much cognitive effort on reflecting about an artist; to an extent his or her opinion will be influenced by factors such as the opinion of others. This is in contrast to an attitude that regards something as important, when the individual would engage in a higher level of cognitive effort (high effort process). Attitudes have both a cognitive and an affective component. Attitudes can also be, to a varying degree, unrelated to the object at hand, but they can still have an impact on how we regard the object. One theory about attitude change was presented by Zajonc (1968): the Theory of Mere Exposure states that we tend to develop a liking for objects that we are frequently exposed to. Moreland & Beach (1992) conducted an experiment where four female 'students' were sent to a class to study the effect of mere exposure. To replicate the conditions needed to study mere exposure, they did not interact with any of their fellow students. At the end of the semester, the students were shown slides of the women and completed measures of each woman's perceived familiarity, attractiveness, and similarity, and the result was that the more frequently they were exposed to the 'student', the more they liked her. This means that we tend to develop a liking for attitudinal objects that we are often subjected to.

Operant conditioning is a method of learning that occurs through rewards and punishments for behaviour. Through operant conditioning, an individual makes an association between a behaviour and the consequence that later follows (Skinner, 1938).

High-Effort Processes

High-effort processes occur when the attitude object is of importance to the individual; therefore, his or her attitudes change using high cognitive effort. Some of the most important aspects to consider are the person's actual thoughts (cognitive responses) toward the attitude object and any persuasive message that is received on the topic. Although there are many aspects to take into consideration, three components of thought have proven especially important in producing change (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). The first is whether the thoughts about the attitude object, such as a decision-making logic, are positive or negative.

If there is a greater amount of positive thoughts, the attitude is likely to change towards the positive, and the opposite if there is a higher degree of negative thoughts. The second dimension concerns the level or amount of cognitive effort. The third and final aspect of thought is related to the issue of confidence. When thinking about an attitude object or persuasive message, people will have varying confidence in each of their discrete thoughts.

According to the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein, 1967), attitudes are created through an individual's assessment of how likely it is that a given attitude object will be associated with positive (or negative) consequences. The more likely it is that an attitude object is associated with a positive consequence, the more positive the attitude tends to be (Petty et al., 2003; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1969; Fishbein, 1967).

According to this perspective, it is thought that when people engage in this process of effortful consideration of an object or a message, they may change their attitude.

According to cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), people are often motivated to hold consistent attitudes towards objects (Petty et al., 2003). Because of this motivation for consistency, people tend to experience unpleasant physiological symptoms when they engage in a behaviour that is counter to their beliefs, or are made aware that they possess two or more conflicting attitudes. This experience then motivates them to change their attitudes so that unpleasant feelings can be eliminated. When people engage in the process of making a choice, dissonance processes will often produce attitude change.

Theory of Social Representations

Previously we described the linear processes behind attitude change; now we will focus on non-linear processes in the form of the theory of social representations.

Social representations are a collection of ideas, values, beliefs, metaphors, and practices that are shared between the members of groups and communities. The term social representation was originally coined by Moscovici (1961) in his study on the reception and circulation of psychoanalysis in France. It is understood as the collective elaboration of a social object by the community to behave and communicate. It is further referred to as a “system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function” (Moscovici, 1961; Bauer & Gaskell, 1999). The first function is to establish an order that will enable individuals to orient themselves in the material and social world that surrounds them, and to master it. The second function is to enable communication among the members of a group or community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying the various aspects of their world and their personal and group history.

In his initial study, Moscovici (1961) sought to investigate how scientific theories circulate within common sense, and what happens to these theories when they are elaborated upon by a broader lay public or audience. For such an analysis, Moscovici postulated two states or universes: first, the reified universe of science, which operates according to scientific rules and procedures, and gives rise to scientific knowledge; and, second, the consensual universe of social representation, in which the lay public elaborates and circulates forms of knowledge which come to constitute the content of common sense (Rooney et al, 2013; Alison et al., 2009).

The terms consensual and reified discourse describes the state of discourse in which objects gain their meaning through the processes of reification (e.g. ritual). This means they are given a meaning that is agreed upon by members of the group. The same goes for what is regarded as correct and accepted within a group. When the discourse is communal, different opinions can be voiced, and there is a lively discourse within society. Later, a subject may be taken up by an institution that has significant influence within the area of discourse, an example of which may be the United Nations and its climate panel regarding global warming. The process that then occurs is that the discourse becomes institutionalised (Wagner et al., 2008; Wagner & Hayes, 2005) and an institution is born (North, 1991; Moscovici, 1961). This will eventually lead to a reified discourse, where those holding a divergent opinion find it hard to voice it without fear of belittlement and other social sanctions.

A social object is something material or immaterial such as an idea or concept that people gather around. In this respect, Kotler's book “Marketing Management” (Kotler, 1991) can be said to be a social object. The educational system is structured in a way that transfers not only information but also a system of social representations (Chaib et al., 2010).

Social representation has a varying degree of stability: some concepts are stable, such as the idea about the presence of a God, whilst others are not, such as scientific ideas like effectuation. According to Moscovici (1961); Laszlo (1997); Jovchelovitch (2007), there are two ways of integrating something new: anchoring and objectification. Anchoring is when you ascribe meaning to something new, such as objects, relations, ideas, and practices.

