Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 5

The Role of Sociocultural Factors in TNI AD Non-commissioned Officers Motivations, Goals, and Pro-organizational Behavior

Fikri Ferdian, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada

Agus Heruanto Hadna, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada

Agus Joko Pitoyo, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada

Dewi Haryani Susilastuti, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada

Citation Information: Ferdian, F., Hadna, A.H.Pitoyo, A.J., & Susilastuti, D.H. (2023). The role of sociocultural factors in tni ad non-commissioned officer’s motivations, goals, and pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 26(5), 1-15.

Abstract

The present research aims to investigate the role of sociocultural factors in describing and predicting the Indonesian Army NCOs’ (Bintara TNI-AD) motivations and goals in their relation to pro-organizational behavior. The data were collected through a survey using a Likert-scale questionnaire. A total of 676 Bintara TNI AD from Papua, Maluku, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan participated in the research. The collected data were subsequently analyzed using a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach using the IBM SPSS AMOS software. This study revealed that the sociocultural factors in question influence the motivations and goals of Bintara TNI AD, which in turn shape their organizational behavior. Following the findings, implications and suggestions for future research are also discussed.

Keywords

Survey, SEM, Likert-Scale, Sociocultural Factor, Motivation

Introduction

The Indonesian Army (TNI AD) is an integral part of the national defense system of Indonesia. Since its founding, TNI AD has functioned as a state apparatus and been assigned with the duty of safeguarding and protecting the country’s security in addition to conducting land-based military operations. The fundamental purpose of TNI AD’s duty is twofold. The first is to reinforce and maintain the sovereignty and integrity of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) as established by the five principles of Indonesia's philosophical foundation (Pancasila) and the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia (UUD 1945). The second is to protect the entire Indonesian nation and its homeland from all kinds of threats and disturbances that can harm the nation’s unity and peace.

Hermawan (2016) discloses in a TNI AD’s website post that being a TNI means signing up for a not high paying job. His statement is in line with what Pangdam II/Swj Mayjen TNI Purwadi Mukson, S.I.P., expresses in a written mandate that was read out by Wadanrindam II/Swj Letnan Kolonel Inf M. Soleh, while acting as the inspector of the opening ceremony of the junior enlisted professional military education (Diktama) TNI AD – Period I Phase I of the 2016-17 academic year at Lapangan Upacara Secata (the Ceremony Field of Secata), Rindam II/Swj, Lahat. According to Hermawan (2016), the mandate implies that a professional military career is not an occupation that offers high earnings potential. In reality, it is a career replete with challenges, risks, and sacrifices. A soldier is expected to devote his body and soul to the safety of the nation and the NKRI’s sovereignty

Surprisingly, while there is a growing negative perception of TNI AD personnel nowadays, the number of civilians wishing to join TNI AD as an NCO (Bintara) is increasing. This tendency is particularly apparent in the eastern part of Indonesia. It has been reported in a news post by Talla (2021), for example, that the number of people enlisting as a Bintara of the TNI AD service for 2021 intake in Kodim 1504/Ambon in the city of Ambon was higher than that in the previous year. Another news post from Fua (2021) informs about a significant increase in the number of civilians applying for the same position in the Province of Sulawesi Tenggara as compared to the number in the previous year.

Likewise, a news post from Antara (2021) records that many young native Papuans show their enthusiasm of joining the forces. This trend has motivated members of Non- Commission Officer Military Rayon Command (Babinsa Koramil) to go from village to village to encourage them to apply (Antara, 2021). In still another report about this phenomenon, written by Epu (2021), the number of citizens in Flores who applied for Bintara TNI-AD duty shows a dramatic increase compared to the previous year. These pieces of evidence clearly prove that this career path is still an attractive choice for many young Indonesians.

In connection with this phenomenon, an interesting development has arisen. Hanafi & Mariono (2019) report that since 2019, Bintara TNI AD recruitment has implemented an affirmation policy that provides preferences to applicants from the local community when recruiting for Babinsa duty. Moreover, an internal source of TNI AD informed that this policy is widely implemented in Area Military Command (Kodam) XVII/Cen in Papua, Kodam XVIII/Ksr in West Papua, Kodam XVI/Ptm in Ambon, and Kodam XIV/Hsn in Sulawesi.

This policy is intended to increase the number of civilians interested in joining the TNI, specifically as a Bintara. This is thus an interesting phenomenon; to the fact mentioned earlier that although there are many negative perceptions of Bintara TNI AD, there are still a lot of people who want to be a Bintara.

In light of the fact that a large number of young women and men from various regions, especially the eastern parts of Indonesia, are keen on enlisting as a Bintara, this article presents research on their motivations and goals for becoming a Bintara TNI AD based on which their behavior at work or pro-organizational behavior can be explained and predicted.

