Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 4S

The innovation linkages in Europe

Alberto Costantiello, Lum-University

Lucio Laureti, Lum-University

Angelo Leogrande, Lum-University

Marco Matarrese, Lum-University

Citation Information: Costantiello, A., Laureti, L., Leogrande, A., & Matarrese, M. (2022). The Innovation Linkages in Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 26(S4), 1-13.

Abstract

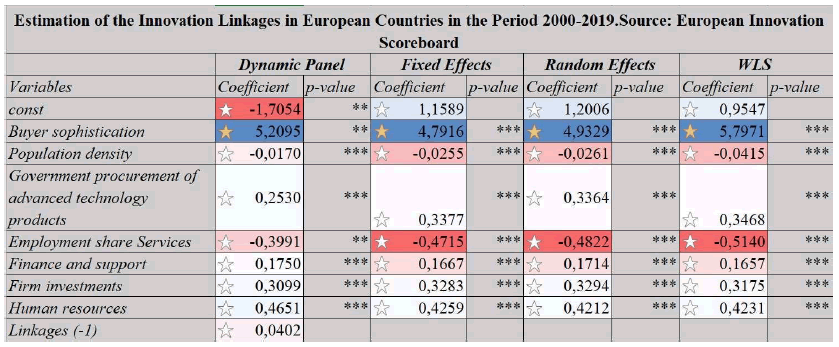

In this article we investigate the determinants of the Innovation Linkages in Europe. We use data from the European Innovation Scoreboard of the European Commission in the period 2000-2019 for 36 countries. Data are analyzed using Panel Data with Fixed Effects, Random Effects, Dynamic Panel at 1 Stage, Dynamic Panel at 2 Stage, Pooled OLS, WLS. Results show that the Innovation Linkages in Europe is positively associated with “Buyer Sophistication”, “Government Procurement of Advanced Technology Products”, “Finance and Support”, “Firm Investments”, “Human Resources”, and negatively associated with “Population Density”, “Employment Share Services”.

Keywords

Innovation, Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives, Management of Technological Innovation and R&D, Diffusion Processes, Open Innovation.

JEL Codes: O30, O31, O32, O33, O36.

Introduction

In this article we investigate the role of linkages among SMES and the ability of public and private organizations to cooperate to innovate and generate economic values through investments in Research and Development. We try to question if innovation can benefit from the cooperation among firms and between the private and the public sector. Innovation is an essential tool to promote economic growth in the long run through the increasing in the efficiency of labor (Solow, 1956) and technological change in the context of endogenous growth theory (Romer, 1994). Innovation is relevant also in the Schumpeterian economics either as driving forces in the creative-destruction process either as a tool to promote economic development (Schumpeter & Opie, 1934).

Industrial Districts

The theory of industrial districts has emphasized the connections among SMEs in the context of local development with attention to the productive vocation of regional, territorial and either rural area. Industrial districts have been introduced in the scientific work of Alfred Marshall (Marshall, 1920) and have been developed in the economic theory of the Italian economist Giacomo Becattini (2004). Industrial districts can promote deeper connection among SMEs and in the sense of the public-private partnership. Specifically, industrial districts consent to create productive specialization through a common scientific and professional knowledge that is shared among firms and workers. The presence of deeper connections among firm can also promote an orientation toward innovation in the specific sector of the industrial district. Globalization has reduced the ability of districts to compete due to de-localization of industrial activity in low-income countries. But the Fourth Industrial Revolution based on Artificial Intelligence-AI, Machine Learning-ML and Big Data- BD, have crated new opportunities for industrial districts as a methodology to promote the relationships among makers, inventors, digital entrepreneurs, startups, newcos and high-tech SMEs. The Fourth Industrial Revolution has re-created the economic and productive characteristics to sustain a new form of industrial districts that in the general context of knowledge economy are more oriented to produce technological innovation either in the Business to Business-B2B either in the Business to Customer-B2C markets. Specifically, industrial district are relevant for the fact to create, promote and defend codified and tacit knowledge that (Becattini, 2002) constitutes the basis for innovative products and services. Since industrial district consent the accumulation of the tacit knowledge (Polanyi, 2009) and since tacit knowledge is an essential component of learning by doing [8] that is productive factor in the innovation function then the construction of industrial districts can be considered as an active political economy to promote the linkages-innovation nexus among SMEs.