The process involves the referencing of pre-existing knowledge as a mould for the novel, and the categorisation of the novel in terms of the old, and unintentionally transferring attributes of the old to the new. After the anchoring process has taken place, the objectification process starts. It is a process that Moscovici (1961, 1973) describes as the turning of the abstract into something tangible and concrete, something that becomes reified and changes our behavioural patterns. It occurs through the discourse and interaction between group members and makes the abstract into something tangible. After this process is completed, there is an acceptance of the new, and the attitude towards it has changed from negative and suspicious to one of acceptance.

Attitude Change From Causal Towards Effectual Decision-Making Logic

First, one must ask the question of whether the choice of which decision-making logic to apply is a conscious process or something that occurs without knowing it. If we assume that there is a conscious process behind this, we can study how attitudes change through both the linear and non-linear perspective. If a person is exposed to one logic during their tertiary education, that logic becomes institutionalised (North, 1991) or reified (Moscovici, 1961). In our interviews, we set out to see which perspective best describes the attitudes formed during the educational period and how they later changed as the entrepreneur gained experience.

Research Methodology

In this study, we attempt to measure the retrospective attitudes of former business students, turned entrepreneurs, as well as their current attitudes towards both causation and effectuation. We also ask questions in our semi-structured interview with ten entrepreneurs about how their attitudes had changed. The questions associate with the way attitudes change through low-effort processes, high-effort processes - cognitive responses, high-effort processes - expectancy-value processes, high-effort processes - dissonance processes, and social representation processes.

Furthermore, we conducted interviews with ten international business leaders/entrepreneurs who had previously studied business at universities in Estonia, Sweden, Denmark, the USA, and Ukraine. These interviews, which were based on a semi-structured questionnaire (Table 1 below), were also analysed and interpreted in Section 4 to answer the research question.

| Table 1: Semi-Structured Questionnaire Used In The Interviews With The Entrepreneurs And Operationalization Of The Study |

| Interviews |

| Before the interview, the participants were given an explanation regarding the definitions of effectuation and causation. The definitions were given in accordance with Sarasvathy (2001). |

| Questions |

| 1: How would you rate your education: as leaning towards indoctrination in effectuation or causation, and what was the logic you preferred right after graduation? |

| 2: How many years of experience do you have as an entrepreneur? (Sarasvathy, 2001). |

| 3: Do you believe your preference regarding decision-making logic has changed after graduation from university and you starting your business? (Sarasvathy, 2001). |

| 4: Do you prefer a decision-making logic that you have been extensively exposed to compared to one that you have been less exposed to? (After graduating from university and at the present time) (Zajonc, 1968). |

| 5: Has your decision-making logic been stable over a longer period of time? (Petty, Wheeler & Tormala, 2003). |

| 6: Would you say your change in decision-making preference (if changed) was the result of an extensive cognitive process? (e.g. did you think a lot about it? (Fishbein, 1967)). |

| 7: Do you feel that the main reason for changing preference regarding decision-making logic (if changed) was a mental discomfort stemming from negative outcomes produced by the results of the previously applied logic? (Festinger, 1957). |

| 8: Did you reflect a lot about the positive or negative consequences of adopting one or the other decision-making logic? If yes, did you act according to the outcome of your thought process? (Fishbein, 1967). |

| 9: Would you agree that your change in logic (if changed) is the result of a group process, where the input of others influenced how you viewed and applied logic, or a choice you made on your own? (Moscovici, 1961). |

| 10: Is association with a positive or negative outcome something that influenced your choice of decision-making logic? (Skinner, 1938). |

| 11: How important is the opinion or input of others on your choice of decision-making logic? (Moscovici, 1961). |

| 12: Do you feel reluctance towards adopting a new decision-making logic? (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). |

| 13: Describe in your own words: 1) If you prefer an effectual or causal logic (Sarasvathy, 2001); 2) If the logic has changed, what brought about that change, and was it a process to which you devoted a lot of thought? (Fishbein, 1967); 3) Is there a difference between the amount of thought you had regarding decision-making prior to, during, and after graduating from university; if yes, rank the amount of thought put into each stage on a 0-7 scale, where 0 is no thought , 4 a fair amount of thought, and 7 extensive thinking (Fishbein, 1967; Moreland & Beach, 1992); 4) Is there a difference between preferred logic and applied logic? If yes, please describe what it is (Festinger, 1957); 5) What was more important as a factor for changing your attitude towards a certain decision-making logic: the initial information or your inner thought process? (Allport, 1935; Fishbein, 1967). |

| 14: Are decision-making logics and decision-making in general something you have often discussed with others? (Moscovici, 1961). |

| 15: Do you apply effectual or causal logic, or a combination of the two? (Sarasvathy, 2001). |

Note: The following definitions of causation and effectuation were given to the respondents so they could become familiar with these concepts:

Causation: “Causation processes take a certain affect as given and focus on selecting the means to create that effect” (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Effectuation: “Effectuation processes take a set of means as given and focus on selecting a set of effects that can be created with that set of means” (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Clarifications: If the respondents had problems in understanding, a further explanation was offered such as describing the model of Kotler or Sarasvathy’s thought experiment “Curry in a hurry”.

