Research Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 4

The Moderating Effects for the Relationships between Green Customer Value, Green Brand Equity and Behavioral Intention

Phuoc Thien Nguyen, Foreign Trade University

Abstract

Due to terrible environmental destructions around the world, more and more people pay attentions to environmental concern. The concept of “green marketing” has emerged as a competitive weapon to win the customers from the market place. However, the interrelationships between customer value, green marketing and social responsibility green brand equity are largely ignored. Through a survey of 236 obtained questionnaires, this study examines how the effects of customer value on brand equity are enhanced by the moderators of green marketing (green promotion and green marketing awareness) and green brand loyalty. This study also verifies how the effects of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions are enriched by self-expressive benefit ad social responsibility. The results from this study revealed that the moderating effects from green marketing and green brand loyalty on the positive influences of customer value toward brand equity are significant. The moderating effects of self-expressive benefit and social responsibility for the influence of brand equity on behavioral intention are significant. The results of this study could be very important for both academicians and practitioners to engage in green marketing activities.

Keywords

Brand Equity, Customer Behavioral Intentions, Customer Value, Green Brand Loyalty, Green Marketing, Moderating Effects.

Introduction

In the late 1960s and the 1970s, the Western people started to recognize that natural resources had been exhausted and inhabitants were coming to a serious deprivation. Against horrible environmental disasters, consumer’s behaviors change toward an increasingly aware of the environmental concerns and wishes of environmental protection (Chen, 2008a; Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, 2012; Matthes et al., 2014; McIntosh, 1991). In the late 1980s, the conception of “green market” has emerged and gradually swept all over the world over the few decade, after the idea of “green marketing” also occurred accordingly has transformed through several stages from the late 1980s, in recent year, because of a vast amount of environmental pollution which obviously linked to industrial manufacturing in the world, the society recognized that the environmental issues have being increased steadily (Chen, 2008a) to integrate every. Consequently, the Kyoto Protocol was adapted in Kyoto, Japan, on 11th December, 1997, which is an international agreement associated with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), is also an international treaty that to reduce emissions of Greenhouse Gases (GHG) by framing binding obligations on industrialized countries, as well as which commits its parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets. Subsequent to Kyoto Protocol, public awareness of “carbon offset” and “carbon neutrality” has attracted people’s attention. Carbon offsetting becomes a popular topic in public. To reduce GHG emissions elsewhere via paying someone else, the aim of buying carbon offsets is to compensates for or “offset” their own emission. Companies purchase large antiquities of carbon offsets to “neutralize” their carbon footprint or that of their products for their so called “eliminate neutrality”, while individuals look for offset their travel emissions (Kollmuss et al., 2008). That is to say, “carbon offset” and “carbon neutrality” are the kind the transformed “green marketing” strategies. Environmental considerations into all aspects of traditional marketing. Subjected to green marketing, environmental issues should be balanced with primary customer needs (Ottman, 2008: 2011).

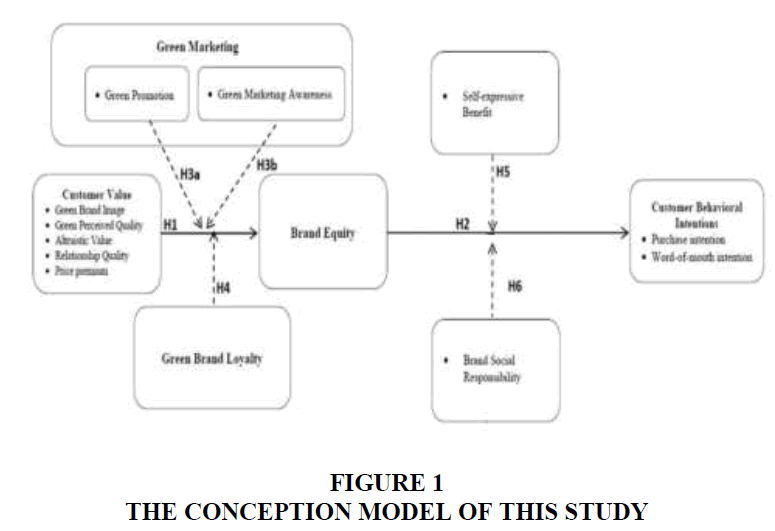

The first and primary purpose of this study is to propose and investigate the moderating effects of green marketing on the relationship between customer value and brand equity. In fact, the relationship between customer value and brand equity is generally proved to be significantly positive (Faircloth et al., 2001; Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). However, the emergence of green marketing certainly implied a lot of changes arising from the relationship in it, when the environmental aspects are taken into account. The concept of customer value will be changed, its influences on the brand equity cannot be exactly the same as before and of course the moderating effects of green marketing on this relationship are in need of further investigations.

Customer value, the difference of what you get from what you give in buying and consuming a good and service, is now developed toward the ‘green’ aspects. The value used for measurement by customer should take into account the environmental issues no matter what the value’s dimensions: emotional, social and or functional (Sweeney & Soutar, 2001). The influences of customer value on brand equity which is defined as the value of having a prominently good brand name will therefore be moderated differently. The green marketing which is considered as the moderator of the above relationship is now included two more factors: the green promotion (offsetting and neutralizing contamination) and green marketing awareness (better recognition and understanding of environment friendly products). All of those changes are taken into account within this study analytical framework.

Another moderator is brand loyalty. Previous studies asserted that brand loyalty is an important factor to create long-term benefits for the organization (Chi et al., 2009; Shirazi & Karimi, 2013). Several previous studies have confirmed the moderating effect of brand loyalty in facilitating the relationship between brand equity and service quality (Ha, 2009). Brand loyalty is enhanced by the trust and commitment toward certain brand. However, there is still a shortage of research discussing brand loyalty as a moderator, especially the brand loyalty in a green market. Thus, this study takes an effort to propose that green brand loyalty should reinforce the relationship between customer value and brand equity. This is in nature another analysis of an old relationship under a new circumstance of environmental factors.

To get a more comprehensive viewpoint of brand equity in a green market, the study extends its analysis to the influences from brand equity on customer behavioral intentions which are represented by purchase intentions and word of mouth intentions. This relationship is actually investigated by a few studies before (Chen & Chang, 2008; Moradi & Zarei, 2011). Thus besides reconfirmation, this study also aims to investigate related moderators of the relationship. Self-expressive benefits and brand social responsibility are taken into account as two major moderators of the relationship between brand equity and customer intentions. Baek et al. (2010) indicted that consumers tend to focus on brand when they purchase high self-expressive products rather than low self-expressive products. Thus, in the case of green purchase, self-expressive benefits could be significant moderating variables. In addition, a company’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can affect customer’s intention to purchase (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). This study takes on step further to evaluate the moderating effects if brand social responsibility for the influence of brand equity on behavioral intention.

It expected that the study results can provide some managerial implications for the companies to conduct their green marketing strategy. It is not just the issue of making profit but also sustaining the profitability through practically applying CSR in their operations.