For the purpose of understanding, explaining, and predicting the phenomenon, the Achievement Goal Theory, explicated by Elliot & Harackiewicz (1996); Anderman et al (2003); Pintrich et al (2003); Shih (2005), is considered a suitable approach. This theory focuses on one’s goal(s) of a particular achievement task, not one’s overall life purpose (Pintrich et al., 2003). The present research attempts to discover what motivates an individual to accomplish a particular task. In other words, why he/she wants to achieve a particular goal (Anderman et al., 2003; Eliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Midgley et al., 2001; Pintrich, 2000).

The achievement goal theory holds that an individual may have the same motivation to do a particular task, but he/she does not necessarily have the same reason to do so (Anderman et al., 2003). In relation to the topic under discussion, this research aims to look at the reason for the foregoing task accomplishment as a way to understand what motivates Indonesian civilians to enlist as a Bintara.

As explained by Covington (2000), Ames (1992), and Friedel et al. (2007), along with the achievement goal theory, another aspect that is considered influential in an individual’s goal orientation or achievement orientation is sociocultural factors. The achievement goal theory posits that social environment, such as one’s local community or family, has a significant effect on one’s behavior (Ames, 1990).

Ames (1992) observes that the prevailing expectations and behaviors of other people in an individual’s environment may affect the development of his/her actual behavior both positively and negatively. In addition to his achievement behavior, an individual’s perception of significant others such as parents, friends, colleagues and the like, can have certain effects on his/her belief and motivation (Ames, 1992). Sociocultural factors also contribute to an individual’s goals and motivations in engaging in certain behavior (Covington, 2000; Friedel et al., 2007).

This observation concurs with the findings of studies conducted by Griffith & Perry (1993), Griffith (2008), and Gorman & Thomas (1991) on motivation and goal to become a soldier. These studies found that the sociocultural factors that play a role in shaping an individual’s motivation to join the military include an intention to reduce the family’s burden, self-actualization, economic necessities, patriotism, and being born into a military family. In addition, Raabe et al. (2020) use a Self Determination Theory in their study of American soldiers to explore the social factors that are connected to an individual’s three basic necessities, namely competence, autonomy, and connectedness, as well as the soldiers’ attitude and behavior. According to their findings, social factors play a crucial role in shaping their research participants’ motivations and goals for engaging in a particular behavior.

Furthermore, the achievement goal theory, according to Latham & Locke (1991), Elliot & Harackiewicz (1996), Anderman et al. (2003), Pintrich et al. (2003), and Shih (2005), assumes that a goal has a pervasive effect on employees’ behavior and performance in an organization and on management practice. Nearly all modern organizations adopt a number of goal setting methods for their operations. The TNI AD as a modern organization is not without differences. Every Bintara sets their own goal to achieve in their career as a TNI soldier.

However, as pointed out by Latham & Locke (1991), Elliot & Harackiewicz (1996), Anderman et al. (2003), Pintrich et al. (2003), and Shih (2005), while the achievement goal theory offers some advantages, there is a number of limitations that are related to the process of achievement goal setting. First, the theory only deals with organizational members for aspects of performance achievement with quantifiable indicators at the expense of aspects of work performance without reliable quantifiable indicators. According to Latham & Locke (1991), Elliot & Harackiewicz (1996), Anderman et al. (2003), Pintrich et al. (2003), and Shih (2005), it is commonly identified with the saying “what gets measured gets done.”

Second, the achievement goal theory is relevant only to an established job. It will no longer be effective for the case when the members of the organization start to learn a new job that is more complex in nature. Therefore, the focus of this article is mainly on proorganizational behavior as defined by Organ (1988). Organ describes it as an individual’s voluntary commitment to an organization or a company that is not included in their employment contract. This definition implies three important elements:

1. Compliance. This element refers to the organization members’ respectful attitude towards the already well-organized structures and processes. Members of the organization are responsible for adhering to the extant laws and at the same time are protected by them. Some examples are the law that requires citizens to pay taxes, drive on the right side of the road, refrain from violating the rights of others, and be willing to risk their lives, particularly for those who work in military service.

2. Loyalty. This element refers to organization members’ responsibility to incorporate the interests of others, as well as the organization as a whole and the values it stands for in the individual welfare function. Among the citizenship behaviors that are included in this category are the unremunerated contributions that include business, money, or property; efforts to protect and/or improve the organization’s external reputation; and willingness to work together with others for common interests instead of looking for life chances for free.