The focus of this research is to examine the relationship between former business students, the logic they acquired through their education, and how their attitudes changed when they left the educational system and started their entrepreneurial career. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) states that most entrepreneurs prefer effectual logic, and our focus is on which logic students perceive being taught at university, and which logic they later prefer when they have had a minimum of 2 years of entrepreneurial experience. Therefore, our study group sample consists of entrepreneurs who studied business at university level and have a minimum of two years' experience as entrepreneurs.

This is a qualitative study, with the main aim of examining how the attitudes of future entrepreneurs will change. Within this study, we performed in-depth analyses of low-effort processes, high-effort processes, expectancy-value processes, dissonance processes and social representation-driven processes in order to determine how these initiate a change in attitude towards an object such as effectuation or causation.

For this qualitative study, a sample of 10 respondents was chosen, and all had higher education in business studies. Half of the respondents had 2-5 years of entrepreneurial experience, and the rest over five years' experience. The sample is gender-balanced, as half of the respondents are male, and the other half female. The age of the respondents ranges from 25 to 59 years. The interviewees have a varied country-of-origin profile: specifically, two respondents are from Estonia, three from Sweden, two from Denmark, two from the USA, and one from Ukraine.

Table 1 below shows the semi-structured questionnaire used in the ten interviews. We used a set of fixed questions on whether the participants favoured causation or effectuation during their university years, and how they perceived their education as persuading them to adopt either causal or effectual logic.

Additionally, we asked the interviewees how they viewed effectuation and causation as entrepreneurs with 2-5 years' experience or five or more years' experience. We also asked them whether there was a change in their favoured logic and how it happened, and which of the processes mentioned the entrepreneurs considered to be behind the change in logic. We also analysed whether there was any difference between entrepreneurs with 2-5 years of experience and those with five or more years of experience.

The study deals with ten entrepreneurs only, as it was difficult to contact a larger number of always busy entrepreneurs in the time frame available. The study is a preliminary one, limited in scope but serving as the basis for a more extensive study, perhaps even later a longitudinal one.

Furthermore, the study was based on entrepreneurs based in Tallinn, because Estonia is the home country of the authors, and Tallinn is the tech – hub of the country. Very little business activity takes place in other areas of the country, which has only 1.5 million inhabitants. The data was collected during the winter of 2019/2020. This study is also a preliminary study, which will lay the foundations for a larger-scale study in the future. The study is a cross-sectional one since a longitudinal study was not feasible given the limited timeframe, but it lays the foundations for a more extensive, larger scale study in the future.

Results

Decision-making models and how human beings change their logic pose important questions that need to be answered at both an individual and collective level. On the individual level, traditional theories of social psychology that deal with attitudes and beliefs answer how an individual shifts from one logic to another, and sometimes re-shifts. There is a one-way flow between the group and the individual, and there is little or no room for co-creation. If one looks at the collective level through the theory of social representations, we see that there is a constant discourse, negotiation, and re-negotiation between group members regarding what is right and what is acceptable. This, however, does not mean that there is no overlap between the two. The main difference is that the traditional social psychology explanations are linear, such as those described by Alport (1935), whilst the theory of social representation (Moscovici, 1961) focuses on group processes that in turn form the beliefs and attitudes of the individual. Traditional theories about attitude stem from the notion that attitudes either change because of events in the environment of the individual, or persuasion from an external source. Social representation theory, however, states that a change or creation of a new object such as effectuation is something commonly created within the group.

According to traditional social psychology, we change our attitudes both in an active way, as portrayed in the theory of reasoned action, and in more passive ways, such as mere exposure, as described by Zajonc (1968), and in operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). They lead to the same result, but the difference is that passive means of attitude change in general lead to a lower degree of reticence over time. However, these theories do not consider the co-creation of social objects and the consequences of breaking the norms. These are factors that are best explained by the theory of social representations. As we mentioned before, the individual can have a belief that is contradictory to the beliefs of the group, and when a belief or attitude has become institutionalised and reified, it is difficult for the individual to contradict the group without consequences, which can be social or more material in nature, such as the loss of credit possibilities.

This means that an aspiring entrepreneur already from the beginning is forced to adopt causal reasoning since he/she is forced to go through the process of creating a business plan. This, together with the institutionalised learning process, where the student is moulded into adopting a causal form of reasoning, can in some groups lead to a more difficult transition from the widely accepted form to a different one.

Effectual logic is by no means a new logic, and it was not invented by Sarasvathy (2001), but merely described. We tend to argue that effectual logic has existed since the advent of man. However, causal logic has been institutionalised, at least in the realm of business, to the extent that stakeholders, both internal and external, often demand manifestations of causal reasoning such as SWOT analysis and business plans from aspiring entrepreneurs. Perhaps it is also the case that the more an entrepreneur has proven him or herself in terms of success, the more freedom the person enjoys. However, for the new entrepreneur, there are many hurdles to adopting an effectual logic. The way the shift occurs is in other means a product of the shift in beliefs and attitudes at an individual level, but it also depends on the group to which the individual belongs.

The question is also why most student entrepreneurs favoured effectuation as a decision-making logic, even if traditional education teaches causation. Perhaps it has to do with the fact that student entrepreneurs and non-serial entrepreneurs often operate with constraints in the form of budget, network and knowledge to a higher degree than entrepreneurs in general, although Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) also supports this conclusion. Even so, the remaining entrepreneurs who favour causation often have a cognitive journey ahead of them in the form of a change of beliefs and attitudes, constrained by group or stakeholder expectations. As the entrepreneur gains positive experience and exposure to effectuation, the concept becomes more appealing, and as the concept is anchored and objectified, acceptance towards it grows.

