Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 6S

The Rivalry between the west and Russia in Russia′s "Near Abroad": Perceptions, Interests and Strategies

Stefana Rafaela Erneanou, Aristotle University of Thessalonik

Citation Information: Erneanou, S.R. (2023). The rivalry between the west and russia in russia’s “near abroad”: perceptions, interests and strategies. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 26(S6), 1-09.

Abstract

This paper aims το present the underlying factors in the conflict between Russia and Georgia and the role played by the EU and USA. Firstly we briefly identify factors and policies that gradually escalated Western-Russian rivalry since 1990s. Then it will analyze how the political and economic balance achieved by Russia in the mid 2000 influenced its external politics. A main objective was to stop Georgia’s ambitions of further tightening its relations with the West, in particular its bid to join western organizations such as NATO. A particular emphasis will be placed on Russia’s strategy towards the so-called “de facto” states of the southern Caucasus, Southern Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Keywords

Western-Russian Rivalry, Political and Economic Balance, De Facto States, Georgia's Ambitions, Energy policy, Regional conflicts.

Introduction

The tension between the West and Russia has increased since the beginning of 2000, escalated in 2014 through the beginning of the Ukraine’s crisis and reaching its peak in 2022 with the burst of the Russian-Ukrainian War. This specific event should, however, be considered just the tip of the iceberg. Deeper reasons behind this tension had already appeared in the 1990s. The US and the EU, have also launched a multitude of policies, targeting the countries in Russia’s near abroad. In most of the cases these policies aimed for closer integration of these states into European political and economic structures, often at the expense of Russia’s interests. The advancement of the Eastern Partnership Program to the Association Agreement, was understood by Russia as a stepping stone to organizations such as NATO (Matsaberidze, 2015), whose eastward expansion was seen as a major threat to Russia’s influence in its near abroad and induces it to apply a spectrum of economy and security-related measures to steer them away from Western policies (Babayan, 2015).

In this regard, one of the most controversial issue has been the establishment of a post-cold war security system based on the extension of NATO in Europe, as well as US endeavor to dominate the international system. In many quarters of the globe, USA post-cold war policies have been perceived as arrogant and preoccupied with increasing American influence at the expense of state sovereignty or others’ great power vital interests. The collapse of the previous bipolar system delivered a major blow to Russia but boosted the US’s position in international affairs (Babayan, 2015). U.S. geopolitical culture largely processed the end of the Cold War as a victory for the policy of containment and for NATO’s steadfastness in front of the Soviet threat.

Initially, there were some discussions about the redundancy of NATO in the transformed security environment (Toal, 2017). However, these thoughts gave quickly way to the narrative of NATO as a transformed organization from a Cold War defensive alliance to that of “an inclusive alliance protecting the democratic states and open societies of the continent” (Baldwin & Heartsong, 2015). Clinton administration was searching for the successor doctrine that would replace cold war “containment” strategy. Finally, Anthony Lake, as then national security advisor, came up with the doctrine of “enlargement” (Lake & Morgan, 2010). He further stated that “In such a world, our interests compel US not only to be engaged but to lead”. “The successor to a doctrine of containment must be a strategy of enlargement of the world’s free community of market democracies”. Enlargement strategy was based on the idea that as long as “democracy and market economics hold sway in other nations, our own nation will be more secure, prosperous and influential, while the broader world will be more humane and peaceful” (Lake & Morgan, 2010). Enlargement justified the Clinton administration’s decision to expand NATO. It was one of many western polices that encroached on Russia’s historic interests (Toal, 2017). However, then Russian Minister Andrei Kozyrev clarified to US Ambassador Tom Pickering that only if Russia be accepted as the first post-Cold war state to join, it would not oppose NATO’s enlargement (Baldwin & Heartsong, 2015).

Early in the 1990s, there were clues that US was trying to prevent the emergence of any potential rival to the US’s hegemony by establishing a unilateral international system (Ambrosio, 2001). The notorious draft version of a document called the Defense Planning Guidance for 1994-1999 by Paul Wolfowitz, though revised by then Secretary of Defense, Dick Cheney and Colin Powell, signalized perceptions about American foreign policy interests. In one section of this draft the goal to prevent the emergence of a new rival either in the post-soviet union or elsewhere was declared, as well as the ability to undertake unilateral actions in case needed to protect US interest:

“While the United States cannot become the world’s policeman and assume responsibility for solving every international security problem, neither can we allow our critical interests to depend solely on international mechanisms that can be blocked by countries whose interests may be very different from our own”

“The third goal is to preclude any hostile power from dominating a region critical to our interests, and also thereby to strengthen the barriers against the reemergence of a global threat to the interests of the U.S. and our allies. These regions include Europe, East Asia, the Middle East/Persian Gulf, and Latin America. Consolidated, nondemocratic control of the resources of such a critical region could generate a significant threat to our security”.