3. Participation. This element refers to organization members’ responsibility to participate in the government. It corresponds to Aristotle’s statement that “men are praised for knowing both how to rule and how to obey, and he is said to be a citizen of approved virtue who is able to do both” (1941, p. 1181) (see Graham, 1991). Hence, members of an organization should assist in the enforcement of laws and bring lawbreakers to justice. In addition, they are obligated to participate, both directly and indirectly, in the amendment of the existing regulation in response to the newly emerging facts and the latest advancement of knowledge of common interests. Therefore, this kind of organizational citizenship behavior involves one’s willingness to dedicate more time and energy than one should, ensure good information exchange, share various information and ideas with others, participate in discussions about controversial issues, voice thoughts in accordance with the existing rules, and encourage other people to do the same.

Accordingly, we treat the pro-organizational behavior as a variable with dimensions that are challenging to measure (Smith et al., 1983; Graham, 1991; Organ, 1997) and as a target variable for the present research model. Smith et al. (1983), Graham (1991), and Organ (1997) further explain that factors or dimensions that constitute pro-organizational behavior do not lend themselves to measurement because different individuals have different perceptions of the matter. This research is intended to reveal how Bintara TNI AD individuals’ roles and goals in performing their duties affect their pro-organizational behavior.

Literature Review

Sociocultural Factors

Gorman & Thomas (1991), Griffith & Perry (1993), and Griffith (2008) agree that certain sociocultural factors may shape an individual’s motivations and goals when he/she decides to join the armed forces. These factors include: (1) the intention to reduce the family’s burden, (2) self-actualization, (3) economic necessities, (4) patriotism, and (5) being born into a military family.

Apparently, this is also true for those in the eastern parts of Indonesia who want to be a Bintara TNI-AD. A preliminary interview with these young people revealed that sociocultural factors that motivate them to enlist themselves in the Army and shape their goals for doing so are: the laws/regulations, family, the reference group, social class, and culture.

Motivation

There have been a number of studies showing that motivation tends to promote behaviors that are valued by social groups that include retention, positive WOM, and involvement (Arnett et al., 2003; Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Prestige perception of the organization, distinctiveness, and social satisfaction can give positive influence on proorganizational behavior (Arnett et al., 2003; Weisman et al., 2023). Recent studies on the subject matter have provided adequate evidence that prestige perception of the organization, distinctiveness, and social satisfaction as a motivational factor can increase proorganizational behavior.

Goal

Goal denotes a cognitive representation of a favorable outcome that serves as a reference point and affects the evaluation of information and options, attitude, and behavior (Woodruff, 2017). Therefore, objectives associated with registration and follow-up services will impact how prospective members perceive and evaluate the organization and membership. Substantial interrelationships between goals, attitude, and behavior render goal a useful indicator to pinpoint the consequences of an individual’s attitude and behavior when deciding to join a particular organization. In this study, a goal is construed as a personal target that is considered achievable by registering and being a member of the Army.

Pro-organizational behavior

The concept pro-organizational behavior describes the possibility of organizational citizenship behavior to function as a normative behavior that ensures a cohesive relationship among employees. In turn, such cohesive relationship can serve as a strong predictor of the improvement in members’ work performance (Podsakoff et al., 2014). Many previous studies have shown that pro-organizational behavior tends to correlate positively with members’ performance (de Geus et al., 2020). Pro-organizational behavior in the members of an organization contributes to the organization’s efficacy and performance by fostering the formation of social capital and facilitating social movements. In other words, an individual who demonstrates pro-organizational behavior in his/her workplace may contribute to the reinforcement of the social structure that has been built by the organization (Bolino et al., 2013; Srivastava & Madan, 2022).

Hypotheses

The influence of sociocultural factors on motivation

Furthermore, some previous studies show that motivation is flexible and responsive to changes in sociocultural factors (Rosenzweig & Wigfield, 2017; Yeager & Walton, 2011). To put it another way, Rosenzweig & Wigfield (2017) and Yeager & Walton (2011) imply that sociocultural factors play a very important role in shaping motivation. In this sense, in the case of Bintara TNI AD and pro-organizational behavior, the sociocultural background of each individual who intends to join the Army is expected to encourage him/her to develop a positive motivation. Concerning this view on sociocultural factor and motivation, the first hypothesis that this article attempts to address is:

H1: Sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI AD members’ motivations

The influence of sociocultural factors on motivations

Sociocultural factors have a bigger power in a society and culture which has a significant influence over its members’ mind, feeling, and behavior. A research by Briner (2000) reveals that sociocultural factors can shape students’ experiences in their process of improving their knowledge in their field of study and developing their skill set. This research, as mentioned earlier, is aware of the different sociocultural backgrounds of Bintara TNI AD members and believes that these backgrounds will shape their achievement goals as a soldier. This means that factors like family, social class, culture, reference group, patriotism, and selfactualization are influential in shaping their goals when they become TNI personnel. In view of this perspective, the second hypothesis that this research proposes is:

