Research Article: 2023 Vol: 29 Issue: 1S

The Retail Management Decisions of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises(MSMES) in times of Crisis

June Ann J. Casimiro, Saint Louis University

Leilani I. De Guzman, Saint Louis University

Citation Information: Casimiro, J.A.J., & De Guzman, L.I. (2023). The retail management decisions of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMES) in times of crisis. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 29(S1), 1-18.

Abstract

Micro, Small, and Medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) have the majority contributions to the Philippine economy, although they are prone to risk during an economic crisis like what the COVID-19 pandemic brought. This study focused on the retailing decisions of MSMEs, which are clustered into merchandise management and store management. With the pandemic’s impact,only the firm with effective adaptation to environmental changes will thrive, according to the Theory of Natural Selection. However, there are only limited studies in terms of analyzing what the MSMEs do in carrying out retail decisions in two different scenarios – pre-COVID-19 versus during COVID-19. This study's main objective is to describe MSMEs' retailing decisions. The researcher used a descriptive approach aided by quantitative techniques. A total of 174 respondents from the top municipality with registered MSMEs participated in this research. This study found that MSMEs are now shifting from brick-and-mortar to brick-and-click operations at the onset of a pandemic. However, generally speaking, there is not enough evidence to say that merchandise and store management change when the pandemic hits the country. Nevertheless, a number of ways in performing these decisions have been developed and improved. Also, MSMEs' perception of the importance of merchandise and store management strategies significantly changed. This led to the proposal of the retail decisions model, which might help contribute to the body of knowledge of marketing and in business in general.

Keywords

Retail, Merchandise Management, Store Management, COVID19, MSMEs.

Introduction

Micro, Small, and Medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) are the majority of businesses in the Philippines, with a 99.5% market share (Department of Trade and Industry, 2020). The MSMEs are frequently denoted as the lifeblood of the country's economy. In fact, they have employed 63% of the Philippine workforce (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020). Although considered the lifeblood of the Philippine economy, they are also one of the most at risk during economic recession and/or crises (Bartik et al., 2020; Karr et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2015).

According to DTI, most MSMEs are engaged in wholesale and retail trade, with 46.2%. Hence, this study focused on the retailing activities of MSMEs that add value to the products being sold.

Retail management decisions start from understanding the environment of retailing in which the business operates—followed by the formulation of retail strategies up to the decisions about putting the strategy into action and gaining long-term competitive advantage—which Levy et al. (2014) clustered into merchandise management and store management.

Merchandise Management

Merchandising philosophies are the foundation for making decisions about managing the inventory, including products to carry, shelf space allotment, inventory turnover, pricing, stock control, etc. In merchandise management (Levy et al., 2014), the retailer attempts to offer the appropriate quantity of the right merchandise in the right place and at the right time to meet the business' financial goals. This encompasses the planning, buying, and selling of merchandise. As such, some retail companies' merchandise management comprises selecting necessary merchandise, selling slow-selling products, researching the best supplier and negotiating with them (Park & Park, 2003).

In the study of Kakkar (2016) merchandise planning has numerous factors, such as forecast, innovativeness, assortment, brands, timing, allocation, and replenishment. Meanwhile, the study by Park and Park (2003) mentioned that management's three significant merchandise functions include demand forecasting, purchasing, and evaluating and selecting. Mou et al. (2018) state that demand estimation is the foundation of retail store operations. Many factors influence demand, like customer preferences, promotions, seasonality, and holidays. Inventory management can impact business performance. Inefficient management of inventory may result in lost sales. Small businesses' inventory management techniques include first in, first out (FIFO), first expired, first out (FEFO), just-in-time inventory, economic order quantity, and the like.

Additionally, the retailer's determination of innovativeness of merchandise plans includes how conservative or innovative target markets are, what are the products or services growth potential, what are retailer's image, should the business lead or follow the competition, what are the customer segments, how responsive the business is to their consumers, how large amount of investment to consider, how good the plans are, how much risks these have (Kumar, 2007).

In assortment plans, it tells the breadth and depth of merchandise to offer in a merchandise category. The goal of assortment planning is to specify an assortment that maximizes sales or gross margin while taking into account various constraints such as a limited budget for product purchases, limited shelf space for displaying products, and a variety of other constraints (Kök et al., 2008).

When considering merchandise management, it is good to note that brands are a part of assortment planning; hence, it is important to know the proper mix of brands, such as national or manufacturer's brand, where it is designed, produced, and sold to multiple retailers; store or private brand that the retailers develop; and generic brands that are labeled or named as the commodity itself (Levy et al., 2014). Timing is another factor in merchandising planning where the retailers must decide when the merchandise is to be stocked. To correctly plan the timing of the merchandise, the retailer must consider its forecasts and numerous other influences such as peak seasons, order and delivery time, stock turnover, discounts, and inventory procedure efficiency (Kumar, 2007). Allocation is also essential to merchandise planning since it determines the merchandise assigned in a specific store.

Retailers use two main pricing strategies: high or low pricing and low price regularly. In theory, businesses maximize profits by establishing prices based on client price sensitivity and merchandise cost (Levy et al., 2014). However, typical businesses set the price according to costs and add a markup. Other pricing strategies include price skimming, market penetration, premium pricing, economy pricing, etc. The emergence of alternative payment mediums such as digital payments and electronic fund transfers also exists.

Store Management

According to Mou et al. (2018), the physical design of a retail store is usually comprised of a customer-facing shop floor and an operationally-focused backroom area. The three critical elements in retail operations are the customers, store personnel, and products.

Store operation decisions include assortment and display, in-store logistics, employee management, product promotion, and checkout operations (Mou et al., 2018a). Most of the published research (Kök & Fisher, 2007; Mantrala, 2009) found that the primary concerns in assortment and display are the breadth and width of the products to stock and the shelf allocation in terms of the arrangement of goods in the shelves. Employees are one of the organization's important assets in performing such functions. Thus, matching store personnel and customer demands are of utmost importance in retail stores' performance. Store personnel converts customer traffic to sales.