Our interviews show that 8 out of 10 entrepreneurs with university education stated that their education taught them to adopt a causal decision-making logic, two were unsure, and none stated that effectuation was taught in their respective university education programmes, or that they favoured effectuation after graduation. This leads us to the conclusion that effectuation is something that entrepreneurs learn to adopt after their university education.

In addition, the interviews reveal that 7 out of 10 entrepreneurs also stated that they favoured the decision-making logic that they were exposed to immediately after their education, meaning that the education system tends to change attitudes towards causation through mere exposure. It is worth noting that 8 out of 10 entrepreneurs stated that their attitude changed after they became entrepreneurs, and 8 out of 10 said that after becoming entrepreneurs, they favoured effectual logic. According to some previous studies, large, non-entrepreneurial firms are more causal than smaller ones (Sarasvahy, 2001), whilst others such as Reymen et al. (2015), and perhaps most notably Arend et al. (2015), hold a divergent view. Thus, according to the views of Sarasvathy (2001), if the studied firms were large, this could explain why the entrepreneurs might prefer causation, and vice versa, i.e. if the studied firms were small, then this could explain why entrepreneurs might prefer effectuation.

When one looks at the group that has more than five years’ experience of entrepreneurship (5 persons out of 10), the result is overwhelmingly in favour of effectuation, since 5 out of 5 entrepreneurs (with entrepreneurial experience longer than five years) said they prefer effectuation, which is in contrast to the group with less than five years’ experience, where 3 out of 5 preferred effectuation.

Regarding the question of whether the subjects put an amount of cognitive effort into the process of changing their decision-making logic, most subjects replied that they did, but not extensively, and 70 % of those who changed their decision-making logic said they did so because they experienced mental discomfort stemming from adopting the previously used logic (Festinger, 1957; Martinie et al., 2017). The same also applies when it comes to the issue of whether they reflected a lot on the positive or negative consequences of adopting one or the other logics, implying that there is a strong correlation with the fundamental principles of the theory of reasoned action. When it comes to the question of input from others as a factor that determines the decision-making logic preferred or applied, only two subjects replied that it played a notable role. The same subjects answered that decision-making logic and decision-making in general were something they discussed with others, while 6 out of 10 subjects replied that this was not an issue that they discussed extensively with others, and 2 out of 10 replied that input from others played some role. Five out of 10 entrepreneurs also answered “no” to the question regarding whether the change of decision-making logic was the result of a group process of some sort, and only two answered that this was so, one - to some extent, and two stated the question was - non-applicable as they had not changed their decision-making logic. 4 out of 10 also felt a reluctance when it came to changing decision-making logic, suggesting that there is often resistance to change. Furthermore, there was no difference between those with under five years of entrepreneurial experience and those with experience exceeding five years. In the open-ended question, where the respondents were asked to describe the process leading to attitude change and the change of decision-making logic, they described in varying words a process where they increasingly felt that the logic they previously used did not produce the expected returns, or, in other words, the positive outcomes were not as expected. One entrepreneur stated:

“What I learned at university later, when I opened my first business, turned out not to be true in reality (laughing)... in a small business, one cannot make extensive plans, implement, and follow up; there is no free money or endless resources. Therefore, I concluded that I needed to act based on what I had, instead of following what I learned in school. I decided to do what I could, with what I had. It was a painful awakening, and it took time to break free. If I had not, the consequence would have been bankruptcy at some point, of that I am sure (laughing). Outcomes and consequences were topics that circled my mind for a long period. It took me a long period before I even heard of other ways of doing things than the ways we learned in school. I think that the university is an authority, and also when you work together with your fellow students, you tend not to question: group work, for example, instead tends to reinforce what the school is teaching, since no one questions authority in any meaningful way, and group work means that your own beliefs are reinforced by others. As an entrepreneur, you do not often discuss the same topics as you do at university with others since the process of learning is constructed and controlled by others, which means that later in life you do not get the same opportunity to exchange ideas”.

The entrepreneur described a process where he at first did not know about any other logics, and that the logic taught at university was later reinforced in interaction with fellow students. Here, we see clear elements from social representation (Moscovici, 1961): anchoring and objectification, something that, according to the entrepreneur, was harder to achieve later in life, and that points to the fact that social representation is more applicable in a group setting than in an entrepreneurial setting, where those issues are perhaps not raised.

One of the two entrepreneurs who changed his logic stated:

“As for the definition you provided to me, causation is most definitely the logic I learned in school. I think it stuck with me for some time; I think, in fact, it made it difficult for me since I was too rigid for my own good. Later, when I saw the need to change, I did not know it then, but what I did was that I changed to what I later got to know as effectuation. The process was not easy, and it caused me a lot of stress”.

The other entrepreneur, who was one of the 20% who always preferred causation, stated:

“For me, there was no need to change my decision-making logic. I can understand that in some businesses, there is a great deal of uncertainty, but for me, that was never the case. I think, however, you can find elements of effectuation in my reasoning because as an entrepreneur, you always need to handle uncertainty. However, I need a framework: to skip formulating goals and implementing programmes would not work for me. Perhaps decision-making logics are determined both by situational factors, but also by the personality of the entrepreneur”.

