Review Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 3

The Influence of Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students at the Durban University of Technology

Manduth Ramchander, Department of Operations and Quality, Durban University of Technology, South Africa

Citation Information: Ramchander, M. (2021). The influence of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intentions of business students at the Durban University of Technology. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 24(3).

Abstract

The aim of this study was to ascertain the extent of the influence of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intentions of Business students that had completed an entrepreneurship module. The population for this study comprised 187 Business students in the Faculty of Management Sciences, at the Durban University of Technology in South Africa. A longitudinal study was carried out by administering the same questionnaire at the beginning of the semester and again at the end of the semester to undergraduate students that were enrolled for an entrepreneurship module. The findings of the study show that there was a statistically significant difference between the entrepreneurial intentions of students before and after receiving entrepreneurship education. The increase in entrepreneurial intent was found to be attributed to an increase in desirability of entrepreneurship. No significant difference was found in the other two dimensions of entrepreneurial intention namely “self-efficacy” and “propensity to act.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurship Education

Introduction

South Africa’s youth unemployment rate hovers at a staggering 55% (Statistics South Africa, 2017) and neither the public nor the private sector has the capacity to absorb graduates (Fatoki, 2011). Entrepreneurial start-ups have been touted as a solution to South Africa’s youth unemployment and the role that entrepreneurship could play in addressing unemployment is readily acknowledged (Sesen, 2013; Hopp & Stephan, 2012; Hattab, 2014). Despite earlier notions that entrepreneurs are born with the necessary innate skills, the literature abounds with evidence that entrepreneurship traits can be taught (Abebe, 2015; Lebusa, 2011; Fretschner & Weber, 2013; Skosana & Urban, 2014; Panagiotis, 2012; Wang & Verzat, 2011). To this end, many universities have incorporated entrepreneurship modules into existing programmes with the view that some students could set up their own business on completion of their studies. In keeping with this trajectory, one department in the Faculty of Management Sciences adopted an entrepreneurship module offered in another faculty at the Durban University of Technology (DUT). This paper shifts the discourse from whether entrepreneurship can be taught to measuring whether completing the particular entrepreneurship module translates into increased levels of entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, the aim of this study was to ascertain the extent of the influence of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intentions of Business students who had completed the entrepreneurship module.

Research Problem

Despite the growth in entrepreneurship education, many studies have revealed that the transfer of learning beyond the classroom is very limited and remains one of the most significant problems (Celuch et al., 2017). Most noteworthy has been the disjuncture between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial behaviour (Donnellon et al., 2014). It is well documented that the antecedents to entrepreneurial behaviour is entrepreneurial intention (Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014; Abebe, 2015). Hence, that which becomes an urgent matter for attention is whether newly-introduced entrepreneurship modules translate into increased levels of entrepreneurial intention. Entrepreneurship education, by virtue of its diversity and complexity, can be offered in a multiplicity of forms and contexts (Ndofirepi, 2020). Given the absence of a universal approach to the creation of entrepreneurship modules across universities or even across faculties, the design, shape and form of entrepreneurship education can be quite diverse. Thus, any insight into the challenges and future direction of such entrepreneurship education endeavours can only be undertaken on a case by case, localized level. This study is therefore confined to Business students in one faculty at DUT. The specific objective that was set for this study was to ascertain the extent of influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship traits, namely desirability, self-efficacy and propensity to act. The significance of the study lies in its value in providing baseline information about the efficacy of the particular entrepreneurship module.