One of the factors that can be looked into in store management is product promotion which includes price discounts, coupons, free products, gifts, advertising, displays, and features whole activities such as trade promotion and rebates, etc. are mostly planned with suppliers. Most retailers use promotions to boost sales and increase customer loyalty. However, Cheungsuvadee (2006) pointed out that small retailers have limited resources and mostly rely on word-of-mouth, local events, and sponsorship compared to large retailers. As a result, smaller businesses can customize their service delivery to better compete against huge one-stop shops. This could explain why the in-store promotion has such a significant impact on SMRs' business performance. Checkout operation plays a vital role in the overall customer shopping experience—such as speed and how approachable employees are. The queuing theory also covers this factor of store operations (Mou et al., 2018). However, emerging services, including self-service lanes and mobile checkouts, are getting attention in retail operations.

Basically, merchandise management entails decisions on understanding and evaluating the purchasing habits of consumers in order to effectively source, plan, display, and stock merchandise (Park & Park, 2003). In comparison, store management focuses on the decisions made by store personnel (Levy et al., 2014).

During the pandemic, retailers evaluated their strategies to keep up with the competition. Here, the theory of natural selection outlined by Charles Darwin in 1859 and was first used by Dreesman in retailing (Madaan, 2009) is deemed relevant. This theory states that adaptation to environmental changes is vital for the survival of retail formats.

According to the American Marketing Association, it is not only to adapt to environmental changes but to effectively adapt to thrive in business. It is also referred to as the "survival of the fittest" (Brooks, 2008). With this, it is important to know what Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSME) do to stay in business amidst and even after the pandemic. An analysis of the emerging retail decisions in the new normal has to be explored. However, there are only limited studies in terms of analyzing what the MSMEs do in carrying out the merchandise management and store management marketing strategies in two different scenarios – pre-Covid versus during Covid. Hence, this study will fill in the gap by studying emerging retail decisions in times of crisis.

General Objective of the Study

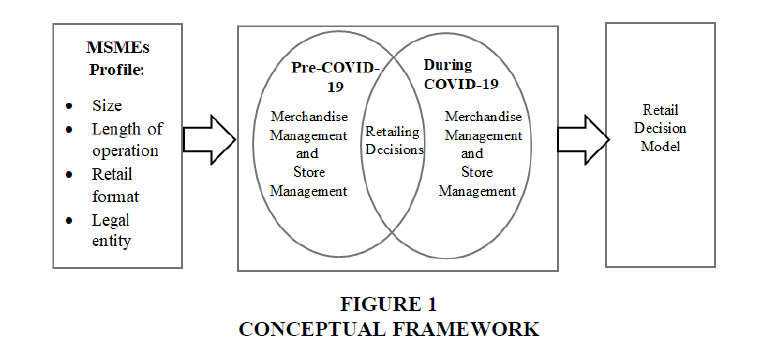

The main objective of this study is to describe the retailing decisions of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, particularly the changes in retailing decision strategies employed to stay in business despite the turbulent environment caused by Covid19, and determine the socio-economic effect of COVID 19 to MSMEs. As based on the theory of natural selection in retailing, only the firms with effective adaptation to environmental changes will thrive (Brooks, 2008)(Figure 1).

The MSMEs profile includes micro, small, and medium enterprises, length of operation, retail format, and legal entity. Moreover, the MSMEs' retailing decisions are clustered into merchandise management and store management in pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19. The expected output in the association between pre-Covid19 and during Covid19 along the merchandise management and store management is the retailing decision model in times of crisis.

This sought to answer the question, what are the retailing decisions of MSMEs in terms of merchandise management and store management before and during the Covid19? In response, the following hypotheses were addressed:

H1: There is a significant difference in the strategies implemented between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 in terms of merchandise management.

H2: There is a significant difference in the strategies implemented between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 in terms of store management.

H3: There is a significant difference in the perceived importance of merchandise management strategies between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19.

H4: There is a significant difference in the perceived importance of store management strategies between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19.

Methodology

Research Design

The researcher used a descriptive approach aided by quantitative techniques. It is the applicable design for a research study that describes the characteristics of the assessed data obtained from the survey, (Cheungsuvadee, 2006).

Population of the Study

The participants in the study are the managers or owners of the MSMEs in Talavera, Nueva Ecija, due to limited mobility caused by government restrictions. This area is the top one in terms of registered MSMEs in the province. In the case that the owner is not available, their chosen representative takes over. A total of 314 MSMEs were identified. The computed sample using slovin's formula is 174 with a 5% margin of error. The respondents were chosen using simple random sampling. Included participants are those businesses that have been in operation for not less than five years, with a retail format of groceries and general merchandise, and have a legal entity of sole proprietorship and partnership. According to Pantano et al. (2020), grocery stores will be seen as vital members of society, and their employees will be regarded as essential workers. The established businesses in less than five years were excluded as participants. In addition, according to the list from DTI, the majority of the registered MSMEs fall under the sole proprietorship and partnership legal entity.

Research Instrument

Online and offline surveys to collect the data were used depending on the government restrictions and the ability of the respondents to answer the questions. The survey questionnaire has six sections. Section one is the business profile; sections two to five include the questions for merchandise management and store management divided into pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, using the rating scale on the level of importance and frequency. Some questions were lifted from the study of Kakkar (2016); section six includes the supplemental questions that are mostly lifted from the study of Cheungsuvadee (2006).

The experts in the field did the validity test in the field. Pilot testing was employed on ten respondents as advised by the statistician and as mentioned by Isaac and Michael (1995), Saunders et al. (2016), and Fink (2013). The researcher facilitated the pilot testing and conducted it on MSMEs in the nearby town, which were not included in the respondents. As for the Reliability Test, Cronbach's alpha results for the pre-covid were 0.8292 for the pre-COVID-19 questions and 0.8603 for the during COVID-19 question, which means that the questions have a good internal consistency. In short, the questions are not confusing to the respondents.

Data Gathering and Analysis

The researcher used primary data to support the claim of this study, while secondary data are from verified and trusted journals. The participants' list came from the DTI and the Business Process and Licensing Office-Talavera. The researcher approached the respondents with retrieved contact information and asked them to answer the google form. For those challenged with the online questionnaire, the researcher handed over the printed questionnaire to the MSMEs' owner, manager, or representative.