In summary, based on the above research motivations, this study is centered on the four interacted researched issues:

1. To investigate the relationship between customer values and brand equity

2. To investigate the relationship between brand equity and customer behavioral intentions.

3. To examine the moderating effects of green marketing and green brand loyalty on the effect of customer values and on brand equity.

4. To examine the moderating effects of self-expressive benefits and brand social responsibility for effect of brand equity and on customer behavioral intentions.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Definition of Research Constructs

Customer value

Brand image includes the perceptions of a brand as reflected by the brand associations run in customer memory (Aaker, 1991; Dobni & Zinkhan, 1990; Farquhar, 1989; Keller, 1993; Richardson et al., 1994) and represented the brand concept is functional, symbolic and experiential (Park et al., 1986). Furthermore, brand image performs a key role in the markets where it is difficult to distinguish product and service in tangible quality features (Mudambi et al., 1997). Moreover, green brand image as a set of perceptions of a brand in consumer’s mind that linked to environmental commitments and environmental concerns, and the customers are willing to pay more money for purchasing green products (Chen, 2010).

Perceived quality can be identified a product’s overall excellence or superiority through the consumer’s judgment (Zeithaml, 1988), and also can be defined as the customer’s perception of the overall quality, or superiority or excellence of a product or service regarding its intended purpose, compared to alternatives (Aaker, 1991), and it influences customer’s purchasing decision process (Garretson & Clow, 1999). Furthermore, perceived quality is a higher level abstraction instead of a specific attribute of a product (Zeithaml, 1988). Based on the former discussion above, perceived quality is also one of consumers’ comprehensive perceived values of the product or service, by extension, so is green perceived quality. According to the definition of customer perceived value by Sweeney & Soutar (2001), green perceived quality is categorized as functional value for this study.

Altruism can be defined as helping others via changing the agent’s individual behavior (Haltiwanger & Waldman, 1993), while Altruism model argued social norm is the social behavior standard which is expected by social group, when the social norm has been accepted; individual behavior would be affected by social norm accordingly, and furthermore, the social norm becomes individual norm (Hopper & Nielsen, 1991). In addition, personal environmental behavior and attitude are affected by the norm of social groups; for instance family and friends e.g. (Granzin & Olsen, 1991; Jackson et al., 1993; Oskamp et al., 1991). Moreover, Kotchen (2009), Lee & Wang (2009) demonstrated the influence of altruism on Taiwan people’s attitudes toward green consumption. We can say that altruistic value is also one of consumers’ comprehensive perceived values of the product or service, and it is grouped as social value for this study, in light of the definition of customer perceived value by Sweeney & Soutar (2001).

Smith & Brynjolfsson (2001) asserted that brand is an important attribute affecting consumers’ selection, and brands assist customers to choose a given service or product from a vendor. Brand relationship theory proposes that brand acts as a bridge between suppliers and consumers both (Chang & Chieng, 2006; Davis et al., 2000). Choi et al. (2011) found that brand prestige has been affected directly by brand experience and brand personality, which leads to influence attitudinal brand loyalty and brand relationship quality

Profits can be yielded from price premium, even more, provided resources with which to reinvest in the brand. Furthermore, those resources can be used in such brand-building activates, for example enhancing the product of associations or awareness, or to upgrade the product via research & design activities. A price premium not only provides resources, but can also reinforce the perceived quality (Aaker, 1991). Ailawadi et al. (2003) proposed to measure consumer based brand equity by using a revenue premium measure as an agent. In addition, Aaker (1996) argued the perceived price premium associated with the brand, the attitude toward the brand, or purchase intentions. Therefore, the price premium those consumers are willing to pay for the brand (Park & Srinivasan, 1994).

Brand equity

Lee & Back (2010) asserted significance of brand concept leads competitive advantages. In addition, Yoo & Donthu (2001) brand equity for the customers to differentiate a focal brand and an unbranded product while both have the same standard of product attributes and marketing stimuli. Aaker (1996) identified and developed a valid brand equity measurement system, which dubbed as “The Brand Equity Ten”, and it could be applied across markets and products to enhance firm’s capability. This study defined brand equity as the consumers’ perceived value to distinguish the particular brand from others in marketing campaigns.

Customer behavior intention

Yoshida & Gordon (2012) focused on the aspects of behavioral consequences: repeat purchase intention, word-of-mouth intention, and share-of-wallet, while Cronin et al. (2000) highlighted on the indicators of consumer behavioral intention: repeat purchase and word-of-mouth intention. According to the previous literatures above, this study defined customer behavioral intentions, which consists of purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention, as the customers’ purchasing behavior in marketing campaigns.

As to purchase intention for this study, Ko et al. (2013) asserted that the customer would like to buy the particular product rather than others, even the quality and price are similar with others, meanwhile, they identified word-of-mouth intention which is the customer is willing to recommend this particular product to other people.

Green marketing

Green marketing is a much broader concept, one that can be applied to consumer commodity, industrial goods and even services (Polonsky, 1994). In addition, Ottman et al. (2006) suggested that green marketing strategies can be run successfully and effectively after the planners to distinguish the inherent consumer value of green product attributes or tie desired consumer value to green products, and to draw marketing attention to this consumer value. Furthermore, consumers who are care about environmental issues should already have motivation to look for green products and use it, and are probably paying more attention to green promotional activities (Davari & Strutton, 2014). Based on Davari & Strutton (2014) who defined green promotion containing messages to encourage customers to ‘go-green’ benefits the environment this study clearly defined “carbon offset” and “carbon neutrality” under the category of green promotion for green marketing strategies.

Self-expressive benefit

O’cass & Frost (2002) indicated that consumers prefer brands to improve their social standing and self-image in some way which may influence on consumer’s purchasing. Baek et al. (2010) suggested that consumers tend to focus on both brand credibility and brand prestige when they purchase high self-expressive products.

Green brand loyalty

Aaker (1996) asserted brand loyalty is the core attribute of brand equity. Moreover, a price premium is associated with the brand. Chaudhuri & Holbrook (2001) identified the brand affects customer repurchasing consists of behavioral, or purchase, loyalty, whereas attitudinal brand loyalty includes a degree of dispositional commitment in the light of some unique value linked to the brand. In addition, the customer trusts the brands high and affects are related by both attitudinal and purchase loyalty, it contributes to greater market share and premium prices in the marketplace. This study defined green brand loyalty, which leads the customer to buy the particular green product rather than others, and furthermore keep purchasing it, as the consumers’ brand loyalty intention to green products in marketing campaigns.

Brand social responsibility

A company’s CSR efforts can affect consumers’ intentions to purchase it products (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). Blumenthal & Bergstrom (2003) founded that polymerization of both ‘branding’ and ‘corporate social responsibility’ (CSR) become a key role for organization. Furthermore, Yan (2003) summarized CSR marks the difference between the brands that have captured the imagination of tomorrow’s consumers and those that are proving to be casualties. Based on previous literatures above, those approved the correlations among brand equity, CSR, and purchase intention, while in green marketing; we assumed brand social responsibility might be relevant to purchase intention too. This study defined brand social responsibility as the consumers’ brand perceived value of the green products in marketing campaigns.

