Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 2

The Role of Education towards Shaping Private Sector Employment: A Case from the Kingdom of Bahrain

Abstract

Private sector employers continue to resist employing nationals despite the nationalization strategies implemented by the Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC) to increase national labor participation. The paper explores private sector employers’ resistance in the GCC to employ nationals by reviewing current literature review. The resistance is evident through the literature review explored in GCC countries like Oman, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. The resistance of private sector employers merits further investigation as private sector employers play a crucial role in nationalization strategies implementation. The literature review reveals a need to address change processes directed to overcoming the resistance by private sector employers. The paper explores private sector employers’ view towards national labour participation, specifically in the Kingdom of Bahrain owing to the lack of published research about Bahrain national participation in the labour market “Bahrainization”. The study is conducted through a qualitative methodology of conducting semi-structured interviews with private sector managers and government officials. The data reveals that the lack of co-ordination with education and training with labour market needs does not form nationals as employees of choice in Bahrain.

Keywords

Nationalization, Bahrainization, Culture, Education, National Labor Participation.

Introduction

Several factors determine private sector employers’ view of national employment in the Gulf Corporation Countries. The factors of employers resistance towards national employment includes compensation, business skills, retention, flexibility, communication skills, culture, education, government sector preference (Forstenlechner et al., 2012; Nelson, 2004; Al-Ali, 2008; Al-Dosary & Rahman, 2005; Harry, 2007; Mellahi, 2000). Though there is extensive literature review on employers’ resistance in the GCC the current paper explores one factor that is education to analyze and explore the factor in depth.

Literature Review

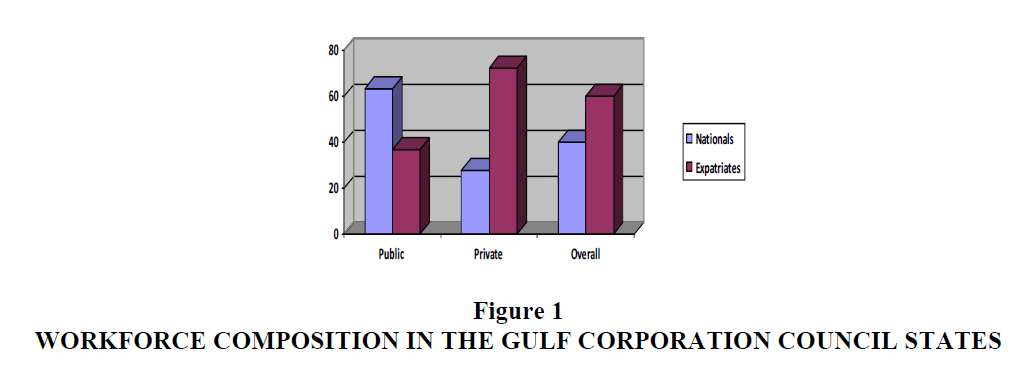

Even though GCC countries have worked on their education system, the investment in human capital has failed to yield high economic returns owing to the nationals’ expectations of working in the government sector that was ‘bloated’ (Al-Lamki, 1998). Harry (2007) argues that to create a large number of jobs in the private sector, GCC countries need an appropriate education system, suitable work ethic within the host population, and willingness on the part of employers to make a sustained and genuine effort to support and transfer skills, attitudes, and behaviours. Studies by other authors indicate a lack of coordination and planning between education (training and development) and labour market requirements, thereby forming a mismatch in the supply of labour in terms of skills and competencies required by the private sector (Al-Lamki, 1998; Al-Maskery, 1992; Rowe, 1992; Birks & Sinclair, 1980). Al-Lamki (2005) emphasizes that the government needs to ensure the development of a national cadre to face the challenges of globalization and a changing and competitive world by attaining a level of education and competence that is recognized internationally through holistic and integrated coordination and cooperation between the government and private sector employers and employees. Reinforcing Al-Lamki (2005) position, Godwin (2006) emphasizes that education needs to be responsive to the social and economic need of the UAE while engaging with the West. Educational systems are not adequately prepared to deal with the problem of reorienting traditional work values (Kapiszewski, 2006). Mellahi (2000) adds that to help train present and future employees, firms must either work closely with learning institutions in developing courses or need to take advantage of government learning credits for training nationals. Al-Lamki’s (1998), findings at the University of Sultan Qaboos revealed a noteworthy lack of awareness among Omanis about private sector employment opportunities coupled with the lack of a private sector recruitment campaign for Omani graduates. Ruppert (1998) concluded that providing training and education better attuned to the needs of the UAE and supporting trainees to find job rewards through cultural and value alignment could achieve the demographic balance that UAE society is seeking (Figure 1).