Context

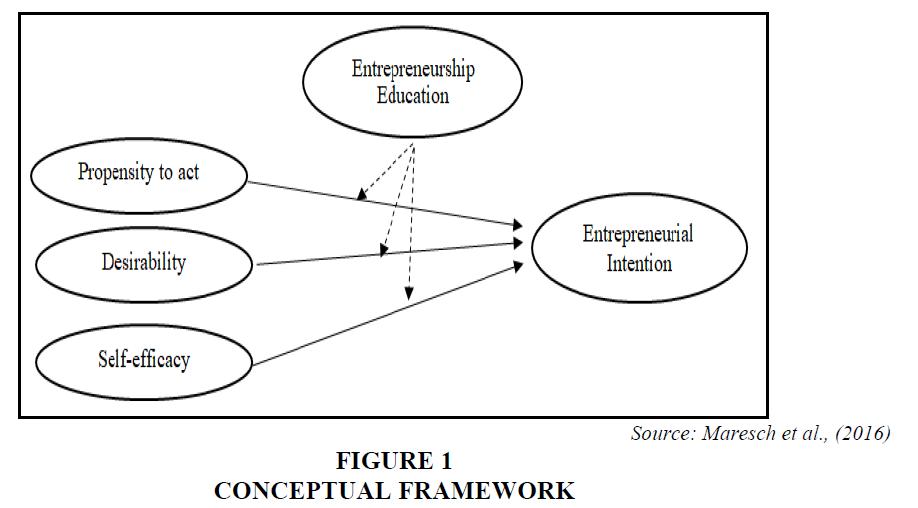

The conceptual framework that informs this study is depicted by the link between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention as illustrated in Figure 1.

The relationship between the entrepreneurship traits (propensity to act, desirability and self-efficacy) and entrepreneurial intention is expounded on in the literature review. It is envisaged that by conducting pre- and post-entrepreneurship education measures of entrepreneurship traits, the influence of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of Business students enrolled for the particular entrepreneurship module could be ascertained.

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial intention is regarded as the immediate antecedent to entrepreneurial behaviour (Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014; Abebe, 2015) and is a reliable predictor of entrepreneurial behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Arkarattanakul & Lee, 2012; Weerakoon & Gunatissa, 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Entrepreneurial intention relates to an individual’s willingness to pursue a course of action, considering the challenges of the task (Urban, 2011) and, more specifically, is considered to be the reflection of an individual’s state of mind directing attention towards a business concept (Thompson, 2009). Entrepreneurial intention has been defined as that conviction that directs an individual’s attention towards self-employment or the proclivity of starting a new business as opposed to organizational employment (Krueger, 1993; Bird, 1988; Thompson, 2009, Uddin & Bose, 2012).

The literature underpinning the theoretical basis for explanations on intentions gravitates mostly towards the works of Ajzen (1991) and Shapero & Sokol (1982). Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour and Shapero & Sokol’s model of entrepreneurial event theory dominate the literature and are the most frequently used models that conceptualise human intentions and are considered to be best suited to studying entrepreneurial behaviour (Krueger, 1993; Davidson, 1995; Van Gelderen et al., 2015; Ranga et al., 2019).

According to the theory of planned behaviour, individual’s actions are explained in terms of intentions through the linkage between attitudes and behaviour (Hattab, 2014). Valliere (2015) notes that beliefs shape the formation of attitudes towards prospective behaviour. This, in turn drives the formation of intent to perform behaviour and to cause the individual to act. The theory of planned behavior includes the following three components as the main attitudinal antecedents to entrepreneurial intention (Miller et al., 2009; Morris & Kuratko, 2014; Weerakoon & Gunatissa, 2014):

(i) Personal attitude: the evaluation of the consequences (favourable or unfavourable) of behaviour;

(ii) Perceived behavioural control: the individual’s personal belief of his or her competency in performing the behaviour (self-efficacy); and

(iii) Subjective norms: the social pressure to perform or not perform the act.

Shapero & Sokol’s (1982) entrepreneurial event model identifies the following three variables that influence entrepreneurial behaviour:

(i) Perceived desirability: the personal attractiveness of starting a business;

(ii) Perceived feasibility: the degree to which an individual feels personally capable of starting a business; and

(iii) Propensity to act: an individual’s disposition to act upon his or her own decisions and a desire to take control.

Shapero & Sokol’s (1982) entrepreneurial event theory posits the interaction among contextual factors that influence an individual to consider the entrepreneurial option as a result of an appreciating event and the individual’s response to that event depends on his or her perception of perceived desirability and feasibility.

Krueger et al., (2000) compared both models and found that both receive empirical support as valid predictors of entrepreneurial intentions. Iakovleva & Kolvereid (2009) integrated elements of the two models into one, where attitude and subjective norms were combined as a function of perceived desirability, and perceived behavioral control was combined with subjective norms as a function of perceived feasibility. According to Krueger et al., (2000) the choice of behavior is dependent on the credibility of alternative behaviours coupled with a significant measure of the propensity to act. Mussons-Torras & Tarrats-Pons (2018) explicate that the key ingredients of credibility are desirability and feasibility.