The Influences of Customer Values on Brand Equity

Customer value can be conceptualized as a difference between what you get from what you give (Heskett et al., 1994). To some extent, it is like a cost benefit analysis when a consumer decides to buy and consume specific goods and services. Customer value has become a critical concept to understand consumer behavior, for example, shopping behavior and product choice (Matthes et al., 2014). In retailing markets, customer may value goods and services on different aspects, such as product specifications, brands, price and/or quality (Chen, 2010).

Table 1 also presents a stable structure of four dimensions of customer perceived value, which is proposed by Sweeney & Soutar (2001). Almost literature reviews are consensus to use this framework for analyzing the customer value.

| Table 1 A Stable Structure of Four Dimensions | ||

| Dimensions | Definition | Proxies |

| Emotional value | the utility derived from the feelings or affective states that a product generates | Ex: brand image, relationship quality |

| Social value (enhancement of social self-concept) | the utility derived from the product’s ability to enhance social self-concept | Ex: altruistic value |

| Functional value (price/value for money) | the utility derived from the product due to the reduction of its perceived short term and longer term costs | Ex: price premium |

| Functional value (performance/quality) | the utility derived from the perceived quality and expected performance of the product | Ex: perceived quality |

Brand equity is a marketing phrase used to describe the value that a company can achieve from having a well-known brand name, basing on the idea that customers are willing to pay higher for an identical product just because of the product’s brand name (Aaker, 1991: 1996). Brand equity is often believed to contribute to a company’s long-term profitability, as well as, customer purchase intention (Chen & Chang, 2008; Moradi & Zarei, 2011).

From the concepts presented above, the relationship between customer value and brand equity is normally considered significantly positive. In fact, prior studies demonstrated that brand image (a proxy for emotional value) has a positive influence upon brand equity (Faircloth et al., 2001; Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). However, green brand image and green perceived quality are hardly been discussed. Although Chen (2010) addressed that green brand image is associated with green brand equity, the study’s scope of work limited to electronic products in Taiwan rather than green products in general. In addition, the previous study demonstrated the relationship among brand-related and cause-related features on consumer responses to cause-Related Marketing (CRM) (Nan & Heo, 2007), as well as, in light of Aaker (1996), “price premium may be the best single measure of brand equity available”, and satisfaction-relationship quality-retention link (Hennig?Thurau & Klee, 1997). However, all of which much less address about altruistic value, price premium and relationship quality which are related with green products might influence the effects of a brand equity. Consequently, the hypothesis about the relationship between customer value and brand equity is developed as follows:

H1: Customer values (green brand image, green perceived quality, altruistic value, relationship quality, price premium) have positive influences on brand equity.

The Influence of Brand Equity on Customer Behavioral Intentions

Over the past decades, brand equity concept has grown rapidly (Moradi & Zarei, 2011) and has become a key strategic asset which required be monitoring and nurturing by a company pursuing to maximized long-term performance (Sriram et al., 2007). The link between brand equity and behavioral intentions is originated from Theory of Reasoned Action-TORA, emphasizing those customer attitudes and subjective norms are important factors in determining the behavioral intention and ultimate action. Generally, consumer is willing to pay more for just the brand name but not anything else attached to a product (Bello & Holbrook, 1995). The measures of favorable behavioral intentions are categorized in customers: 1) willingness to recommend the service provider to others; 2) repeat purchase intentions; 3) pay price premiums; 4) spend more with the company; and 5) remain loyal (Zeithaml et al., 1996; Cronin et al., 2000).

Previous studies have shown that brand equity has significant influences on consumer’s brand preference and purchase intentions (Chen & Chang, 2008; Moradi & Zarei, 2011). Hoeffler & Keller (2002) maintained that stronger brands give customers confidence in purchase decisions. Strong brands reduce consumption and financial risk and give cognitive and emotional trust in decisions. And many other studies have actually examined the relationship between brand equity and purchase intention in different dimensions such as customer switching or word of mouth (De Matos & Rossi, 2008).

In the context of green marketing, Chen (2010) asserted that green image, green brand trust and green brand satisfaction effect on green brand equity. Hence, this study adopted Cronin Jr et al. (2000)’s positive measurable aspects of behavioral consequences: purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention, to expand exploration further for the relationship between brand equity→ purchase intention; brand equity→ word-of-mouth intention. Hence, the hypothesis about the relationship between brand equity and customer behavioral intentions is developed as follows:

H2: Brand equity has positive influences on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention, word-of-mouth intention).

The Moderating Effect of Green Marketing

This study proposed three variables of green marketing, which consists of green promotion (including carbon offset and carbon neutrality) and green marketing awareness. Polonsky (1994) demonstrated that green marketing is generally a broad concept which can be applied to consuming commodities, industrial goods and/or even services. Once the green products with its special attributes are distinguished to be able to bring customer benefits, increasing the inherent customers value, marketing attention is drawn to this consumer value and leads to the fact that green marketing strategies should be successful and effective (Ottman et al., 2006). In recent years, people prefer to purchase green products which are generated to shrink environment damages. When society has been paying more and more attention on the natural environment, green promotion activities are of the special public interests companies have to alter their marketing strategies attempting the above society’s concerns (Davari & Strutton, 2014; Polonsky, 1994; Vandermerwe & Oliff, 1990). A growing body of literature has focused on green marketing, and previous literature mainly concentrated on the relationship between psychological brand benefits and environmental concern (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, 2012), green marketing and corporate image (Ko et al., 2013), green advertising between brand attitude and environmental concern (Matthes et al., 2014). However, there is still a lack of research on “carbon offset” or “carbon neutrality”, two aspects of green promotion, which might affect the influences of customer value on brand equity. Carbon offset provides opportunities to individuals and institutions that can make direct donations to help reducing emissions elsewhere. Since they are concerned with their emissions of carbon dioxide which had changed the environment and climate dramatically (Kotchen, 2009). “Carbon offset” and “carbon neutrality” are both researched for revising the policy and trading (Kollmuss et al., 2008). However, Larceneux et al. (2012) examined the moderating effect of the brand on organic label effects, the result showed that brand equity is associated positively with organic label, in spite of the brand equity level; an organic label makes the impression to the customer that it’s the environmentally friendly attribute salient, which has definitely a positive impact on perceived quality. By extension, thus, this study proposes that when customers recognize the brand having high green promotion (including high carbon offset and high carbon neutrality), and that brand has high perceived value to customers, it will enhance customers’ perceived value on brand equity. So, when customer perceived higher degree of green promotion (including carbon offset and carbon neutrality) perceived value toward the brand equity should be higher.

Rashid (2009) stated that the higher the awareness of eco-label the stronger the relationship between attitude toward environmental protection and intention to purchase a product with environmental friendly features. In other words, customers who have higher environmental awareness will have higher perceived value on the brand of the green product. By extension, thus, this study states that customers who have high green marketing awareness tend to focus on higher level of customer value, so when the customers’ green marketing awareness is high, they will have higher perceived value toward the brand equity. Specifically, the following hypotheses are developed:

H3a: High green promotion (including high carbon offset and high carbon neutrality) customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity.