H2: Sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI AD members’ achievement goals

The influence of sociocultural factors on motivation

Individuals who have an intrinsic motivation tend to participate in various activities and are capable of enjoying all activities at their workplace. Those with the ability to develop a self-motivation can create an enjoyable work environment for themselves and their colleagues. Thus, we assume that a soldier who enjoys their work may feel motivated to help their coworkers and to help to build a work climate that is conducive to the principles of proorganizational behavior (Barbuto & Scholl, 1999; Barbuto et al., 2000). Recent studies on this area have proven that motivation has a significant influence on pro-organizational behavior. Sources of motivations such as prestige perception, distinctiveness, and social satisfaction can directly help develop and reinforce pro-organizational behavior (Ibrahim & Aslinda, 2013). Soldiers may be motivated by prestige perception, distinctiveness, and social satisfaction, all at the same time, and may tend to feel encouraged to engage in proorganizational behavior.

H3: Motivation has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD Members’ pro-organizational behavior.

The influence of goal on pro-organizational behavior

The behaviors of an organization’s members have a significant influence on the organization’s success. It is evident, for example, in the US Army case. The US Army could benefit from its members’ supportive behaviors such as retention, positive WOM, and sacrifice. People are likely to develop a behavior that enables them to achieve their goals (Fishbach & Ferguson, 2007). The more an individual act to achieve a particular goal, the more their mind is drawn to the kind of behavior that support it; and the more the behavior shows its positive value, the more the individual is motivated to engage in a proorganizational behavior.

H4: Goal has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD members’ pro-organizational behavior.

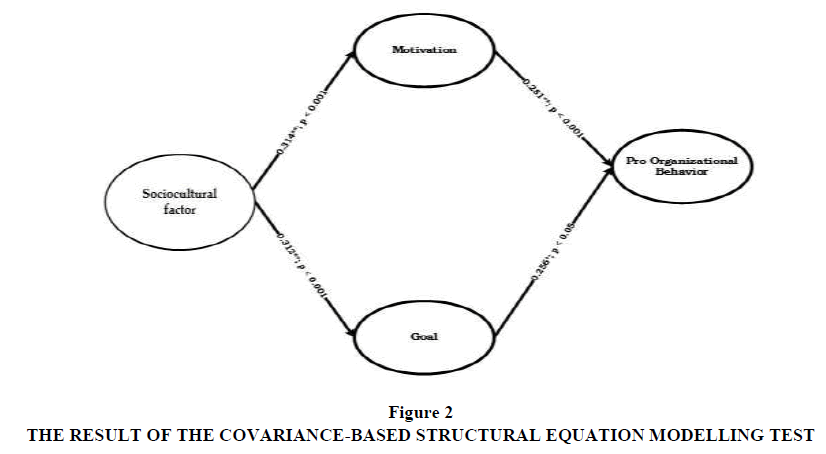

From the above-presented literature review and hypotheses, we propose the following research model as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Research Model On The Influence Of Sociocultural Factors Towards Motivations, Goals, And Pro-Organizational Behavior.

Methodology

Population and Sample

The population for this research includes all Bintara TNI-AD individuals that come from Papua, Maluku, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan. Since the formula for the determination of sample size cannot be used for non-probability sample, the determination of non-probability sample size is usually based on either the researchers’ subjective assessment or a comparative assessment of previous studies (Hair et al., 2014). In the present research, we determined the sample size according to a comparative assessment of the methods of measuring transformational leadership and pro-organizational behavior in military organizations presented in the previous studies. From this comparative assessment, this research determined that the minimum sample size was 64 and the maximum one was 3000 (Ivey & Kline, 2010; Arnold & Loughlin, 2013; Swid, 2014; Masal, 2015). In addition to the comparative assessment, the determination of sample size in this research was closely related to the use of SEM as an analysis tool. There has not been a clear-cut guidance on the determination of sample size in the application of SEM analysis. Hair et al., (2014) suggest that the minimum sample size to use in SEM is 300 for which the number of constructs is seven or less. According to Aaker et al. (2013), the bigger the sample size, the better the results will be as this size range can reduce the sampling error. With this consideration, the sample size for this research is set at 700 respondents.

