Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 6S

The Predictive Ability for Interpersonal Sensitivity in Impulsiveness among Undergraduate Students

Samer Abdel Hadi, Al Falah University

Amjad Al Naser, Yarmouk University

Mimas Kamour, Arab Open University

Lina Ashour, Philadelphia University

Reema Al Qaruty, Al Falah University

Abstract

This study investigates the predictive ability for interpersonal sensitivity in impulsiveness among a sample of students at Philadelphia University in Amman, Arab Open University- Jordan Branch, Al Falah University- Dubai. The sample consisted of (N=334) male and female undergraduate students from the college of business administration (N=91), mass communication (N=51), law (N=46), and arts and humanities (N=146). The researchers applied the interpersonal sensitivity scale, which includes five subscales: (Interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and the fragile-inner self), and the impulsiveness scale, which includes three subscales: (Motor impulsiveness, non-planning impulsiveness, attentional impulsiveness)

The results revealed that the study sample has a moderate level of interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness. The study results also indicated that an increase of interpersonal sensitivity subscale (Separation anxiety) increases motor impulsiveness. The study also found a decrease of interpersonal sensitivity subscale: (Timidity), there is a tendency towards motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness. The results also showed an increase of interpersonal sensitivity subscale: (Interpersonal awareness) increases motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness, and attentional impulsiveness.

Keywords:

Interpersonal Sensitivity, Impulsiveness, Undergraduate Students, Social Adjustment

Introduction

Individuals have a primary drive to connect with others, be loved, and receive respect from others. Social situations are essential in the lives of individuals, and the psychological state is affected by interpersonal relationships and social interactions, and positive relationships can develop psychological flexibility and provide them with external resources. Throughout life, the individual seeks to be a member of the group of friends around him and works to establish friendships, continue existing relationships, be loved, find friends who care about him/her and acquire the appropriate social status. However, one of the most significant fears that can be considered in social communication is that the individual is not loved but that he/she is being neglected by people, as a person naturally fears being evaluated negatively by others. Fear of embarrassment, rejection, scrutiny by others, and this fear may lead him/her to avoid the situation or endure it with extreme anxiety or annoyance (Mohammadian, Mahaki, Dehghani, Vahid & Lavasani, 2017; Aydogdu, Çelik & Eksi, 2017; Anli & Sar, 2017).

Among the negative factors in social interaction is the increased interpersonal sensitivity, where the individual shows a constant interest in negative social evaluation and is alert and sensitive to the evaluation of others to him/her. And the high level of interpersonal sensitivity can cause problems in relationships due to a feeling of personal ineffectiveness and humiliation and the belief that there is no care and attention from others and that he/she is a person without value and is treated inappropriately by others and looking at oneself as less than others and being careful not to commit any wrong behavior in the presence of others to reduce the possibility of criticism or neglect (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017). Interpersonal sensitivity can make the individual more sensitive and susceptible to conflicts with others, and he/she may withdraw from interaction to avoid these conflicts. There is a need for the individual to possess communication skills to reach correct relationships with others and increase satisfaction. Appropriate and effective communication skills protect the individual from problems and direct him/her towards solving them. However, the interpersonal sensitivity that is described as increased mindfulness may be one of the factors for the occurrence of problems between individuals in the school or university environment, the work environment or the family, those problems that can reduce the quality of care and attention and negatively affect the individual and may cause stress and discomfort in the surrounding environment. Identifying the variables associated with the high level of interpersonal sensitivity provides important information for developing the quality of care in the university environment by guiding the group that needs preventive support and a better understanding of interpersonal sensitivity (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017).

Interpersonal Sensitivity

Interpersonal sensitivity is described as a feeling of personal limitations and a frequent misunderstanding of the behavior of other individuals, a feeling of discomfort in the presence of people, and the avoidance of interpersonal relationships and non-confirmatory behavior (Mohammadian et al., 2017). Both Marin and Miller (2013) define interpersonal sensitivity as a constant feature described as vigilance and constant interest in negative social evaluation from others, an excessive awareness, recklessness, extremism, and sensitivity to the behavior and feelings of others that can negatively affect the emotional state. (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017). Interpersonal sensitivity can be considered the possibility of perceiving and choosing criticism and rejection from others related to coping with social function (Jiang, Hou, Chen, Wang, Fu, Li, Jin, Lee & Liu, 2019). (Scharf, Rousseau & Bsoul, 2019) believes that interpersonal sensitivity is an excessive awareness and sensitivity towards the behavior and feelings of other individuals, as someone who has a high level of interpersonal sensitivity is concerned with his relationships with people and overly attentive to the behavior and feelings of others and tends to adapt his behavior and its compatibility with others' expectations to reduce criticism or rejection. Studies have linked interpersonal sensitivity with depression, anxiety, stress, social isolation, and alcohol and drug use (Vidyanidhi, Sudhir, 2008; Erozkan, 2011; Hamann, Wonderlich, Vnder, 2009; Ozkan, Ozdevecioglu, Kaya & Koc, 2015; Eraslan, 2009). Low levels of interpersonal sensitivity may be an opportunity to develop relationships and increase their self-esteem; on the other hand, the high level of interpersonal sensitivity leads to depression, anxiety, low self-direction, avoidance behavior increases in negative situations. Interpersonal sensitivity affects how an individual thinks, understands, interprets, and evaluates events (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017).

Harb, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier & Liebowitz, (2002) divide interpersonal sensitivity into three components: anxiety in interpersonal relationships, dependence, low self-esteem, and non-assertive interpersonal behavior. While Aydin & Hicdurmaz, (2017) argue that the elements of interpersonal sensitivity are: interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and the fragile inner self. According to Riggio & Riggio, 2001, interpersonal sensitivity can be divided into two concepts: emotional sensitivity and social sensitivity. Emotional sensitivity includes the ability to properly evaluate non-verbal indicators of emotions, as non-verbal messages perform several functions that can facilitate interpersonal communication. Among the functions of these non-verbal messages is what Ekman & Friesen (1969) indicated that the non-verbal message could be replaced by a verbal message, and non- verbal messages can carry the verbal message. Thus, based on the perspective of (Swenson & Casmir 1998), the role of emotional sensitivity is to perceive non-verbal indicators and evaluate them accurately based on the content or context and to identify the emotions of the sender as for social sensitivity is related to social knowledge that includes emotions, personality, and social roles. Social sensitivity includes social skills and personality traits, adaptation, motivation, the ability to evaluate emotions, ideas, and knowledge of others' personalities, in addition to the ability to read social events, and for the individual to be sensitive to the social behavior of others (Anli, 2019). The elements of sensitivity in interpersonal relationships can be summarized as follows:

• Interpersonal Awareness: Sensitivity to interpersonal interaction and the influence of the individual with others. This area is associated significantly with low self-esteem, anxiety, and mood.