H3b: High green marketing awareness customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity.

The Moderating Effect of Green Brand Loyalty

This study proposes that green brand loyalty will moderate the effects of customer values on brand equity. Brand loyalty is the core attribute of brand equity (McIntosh, 1991). The brand influences customer repeated purchase including behavioral, or purchase, loyalty, whereas attitudinal brand loyalty includes a degree of positional commitment, according to some unique value relate to the brand. In addition, the customer trusts the brands high and affects are related by both attitudinal and purchase loyalty, it contributes to greater market share and premium prices in the marketplace (Aaker, 1996; Oliver, 1999). So it can be seen that how important of brand loyalty on brand equity. Ha (2009) addressed that brand loyalty was a key moderators to facilitate the relationship between brand equity and service quality. However, there is a lack of research on studying in green market. Based on Chen (2010) s’ framework, green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust impact positively on green brand equity. Thus, this study proposes that when customers have high green brand loyalty in that brand, and that brand has high perceived value to customers, it will enhance customers’ perceived value on brand equity. Consumers who have high green brand loyalty tend to focus on higher level of customer value, so when the customers’ green brand loyalty is high, they will have higher perceived value toward the brand equity. Consequently, it is hypothesized that:

H4: High green brand loyalty customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity.

The Moderating Effect of Self-Expressive Benefit

This study proposes self-expressive benefit as psychological moderator, which will moderate the relationship between brand equity and purchase intention. The brand personality can provide a link to the brands emotional and self-expressive benefit, and furthermore, brand personality is one part of brand equity (Aaker, 1996). Since brand equity influence consumers brand preference and purchase intentions. Chen & Chang (2008), so there are the links among those variable shown follow as, self-expressive benefit→ brand personality; brand personality→ brand equity, brand equity→ purchase intention. In addition, consumers tend to focus on both brand credibility and brand prestige when they purchase high self-expressive products (Baek et al., 2010). Thus, this study addresses that when customers have high self-expressive benefit with a brand and that brand has high equity, it will enhance their intention to buy that brand. Consumers who have high self-expressive benefit tend to focus on higher level of brand equity, so when the brand equity is high, they will have higher purchase intention toward the brand. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: High self-expressive benefit customers will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention, word-of-mouth intention).

The Moderating Effect of Brand Social Responsibility

This study addresses brand social responsibility as relational moderator, which will moderate the relationship between brand equity and purchase intention. Yan (2003) identified CSR marks the difference between the brands that have captured the imagination of tomorrow’s consumers and those that are proving to be casualties. Moreover, a company’s CSR efforts can affect consumers’ intentions to purchase it products (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). Blumenthal & Bergstrom (2003) founded that polymerization of both ‘branding’ and ‘corporate social responsibility (CSR)’ is a driver for firms to firm brand management. Based on previous literatures above, those approved the correlations among brand equity, CSR, brand social responsibility, and purchase intention, so there are the links among those variable shown follow as, brand social responsibility→ corporate social responsibility; branding & corporate social responsibility→ brand equity; brand equity→ purchase intention. Consequently, this study proposes that when customers recognize the brand having high brand social responsibility, as well as, that brand has high equity, it will enhance their intention to buy that brand. Consumers who identify high brand social responsibility tend to focus on higher level of brand equity, so when the brand equity is high, they will have higher purchase intention toward the brand. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H6: High brand social responsibility customers will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention, word-of-mouth intention).

Research Design and Methodology

The Conception Model and Hypotheses

From the above Hypothesis development presented in section II, the conceptual model of the research is consolidated in Figure 1 below:

Constructs Measurement and Questionnaire Design

For the purpose of the examining the hypotheses, the study formulates eight major constructs, which are (1) customer values; (2) brand equity; (3) customer behavioral intentions; (4) green marketing; (5) green brand loyalty; (6) psychological moderator; (7) relational moderator, and (8) demographic moderators. The measurement scales of constructs were developed in accordance with the definitions and concept provided within this study. The detail of measurements formulation is presented below in the Table 2.

| Table 2 Summary of Questionnaire Development | |||

| S. No | Variables | Sources of Questions | Number of questions |

| 1. | Customer Value | ||

| Green brand image | Chen (2009) | 5 | |

| Green perceived quality | Anselmsson et al. (2014) | 3 | |

| Altruistic value | Albayrak et al. (2013) | 3 | |

| Relationship quality | Garbarino et al. (1999); Hennig-Thurau et al. (1997) | 8 | |

| Price premium | Anselmsson et al. (2014) | 3 | |

| 2. | Brand Equity | Ha (2009); Sheng & Teo (2012) | 8 |

| 3. | Customer behavioral intentions | ||

| Purchase intention | Ko et al. (2013) | 3 | |

| Word of mouth intention | Ko et al. (2013); Kim et al. (2001) | 3 | |

| 4. | Green marketing | ||

| Green promotion | Davari & Strutton (2014) | 5 | |

| Green marketing awareness | Ko et al. (2013) | 5 | |

| 5. | Green brand loyalty | Ko et al. (2013); Kim et al. (2001) | 6 |

| 6. | Self-expressive Benefit | Kim et al. (2001); Anselmsson et al. (2014) | 6 |

| 7. | Brand social responsibility | Anselmsson et al. (2014) | 4 |

Sampling Plan and Sample Characteristics

At the beginning of the questionnaire survey includes six green tissue brands. The respondents were asked to pick up only one of six green tissue brands, and to answer our questionnaire referring to their experience about green marketing and green consuming of the tissue brand that they have chosen. All the six green tissue brands’ name and logo image (including Kleenex, Dandelion, Bai-Hua, Andante, Flower language and Bai Ji Pai) were presented on the questionnaire survey to the respondents who have previous purchasing green products experience on at least one of the six tissue brands above. Two hundred fifty (250) respondents filled in the questionnaire, based on their experiences of purchasing tissue brand. However, 14 answers were invalid. Therefore, only 236 valid questionnaires are used for further analysis. The number of samples in each brand of the questionnaire for respondents is shown in Table 3, and the characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 4.