Treatment of Data

The researcher measured the significant difference in retailing decisions of MSMEs for merchandise management and store management based on the length of operation, size, retail format, and legal entity.

The researcher used statistical tools such as measures of central tendency, frequency, and percentage, t-test, and proportion test to analyze the data and ascertain the interpretation of the findings from the data collected. Additionally, some literature, including Cheungsuvadee (2006) and Kakkar (2016), used some of the above-mentioned statistical tools to analyze the data.

Results and Dicussion

This section presents the results and the researcher's discussion to interpret the data gathered for which statistical tools were employed(Table 1).

| Table 1 Respondent’s Profile |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | ||

| Years of Operation | |||

| micro | 149 | 11.15 | |

| small | 21 | 12.62 | |

| medium | 4 | 15.25 | |

| n | Proportion (%) | ||

| Position of Respondents | |||

| manager | 15 | 8.60 | |

| owner | 115 | 66.10 | |

| representative | 44 | 25.30 | |

| Size of Business | |||

| micro | 149 | 85.60 | |

| small | 21 | 12.10 | |

| medium | 4 | 2.30 | |

| Legal form of business | |||

| sole proprietorship | 156 | 89.70 | |

| partnership | 16 | 9.20 | |

| others | 2 | 1.10 | |

| Retail Format | |||

| general merchandise | 61 | 36.30 | |

| grocery story | 57 | 33.90 | |

| others | 50 | 29.80 | |

For years of operation, the researcher considered the business operating for more than five years stable. As stated, time is a concept long associated with the notion of stability (Halinen & Tornroos,1995). Findings revealed that, on average, the 174 respondents have been in operation for eleven years, micro-enterprises for 11 years, small enterprises for 12 years, and medium enterprises for 15 years with 66.10% who are the owners of the businesses, followed by the representatives and managers.

The majority of the respondents' businesses are micro-enterprises. This was followed by 12% of small and 2% of medium enterprises. The finding is in support of the Department of Trade and Industry (2020), which claims that microenterprises account for 88.77% of total MSME establishments, with small businesses accounting for 10.25% and larger businesses accounting for 49%. In enterprise's legal entity, sole proprietorships are greatest in number, followed by 9.20% of partnership classification and 1.10% for corporations. The majority of the respondents are in general merchandise classification.

Table 2 shows that before the pandemic conducting market research is prevalent, with 62.60% of respondents using it as a forecasting technique. During the pandemic, the comparison of past sales got the highest percentage, with 52.90%. In terms of the types of inventory carried by the business, finished inventory got the highest percentage with 64.40% before 55.20% during the pandemic. In the inventory management techniques implemented, first in and first out (FIFO) got the highest percentage, with 62.60% before and 54.60% during the pandemic. In using software or technology, the majority of the respondents do not use software or technology before 69% and 71.80% during the pandemic. In the mode of receiving at the store, the delivery of purchased orders are prevalent with 68.40% before and 64.40% during the pandemic. In purchase decisions, buying decisions are usually managed in the store with 74.70% before and 66.10% during the pandemic. In the type of merchandise sold in the store, national brands got the highest percentage, with 80.50% before and 62.10% during the pandemic. For the types of buying situations (supplier of merchandise), straight rebuy (we buy from a regular outside supplier) got the highest percentage with 66.70% before and 63.20% during the pandemic. In setting prices, the majority of the respondents used cost-based pricing before the pandemic with 52.30% and during the pandemic with 49.40%. In terms of setting pricing objectives, 46% of the respondents set maximizing profit as the pricing objective before the pandemic, whereas 52.30% of respondents set increasing sales as the pricing during the pandemic. In the mode of payment, cash payment got the highest percentage both before the pandemic with 82.20% and during the pandemic with 73%. Lastly, for the mode of delivery, the majority of the respondents do not deliver their merchandise in both scenarios.

| Table 2 Merchandise Management Strategies Implemented |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Pre-COVID 19 | During COVID 19 | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| 1. Forecasting Technique used by the business. | ||||

| a. We ask our customers. | 105 | 62.60 | 71 | 42.50 |

| b. We compare our past and present sales. | 74 | 44.30 | 89 | 52.90 |

| c. We seek advice from experts | 42 | 24.70 | 66 | 39.10 |

| d. Others, please specify: ___________ | 8 | 4.60 | 6 | 3.40 |

| e. We did not use forecasting technique. | 26 | 15.50 | 21 | 12.60 |

| 2.Types of inventory carried by the business. | ||||

| a.Raw materials/components inventory | 34 | 20.10 | 16 | 9.80 |

| b.Work-in-progress inventory | 45 | 27.00 | 45 | 27.00 |

| c.Finished goods inventory | 108 | 64.40 | 93 | 55.20 |

| d.Maintenance, repair, and operations inventory | 36 | 21.30 | 37 | 21.80 |

| e.Others, please specify: _______________ | 3 | 1.70 | 1 | 0.60 |

| 3.Inventory management techniques implemented. | ||||

| a.We sell first the merchandise that comes first | 105 | 62.60 | 92 | 54.60 |

| b.We sell first the merchandise that expires first | 62 | 36.80 | 63 | 37.40 |

| c.We receive merchandise only when needed | 43 | 25.90 | 53 | 31.60 |

| d. We order merchandise based on expected demand to prevent stockouts | 76 | 45.40 | 84 | 50.00 |

| e. We group merchandise based on similar traits | 49 | 29.30 | 50 | 29.90 |

| f. Others, please specify: _______________ | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| g.We did not implement inventory management techniques. | 14 | 8.60 | 18 | 10.90 |

| 4.Use of software/ technologies in inventory management. | ||||

| a. We use software for assorting inventories | 16 | 9.80 | 19 | 11.50 |

| b. We use software to categorize inventories | 19 | 11.50 | 17 | 10.30 |

| c. Other, please specify: __________________ | 12 | 6.90 | 9 | 5.20 |

| d. We did not use software for inventory management | 116 | 69.00 | 121 | 71.80 |

| 5.Mode of receiving delivery of purchased orders. | ||||

| a. We receive the merchandise in our stores. | 115 | 68.40 | 108 | 64.40 |

| b. We pick the merchandise from supplier’s warehouse. | 74 | 44.30 | 45 | 27.00 |