The below statistics indicate the importance of addressing nationalization as the figures indicate the lack of national employment participation in the private sector, despite the increase in universities in the GCC states. Yet, the graduates have a high preference to certain jobs that does not meet the strategy of diversification in the GCC economies (Tables 1 and 2).

| Table 1: Number Of Universities In Gcc Countries For Four Academic Years | ||||

| GCC STATE | 2001/2002 | 2002/2003 | 2003/2004 | 2007/2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahrain | 8 | 9 | 10 | 15 |

| Kuwait | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Oman | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Qatar | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 8 | 8 | 11 | 25 |

| UAE | 8 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Total | 37 | 39 | 44 | 73 |

Source: Adapted from Abouammoh (2009).

| Table 2: Share Of National Workers In Private Sector Employment In The Gcc In 2003 | |

| GCCSTATE | Total % national workers |

|---|---|

| Oman | 48% |

| Saudi Arabia | 46% |

| Bahrain | 30% |

| Kuwait | 3% |

| Qatar | 3% |

Source: Al-Kibsi et al. (2007) in Edwards (2011).

According to the solution to nationalizing positions in the GCC developing states requires building a capable indigenous workforce through education while changing expectations, as well as creating new worthwhile jobs for citizens. The GCC countries have succeeded in supporting education as Table 1 indicates the growth in developing universities. The GCC countries have developed the training sector to develop human resources. For example, focusing on developing human resources through vocational programmes in banking and finance and telecommunications engineering have successfully contributed to the achievement of the government’s Emiratization targets for the banking and telecommunications industries in the UAE (Wilkins, 2002). The sixth national five-year plan in Oman, covering the period 2001-2005, reflected the importance of human factors in Oman’s national strategic development process (Budhwar et al., 2002). One of the main aims of the ‘Oman 2020 strategy is to develop human resources and upgrade the skills of the Omani workforce throughout all sectors through education and training). The Omani government continues to fund higher education in order to develop local professional and technical expertise as it emphasizes recognition of the private sector as a vehicle for growth (Al-Hamadi et al., 2007; Ghailani & Khan 2004). Mellahi (2000) indicates that the success of the national human resources in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia can be achieved through creating a pool of skilled, disciplined and productive national workers through vocational education to generate both the quantity and quality of skills required to decrease dependency upon expatriates. However, vocational education cannot be considered as a ‘magic cure’ to meet the demands of the economy, which as well as measures to reduce unemployment by providing individuals with employable skills requires an adjustment of attitudes towards blue collar-work (Middleton, 1998; Middleton & Ziderman, 1997).

The serious challenge of human development plans in Saudi Arabia is to achieve harmony between the content of educational training programmes and an economy that is increasingly driven by competition, information and knowledge, particularly in scientific and technical areas, thereby establishing a link between macro development aspects (strategies, plans and policies) and micro development aspects (organization change and development) (Achoui, 2009). The Saudi government is aware of current trends at the national and international levels, which call for a response to emerging challenges especially in the development of human capital, which has led to revisions in education curricula, job-training practices and other human development policies to upgrade individuals’ competencies (Saudi Government, 2002). The challenges of Saudization puts more pressure on the private sector to spend more money on HRD through different methods, such as ‘on-the-job’ training programmes and professional training programmes in the training and development centres that are ‘mushrooming’ across the country (Achoui, 2009). However, Winckler (2009) finds that many companies in Saudi Arabia admitted they lack the experience to train and supervise Saudi workers. Even though training institutes are increasing, workplace training must raise its own bar to achieve quality standards and underscore the cultural values required of organizations by new recruits to avoid recruits being demoralized to the point where they leave their positions permanently (Jones, 1997).

Nationalization Requires Education that Includes

The development and unleashing of human expertise for multiple learning and performance purposes, individual, family, community, organization, nation, region and globe. National human resource development must be nationally purposeful and therefore formulated practiced and studied for the explicit reason of improving the economic, political and sociocultural well being of a specific nation and its citizens (Cunningham & Lynham, 2006).

Reviewing the various sources in the literature review, it is strongly evident that education plays a role in shaping nationals towards employment for private sector. The research examines the above views in the context of Bahrain owing to the lack of studies about “Bahrainization” in western literature.

Research Methodology

The research implements a qualitative methodology through interviews. Five to eight managerial level interviews were conducted in seven private organizations in the Kingdom of Bahrain, totaling to 38 interviewees. Managers in the private sector form a level of resistance that deserves in-depth analysis as discussed in the various literature reviews as indicated above. The private sector managers interviews were conducted in the below organizations.