| Table 3 Numbers of Sample in Each Brand | |||

| Items | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Please specify which brand below that you purchased most often before. (Please ONLY pick one brand) | Kleenex | 159 | 67% |

| Dandelion | 5 | 2% | |

| Bai-Hua | 7 | 3% | |

| Andante | 57 | 24% | |

| Flower language | 4 | 2% | |

| Bai Ji Pai | 4 | 2% | |

| Table 4 Characteristics of the Respondents | |||

| Items | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 108 | 46% |

| Female | 128 | 54% | |

| Age | Under 25 | 113 | 47.9% |

| 25 to 34 Years Old | 87 | 36.9% | |

| 35 to 49 Years Old | 31 | 13.1% | |

| 50 to 54 Years Old | 3 | 1.3% | |

| 55 to 64 Years Old | 1 | 0.4% | |

| More than 65 Years Old | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Education | High school or less | 11 | 4.7% |

| College | 27 | 11.4% | |

| University | 176 | 74.6% | |

| Master | 21 | 8.9% | |

| Doctorate | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Monthly Disposable Income (NTD) | Less than $10,000 | 97 | 41% |

| $10,001-$20,000 | 34 | 15% | |

| $20,001-$30,000 | 61 | 26% | |

| $30,001-$40,000 | 22 | 9% | |

| $40,001-$50,000 | 10 | 4% | |

| More than $20,000 | 12 | 5% | |

| Occupation (or Sectors Belonged) | Primary Industry | 8 | 3.4% |

| Public Sector | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Information Sector | 5 | 2.1% | |

| High-Tech Industry | 9 | 3.8% | |

| Financial Industry | 4 | 1.7% | |

| Service Sector | 47 | 19.9% | |

| Communication Industry | 5 | 2.1% | |

| Self-employed | 33 | 14% | |

| Housekeeper | 7 | 3% | |

| Student | 106 | 44.9% | |

| Other | 8 | 3.4% | |

Results and Discussion

Reliability of the Research Constructs

To verify the dimensionality and reliability of the constructs, purifications, including factor analysis, correlation analysis, and coefficient alpha analysis were conducted in this study. According to Hair et al., (2011), to achieve reliability of the construct, factor loading should be higher than 0.6, item-to-total correlation should be higher than 0.5, and all Cronbach’s alpha coefficient should be higher than 0.7. The result as shown in Table 5 suggested that all factor loadings are ranged between 0.661 to 0.960, which have achieved the criteria of 0.6. All item-to-total correlations are ranged between 0.532 to 0.908, which are higher than the criteria of 0.5. All Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are ranged 0.828 to 0.960, which are higher than criteria of 0.7.

| Table 5 Reliability of the Research Constructs | ||||

| Constructs / Factors | No. of Items | Factor Loading | Item to total Correlation | Cronbach Alpha |

| Green Brand Image | 5 | 0.849-0.916 | 0.770-0.863 | 0.936 |

| Green Perceived Quality | 3 | 0.932-0.952 | 0.848-0.889 | 0.937 |

| Altruistic Value | 3 | 0.920-0.955 | 0.823-0.893 | 0.926 |

| Relationship Quality | 8 | 0.818-0.912 | 0.770-0.878 | 0.957 |

| Price Premium | 3 | 0.751-0.937 | 0.532-0.818 | 0.828 |

| Brand Equity | 8 | 0.661-0.881 | 0.585-0.829 | 0.927 |

| Purchase Intention | 3 | 0.906-0.921 | 0.791-0.819 | 0.904 |

| Word-of-mouth Intention | 3 | 0.945-0.960 | 0.877-0.908 | 0.947 |

| Green Promotion | 5 | 0.890-0.922 | 0.830-0.872 | 0.944 |

| Green Marketing Awareness | 5 | 0.845-0.903 | 0.760-0.841 | 0.926 |

| Green Brand Loyalty | 6 | 0.703-0.910 | 0.606-0.846 | 0.920 |

| Self-expressive Benefit | 6 | 0.878-0.930 | 0.826-0.898 | 0.960 |

| Brand Social Responsibility | 4 | 0.873-0.930 | 0.778-0.870 | 0.924 |

The Relationship between Customer Values, Brand Equity, and Behavioral Intention

Hypothesis 1 proposes that customer values, which consist of green brand image, green perceived quality, altruistic value, relationship quality and price premium, have positive influences on brand equity. Therefore, Table 6 presents the results of the regressions analyses for customer value as an independent variable and brand equity as dependent variable. However, 2 of 5 factors of customer values are significant, one is green perceived quality, it has significantly positive effect toward brand equity (β=0.157, R2=0.681, p=0.000); the other is relationship quality, which also has significantly positive effect toward brand equity (β=0.445, R2=0.681, p=0.000). Another 2 of 5 factors, namely price premium (β=0.094, p<0.1), and green brand image (β=0.128, p<0.1) have marginally influence on brand equity. These results support the studies of Zeithaml (1988), Aaker (1991), and Garretson & Clow (1999). They explained that perceived quality has positive effect on customer’s mind to brand equity. In addition, it also supports the studies of Aaker (1996), Hennig?Thurau & Klee (1997), and Sweeney & Soutar (2001). In this study, altruistic value does not show a significant influence on brand equity (β=0.094, p>0.1). They explained that relationship quality has positive impact on customer’s mind to brand equity. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is partially supported.

| Table 6 Regression Analyses for Customer Value and Brand Equity | |

| Independent Factors-“Customer Value” | Dependent Factors-“Brand Equity” |

| Model 1 | |

| Beta (β) | |

| Altruistic Value (CVav) | 0.094 |

| Price Premium (CVpp) | 0.094+ |

| Green Brand Image (CVgbi) | 0.128+ |

| Green Perceived Quality (CVgpq) | 0.157* |

| Relationship Quality (CVrq) | 0.445*** |

| R2 | 0.681 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.674 |

| Model F-value | 98.223 |

| Model p-value | 0.000 |

| VIF | 2.215 - 3.766 |

| D-W | 1.899 |

Hypothesis 2 proposes that brand equity has positive influences on customer’s purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention. Table 7 presents and suggests that brand equity has significantly positive effect toward purchase intention (β=0.754, R2=0.568, p=0.000), moreover, brand equity also has significantly positive effect toward word-of-mouth intention (β=0.763, R2=0.582, p=0.000). These results support the study of Yoshida & Gordon (2012), who explained that brand equity has positive effect on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention). Hence, Hypotheses 2 is supported.

| Table 7 Regression Analyses for Brand Equity and Customer Behavioral Intentions | ||

| Independent Factors- “Brand Equity” | Dependent Factors- “Customer Behavioral Intentions” | |

| Purchase Intention | Word-of-Mouth Intention | |

| Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Beta (β) | Beta (β) | |

| Brand equity (BE) | 0.754*** | 0.763*** |

| R2 | 0.568 | 0.582 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.566 | 0.580 |

| Model F-value | 307.758 | 325.292 |

| Model p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| VIF | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| D-W | 1.751 | 1.822 |

The Moderating Effects of Green Marketing

Hypothesis 3a addresses that customers perceiving a high green promotion (consisting of high carbon offset and high carbon neutrality) customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity. Still, hypothesis 3b proposes that customer perceiving high green marketing awareness customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity.