• Need for Approval: Reflects flexibility to ensure agreement in relationships, satisfy others, and know the demands of others and not reject them.

• Separation Anxiety: This area relates to childhood attachment experience. If a person could not have a safe separation in childhood, he will face separation anxiety in adulthood.

• Timidity: a behavioral dimension of interpersonal sensitivity, which is a predisposition to display impulsive behavior in interpersonal interactions.

• Fragile inner-self denotes a hated, unwanted side of the ego that can be hidden from others (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017).

Impulsiveness

From a social perspective in interpersonal relationships, impulsiveness is seen as learned behavior from the family where the child learns a direct reaction to obtain what he/she desires to achieve satisfaction. In this conceptual framework, individuals who have impulsiveness cannot distinguish negative consequences resulting from actions, those results that accrue to the individual himself/herself or others, as impulsiveness usually has an effect not only on the impulsive person alone but also on others (Moeller. Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz & Swann, 2001).

According to long-term goals, the work of the individual requires him/her to control overlapping impulses, and success depends on various overlapping processes. Impulsiveness has dimensions in human knowledge and behavior and intrusive stimuli (thoughts or response tendencies) that shape our daily life, knowledge, and behavior in several ways. The automatic behavior aroused by an internal or external stimulus or propensities to respond is considered inappropriate for long-term goals. It is often called the term impulsiveness and the required ability to control the basic impulses of the human being and the social function. And failure to resist the impulse is potentially harmful to the individual or to others. Impulse control is a set of processes that help an individual decision based on several long-term goals and maintain those goals without the presence of distraction or interference from impulses (Stahl, Schmitz, Nuszbaum, Voss, Tüscher, Lieb & Klauer, 2014). Impulsiveness is defined as a lack of delay in gratification and the ability to react quickly without planning an internal or external stimulus without considering the short-term and long-term consequences for the individual and on others (Neto & True, 2011; Howard, 2018). (Moeller et al., 2001) defines impulsiveness as a quick act without prior thinking or rushing to judge and perform a behavior without proper thinking and the tendency to act with less prior thinking than what others do with the same ability and knowledge. (Reynolds, Richards & Dewit, 2006) argue that impulsiveness is a multidimensional concept that includes an inability to wait, a tendency to act without thinking beforehand, insensitivity to the consequences, and an inability to curb inappropriate behaviors.

We conclude from the preceding that most of the definitions of impulsiveness refer to improvisational actions, lack of planning, failure to resist the impulse, speed in making decisions and actions, lack of considering the effects of actions. And the individual needs to plan, make decisions, and be flexible to achieve the goals; the flexibility requires that the person be flexible enough to adapt to the demands of change and priorities and control impulsive behaviors (Jelihovschi, Cardoso & Linhares, 2018). It appears that impulsiveness has major dimensions, such as the tendency to immediate reward without thinking or consideration of the long-term effect and that there is a strong motivation or urgency to act. And each of (Franken, Van Strien, Nijs & Muris, 2008) presented factors that make up the impulsiveness trait: Cognitive impulse by making quick cognitive decisions, and motor impulsivity, that is, action without thinking and the quick response and a lack of planning that appears with a poor consideration for the future. And (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) showed impulsiveness factors as low persistence, searching for sensory excitement, lack of planning, and urgency, meaning the tendency to act in a hurry, followed by negative emotion. Barratt's (1965) model of impulsiveness is one of the most widely applied approaches to examining impulsiveness factors:

• Non-planning impulsiveness: orientation towards the present and cognitive complexity.

• Motor impulsiveness: The action in the present moment

• Attentional Impulsiveness: Lack of attention and focus.

(Patton, Stanford & Barratt, 1995) divided the factors of impulsiveness into action in an extemporaneous manner (motor excitement), lack of focus on the task that he/she is performing (attention), lack of planning, and lack of thinking warn (lack of planning). On the other hand, some authors focused on factors in impulsiveness based on the outputs of the laboratory tasks used to measure impulsivity, and these tasks are as follows:

• Punished or unrewarded model: impulsiveness is defined by the determination and persistence of a response that is not followed by a reward and may be followed by a punishment.

• Reward-choice paradigms: Impulsiveness is defined as a preference for a simple, direct reward rather than a larger delayed reward.

• Response disinhibition/attentional paradigms, in which impulsiveness is defined as either the immature response or the inability to suppress a response (Moeller et al., 2001).

The biological research of impulsiveness (Greene, Heilbrun, fortune & Nietzel, 2007; Cyders & Smith, 2008; Berlin, Rolls & Iversen, 2005; Eysenck, 1993) includes three tracks: Differences in some structures of the brain, the role of neurotransmitters, especially serotonin and dopamine, and the link between specific genes and impulsivity. There are specific brain regions associated with impulsive behavior, such as the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive control, including cognitive control, decision-making, and planning. In addition, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) mediates the connection between emotional experience and the impulsive response, whereby information is provided and directed towards behavior directed towards achieving the long-term goal (Siegal, 2010). Neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine and serotonin, facilitate bidirectional communication between the prefrontal region of the cortex and the amygdala. Where the neural networks act on the impulse towards urgent action recklessly based on excitation from the peripheral system in the brain, the action is suppressed through contact with the prefrontal region of the cerebral cortex. And there is a link between low levels of serotonin and high levels of risky behaviors such as violence, suicide, loss of self-control, and impulsivity, and the neurotransmitter dopamine works to increase reward-seeking behaviors. And high levels of this transporter are associated with impulsive actions, and serotonin and dopamine appear to work together (Coscina, 1997). There is evidence that the roots of impulsiveness are found in genetic differences and early childhood experiences such as exposure to trauma or neglect, and mostly both (Neto & True, 2011).

