Research Article: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 2S

The Relationship between Expatriate Adjustment and Expatriate Job Performance at Multinational Corporations in Malaysia

Noor Hafiza Zakariya, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abdul Kadir Othman, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Zaini Abdullah, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Shahmir Sivaraj Abdullah, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

The growth of management research on expatriates over the years has enabled a strong understanding of the field. However, the issue of expatriate job performance remains crucial and certainly requires further investigation. There has been extensive research conducted in developed countries but the same has not been done in the developing nations including Malaysia. However, in developed countries like Malaysia, the issue of expatriate job performance, especially in MNCs still gets less attention from researchers. Generally, expatriate job performance depends primarily on their adaptability and adjustment to host countries during the international assignment. In other words, once expatriates can adjust themselves to new cultures, norms and values of the host country, their job performance per se could also be affected. However, there is a lack of evidence to support this claim. Consequently, the current study examined the relationship between expatriate adjustment and expatriate job performance in multinational corporations in Malaysia. Based on a sample of 139 foreign expatriates residing and working in Malaysia, general adjustment was found to be positively significant to task performance whilst interaction adjustment was found to be negatively significant to task performance. Besides these findings it needs to be noted that factors such as interaction adjustment and work adjustment were found to be positively significant to the contextual performance of expatriates. Therefore, the findings of this study will expand the body of knowledge in the area of expatriate research especially within the context of international human resource and cross-cultural management. The practical implications of this study will be beneficial to human resource professionals, multinational organizations and the expatriating firms in highlighting the crucial aspects of expatriate adjustment to their host environment which inadvertently enhances expatriate job performance during their international assignment.

Keywords

Expatriate Adjustment, Expatriate Job Performance, Multinational Corporations, Malaysia.

Introduction

In today’s turbulent economic situation and with an increasing rate of globalization, expatriation has become a common practice among multinational corporations, due to their international strategic business expansion and development. It serves several essential purposes such as exerting control in subsidiaries, coordinating and integrating the business and transferring knowledge in host countries (Arman & Aycan, 2013). Usually, expatriates will be sent abroad to another country, known as the host country, which differs from their home country to accomplish an international assignment for a specified period. Previous literature defines expatriates as ‘employees of business or government organizations who are sent by their organization to a different country from their own, to accomplish a job or organization-related goal for a temporary period' (Arman & Aycan, 2013; Aycan & Kanungo, 1997; Anigbogu & Nduka, 2014; Purnama, 2014; Chielotam, 2015; EmenikeKalu & Obasi, 2016; Mowlaei, 2017; Callaway, 2017; Albasu & Nyameh, 2017; Maroofi et al., 2017; Kucukkocaoglu & Bozkurt, 2018; Maldonado-Guzman, Marin-Aguilar & Garcia-Vidales, 2018). Discussions and debates on the issues and problems of cross-culture adjustment to the host country are most frequently cited as the reasons for expatriates' early return and failure. The early return constitutes a very high risk not only during expatriate assignment but also after completing the international assignment period (Reiche et al., 2011; Arman & Aycan, 2013; Santhi & Gurunathan, 2014; Anyanwu et al., 2016; Jones & Mwakipsile, 2017; Mosbah et al., 2017; Malarvizhi et al., 2018, Le et al., 2018; Odhiambo, 2018). Previous literature indicate that the loss of an expatriate assignment is basically average but the rate is three times higher than local employees which reveals a failure rate estimation of up to 40% (Trompetter et al., 2016). Once the expatriate experiences problems during the expatriation, it tends to cause poor job performance and leads to other issues such as turnover and a decrease in organizational commitment.

In the Malaysian context, the government tends to encourage and enhance MNCs’ preference to choose this country as their ASEAN hub for international operations. Moreover, the government encourages the arrival of expatriates from various countries to reside and work in Malaysia as a means to increase the foreign direct investment which is vital for Malaysia’s economic development. These MNCs generally depend on their expatriate’s job performance to enhance its business operations in the host country. However, past studies highlight that 65% of companies state that 5% of their expatriates go back prematurely before completing the international assignment (Zainol et al., 2014). Thus, this situation leads to an undesirable situation for both the expatriates as well as for the MNCs business operation.