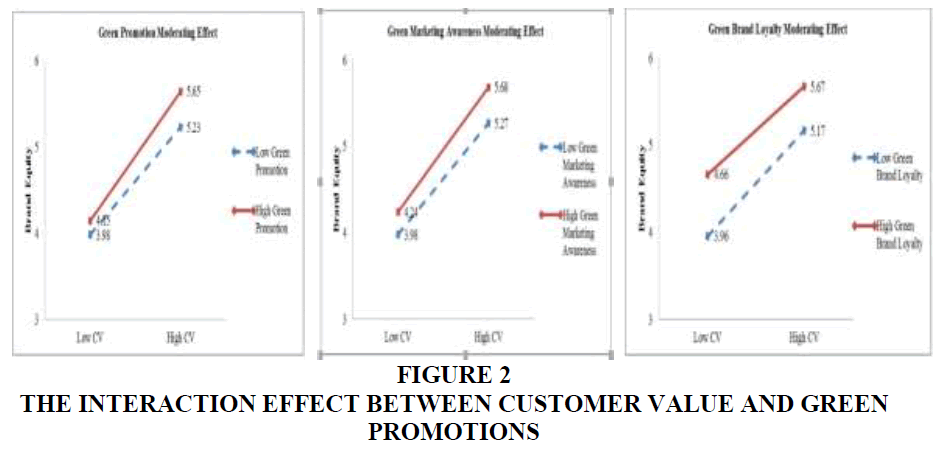

The result of ANOVA is shown in Table 8 and Figure 2. Taking customer value as an independent variable, brand equity as a dependent variable and green promotion as a moderating variable. It indicates that individuals with higher green promotion concept (having high carbon offset and high carbon neutrality) will lead to have higher customer value which will have positive influences on brand equity (F=71.675, p=0.000). Figure 2 shows that under high customer value, consumers have more positive attitude toward the brand equity, when consumers have high green promotion concept (5.6474) than low green promotion concept (5.2300).

| Table 8 Results of Cluster and ANOVA for Green Promotion | ||||||

| Name of Factor | Low Customer Value | High Customer Value | F-Value (p) | Duncan | ||

| 1. Low GP(n=99) | 2. High GP(n=45) | 3. Low GP(n=25) | 4. High GP(n=67) | |||

| Brand Equity | 3.9836 | 4.1472 | 5.2300 | 5.6474 | 71.675 (0.000) | (12,3,4) |

| Brand Equity | 3.9790 | 4.2379 | 5.2652 | 5.6843 | 73.120 (0.000) | (12,3,4) |

| Brand Equity | 3.9561 | 4.6641 | 5.1650 | 5.6716 | 80.440(0.000) | (1,2,3,4) |

These results are supported by Larceneux et al. (2012). They explained that moderating effect of the brand on organic label an effect, which has definitely a positive impact on perceived quality. However, the result also supports the previous studies that people might pay more attention to green promotional movements, when they favor to purchase green products with high environment concerns (Davari & Strutton, 2014; Polonsky, 1994; Vandermerwe & Oliff, 1990). Therefore, hypotheses 3a is supported.

Table 8 also shows that taking customer value as an independent variable, brand equity as a dependent variable and green marketing awareness as a moderating variable, it indicates that individuals with higher green marketing awareness will result in have higher customer value which will have positive influences on brand equity (F=73.120, p=0.000). Figure 2 shows that under high customer value, consumers have more positive attitude toward the brand equity, when consumers have high green marketing awareness (5.6843) than low green marketing awareness (5.2652). These results are supported by Rashid (2009), who stated that the higher the awareness of eco-label the stronger the relationship between attitude toward environmental protection and intention to purchase a product with environmental friendly features. In other words, customers who have higher environmental awareness, they will have higher perceived value on the brand of the green product. In summary, a hypothesis 3b is supported.

Hypothesis 4 addresses that high green brand loyalty customers will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity. The result of ANOVA is shown in Table 8, for customer value as an independent variable, brand equity as a dependent variable and green brand loyalty as a moderating variable. Based on the result shown below in Table 8, it shows that individuals with higher green brand loyalty will lead to have higher customer value which will have positive influences on brand equity (F=80.440, p=0.000). Then, for Duncan value in Table 8, it shows that 1, 2, 3 and 4 are different to each other. Figure 2 shows that under high customer value, consumers have more positive attitude toward the brand equity, when consumers have high green brand loyalty (5.6716) than low green brand loyalty (5.1650). These results are supported by Chen (2010). It asserted that green trust is positively related to green brand equity. In other words, the customers with higher green brand loyalty will result in higher perceived value on the brand. In conclusion, a hypothesis 4 is supported.

The Moderating effects of Self-Expressive Benefit (Psychological Moderator)

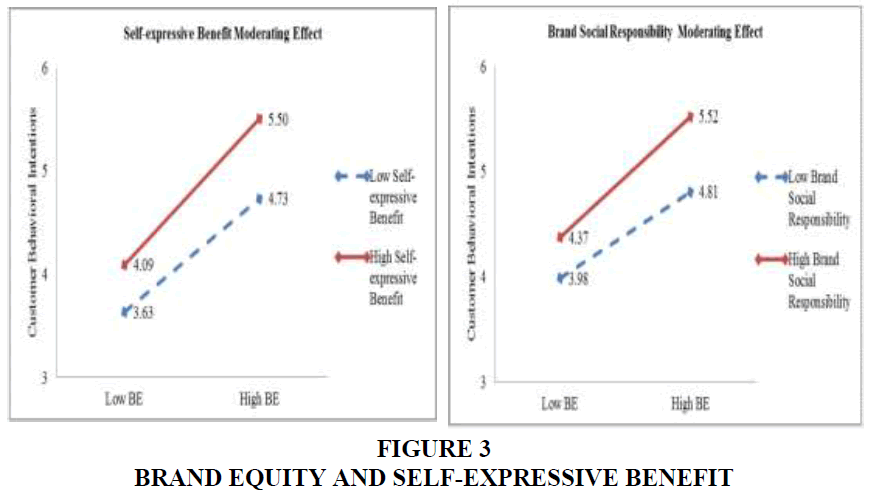

Hypothesis 5 proposes that high self-expressive benefit customers will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention). The result of ANOVA is shown in Table 9; it shows that for brand equity as an independent variable, customer behavioral intentions as a dependent variable, and self-expressive benefit as a moderating variable. The result presents that individuals with higher self-expressive benefit will result in have higher brand equity which will have positive influences on customer behavioral intentions (F=73.112, p=0.000). Then, for Duncan value in Table 9, it shows that 1, 2, 3 and 4 are different to each other. Figure 3 shows that under high brand equity, consumers have more positive attitude toward customer behavioral intentions, when consumers have high self-expressive benefit (5.5020) than low self-expressive benefit (4.7333). These results are supported by Baek et al. (2010). They explained that high self-expressive benefit customers will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions. Hence, a hypothesis 5 is supported.

| Table 9 Results of Cluster and ANOVA for Self-Expressive Benefit | ||||||

| Name of Factor | Low Brand Equity | High Brand Equity | F-Value (p) | Duncan | ||

| 1. Low SEB (n=79) | 2. High SEB(n=35) | 3. Low SEB(n=40) | 4. High SEB(n=82) | |||

| 3.6308 | 4.0905 | 4.7333 | 5.5020 | 73.112 (0.000) | (1,2,3,4) | |

| 3.9841 | 4.3719 | 4.8062 | 5.5228 | 67.436 (0.000) | (1,2,3,4) | |

Hypothesis 6 addresses that high brand social responsibility customers will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention). The result of ANOVA is shown in Table 9; it shows that for brand equity as an independent variable and customer behavioral intentions as a dependent variable, and brand social responsibility as a moderating variable. Based on the result shows that individuals with higher brand social responsibility will lead to have higher brand equity which will have positive influences on customer behavioral intentions (F=67.435, p=0.000). Then, for Duncan value in Table 9, it shows that 1, 2, 3 and 4 are different to each other. Figure 3 shows that under high brand equity, consumers have more positive attitude toward customer behavioral intentions, when consumers have high brand social responsibility (5.5228) than low brand social responsibility (4.8062). These results are supported by Sen & Bhattacharya (2001). They asserted that a company’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) efforts can affect consumers’ intentions to purchase it products. Still, Blumenthal & Bergstrom (2003) founded that both ‘branding’ and ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)’ is polymerization to brand management. In other words, consumers who identify high brand social responsibility tend to focus on higher level of brand equity, so when the brand equity is high, they will have higher purchase intention toward the brand. Therefore, a hypothesis 6 is supported.