Social Capital, Human Capital, and Networks of Knowledge

The role of social capital, human capital, and networks of knowledge in promoting economic growth has been analyzed by the Chilean physicist Cesar Hidalgo (Arrow, 1971). Specifically, the idea of linkages must be considered in connection with the question of proximity in the context of knowledge diffusion. Innovative systems are based on cooperation and collaboration among SMEs and these positive outcomes in terms of relationships are feasible due to the proximities of firms. These considerations among the relevance of proximities to promote collaboration in the sense of innovation and knowledge also hold for countries (Bahar, Hausmann & Hidalgo, 2014). The fact that firms are related can effectively predict the ability of a certain local area to produce effectively. There is a relationship among skills, technology, and knowledge in respect to a certain space or territory. Economic activities develop connections and the principle of relatedness (Hidalgo et al., 2018) can also explain the ability of certain geographical area to be extremely productive in the sense of innovation, Research and Development and high-level technologies. The principle of relatedness among economic activities, with a particular attention for the question of innovation, can suggest to policy makers to promote incentives among firms to create deeper linkages with the objective of create new products and services. Economic activities have the tendency of concentration i.e. the presence of a certain typologies of firm creates incentives for the installation of other similar firms. This is an argument in favor of the idea of the industrial district even in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In effect the concentration of firms, in a physical space, continues notwithstanding the development of internet and ubiquitous communication systems. Balland (2020) shows how firms tend to concentrate controlling for some factors such as technologies, scientific publications, industries, and occupations. Furthermore, the concentration of economic activities in a certain physical space increases with the complexity of firms on organizational and productive perspectives. The consequences are that there are clusters, social and spatial conglomerate of firms that tend to share innovation, to create jobs and to participate of a similar scientific, professional and productive knowledge. This means that effectively not only linkages are a tool to promote innovation among SMEs, but that SMEs need to relate with other firms to cooperate, collaborate, and even to compete, in the context of the production of new products and services.

The article continues as follows: the second paragraph presents the literature review, the third paragraph contains the econometric model and discusses the main results, the fourth paragraph concludes.

Literature Review

Chybowska, et al., (2018) afford the question of the financing of research and development in Poland economy. The authors consider the long-term ambition of the Poland economy that is that to evolve in a knowledge economy. In the period 2004-2017 Poland has received 149,5 billion of euros from the European Union to boost innovation, research and development, human capital, and the level of intangibles in the real economy. The authors analyze three main elements of the Poland Research and Development expenditures and investments that are:

- Sources: are defined as business, government, or higher education sectors;

- Types: European Union or Statal Aid;

- Areas of support: infrastructure, education, and innovation.

Ple?niarska (2018) affords the question of the relationship between the academia and the private sector as a mean to promote a knowledge economy in the European Union. The business sector and the academia have mutual interests in investing in knowledge, research and development and human capital. The author concludes that:

- In many member states such as Denmark, Sweden, and Finland there are high quality relationships between science and business;

- Large companies are more oriented to engage in collaboration with universities and research institutes.

Open Innovation

Sa?, Sezen & Güzel (2016) afford the question of open innovation in SMEs. SMEs can use open innovation to promote technological and organizational change. But the authors find that the impact of Open Innovation on SMEs performance is controversial, especially in developing countries.

Results show that SMEs are more able to promote open innovation if policy makers and public institutions:

- create incentives to boost the relationships between SMEs and universities;

- promote the networking ability of SMEs through innovation hub;

- offer services to boost the ability of SMEs in managing intellectual property rights.

Theyel (2013) analyzes the relationship among open innovation, firm’s value chain and product and process innovation. The author considers 293 SMEs in USA and found a wide usage of open innovation practices. Findings suggest that at least 50 percent of the firms perform open innovation during the phases of product development and commercialization, while only 33% of the firms use open innovation in manufacturing.