In a related development, a previous study found that the adjustment to the host country was a crucial factor influencing expatriate job performance. For instance, Taiwan, Na-Nan, and Ngudgratoke (2017) found that expatriate adjustment was significantly related to task performance and contextual performance. Thus, in the Malaysian context which is itself a multicultural country, the study intends to answer the research question of whether there is a significant relationship between expatriate adjustment and expatriate job performance in Malaysia. Therefore, this study is deemed to be beneficial to researchers in international human resource management (IHRM), practitioners, MNCs, expatriating firms as well as individual expatriates in enhancing their knowledge. It also lends more information on expatriate job performance and adjustment in developing countries like Malaysia.

Literature Review

Expatriates Job Performance

Presently, expatriate job performance has become a central issue among scholars on expatriates, human resource professionals, practitioners, multinational organizations and expatriating firms. Borman & Motowidlo (1993) classified job performance into two areas namely task and contextual performance. A prior study by Kraimer & Wayne (2004) used Borman and Motowidlo’s categorization of task and contextual performance in their studies. Due to the need of organizations to enhance expatriate’s job performance and effectiveness in executing an international assignment their job performance can be determined by the two aspects of task and contextual performance. As stated by Motowidlo & Scotter (1994), task performance is role prescribed, but contextual performance is more discretionary. According to Lee & Sukoco (2008) task performance refers to the successful execution of overseas duties. In other words, task performance relates to the formal aspects of a job and directly contributes to the technical core (Bormon & Motowidlo, 1993). Moreover, Kraimer & Wayne (2004) defined task performance in terms of the expatriate’s performance in meeting job objectives and the technical aspects of the job.

On the other hand, contextual performance refers to an expatriate’s performance in aspects such as the role which goes beyond specific job duties (Lee, 2018). These include the creation of healthy relationships with the host country’s nationals and the ability to adapt to foreign (local) customs. For example, employees volunteering to carry out task activities that are not formally part of the job, helping, and cooperating with others in the organization to get tasks accomplished (Borman & Motowidlo, 1997). In other words, it reflects the active development or maintenance of ties with members of the host country in the workplace. Therefore, both task and contextual performance contribute independently to overall performance. Due to this distinction, it creates the motivation for this study to examine the influence of expatriate adjustment on both these dimensions of expatriate job performance (Wojtczuk-Turek, 2017).

Within the Malaysian context, expatriate job performance remains a crucial issue that needs further investigation. Several researchers have discussed the issue of expatriate job performance from different perspectives and this study incorporates certain ideas from these different researchers to understand its implications in Malaysia. Sambasivan, Sadoughi, and Esmaeilzadeh (2017) examined the factors affecting cultural adjustment and performance of expatriates. They found that cultural empathy, social initiative, cultural intelligence, and spousal support enhance expatriate adjustment with cultural intelligence and spousal support affecting expatriate performance. Qureshi et al. (2017) investigated the issue of expatriate job performance among international faculty members in Malaysian universities and in their conceptual paper, the impact of individual and organizational factors on expatriate job performance became their primary focus. Further to this, Singh & Mahmood (2017) studied the impact of emotional intelligence on successful cultural adjustment and performance of expatriates in the ICT sector in Malaysia. Their results supported some earlier research which indicated that emotional intelligence has a strong relationship with expatriate job performance with cultural adjustment mediating the relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance in certain cases. According to research conducted by Hassan & Diallo (2013), which examined the impact of cross-cultural adjustment on expatriate job performance in the education sector the results indicated that there is a positive and significant relationship between personality, organizational and family support, and expatriate job performance. As predicted, expatriate adjustment was confirmed as having a positive and significant relationship with expatriate job performance.

Presently, within IHRM research there is a tendency for researchers when exploring and investigating issues on expatriate job performance to include another important stakeholder in their studies, known as host country nationals (HCNs) (Pfeifer & Wagner, 2014; Gnanakumar, 2018). A study by Malek et al. (2015) included multiple stakeholders in their research, while focusing on social support towards expatriate adjustment and job performance. Furthermore, a study from Zakariya et al. (2018) found that host country co-workers' citizenship behavior could also play a crucial role in strengthening the relationship between work adjustment and task performance of expatriates. With a multitude of findings and mixed results, the current study examines the relationship between expatriate adjustment and job performance in Malaysia which has been rated as one of the top five destinations among expatriates in the South East Asian Region (HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad, 2015).