| 6. Type of purchase decisions. | ||||

| a. Buying decisions are managed within the store. | 126 | 74.70 | 111 | 66.10 |

| b. Buying decisions come from the head office. | 23 | 13.80 | 12 | 6.90 |

| c. Others, please specify: ____________ | 4 | 2.30 | 5 | 2.90 |

| 7. Type of merchandise sold in the store. | ||||

| a. We purchase goods from manufacturers and sell them as is. | 135 | 80.50 | 104 | 62.10 |

| b. We make the goods we offer for sale. | 35 | 20.70 | 29 | 17.20 |

| c.We use our stores’ name as label for the goods we sell. | 28 | 16.70 | 17 | 10.30 |

| d. We use the name of the goods delivered by the suppliers. | 30 | 17.80 | 24 | 14.40 |

| e. Others, please specify: ____________ | 1 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.60 |

| 8. Supplier of merchandise being sold. | ||||

| a. We have our company-owned supplier. | 37 | 21.80 | 19 | 11.50 |

| b. We buy from outside new supplier. | 47 | 28.20 | 78 | 46.60 |

| c. We buy from outside regular supplier. | 112 | 66.70 | 106 | 63.20 |

| d. Others, please specify. | 4 | 2.30 | 5 | 2.90 |

| 9. Pricing strategies. | ||||

| a. We offer sales discount promotions. | 42 | 25.30 | 38 | 22.40 |

| b. We price our products low. | 59 | 35.10 | 54 | 32.20 |

| c. We price our products high. | 18 | 10.90 | 20 | 12.10 |

| d. We price the products based on cost. | 88 | 52.30 | 83 | 49.40 |

| e. Others, please specify:_____________ | 1 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.60 |

| 10. Pricing Objectives | ||||

| a. To increase sales | 69 | 40.80 | 88 | 52.30 |

| b. To maximize profit | 77 | 46.00 | 56 | 33.30 |

| c. To match competitor’s price | 51 | 30.50 | 45 | 27.00 |

| d. Others, please specify:___________________ | 3 | 1.70 | 2 | 1.10 |

| 11. Mode of payment | ||||

| a. Electronic banking | 10 | 5.70 | 14 | 8.60 |

| b. Online wallet | 21 | 12.60 | 53 | 31.60 |

| c. Cash payment | 138 | 82.20 | 123 | 73.00 |

| d. Check payment | 13 | 7.50 | 18 | 10.90 |

| e. Others, please specify: _______________ | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.60 |

| 12. Mode of delivery for sold merchandise | ||||

| a. We have our own rider. | 45 | 27.00 | 33 | 19.50 |

| b. We have an external partner for delivery. | 23 | 13.80 | 14 | 8.60 |

| c. We do not deliver sold merchandise. | 87 | 51.70 | 77 | 46.00 |

| d. Others, please specify: _________ | 4 | 2.30 | 3 | 1.70 |

Findings revealed that generally speaking, there is no significant difference in the implemented merchandise management strategies since the P value is 0.1753. However, below are the specific significant factors in terms the merchandise management(Table 3):

| Table 3 Significant Factors In Merchandise Management Techniques Implemented |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Merchandise Management Techniques | Test statistic | p-value | |

| Forecasting Technique used by the business. | Proportion test | ||

| We ask our customers. | 3.7574 | 0.0002 | |

| We seek advice from experts | -2.8754 | 0.004 | |

| Types of inventory carried (held) by the business. | |||

| Raw materials/components inventory | 2.7065 | 0.0068 | |

| Mode of receiving delivery of purchased orders. | |||

| We pick the merchandise from supplier’s warehouse. | 3.358 | 0.0008 | |

| Type of purchase decisions. | |||

| Buying decisions come from the head office. | 2.1122 | 0.0347 | |

| Type of merchandise sold in the store. | |||

| We purchase goods from manufacturers and sell them as is. | 3.7907 | 0.0002 | |

| Supplier of merchandise being sold. | |||

| We have our company-owned supplier. | 2.5891 | 0.0096 | |

| We buy from outside new supplier. | -3.546 | 0.0004 | |

| Pricing Objectives | |||

| To increase sales | -2.1493 | 0.0316 | |

| To maximize profit | 2.4108 | 0.0159 | |

| Mode of payment | |||

| Online wallet | -4.2616 | 0.0000 | |

| Cash Payment | 2.0567 | 0.0397 | |

This study found that the significant factors that made a difference in merchandise management in pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 are forecasting, types of inventory carried, mode of receiving merchandise, buying decisions, merchandise sold, buying situation, and mode of payment. In the forecasting technique, startups face a dearth of market and marketing research (Salamzadeh & Kesim, 2017). MSMEs seek more advice from the experts (delphi method) when the pandemic hit the country. The types of inventory carried by the business change from most (20.10%)of the respondents carrying raw materials to having least (9.80%) of respondents not carrying raw material. The mode of receiving merchandise changes from most (44.30%) of the respondents picking up the merchandise to least (27%) of the respondents picking up the goods from their supplier. This is because of the imposed restrictions on the borders, especially when the whole country is under the Enhanced Community Quarantine (Official gazette of the Philippines, 2020), in which, as time goes by, the government eases the regulations for retailing activities. With this situation, Sands & Ferraro (2010) corroborate that supplier collaboration emerged aided by online transactions. The types of purchase decisions change from most (13.80%) of the respondents' decisions at the central level to least (6.90%) depending on the central level. Hence, store personnel play a significant role. The types of merchandise sold change from most (80.50%) of the respondents having to sell the national brands to least (62.10%) of the respondents having to sell national brands. This can be seen in the growth of private label brands and generic brands. Vimari (2018) corroborates that private label brands grew four times faster than national brands. For the buying situations (supplier of merchandise), there is a shift from having a company-owned supplier to looking for a new one. From practicing straight rebuy, the respondents now welcome the idea of modified rebuy, where the buyer requests alterations to the product's details, price, delivery requirements, or other terms. In pricing objectives, the respondents now focus on increasing sales due to sales decrease during the pandemic (Bartik et al., 2020). Lastly, among the factors enumerated, the mode of payment has changed significantly, whereby MSMEs are practicing the use of online wallets during the pandemic compared to before (Yang et al., 2021). Notably, although cash payments are still and will never be replaced, at least in the succeeding years to come, findings revealed that the use of cash payments reduces during the impact of the pandemic. Cash payments result in more significant price reductions than non-cash payments. Contrary to this, Xu et al. (2020) argue that cash payments resulted in a higher selling price under some scenarios than e-payments despite that some companies still lack technological readiness (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020).