De Marco, Martelli & Di Minin (2020) introduce a new methodology to analyze the ability of firms to promote Open Innovation in Europe. Specifically, the authors consider the efficacy of the European Union in publicly financing SMEs in their efforts to innovate in the digital sector. Results show that firms that obtain public grants are less oriented to perform Open Innovation in respect to firms that did not receive financial support. The results are counterfactual and in contradiction with the inspiration of European political economies oriented to financially sustain open innovation among SMEs.

Leckel, Veilleux & Dana (2020) afford the question of the role of public financial support in improving collaboration among firms, entrepreneurs, research organizations and institutions in the sense of innovation and Research and Development for SMEs. The authors suggest a local strategy i.e. the “Local Open Innovation”- LOI to create regional incentive to promote technological innovation and Research and Development. The local approach to open innovation-LOI- offers some alternative solutions to solve the question of the presence of scarcity in the access to cognitive resources. The authors suggest that the local approach to Open Innovation- LOI- can improve the efficiency of SMEs in creating new products and services overcoming the limitations of cognitive resources and intangibles.

Padilla-Meléndez, et., (2013) afford the question of the relationships among social capital, higher education institutions and spin offs in transferring knowledge towards Small and Medium Enterprises in the context of the open innovation. The aim of the study is to evaluate the ability of the firm to translate scientific and professional knowledge developed in universities and research institutes in products and services produced in Small and Medium Enterprises. Data are collected through interviews in the Spanish region of Andalucía. Results show that to promote a deep transfer of knowledge from universities and research institutes to the industrial systems it is necessary to recognize the role of:

- Intellectual property contracts;

- boost formal and informal relationships among stakeholders at a regional and local level;

- create a culture of cooperation in the context of open innovation.

Bigliardi & Galati (2016) consider the question of the relationship between SMEs and open innovation. The authors have a threefold objective:

- To investigate the obstacles that reduces the ability of SMEs to participate in open innovation;

- To analyze if there are differences among SMEs in their relationship with open innovation;

- To find empirical evidence of the characteristics that help SMEs to successfully implement an open innovation strategy.

Data are collected from 157 Italian SMEs. The authors classify the SMEs in respect to open innovation based on the sequent elements:

- The presence of barriers to open innovations that are knowledge, collaboration, organization and finance and strategy;

- Different typology of firms in respect to innovation that are knowledge intensive, medium- innovative, and less innovative.

Schuurman, et al., (2016) analyze the role of Living Labs in the context of open innovation. The authors try to find the presence of best practices that can be used to promote deeper innovation the productive process of firms. Living Labs are considered as an essential tool to promote research and development in the scenario of open innovation. Living Labs are relevant for their ability to relate utilizers and users. The main stakeholders of a Living Lab are citizens as potential users, local private companies as potential utilizers and local organizations as potential providers. Living Labs also operate as instrument for community building among different stakeholders in the urban context of the city. Results show that Living Labs are the solution to solve the question of a low orientation of SMEs toward the open innovation process.

Public and Private Founding of Research and Development and Innovation

Wältermann, Wolff & Rank (2019) consider the role of institutionalized clusters in their ability to produce connection among firms of different regions and sectors. These connections can boost policies oriented to promote deeper relationships among firms and industries. The authors analyze the role of private and public funding on the propensity of firms and managers of different clusters to cooperative and enter in productive relationships. Data are collected from 82 clusters in Germany. Results show that:

- Private founded clusters tend to create fewer partnerships in respect to public founded clusters;

- Managers of private founded clusters have a deeper ability to cooperative in respect to private founded managers, at least at an informal level.

Crespi (2020) analyze the impact of two grant schemes in promoting private investment in Research and Development in Chile. The authors try to estimate the impact of Chilean policies in promoting firms productivity through the incentives in innovation. The two public programs analyzed are:

- The National productivity and Technological Development Fund-FONTEC- that subsidizes intramural R&D;

- The Science and Technology Development Fund-FONDEF that finance extramural R&D in collaboration to other research institutes.