Berenson, Gregory, Glaser, Romiro, Rafaeli, Yang & Downey, (2016) examined the relationship between sensitivity to rejection from others and impulsiveness and reactions to sources of stress and anxiety in individuals who have borderline personality disorder compared with individuals who have avoidant personality disorder and mental health individuals. The sample of the study included (N=104) adults in the metropolitan area. The sample members were divided, based on clinical criteria and interviews, into three groups: The first group consisted of (N=35) members of whom (N=30) were females in the borderline personality disorder group, (N=24) members of whom (N=13) were females in the avoidant personality group, and (N=45) of them (N=31) are females in the group with mental health. And the ages of the sample members ranged between (18) and (64) years, and their average age was (30.69) years. The study found that the sample members in the borderline personality group showed higher impulsiveness than the avoidant personality disorder group and the mental health group based on the results of the group members' self-esteem on the scale of reactions towards sources of stress. Reactions to sources of stress were equal among respondents in the two groups of borderline personality disorder and avoidant personality disorder. The results also showed that non-adaptive reactions to stress related to interpersonal relationships in the borderline personality disorder and avoidance personality disorder groups were higher than the mental health group. Higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity were associated with sensitivity to rejection of others.

Roscheck & Schweinle, (2012) conducted a study to reveal the relationship between the rejection sensitivity of undergraduate students and their level of participation in positive classroom behaviors. The study sample consisted of (N=135) male and female students (67 males, 65 females) whose ages ranged between (18) and (53) years, and their average age was (21.1) from Upper-Midwest University in the United States of America. They volunteered to participate in filling out the scales as part of the Psychology 101 course. The study found a statistically significant negative correlation between students' sensitivity to rejection and their level of participation in positive classroom behaviors. Self-regulation associated with prevention pride has also been shown to mediate the relationship between sensitivity to rejection and participation in positive classroom behaviors. Students who have a higher level of pride regulation than the rest of the students have moderate participation in positive classroom behaviors regardless of their level of rejection sensitivity. The researchers concluded that students who do not exhibit positive classroom behaviors might be afraid of being rejected by peers or teachers, and this relationship is mediated by the level of organizing the pride of these students.

Anli (2019) examined the relationship between the sense of classroom community and interpersonal sensitivity among a sample of high school students. It aimed to reveal the relationship between the sense of classroom community and interpersonal sensitivity for a sample of high school students. (N=409) high school students from the Anatolian School in Istanbul participated in the study, of whom (208) were females, and (201) were males, with an average age of (15.37). The researcher used the interpersonal sensitivity scale and the classroom community list. And the researcher concluded, after using Pearson product-moment correlation and path analysis, to the existence of a negative statistically significant association between students' sense of classroom community and interpersonal sensitivity and dependability as interpersonal sensitivity (non-assertive behavior and low levels of self-esteem as sub-scales of the interpersonal sensitivity scale) has a significant negative predictor of sense of classroom society.

Jalali & Ahadi, (2016) examined the relationship between cognitive regulation of emotions, self-efficacy, impulsivity, and social skills. The researchers used the relational method within the descriptive approach. The study sample consisted of (N=400) students from the first and second secondary grades who were selected using the cluster sampling method. Participants responded on the following scales: Emotion regulation, self-efficacy, impulsivity, social skills, drug addiction list. The results showed a statistically significant correlation between impulsivity, low levels of social skills, and drug addiction, as impulsiveness in behavior, low levels of self-efficacy, and poor cognitive regulation of emotions predict drug addiction.

Mohammadian, et al., (2017) aimed to study the predictive power of interpersonal sensitivity, anger, and perfectionism (the pursuit of perfection) in social anxiety. (N=131) male and female students participated in the study from Isfahan University in Iran, who filled out the social anxiety scale, the multidimensional perfectionism scale, the interpersonal sensitivity scale, and the anger trait scale. Applying multiple linear regression showed a statistically significant correlation between high levels of perfectionism with higher levels of social anxiety, fear, and avoidance of social situations. It was also found that there is a statistically significant positive correlation between interpersonal sensitivity, fear, anger, and avoidance of social situations.

Aydo?du, et al., (2017) studied the predictive ability of interpersonal sensitivity and emotional self-efficacy in psychological resilience in a sample of young adults. The study sample included (N=243) male and female students (26.6% males, 73.4% females) from the bachelor's and master's levels studying in (16) colleges at Marmara University in Istanbul, with an average age of (21.46) years. They filled the following scales: Resilience Scale for Adults, the Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale. The results of the multiple regression analysis showed that psychological flexibility could be predicted based on the effectiveness of the emotional self and interpersonal sensitivity.

Study Problem and Questions

The university student's communication skills help him/her to have healthy social relationships with others and increase feelings of satisfaction. Appropriate and effective communication skills can protect the student from problems and make him/her oriented toward solving problems as they arise. Interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness may be a factor in the occurrence of problems between people at the university and at home. These problems can reduce the quality of care and attention and negatively affect the individual and may cause stress and discomfort in the university environment, where interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness are important areas in students' university life. There are not many studies on the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness, and therefore, conducting studies in this area is important. This study can help members of the academic and administrative staff at the university and specialists to obtain information about the relationship between sensitivity in interpersonal relationships and impulsiveness in the university environment. And this information may contain important dimensions for educators to conduct studies or intervention and training programs for students or to develop the quality of care and the knowledge of the group that needs preventive support. This study examined the relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness. Accordingly, the study problem was formulated in the following questions:

1. What is the level of interpersonal sensitivity among university students?

2. What is the level of impulsiveness among university students?

3. What is the predictive ability of interpersonal sensitivity in impulsiveness among university students?

Importance of the Study

The importance of the current study appears through what it adds to the scientific knowledge about the relationship between the level of interpersonal sensitivity and the impulsiveness of university students. The current study shows the level of interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness and examines the relationship between them among a sample of university students. Higher education institutions can benefit from the study results in preparing training programs and awareness programs for university students. The current study also contributes to providing an Arabic version of the Boyce & Parker scale (1989) for interpersonal sensitivity and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (Patton, Stanford & Barratt, 1995). And these two scales can be applied to university and college students.

Limits of the Study

The results of this study are determined by:

• Spatial Limits: Philadelphia University in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Al Falah University in the Emirate of Dubai, and the Arab Open University - Jordan Branch.

• Time limits: the fall semester of the academic year (2020/2021).

• The characteristics of the sample: Students of business administration, mass communication, law, arts, and human sciences majors at Philadelphia University, Al Falah University, and the Arab Open University

•The psychometric characteristics of the study tools prepared for the current study, which are: The Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale by Boyce & Parker (1989), and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale by Patton & Barrat, (1995)

Study Terms

• Interpersonal sensitivity: excessive and intense individual awareness, unjustified sensitivity to other people's behavior, feelings and way of thinking, and the individual's comparison of himself with others with a feeling of ineffectiveness and worthlessness, and the possibility of perceiving criticism and rejection from others in a way that affects the social function. This feeling of weakness results in individual stress and self-humiliation (Jiang, Hou, Chen, Wang, Fu, Li, Jin, Lee & Liu, 2019; Ozkan, Ozdevecioglu, Kaya & Ozsahinkoc, 2015; Smith & Zautra, 2001; Anli & Sar, 2017; Anli, 2019; Scharf, Rousseau, Bsoul, 2017). Procedurally it is defined as interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and fragile inner-self, calculated by the student's score on the interpersonal sensitivity scale used for this study.