Table 4 shows how the MSMEs perceived the importance of merchandise management strategies. In planning for merchandise to sell, MSMEs perceived the customer to serve as the most important consideration with a mean of 4.69 before and 4.71 during the pandemic. In terms of maintaining the quality of merchandise, customer to serve is the number one consideration, with 4.74 mean before and 4.76 mean during the pandemic. When selecting a supplier, the vital consideration for MSMEs is the price of the merchandise with 4.65 mean before and 4.66 mean during the pandemic. In allocation and replenishment, the relationship with their customers is vital with 4.30 before the pandemic and changed to capital accessibility with a mean of 4.65 during the pandemic. Lastly, the use of software to aid in sorting was viewed as most important before the pandemic with 1.87 mean, while during the pandemic, MSMEs viewed software helps in the coordination of data needed in management with 2.60 mean.

| Table 4 Perceived Importance Of Merchandise Management Strategies |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | PRE COVID-19 | DURING COVID-19 |

| Mean | Mean | |

| 1. Planning for merchandise (inventory/goods for sale) | 4.29 | 4.55 |

| a. Customers to serve | 4.69 | 4.71 |

| b. Products | 4.60 | 4.60 |

| c. Retailer’s image | 4.49 | 4.58 |

| d. Competition | 3.95 | 4.34 |

| e. Amount of Investment | 4.23 | 4.58 |

| f. Profitability | 4.54 | 4.60 |

| g. Risks | 3.56 | 4.43 |

| 2. Maintaining the quality of merchandise (goods) | 4.11 | 4.25 |

| a. Customers to serve | 4.74 | 4.76 |

| b. Competition | 4.30 | 4.34 |

| c. Store location | 4.24 | 4.59 |

| d. Stock turnover (how quick a stock is sold and replaced) | 4.09 | 4.46 |

| e. Profitability | 4.57 | 4.57 |

| f. Manufacturer brands (brand purchased from supplier) | 4.33 | 4.32 |

| g. Private brands (own brand developed by the store) | 3.51 | 3.69 |

| h. Generic brands (No brand) | 3.06 | 3.27 |

| 3. Selecting Supplier | 4.34 | 4.59 |

| a. Price of products the supplier offers | 4.65 | 4.66 |

| b. Quality of products the supplier offers | 4.62 | 4.64 |

| c. Reliability of the supplier | 4.60 | 4.64 |

| d. Order processing time the supplier offers | 3.95 | 4.47 |

| e. How much guarantee a supplier offers | 4.05 | 4.56 |

| f. Payment terms of supplier | 4.15 | 4.59 |

| 4. Allocation and Replenishment | 4.12 | 4.52 |

| a. Management planning | 4.27 | 4.56 |

| b. Employed marketing strategies | 3.87 | 4.27 |

| c. Relationship towards customers | 4.30 | 4.48 |

| d. Business environment | 3.94 | 4.63 |

| e. Capital accessibility | 4.24 | 4.65 |

| 5. Use of Software or Technology in Inventory Management | 1.85 | 2.58 |

| a. Software support merchants in sorting inventory | 1.87 | 2.58 |

| b. Software aid in categorizing inventory | 1.84 | 2.57 |

| c. Software aids systematic preparation for forecasts | 1.83 | 2.55 |

| d. Software helps in coordination of data needed in management engagement | 1.85 | 2.60 |

Based on the P value of 0.0000, this perceived importance of merchandising management strategies has a significant change. Evidently, MSMEs gave more importance to the factors such as planning for merchandise, maintaining the quality of merchandise, selecting suppliers, allocation and replenishment, and use of software or technology in inventory management (Kakkar, 2016) during the COVID 19 since the mean of these factors went up. It is a good sign that the respondents of this research were open to change for the success of their business. Although there is hope that matters will revert to their former methods of doing things and working, there is a profound cynicism that cautions us about the dangers of such a naive optimism and warns us of the impending new normal we might be on our way there (Seetharaman, 2020).

Table 5 shows that generally speaking, this study rejects Hypothesis 1: "There is a significant difference in the strategies between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 in terms of Merchandise Management." This study then concludes that there is no significant difference in the implemented merchandising strategies. However, some factors under the merchandise management strategies have significant changes.

| Table 5. Implemented Merchandise Management And Perceived Importance Of Merchandise Management Strategies T-Test For Precovid vs. During Covid |

|

|---|---|

| Statistical test | T test |

| Implemented merchandise management strategies (preCOVID versus during COVID) | |

| Test statistic | 1.3582 |

| p-value | 0.1753 |

| Perceived importance of merchandise management strategies (preCOVID versus during COVID) | |

| Test statistic | 20.4394 |

| p-value | 0.0000 |

Further, the result suggests that this study accepts the Hypothesis 3:” There is a significant difference in the perceived importance of merchandise management strategies between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19.” The study then concludes that there is a significant change in the perceived importance of merchandise management strategies. Even though there is not enough evidence to say that there is a significant change in the implemented merchandise management strategies, the idea of change and giving importance to managing the merchandise do not cause fear in the MSMEs, which is a good sign. To this, Boraytynska (2016) concluded that companies who cannot make sufficient modifications to market competitive conditions at the appropriate time are ejected from the market(Table 6).