An interesting fact to note is also that the entrepreneurs who continued to apply causation both stated that causation and causal logic was something they learned at university, mainly through low-effort processes such as heuristics, and also in dynamic interactions according to social representations. This shows that the cultural and institutional aspects described by Laskovaia & Shirokova (2017); North (1991) are at play. The second entrepreneur, who continued to apply causation, stated:

“For me, I never thought about any logics or rather changing mine. I simply did what I learned in school; in hindsight, maybe I should have been more open because I think the reluctance or fear of change led to many hardships. I think our educational system should be more open and embrace more and different ideas. I felt like causation was the only way to go about it, and I would say I had my education to thank for that (laughing). When I look at things now, I think I felt mental discomfort or stress because I felt that my way of going about things was wrong, but I did not dare to challenge what I was taught. I sometimes wish I would have because it would have spared me a lot of pain. I thought about the consequences, most of all related to mine, because I quickly realised that things were not as easy as Kotler said they were (laughing). Sadly, I did not know of any other way back when I started my career; now, I think it is too late. I got used to my way of doing things. With that said, I think there are also times where I used effectual thinking, especially when I could not muster the resources to go ahead with a more traditional way of doing things”.

This underlines the principle of cognitive dissonance that people often have resistance to new ideas (Martinie et al., 2017). The entrepreneur suffered hardships and increasingly understood that his way of doing things was not optimal. There was a discrepancy or conflict between his values that favoured causation; but still, he felt resistance when it came to changing his attitudes.

In general, our results point to the fact that social representation theory cannot explain why people turn from adopting one decision-making model to another. However, the person interviewed kept on with causal reasoning, since he did not know about effectuation or other ways of doing things. If effectual reasoning had been the subject of anchoring and objectification, perhaps the leap would not have been so great. The question is also whether people are aware of the processes described in the theory of social representation, as we are seldom aware of these kinds of processes that do not draw our immediate attention, which in our view means that social representations theory cannot be ruled out.

Our study further shows that entrepreneurs are, to a large extent, aware of factors within themselves and their environments, such as the positive and negative consequences of adopting one or the other decision-making model.

The results from the interviews also underline that decision-making is something that the entrepreneurs did not think about in the stages before and during education, as within those stages, they put little thought into these issues. After becoming entrepreneurs, the score was higher: on a 0 to 7 scale, where 0 is none, 4 is a fair amount, and 7 is extensive, the average score was 5 after they became entrepreneurs. This can be compared to 0 before entering university, and 1 during their studies. This makes a case for high-effort processes after becoming an entrepreneur and low-effort before the entrepreneurial debut as an explanation for the formation and change of attitudes regarding decision-making logic.

Our study also showed that 60% of entrepreneurs applied both causal and effectual logic and that there was a high correlation between preferred logic and applied logic - 90%. 50% of the entrepreneurs also stated that their decision-making logic had been fairly stable over time, perhaps a sign that they use a combination of logic, applied in different periods of the firm's life, something that also became clear during our interviews.

Regarding the age of the entrepreneurs, the sample was too small to draw a definite conclusion. However, from what we could read out of the correlation between age and experience, there is a broader tendency for older entrepreneurs to prefer effectual logic, because of a larger exposure to entrepreneurship, something that is also reflected in the answers given by the interviewee: this has also been confirmed in a study by Harms & Schiele (2012).

Those entrepreneurs with a broader experience of entrepreneurship have, to a larger extent, reflected upon the consequences of their decision-making logic than those with less experience. Also, those of younger age are probably more prone to experience a lingering effect of their inculcation into one logic, which is still active, than those who have spent a long time outside of the university and are operating outside in an entrepreneurial context. The effects of this inculcation, stemming from university, have, in other words, grown weaker, and the effects of high effort processes have increased in strength due to the cognitive processes within the entrepreneur him or herself. Also, with gender, the sample was too small to draw any conclusion, and gender difference was not a primary goal of investigation. However, it is well established in research that women tend to take fewer risks than men (Waldron, McCloskey & Earle, 2005), and have slightly different personality traits described in the big five personality trait model, such as agreeableness, extraversion and neuroticism. In this study, gender differences were not substantial (Weisberg et al., 2011).

One difference that can be noted is in the answers, where men tend to be more direct, whilst women appear to have a more uncertain tone, as exemplified in the answer of the female respondent, aged 28 from Ukraine (Q1), who stated “Well, given your definitions and given the size of my business, I would say I am leaning towards effectuation now. However, back then, I was taught causation”.

Gender differences can be identified, but not to the level where one can say they are significant enough to make conclusions on the process of the change of attitudes in an entrepreneurial context. What can be said, however, is that women, because of their slight variance in personality traits such as openness and extraversion, should theoretically be more open to changing their attitude as well as being more influenced by other individuals and group dynamics than men, who score lower than women on the same traits. Another aspect is the cultural context from which the entrepreneur originates and the personality traits of the entrepreneur - a case made by Laskovaia & Shirokova (2017); Dilli & Westerhuis (2018). The school system and what is taught to the students is a result of the culture and the institutions of society, something that, in turn, partly shapes personality traits (Hofstede & McCrae, 2016). There is a relationship between culture, institutions, the educational system, identity, personality and the decision-making logic applied and preferred (Alsos et al., 2016). According to the research by Laskovaia & Shirokova (2017) and Hofstede and McCrae (2017), the results may have differed if we had conducted a country-specific study or engaged in a study with a much broader sample, also involving countries more different in culture than the ones found in the sample of this study. There is a debate regarding whether the adoption of effectuation vs causation is stable, depends on circumstances or where in the lifecycle the firm is. Our study showed that there is a tendency that the preferred and applied logic moves from causal to effectual as the entrepreneur gains experience, but we cannot rule out the possibility that effectuation is applied to a different extent during certain events in the firm's life, or if applied according to a situation. However, according to Velu and Jakob (2016), managers with entrepreneurial traits strengthen the innovation ability of the firm. Therefore, people with entrepreneurial traits who use effectuation might be overrepresented since entrepreneurial skills have a positive effect on the firm's survival during the first part of its life.