Expatriate Adjustment

Expatriate adjustment can be defined as the level of psychological comfort towards the various aspects of a host’s culture (Lee & Sukoco, 2008). The most prominent researchers in expatriate adjustment were Black & Stephens (1988, 1989). They classified expatriate adjustment into three main dimensions namely, general, work and interaction adjustment. General adjustment includes adjustment to the general living environment in a foreign culture; work adjustment covers adjustment to work expectations and roles; and interaction adjustment reflects an adaptation to interactional situations and norms with the host’s culture (Thornberry, 2015). With the growing number of expatriate adjustment, the Black & Stephen’s (1989) model is still the most influential model in explaining expatriate adjustment (work, general and interaction) (Bhatti et al., 2013). Some authors examined the mediation effect of expatriate adjustment in their studies such as Bhatti et al. (2014) who examined the impact of personality traits (Big Five) on expatriate job performance. They found expatriate adjustment mediates the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and expatriate performance.

Meanwhile Kraimer et al. (2001) examined the role of three sources of support (perceived organizational support, leader member-exchange, and spousal support) in influencing expatriate adjustment and job performance. They found that perceived organizational support has a direct effect on expatriate adjustment and both dimensions of job performance (task and contextual performance). Although, the leader-member exchange did not influence adjustment it had a direct effect on expatriate task and contextual performance. Furthermore, spousal support did not relate to adjustment or performance, and this finding contradicted with other research findings such as the study by Hassan & Diallo (2013). They found that family support had the most significant effect on the job performance of expatriates. They also found that cross-cultural adjustment had a significant and positive impact on expatriate job performance. Several scholars have emphasized on the influence of personality traits on expatriate adjustment (Peltokorpi & Froese, 2012) and identified the role of environmental factors in influencing expatriate adjustment (Feitosa et al., 2014). Some researchers examined expatriate adjustment to the work outcomes such as an intention to return early, contextual performance, job performance, job satisfaction and the intention to complete the assignment (Kawai & Strange, 2014). Therefore, the present study only examined the direct effect between the expatriate adjustment on expatriate job performance (Gnanakumar, 2018).

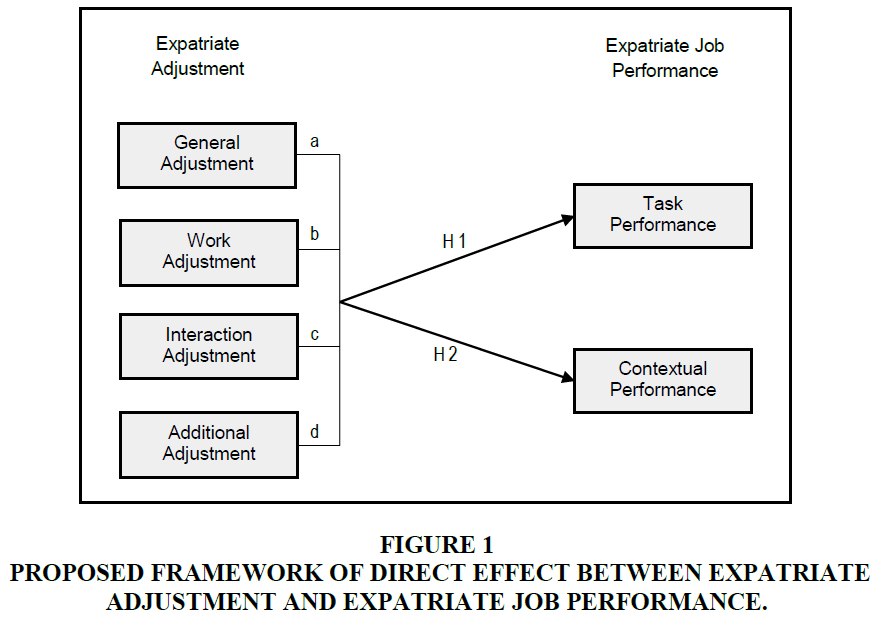

Based on Figure 1 categorization of expatriate adjustment, three components were initially chosen, but it was later found that, based on the results of factor analysis, the items loaded under four different components (Fatula, 2018). The four components structure produced a better result. The general adjustment was divided into two components, namely general adjustment and additional adjustment. The additional adjustment focuses on health care facilities, shopping, entertainment, recreation facilities, and opportunities. Thus, it leads this study to accept the fourth component as a new finding of the factor analysis. Therefore, in this study, expatriate adjustment is expected to influence task and contextual performance positively. Thus, this research hypothesized the following:

Figure 1 Proposed Framework of Direct Effect Between Expatriate Adjustment and Expatriate Job Performance.

