Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on The Relationship Between Personality Traits and Premature Sign-off

Mohannad Obeid, University Malaysia Terengganu

Zalailah Salleh, University Malaysia Terengganu

Mohd Nazli Mohd Nor, University Malaysia Terengganu

Keywords

conscientiousness, neuroticism, job satisfaction, premature sign-off, internal auditors.

Introduction

Studies in the internal audit literature show that audit quality can be negatively affected by dysfunctional audit behaviors. However, due to the increasing significance of the functions of an internal audit and the scarce archival evidence on the quality of internal audits (Abbott et al., 2016), this study uses a substitute technique to capture the dimensions of audit quality. This will enable researchers to ask auditors questions about the undertaking of quality reducing acts, such as dysfunctional audit behaviors, as recommended by Svanström (2016). Further, according to O'Leary and Stewart (2007), despite the critical importance of ethics in the internal audit function, little was published in this area.

Studies on internal audits show that audit quality can be negatively affected by dysfunctional audit behaviors, especially premature sign-off, which is considered the top dysfunctional audit behavior by internal auditors (Ling & Akers, 2010). Premature audit sign-offs directly affect audit quality and violate professional standards (Shapeero et al., 2003). Prior studies suggest that factors, such as job dissatisfaction, are antecedents for deviant behaviors (e. g. Tuna et al., 2016). Homans (1961) explained the relationship in light of the Social Exchange theory, saying that employees that have a high level of job dissatisfaction may have a tendency to get involved in deviant behaviors. Such deviant behavior can also be explained by dissatisfied employees who are not concerned about losing their jobs. In contrast, employees with a high level of job satisfaction are more likely to behave in a positive and constructive manner towards their work and their organisation (Bayarçelik & Findikli, 2016).

There are numerous studies that have looked at job satisfaction, but limited research exists on the predictors of job satisfaction. According to Sun et al. (2016), worker job satisfaction was studied in over 85 peer-reviewed meta-analysis studies. In order to improve job satisfaction, Hodge (2012) proposed that it is critical to identify and understand the factors that contribute to job dissatisfaction for internal audit employees so that they can be appropriately addressed. Previous research has identified a relationship between particular personality traits and the level of job satisfaction (Ayan & Kocacik, 2010; Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002; Schneider & Dachler, 1978; Spector, 1997). One research proposed that certain personalities or disposition is associated with job satisfaction, regardless of the type or nature of the work or the environment (Jex and Britt, 2014). In other words, some employees may be genetically predisposed to be positive or negative about their job. Spector (1997) stated that “Although many traits were shown to correlate significantly with job satisfaction, most research with personality has done little more than demonstrate relations without offering much theoretical explanation” (p. 51).

Numerous personality traits were tested in relation to job satisfaction. However, “There is confusion regarding which person variables should be examined. A formidable array of person variables was discussed as possible determinants of job satisfaction in the research literature” (Arvey et al., 1991; p. 377). In this study, the effects of particular personality traits on employee satisfaction and attitudes were conducted gradually, rather than all at once. Among the personality traits, neuroticism (e.g., Tanoff, 1999) and conscientiousness (e.g., Salgado, 1997; Judge et al., 1999) are major predictors of job satisfaction.

Therefore, this study aims to examine the possible effect of job satisfaction and personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) on premature sign-off. It is expected that job satisfaction will yield a mediating relationship between conscientiousness, neuroticism, and premature sign-off. In this study, we look at behavior as a result of situational and dispositional antecedents, which is similar to the interactions perspective (Diener et al., 1984; Endler & Edwards, 1985, 1986). Several studies have looked at the effect of individual differences on dysfunctional audit behavior (Mohd Nor, 2001); however, this study will integrate the effects of both individual personality traits and the level of job satisfaction on dysfunctional audit behaviors. Several researchers have proposed that a better understanding of individual personality differences and work performance and satisfaction will be important for employee selection (Barrick, Mount, & Judge, 2001; Ilies et al., 2009; Mount, Ilies, & Johnson, 2006). Further research needs to be conducted to identify the links between job satisfaction and personality (disposition), context (situation), and behavior (Judge & Zapata, 2015). Thus, for the purposes of this study, a theoretical model was developed that takes into consideration specific personality traits that can directly or indirectly affect dysfunctional audit behaviors, such as premature sign-off.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Personality Traits, Job Satisfaction and Premature Sign-off

Personality is one of the individual disposition factors. Personality can be described as the individual pattern of psychological processes arising from individual characteristics. Different individuals have different emotions, behaviors, feelings, and patterns of thought (Thomas & Segal, 2006) and, hence, different personalities. Individuals possess a unique and dynamic set of characteristics that uniquely influences his or her motivations, cognitions, and behaviors in different situations (Ryckman, 2012). Personality is an individual's characteristic pattern of emotions, thought, and behavior, together with the psychological mechanisms, which arises from those patterns (Funder, 2001).

Research has demonstrated a link between certain personality traits and the level of job satisfaction. For example, individuals with positive attitudes tend to have a higher level of job satisfaction (Staw & Ross, 1985). Furthermore, some personality traits may have a greater effect on job satisfaction than others (Greenberg & Baron, 1993). The trait of conscientiousness is linked to a better job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In contrast, individuals who have the neuroticism personality trait tend to have negative attitudes about their job and, hence, have a low level of job satisfaction (Rusting & Larsen, 1997; Uziel, 2006). According to Bruk-Lee et al. (2009), individuals who have neuroticism are less likely to be pleased with their current jobs. In general, Tokar and Subich (1997) evidenced that neuroticism plays a significant role in predicting job dissatisfaction level.

Individuals that have conscientious personality traits, in contrast, have high levels of job satisfaction, as they are willing to put in time and effort for their jobs (Bruk-Lee et al., 2009). Spector (1997) claims that, of all the personality traits, conscientiousness and neuroticism have the greatest effect on job satisfaction compared to other personality traits. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed to be tested:

H1a: The personality trait of conscientiousness has a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H1b: The personality trait of neuroticism has a negative relationship with job satisfaction.