Conclusions, Managerial Implications, Limitations, Future Research and Propositions Development

Conclusions

Our study shows that entrepreneurs, to a high degree (8 out of 10 entrepreneurs), perceive that causation is the predominant decision-making logic taught in business programmes at universities. The vast majority of those entrepreneurs after graduation favour causation, but during their experience as entrepreneurs they shift towards effectuation, and that, according to our study, is a gradual process, where there is a significant difference between those with shorter and those with longer experience in entrepreneurship. Our study further shows that the process is mostly associated with what is characteristic of high-effort processes, and more specifically described in the theory of reasoned action, and to a certain extent with cognitive dissonance, since there is mental stress or discomfort involved that is related to cognitive dissonance. For the most part, the subjects change their values since their actions cannot be altered in retrospect. Our study was partially inconclusive when it comes to differentiating between cognitive responses and reasoned action, although the results point more in the direction of reasoned action as an explanation.

According to our study, low-effort processes, play a minimal role, the same as collective processes such as those described in the theory of social representation after graduation, and they cannot be a driver of change. However, the theory cannot be fully disregarded: if we do not know any other way of doing things, we tend to continue along the path we started on. As the interviews have revealed, social representation theory can partly explain the processes at university, where things are anchored and objectified in dynamic social processes involving others, such as group work.

Low-effort processes also seem to be less important as an explanation of attitude change among entrepreneurs because of the importance of business in the life of the entrepreneurs. Therefore, one can conclude that low-effort processes play only a marginal role in the attitude change that occurred after the point of graduation, but a larger role in the time leading up to graduation.

Our study also shows that the preference for effectuation grows higher in association with a higher level of experience.

Implications and limitations

Regarding the implications of this study, they can be divided into theoretical and managerial ones. The study theoretically implies that causation versus effectuation use is not black or white, but rather a mixture of grey tones, e.g. someone can be 70% causal and 30% effectual in making a specific decision, and 40% causal but 60% effectual in making another decision. Moreover, most people do not analyse their decisions in this way, and they also do not always clearly remember the reasons for their choice. For example, they may try to give a better impression of themselves, and therefore state that their decision was based on some systematic reasoning, whereas it could have simply been of the “what feels best” type.

Regarding managerial implications, one can think that entrepreneurs with an adequate level of education implement effectuation logic rather than causation logic. However, it is not very clear which of the logics is more effective, depending on numerous factors such as financial and environmental ones.

This study has some limitations. For example, it is a qualitative study of ten entrepreneurs, and therefore the generalisability of the findings can be questioned. Additionally, the age and profession of the participants and the industry they are operating in are varied. Individual differences, such as personality traits, have also not been examined and considered. Furthermore, there is an additional limitation due to a possible lack of understanding about the different perspectives from the side of the interviewees. Additionally, one more limitation of this study is that it builds upon retrospective data.

The qualitative method also makes it more difficult to draw definite conclusions, due to the limitations in both scope and the fact that the answers are interpreted by the interviewer, and his/her own bias might play a larger role than in a quantitative study.

Future Research and Propositions Development

Future research should be performed on a larger scale with a larger sample of entrepreneurs, as our study only shows tendencies. An attitudinal study can also be undertaken based on the attitudes of the ten interviewees of this study. A similar study was carried out in the different context of exporting attitudes (Coudounaris, 2012). A suggestion might be to replicate this study using a quantitative approach and in a specific industry, e.g. the IT sector.

According to Sarasvathy (2001, 2008), causation has long been the predominant logic taught in our classrooms today at business schools at the university level. Despite this, Sarasvathy (2001) claims that most entrepreneurs favour effectuation as a decision-making model.

Furthermore, there must have been a transformation in preferences shifting from causation to effectuation. Even though Sarasvathy (2001); Sarasvathy et al. (2008) assume that attitudes are something static, most social psychologists disagree with that notion (e.g. Arend et al., 2015) and view our attitudes as ones that are continually evolving.

Proposition 1: Education in business is an education that indoctrinates future entrepreneurs in the decision-making logic of causation.

According to the works of Sarasvathy (2001, 2008), most experienced entrepreneurs prefer effectuation as a decision-making logic. This has to do with the fact that as entrepreneurs gain more and more experience, the shift then is one towards effectuation. Sarasvathy acknowledges that there is a change in decision-making logic, but she does not attribute it to any change in logic, but rather through the lens of resources and networks. However, if one has a change of perception towards an object, one also needs to have a change of attitude. Allport (1935, 1954); Eagly & Chaiken (1993) refute this static view on attitudes.