For Russia unipolarity became an unacceptable state of affairs. NATO expansion, US missile attacks against Sudan, Afghanistan, and Iraq in the latter half of 1998, NATO’s bombing of Serbia in 1999 despite strong Russian opposition, attempts by the United States to gain influence in the southern tier of the former Soviet Union (Ambrosio, 2001) can be identified as some of the reasons why Russian policy makers came to support the establishment of a multipolar world as an alternative system to American unilateralism.

Consequently, after a brief period of Euro-Atlantic idealism at the beginning of Boris Yeltsin’s governance, Russian foreign policy in late 1992 began to be dominated by the need to maintain Russian influence in the post-Soviet space. One of the most important tasks of Russian foreign policy included regulating armed conflicts throughout the post-Soviet space, preventing their expansion into Russia, and protecting the rights of Russian-speaking populations in its near abroad (Lake & Morgan, 2010). Russian officials of that time were calling for the reintegration of newly formed post-Soviet republics into a structure where Russia would be allowed to continue to play its historic role (Lough, 1993).

The triad by means of which Russia were safeguarding the interests of its security in the 1990s in both the South Caucasus was military bases, defense of the CIS external borders, peacekeepers (Naumkin, 2002), with the aim to prevent the emergence of a political and power vacuum which could be exploited by western powers.

However, it was the political and economic instability during the 1990s that prevented Russian policy makers from actively pursuing their foreign policy interests. Russia, facing multiple political and economic crisis, found itself unable to prevent the expansion of western influence into regions traditionally identified with Moscow's critical security interests: these are East-Central Europe, the Balkans, South Caucasus and Central Asia.

This state of affairs has begun changing in the beginning of millennium, demonstrating a connection between internal changes within the Russian Federation and the development of a much more assertive foreign policy. The coherent and unified picture of Russian foreign policy towards the South Caucasus was also connected to a more assertive Russian attitude towards Georgia. This turnaround was qualified by a number of factors.

Firstly, the rise to power of Vladimir Putin, who in 1999 became the Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, put an end to the existence of multiple centers of power within the Russian Federation in relation to the North Caucasus. The power of oligarchs who possessed enormous economic and political influence during the 1990s, and who also represented a serious obstacle to the centralization of power in the hands of the president, was effectively broken. Putin also managed to push through the centralization of the Russian federal system and thus weakened existing local centers of power, creating seven Federal Districts headed by appointed representatives of the president (George, 2009).

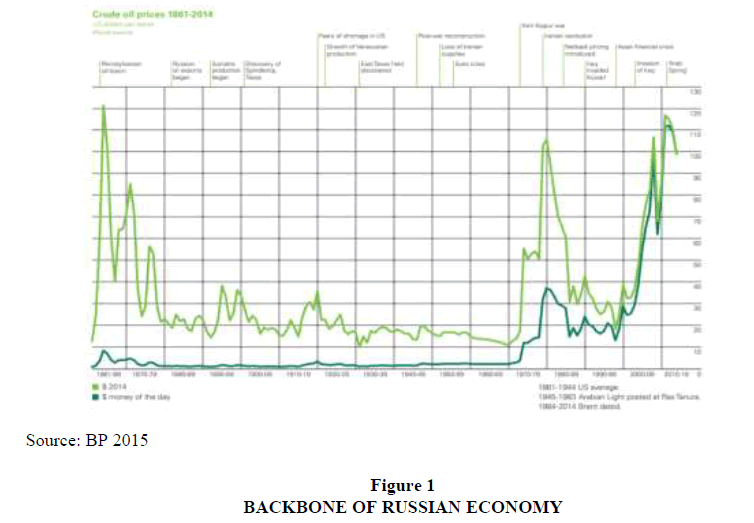

In parallel, there was a significant improvement in the Russian economy. During 1990s Russia experienced a decline in its GDP by 30% (Hoch et al., 2014). In the middle of decade 2000s the major inflow of cash was particularly the result of high oil and gas prices, which represent the backbone of Russian economy (Figure 1). Annual GDP growth of Russia maintained high rates during the decade of 2000s (Table 1 & 2).

| Table 1 Annual Gdp Growth Of Russia |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Russia | 10% | 5,1% | 4,7% | 7,3% | 7,2% | 6,3% | 8,2% | 8,5% | 5,2% | -7,8% | 4,5 |

Source: The World Bank Data.