The data was collected from October 2012 until April 2013 in the Kingdom of Bahrain by visiting the organizations and conducting the interviews after their approval and consent with the managers.

| Private Sector Organization | Bahrainization |

|---|---|

| Gulf Petrochemical Industrial Company | 90% |

| Gulf Hotel | 31% |

| Arabian Pearl Gulf School | 45% |

| Movenpick Hotel | 27% |

| Jawad Group | 50% |

| Kanoo Group | 63% |

| Dnata Travel | 20% |

Data Findings

Private sector managers in Bahrain point towards nationals’ resistance towards national employment owing to their characteristics; they are frequently described as ‘complainers’ or as lacking ‘commitment’, ‘dedication’, and being ‘proactive’ in work. In addition, private sector managers express their concern with nationals’ desire to move towards the government sector after employment. Private sector interviewees blamed education for shaping nationals in terms of knowledge, skills and abilities that do not meet business needs.

Private sector managers explain that education in Bahrain has not prepared individuals for the workplace and does not meet market needs. Education has been identified several times by managers interviewed as an important aspect that has failed to develop nationals for the economy’s needs. Education was criticized by a majority of the interviewees for failing to shape nationals for the workplace. Furthermore, there is a need to prepare individuals for vocational jobs as the economy moves towards dependence on technical and vocational competencies.

The interview data reveals that Bahrainis’ lack of skills and commitment partly owes to the mode of study they have gone through that lacks practical experience, business ethics and has specializations that are not aligned with the needs of the economy. There are several areas that managers recommended be improved in Bahrain’s educational system to develop Bahrainis towards business needs to develop the economy. Managers point towards the curriculum and mode of study that lacks creativity and business skills.

Managers realize that the curriculum and mode of study need to be strengthened for high caliber graduates. Graduates are not meeting job requirements reflecting the need to improve the curriculum and mode of education. The education nationals go through affects their productivity and quality of outputs at work. Education does not meet the standards for work required by private sector organizations. Curriculum improvement to upgrade the knowledge and skills of nationals is emphasized. The quotes from private sector managers below illustrate this analysis:

“Ministry of education needs to raise the standards of their curriculum”. (HR Manager)

“We are recruiting high distinction Bahraini graduates but their productivity is low owing to the education they have gone through in high school and university standards. This needs to be taken care of in Bahrain”. (Vice Principal)

“The challenge in Bahrainization is the shortage of chemical engineer people. There is a challenge in finding quality engineers. By quality, I mean strong basics of engineering skills. Bahrain University graduates generally are not good enough to meet and fit into our requirements”. (Superintendent)

Managers further discussed how education needs to meet the market requirements of the economy and generate graduates for challenging jobs. National graduates do not meet the needs of the economy in terms of jobs being generated in the areas of service, retail and hospitality as reflected by interviewee comments in these sectors:

“Education in Bahrain needs to be improved to meet market requirements”. (Acting Group HR Manager)

“Universities in Bahrain need to generate challenging jobs”. (Superintendent)

“Bahrain has improved but the world is changing, schools and universities need to keep up with market requirements, graduates need to be familiar to working and practical environments to be able to be competent nationals. Universities need to improve to meet economic requirements and schools have to set standards for market needs to bring in more responsible people to the market”. (Superintendent)

Apart from education not meeting market needs, on the basis of the interview data it is obvious that the educational mode has played a role in shaping the creativity and practical thinking skills of Bahrainis. It appears that education fails to instill skills that shape nationals for the actual work place.

“Bahrainis do not find creative ideas to improve their own work. This is the outcome of the education they have gone through. Most of our educational system in school focuses on memorization and learning thereby not allowing much room for creativity and talent. Talent is not appreciated in schools of Bahrain”. (Principal)

“Students need to have a practical and actual experience for work. From secondary school, they need to work and learn to get a flavor and sense of the real world”. (Superintendent)

Interviewees recommend improving education and development to support the sectors that the economy is diversifying into. The managers propose that education and training can play a role in tackling cultural issues by educating Bahrainis in the new sectors and their requirements. Hence, it is evident that education is a challenge that needs to be overcome to increase Bahrainization by improving its system to generate productive national labour for the economy. In sectors such as retail and hotels that have low Bahrainization, managers point to how the education system or training institutes were not effective in making Bahrainis aware of the benefits and value of such sectors. The analysis is supported by from different retail and service companies as shown in the quotes below:

“Government schools have not prepared us to work in the retail and service field”. (Divisional Manager)