Proposition 2: Most entrepreneurs prefer effectuation as a decision-making logic, and attitudes are subject to change and are not static constructs in the way that Sarasvathy and Dew (2008) assume.

The reason for this is that the more important something is for us, the more thought processing capacity we use when thinking and reflecting on it. We assume that for an entrepreneur, his or her business should be of such importance that a high degree of cognitive effort is put into it. The theory stipulates that the more favourable a presumed outcome is associated with behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1969; Fishbein, 1967) such as effectuation, the more favourable an attitude the person will have towards effectuation as a decision-making model. The difference here is that there is an active process involved and not just a generally positive such as mere exposure. It seems we learn to associate different types of behaviours with different types of rewards, dissonance processes or where group processes form our attitudes towards an object such as in social representations theory. Social representation, to a certain extent, includes an external locus of control, something that is atypical of the average entrepreneur. However, in our propositions, we do not entirely refute other forms of attitude-changing processes.

Proposition 3: The shift in logic is mainly driven through high-effort processes.

We propose that the shift towards effectuation as a preferred decision-making logic will grow exponentially over time and that an entrepreneur with a long experience of business will have a greater tendency to prefer effectuation. First of all, an entrepreneur who has done business for a longer time will have gained greater experience, learned through trial and error, and have been subject to low effort, high effort, and social representation processes (anchoring and objectification). None of those processes can be excluded as means of attitude change, but we propose that high-effort processes play a more prominent role than the other means of attitude change. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) stated that serial entrepreneurs were prone to adopt effectual reasoning, meaning that over time the tendency towards effectuation should be more significant.

Proposition 4: Entrepreneurs with more than five years of experience show a higher degree of favourability towards effectuation compared to those with 2-5 years of experience.

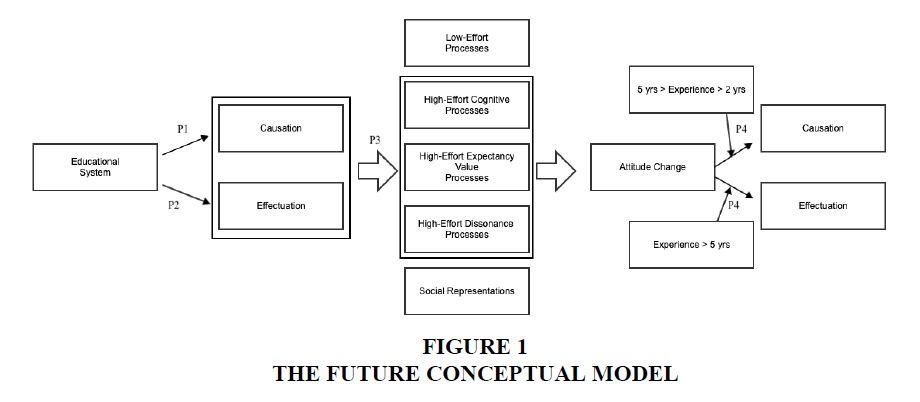

Figure 1 above shows the conceptual model, which is suitable for the tertiary education system. The question is whether the educational system indoctrinates students of effectual logic. We propose that this is the case. Then the question arises as to whether the following five antecedents, i.e. a) low effort processes, b) high effort processes - cognitive responses, c) high effort processes - expectancy-value processes, d) high effort processes - dissonance processes, or e) social representation, constitute the main drivers of attitude change. The other important question is whether attitudes towards the two types of decision-making model logics are stable over time, and whether they are subject to change. Finally, a case study of an IT recruitment company has recently been investigated in Tallinn, revealing very interesting insights about the effectuation versus causation of the managing staff of the company (Arvidsson & Coudounaris, 2020).

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1969) The prediction of behavioral intentions in a choice situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(4), 400-416.

- Albarracin, D., & Shavitt, S. (2018) Attitudes and Attitude Change. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 299-327. Alison, C., Dashtipour, P., Keshet, S., & Righi, C. (2009) We don’t share! The social representation approach, enactivism and the fundamental incompatibilities between the two. Culture and Psychology, 15(1), 83-95.

- Allport, G.W. (1935) Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology. Worcester, Mass: Clark University Press.

- Allport, G.W. (1954) The historical background of modern social psychology. In G. Lindzey (Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 3-56). Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Alsos, G.A., Clausen, T.H., Hytti, U., & Solvoll, S. (2016) Entrepreneurs, social identity and the preference of causal and effectual behaviours in start-up processes. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 28(4), 234-258.

- Arend, R.J., Sarooghi, H., & Burkemper, A. (2015) Effectuation as ineffectual? Applying the 3E theory-assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 630-651.

- Arvidsson, H.G.S., & Coudounaris, D.N. (2020) Effectuation versus causation: A case study of an IT recruitment firm. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, forthcoming.

- Ayalew, M.M., & Zeleke, S.A. (2018) Modeling the impact of entrepreneurial attitude on self-employment intention among engineering students in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 1-27.

- Baier-Fuentes, H., Merigó, J.M., Amorós, J.E., & Gaviria-Marín, M. (2018) International entrepreneurship: A bibliometric overview. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 385-429.

- Bauer, M.W., & Gaskell, G. (1999) Towards a paradigm for research on social representations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 29(2), 163-186.