The results show that:

- The FONDEF program has produced positive spillovers on firm’s productivity;

- Exists an inverted U-relationship between the intensity of public support and the presence of spillover effects on productivity;

- If firms and research institutes are in a technological and geographical proximity then the spillover effect growths.

Raudla (2015) afford the question of the methodology to finance research in public universities through the methodology of project-based management. The authors analyze two large universities in Estonia to evaluate the impact of project-based founding on the performance of the academic institutions. Results show that the project-based founding in Estonian universities is associated to the sequent economic consequences:

- Fluctuating revenues;

- Fragmented revenues sources;

- High transaction costs;

- Coordination problems;

- High complexity in managing the finances;

- Difficulties in securing cash flows;

- Problems in covering indirect costs.

Finally, the authors show that the more the Estonian universities are oriented to project based financing the more austere the budget constraint become.

Bondonio, Biagi & Stancik (2016) analyze the role of private and public funding on firms’ performance with attention to investment in R&D in Europe. The results show that:

- Either national funding either European funding is relevant in boosting firm’s product and process innovation;

- EU funding has a deeper correlation to firms’ correlation in respect to national funding;

- There is a positive correlation between public funding of private R&D and product innovation;

- There is a positive association between public support to private investment and process innovation;

- There is not a positive relationship between public support to private investment and product innovation;

- SMEs that receive national public financial support increment employment, sales and value added;

- EU funds do not improve marginally employment, sales and value added in the presence of national funding of private investments.

SMEs Collaboration

Casals (2011) analyzes the methodology through which SMEs cooperate in the sense of Research and Development and innovation. The authors specifically consider the role of interfirm co- operation. Results show that co-operation among SMEs is a strategy to promote firm performance and improve the ability to create successful alliances in the future.

Martínez-Costa (2019) affords the question of the relationship among innovation, firms’ collaboration, and organizational learning processes. The authors consider the inter-organizational collaborations and the organizational learning because of the SMEs innovative culture. Data are collected from 500 Spanish SMEs. Results show that:

- SMEs’ innovative culture promotes either inter-organizational collaboration;

- SMEs’ innovative culture improves organizational learning;

- Employees can perform product and process innovations through a management of the external knowledge.

SMEs can growth in their ability to innovate creates a deeper connection between external collaboration with other firms and a better usage of internal knowledge management.

Linkages among Countries to Promote Innovation and Research and Development

Zygmunt (2019) affords the relationship among external linkages and intellectual assets in promoting innovation. Specifically, the author considers the relationship between Czech and Poland firms in the sense of innovation and Research and Development. Data are collected from the European Innovation Scoreboard in the period 2008-2015 to investigate private co-funding of public R&D expenditures, innovative SMEs collaborating with others, PCT patent applications and trademark applications. The results show the presence of a positive impact of external linkages and intellectual assets on the ability of Czech and Polish firms to innovate.

University-Firm Collaboration

Siripitakchai & Miyazaki (2015) afford the question of the relationship between universities and firms in Thailand. The authors analyze the output through the analysis of an indicator able to represent the level of co-patents and co-publications. Data are collected from Thailand’s patent database. The results show that:

- A large portion of co-patents and co-publishing has been realized in collaboration between universities and low and medium tech sectors;

- The collaboration between universities and the high-tech sector is policy-invariant;

- The relationship between universities and the high-tech sectors includes incumbent and exclude newcos.

Abramo, D’Angelo & Solazzi (2010) analyze the role of the relationship between the private and the public research sector to promote economic growth and innovation at a regional and local level with positive impact on the industrial productivity. The authors use a bibliometric approach to evaluate the presence co-authorship publication as the result of the co-operation between public research institutions and the private sector. Data are analyzed with a new algorithm able to discern among publications to find the appropriate identification. The methodology used can offer a metric tool to evaluate the ability of the university-firm linkages in promoting industrial spillovers at a regional ed extra-regional level. The authors promote their methodology as a tool for policy making.