“In summary in Bahrain the problems with the hotel industry employing nationals are the salary and training institutes. A training institute or college is required to instill values and culture of working in the hotel industry. I wish Bahrainis fill the position expats are being paid for BD1500-BD2000. We need to improve by advertising to nationals the future in the hotel. They need to understand this from the secondary school”. (HR Manager)

“Because culture is not supporting jobs in the hotels, we need Bahrainis to learn about sectors from an institute to clear the cultural barriers within the industry”. (Chief of Finance)

“For the travel industry to improve the government needs to introduce it in education to make them join the travel sector”. (Regional Manager)

The distinguishing challenge for Bahrain is that the population of young educated nationals has shown an increase in the numbers of Bachelor degree holders that are females. According to Ministry of Labor officials, creating jobs for national females is a challenge. Statistics for the year 2010 by the Central Informatics Organization in Bahrain indicate that the population of Bahrain is mostly made up of nationals within the age range of 10-24 where females and males. Government officials explain a critical situation that in previous years, unemployment used to lie within the uneducated national population, but the demographic has changed, and now the majority of unemployed are female Bachelor’s degree holders. According to 2013 data for job seekers whose unemployment case files have been dealt with by the recruitment office in the Ministry of Labor, there are 703 females bachelor’s degree holders compared to 164 males bachelor’s degree holders.

Discussion Of Findings

Despite the efforts to improve education in Bahrain, private sector managers criticized education in Bahrain, sharing the view with other GCC states that education forms a challenge towards Bahrainization in private sector. The interviewees emphasized that the challenge of education to meet labour needs persists, criticizing education’s failure to shape nationals for the workplace competencies of ‘communication’, ‘creativity’, ‘business ethics’, and ‘specializations’.

Private sector managers in Bahrain constantly mentioned the need for coordination of education with ‘market needs’ and ‘economic demands’. The Ministry of Education in Bahrain has a strategy to develop human resources by improving the education process through accessible, responsive, high quality education oriented services for the public. In its vision the Ministry:

“Seeks to develop a qualitative education system to reach a high degree of excellence and creativity. This vision emanates from the Islamic Religion lofty principles and values and the Kingdom of Bahrain's interaction with the human civilization and its Arab belonging to satisfy the requirements of continues development that conforms with the international standards, as stated in the Kingdom's constitution. Its mission is “to ensure the provision of evidence-bases education at all levels based on efficient use of ministry resources (Schools, libraries, e-services) and encouragement of personal responsibility for education”.

The Quality Assurance Authority for Education and Training was set up in 2008 with a vision to be “To be partners in developing a world-class education system in Bahrain”. The QAA is responsible for reviewing public and private schools, vocational training and higher education institutions, developing and implementing a national examination system for schools, and advancing Bahrain’s reputation as a leader in quality assurance in education, regionally and internationally.

Despite, governmental efforts exerted through the above ministries and authorities to develop local talent and create value added jobs for Bahrainis, the challenges of treating the economic and social costs of high unemployment, making Bahrainis employers’ first choice, developing Bahrainis to compete with expatriates persists. However, the low national labour participation rates raise questions about the education and human capital development efforts in Bahrain and in all GCC countries (Winckler, 2009).

The researcher strongly believes that the contradictory figures for education compared to the low national labour participation deserve further study and form an area of exploration to develop nationalization strategies that can benefit the GCC in the long term, allowing countries to utilize the investments made in national human resources to build capacity within their economies.

Despite education being criticized since 1990s, the challenge still remains as was mentioned extensively during interviews with private sector managers and government officials in Bahrain. Consideration of education within nationalization is thus demonstrated to be a necessity within a nationalization framework. Education prepares the supply of resources for the demand of the economy from an early age.

It is worth mentioning that Bahrainization strategies have worked differently from other GCC strategies in terms of moving towards changing cultural mindsets in work and building work ethics and competencies within nationals. In addition, it is worth noting that Bahrainis unlike other GCC countries prefer the private sector when the compensation is higher as indicated in a previous study (Alaali, 2018). Hence, Bahrain can strengthen its private sector when it its educational system meets needs of the private sector organizations. This shall cause educational investments to be gained into private sector as Bahrainis prefer to work in private sector when the compensation is higher (Al-Aali, 2018).

In addition, it is worth exploring government officials’ view towards education and its preparation for private sector employment or entrepreneurships projects that can strengthen the economy of Bahrain within the research findings for further exploration.

Conclusion

Examining Bahrain, the interviews provide evidence that education needs improvement to reduce the resistance towards private sector employers’ preference of foreign labour despite the nationalization strategies directed by the Kingdom of Bahrain. Similar to other GCC countries, Bahrain needs to coordinate education with market needs.