- Breckler, S.J., & Wiggins, E.C. (1992) On defining attitude and attitude theory: Once more with feeling. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.) Attitude Structure and Function (pp. 407–427). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Chaib, M., Danermark, B., & Selander, S. (2010) Education, Professionalization and Social Representations: On the Transformation of Social Knowledge. Routledge, New York.

- Chetty, S., Partanen, J., Rasmussen, J., & Servais, P. (2015) Contextualising case studies in entrepreneurship: A tandem approach to conducting a longitudinal cross-country case study. International Small Business Journal, 32(7), 818-829.

- Ciszewska–Mlinaric, M., Obloj, K., & Wasowska, A. (2016) Effectuation and causation: Two decision making logics of INVs at the early stage of growth and internationalization. Journal for East European Management Studies, 21(3), 275-297.

- Coudounaris, D.N. (2012) An attitudinal factorial model explaining the export attitudes of managerial staff. Journal of Current Research in Global Business, 15(23), 76-100.

- Coudounaris, D.N., & Arvidsson, H.G.S. (2019) Recent literature review on effectuation. Academy of Marketing Conference 2019, International Marketing Track, 2-4 July, London, UK, pp. 1-18.

- Coviello, N.E., McDougall, P.P., & Oviatt, B.M. (2011) The emergence, advance and future of international entrepreneurship research - An introduction to the special forum. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 625- 631.

- Cyert, R.M., & March, J.G. (1963) A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

- Dilli, S., & Westerhuis, G. (2018) How institutions and gender differences in education shape entrepreneurial activity: A cross-national perspective. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 371-392.

- Dutta, D.K., Gwebu, K.L., & Wang, J. (2015) Personal innovativeness in technology, related knowledge, experience and entrepreneurial intentions in emerging technology industries: A process of causation and effectuation? International Entrepreneur and Management Journal, 11, 529 – 555.

- Eagly, A.H., & Chaiken, S. (1993) The Psychology of Attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Fort Worth, TX

- Ehret, P.J., Monroe, B.M., & Read, S.J. (2015) Modeling the dynamics of evaluation: A multilevel neural network implementation of the iterative reprocessing model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev., 19(2), 148–76.

- Festinger, L. (1957) A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford Uni. Press. Stanford, CA

- Fishbein, M. (1967) A behavior theory approach to the relations between beliefs about an object and the attitude toward the object. In M. Fishbein (Ed.), Readings in Attitude Theory and Measurement (pp. 389-400). John Wiley & Sons. New York.

- Harms, R., & Schiele, H. (2012) Antecedents and consequences of effectuation and causation in the international new venture process. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 10(2), 95-116.

- Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R.R. (2004) Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture, Cross-Cultural Research, 38(1), 52-88.

- Jovchelovitch, S. (2007) Knowledge in Context: Representations, Community and Culture. London: Routledge. Knight, F.H. (1921) Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

- Knight, G.A., & Liesch, P.W. (2016) Internationalization: From incremental to born Global. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 93-102.

- Kotler, P. (1991) Marketing Management. 7th Edition, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs. Krech, D., & Crutchfield, R.S. (1948) Theory and Problems of Social Psychology. New York: MacGraw-Hill.

- Laskovaia, A., & Shirokova, G. (2017) National culture, effectuation and new venture performance: Global evidence from student entrepreneurs. Small Business Economist, 49, 687-709.

- Laszlo, J. (1997) Narrative organisation of social representations. Papers on Social Representations, 6(2), 93-190.

- Maine, E., Soh, P., & Dos Santos, N. (2015) The role of entrepreneurial decision-making in opportunity creation and recognition. Technovation, 39/40(1), 53-72.

- March, J. (1982) Theories of choice and making decisions. Society, 20(1), 29-38.

- March, J.G. (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71-87. March, J., & Simon, H. (1958) Organizations. Wiley, Oxford.

- Martinie, M., Almecija, Y., Ros, C., & Gil, S. (2017) Incidental mood state before dissonance induction affects attitude change. PloS One, 12(7), e0180531.

- Matalamäki, M.J. (2017) Effectuation, an emerging theory of entrepreneurship – Towards a mature stage of the development. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24, 928-949.

- McDougall, P.P. (1989) International versus domestic entrepreneurship: New venture strategic behavior and industry structure. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(6), 387-400.

- McDougall, P.P., & Oviatt, B.M. (2000) International entrepreneurship: The intersection of two research paths. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 902-906.

- Mintzberg, H. (1978) Patterns in strategy formation. Management Science, 24(9), 934-948.

- Mintzberg, H. (1985) Strategy formation in an adhocracy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(2), 160-197.

- Moreland, R.L., & Beach, S.R. (1992) Exposure effects in the classroom: The development of affinity among students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28(3), 255-276.

- Moscovici, S. (1961) La Psychanalyse, Son Image et Son Public. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

- Moscovici, S. (1973) Foreword. In C. Herzlich (Ed.), Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Analysis, (pp. ix– xiv), London/New York: Academic Press.

- Mthanti, T.S., & Urban, B. (2014) Effectuation and entrepreneurial orientation on high-technology firms. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 26(2), 121-133.

- North, D.C. (1991) Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97-112.

- Nummela, N., Saarenketo, S., Jokela, P., & Loane, S. (2014) Strategic decision-making of a born global: A comparative study from three small economies. Management International Review, 54, 527-550.

- Oviatt, B.M., & McDougall, P.P. (2005) The internationalization of entrepreneurship. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(1), 2-8.