In relation to this matter, Sekaran (2003) recommends that the minimum sample size that a study needs to meet ranges from 30 to 500. Therefore, it would be relevant to sample 700 Bintara TNI-AD members from Sulawesi, Maluku and Papua for this research. The proposed research model involves four main constructs: sociocultural factors, motivation, goal and pro-organizational behavior. Each construct comprises more than three items to observe.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected through survey and questionnaire. A Likert scale was chosen to measure the responses to the questionnaire with 1 as the lowest value for ‘strongly disagree’ response and 5 as the highest value for ‘strongly agree’ response. Sociocultural factors were measured using the measurement items (six items) that had been developed on the basis of studies conducted by Gorman & Thomas (1991), Griffith & Perry (1993), and Griffith (2008) respectively. Motivation construct (three items) was measured using items that were developed by Mael & Ashforth (1992). Goal construct was measured according to the method developed by Woodruff (2017) which involves five items. Organizational behavior construct was also measured using five measurement items offered by Organ (1988) and Kohan & Mazmanian (2003). In sum, this study adopted a total of 19 measurement indicators. The collected data were subsequently analyzed using a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach using the IBM SPSS AMOS software.

Results and Discussion

A total of 700 copies of questionnaire were disseminated to the respondents, but only 676 of them were returned and valid for the analysis. It means that the percentage of responses obtained in this research was 96.57%. This percentage informs that the number of responses are adequate for analysis since it exceeds the minimum percentage for the given measurement procedure, 80%. As suggested by Aaker et al. (2013), the minimum quantity for the ideal response rate is 80% since it can minimize the non-response bias in the results of the research.

Table 1 above illustrates that the majority of the respondents in this research are male, married, between 20 and 25 years old, and high school graduates. Most of them have 6 to 10 years of work experience and a range of IDR1,000,001 – IDR2,500,000 of expenses.

| Table 1 Respondents Profiles And Characteristics |

||

|---|---|---|

| Profile | Number | Percentage |

| Gender Male Female |

676 0 |

100 0 |

| Age (year) < 20 20 – 25 26 – 30 31 – 35 > 35 |

128 247 184 117 0 |

18.93 36.54 27.22 17.31 0 |

| Marital Status Married Single |

367 309 |

55.02 45.71 |

| Levels of education SMA (High school) D3 (Associates degree) S1 (Bachelor’s degree) S2 (Master’s degree) |

314 232 130 0 |

46.45 34.32 19.23 0 |

| Length of work experience (year) 1 – 5 6 – 10 11 – 15 > 15 |

272 313 58 33 |

4.88 8.58 46.30 40.24 |

| Expenses (IDR) 0 – 1,000,000 1,000,001 – 2,500,000 2,500,001 – 5,000,000 5,000,001 – 10,000,000 More than 10,000,000 |

244 377 55 0 0 |

36.09 55.77 8.14 0 0 |

Validity and reliability tests

Table 2 demonstrates that all constructs possess good levels of validity and reliability. All measurement indicators for each of the constructs have the following value: factor loading > 0.5. This score indicates that the measurement constructs have a high level of discriminant validity. The values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) presented in Table 2 were derived using the following equation.

| Table 2 The Results Of Validity And Reliability Tests |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct (Cronbach Alpha) | Item | Factor Loading | AVE (Average Variance Extracted) | Composite Reliability |

| Sociocultural factors (0.896) | SB1 | .800 | 0.606 | 0.910 |

| SB2 | .853 | |||

| SB3 | .706 | |||

| SB4 | .813 | |||

| SB5 | .870 | |||

| SB6 | .594 | |||

| Motivation (0.858) | M1 | .582 | 0.717 | 0.922 |

| M2 | .692 | |||

| M3 | .877 | |||

| Goal (0.841) | G1 | .669 | 0.515 | 0.864 |

| G2 | .680 | |||

| G3 | .720 | |||

| G4 | .782 | |||

| G5 | .733 | |||

| Pro-Organizational Behavior (0.833) | OCB1 | .626 | 0.525 | 0.857 |

| OCB2 | .683 | |||

| OCB3 | .795 | |||

| OCB4 | .719 | |||

| OCB5 | .786 | |||

All of the AVE values in Table 2 are greater than 0.5, indicating that the convergent validity of all seven constructs is satisfactory (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 2 also contains Cronbach Alpha (CA) values derived from SPSS software and Composite Reliability (CR) values derived from the following equation.