Prior studies indicate that employees’ deviant behavior is associated with particular personality attributes (Bennett & Robinson, 2003; Dalal, 2005; Douglas & Martinko, 2001; Mount, Ilies, & Johnson, 2006; Salgado, 2002). Research on industrial and organisational psychology support this statement by proposing that individual differences may be able to predict deviant behavior in the workplace (Berry, Ones, & Sackett, 2007). According to Spector (2011), “personality has the potential to affect the counterproductive work behavior process at every step. It can affect people’s perceptions and appraisal of the environment, their attributions for causes of events, their emotional responses, and their ability to inhibit aggressive and counterproductive impulses” (p. 347). As we discuss in later paragraphs, we extend previous research by examining whether there are differential relationships between personality traits and dysfunctional audit behavior (premature sign-off).

In general, auditors were found to differ from each other on a wide variety of characteristics, including the need for achievement (Street & Bishop, 1991), Type A behavior pattern (Chadegani, Mohamed, & Iskandar, 2015; Kelley & Margheim, 1990; McNair, 1987; Mohd Nor, 2011), and locus of control (Baldacchino et al., 2016; Bryan, Quirin, & Donnelly, 2011; Chadegani et al., 2015; Paino, Smith, & Ismail, 2012). Intuitively, internal auditors would seem to vary in the degree to which they intend to engage in dysfunctional behaviors due, in part, to their personality traits.

The personality trait of conscientiousness has an impact on deviant behavior (Smithikrai, 2008). Researchers found that individuals who scored low on conscientiousness were more likely to participate in bad behavior at work (Mount & Barrick, 1995). Moreover, destructive behaviors, including absenteeism and lying, are more likely to occur in the workplace by individuals with low conscientiousness (Salgado, 2003). Low conscientious employees are characterised as untrustworthy, dishonest, and irresponsible, and are not hard workers (Salgado, 2003; Wanek, Sackett & Ones, 2003). In contrast, high conscientious individuals can be characterised as reliable, disciplined, and orderly (Roberts et al., 2005) and are typically high performing employees (Chandler, 2008). Thus, it is proposed that deviant behavior is more likely to occur in individuals with low conscientiousness.

On the other hand, neuroticism is often discussed in reference to emotional stability. Those high in neuroticism are susceptible to being anxious, depressed, and overall negativity (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Goldberg, 1993). The absence of these negative tendencies is associated with high emotional stability (Evans & Rothbart, 2007; Ghimbulu?, Ra?iu, & Opre, 2012). In general, neuroticism is related to negative characteristics (Gale et al., 2001). Highly neurotic individuals are characterised by less confidence and are more likely to be stressed. This may cause these individuals to use their efforts to avoid failure rather than to work hard to be successful (Barrick, Mount & Li, 2013). High levels of neuroticism is also associated with a higher likelihood to cheat in an educational setting (Jackson et al., 2002).

Berry et al. (2007) found that interpersonal and workplace deviance has a strong relationship with high levels of neuroticism. Therefore, the internal auditors who experience negative emotions (i.e. those who are high in neuroticism) are likely to engage in disproportionate amounts of premature sign-offs. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed to be tested:

H2a: The personality trait of conscientiousness has a negative relationship with premature sign-off.

H2b: The personality trait of neuroticism has a positive relationship with premature sign-off.

Job Satisfaction and Premature Sign-Off

Lock (1976) define job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (p. 1304). Based on this definition, it can be assumed that individuals are more likely to participate in dysfunctional behaviors if they have a negative appraisal of their job or work. This study uses a motivational approach to explain this phenomenon. From a theoretical perspective, the social exchange theory may help explain the relationship between job satisfaction and dysfunctional behavior (Gould, 1979; Levinson, 1965). According to the social exchange theory, individuals may feel upset or dissatisfied if they receive unfavourable treatment from their employer. Dissatisfied employees may exhibit destructive or negative behaviors in the workplace (Mount et al., 2006).

The deviant behavior-job satisfaction relationship was investigated by many studies. Among them, Bennett and Robinson (2003) and Bowling (2010) revealed that job dissatisfaction was related to deviant behavior, with Bowling (2010) stating that dissatisfied employees have a greater tendency to involve themselves in dysfunctional behavior to release stress. Pickett (2004) noted that, with so many roles to fill, many internal auditors become dissatisfied with their jobs, leading to unproductive environments. Such a negative correlation between the two variables was also supported by Srivastava (2012) and Dalal’s (2005) in their respective meta-analyses. Further, according to Tuna et al. (2016), lack of job satisfaction is the antecedent to deviant behaviors.

Westover (2012) examined a number of variables related to job satisfaction and their positive and negative outcomes. The study extended from 1989 to 2005. Westover (2012) defined job satisfaction as the level that an employee likes his job. According to this definition, high job satisfaction can bring about greater work quality, whereas low job satisfaction can result in low performance and low work quality. Lastly, Jidin, Lum, and Monroe (2013) found that auditors who were more intrinsically satisfied with their jobs will sign-off on a more conservative inventory amount, compared with auditors who are less satisfied with their jobs. Based on the findings reported by prior studies, the following hypothesis is, thus, proposed:

H3: A high level of job satisfaction is related to decreased premature sign-offs.

The Mediating effect of Job Satisfaction

From both a theoretical and empirical perspective, satisfaction has a mediating effect on behaviors in the workplace (Crede et al., 2007). In this study, it is proposed that job satisfaction is a contributing trait that can impact premature sign-offs. In particular, we look at the mediating effect that job satisfaction has on neuroticism and conscientiousness and dysfunctional audit behavior. In simpler terms, personality traits like neuroticism and conscientiousness may predispose employees to participate in activities that result in job satisfaction or dissatisfaction. In turn, this can influence individuals to conduct dysfunctional behaviors. This is consistent with the social exchange theory.