The research paper requires to analyze the educational systems in Bahrain and address the market gaps within the economy to enable provide a conceptual framework for implementation. Examining the factor of education towards shaping nationals for private sector employment through the interviews can be analyzed further through quantitative data for further validity and reliability of data explored.

References

- Abouammoh , A ( 2009). Higher education in Saudi Arabia: Reforms, challenges and priorities, Springer.

- Achoui, M. (2009). Human resource development in Gulf countries: an analysis of the trends and challenges facing Saudi Arabia', Human Resource Development International, 12(1), 35-46.

- Al-Aali, L (2018). Effectivenss of HRD in Private Sector: A case from The Kingdom of Bahrain, International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 4(8).

- Al-Ali, J. (2008). Emiratisation: drawing UAE nationals into their surging economy, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 28(9-10), 365-379.

- Al-Dosary, A. & Rahman, S. (2005). Saudization (Localization) -A Critical Review, Human Resource Development International, 8(4), 495-502.

- Al-Hamadi, A.B., Budhwar, S. & Shipton, H. (2007). Management of Human Resources in Oman, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), 100-113.

- Al-Kibsi, G., Benkert, C., & Schubert, J. (2007). Getting labor policy to work in the Gulf. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1-29.

- Al-Lamki (2005). The role of the private sector in Omanization: the case of the banking industry in the Sultanate of Oman, International Journal of Management, 22(2), 176-188.

- Al-Lamki, S. (1998). Barriers to Omanization in the private sector: The perceptions of Omani graduates, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(2), 377-400.

- Al-Maskery, M. (1992). Human Capital Theory and the Motivations and Expectations of University Students in the Sultanate of Oman. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri, St Louis, USA.

- Birks, J.S. & Sinclair, C.A. (1980). Arab manpower: the crisis of development, London: Croom-Helm.

- Edwards, B. (2011). Labour immigration and labour markets in the GCC countries: national patterns and trends, http://www2.lse.ac.uk/government/research/resgroups/kuwait/documents/Baldwin-Edwards,%20Martin.pdf.

- Forstenlechner, I., Madi, M.T., Selim, H. & Rutledge, E. (2012). Emiratisation: determining the factors that influence the recruitment decisions of employers in the UAE, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(2), 406-421.

- Ghailani, J.S. & Khan, S.A. (2004). Quality of secondary education and labour market requirement, Journal of Services Research, 4(1), 161-172.

- Godwin, S. (2006). Globalization, Education and Emiratisation: A study of the United Arab Emirates, The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 27(1), 1-14.

- Harry, W. (2007). Employment creation and localization: the crucial human resource issue for the GCC, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), 132-146.

- Jones, S. (1997). Localization Threat Forces Expats into Rear Guard Action, China Staff, October: 6-9.

- Kapiszewski, A. (2006). Arab versus Asian migrant workers in the GCC countries, Work 1051-9815.

- Lynham, S.A. & Cunningham, P.W. (2006). National human resource development in transitioning societies in the developing world: Concepts and challenges, Advances in Developing Human Resources, 8(1), 116-135.

- Mellahi, K. (2000). Human resource development through vocational education in Gulf Cooperation Countries: the case of Saudi Arabia, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 52(2), 329-344.

- Middleton, J. (1988). Changing Patterns of World Bank Investments in Vocational Education Schools, International Journal of Education Development, 18, 213-225.

- Middleton, J. & Ziderman, A. (1997). Overview: World Bank policy research on vocational education and training (Skills Training in Developing Countries: financial and planning issues), International Journal of Manpower, 18(1-2), 6-23.

- Nelson, C. (2004). UAE National Women at Work in the Private Sector: Conditions and Constraints, Labour Market Study No.20, Centre for Labour Market Research & Information (CLMRI), The National Human Resource Development and Employment Authority (Tanmia).

- Rowe, P.C. (1992). A Framework for a Human Resource Development Strategy. Support Paper for Oman HRD Conference. Muscat: Sultanate of Oman.

- Ruppert, E. (1998). Managing foreign labour in Singapore and Malaysia: are there lessons for GCC countries?, World Bank Report, World Bank: Washington D.C.

- Wilkins, S. (2002). Human resource development through vocational education in the United Arab Emirates: the case of Dubai polytechnic, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 54(1), 5-26.

- Winckler, O. (2009). Arab Political Demography, second edition, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Winckler, O. (2009). Labor and Liberalization: The Decline of the GCC Rentier System, in J. Teiterlbaum (ed.), Political Liberalization in the Persian Gulf. New York: Columbia University Press, 59-85.