Positive was also the raise of the Gross National Income (GNI), furthering social, political and economic stabilization process in Russia (Table 2).

| Table 2 Gross National Income (Gni) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| Russia | 1.710 | 1.780 | 2.100 | 2.580 | 3.410 | 4.450 | 5.800 | 7.560 | 9.590 |

Source: The World Bank Data.

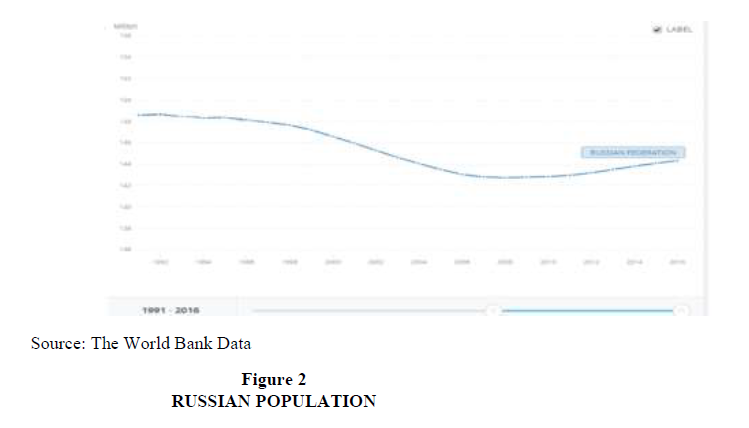

In the middle of this decade also, population decline came to an end, after several years of gradual reductions. In 1995 Russia numbered a population of 148.293.000, while in 2003 , 143.622.000 people. That means a decrease of approximately 5 million in just 8 years. Since 2007 this negative trend has been checked (Figure 2).

The overall stabilization influenced the foreign policy of Russia. A closer look into the official documents and statements at the beginning of the new millennium identifies a link between the increased output of the Russian economy and the growth in the foreign policy assertiveness of the Russian Federation. Russian president Vladimir Putin in his annual address to the Federal Assembly in 2004, underlined the beneficial impact of economic growth, political stability and strengthening the state on the international position of Russia. Next year he stated: ‘It is certain that Russia should continue its civilizing mission on the Eurasian continent’, adopting clearly a much more assertive political tone.

The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation of 2008 continued in the trend of greater involvement in foreign policy and the promotion of interests in the near abroad. ‘Russia will strive to build strong positions of authority in the world community that best meet the interests of the Russian Federation as one of influential centers in the modern world, and which are necessary for the growth of its political, economic, intellectual and spiritual potential’ “The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, 2008”. In addition, Russian objections regarding NATO expansion, particularly the inclusion of post-Soviet states, found expression in this official document: ‘Russia maintains its negative attitude towards the expansion of NATO, notably to the plans of admitting Ukraine and Georgia to the membership in the alliance, as well as to bringing the NATO military infrastructure closer to the Russian borders on the whole, which violates the principle of equal security, leads to new dividing lines in Europe and runs counter to the tasks of increasing the effectiveness of joint work in search for responses to real challenges of our time’ “The Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, 2008”.

Earlier in February 2008 Bush government had decided to promote Membership Action Plans (MAP) to Ukraine and Georgia in view of Bucharest NATO summit, as a first step towards the alliance. Germany and France opposed such an offer (Toal, 2017) the final declaration of this summit welcomed Georgia’s and Ukraine’s aspirations for membership in NATO. Nevertheless, nothing more than a vague promise for future acceptance could be offered to these states.

These remarks help us further the analysis and consider how the western factor influence Russian strategy in its near abroad, particularly in South Caucasus. Kremlin felt the need to assert its power over Georgia. Since the second half of the 1990s, the USA and the EU have begun to vigorously promote their economic interests in this area (Hoch, 2011). In 1994, a major oil contract was signed between Azerbaijan and ten major Western oil companies for exploring the Azerbaijani sector of the Caspian Sea. The agreement also included the building of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline to export Azerbaijani oil to Europe. In 1998, the US National Security Strategy argued for the full integration of certain areas of CIS into Western economic and political structures (Clinton, 1998). The U.S. support for the construction of this oil pipeline, one that was not considered by many oil companies as economically feasible, was interpreted by Moscow as contrary to Russia’s interests, that lay in directing the transit of oil via its territory (Naumkin, 2002). Moscow was not in favor of supporting the construction of pipelines for merely political purposes.