| Table 6 Store Management Strategies Implemented |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Pre-COVID 19 | During COVID 19 | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| 1.Store layout | ||||

| a. We arrange the shelves both side of aisles with cashier at the entrance | 107 | 63.8 | 124 | 73.6 |

| b.We arrange the merchandise per category following the loop formation. Usually we deploy cashier from each category | 42 | 25.3 | 52 | 31.0 |

| c. We do not follow any layout store. We employ asymmetrical pattern | 30 | 17.8 | 24 | 14.4 |

| d. Not applicable | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 2.Catching customer’s attention | ||||

| a. We catch the customers’ attention through window displays | 89 | 52.9 | 90 | 53.4 |

| b. We catch the customers’ attention at the entrance of the store | 85 | 50.6 | 49 | 29.3 |

| c. We catch the customers’ attention through displaying products at the end of an aisle of the stores | 42 | 24.7 | 24 | 14.4 |

| d. We catch the customers’ attention through displaying promos of products | 62 | 36.8 | 65 | 38.5 |

| e. Others, please specify: _______________ | 5 | 2.9 | 3 | 1.7 |

| f. We do not have a store that catches customer attention. | 14 | 8.0 | 13 | 7.5 |

| 3.Organizing Fixtures | ||||

| a. We use long pipe attached to floor or wall to hang the merchandise | 26 | 15.5 | 17 | 10.3 |

| b. We use circle-shaped fixture attached to stand to display the merchandise | 14 | 8.0 | 15 | 9.2 |

| c. We use two crossbars attached to each other to hang the merchandise | 15 | 9.2 | 17 | 10.3 |

| d. We use fixtures with multiple level of shelves to display the merchandise | 106 | 63.2 | 99 | 59.2 |

| e. Other, please specify___________ | 10 | 5.7 | 3 | 1.7 |

| f. We do not organize our fixtures. | 35 | 20.7 | 25 | 14.9 |

| 4.Recruitment of store personnel | ||||

| a. We are hiring at the store | 85 | 50.6 | 35 | 20.7 |

| b. We use online platforms to hire employees | 17 | 10.3 | 11 | 6.3 |

| c. We use the combination of hiring at the store and online | 8 | 4.6 | 14 | 8.0 |

| d. We accept referrals for applicants to the position | 31 | 18.4 | 49 | 29.3 |

| e. Others, please specify: ____________ | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.6 |

| f. We do not hire store personnel. | 49 | 29.3 | 60 | 35.6 |

| 5. Use of promotional tools | ||||

| a. We advertise our business through TV, radio, newspaper, tarpaulin | 24 | 14.4 | 47 | 28.2 |

| b. We advertise our business by offering customers coupons, discounts, etc. | 21 | 12.6 | 29 | 17.2 |

| c. We advertise our business with the help of our employees | 18 | 10.9 | 18 | 10.9 |

| d. We advertise our business by building and maintaining our positive image | 64 | 37.9 | 51 | 30.5 |

| e. Others, please specify: ____________________________ | 5 | 2.9 | 2 | 1.1 |

| f. We do not use promotional tools. | 96 | 56.9 | 64 | 37.9 |

| 6. Use of online presence | ||||

| a.Social Networking sites | 28 | 16.7 | 61 | 36.2 |

| b.Website | 9 | 5.2 | 17 | 10.3 |

| c.Other, please specify___________ | 4 | 2.3 | 6 | 3.4 |

| d.We do not use online presence | 119 | 70.7 | 78 | 46.6 |

| 7. Communicating with actual and potential customers | ||||

| a. We use tarpaulin and other poster | 70 | 42.0 | 39 | 23.0 |

| b. We use signage | 53 | 31.6 | 99 | 59.2 |

| c. We rely to the feedback of customers to their family and friends | 83 | 49.4 | 79 | 47.1 |

| d. Other, please specify___________ | 7 | 4.0 | 7 | 4.0 |

| 8. Delivery of service | ||||

| a.We deliver the service according to customers’ needs | 79 | 47.1 | 74 | 44.3 |

| b. We deliver the service based on the store’s standard | 78 | 46.6 | 83 | 49.4 |

This table shows that grid layout (arrange the shelves on both sides of aisles with the cashier at the entrance) got the highest percentage in both of the situations with 63.8% before and 73.6% during the pandemic. In terms of catching customers' attention (featured areas), catching the customers' attention through window displays got the highest percentage, with 52.9% before and 53.4% during the pandemic. In organizing fixtures, gondolas (use fixtures with multiple levels of shelves to display the merchandise) got the highest percentage with 63.2% before and 59.2% during the pandemic. In terms of recruitment of personnel, hiring at the store gained the highest percentage of 50.6% before the pandemic, while hiring by referrals during the pandemic is prevalent with 29.3%. The majority of the respondents before the pandemic (56.9%) and during the pandemic (37.9%) do not engage themselves in any major promotional activities. This is also the same with the use of online presence with not engaging in online got the highest score but has a significant change. Although most of the respondents still do not engage in such, there are significant increases noted in using promotional and online presence. In terms of communication with the customers, most MSMEs use feedback from the family and friends (49.4%) before the pandemic and signage (59.2%) during the pandemic. Consequently, before the pandemic, MSMEs delivered the services according to the customer's preference with 47.1%, while during the pandemic, it changed to delivering services based on the store's standards with 49.4%.

This study suggests that there is no significant difference in the implemented store management strategy since the P value is 0.2590. The significant factors under the store management strategies are shown in Table 7.

| Table 7 Significant Factors In Store Management Strategies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Store Management Techniques Implemented | Test Statistic | p-value | |

| Store layout | proportion test | ||

| We arrange the shelves both side of aisles with cashier at the entrance | -1.9648 | 0.0494 | |

| Catching customer’s attention | |||

| We catch the customers’ attention at the entrance of the store | 4.0496 | 0.0001 | |

| We catch the customers’ attention through displaying products at the end of an aisle of the stores | 2.4335 | 0.015 | |

| Recruitment of store personnel | |||

| We are hiring at the store | 5.8205 | 0.0000 | |

| We accept referrals for applicants to the position | -2.3899 | 0.0169 | |

| Use of promotional tools | |||

| We advertise our business through TV, radio, newspaper, tarpaulin etc. | -3.1442 | 0.0017 | |