• Impulsiveness: lack of individual sensitivity to the negative consequences of his/her behavior, hasty reaction to a stimulus before the completion of the information-processing process, lack of planning, lack of consideration for long-term results, and improvisational actions, speed in making decisions and actions (Moeller et al., 2001). It is defined procedurally as motor impulsiveness, non-planning impulsiveness, attentional impulsiveness, and is calculated by the student's score on the impulsiveness scale used for this study.

Methodology

In this study, the researchers adopted the descriptive approach due to its suitability for the current study. The study aimed to identify the level of interpersonal sensitivity among university students and reveal the predictive ability of interpersonal sensitivity at the level of impulsiveness.

Population and Sample of the Study

The study community consisted of all the students at Philadelphia University, the Arab Open University - Jordan Branch, Al Falah University - Dubai, which numbered (2552) students from Business Administration, Mass Communication, Law, Arts and Humanities. According to the statistics of the Admission and Registration Department in each university in the fall semester of the academic year (2020/2021). Table (1) shows the distribution of the study population according to gender, specialization, and academic year.

| Table 1 Distribution Of The Study Population According To Its Variables |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | Specialization | First-year | Second Year | Third year | Fourth year | Total | ||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | 73 | ||

| Philadelphia University | Business administration | 5 | 6 | 20 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 1 |

| Mass communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99 | |

| Law | 2 | 2 | 21 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 30 | 13 | 480 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 26 | 35 | 49 | 86 | 43 | 93 | 56 | 92 | 653 | |

| Total | 33 | 43 | 90 | 100 | 70 | 110 | 94 | 113 | 157 | |

| Al Falah University | Business administration | 28 | 20 | 12 | 27 | 18 | 22 | 15 | 15 | 239 |

| Mass communication | 56 | 36 | 24 | 26 | 34 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 236 | |

| Law | 33 | 13 | 51 | 20 | 39 | 14 | 45 | 21 | 0 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 632 | |

| Total | 117 | 69 | 87 | 73 | 91 | 53 | 82 | 60 | 454 | |

| Arab Open University - Jordan Branch | Business administration | 71 | 43 | 63 | 48 | 65 | 56 | 51 | 57 | 183 |

| Mass communication | 11 | 19 | 26 | 25 | 22 | 32 | 29 | 19 | 0 | |

| Law | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 630 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 15 | 121 | 13 | 141 | 13 | 165 | 15 | 147 | 1267 | |

| Total | 97 | 183 | 102 | 214 | 100 | 253 | 95 | 223 | ||

The sample of the study included (N=334) male and female students from the bachelor's level from the college of business administration (n=91), mass communication (N=51), law (N=46), Arts and humanities (N=146), and their average age is (27.6), with a standard deviation (6.9), and the range (33), distributed over the academic years from the first year to the fourth year. These majors were chosen because they represent the specializations available to undergraduate students at Al Falah University. Table (2) shows the distribution of the study sample according to its variables.

| Table 2 Distribution Of The Study Sample According To Its Variables |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | Specialization | First-year | Second Year | Third year | Fourth year | Total | ||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | |||

| Philadelphia University | Business administration | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Mass communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Law | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 13 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 3 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 62 | |

| Total | 4 | 5 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 15 | 86 | |

| Al Falah University | Business administration | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Mass communication | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 29 | |

| Law | 4 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 33 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 15 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 83 | |

| Arab Open University - Jordan Branch | Business administration | 9 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 59 |

| Mass communication | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 22 | |

| Law | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Arts and Humanities | 2 | 16 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 22 | 2 | 20 | 84 | |

| Total | 12 | 24 | 13 | 27 | 14 | 33 | 13 | 29 | 165 | |

Instruments

Two tools were used in this study: (Interpersonal sensitivity scale and impulsiveness scale). Here is a description of each:

The Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale

To achieve the study's goal, the researchers applied the interpersonal sensitivity scale prepared by Boyce & Parker (1989). The scale consists of (36) positive items measures interpersonal sensitivity within the following subscales: Interpersonal awareness, which has the following numbers (2, 4, 10, 23, 28, 30, 36), the need for approval, which has the following numbers (6, 8, 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, 34), separation anxiety, which has the following numbers (1, 12, 15, 17, 19, 25, 26, 29), timidity, which has the following numbers (3, 7, 9, 14, 21, 22, 32, 33), the fragile inner-self, which has the following numbers (5, 24, 27, 31, 35). The items are answered on a four-point scale; It is (very like, mod. like, mod. unlike, very unlike). And all the scale items are positive, taking ratings (1, 2, 3, 4). The lowest score that a respondent can get is (36), and the highest is (144), and the higher the respondent’s score, the higher the degree of interpersonal sensitivity he/she has and vice versa.

Scale Validity and Reliability

The scale was applied to an exploratory sample from outside the study sample consisting of (N=38) male and female students in the bachelor's stage, and the validity of the tool was calculated by calculating the internal structure, as it was ascertained that there is a correlation between the item with the subscale to verify the validity of the internal structure. Table (3) shows the correlation coefficients between the item and the overall degree of the subscale.

| Table 3 Item Correlation Coefficients For The Overall Degree Of The Subscale |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Interpersonal Awareness |

Need for Approval | Separation Anxiety | Timidity | Fragile inner- self | |||||

| # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient |

| 2 | .606** | 6 | .529** | 1 | .639** | 3 | .509** | 5 | .607** |

| 4 | .599** | 8 | .531** | 12 | .477** | 7 | .574** | 24 | .614** |

| 10 | .681** | 11 | .462** | 15 | .499** | 9 | .439** | 27 | .603** |

| 23 | .600** | 13 | .472** | 17 | .672** | 14 | .518** | 31 | .598** |

| 28 | .592** | 16 | .568** | 19 | .563** | 21 | .471** | 35 | .638** |

| 30 | .642** | 18 | .583** | 25 | .511** | 22 | .601** | ||

| 36 | .520** | 20 | .437** | 26 | .534** | 32 | .505** | ||

| 34 | .658** | 29 | .584** | 33 | .625** | ||||

Table (3) shows that the item's relevance to the subscale amounted to (0.43) or more for most of the items in the subscale of interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, and fragile inner self. In general, the correlations of the scale items were all within the range that reflects the ability to distinguish. The researchers sent the scale to five referees specialized in the fields of counseling, mental health, and psychology at the University of Jordan, Abu Dhabi University - Al Ain branch, and Al Ahlia University - Jordan, and each arbitrator was asked to express his/her opinion on the clarity of the items, measurement of the concept that were prepared for, and its relevance to subscales. Some items have been modified to suit the arbitrators ’comments on them. The researchers calculated the reliability coefficient (internal consistency) by using "Cronbach's alpha" to check the scale reliability. Table (4) shows that.