Conclusion and Suggestions

Research Conclusions

The major objectives of this study are to empirically investigate: (1) the relationship between green customer values, green brand equity, and customer behavioral intentions, (2) the moderating effects of green marketing and green brand loyalty on the relationship between customer value and brand equity, (3) the moderating effects of self-expressive benefit, brand social responsibility on the relationship between brand equity and customer behavioral intentions.

Several conclusions could be drawn from the results of this study. First, Individuals having higher value of green perceived quality and relationship quality will have positive impact on brand equity (Aaker, 1991; Garretson & Clow, 1999; Hennig?Thurau & Klee, 1997; Sweeney & Soutar, 2001). Second, brand equity influence consumer’s brand preference and purchase intentions (Chen & Chang, 2008; Moradi & Zarei, 2011). These results also are in agreement with the results of previous studies indicating that green brand equity has positive impact on behavioral intentions.

Third, customers perceiving higher green promotion (including higher carbon offset and higher carbon neutrality) will strengthen the positive effect of customer value on brand equity. This result is in line with Larceneux et al. (2012), which examined the moderating effect of the brand on organic label effects. These results are supported that people who prefer to purchase green products with high environment concerns tend to pay more attention to green promotional activities (Davari & Strutton, 2014). In addition, the study results also indicate that customers who have higher green marketing awareness tend to focus on higher level of customer value, so when the customers’ green marketing awareness is high, they will have higher perceived value toward the brand equity.

Fourth, the results are also supported by Rashid (2009) green trust are positively related to green brand equity, which further confirm that consumers who have higher green brand loyalty tend to focus on higher level of customer value, so when the customers’ green brand loyalty is high, they will have higher perceived value toward the brand equity. Fifth, these results confirmed the study result of Chen (2010) that consumers who have higher self-expressive benefit tend to focus on higher level of brand equity, so when the brand equity is high, they will have higher purchase intention toward the brand (Baek et al., 2010).

Sixth, consumers who identify high brand social responsibility tend to focus on higher level of brand equity, so when the brand equity is high, they will have higher purchase intention toward the brand. This result is also supported by the study of Sen & Bhattacharya (2001), which indicated that a company’s CSR efforts can affect consumers’ intentions to purchase. Blumenthal & Bergstrom (2003) founded that the polymerization of both ‘branding’ and ‘CSR’ is a key to brand management.

Managerial Implications

Several managerial implications can be inferred from the conclusions of this research. First, customers perceiving higher values do really help company’s brand in customers’ impression. Green promotion and green brand loyalty will enhance customer values on company’s brand. Therefore, companies could think over how to increase green perceived quality and relationship quality of customer values. Furthermore, how to run green promotions and build-up green brand loyalty to enrich customer values, which further strengthen brand in customers’ mind, become the important tasks for firms to grow.

In addition, customers who have higher self-expressive benefit will strengthen the positive effect of brand equity on customer behavioral intentions. Still, customers who identify higher brand social responsibility tend to focus on higher level of brand equity. So when the brand equity is higher, customers will have higher purchase intention toward the brand. Hence, company also could take into account that how to improve customers’ self-expressive benefit, as well as, to enrich company’s brand social responsibility to customers, those movements will enhance brand equity in customers’ mind, and then to influence positively customer behavioral intentions (purchase intention and word-of-mouth intention).

Future Research Directions

Even though the results demonstrated in this study provide a new perception into the antecedents, moderators, and consequences of brand equity for green marketing, the findings maybe confounded by the following issues which merit for further investigation.

Firstly, the limitation could be caused by the respondents. Those respondents of this study are conveniently investigated from e-mail invitation, web-based and paper-based questionnaire survey via the Internet link to the questionnaire, such as LINE Messenger. Those clusters could have quite high similarities, in terms of culture, environment, etc. Although according to Calder et al. (1981) the validity and reliability of the results might be affected by a few limitations as follow: The used of indigenous samples are acceptable if the study required highly internal validity, especially during theoretical development. Even though, convenience sampling is appropriate for this study; we cannot refute the fact that 236 respondents are insufficient to represent the whole population. Because of that, a larger sample and further research are needed.

Besides, altruistic value is not significantly influence on brand equity in this study. Those factors may subject for further validation. Moreover, future research can also add more moderating variables in the research framework, for example, characteristics of consumers, consumers’ life style, product involvement, personal demographic variables etc.

References

- Aaker, D.A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

- Aaker, D.A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38(3), 102-120.

- Ailawadi, K.L., Lehmann, D.R., & Neslin, S.A. (2003). Revenue premium as an outcome measure of brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 1-17.

- Albayrak, T., Aksoy, ?., & Caber, M. (2013). The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(1), 27-39.

- Anselmsson, J., Bondesson, N.V., & Johansson, U. (2014). Brand image and customers’ willingness to pay a price premium for food brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(2), 90-102.

- Baek, T.H., Kim, J., & Yu, J.H. (2010). The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychology & Marketing, 27(7), 662-678.

- Bello, D.C., & Holbrook, M.B. (1995). Does an absence of brand equity generalize across product classes? Journal of Business Research, 34(2), 125-131.

- Blumenthal, D., & Bergstrom, A. (2003). Brand councils that care: Towards the convergence of branding and corporate social responsibility. The Journal of Brand Management, 10(4), 327-341.

- Calder, B.J., Philipss, L.W., & Tybout, A.M. (1981). Designing resarch for applicaion. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(2), 197-207.

- Chang, P.L., & Chieng, M.H. (2006). Building consumer-brand relationship: A cross?cultural experiential view. Psychology & Marketing, 23(11), 927-959.

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M.B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81-93.

- Chen, C.F., & Chang, Y.Y. (2008). Airline brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intentions-The moderating effects of switching costs. Journal of Air Transport Management, 14(1), 40-42.

- Chen, Y.S. (2008a). The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(3), 271-286.

- Chen, Y.S. (2008b). The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(3), 531-543.

- Chen, Y.S. (2010). The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 307-319.

- Chi, H.K., Yeh, H.R., & Yang, Y. (2009). The impact of brand awareness on consumer purchase intention: The mediating effect of perceived quality and brand loyalty. Journal of International Management Studies, 4(1), 135-144.