However, other factors aside from personality traits can impact dysfunctional behaviors. We propose that the main factor is the level of employee job satisfaction. In this study, we suggest that there is a direct relationship between job satisfaction and premature sign-offs, were highly dissatisfied employees are more likely to participate in dysfunctional behavior. To be specific, job satisfaction has a mediating effect on personality traits and premature sign-offs. Therefore, it is important to describe the association between personality traits and dysfunctional behaviors through the attitudes that individuals have about their work environment.For job satisfaction to be a mediator, job satisfaction must first be related to personality characteristics. Judge et al. (2002) found evidence to support of the relationship between job satisfaction and neuroticism and conscientiousness. In addition, job satisfaction must be associated with dysfunctional behavior, as proven in Jidin et al.’s (2013) study. On a final note, job satisfaction can be a significant indicator of the way employees perceive their jobs, and a predicting variable of work behaviors (e.g., organisational citizenship, absenteeism, and turnover). It can also be a partial mediator of the personality variables-dysfunctional behaviors relationship (?iarnien, Kumpikait, & Viena?indien, 2010). Thus, for this study, the following hypotheses will be tested:

For job satisfaction to be a mediator, job satisfaction must first be related to personality characteristics. Judge et al. (2002) found evidence to support of the relationship between job satisfaction and neuroticism and conscientiousness. In addition, job satisfaction must be associated with dysfunctional behavior, as proven in Jidin et al.’s (2013) study. On a final note, job satisfaction can be a significant indicator of the way employees perceive their jobs, and a predicting variable of work behaviors (e.g., organisational citizenship, absenteeism, and turnover). It can also be a partial mediator of the personality variables-dysfunctional behaviors relationship (?iarnien, Kumpikait, & Viena?indien, 2010). Thus, for this study, the following hypotheses will be tested:

H4a: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between the personality trait of conscientiousness and premature sign-off.

H4b: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between the personality trait of neuroticism and premature sign-off.

Model Development

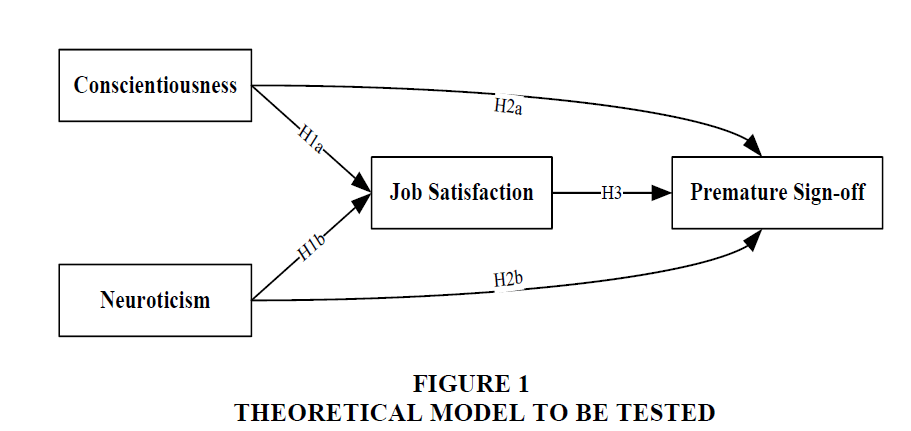

Fig. 1 presents the theoretical framework with hypothesized paths to be tested. The hypothesized model is derived from a fusion of prior auditing, accounting, organizational behavior, and psychological research. The positioning of satisfaction as a mediator between personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) and behavioral outcomes emanates from the Mount et al. (2006) model.

Our model examines the direct and indirect effects of both personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) on PMSO as mediated by job satisfaction. The mediator constructs serve as a predictor and is expected to transmit the influence of the personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) to PMSO. As a result, personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) are predicted to primarily affect PMSO through their influence on job satisfaction, and that any direct influence will be diminished by mediation effect.

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

The data were collected using a survey questionnaire over the period of five months from Sep 2015 to Feb 2016. The sample frame included all Jordanian companies listed on the Amman Stock Exchange ASE in 2015, amounting to 248 in total. Of the 385 questionnaires distributed, only 187 responses from internal auditors were valid, resulting in a response rate of 48.5%. The response rate achieved in this study is considered to be acceptable (Spector, 1992; Williams, Gavin, & Hartman, 2004).

Measurement Scales

The questionnaire survey was built based on previous literature. This research basically employed the currently validated scales of prior researches, such as Likert-type scales, with the range of response options from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”. The original items were in English translated into Arabic. Via a meticulous process, the research preserved validity by assuring that the questions were understood to prevent ambiguity.

Personality traits

In this study, 20 personality items were used to describe two traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness. Neuroticism: This study measured neuroticism using the 10 item scale for neuroticism. The measure includes items, such as “I seldom feel blue”, “I worry about things” (R), and “I change my mood a lot”. Conscientiousness: This was also measured using the 10 item. The measure includes items, such as “I like to be organised” “I leave my personal belongings around” (R), and “I am excited with my work”. These items were part of the revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) measure of the Big-Five Personality Traits developed by Costa and McCrae (1995).

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was gauged through the use of three questions adapted from the General Attitudes section of the Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire (MOAQ), as developed by Cammann et al. (1983)

Premature sign-off

This study used 12 items, based on the Ling and Akers (2010) instrument, to measure premature sign-offs in the internal audit environment.