| We do not use promotional tools. | 3.5427 | 0.0004 | |

| Use of online presence | |||

| Social Networking sites | -4.1329 | 0.0000 | |

| We do not use online presence | 4.5713 | 0.0000 | |

| Communicating with actual and potential customers | |||

| a. We use tarpaulin and another poster | 3.7777 | 0.0000 | |

| b. We use signage | -5.168 | 0.0000 | |

This study rejects Hypothesis 2: "There is a significant difference in the strategies between preCOVID and during COVID in terms of Store Management." From hindsight, wherein government restrictions are in place (Schleper et al., 2021), it can be said that the store layout, featured areas, recruitment of store personnel, use of promotional tools, and use of online presence have a significant difference in operations in preCOVID and during COVID19. However, this study says otherwise. There are some factors under the store management strategies that change. For instance, restaurant regulars have moved their preferences to off-premise dining, drive-through food pickup, and ready-to-eat meals due to the lockout (Seetharaman, 2020). Many in-store customers' experiences were based on promoting fun, entertainment, and engagement preCOVID, while during COVID, customers rate their experience depending on how clean it is, if they do not have to touch a screen, and whether the store is large enough to allow social separation (Roggeveen & Sethuraman, 2020) and whether or not there is an online platform where they can order (Toh & Tran, 2020)(Table 8).

| Table 8 Perceived Importance Of Store Management Strategies |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Pre-COVID 19 | During COVID 19 |

| Mean | Mean | |

| 1. Creating an appealing store atmosphere | ||

| a.Lighting | 4.78 | 4.56 |

| b.Color | 3.67 | 4.11 |

| c.Music | 3.33 | 3.67 |

| d.Scent | 3.67 | 3.89 |

| e. Others, please specify: __________ | 3.22 | 3.67 |

| 2. Space Allocation | ||

| a. We compare the total sales of the store from the space of merchandise used per category | 3.64 | 3.88 |

| b. We measure the number of times inventory is sold in a given period of time | 3.69 | 3.95 |

| c. We consider the effect on overall store sales | 4.43 | 4.77 |

| d. We study the space to use in designing the store | 3.99 | 4.43 |

| 3. Use of promotional tools | ||

| a. We advertise our business through TV, radio, newspaper, tarpaulin etc. | 4.05 | 4.17 |

| b. We advertise our business by offering customers coupons, discounts, etc. | 3.75 | 3.81 |

| c. We advertise our business with the help of our employees | 4.13 | 4.27 |

| d. We advertise our business by building and maintaining our positive image | 4.27 | 4.43 |

| e. Other, please specify: ______________ | ||

| 4. Use of signage and graphics to communicate to customers | ||

| a. We use signage to call the attention of customers | 4.12 | 4.58 |

| b. We use signage to categorize the merchandise | 3.71 | 4.22 |

| c. We use signage to describe products promo | 3.70 | 3.82 |

| d. We use signage near the merchandise it refers to display the price or other important information | 3.76 | 4.10 |

| e. We use signage that are posted in electronic platforms | 3.58 | 3.64 |

Table 8 shows that in creating an appealing store atmosphere, lighting was perceived as the most important, with 4.78 mean before and 4.56 mean during the pandemic. In terms of space allocation, most of the MSMEs considered the overall store sales vital, with 4.43 mean before and 4.77 mean during the pandemic. In using promotional tools, MSMEs believed it is important to maintain a positive image, with 4.27 mean before and 4.42 during the pandemic. And lastly, MSMEs perceived signage as a way to catch the customers' attention, with 4.12 mean before and 4.58 mean during the pandemic.

Moreover, the significant factors that made a difference in store management in pre-COVID and during COVID are store layout, catching customers' attention, recruiting store personnel, use of advertisement, use of social media, and communicating with their actual and potential customers. For the store layout, MSMEs put the cashier at the entrance of their store during COVID19. For their safety, most (73.6%) of the respondents entertain their customers in front of their store, while some offers online and deliverable products (Toh & Tran, 2020). In catching customers' attention (featured areas), least (14.4%) of respondents use end caps, where they display products at the end of the store because of government restrictions (Fairlie, 2020). Recruiting of store personnel was interpreted as least (20.7%) of the respondents hired at the store; instead, they are more open to accepting referrals. The use of advertisements is prevalent. Advertising is more of non-personnel promotion; it can be in the form of emails, posters posted on social media, and the like. Respondents are now practicing promotional tools compared to preCOVID. The use of social media is more prevalent during COVID. Lastly, most (59.2%) of the respondents during COVID are communicating with their actual customers and potential customers using digital and print signage. In short, the majority of the transaction are aided by online platforms (Vojvodi?, 2019; Dannenberg et al., 2020)

As computed, the perceived importance of store management strategies has significant change. From a researcher's perspective, it is a good sign since the respondents were open to change for the success of their business. Since today's retail establishments are more than just a place to shop offline, they have grown into a cross-channel interaction hub (Mou et al., 2018)(Table 9).

| Table 9 Implemented Store Management Strategies And Perceived Importance Of Store Management Strategies t-test For Precovid Versus. During covid |

|

|---|---|

| Statistical test | T test |

| Implemented store management strategies (preCOVID versus during COVID) | |

| Test statistic | 1.1307 |

| p-value | 0.2590 |

| Perceived importance of store management techniques (preCOVID versus during COVID) | |

| Test statistic | -4.1631 |

| p-value | 0.0000 |

The table shows that Generally speaking, this study rejects Hypothesis 2: "There is a significant difference in the strategies between pre-Covid and during Covid in terms of Store Management." The result suggests that there is not enough evidence to say that the store management strategies implemented changed due to the pandemic factors.

Furthermore, this study accepts the Hypothesis 4: “There is a significant difference in the perceived importance of store management strategies between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19.” To this, the results suggests that there is a significant change in the perceived importance of store management strategies. Even though there is not enough evidence to say that there is a significant change in the implemented store management strategies, the idea of giving importance to managing the store and the MSMEs are open to changes, which the theory of natural selection emphasizes.