Rhetorically, the United States claimed that its energy policy in South Caucasus was determined by concern for diversity of supply as well as the need to decrease the dependence of newly independent states on Russia. In geostrategic terms, the United States sought to prevent any significant pipeline projects via Russian territory and to ensure that Caspian and Central Asian energy were transported to Europe bypassing Russia, via a western corridor of pipelines across states it considered friendly (Toal, 2017). Georgia’s strategic value has increased due to its geographical location.

Georgia’s pro-Western orientation exacerbated the rivalry. It can be considered as an additional parameter that leaded to the Russian-Georgian five-day war in August 2008. Georgian leaders tried to use greater cooperation with the West, as a way to balance the influence of Russia, which in the second half of the 1990s was considered the main cause of instability in the region (Devdariani, 2005).

In 1999, Georgia incited pressure for the withdrawal of Russian military garrisons from the country at a meeting of representatives of OSCE in Istanbul. Despite the agreement between the political leaders of Georgia and Russia and the latter’s commitment to remove its bases in Vaziani, Gudauta, Batumi, and Akhalkalaki, the process of evacuating Russian troops did not take place for a long time. Russia feared that the power vacuum could be replenished by US/ NATO forces. Until the arrival of Mikhail Saakashvili’s administration, the only base closed was Vaziani.

Among the incidents that escalated tensions in the region of South Caucasus was the arrival in Georgia of U.S. military advisors at the end of February 2002 to train Georgian Special Forces to more effectively confront terrorist and Chechen rebels in Pankisi Gorge region. From the Russian perspective, Georgia’s Train and Equip program (GTEP) was alarming not only because it signified Georgia’s tilt toward the West, but also because the decision of the Georgian government to accept U.S. military support was made after Georgia had repeatedly rejected Russia’s offer to cooperate in counterterrorism operations in the Pankisi Gorge (Nagashima, 2019).

Pro-western and especially pro-NATO attitude was further reinforced after the rise of Saakashvili as president of Georgia. Firstly, the way that he ascended to power in view of the so-called “Rose revolution” created convulsion in Kremlin. The latter perceives “color revolutions” as western instigated movements, aiming to provoke regime changes, favorable to western interests. The fact that foreign-funded nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) used to play a crucial role to instigate and organize protests in Tbilisi and elsewhere reinforces suspicions of western involvement. Consequently, Russia interpreted EU and US support for the wave of “colored revolutions” as a direct threat in its near abroad (Babayan, 2015). The Rose and Orange Revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine alarmed Moscow. These were the very first signals of the future eastward expansion of EU and U.S. interests (Matsaberidze, 2015).

Since the start of his leadership, Saakashvili vigorously pursued NATO membership. It is attested by plenty of references in various official documents. The “National Military Strategy of Georgia,” adopted in 2005, announced significant reforms in the defense sector with the aim of reaching NATO standards and achieving interoperability (National Military Strategy of Georgia, 2005). The document “Georgia’s Commitments under the Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP) with NATO: 2004–2006” openly stated: “Georgia is aware of the progress it needs to make prior to advancing its NATO membership aspirations (Georgia’s Commitments Under the Individual Partnership Action Plan). In the same document it was mentioned that frozen conflicts in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali Region (South-Ossetia) hinder the stable development of the country and that Georgian leadership should resolve them.

The resolution of this conflicts was also a prerequisite to further engagement with NATO. One of the criteria to acquire membership in NATO as stated in the Study on NATO Enlargement is the resolution of ethnic or territorial conflicts “States which have ethnic disputes or external territorial disputes, including irredentist claims, or internal jurisdictional disputes must settle those disputes by peaceful means in accordance with OSCE principles. Resolution of such disputes is a factor in determining whether to invite a state to join the Alliance”. The resolution of these conflicts was the main prerequisite for Georgia’s membership in NATO. Hence intervening and preserving the secessionist territories would bring Russia desired goals – to intercept western incursion into Russian sphere of influence and undercut Georgia’s pro-western aspirations.

Potential incorporation of Georgia and Ukraine in NATO or even EU, would mean that the so called “buffer zone” between Russia and the West will disappear and the military block will border Russia itself (Matsaberidze, 2015). Consequently, western expansion towards these regions is perceived by Kremlin as a major threat. Thus, the August War in 2008 between Georgia and Russia could be seen as a Russian attempt to stop Georgia’s aspiration to join NATO and the EU, or at least to transform it into a vague promise for the future. The main goal for Russia can be achieved by supporting de facto states in Georgia and Ukraine (Matsaberidze, 2015). It is vital to consider international competition as the main, or at least a significant cause of the Russian-Georgian war of August 2008 and the main source of instability in the Caucasus as a result of increasing competition both military and economically, between the United States and Russia (Matsaberidze, 2015).