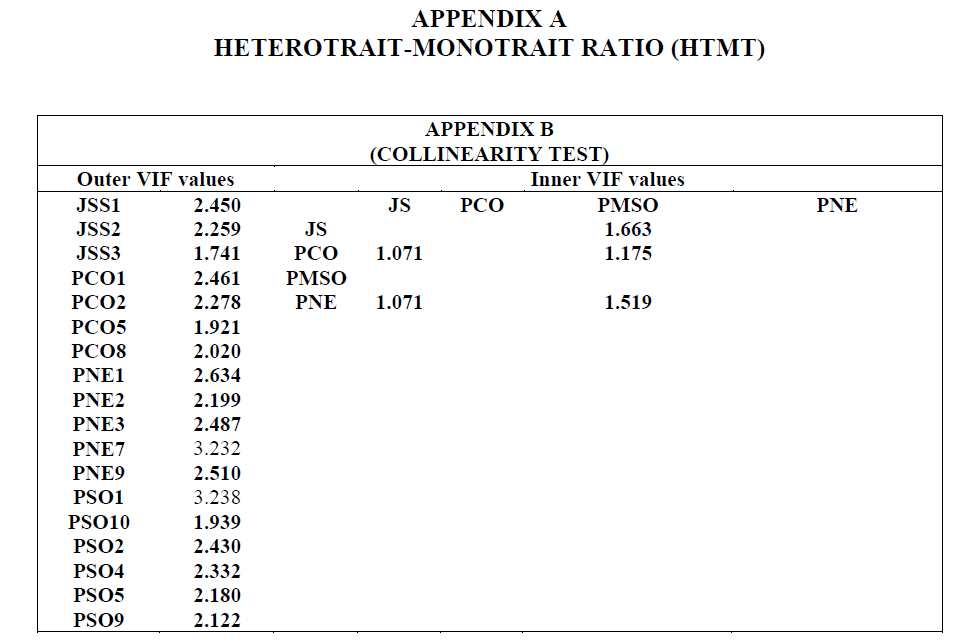

Common Method Bias (Variance)

In this study, data on the endogenous and exogenous variables were simultaneously collected utilising the same tool. Therefore, common method bias (CMB) could occur and potentially distort the gathered data. Podsakoff et al. (2003) referred to common method bias as the variance that is entirely attributable to the measurement procedure in comparison to the actual variables the measures represent. With this taken into consideration, our method employed the full collinearity test, as proposed by Rasoolimanesh et al. (2015). As stipulated by this method, CMB could be present if the values of VIF for each latent variable are much higher than one (Henseler, Hubona, & Ray, 2016). The analysis shows the minimum collinearity in each series of predictors in the structural model considering that the values of all variance inflation factor (VIF) are much less than the threshold value (5). Values of VIF that are less than five means the problem of multicollinearity does not exist (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011) (see Appendix B).

Results

The partial least squares (PLS) method for the structural equation modelling (SEM) was used in this study, using the statistical package SmartPLS 3 (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015). The PLS-SEM approach was chosen over other approaches, such as covariance-based statistics, for a number of reasons (Barroso, Carrión, & Roldán, 2010; Chin & Newsted, 1999; Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2013; Hair et al., 2011; Hairet al., 2016; Henseler, 2017; Reinartz, Haenlein, & Henseler, 2009). First, this study is exploratory, meaning that the relationship between job satisfaction and PMSO is not proven yet, so discovering a new interconnection is possible. Second, the amount of data collected is relatively small with only 187 cases. PLS is possible with smaller sample sets. Third, PLS does not require that the data be normally distributed because it is a nonparametric method. Fourth, this research focuses on predicting a model (job satisfaction and PMSO by means of personality traits). Fifth, PLS-SEM is becoming increasingly useful in explaining complex behavior research (Henseler et al., 2016), and is used to enhance the explanatory capacity of key target variables and their relationships (Hair et al., 2014). In the next section we discuss the results of the measurement model and analyse the structural model, according to a method proposed by Chin (1998), Marcoulides and Saunders (2006) and Hair et al. (2016).

Measurement model

| TABLE 1: Measurement Model |

|||||

| Construct | Items | Loadings | rhoAa | AVEb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality Traits | Conscientiousness | PCO1 | 0.879 | 0875 | 0.719 |

| PCO2 | 0.868 | ||||

| PCO5 | 0.824 | ||||

| PCO8 | 0.819 | ||||

| Neuroticism | PNE1 | 0.845 | 0.912 | 0.728 | |

| PNE2 | 0.827 | ||||

| PNE3 | 0.845 | ||||

| Job Satisfaction | PNE7 | 0.896 | 0.848 | 0.764 | |

| PNE9 | 0.852 | ||||

| JS1 | 0.903 | ||||

| JS2 | 0.878 | ||||

| JS3 | 0.840 | ||||

| Premature Sign-Off | PMSO1 | 0.883 | 0.907 | 0.676 | |

| PMSO2 | 0.827 | ||||

| PMSO4 | 0.832 | ||||

| PMSO5 | 0.794 | ||||

| PMSO9 | 0.811 | ||||

| PMSO10 | 0.778 | ||||

Note: arhoA = The most important reliability measure for PLS (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

bAVE = average variance extracted.

Reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests were conducted and the results confirm that all items used in the study are good indicators of the latent variables. The results reveal that all minimum requirements were met by the measurement models, as illustrated in Table 1. First, this study used a cut-off value of 0.70 significance for factor loadings (t-value > 1.96 and p-value < 0.05). The loadings of all items were above 0.778. A higher level of outer loading factors indicates a greater level of indicator reliability (Hair et al., 2013, 2011). Secondly, instead of using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability, Dijkstra-Henseler’s rho (rhoA), which provides a more accurate estimation of data consistency, is used and the values indicate that the items loaded on each construct were reliable (Ringle et al., 2017). Furthermore, all average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the threshold of 0.50, supporting the convergent validity of the construct measures (Henseler et al., 2016; Henseler, 2017).

| TABLE 2: Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (Htmt) | ||||

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | ||||

| PCO | 0.445 | |||

| PMSO | 0.563 | 0.308 | ||

| PNE | 0.662 | 0.292 | 0.460 | |

| SRMR composite model = 0.052 NFI normed fit index = 0.878 |

||||

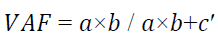

Lastly, the confirmation of discriminant validity of the analysis is made by (1) comparing the AVE's square root to the correlations (Table 2), (2) a cross loading analysis, and, most vitally, because (3) the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT)'s values (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2015) are lower than the (conservative) threshold of 0.85 (see Appendix A). According to Nitzl (2016), the HTMT should be used as a criterion to assess discriminant validity. As such, there is no issue with multi-collinearity in the outer model. Moreover, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and other fit indices, namely the normed fit index (NFI) are used to test the model fit of the research model (Henseler et al., 2014). SRMR produces a value of 0.052, that reaffirms the PLS path model’s overall fit (Hair et al., 2014 and Henseler et al., 2014). The NFI results in values between 0 and 1. The closer the NFI to 1, the better the fit (Ringle et al., 2017), all the results of the saturated model indicate that the model has a good fit (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Hair et al., 2016).