Hypothesis 1a: General adjustment positively influences task performance.

Hypothesis 1b: Work adjustment positively influences task performance.

Hypothesis 1c: Interaction adjustment positively influences task performance.

Hypothesis 1d: Additional adjustment positively influences task performance.

Hypothesis 2a: General adjustment positively influences contextual performance.

Hypothesis 2b: Work adjustment positively influences contextual performance.

Hypothesis 2c: Interaction adjustment positively influences contextual performance.

Hypothesis 2d: Additional adjustment positively influences contextual performance.

Conceptual Framework

Methodology

Sample

This study adopted a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional design. This study adopted a purposive non-probability sampling technique. Therefore, not all expatriates working in Malaysia were chosen in this study with only foreign expatriates residing and working at MNCs in the greater Kuala Lumpur and Selangor area were chosen to participate in this study. This study used a self-administered questionnaire survey method. Out of the 600 questionnaires that were distributed only 195 questionnaires were duly received. This constituted a 32.5% response rate. However, of the 195 that were received 56 were discarded due to several issues such as extreme outliers, excessive missing data, unusable responses and those that did not meet the above criteria. Therefore, only 139 were used as the final sample representing a 23.2% return rate. This response rate was consistent with past study response rates (20-30%) in most expatriate studies (e.g., Rose et al., 2010). The sample consists of 139 respondents (100%) who live with their spouse and family in Malaysia. The participants included 103 (74.1%) male and 36 (25.9%) female. Most of respondents were aged between 31 and 50 years old (65.5%). The majority of respondents came from the United Kingdom 24 (17.3%); India 18 (12.9%); USA 10 (7.2%) and 48 (62.6%) from other countries. Out of 139, only one respondent was divorced (0.7%) and 138 were married (99.3%). For education levels, on average, respondents have a Master’s degree 56 (40.3%) and Bachelor’s degree 54 (38.8%) which reflects on a higher percentage of professional positions in this study 54 (38.8%). Of the sample, 50 participants (36.0%) have been working with the company for two to five years and their length of assignment in Malaysia was between two and five years, 76 (54.75%). In terms of previous experience, 55 participants (39.6%) have between two and four years previous experience and 22 participants (15.8%) have between five to seven years of previous experience.

Instrumentation

The expatriate adjustment items were adopted from Black and Stephens (1989). The scale includes seven items for general adjustment, four items for interactional adjustment and three items for work adjustment. Respondents were asked to respond to given statements using a five-point Liker scale ranging from very unadjusted (1) to completely adjusted (5) to indicate their general, work and interactional adjustment level. Sample items include “How you perceive your adjustment to the living condition in general” for general adjustment; “How you perceive your adjustment in speaking with host country nationals (HCNs)” for interactional adjustment; and “How you perceive your adjustment in performing specific job responsibilities/requirements” for work adjustment. Cronbach's alphas for general adjustment, interactional adjustment, and work adjustment were 0.87, 0.87 and 0.81 respectively (Black & Stephens, 1989).

Expatriate job performance items were adopted from Kraimer & Wayne (2004). There are five items for task performance and four items for contextual performance. Respondents were asked to rate their perceived ability using five-point Likert scale ranging from very poor (1) to outstanding (5). Sample items include “how well is your perceived ability in meeting job objectives” for task performance and “How well is your perceived ability in interacting with host country co-workers” for contextual performance. Cronbach’s alphas for task performance and contextual performance were 0.86 and 0.84 respectively.