As long as USA was trying to increase its influence in South Caucasus, Moscow had little interest in a resolution of these conflicts which could have allowed Georgia to proceed to the West even faster (Asmus, 2010). In order to avoid encirclement by NATO member states, Russia instrumentalized the two de facto independent states in South Caucasus: South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Russia successfully managed to securitize national minorities in its near abroad in service to its foreign policy interests. During 2000s protecting national minorities in Russia’s near abroad was consolidated as a basis of the national security concept upon being given passports: Russia will defend its citizens all over the world by any means necessary. The Kremlin tried to foil Georgia’s incentive to use military force to regain control over Abkhazia or South Ossetia by increasing dramatically the number of Russian citizens in these two respective de facto independent states and demonstrating its strong commitment to the region. On August 8, 2008, in his statement on the situation in South Ossetia, Russian president Dmitri Medvedev declared, “the majority of them [the victims of Georgia’s attack on South Ossetia] are citizens of the Russian Federation. As president of the Russian Federation it is my duty to protect the lives and dignity of Russian citizens wherever they may be”.

Conclusion

In conclusion, various developments in Russian-American relations as well as Russian-Georgian relations prompted concern that Georgian side having USA support, would try to regain control over the two de facto independent republics by force. In this context, Russia started passportization in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, in order to demonstrate its full commitment towards these two de facto states and to increase deterrence toward Georgia, with the aim of maintaining the status quo in these regions. Passportization in South Ossetia was launched as a reaction to the incorporation of the Adjara republic by Saakashvili administration in May 2004. In this case, too, Russia initiated passportization on the one hand to counter Georgia’s ambition to incorporate South Ossetia by force and on the other to forestall the NATO’s membership aspirations. Georgia and Ukraine are not Russia’s primary objectives; rather, they are tools for gaining leverage over the West. Passportization was implemented not for aggressive or expansionist purposes, but rather in a reactive way, to protect its sphere of influence when it was being threatened by western attempts to interfere in South Caucasus.

References

Ambrosio, T. (2001). Russia's quest for multipolarity: A response to US foreign policy in the post-cold war era.European Security,10(1), 45-67.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Asmus, R. (2010).A little war that shook the world: Georgia, Russia, and the future of the West. St. Martin's Press.

Babayan, N. (2017). The return of the empire? Russia’s counteraction to transatlantic democracy promotion in its near abroad. InDemocracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers. 68-88.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baldwin, N., & Heartsong, K. (2014).Ukraine: Zbig's Grand Chessboard & how the West was Checkmated. Tayen Lane.

Clinton, B. (1998). A national security strategy for a new century. White House.

Devdariani, J. (2005).Georgia and Russia: the troubled road to accommodation. na.

George, J. A. (2009). The Tragedy of the Rose Revolution. InThe Politics of Ethnic Separatism in Russia and Georgia,167-183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hoch, T. (2011). EU Strategy towards Post-Soviet De Facto States. Contemporary European Studies, (02), 69-85.

Hoch, T., Souleimanov, E., & Baranec, T. (2014). Russia’s role in the official peace process in South Ossetia.Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, (23), 53-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lake, D.A., & Morgan, P.M. (2010).Regional orders: Building security in a new world. Penn State Press.

Lough, J. (1993). Defining Russia's relations with neighboring states.RFE/RL Research Report,2(20), 53-60.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malek, M. (2008). NATO and the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia on Different Tracks.Connections,7(3), 30-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Matsaberidze, D. (2015). Russia vs. EU/US through Georgia and Ukraine.Connections,14(2), 77-86.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nagashima, T. (2019). Russia’s passportization policy toward unrecognized republics: Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria.Problems of Post-Communism,66(3), 186-199.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Naumkin, V.V. (2002). Russian policy in the South Caucasus.Connections,1(3), 31-38.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Toal, G. (2017).Near abroad: Putin, the West and the contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus. Oxford University Press.

Received: 24-July-2023, Manuscript No. JLERI-23-13909; Editor assigned: 25-July-2023, Pre QC No. JLERI-23-13909(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Aug-2023, QC No. JLERI-23-13909; Revised: 24-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. JLERI-23-13909(R); Published: 21-Aug-2023