| TABLE 3: Significant Testing Results Of The Structural Model Path Coefficients | ||||

| Structural path | Path coefficient | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P-Values | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: PCO -> JS | 0.250 | 3.878 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1b: PNE -> JS | -0.519 | 7.738 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a: PCO -> PMSO | -0.092 | 1.138 | 0.255 | Not Supported |

| H2b: PNE -> PMSO | 0.196 | 2.379 | 0.017 | Supported |

| H3: JS -> PMSO | -0.346 | 4.291 | 0.000 | Supported |

| R2 Job Satisfaction = 0.399; Q2 Job Satisfaction = 0.286 R2 Premature Sign-Off = 0.280; Q2 Premature Sign-Off = 0.172 |

||||

Following the above analysis, for the final model, the reflective outer model was assessed for indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability and construct validity (convergent and discriminant). As was discussed, the model does not have any problem associated with these indicators.

Structural model

The structural model's results analysis draws on Hair et al. (2014)(Table 3). The analysis evidenced minimum collinearity in every series of predictors in the structural model, since the values of all variance inflation factor (VIF) are way lower than the threshold value which is 5. VIF values are lower than five indicate that there is no problem of multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2011) (see Appendix B). Furthermore, the R2 values of job satisfaction (0.399) and premature sign-off (0.280), which supports the in-sample predictive power of the model (Sarstedt et al., 2014). Likewise, results from blindfolding with an omission distance of 7 yield Q2 figures that are way beyond zero and positive value as recommended by Tenenhaus (1999), and therefore, the model's predictive relevance is supported in terms of out-of-sample prediction (Hair et al., 2012).

Applying the bootstrapping method in the assessment of path coefficients entails at least bootstrap sample of 5000 and the number of cases should equal the actual sample's number of observations (Hair et al., 2011). Moreover, the critical t-values for a two-tailed test is 1.65 (with a significance level of 10%), 1.96 (with a significance level of 5%), and 2.58 (with a significance level of 1%). The empirical results are in agreement with most of the hypothesized path model relationships among the constructs, especially, the conscientiousness positively and significantly influence job satisfaction (H1a). Nevertheless, as not supported to the hypothesis, the conscientiousness personality trait has a negative relation with premature sign-offs, but not significant (Path= -0.092, t= 1.138) (H2a), while neuroticism personality trait has a significant negative correlation with job satisfaction (H1b), and significant positive correlation with premature sign-offs (H2b). Finally, job satisfaction negatively and significantly related to premature sign-offs among internal auditors (H3).

Mediation test

So far, the direct effects of exogenous and endogenous latent variables (LVs) were discussed. But in this section, another aspect of the study can be argued. As was noted in previous studies that if the total effect (TE) of a LV on an endogenous variable would be larger than its direct effect (DE), then it could be concluded that the indirect (mediation) effect (IE) should be considered. In this regard, the results of the further analysis of the PLS-SEM about the indirect effect of the PCO and PNE on premature sign-off (PMSO) were provided (see Table 4). For the more, mediation analysis could also play an important role in prediction model (Shmueli et al., 2016). To test the mediation hypotheses (H4a and H4b), we follow the procedures suggested by Nitzl, Roldan, and Cepeda (2016) which suggested that mediating effect always exists when the indirect effect a × b is significant.

| TABLE 4: Test Of Mediation By Bootstrapping Approach | |||||||||

| Hypothesis | a | b | a*b | Total Effect (c) |

Percentile 95% confidence intervals | Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path coeff. | Path coeff. | Path coeff. | t-value | Path coeff. | 95% LL | 95% UL | VAF a | Bootstrapping | |