The CA and CR values in Table 2 are all greater than 0.6. These results indicate that the constructs are highly reliable (Chin et al., 1995)

Structural model test

The data analysis in this research was carried out by applying covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using IBM SPSS AMOS. The results of the test are illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The first hypothesis, stating that sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI AD members’ motivations, has been substantiated. It is supported by CR significant values of 5.079 and standardized estimation values of 0.314 (see Table 3). These figures reflect the fact that the sociocultural factors have a positive effect on Bintara TNI-AD members’ motivations. In other words, Bintara TNI-AD members’ high motivations are associated with the accompanying sociocultural factors. The finding also confirms that sociocultural factors are positively correlated with an individual’s motivation. Rosenzweig & Wigfield (2017) and Bohórquez et.al. (2022) argue that social factors determine an individual’s motivation for the fulfillment of their needs. In this research, sociocultural factors have proven influential in shaping Bintara TNI-AD soldiers’ motivations. Each of Bintara TNI-AD members, with their own sociocultural background, develops their own motivation for becoming a TNI soldier. In this context, members of Bintara TNI-AD are motivated by their respective sociocultural aspects of their lives to join the TNI-AD as a Bintara.

| Table 3 The Results Of Sem Estimation And Hypothesis Testing |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed Research Hypotheses | Parameter estimation value, standardized regression coefficient | Critical Ratio (CR) = t | Direction | Hypothesis decision |

| H1: Sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI AD members’ motivations. | 0.314 | 5.079 | Consistent, positive | Supported |

| H2: Sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI-AD members’ achievement goals. | 0.312 | 4.450 | Consistent, positive | Supported |

| H3: Motivation has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD Members’ Pro-Organizational Behavior. | 0.281 | 3.204 | Consistent, positive | Supported |

| H4: Goal has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD Members’ Pro-Organizational Behavior. | 0.217 | 2.120 | Consistent, positive | Supported |

The second hypothesis, which postulates that sociocultural factors influence Bintara TNI-AD members’ achievement goals, has been confirmed since the value of its CR is 4.450 and the value of its standardized estimation is 0.312 (see Table 3). These figures indicate that the sociocultural factors have a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD members’ achievement goals. In other words, Bintara TNI-AD members’ achievement goals are influenced by sociocultural factors. The achievement goal theory posits that external factors such as social environments, both school and home environments, have a significant effect on an individual’s behavior (Ames, 1992). This research has proven that certain sociocultural factors have had a significant effect on the Bintara TNI-AD and played a role as an antecedent of their achievement goal orientations. This finding corresponds to Briner (1999) observation that sociocultural factors have proven capable of shaping students/learners’ experiences in their endeavors to develop their comprehension of the acquired knowledge and the complex skills they have learned. In short, sociocultural factors play an important role in students/learners’ achievement goals. Similarly, Latham & Locke (1991) and van Ede & Nobre (2023) suggest that goal is an individual’s inner representation of the desired outcomes and acts as a motivation behind the displayed behaviors. In short, goal is directly related to sociocultural factors, which in turn influence the behavior one exhibits (Latham & Locke, 1991; van Ede & Nobre (2023).

The third hypothesis, which predicts that motivation has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD members’ pro-organizational behavior, has been substantiated. The analysis of this hypothesis indicates that its critical ratio is significant (CR = 3.204) and its standardized estimation is 0.281 (see Table 3). These values are an indication that motivation has a positive influence on Bintara TNI-AD members’ pro-organizational behavior. Thus, it has been proven that the Bintaras’ pro-organizational behavior is the result of their motivation. In brief, this research has established that there is a correlation between motivation and pro-organizational behavior. It has also proven that pro-organizational behavior is motive-based (Ariani, 2012; Davila & Finkelstein, 2013; Buddu & Scheepers, 2022). Soldiers who engage in pro-organizational behavior rely on their leaders’ perception of their motives and expectations (Allen & Rush, 1998). In conclusion, the finding of this research corresponds to the theory of pro-organizational behavior that holds that proorganizational behavior contributes significantly to motivation.

The fourth hypothesis, which predicts that goal influences Bintara TNI-AD members’ pro-organizational behavior, has been confirmed. The CR is significant at 2.120 and the standardized estimation is at 0.217 (see Table 3). These figures reflect goal’s positive influence on Bintara TNI-ADs’ pro organizational behavior. Thus, it has been proven that Bintara TNI-ADs’ pro-organizational behavior is shaped by their goals. The goals of an organization’s members have a significant influence on the organization’s success (Fishbach & Ferguson, 2007; Rasool et al., 2022; Widarko & Anwarodin, 2022).

This research acknowledges that there are two categories of goals, namely intrinsic goals and extrinsic goals. In terms of intrinsic goals, the finding above reveals that there is a self-transcendence or altruism aspect in serving as a Bintara TNI-AD, which is responsible for the increase in the pro-organizational behavior of the Bintaras under study. Altruism is closely related to members’ contributions to their organization. In general, people with altruistic goal and drive tend to perceive that pro-organizational behavior is a kind of behavior that supports the organization’s goals. In line with this notion, this research has found that individuals who join the Army with the extrinsic goal of honing their military skills such as shooting, tank or APC driving, and parachuting will be more motivated to engage in pro-organizational behavior.