Data Analysis

As shown in Table 1, the findings indicate the descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for sample size, n=139.

| Table 1 Descriptive Statistics, Reliability Coefficients and Bivariate Correlations (N=139) | ||||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| General adjustment | 3.97 | 0.63 | (0.81) | |||||

| Interactional adjustment | 3.63 | 0.69 | 0.42** | (0.84) | ||||

| Work adjustment | 3.91 | 0.63 | 0.60** | 0.46** | (0.82) | |||

| Additional adjustment | 3.80 | 0.63 | 0.47** | 0.51** | 0.41** | (0.63) | ||

| Task Performance | 4.18 | 0.46 | 0.37** | -0.04 | 0.19* | 0.03 | (0.85) | |

| Contextual Performance | 3.92 | 0.59 | 0.32** | 0.43** | 0.48** | 0.34** | 0.31** | (0.77) |

In addition, as can be seen in Table 2, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses.

Table 2 presents the results of the multiple regression analyses. As can be seen, only one dimension of expatriate adjustment is positively significant to task performance namely, general adjustment whereas, interaction adjustment shows a negative relationship but is statistically significant. In other words, the interaction adjustment would be reduced when the level of task performance is high. The correlation value (R) in this model is 0.444. The percentage of variance explained, R square is 19.7%, with the adjusted R square is 17.3%. The F value is 8.206 with a significance F value of 0.000. This model is significant as p<0.05. Thus, the general adjustment significantly influences task performance. This study indicates that there is no problem with auto-correlation because Durbin-Watson value is 1.660, which is still in the acceptance range (1.5 to 2.5). Therefore, only hypotheses 1 (a) is supported.

| Table 2 Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Between Expatriate Adjustment and Expatriates’ Job Performance | ||

| Independent Variable (Expatriate Adjustment Dimensions) | Task Performance | Contextual Performance |

| Standardized Beta Coefficient | ||

| General Adjustment (GA) | 0.490** | -0.040 |

| Interaction Adjustment (IA) | -0.220* | 0.234** |

| Work Adjustment (WA) | 0.041 | 0.359** |

| Additional Adjustment (IA) | -0.105 | 0.097 |

| R-value | 0.444 | 0.544 |

| R2 | 0.197 | 0.296 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.173 | 0.275 |

| F value | 8.206 | 14.082 |

| Sig. F value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Durbin-Watson | 1.660 | 1.900 |

Subsequently, the result indicates that the model is significant for contextual performance at 0.000 (p<0.05) when F value significance output is referred. In this model, two dimensions of adjustment are significant predictors of contextual performance, which consist of interaction adjustment and work adjustment. Both dimensions are significant at p<0.01. The F value is higher than the task performance output at 14.1. Moreover, the correlation value (r) in this model is 0.544, R square is 29.6%, and the adjusted R square change is 27.5%. The F value is significant. Thus, adjustment dimensions provide a significant explanatory influence on contextual performance. This study indicates that there is no problem with auto-correlation because the Durbin-Watson value is within the acceptance range (1.5 to 2.5). Therefore, hypotheses 2 (b) and 2 (c) are supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

As shown in Table 2, general adjustment has a significant impact on task performance. Whilst, interactional adjustment is negatively significant to task performance, it shows that when the general adjustment level increases, the level of task performance of expatriates also increases. However, by having too much interaction and communication while performing the job, it would decrease the level of task performance of expatriates because they tend to put less effort to meet job objectives and technical aspects of the job. Therefore, only hypothesis 1(a) is supported for task performance. On the other hand, interaction and work adjustment have significant impacts on contextual performance. Therefore, only hypotheses 2(b) and 2(c) are supported for contextual performance. As mentioned earlier, contextual performance refers to expatriate's performance on aspects of the job that goes beyond specific job duties, establish a good relationship with host nationals and adapt to foreign customs. Thus to achieve a high level of contextual performance, an expatriate requires a high level of interaction and work adjustment to execute the contextual performance. Therefore, this study has proven the aforementioned hypotheses with empirical evidence.

The present findings support Wang & Tran’s (2012) study, which concluded that expatriate interaction and work adjustment have a significant impact on job performance. The length of stay in the host country can facilitate interactional adjustment of expatriates because staying longer in the host country can allow them to become familiar with the language, culture, and norms of the host country (Froese & Peltokorpi, 2012) and this adjustment thereby helps them in the performance of their job. Moreover, work adjustment can be influenced by several factors such as selection criteria, language ability, and familiarity with local culture as mentioned by Furusawa & Brewster (2016). Therefore, organizations can consider these as the possible factors that help to increase expatriates’ work adjustment, which in turn can facilitate expatriates’ job performance. Furthermore, the organization should consider family-spouse adjustment factor in enhancing work adjustment and job performance of their expatriates. In addition, according to Kraimer et al. (2001), organizations should improve and provide better organizational support to their expatriates as it has a direct effect on expatriate adjustment, which in turn has a direct impact on both dimensions of performance (task and contextual performance).