| PCO->JS->PMSO | 0.250 | -0.346 | -0.087 | 2.512** | -0.179 | (-0.167 ; -0.033) | 0.49 | P. M b | |

| PNE->JS->PMSO | -0.519 | -0.346 | 0.180 | 3.698* | 0.376 | (0.095 ; 0.284) | 048 | P. M b | |

`

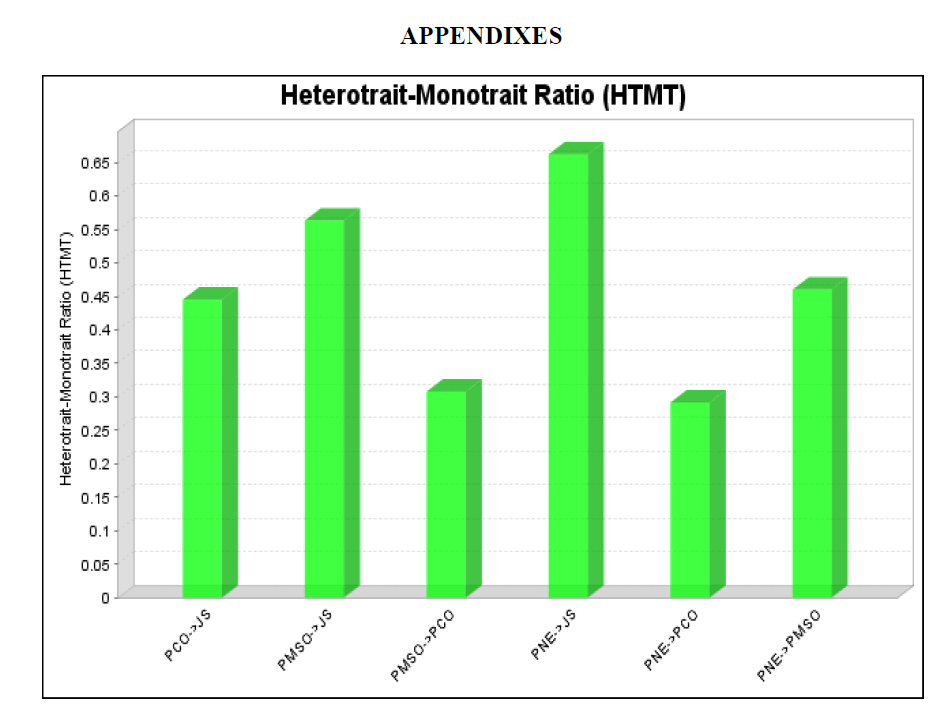

As Table 4 depicts, the indirect effect of PCO on PMSO is negative and significant (IE= -0.087 and t-value= 2.512) at p<0.05 as well as interval confidence was different from zero (-0.167, -0.033). In addition, the indirect effect of PNE on PMSO is positive and significant (IE= 0.180 and t-value= 3.698) at p<0.001 as well as interval confidence was different from zero (0.095, 0.284). Moreover, VAF is to calculate the ratio of the indirect-to-total effect (Nitzl & Hirsch, 2016). This ratio is also known as the variance accounted for (VAF) value. VAF determine the extent to which the process of mediation explains the variance of the dependent variable. For a simple mediation, the proportion of mediation is defined as:

Hair et al. (2016) stated that is if the VAF is less than 20%, one should conclude that nearly zero mediation occurs; a scenario in which the VAF is greater than 20% and lower than 80% could be classified as a typical partial mediation; and a VAF above 80% indicates a full mediation. In this study VAF values were greater than 20% and less than 80%. This means that JS considerable a partial mediator between PCO, PNE and PMSO.

Conclusion

Although prior research suggests that personality is associated with reduced audit quality (Mohd Nor, 2011), most studies focused on the target of the behavior rather than the type of behavior. We make a novel contribution by examining the relationships between personality traits with specific types of dysfunctional audit behaviors (PMSO) based on the social exchange theory. This suggests that job satisfaction is a mediator in this relationship, rather than the target. Our results indicate that internal auditors who possess high PCO tend to report higher levels of JS, but no direct relationship exists between PCO and PMSO, this result provide support for the hypothesized mediation model. Hence, part of the explanation for why PCO is not related to PMSO is because there is direct link whereby it is related to job satisfaction, which, in turn, is related to PMSO. The linkage was quite robust, as the results were consistently strong, and because that job satisfaction reflects nondispositional factors such as events and affect at work (Weiss et al., 1999) or other job influences (Mount et al., 2006). On the other hand, the internal auditors who possess high PNE tend to report lower levels of JS and higher levels of PMSO. Further, JS served as a partial mediator between PCO, PNE and PMSO. These results support the social exchange theory. In addition, the study confirms and extends connections made in the prior literature, specifically in terms of relationships between the antecedents of satisfaction and dysfunction outcomes. Our findings also add to the debate by confirming the central role of satisfaction as a mediating attribute in contributing to personality traits and premature sign-off relationship.

However, this study had a few limitations. Because this study looked at only one type of dysfunctional behavior, it is difficult to generalise our findings to other types of dysfunctional behaviors. Second, we tested our hypotheses together to maintain an adequate sample size to parameters ratio. When the sample size is appropriate, future research may benefit from examining higher-order level relationships between personality traits factor and dysfunctional audit behavior factors. Third, our study focused on JS as a mediator on the relationship between the traits of PCO, PNE and PMSO, and demonstrated its significance as a source to explain the reasons behind unethical behaviours among internal auditors. A promising future direction could include exploring additional factors, such as perceived job burnout, job engagement and job stress, as mediators of the personality traits-PMSO relationships. Finally, future research could examine the traits as a moderator between stressors and dysfunctional audit behaviours.

EndNotes

1. Neuroticism personality represents “an individual’s emotion regulation and tendency to experience negative feelings; people with low levels of neuroticism are calm, secure, emotionally stable and self-confident” (Woods & Sofat, 2013; p. 2207).

2. Conscientiousness personality reflects “a person’s reliability and self-control; a highly conscientious person is hard-working, responsible, self-disciplined and persistent” (Woods & Sofat, 2013; p. 2207).

References

- Abbott, L. J., Daugherty, B., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2016). Internal audit quality and financial reporting quality: The joint importance of independence and competence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 3-40.

- Arvey, R. D., Carter, G. W., & Buerkley, D. K. (1991). Job satisfaction: Dispositional and situational influences. International review of industrial and organizational psychology, 6, 359-383.

- Ayan, S., & Kocacik, F. (2010). The Relation between the Level of Job Satisfaction and Types of Personality in High School Teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(1), 27-41.

- Baldacchino, P. J., Tabone, N., Agius, J., & Bezzina, F. (2016). Organizational Culture, Personnel Characteristics and Dysfunctional Audit Behavior. IUP Journal of Accounting Research & Audit Practices, 15(3), 34.

- Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis. Personnel psychology, 44(1), 1-26.

- Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Judge, T. A. (2001). Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1-2), 9-30.

- 7Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K. & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Academy of management Review, 38(1), 132-153.

- 8Barroso, C., Carrión, G. C., & Roldán, J. L. (2010). Applying maximum likelihood and PLS on different sample sizes: studies on SERVQUAL model and employee behavior model Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 427-447): Springer.

- 9Bayarçelik, E. B., & Findikli, M. A. (2016). The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on the Relation Between Organizational Justice Perception and Intention to Leave. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 403-411.

- Bennett, R., & Robinson, S. (2003). The past, present and future of workplace deviance research. In Greenberg J (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (2nd ed., pp. 247–281). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2003). The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research.

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological bulletin, 88(3), 588.

- Berry, C., Ones, D., & Sackett, P. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organisational deviance and their common correlates: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 410-424.

- Bowling, N. A. (2010). Effects of job satisfaction and conscientiousness on extra-role behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(1), 119-130.

- Bruk-Lee, V., Khoury, H. A., Nixon, A. E., Goh, A., & Spector, P. E. (2009). Replicating and extending past personality/job satisfaction meta-analyses. Human Performance, 22(2), 156-189.

- Bryan, D. O., Quirin, J. J., & Donnelly, D. P. (2011). Locus Of Control And Dysfunctional Audit Behavior. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 3(10).

- Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, G., & Klesh, J. (1983). Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members, in Seashore, S.E., Lawler, E.E. III, Mirvis, P.H. and Cammann, C. (Eds), Assessing Organizational Change: A Guide to Methods, Measures, and Practices: New York: Wiley-Interscience, NY, pp. 71-138.

- Chadegani, A. A., Mohamed, Z. M., & Iskandar, T. M. (2015). The Influence of Individual Characteristics on Auditors’ Intention to Report Errors. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3(7), 710-714.

- Chandler, M. M. (2008). Examining the mechanisms by which situational and individual difference variables relate to workplace deviance: the mediating role of goal self-concordance. The University of Akron.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–358). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

- Chin, W. W., & Newsted, P. R. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Statistical strategies for small sample research, 1(1), 307-341.

- ?iarnien, R., Kumpikait, V., & Viena?indien, M. (2010). Expectations and job satisfaction: Theoretical and empirical approach: Proceeding of The 6th International Scientific Conference “Business and Management 2010, Vilnius, Lithuania, May.13-14, 2010. Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Publishing House: Vilnius, 2010.

- Connolly, J. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2000). The role of affectivity in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Personality and individual differences, 29(2), 265-281.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of personality assessment, 64(1), 21-50.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and individual differences, 13(6), 653-665.

- Crede, M., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., Dalal, R. S., & Bashshur, M. (2007). Job satisfaction as mediator: An assessment of job satisfaction's position within the nomological network. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(3), 515-538.

- Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of applied psychology, 90(6), 1241-1255.

- Diener, E., Larsen, R. J., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). Person× Situation interactions: Choice of situations and congruence response models. Journal of personality and social psychology, 47(3), 580-592.

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS quarterly= Management information systems quarterly, 39(2), 297-316.

- Douglas, S. C., & Martinko, M. J. (2001). Exploring the role of individual differences in the prediction of workplace aggression. Journal of applied psychology, 86(4), 547.

- Endler, N. S., & Edwards, J. M. (1985). Evaluation of the state trait distinction within an interaction model of personality. Southern Psychologist, 2(4), 63–71.

- Endler, N. S., & Edwards, J. M. (1986). Interactionism in personality in the twentieth century. Personality and Individual Differences, 7(3), 379–384.

- Evans, D. E., & Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Developing a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 868-888.

- Funder, D. C. (2001). The personality puzzle (2nd éd.).

- Furnham, A., Petrides, K., Jackson, C. J., & Cotter, T. (2002). Do personality factors predict job satisfaction? Personality and individual differences, 33(8), 1325-1342.

- Gale, A., Edwards, J., Morris, P., Moore, R., & Forrester, D. (2001). Extraversion–introversion, neuroticism–stability, and EEG indicators of positive and negative empathic mood. Personality and individual differences, 30(3), 449-461.

- Ghimbulu?, O., Ra?iu, L., & Opre, A. (2012). Achieving resilience despite emotional instability. Cognitie, Creier, Comportament/Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 16(3), 465-480.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American psychologist, 48(1), 26-34.

- Gould, S. (1979). An equity-exchange model of organizational involvement. Academy of management Review, 4(1), 53-62.

- Greenberg, J., & Baron, R. (1993). Behavior in organisation (4" ed.).

- Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt. (2013). Editorial-partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1-12.

- Hair, Ringle, M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

- Hair, Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414-433.

- Hair , F., Hult, M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): Sage Publications.

- Hair, J., F, Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed): Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121.

- Henseler, Hubona, G., & Ray, P. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2-20.

- Henseler, Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging Design and Behavioral Research With Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of advertising, 1-15.

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., . . . Calantone, R. J. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational research methods, 17(2), 182-209.

- Hodge, C. (2012). Organizational Satisfaction in the 21st-Century Internal Audit Function: Trends That Impact Internal Audit Departments. JONES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY.

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms.

- Ilies, R., Fulmer, I. S., Spitzmuller, M., & Johnson, M. D. (2009). Personality and citizenship behavior: the mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of applied psychology, 94(4), 945-559.

- Jackson, C. J., Levine, S. Z., Furnham, A., & Burr, N. (2002). Predictors of cheating behavior at a university: A lesson from the psychology of work. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(5), 1031-1046.

- Jex, S. M., & Britt, T. W. (2014). Organizational psychology: A scientist-practitioner approach: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jidin, R., Lum, J., & Monroe, G. (2013). The Effect of Auditors’ Job Satisfaction on the Influence of Ethical Conflict on Auditors’ Inventory Judgments.Paper presented at the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand (AFAANZ) Conference, Perth, Australia.

- Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology, 87(3), 530.

- Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999). The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel psychology, 52(3), 621-652.

- Judge, T. A., & Zapata, C. P. (2015). The person–situation debate revisited: Effect of situation strength and trait activation on the validity of the Big Five personality traits in predicting job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 1149-1179.

- Kelley, T., & Margheim, L. (1990). The impact of time budget pressure, personality, and leadership variables on dysfunctional auditor behavior. Auditing-A Journal Of Practice & Theory, 9(2), 21-42.

- Levinson, H. (1965). Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organization. Administrative science quarterly, 370-390.

- Ling, Q., & Akers, M. (2010). An Examination Of Underreporting Of Time And Premature Signoffs By Internal Auditors Review of Business Information Systems, 14(4), 37-48.

- Locke, E. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In: M. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pages 1297-1349). .

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Common method bias in marketing: causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4), 542-555.

- Marcoulides, G., & Saunders, C. (2006). Editor's comments: PLS: a silver bullet? MIS Quarterly, 30(2), iii-ix.

- McNair, C. J. (1987). The effects of budget pressure on audit firms: An empirical examination of the underreporting of chargeable time. Columbia University New York, NY.

- Mohd Nor, M. N. (2011). Auditor stress: antecedents and relationships to audit quality. Ph.D. dissertation, Edith Cowan University, Australia. .

- Mount, M., & Barrick, M. (1995). The Big Five personality dimensions: Implications for research and practice in human resources management. Research in personnel and human resources management, 13(3), 153-200.

- ount, M., Ilies, R., & Johnson, E. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effects of job satisfaction. Personnel psychology, 59(3), 591-622.