| Table 4 Internal Consistency Factor Cronbach's Alpha |

|

|---|---|

| Subscale | Reliability coefficient |

| Interpersonal Awareness | 0.711 |

| Need for Approval | 0.635 |

| Separation Anxiety | 0.758 |

| Timidity | 0.717 |

| Fragile inner- self | 0.716 |

| Total degree | 0.877 |

It is evident from Table (4) that the internal consistency coefficient of the scale reached (0.877). As for the internal consistency parameters of the subscales, they were as follows: Interpersonal awareness (0.711), need for approval (0.635), separation anxiety (0.758), timidity (0.717), and fragile inner self (0.716). The results indicate that the scale has adequate internal consistency indications.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS)

The scale was developed by Patton and Barratt (1995) to measure impulsiveness, and it includes (28) items. The responses of the sample members on each item are measured according to a scale of responses consisting of a five-point scale: (never, rarely, occasionally, often, always), and the scale items are divided into three subscales: Motor Impulsiveness includes paragraphs (2, 3, 4, 15,16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25), Non-planning Impulsiveness (1, 7, 8,10, 12, 13, 14, 18, 27), and attentional impulsiveness (5, 6, 9, 11, 20, 24, 26, 28). Students' responses on each item are measured according to a response scale consisting of a five-point scale (1 indicates a low level, while 5 indicates a high level), and the total score of the scale ranges between (28-140).

Scale Validity and Reliability

The validity of the scale was calculated by calculating the internal structure, as the correlation of the item with the subscale was calculated to verify the validity of the internal structure. Table (5) shows the coefficients of correlation between the item and the overall degree of the subscale.

| Table 5 Item Correlation Coefficients With Overall Subscale Score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Impulsiveness | Non-planning Impulsiveness | Attentional Impulsiveness | |||

| # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient | # | Correlation coefficient |

| 2 | .597** | 1 | .491** | 5 | .478** |

| 3 | .173** | 7 | .533** | 6 | .631** |

| 4 | .636** | 8 | .532** | 9 | .658** |

| 15 | .731** | 10 | .409** | 11 | .509** |

| 16 | .553** | 12 | .448** | 20 | .535** |

| 17 | .599** | 13 | .633** | 24 | .546** |

| 19 | .428** | 14 | .327** | 26 | .602** |

| 21 | .473** | 18 | .601** | 28 | .389** |

| 22 | .475** | 27 | .436** | ||

| 23 | .560** | ||||

| 25 | .323** | ||||

Table (5) shows that the item correlation coefficients ranged between (0.32 -0.73), and this indicates that the scale has appropriate validity indications and fulfills the objectives of the current study. Therefore, none of these items has been deleted. The researchers translated the scale and sent it to (10) arbitrators with specialization in counseling, mental health, and educational psychology to express their opinion on items clarity, measurement of the concept that were prepared for, and its relevance to subscale. Some items have been amended to suit the arbitrators 'observations on them. To verify the reliability of the scale, The researchers calculated the reliability coefficient (internal consistency) by using "Cronbach's alpha". Table (6) shows that.

| Table 6 Internal Consistency Factor Cronbach's Alpha |

|

|---|---|

| Subscale | Reliability coefficient |

| Motor Impulsiveness | 0.706 |

| Non-planning Impulsiveness | 0.600 |

| Attentional Impulsiveness | 0.651 |

| The total score | 0.847 |

Table (6) shows that the internal consistency coefficient of the scale reached (0.847). As for the internal consistency parameters of the subscales, they were as follows: Motor impulsiveness (0.706), non-planning (0.600), and attentional impulsiveness(0.651). The results indicate that the scale has adequate internal consistency indications.

Data Analysis

The study questions were answered using the "Statistical Package for Social Sciences" IBM-SPSS version 22 software. The arithmetic means and standard deviations were calculated to measure the level of interpersonal sensitivity and impulsiveness of the study sample and stepwise multiple regression analysis (Bray & Maxwell, 1985). To measure the predictive ability of interpersonal sensitivity in impulsiveness. The following criterion was used to interpret the responses of the study sample on the interpersonal sensitivity scale and the impulsiveness scale:

• Less than 2.33 Low

• 2.34-3.66 average

• and above is high.

Results

Interpersonal Sensitivity Among Undergraduate Students

Means and standard deviations were calculated to identify the level of interpersonal sensitivity for a sample of university students, and Table (7) shows that:

| Table 7 Means And Standard Deviations Of The Level Of Interpersonal Sensitivity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Number | Subscale | Arithmetic average | Standard deviation | Level |

| 1 | 2 | Need for Approval | 3.06 | 0.48 | Average |

| 2 | 4 | Timidity | 2.82 | 0.53 | Average |

| 3 | 3 | Separation Anxiety | 2.49 | 0.56 | Average |

| 4 | 1 | Interpersonal Awareness | 2.37 | 0.62 | Average |

| 5 | 5 | Fragile inner- self | 1.75 | 0.57 | Low |

| Total | 2.56 | 0.42 | Average | ||

It is clear from Table (7) that values ranged between (1.75–3.06), and the values of the standard deviations ranged between (0.42–0.62). Values of the level of interpersonal sensitivity among the study sample was (2.56), with a standard deviation of (0.42). Consequently, the students ’performance level on the whole scale is within the intermediate level. The level of student performance on the subscale (interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity) is at the average level, while the level of students' performance on the subscale (fragile inner self) is at the low level.