Conclusions

Overall, the research model in this article fills the gap in the notion of achievement goal theory. The findings have demonstrated that the predictor variables are able to understand, explain, and predict Bintara TNI-AD members’ pro-organizational behavior. The variables are the sociocultural factors, motivation, and goal. This research has addressed the fact that pro-organizational behavior is a complex phenomenon that has been rarely discussed in depth when using the achievement goal theory. It has proven that pro-organizational behavior can be explained through motivation and goal variables in conjunction with sociocultural factors that contribute to them. Accordingly, the findings presented in the previous section show that the sociocultural background of each Bintara TNI-AD is influential in shaping their motivation and goal and in turn encouraging them to engage in a good organizational citizenship behavior.

Implications

The findings of this research offer a recommendation for other organizations, including government, profit-, as well as non-profit organizations, regarding how to comprehend organizational citizenship behavior. In addition, they present insights into factors that play a role in shaping TNI-AD members’ organizational citizenship behavior. Last but not least, the findings are expected to be a valuable suggestion for stakeholders in the TNIAD’s organizational system concerning how to conceive the external factors that underlie Bintara members’ motivations and goals, as well as the importance of policies that encourage them to maintain their motivation to engage in a good organizational citizenship behavior.

Limitations

The present research has a number of limitations. First, it only involves one rank in the TNI (Indonesian National Armed Forces), i.e., Bintara TNI-AD (Indonesian Army Non- Commissioned Officer). The different characteristics of different ranks in TNI-AD will presumably lead to more varied findings in the research. Second, this research only focuses on Bintara TNI-AD members coming from Papua, Maluku, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan. Differences in respondents’ characteristics that come from the geographical factor limit the generalization of the findings to Bintara TNI-AD members from other areas in Indonesia. Finally, this research involves respondents from only one gender, that is, male. Therefore, respondents’ differences that are caused by gender difference will also limit the generalization of the findings to the female Bintara TNI-AD members.

References

Aaker, D.A., Kumar, V., Leone, R.P., & Day, G.S. (2018).Marketing research. John Wiley & Sons.

Allen, T.D., & Rush, M.C. (1998). The effects of organizational citizenship behavior on performance judgments: a field study and a laboratory experiment.Journal of applied psychology,83(2), 247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation.Journal of educational psychology,84(3), 261.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anderman, E.M., Urdan, T., & Roeser, R. (2003, March). The patterns of adaptive learning survey: History, development, and psychometric properties. InIndicators of Positive Development Conference, Washington, DC.

Ariani, D.W. (2012). Comparing motives of organizational citizenship behavior between academic staffs' universities and teller staffs' banks in Indonesia.International Journal of Business and Management,7(1), 161.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arnett, D.B., German, S., & Hunt, S.D. (2003). The Identity Salience Model of Relationship Marketing Success: The Case of Nonprofit Marketing.Journal of Marketing, 67, 105 - 89.

Arnold, K.A., & Loughlin, C. (2013). Integrating transformational and participative versus directive leadership theories: Examining intellectual stimulation in male and female leaders across three contexts.Leadership & Organization Development Journal,34(1), 67-84.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barbuto Jr, J.E., & Scholl, R. W. (1999). Leaders' motivation and perception of followers' motivation as predictors of influence tactics used.Psychological Reports,84(3_suppl), 1087-1098..

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barbuto Jr, J. E., Fritz, S. M., & Marx, D. (2000). A field study of two measures of work motivation for predicting leader's transformational behaviors.Psychological Reports,86(1), 295-300.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bolino, M.C., Klotz, A.C., Turnley, W.H., & Harvey, J. (2013). Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior.Journal of Organizational Behavior,34(4), 542-559.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Briner, R.B. (2000). Relationships between work environments, psychological environments and psychological well-being.Occupational medicine,50(5), 299-303.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Buddu, A., & Scheepers, C.B. (2022). CSR and shared value in multi-stakeholder relationships in South African mining context.Social Responsibility Journal,18(2), 368-387.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Covington, M.V. (2000). Goal theory, motivation, and school achievement: An integrative review.Annual review of psychology,51(1), 171-200.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Davila, M.C., & Finkelstein, M.A. (2013). Organizational citizenship behavior and well-being: Preliminary results.International Journal of Applied Psychology,3(3), 45-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

de Geus, C.J., Ingrams, A., Tummers, L., & Pandey, S.K. (2020). Organizational citizenship behavior in the public sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda.Public Administration Review,80(2), 259-270.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J.M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis.Journal of personality and social psychology,70(3), 461.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fishbach, A., & Ferguson, M.J. (2007). The goal construct in social psychology.Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles,2, 490-515.