- Nitzl, C. (2016). The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. Journal of Accounting Literature, 37, 19-35.

- Nitzl, C., & Hirsch, B. (2016). The drivers of a superior’s trust formation in his subordinate: The manager–management accountant example. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 12(4), 472-503.

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849-1864.

- O'Leary, C., & Stewart, J. (2007). Governance factors affecting internal auditors' ethical decision-making: an exploratory study. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(8), 787-808.

- Paino, H., Smith, M., & Ismail, Z. (2012). Auditor acceptance of dysfunctional behavior: An explanatory model using individual factors. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(1), 37-55.

- Pickett, K. S. (2004). The internal auditor at work: A practical guide to everyday challenges: John Wiley & Sons.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879-903.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual review of psychology, 63, 539-569.

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531-544.

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ramayah, T. (2015). A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents' perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 335-345.

- Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International journal of research in marketing, 26(4), 332-344.

- Ringle, Wende, S., & Becker, J. (2015). "SmartPLS 3." Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Retrieved from .

- Ringle, C., Wende, S., Becker, J., & GmbH, R. (2017). SmartPLS - Statistical Software For Structural Equation Modeling [Internet]. Smartpls.com. 2017 [cited 2017 March 18]. Available from:

- Roberts, B. W., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., & Goldberg, L. R. (2005). The structure of conscientiousness: An empirical investigation based on seven major personality questionnaires. Personnel psychology, 58(1), 103-139.

- Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1997). Extraversion, neuroticism, and susceptibility to positive and negative affect: A test of two theoretical models. Personality and individual differences, 22(5), 607-612.

- Ryckman, R. M. (2012). Theories of personality: Cengage Learning.

- Salgado, J. (2003). Predicting job performance using FFM and non-FFM personality measures. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), 323-346.

- Salgado, J. F. (1997). The Five Factor Model of personality and job performance in the European Community. Journal of applied psychology, 82(1), 30.

- Salgado, J. F. (2002). The Big Five personality dimensions and counterproductive behaviors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10(1-2), 117-125.

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Henseler, J., & Hair, J. F. (2014). On the emancipation of PLS-SEM: A commentary on Rigdon (2012). Long Range Planning, 47(3), 154-160.

- Schneider, B., & Dachler, H. P. (1978). A note on the stability of the Job Descriptive Index. Journal of applied psychology, 63(5), 650.

- Shapeero, M., Chye Koh, H., & Killough, L. N. (2003). Underreporting and premature sign-off in public accounting. Managerial Auditing Journal, 18(6/7), 478-489.

- Shmueli, G., Ray, S., Estrada, J. M. V., & Chatla, S. B. (2016). The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4552-4564.

- Smithikrai, C. (2008). Moderating effect of situational strength on the relationship between personality traits and counterproductive work behavior. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(4), 253-263.

- Spector, P. E. (1992). A consideration of the validity and meaning of self-report measures of job conditions. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology West Sussex, England: John Wiley, 123.

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences (Vol. 3): Sage publications.

- Spector, P. E. (2011). The relationship of personality to counterproductive work behavior (CWB): An integration of perspectives. Human Resource Management Review, 21(4), 342-352.

- Srivastava, S. (2012). Workplace passion as a moderator for workplace deviant behavior–job satisfaction relationship: A comparative study between public sector and private sector managers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 8(4), 517-523.

- Staw, B. M., & Ross, J. (1985). Stability in the midst of change: A dispositional approach to job attitudes. Journal of applied psychology, 70(3), 469.

- Street, D. L., & Bishop, A. C. (1991). An empirical examination of the need profiles of professional accountants. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 3(1), 97-116.

- Sun, Y., Gergen, E., Avila, M., & Green, M. (2016). Leadership and Job Satisfaction: Implications for Leaders of Accountants. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6(03), 268.

- Svanström, T. (2016). Time pressure, training activities and dysfunctional auditor behavior: evidence from small audit firms. International Journal of Auditing, 20(1), 42-51.

- Tanoff, G. F. (1999). Job satisfaction and personality: The utility of the Five-Factor Model of personality. ProQuest Information & Learning.

- Tenenhaus, M. (1999). L'approche PLS. Revue de statistique appliquée, 47(2), 5-40.

- Therasa, C., & Vijayabanu, C. (2015). The Impact of Big Five Personality Traits and Positive Psychological Strengths towards Job Satisfaction: a Review. Periodica Polytechnica. Social and Management Sciences, 23(2), 142.

- Thomas, J. C., & Segal, D. L. (2006). Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology, Personality and Everyday Functioning (Vol. 1): John Wiley & Sons.

- Tokar, D. M., & Subich, L. M. (1997). Relative contributions of congruence and personality dimensions to job satisfaction. Journal of vocational behavior, 50(3), 482-491.

- Tuna, M., Ghazzawi, I., Yesiltas, M., Tuna, A. A., & Arslan, S. (2016). The effects of the perceived external prestige of the organization on employee deviant workplace behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(2), 366-396.

- Uziel, L. (2006). The extraverted and the neurotic glasses are of different colors. Personality and individual differences, 41(4), 745-754.

- Wanek, J. E., Sackett, P. R., & Ones, D. S. (2003). Towards an understanding of integrity test similarities and differences: an item-level analysis of seven tests. Personnel psychology, 56(4), 873-894.

- Weiss, H. M., Nicholas, J. P., & Daus, C. S. (1999). An examination of the joint effects of affective experiences and job beliefs on job satisfaction and variations in affective experiences over time. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 78(1), 1-24.

- Westover, J. H. (2012). Comparative international differences in intrinsic and extrinsic job quality characteristics and worker satisfaction, 1989-2005. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7).

- Williams, L. J., Gavin, M. B., & Hartman, N. S. (2004). STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING METHODS IN STRATEGY RESEARCH: APPLICATIONS AND ISSUES. Research Methodology in Strategy and anagement, 1, 303-346.

- Woods, S. A., & Sofat, J. A. (2013). Personality and engagement at work: The mediating role of psychological meaningfulness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(11), 2203-2210.