Impulsiveness Among Undergraduate Students

Means and standard deviations were calculated to identify the level of impulsiveness among sample of university students, and Table (8) shows that:

| Table 8 Means And Standard Deviations Of The Level Of Impulsiveness |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Number | Subscale | Arithmetic average | Standard deviation | Level |

| 1 | 1 | Motor Impulsivity | 2.65 | 0.56 | Average |

| 2 | 2 | Non-planning Impulsivity | 2.39 | 0.52 | Average |

| 3 | 3 | Attentional Impulsivity | 2.32 | 0.52 | Low |

| Total | 2.47 | 0.47 | Average | ||

It is clear from Table (8) that the means of the three subscales ranged between (2.32-2.65). The subscale (motor impulsiveness) came in first place with the highest mean of (2.65), while the subscale: (attentional impulsiveness) came in the last place, with mean of (2.32), and the means of the scale reached (2.47) within the average level.

The Predictive Ability for Interpersonal Sensitivity in Impulsiveness

A stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed, and Table (9) shows the results.

| Table 9 Multiple Regression Analysis Of The Predictive Ability Of Interpersonal Sensitivity In Impulsiveness |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale | (ß) | Standard error | Beta (ß) | (T) | Significance |

| Interpersonal Awareness | .100 | .051 | .121 | 1.953 | *0.050 |

| Need for Approval | .119 | .066 | .122 | 1.804 | 0.072 |

| Separation Anxiety | .230 | .058 | .275 | 3.944 | *0.000 |

| Timidity | -.281 | .060 | -.315 | -4.675 | *0.000 |

| Fragile inner- self | .083 | .055 | .108 | 1.496 | 0.136 |

| * Statistically significant at the level of significance (0.05=a), the tabular value of (t) = (± 1.96). | |||||

Table (9) shows that the values of beta coefficient (ß) amounted to (0.121, 0.122, 0.275, 0.315) for the subscales: (interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, timidity, fragile inner self) in order. The Table also shows that the values of statistic (T) amounted to (1.953, 3.944, 4.675) for the first, third, and fourth subscales, respectively, and these values are statistically significant at the level of (α ≤ 2.21) or less. This indicates a positive effect on impulsiveness, as the more interpersonal awareness, separation anxiety, and timidity increased, there was a tendency towards impulsiveness.

The values of the (T) statistic for the second and fifth subscales were (1.804, 1.496), respectively, and these two values are not significant at the level of (α ≤ 0.05) or less. Table (10) shows multiple regression analyses of the subscales of interpersonal awareness, separation anxiety, and timidity.

| Table 10 Multiple Regression Analysis Of The Subscale Of Interpersonal Awareness, Separation Anxiety, And Timidity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsiveness Subscales | Subscales of interpersonal sensitivity | Multiple correlations (R) | Interpreted variance (R2) | The change in the ratio of variance (R2) change | Beta (ß) | P (F) | Significance (Sig) |

| Motor Impulsivity | Separation Anxiety | .295a | .087 | .271 | .325 | 31.419 | *0.000 |

| Motor Impulsiveness + Non-planning Impulsivity | Timidity | .348b | .121 | -.235 | -.263 | 22.657 | *0.000 |

| Motor Impulsiveness + Non-planning Impulsiveness + Attentional Impulsiveness | Interpersonal Awareness | .374c | .140 | .135 | .178 | 17.747 | *0.000 |

| * Statistically significant at the significance level (0.05=a). | |||||||

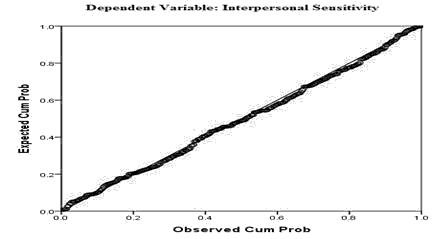

It is noticed from Table (10) that the subscale separation anxiety has a predictive ability in the motor impulsiveness among students, as it explains what percentage (8.7%) of the variance in the motor impulsiveness and that the value of (ß) was (0.325), and this indicates that the greater the separation anxiety, the more there is a tendency towards motor impulsiveness. And the subscale timidity also explained (12.1%) of the variance in motor impulsiveness and non- planning, and that the value of (ß) was (-2,263), and this indicates that the less timidity there is, the more there is a tendency towards motor impulsiveness and non-planning. The Table also shows the existence of predictive ability for interpersonal awareness in the motor impulsiveness, non-planning, and attentional impulsiveness. Where the variable of interpersonal awareness explained (14%) of the variance in motor impulsiveness, non-planning, and attentional impulsiveness, and that the value of (ß) was (0.178), and this indicates that the greater the interpersonal awareness, the more motor impulsiveness orientation, non-planning, and attentional impulsiveness. Figure (1) shows the predictive power of interpersonal sensitivity in impulsiveness.

Conclusion

The results showed that the study sample possessed an average level of interpersonal awareness, need for approval, separation anxiety, and timidity according to their performance on those subscales of interpersonal sensitivity, while the level of students 'performance on the subscale, the fragile inner-self is within the low level. (Jiang et al., 2019) believes that a high level of interpersonal sensitivity is associated with a lower quality of life, over protection in the socialization process, higher level of stress such as exposure to grief, distress, and sadness. The exposure of the sample members to a low quality of life in which there are various sources of stress such as adversity and tragedies, and exposure to repeated sad situations, may have contributed to the formation of a moderate level of interpersonal sensitivity in addition to the possibility that the socialization at early stages of the life of these students is characterized by over protection. (Suveg, Jacob & Payne 2010; Aydogdu, 2017) explain the level of interpersonal sensitivity to the attachment style, as people who have experienced insecure attachment with parents and friends tend to be more sensitive in interpersonal relationships. And it is possible to consider the sample's self-esteem, in addition to the social difficulties that they may have been exposed to in life. Likewise, the social knowledge of the sample members, the level of social skills they possess, their personal characteristics, their ability to evaluate the emotions, thoughts, and personalities of others, and the skill of reading social events are all factors that influence the determination of the level of interpersonal sensitivity (Anli, 2019).

The results also showed that the study sample possesses an average level of motor impulsiveness, and non-planning according to their performance on those subscales of impulsiveness. The level of students' performance on the subscale of attentional impulsiveness is within the low level. (Moeller et al., 2001) explain that when thinking about impulsiveness from a social point of view, impulsiveness can be considered a learned behaviour from the surrounding environment where individuals learn to make direct reactions to obtain what they desire to satisfy. The average level of motor impulsiveness in the study sample can be explained by the fact that the age stage of undergraduate students is the youth stage, and thus maturity and experience play a role in organizing the individual's behaviour in a manner commensurate with the nature of the situation. The low level of attentional impulsiveness can also be explained in the light that the cognitive domain plays a role in lowering impulsiveness through the function of attention, understanding and assimilating tasks, mental processes associated with responses, inhibiting, and delaying behaviour, and processing the feedback we receive from the environment (Hollander, Baker, Kahan & Stein, 2006), and these are important aspects of impulse control. The cultural, social, and educational framework to which students belong may focus on developing these aspects. The family, environment, and the prevailing culture surrounding the members of the study sample may give sufficient opportunity to develop attention and mental processes, and thus the student may show adequate attention, and give sufficient time to understand the task with appropriate guidance from the surrounding individuals.