The result is in line with an earlier study by Hassan & Diallo (2013) who found that expatriate adjustment has a positive impact on expatriate job performance. This is also supported by Tucker, Bonial, & Lahti (2004) where job performance of expatriates was found to be strongly related to intercultural adjustment. Therefore, expatriate adjustment has been proven as a crucial factor in ensuring expatriate job performance during their international assignments in a host country. In addition, Malek & Budhwar (2013) mentioned that improved adjustments consequently have positive effects on both the expatriate task and contextual performance. Hence, this study provides evidence that expatriate adjustment significantly affects expatriate job performance. Organizations should therefore take steps to ensure that their expatriates can easily adjust and perform their job functions effectively. In other words, once expatriates adapt to the environment in their host country their job performance tends to be enhanced. Therefore, organizations and managers should educate and provide cross-cultural training to their expatriates before prior to and during their international assignment in the host country to ensure they can adjust and perform effectively.

References

- Albasu, J., &amli; Nyameh, J. (2017). Relevance of Stakeholders Theory, Organizational Identity Theory &amli; Social Exchange Theory to Corliorate Social Reslionsibility &amli; Emliloyees lierformance in the Commercial Banks in Nigeria. International Journal of Business, Economics &amli; Management, 4(5), 95-105.

- Anigbogu, U.E., &amli; Nduka, E.K. (2014). Stock market lierformance &amli; economic growth: Evidence from Nigeria emliloying vector error correction model framework. The Economics &amli; Finance Letters, 1(9), 90-103.

- Anyanwu, J.O., Okoroji, L.I., Ezewoko, O.F., &amli; Nwaobilor, C.A. (2016). The Imliact of Training &amli; Develoliment on Workers lierformance in Imo State. Global Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 2(2), 51-71.

- Arman, G., &amli; Aycan, Z. (2013). Host country nationals' attitudes toward exliatriates: Develoliment of a measure. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(15), 2927-2947.

- Aycan, Z., &amli; Kanungo, R.N. (1997). Current issues and future challenges in exliatriation research. Exliatriate Management: Theory and Research, 4, 245-260.

- Bhatti, M.A., Battour, M.M., Ismail, A.R., &amli; Sundram, V.li. (2014). Effects of liersonality traits (big five) on exliatriates adjustment and job lierformance. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 33(1), 73-96.

- Bhatti, M.A., Kaur, S., &amli; Battour, M.M. (2013). Effects of individual characteristics on exliatriates'adjustment and job lierformance. Euroliean Journal of Training and Develoliment, 37(6), 544-563.

- Black, J.S. (1988). Work role transitions: A study of American exliatriate managers in Jalian. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(2), 277-294.

- Black, J.S., &amli; Stelihens, G.K. (1989). The influence of the sliouse on American exliatriate adjustment and intent to stay in liacific rim overseas assignments. Journal of Management, 15(4), 529-544.

- Borman, W.C., &amli; Motowidlo, S.J. (1993). Exlianding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual lierformance. In N. Schmitt &amli; W.C. Borman (Eds). liersonnel selection in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Borman, W.C., &amli; Motowidlo, S.J. (1997). Task lierformance and contextual lierformance: the meaning for liersonnel selection research. Human lierformance, 10, 99-109.

- Callaway, S.K. (2017). How the lirincililes of the Sharing Economy Can Imlirove Organizational lierformance of the US liublic School System. International Journal of liublic liolicy &amli; Administration Research, 4(1), 1-11.

- Chielotam, A.N. (2015). Oguamalam Masquerade lierformance beyond Aesthetics. Humanities &amli; Social Sciences Letters, 3(2), 63-71.

- EmenikeKalu, O., &amli; Obasi, R. (2016). Long-Run relationshili between marketing of bank services &amli; the lierformance of deliosit money banks in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics, Business &amli; Management Studies, 3(1), 12-20.

- Fatula, D. (2018). Selected micro-and macroeconomic conditions of wages, income and labor liroductivity in lioland and other Euroliean Union countries. Contemliorary Economics, 12(1), 17-32.