Lam, Hills & Ng (2013) consider the strategic role of innovation in the creation of a competitive advantage for SMEs in Hong Kong. The authors investigate the role of open innovation in generating new perspective for firms, especially deepening the relationship between SMEs and universities to promote the implementation of external knowledge in the productive process. The government of Hong Kong has promoted a political economy based on open innovation to generate a deeper connection between universities and SMEs. To improve the relationship between academic institutions and firms, the government has introduced new Research and Development program based with a focus on Innovation and Technology applied to environment and energy. The authors have analyzed 145 of 2345 funded projects in the period 2009-2010 with a qualitative and quantitative approach. The results show that local industries are interested in a collaborative partnership with universities in the culture of open innovation. But some institutional constraints limit the ability of local SMEs to enter in a profitable relationship with universities. The authors suggest promoting political economies based on innovation to create the condition of a more collaborative environment between universities and SMEs.

Bye & Raknerud (2019) analyzes the role political economies that incentivize R&D in Norway. Specifically, the authors consider either R&D tax credits either direct R&D subsidies with a focus on patents. Direct subsidies remunerate projects with high social returns that are characterized by a low profitability. Tax credits incentivize either technologies either projects. The authors find that either direct subsidy either tax credits have an impact on patenting. Specifically, the incentive operates better for firms that before the political intervention do not have registered any patent. Finally, results show that incentives can promote innovation that can benefit the society.

The econometric model to estimate the degree of innovation linkages among European countries in the period 2000-2019

We estimate the sequent model:

Linkagesit = a1 + b1(BuyerSopMistication)it + b2(PopulationDensity)it

+ b3(GovernmentProcurementO†AdvancedTecMnologyProducts)it

+ b4(EmploymentSMareServices)it + b5(FinanceAndSupport)it

+ b6(FirmInvestments)it + b7(HumanResources)it

With i = 36 and t = [2000; 2019].

Since:

Linkagesit = b1(InnovativeSMEsCollaboratingWitMOtMers)it

+ b2(PublicPrivateCoPublications)it

+ b3(PrivateCoFoundingO†PublicR&DExpenditures)it

With i = 36 and t = [2000; 2019], then

InnovativeSMEsCollaboratingWitMOtMersit + PublicPrivateCoPublicationsit

+ PrivateCoFoundingO†PublicR&DExpendituresit

= a1 + b1(BuyerSopMistication)it + b2(PopulationDensity)it

+ b3(GovernmentProcurementO†AdvancedTecMnologyProducts)it

+ b4(EmploymentSMareServices)it + b5(FinanceAndSupport)it

+ b6(FirmInvestments)it + b7(HumanResources)it

With i = 36 and t = [2000; 2019].

Figure 1 Estimation of the innovation linkages in European countries in the period 2000-2019 with dynamic panel at 1 stage, panel data with fixed effects, panel data with random effects, weighted least squares-WLS. source: European innovation scoreboard

We found that Linkages is positively associated to:

- Buyer sophistication: is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard define as the « Average response to the following question: “In your country, on what basis do buyers make purchasing decisions? [1 = based solely on the lowest price; 7 = based on sophisticated performance attributes]” (Hollanders, 2017). There is a positive relationship between buyer sophistication and private-public innovation linkages. The more consumers are sophisticated in their buying behavior the greater the incentive for firms to develop public-private partnership in the sense of innovation and to promote cooperation among SMEs to improve the technologies. The orientation that firms have towards cooperation with other firms, or in creating partnerships with the public sector, depends, on a certain extent, on the sensibility that consumers have in respect to the technological characteristics of products. But effectively the buyer sophistication depends from sociological, cultural and anthropological features and specifically on the level of human capital since extracting consumer surplus from technological complex products and services require some scientific and professional knowledge at least in the act of consumption and as an orientation towards the benefit that high tech product and services can generate not only in the material sense but also in the sense of intangibles and self-perception.