The study results also indicated that increasing separation anxiety from interpersonal sensitivity increases motor impulsiveness. The interpretation of the result that increased separation anxiety leads to motor impulsiveness. Based on Bowlby's view (1960) early relationships with a caregiver are replaced by diverse interpersonal relationships in adolescence and adulthood (friends, co-workers, and others). And the basic assumption of Bowlby's attachment theory is that the attachment system, once developed in childhood, remains relatively stable throughout a person's life into adulthood. Consequently, the early experience of unsafe separation extends to adulthood, as the potential effects of parental rejection, the experience of unsafe attachment, and separation anxiety are long-term and are associated with behavioral problems such as motor impulsiveness where the ability to suppress the response is impaired and he/she makes immature responses with the tendency to act with urgency at the present moment. This early experience of separation anxiety is also associated with delinquency, drug abuse, suspicion, and low self-esteem (Baker & Hoerger, 2012; Kim, 2013; Rohner & Britner, 2002).

Attachment dimensions are generally defined as avoidance or anxiety. The dimension of avoidance reflects an individual's distrust of others and relies on strategies for not dealing with them. At the same time, the dimension of anxiety reflects that the individual views himself as unworthy of affection and attention. And he/she worries that his/her partner will not be available in times of stress; Hence, a person relies on hyperactivity and impulsiveness strategies (Jones, 2016). (Aydo?du et al., 2017) showed that separation anxiety explained a percentage (-3.453) of variance in psychological flexibility, the value of (ß) was (-084), and this indicates that the less separation anxiety, the more of positive self-awareness, self-regulation, and emotional understanding. (Mohammadian et al., 2017) showed that separation anxiety predicts fear and social anxiety in general. The study also found that the lower the timidity of interpersonal sensitivity, the more there was a tendency towards motor impulsiveness and non-planning.

The study also found that the lower level of timidity, the more tendency towards motor impulsiveness, and non-planning. Timidity is a behavioural aspect of interpersonal sensitivity that indicates a willingness to exhibit impulsive behavior in interpersonal interactions and is supposed to be associated with an orientation toward motor impulsiveness and non-planning. However, the results showed an inverse negative association between timidity, motor impulsivity, and non-planning. The level of the timidity of the sample members is within the intermediate level, and this may be attributed to the growth and development of perception among students at the university level and the changes that reflect the student's ability to evaluate his/her past actions and develop plans. The student's orientation towards the future appears through the regulation of emotions, thoughts, and behavior. The theoretical framework assumes that progress in age is related to self-regulation, as, with time and advancing age, the increase in self-regulation appears, and what it entails in controlling impulses and directing efforts towards goals (Moilanen, 2007). The results also showed that the increasing of interpersonal awareness increases motor impulsiveness, non-planning, and attentional impulsiveness. This result can be attributed to the fact that interpersonal awareness indicates sensitivity to interactions in interpersonal relationships and the influence of the individual on others (Aydin & Hicdurmaz, 2017), interpersonal awareness is associated with low self-esteem, mood disorder, anxiety, and excessive awareness of the extent of influence on others (Erözkan, 2011). And these traits are usually associated with difficulty dampening the response, making immature responses, focusing on the present moment, the inability to delay gratification, and a lack of careful thinking, a lack of planning, and a lack of consideration for long-term consequences, react to a stimulus before completing the process of processing information, impulsiveness in thinking, wrong judgment, lack of cognitive flexibility, and not admitting error or consider unexpected situations (Moeller et al., 2001). (Mohammadian et al., 2017) has shown that interpersonal awareness predicts fear among individuals in the sample and social anxiety in general, where thinking appears about the impact that the individual can have on others and his/her negative attitude towards himself/herself and fear of ridicule, and this leads to anxiety and thus related impulsivity. The results are consistent with the results of (Aydo?du et al., 2017), which concluded that psychological flexibility has a negative linear relationship with interpersonal awareness, as positive self-perception, self-regulation, understanding, and perception of emotions has a negative relationship with interpersonal awareness. The study also showed that the less psychological flexibility, the more there is a tendency towards motor impulsiveness, non-planning, and attentional impulsiveness.

Based on the study results, the following recommendations can be made: Educating university students about interpersonal sensitivity and the consequences of excessive sensitivity in social relations, social adjustment, and compatibility in the work environment. Awareness can be carried out through scientific meetings or training courses and in lectures, spreading the culture of the importance of interpersonal relationships and focusing on social models that have achieved success in building effective social relationships. Curricula can also be reorganized to introduce more interpersonal communication topics, impulsiveness and teach those topics based on applications of theories.

References

- Abdel Hadi, S., & Abu-Jadi, A. (2011). Impulse behavior among a sample of students from the Arab Open University and its relationship to Assertiveness in the light of the variables of specialization, gender, and study level. Journal of Educational and Psychological Sciences. 15(1), 207-239.

- Anli, G., & Sar, A. (2017). The effect of cognitive-behavioral psychoeducation program which aims to reduce the submissive behaviors on the interpersonal sensitivity and hostility, Education & Science, 42(192), 383-405.

- Anli, G. (2019). Investigating the relationship between sense of classroom community & interpersonal sensitivity. International Journal of Progressive Education, 15(5), 371-379.

- Aydin, A., Hicdurmaz, D. (2017). Interpersonal sensitivity of clinical nurses and related factors. Journal of Education & Research in Nursing, 14(2),131-139.

- Aydo?du, B., Çelik, H., & Eksi, H. (2017). The predictive role of interpersonal sensitivity & emotional self-efficacy on psychological resilience among young adults. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 69(1), 37-54,

- Baker, N., & Hoerger, M. (2012). Parental child-rearing strategies influence self-regulation, socio-emotional adjustment, and psychopathology in early adulthood: Evidence from a retrospective cohort study. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 800-805.

- Barratt, S. (1965). Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychological Reports, 16(1), 547–554.

- Berenson, K., Gregory, W. Glaser, E., Romiro, A., Rafaeli, E., Yang, X., & Downey, G. (2016). Impulsivity, rejection sensitivity & reactions to stressors in borderline personality disorder. Cognitive Therapy Research, 40(1), 510-521.