Friedel, J.M., Cortina, K.S., Turner, J.C., & Midgley, C. (2007). Achievement goals, efficacy beliefs and coping strategies in mathematics: The roles of perceived parent and teacher goal emphases.Contemporary Educational Psychology,32(3), 434-458.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gorman, L., & Thomas, G.W. (1991). Enlistment motivations of army reservists: Money, self-improvement, or patriotism?.Armed Forces & Society,17(4), 589-599.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Graham, J.W. (1991). An essay on organizational citizenship behavior.Employee responsibilities and rights journal,4, 249-270.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Griffith, J. (2008). Institutional motives for serving in the US Army National Guard: Implications for recruitment, retention, and readiness.Armed Forces & Society,34(2), 230-258.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Griffith, J., & Perry, S. (1993). Wanting to soldier: Enlistment motivations of Army Reserve recruits before and after Operation Desert Storm.Military Psychology,5(2), 127-139.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair Jr, J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research.European business review,26(2), 106-121.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ibrahim, M., & Aslinda, A. (2013). Relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) at government owned corporation companies.Journal of Public Administration and Governance,3(3), 35-42.

Ivey, G.W., & Kline, T.J. (2010). Transformational and active transactional leadership in the Canadian military.Leadership & Organization Development Journal,31(3), 246-262.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Latham, G.P., & Locke, E.A. (1991). Self-regulation through goal setting.Organizational behavior and human decision processes,50(2), 212-247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification.Journal of organizational Behavior,13(2), 103-123.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Masal, D. (2015). Shared and transformational leadership in the police.Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management,38(1), 40-55.

Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., & Middleton, M. (2001). Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost?.Journal of educational psychology,93(1), 77.

Organ, D.W. (1988).Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington books/DC heath and com.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Organ, D.W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It's construct clean-up time.Human performance,10(2), 85-97.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pintrich, P.R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement.Journal of educational psychology,92(3), 544.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pintrich, P.R., Conley, A.M., & Kempler, T.M. (2003). Current issues in achievement goal theory and research.International Journal of Educational Research,39(4-5), 319-337.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Podsakoff, N.P., Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Maynes, T.D., & Spoelma, T.M. (2014). Consequences of unit?level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research.Journal of Organizational Behavior,35(S1), S87-S119.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Raabe, J., Zakrajsek, R. A., Orme, J. G., Readdy, T., & Crain, J. A. (2020). Perceived cadre behavior, basic psychological need satisfaction, and motivation of US Army ROTC cadets: A self-determination theory perspective.Military Psychology,32(5), 398-409.

Rasool, S.F., Chin, T., Wang, M., Asghar, A., Khan, A., & Zhou, L. (2022). Exploring the role of organizational support, and critical success factors on renewable energy projects of Pakistan.Energy,243, 122765.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosenzweig, E.Q., & Wigfield, A. (2016). STEM motivation interventions for adolescents: A promising start, but further to go.Educational Psychologist,51(2), 146-163.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shih, S.S. (2005). Role of achievement goals in children's learning in Taiwan.The Journal of Educational Research,98(5), 310-319.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Smith, C.A. O.D. W. N. J.P., Organ, D.W., & Near, J.P. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents.Journal of applied psychology,68(4), 653.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Srivastava, S., & Madan, P. (2022). Linking ethical leadership and behavioral outcomes through workplace spirituality: a study on Indian hotel industry.Social Responsibility Journal,19(3), 504-524.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Swid, A. (2014). Police members perception of their leaders’ leadership style and its implications.Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management,37(3), 579-595.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van Ede, F., & Nobre, A.C. (2023). Turning attention inside out: How working memory serves behavior.Annual Review of Psychology,74, 137-165.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Weisman, H., Wu, C.H., Yoshikawa, K., & Lee, H.J. (2023). Antecedents of organizational identification: A review and agenda for future research.Journal of Management,49(6), 2030-2061.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Widarko, A., & Anwarodin, M.K. (2022). Work motivation and organizational culture on work performance: Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) as mediating variable.Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management,2(2), 123-138.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Woodruff, T.D. (2017). Who should the military recruit? The effects of institutional, occupational, and self-enhancement enlistment motives on soldier identification and behavior.Armed Forces & Society,43(4), 579-607.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yeager, D.S., & Walton, G.M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic.Review of educational Research,81(2), 267-301.

Received: 22-June-2023, Manuscript No. JLERI-23-13720; Editor assigned: 12-June-2023, Pre QC No. JLERI-23-13720(PQ); Reviewed: 27-June-2023, QC No. JLERI-23-13720; Revised: 15-July-2023, Manuscript No. JLERI-23-13720(R); Published: 28-July-2023