Conclusion

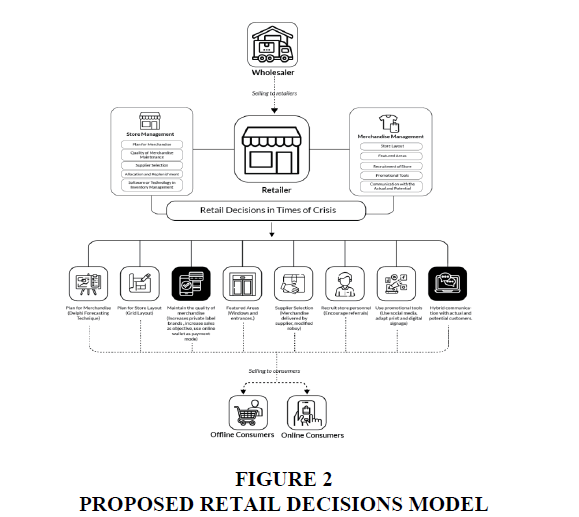

In conclusion, the retailing decisions of MSMEs in terms of merchandise management include planning for merchandise, maintaining the quality of merchandise, selecting suppliers, allocation and replenishment, and use of software or technology in inventory management. Moreover, retailing decisions regarding store management include store layout, featured areas, recruitment of store personnel, promotional tools, and communication with actual and potential customers.

Based on the findings, this study concludes that MSMEs are now shifting from brick-and-mortar to brick-and-click operations at the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, generally speaking, there is not enough evidence to say that the MSMEs implemented retail decisions regarding merchandise management and store management in preCOVID and during COVID- changes. However, among the factors considered in Figure 2, significant factors were noted (please see Table 3 and Table 7 for the summary in tabular form). Nevertheless, the perceived importance of the merchandise and store management strategies was noted.

Futhermore, this study concludes that scant literature on the dynamics of merchandise and store management was noted. However, the method of doing so has changed as technology has supported these decisions. Moreover, MSMEs perceived importance of the merchandise and store management strategies changed significantly, which is a good sign since it indicates that they are open to changes in the business landscape. This led to the finding that merchandise and store management must be intertwined in retail decisions. Hence, this study led to the proposal of the retail decisions model shown in the figure below, which might help contribute to the body of knowledge of marketing.

Recommendations

This study recommends a more comprehensive study regarding the retailing decisions of MSMEs that will cover not only one municipality with top registered MSMEs but at least an entire province must be conducted. It further recommends looking into the use of online in conducting a business. More significantly, the use of social media and online payment since these are one of the significant changes in this study where MSMEs grasp the use of these platforms that are new to them. The do’s and the don’ts in managing the merchandise, for instance, how to effectively use online platforms in conducting market research? What are the contents that should be uploaded to social media? How to aesthetically capture their products to be uploaded to their online store? How to generate barcodes for their online wallet and online store? are some of the topics that can be explored.

It is also recommended that MSMEs must be careful in the conduct of their business especially when transacting online. The government should therefore focus on giving intensive training to MSMEs in terms of how the MSMEs can proficiently use online platforms like online payment and social media to efficiently and effectively decides on the retailing activities to consider.

References

Asia Development Bank. (2021). Asian Development Bank. Asian Development Outlook (ADO).

Bartik, A.W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E.L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(30), 17656–17666.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brooks, B. (2008). The natural selection of organizational and safety culture within a small to medium sized enterprise (SME). Journal of Safety Research, 39(1), 73–85.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cheungsuvadee, K. (2006). Business Adaptation Strategies Used By Small and Medium Retailers in an Increasingly Competitive Environment?: A Study of Ubon Ratchathani,. December.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2019). Micro-, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) and their role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Sustainable Development Goals.

Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117(6), 284–289.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fairlie, R. W. (2020). The impact of covid-19 on small business owners: evidence of early-stage losses from the April 2020 Current Population Survey. NBER Working Paper Series, May, 1–23.

Grewal, D., Motyka, S., & Levy, M. (2018). The Evolution and Future of Retailing and Retailing Education. Journal of Marketing Education, 40(1), 85–93.

Kakkar, N. (2016). Merchandise Management in Retailing: A study of Apparel Specialty Store in Ludhiana. Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana.

Kök, A., Fisher, M., & Vaidyanathan, R. (2008). Assortment planning?: review of literature and industry.

Kök, A., & Fisher, M., (2007). Demand estimation and assortment optimization under substitution: Methodology and application. Operations Research, 55(6), 1001-1021.

Kumar, B., & Banga, G. (2007). Merchandise planning: an indispensable component of retailing. The Icfaian Journal of Management Research, 6(11), 7–19

Levy, M., Weitz, B.A., & Grewal, D. (2014). Retailing Management (Ninth Edit). McGraw-Hill Education. www.mhhe.com

Madaan, K. (2009). Fundamentals of retailing. Journal of Marketing, 5(2).

Mantrala, M., Levy M., Kahn, B., Fox., Gaidare, P., Dankworth, B., & Shah, D. (2009). Why is Assortment Planning so Difficult for Retailers? A Framework and Research Agenda. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 71-83.

Mou, S., Robb, D. J., & DeHoratius, N. (2018). Retail store operations: Literature review and research directions. European Journal of Operational Research, 265(2), 399–422.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pantano, E., Pizzi, G., Scarpi, D., & Dennis, C. (2020). Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Business Research, 116(5), 209–213.

Park, J.H., & Park, S.C. (2003). Agent-based merchandise management in business-to-business electronic commerce. Decision Support Systems, 35(3), 311–333.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roggeveen, A. L., & Sethuraman, R. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic may change the world of retailing. Journal of Retailing, 96(2), 169–171.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Seetharaman, P. (2020). Business models shifts: Impact of Covid-19. International Journal of Information Management, 54(June), 1–4.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Toh, Y. L., & Tran, T. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic may reshape the digital payments landscape. Payments System Research Briefing, 1–10.

Vojvodi?, K. (2019). Brick-and-mortar retailers: Becoming smarter with innovative technologies. Strategic Management, 24(2), 3–11.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yang, M., Al Mamun, A., Mohiuddin, M., Nawi, N.C., & Zainol, N. R. (2021). Cashless transactions: A study on intention and adoption of e-wallets. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(2), 1–18.

Received: 12-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12668; Editor assigned: 14-Oct-2022, PreQC No. AEJ-22-12668(PQ); Reviewed: 22-Oct-2022, QC No. AEJ-22-12668; Revised: 25-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12668(R); Published: 02-Jan-2023