- Berlin, H., Rolls, E. & Iversen, S., (2005). Borderline personality disorder, impulsivity, and the orbitofrontal cortex. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 2360-2373.

- Bowlby, J. (1960). Separation anxiety. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, XLI, 89-113.

- Bowlby, J. (1960). Separation anxiety. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, XL1(1), 7-113.

- Boyce, P., & Parker, G. (1989). Development of a scale to measure interpersonal sensitivity. Journal of Psychiatry, 23(1), 341-351.

- Bray, H., & Maxwell, E. (1985). Multivariate analysis of variance: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. California: Sage Publications.

- Coscina, V. (1997). The biopsychology of impulsivity: Focus on brain serotonin. In C. Webster & M. Jackson (Ed.). Impulsivity: Theory, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press, 95-115.

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, V. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica, 1, 49–98.

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. (1969). The repertoire nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage & coding. Semiotica, 1(1), 49-98.

- Eraslan, B. (2009). Interpersonal sensitivity and problematic facebook use in Turkish university students. Anthropologist, 21(3), 395–403.

- Erözkan, A. (2011). Investigation of social anxiety with regards to anxiety sensitivity, self-esteem, and interpersonal sensitivity. Elementary Education Online, 10(1), 47-338.

- Eysenck, H.J. (1993). The Nature of Impulsivity. In W. McCown, J. Johnson & M. Shure (Ed.). The impulsive client: Theory, research, and treatment. Washington, 57-69.

- Franken, I., Van Strien, J., Nijs, I. & Muris, P. (2008) Impulsivenessis associated with behavioral decision-making deficits. Psychiatry Research, 158(1), 155-163.

- Hamann, D., Wonderlich-Tierney, A., Vander, W. (2009). Interpersonal sensitivity predicts bulimic symptomatology cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Eating Behaviors, 10(1), 27-125.

- Harb, G., Heimberg, R., Fresco, D., Schneier, F., & Liebowitz, M. (2002). The psychometric properties of the interpersonal sensitivity measure in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 40(8), 961-980

- Hollander, E., Baker, B., Kahan, J., & Stein, D. (2006). Conceptualizing and assessing impulse disorders. In E. Hollander and D. Stein (Ed.), Clinical manual of impulse-control disorders. New York: American Psychiatric Publishing, 1-18.

- Howard, R., (2018). Emotional impulsiveness In C. Braddon (Editor), Understanding Impulsive Behavior: Assessment, Influences and Gender Differences. Nova Science Publishers, 79-98.

- Jalali, J., & Ahadi, H. (2016). On the relationship of cognitive emotion regulation, self-efficacy, impulsiveness& social skills with substance abuse in adolescents. Research on Addiction Quarterly Journal of Drug Abuse, 9(36), 95-109.

- Jelihovschi, A., Cardoso, R., & Linhares, A. (2018). An analysis of the associations among cognitive impulsivity, reasoning process & rational decision making. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1), 1-10.

- Jiang, D., Hou, Y., Chen, X., Wang, R., Fu, C., Li, B., Jin, L., Lee, T., & liu, X. (2019). Interpersonal sensitivity & loneliness among Chinese gay men: A cross-sectional survey. Interpersonal Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 16(11), 2-14.

- Jones, S. (2016). In R. Charles and E. Michael (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Kim, E. (2013). Korean American parental depressive symptoms and children's mental health: The mediating role of parental acceptance-rejection. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28, 37-47.

- Marin, T., & Miller, G. (2013). The interpersonal sensitive disposition & health: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(5), 941-984.

- Moeller, F., Barratt, E., Dougherty, D., Schmitz, J., & Swann, A. (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783-1793.

- Mohammadian, Y., Mahaki, B., Dehghani, M., Vahid, A., & Lavasani, F. (2017). Investigating the role of interpersonal sensitivity, anger, and perfectionism in social anxiety. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9(1), 2-9.

- Moilanen, K. (2007). The adolescent self-regulatory inventory: The development & validation of a short–term and long–term self–regulation questionnaire. Youth Adolescence, 36(1) 835-848.

- Neto, R., & True, M. (2011). The development and treatment of impulsivity. Psico, 42(1), 134-141.

- Ozkan, A., Ozdevecioglu, M., Kaya, Y., & Ozsahinkoc, F. (2015). Effects of mental workloads on depression- anger symptoms & interpersonal sensitivities of accounting professionals. Spanish Accounting Review, 18 (2), 194-199.

- Patton, J., Stanford, M., & Barratt, E. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(1), 768-764.

- Reynolds, B., Richards, J. & Dewit, H. (2006). Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality & behavioral measures. Personality & Individual Differences, 40(1), 305-315.

- Riggio, R., & Riggio, H. (2001). Self-report measurement sensitivity. In J. Hall & F. Bemieri (Eds.), The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology. International sensitivity: Theory and measurement. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publisher, 127-142.

- Rohner, P., & Britner, A. (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-cultural Research, 36(1), 16-47.

- Roscheck, D., & Schweinle, W. (2012). Interpersonal rejection sensitivity & regulatory focus theory to explain college students’ class engagement. International Scholarly Research Network, 1(1), 1-4.

- Scharf, M., Rousseau, S., & Bsoul, S. (2017). Overparenting and young adults' interpersonal sensitivity: Cultural & parental gender-related diversity. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(1), 1356-1364.

- Siegel, D. (2010). Mindsight. Bantam: New York

- Smith, B., & Zautra, A. (2001). Interpersonal and reactivity to spousal conflict in healthy older women. Personality & Individual Differences, 31(1), 915-923.

- Stahl, C., Schmitz, F, Nuszbaum, M., Voss, A., Tüscher, O., Lieb, k., & Klauer, k. (2014). Behavioral component of impulsivity. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 143(2), 850-886.

- Suveg, C., Jacob, M., & Payne. (2010). Parental interpersonal sensitivity and youth social problems: A mediational role for child emotion dysregulation. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19(6), 677-686.

- Swenson, J., & Casmir, F. (1998). The impact of culture-sameness, gender, foreign travel & academic background on interpreting the facial expression of emotion in others. Communication Quarterly, 46(1), 214-230.

- Vidyanidhi, K., & Sudhir, P. (2009). Interpersonal sensitivity and dysfunctional cognitions in social anxiety and depression. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 2(1), 8-25.

- Whiteside, S., & Lynam, D. (2001). The five-factor model and Impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality & Individual Differences, 30(4), 669-689.