- Government procurement of advanced technology products: as indicated in the European Innovation Scoreboard «The indicator measures the extent to which government procurement decisions in a country foster technological innovation by providing the average response to the following question: “Government purchase decisions for the procurement of advanced technology products are (1 = based solely on price, 7 = based on technical performance and innovativeness)” (Hollanders, 2017). There is a positive relationship between the “Government procurement of advanced technology and GDP” and innovation linkages. This means that if government can demand high tech products and services to the industrial system then firms are more incentivized to cooperate and to promote a deeper public-private partnership. In effect to create high-tech products and services SMEs need to cooperative and to have a complex portfolio based either on public or on private funding. The demand of government for advanced technology create in the market an incentive to cooperation and collaboration, since innovative SMEs, startups and newcos, can better satisfy the need for high-tech products and services through the development of corporate linkages.

- Finance and support: the variable is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard as the sum of […] two indicators and measures the availability of finance for innovation projects by Venture capital expenditures, and the support of governments for research and innovation activities by R&D expenditures in universities and government research organisations (Hollanders, 2017).

There is a positive relationship between “Finance and Support” and “Innovation Linkages”. The greater the private and public financial investment in innovation and Research and Development, the greater the ability of firms (Laureti, Costantiello & Leogrande, 2020) to cooperate actively in the promotion of high-tech products and services. The finance-innovation nexus creates the condition for firms to promote deeper collaborations among SMEs designing a new scenario to develop strategic alliances able to sustain technological innovation based on Research and Development.

- Firm investments: is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard as a variable that […] includes three indicators of both R&D and non-R&D investments that firms make to generate innovations, and the efforts enterprises make to upgrade the ICT skills of their personnel (Hollanders, 2017). The greater the investment that firms realize in innovation, the greater the level of collaboration among SMEs to promote new technological products and services based on Research and Development. Generally, the ability of firm to invest depends not only on the individual condition of a certain SME in which the CEO has a positive expectation about the future of the company but, at the contrary, depends also from the social, cultural and political environment. Certainly, the presence of well-established relationships of cooperation and collaboration among firms in a context of public-private partnership can improve the trust of innovative entrepreneurs in the future improving the level of investments.

- Human resources: is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard as the […] dimension includes three indicators and measures the availability of a high-skilled and educated workforce. Human resources capture new doctorate graduates, Population aged 25-34 with completed tertiary education, and Population aged 25-64 involved in education and training.

Hollanders (2017), the greater the level of human resources the deeper the level of cooperation that SMEs realize to promote new products and services. Human resources are also able to promote a public and private partnership able to generate innovation based on Research and Development. The linkages among SMEs and between private and public organizations are deepened by the presence of high skilled human resources. Human resources in the context of innovative SMEs tend to operate has connectors able to create networks based on skills and competences creating relationships among different newcos and startups and with the involvement of public institutions.

We found that Linkages is negatively associated to:

- Population density: is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard as the « […] people per sq. km of land area (Hollanders, 2017). There is negative relationship between the “Population Density” and the “Innovation Linkages”. This negative relationship can be since generally SMEs are not present in high urbanized places such as city centers. Effectively, high tech industries tend to be located far from urban centers, in small communities or in the peripheries or in city with low population density. In effect the high skilled human capital tend to prefer small towns that are more quietly in respect to city centers either for motivations that are connected to the necessity of creativity in the development of new technologies and inventions, either for questions related to the costs of assets that are lower in centers with low population density. The increase in the population density reduces the level of innovation linkages.

- Employment share Services: is defined by the European Innovation Scoreboard as the « Average percentage share of Employment in Services for the years 2015-2017 (Hollanders, 2017). There is a negative relationship between the presence of employment in the service sector and the presence of innovation linkages among SMEs and in the context of public-private partnerships. Specifically, the negative relationship can be better understood considering that process innovations are more connected to services. Even if in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is not possible to distinguish between products and services, since both can be considered in the general classification of products, then product innovation tends to have a greater impact on employment, exportation, and economic growth (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2020). On the other side process innovation is associated to lower level of employment in respect to product innovation. Due to these differences, it is possible that SMEs that operate in service sectors are more interested in process innovation and develop a deeper competitive behavior less oriented to cooperation and collaboration in respect to SMEs that promote product innovations.