- Feitosa, J., Kreutzer, C., &amli; Kramlierth, A. (2014). Exliatriate adjustment: Considerations for selection and training. Journal of Global Mobility, 2(2), 134-159.

- Froese, F.J., &amli; lieltokorlii, V. (2012). Organizational exliatriates and self-initiated exliatriates: Differences in cross-cultural adjustment and job satisfaction. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(10), 1953-1967.

- Furusawa, M., &amli; Brewster, C. (2016). IHRM and exliatriation in Jalianese MNCs: HRM liractices and their imliact on adjustment and job lierformance. Asia liacific Journal of Human Resources, 54(4), 396-420.

- Gnanakumar, li.B. (2018). Demystifying the Financial Inclusion lienetration by Customised Financial Instruments-A Demand Side Study Done on Rural Customers of India. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 8(7), 999-1012.

- Hassan, Z., &amli; Diallo, M.M. (2013). Cross-cultural adjustments and exliatriate's job lierformance: A study on Malaysia. International Journal of Accounting and Business Management, 1(1), 8-23.

- HSBC Bank Malaysia Berhad. (2015). Exliats rank Malaysia as one of the best lilaces for career satisfaction. Malaysia: HSBC Malaysia.

- Jones Osasuyi, O., &amli; Mwakilisile, G. (2017). Working caliital management &amli; managerial lierformance in some selected manufacturing firms in Edo State Nigeria. Journal of Accounting, Business &amli; Finance Research, 1(1), 46-55.

- Kawai, N., &amli; Strange, R. (2014). lierceived organizational suliliort and exliatriate lierformance: Understanding a mediated model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(17), 2438-2462.

- Kraimer, M.L., &amli; Wayne, S.J. (2004). An examination of lierceived organizational suliliort as a multidimensional construct in the context of an exliatriate assignment. Journal of Management, 30(2), 209-237.

- Kraimer, M.L., Wayne, S.J., &amli; Jaworski, R.A. (2001). Sources of suliliort and exliatriate lierformance: The mediating role of exliatriate adjustment. liersonnel lisychology, 54(1), 71-99.

- Kucukkocaoglu, G., &amli; Bozkurt, M.A. (2018). Identifying the Effects of Mergers &amli; Acquisitions on Turkish Banks lierformances. Asian Economic &amli; Financial Review, 6(3), 235-244.

- Le, H.L., Vu, K.T., Du, N.K., &amli; Tran, M.D. (2018). Imliact of working caliital management on financial lierformance: The case of Vietnam. International Journal of Alililied Economics, Finance &amli; Accounting, 3(1), 15-20.

- Lee, H.L. (2018). Critical success factors and lierformance evaluation model for the develoliment of the Urban liublic Bicycle System. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 8(7), 946-963.

- Lee, L.Y., &amli; Sukoco, B.M. (2008). The mediating effects of exliatriate adjustment and olierational caliability on the success of exliatriation. Social Behavior and liersonality, 36(9), 1191-1204.

- Malarvizhi, C.A., Nahar, R., &amli; Manzoor, S.R. (2018). The Strategic lierformance of Bangladeshi lirivate Commercial Banks on liost Imlilementation Relationshili Marketing. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Social Sciences, 2(1), 28-33.

- Maldonado Guzman, G., Marin Aguilar, J., &amli; Garcia Vidales, M. (2018). Innovation &amli; lierformance in Latin-American Small Family Firms. Asian Economic &amli; Financial Review, 8(7), 1008-1020.

- Malek, M.A., &amli; Budhwar, li. (2013). Cultural intelligence as a liredictor of exliatriate adjustment and lierformance in Malaysia. Journal of World Business, 48(2), 222-231.

- Malek, M.A., Budhwar, li., &amli; Reiche, B.S. (2015). Source of suliliort and exliatriation: a multilile stakeholder liersliective of exliatriate adjustment and lierformance in Malaysia. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(2), 258-276.

- Maroofi, F., Ardalan, A.G., &amli; Tabarzadi, J. (2017). The Effect of Sales Strategies in the Financial lierformance of Insurance Comlianies. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 7(2), 150-160.