- Choi, Y.G., Ok, C., & Hyun, S.S. (2011). Evaluating relationships among brand experience, brand personality, brand prestige, brand relationship quality, and brand loyalty: An empirical study of coffeehouse brands. Paper presented at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA.

- Cronin Jr, J.J., Brady, M.K., & Hult, G.T.M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193-218.

- Davari, A., & Strutton, D. (2014). Marketing mix strategies for closing the gap between green consumers' pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 0(0), 1-24.

- Davis, R., Buchanan-Oliver, M., & Brodie, R.J. (2000). Retail service branding in electronic-commerce environments. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 178-186.

- De Matos, C.A., & Rossi, C.A.V. (2008). Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 578-596.

- Dobni, D., & Zinkhan, G.M. (1990). In search of brand image: A foundation analysis. Advances in Consumer Research, 17(1), 110-119.

- Faircloth, J.B., Capella, L.M., & Alford, B.L. (2001). The effect of brand attitude and brand image on brand equity. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(3), 61-75.

- Farquhar, P.H. (1989). Managing brand equity. Marketing Research, 1(3), 24-33.

- Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M.S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70-87.

- Garretson, J.A., & Clow, K.E. (1999). The influence of coupon face value on service quality expectations, risk perceptions and purchase intentions in the dental industry. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(1), 59-72.

- Granzin, K.L., & Olsen, J.E. (1991). Characterizing participants in activities protecting the environment: A focus on donating, recycling, and conservation behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 1-27.

- Ha, H.Y. (2009). Effects of two types of service quality on brand equity in China: The moderating roles of satisfaction, brand associations, and brand loyalty. Seoul Journal of Business, 15(2), 59-83.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

- Haltiwanger, J., & Waldman, M. (1993). The role of altruism in economic interaction. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 21(1), 1-15.

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1254-1263.

- Hennig?Thurau, T., & Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: A critical reassessment and model development. Psychology & Marketing, 14(8), 737-764.

- Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E., & Schlesinger, L.A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164-174.

- Hoeffler, S., & Keller, K.L. (2002). Building brand equity through corporate societal marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(1), 78-89.

- Hopper, J.R., & Nielsen, J.M. (1991). Recycling as altruistic behavior normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environment and Behavior, 23(2), 195-220.

- Jackson, A.L., Olsen, J.E., Granzin, K.L., & Burns, A.C. (1993). An investigation of determinants of recycling consumer behavior. Advances in Consumer Research, 20(1), 481-487.

- Keller, K.L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. The Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22.

- Ko, E., Hwang, Y.K., & Kim, E.Y. (2013). Green marketing'functions in building corporate image in the retail setting. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1709-1715.

- Kollmuss, A., Zink, H., & Polycarp, C. (2008). Making sense of the voluntary carbon market: A comparison of carbon offset standards. Paper presented at the Stockholm Environment Institute and Tricorona.

- Kotchen, M.J. (2009). Voluntary provision of public goods for bads: A theory of environmental offsets. The Economic Journal, 119(537), 883-899.

- Larceneux, F., Benoit-Moreau, F., & Renaudin, V. (2012). Why might organic labels fail to influence consumer choices? Marginal labelling and brand equity effects. Journal of Consumer Policy, 35(1), 85-104.

- Lee, C., & Wang, Y. (2009). A study on ecological purchasing behavior of green products: The case of college students in Taiwan and Mainland China. Journal of Advanced Engineering, 7(3), 125-134.

- Lee, J.S., & Back, K.J. (2010). Reexamination of attendee-based brand equity. Tourism Management, 31(3), 395-401.

- Matthes, J., Wonneberger, A., & Schmuck, D. (2014). Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1885-1893.

- McIntosh, A. (1991). The impact of environmental-Issues on marketing and politics in the 1990s. Journal of the Market Research Society, 33(3), 205-217.

- Moradi, H., & Zarei, A. (2011). The impact of brand equity on purchase intention and brand preference-The moderating effects of country of origin image. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 5(3), 539-545.

- Mudambi, S.M., Doyle, P., & Wong, V. (1997). An exploration of branding in industrial markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(5), 433-446.

- Nan, X., & Heo, K. (2007). Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 63-74.

- O’cass, A., & Frost, H. (2002). Status brands: Examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2), 67-88.

- Oh, H. (2000). The effect of brand class, brand awareness, and price on customer value and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24(2), 136-162.

- Oliver, R.L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 33-44.

- Oskamp, S., Harrington, M.J., Edwards, T.C., Sherwood, D.L., Okuda, S.M., & Swanson, D.C. (1991). Factors influencing household recycling behavior. Environment and Behavior, 23(4), 494-519.

- Ottman, J.A. (2011). The new rules of green marketing. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Ottman, J.A. (2008). The five simple rules of green marketing. Design Management Review, 19(4), 65-69.

- Ottman, J.A., Stafford, E.R., & Hartman, C.L. (2006). Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 48(5), 22-36.

- Park, C.S., & Srinivasan, V. (1994). A survey-based method for measuring and understanding brand equity and its extendibility. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 31(2), 279- 296.

- Park, C.W., Jaworski, B.J., & MacInnis, D.J. (1986). Strategic brand concept-image management. Journal of Marketing, 50(4), 135-145.

- Polonsky, M.J. (1994). An introduction to green marketing. Electronic Green Journal, 1(2), 1-10.

- Rashid, N.R.N.A. (2009). Awareness of eco-label in Malaysia’s green marketing initiative. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(8), p132-141.

- Richardson, P.S., Dick, A.S., & Jain, A.K. (1994). Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 28-36.

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C.B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225-243.

- Sheng, M.L., & Teo, T.S. (2012). Product attributes and brand equity in the mobile domain: The mediating role of customer experience. International Journal of Information Management, 32(2), 139-146.

- Shirazi, A., & Karimi Mazidi, A. (2013). Investigating the effects of brand identity on customer loyalty from social identity perspective. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 6(2), 153-178.

- Smith, A., Stancu, C., & Authority, C. (2006). Eco-labels: A short guide for New Zealand producers. Retrieved from www.landcareresearch.co.nz

- Smith, M.D., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2001). Consumer decision?making at an Internet shopbot: Brand still matters. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 49(4), 541-558.

- Sriram, S., Balachander, S., & Kalwani, M.U. (2007). Monitoring the dynamics of brand equity using store-level data. Journal of Marketing, 71(2), 61-78.

- Sweeney, J.C., & Soutar, G.N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 203-220.

- Vandermerwe, S., & Oliff, M.D. (1990). Customers drive corporations. Long Range Planning, 23(6), 10-16.

- Yan, J. (2003). Corporate responsibility and the brands of tomorrow. The Journal of Brand Management, 10(4), 290-302.

- Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2001). Developing and validating multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of Business Research, 52(1), 1-14.

- Yoshida, M., & Gordon, B. (2012). Who is more influenced by customer equity drivers? A moderator analysis in a professional soccer context. Sport Management Review, 15(4), 389-403.

- Zeithaml, V.A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. The Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2-22.

- Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. The Journal of Marketing, 60(0), 31-46.