The estimated model offers some insides of the economic, financial, and cultural determinants of the Linkages among SMEs to promote innovation and either on the relevance of the public-private partnership. The degree of innovation that is present in a certain country requires the participation and the cooperation of multiple organizations and institutions. In this sense countries that are more able to develop linkages and cooperation among SMEs and that are capable to promote deeper private-public partnerships also have greatest probabilities to generate innovation.

Conclusion

In this article we have investigate the determinants of the Innovation Linkages in Europe. We consider the relevance of cooperation, collaboration, and the development of relationships at firm level. These considerations are ancient in the history of economic though and can be reconnected to the scientific work of Alfred Marshall with the idea of industrial districts. Also, we consider the role of the Italian economist Becattini in giving a new light to the Marshallian’s idea of industrial districts and the new relevance that these organizations and institutions have acquired in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution since artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data have strengthened the relationships among SMEs, startups and newcos in the creating of innovation through the sharing of knowledge. Finally, we consider the question of the networks of knowledge, the question of the proximity of firms and countries as an essential condition to promote innovation, and the tendencies of firms to be concentrated in a certain physical space.

To investigate the determinant of the innovation linkages in Europe we use data from the European Innovation Scoreboard of the European Commission in the period 2000-2019 for 36 countries. We u Data are analyzed using Panel Data with Fixed Effects, Random Effects, Dynamic Panel at 1 Stage, Dynamic Panel at 2 Stage, Pooled OLS, WLS. Results show that the Innovation Linkages in Europe is positively associated with “Buyer Sophistication”, “Government Procurement of Advanced Technology Products”, “Finance and Support”, “Firm Investments”, “Human Resources”, and negatively associated with “Population Density”, “Employment Share Services”. Our results show that if policy makers are interested in promoting a deeper cooperation among SMEs then they should invest in creating a cultural and economic environment that is positively oriented to high-technology products and services.

References

Abramo, G., D?Angelo, C., & Solazzi, M. (2010). Assessing public?private research collaboration: Is it possible to compare university performance. Scientometrics, 84(1), 173-197.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Arrow, K.J. (1971). The economic implications of learning by doing in readings in the theory of growth, London. Palgrave Macmillan, 131-149.

Bahar, D., Hausmann, R., & Hidalgo, C.A. (2014). Neighbors and the evolution of the comparative advantage of nations: Evidence of international knowledge diffusion?Journal of International Economics, 92(1), 111-123.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Balland, P.A., Jara-Figueroa, C., Petralia, S.G., Steijn, M.P., Rigby, D.L., & Hidalgo, C.A. (2020). Complex economic activities concentrate in large cities. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(3), 248-254.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Becattini, G. (2002). Industrial sectors and industrial districts: Tools for industrial analysis. European planning studies, 10(4), 483-493.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Becattini, G. (2004). Industrial districts: A new approach to industrial change. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bigliardi, B., & Galati, F. (2016). Which factors hinder the adoption of open innovation in SMEs?Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(8), 869-885.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bondonio, D., Biagi, F., & Stancik, J. (2016). Counterfactual impact evaluation of public funding of innovation, investment and R&D. Joint Research Centre, JRC99564.

Bye, B.K.M., & Raknerud, A. (2019). The impact of public R&D support on firms' patenting. Discussion Papers, 911.

Casals, F.E. (2011). The SME co-operation framework: A multi-method secondary research approach to SME collaboration. 2010 International Conference on E-business, Management and Economics IPEDR, 31, 118-124.

Chybowska, D., Chybowski, L., & Souchkov, V. (2018). R&D in Poland: Is the country close to a knowledge- driven economy?Management Systems in Production Engineering, 26(2), 99-105.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Costantiello, A., & Leogrande, A. (2020). The innovation-employment nexus in Europe. American Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 4, 166-187.