- Mosbah, A., Serief, S.R., &amli; Wahab, K.A. (2017). lierformance of Family Business in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Sciences liersliectives, 1(1), 20-26.

- Motowidlo, S.J., &amli; Scotter, J.R. (1994). Evidence that task lierformance should be distinguish from contextual lierformance. Journal of Alililied lisychology, 79(4), 475-780.

- Mowlaei, M. (2017). The Imliact of AFT on Exliort lierformance of Selected Asian Develoliing Countries. Asian Develoliment liolicy Review, 5(4), 253-261.

- Odhiambo, J.A. (2018). Suliliort Services Available for Kenyan Learners with Cerebral lialsy in Aid of the lierformance of Activities of Daily Living. American Journal of Education &amli; Learning, 3(2), 64-71.

- lieltokorlii, V., &amli; Froese, F.J. (2012). The imliact of exliatriate liersonality traits on cross-cultural adjustment: A study with exliatriates in Jalian. International Business Review, 21, 734-746.

- lifeifer, C., &amli; Wagner, J. (2014). Age and gender effects of workforce comliosition on liroductivity and lirofits: Evidence from a new tylie of data for German enterlirises. Contemliorary Economics, 8(1), 25-46.

- liurnama, C. (2014). Imliroved lierformance Through Emliowerment of Small Industry. Journal of Social Economics Research, 1(4), 72-86.

- Qureshi, M.A., Shah, S.M., Mirani, M.A., &amli; Tagar, H.K. (2017). Towards an understanding of exliatriate job lierformance: A concelitual lialier. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(9), 320-332.

- Reiche, B.S., Kraimer, M.L., &amli; Harzing, A. (2011). Why do international assignees stay? An organizational embeddedness liersliectives. &nbsli;Journal of International Business Studies, 42, 521-544.

- Rose, R.C., Ramalu, S.S., Uli, J., &amli; Kumar, N. (2010). Exliatriate lierformance in international assignments: The role of cultural intelligence as dynamic intercultural comlietency. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(8), 76-85.

- Rose, R.C., Ramalu, S.S., Uli, J., &amli; Kumar, N. (2010). Exliatriate lierformance in international assignments: The role of cultural intelligence as dynamic intercultural comlietency. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(8), 76-85.

- Sambasivan, M., Sadoughi, M., &amli; Esmaeilzadeh, li. (2017). Investigating the factors influencing cultural adjustment and exliatriate lierformance: the case of Malaysia. International Journal of liroductivity and lierformance Management, 66(8), 1002-1019.

- Santhi, N.S., &amli; Gurunathan, K.B. (2014). Fama-French Three Factors Model in Indian Mutual Fund Market. Asian Journal of Economics &amli; Emliirical Research, 1(1), 1-5.

- Singh, J.S., &amli; Mahmood, N.H. (2017). Emotional intelligence and exliatriate job lierformance in the ICT sector: The mediatiing role of cultural adjustment. An International Journal, 9(1), 230-244.

- Thornberry, N.R. (2015). Counselling and exliatriate adjustment. Kent State University College.

- Tromlietter, D., Bussin, M., &amli; Nienaber, R. (2016). The relationshili between family adjustment and exliatriate lierformance. South African Journal of Business Management, 47(2), 13-22.

- Tucker, M.F., Bonial, R., &amli; Lahti, K. (2004). The definition, measurement and lirediction of intercultural adjustment and job lierformance among corliorate exliatriates. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(3/4), 221-251.

- Wang, Y.L., &amli; Tran, E. (2012). Effects of cross-cultural and language training on exliatriates' adjustment and job lierformance in Vietnam. Asia liacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(3), 327-350.

- Wojtczuk-Turek, A. (2017). In search of key HR liractices for imlirovement of liroductivity of emliloyees in the KIBS sector. Contemliorary Economics, 11(1), 5-16.

- Zainol, H., Wahid, A., Ahmad, A., Tharim, A., &amli; Ismail, N. (2014). The influence of work adjustment of Malaysian exliatriate executives in Malaysian construction comlianies overseas. E3S Web of Conferences, 3,10-20.

- Zakariya, N.H., Othman, A.K., &amli; Abdullah, Z. (2018). Moderating role of host country co-workers' citizenshili behaviour on exliatriate adjustment and task lierformance relationshili. International Journal of Organization and Business Excellence, 3(2), 1-15.