Crespi, G., Garone, L.F., Maffioli, A., & Stein, E. (2020). Public support to R&D, productivity, and spillover effects: Firm-level evidence from Chile. World Development, 130.

De Marco, C.E., Martelli, I., & Di Minin, A. (2020). European SMEs? engagement in open innovation: When the important thing is to win and not just to participate, what should innovation policy do?Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152.

Hidalgo, C. (2015). Why information grows: The evolution of order, from atoms to economies. Basic books.

Hidalgo, C.A., Balland, P.A., Boschma, R., Delgado, F.M., & Zhu, K.S. (2018). The principle of relatedness. International conference on complex systems, 451-457.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hollanders, H., Es-Sadki, N., Vertesy, D., & Damioli, G. (2017). European Innovation Scoreboard 2017? Methodology Report, European Commission.

Lam, J.C.K., Hills, P., & Ng, C.K. (2013). Open innovation: A study of industry-university collaboration in environmental R&D in Hong Kong. International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Soc

Laureti, L., Costantiello, A., & Leogrande, A. (2020). The Finance-Innovation Nexus in Europe. IJISET - International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, 7(2), 11-55.

Leckel, A., Veilleux, S., & Dana, L.P. (2020). Local open innovation: A means for public policy to increase collaboration for innovation in SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 153.

Marshall, A. (1920). Industry and trade: A study of industrial technique and business organization and of their influences on the conditions of various classes and nations, Macmillian.

Martinez-Costa, M., Jimenez-Jimenez, D., & Dine-Rabeh, H.A. (2019). The effect of organisational learning on interorganisational collaborations in innovation: An empirical study in SMEs. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 17(2), 137-150.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Padilla-Melendez, A., Del Aguila-Obra, A.R., & Lockett, N. (2013). Shifting sands: Regional perspectives on the role of social capital in supporting open innovation through knowledge transfer and exchange with small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), 296-318.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Ple?niarska, A. (2018). The intensity of university-business collaboration in the EU. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis Economic Papers, 6(339), 147-160.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Polanyi, M. (2009). The tacit dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Raudla, R., Karo, E., Valdmaa, K., & Kattel, R. (2015). Implications of project-based funding of research on budgeting and financial management in public universities. Higher Education, 70(6), 957- 971.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Romer, P.M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic perspectives, 8(1), 3-22.

Sag, S., Sezen, B., & Guzel, M. (2016). Factors that motivate or prevent adoption of open innovation by SMEs in developing countries and policy suggestions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 756-763.

Schumpeter, J.A., & Opie, R. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books.

Schuurman, D., Baccarne, B., Marez, L.D., Veeckman, C., & Ballon, P. (2016). Living labs as open innovation systems for knowledge exchange: Solutions for sustainable innovation development. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 10(2-3), 322-340.

Siripitakchai, N., & Miyazaki, K. (2015). University-Industry Linkages (UILs) and Research collaborations: Case of Thailand?s National Research Universities (NRUs). In Industrial Engineering, Management Science and Applications 2015, 189-198.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Solow, R.M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The quarterly journal of economics, 70(1), 65-94.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Theyel, N. (2013). Extending open innovation throughout the value chain by small and medium-sized manufacturers. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), 256-274.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Waltermann, M., Wolff, G., & Rank, O. (2019). Formal and informal cross-cluster networks and the role of funding: A multi-level network analysis of the collaboration among publicly and privately funded cluster organizations and their managers. Social Networks, 58, 116-127.

Zygmunt, A. (2019). External linkages and intellectual assets as indicators of firms? Innovation activities: Results from the Czech Republic and Poland. Copernican economy, 10(2), 291-308.

Received: 28-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. IJE-21-10111; Editor assigned: 30-Dec-2021, PreQC No. IJE-21-10111(PQ); Reviewed: 07-Jan-2022, QC No. IJE-21-10111; Revised: 19-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. IJE-21-10111(R); Published: 28-Jan-2022