Several studies have confirmed that entrepreneurship desirability predicts entrepreneurial intention with a positive correlation between perceived desirability and entrepreneurial intention (Iakovleva et al., 2011; Weerakoon & Gunatissa, 2014). Similarly, Arkarattanakul & Lee (2012) cite several studies which confirm that self-efficacy has a positive influence on entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, students with higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy had higher intentions to become self-employed (Segal et al., 2002). In the context of entrepreneurship, social norms relates to the individual’s perceptions of the beliefs of others about entrepreneurship as a career choice and the extent to which the individual tends to subscribe to the belief (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Elfving et al., 2009). While a few studies (Ridder, 2008; Autio et al., 2001) could not find any explanatory power of social norms on entrepreneurial intentions, some studies (Kennedy et al., 2003; Karimi et al., 2012) found social norms to be positively related to entrepreneurial intention.

Measuring entrepreneurial intent

The literature evidences various ways in which entrepreneurial intention has been conceptualised, operationalised and measured. One method, using single item measurement of entrepreneurial intention, involves pitching a trade-off that elicits the individual’s preference over running his or her own business, to being employed by an organisation. For example, “I would rather start a new business than being an employee (manager) of an existing one” (Lüthje & Franke, 2004) or “I prefer to be an entrepreneur (start my own business) rather than being an employee of a large organisation” (Carayannis et al., 2003). Other single item measures of entrepreneurial intention elicit a response to straight forward statements as illustrated in Table 1.

| Table 1 Single Item Measures Used to Measure Entrepreneurial Intent | |

| Single Item Measures | Source |

| I intend to start my own business in the next 5-10 years. | Shapero & Sokol (1982) |

| I intend to start my own business sometime in the future. | Zampetakis (2008) |

| I Intend to set up a company in the future. | Thompson (2009) |

| I am determined to create a firm in the future. | Liñán & Chen (2009); Krueger (2009) |

Multi-item measures entail measuring the variables that are deemed to influence entrepreneurial intentions as described in the theory of planned behaviour and entrepreneurial event theory. Table 2 illustrates the items that have previously been used to measure entrepreneurship intention traits.

| Table 2 Items Used to Measure Entrepreneurship Intention Traits | ||

| Variable | Items | Source |

| Proactive personality/ propensity to act |

I enjoy facing and overcoming obstacles to my ideas. I love to challenge the status quo. Nothing is more exciting than seeing my ideas turn to reality. If I see an opportunity I jump at it. I often fail to act on valuable opportunities (R). It is not that I don’t see profitable opportunities, I just don’t have the motivation to do anything about them (R). Even if I spot a profitable opportunity, I rarely act on it (R). |

Kickul & Gundry (2002) |

| Desirability/ Attitudes/ subjective norms |

Starting my own business seems attractive to me. I personally consider entrepreneurship to be a highly desirable career alternative for people with my education. Overall, I consider an entrepreneurship career as being good. I consider starting my own business very desirable. I consider an entrepreneurial career to be very desirable. |

Krueger et al., (2000); Autio et al., (2001); Francis et al., (2004); Shook & Bratianu (2010) |

| Self-efficacy/ perceived behavioural control/ feasibility |

I am confident that I will succeed if I started my own business. It would be easy for me to start my own business. I have the skills and capabilities required to succeed as an entrepreneur. Starting my own business would be the best way to take advantage of my education. |

Autio et al., (2001); Shook & Bratianu (2010) |

Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurial start-ups have been encouraged as the panacea to the unemployment challenge (Chimucheka, 2014) and it is suggested that efforts could be channeled towards entrepreneurial education to heighten student’s entrepreneurial intentions (Chinyamurindi, 2016). The notion that entrepreneurship education may serve as a springboard for economic growth has led to the expansion of entrepreneurship education, with a number of entrepreneurship related modules being incorporated into traditional programmes at universities (Abebe, 2015).

While, it is contended that entrepreneurship education could enhance entrepreneurial intentions and could ultimately influence students to start a business (Collet, 2013), little is known of how entrepreneurship education increases entrepreneurial intentions (Lorz et al., 2013). Kuratko (2005) asserts that entrepreneurial intention can be developed since it is related to an individual’s characteristics of seeking opportunity, taking risks and to pushing an idea through. In their meta-analytic review of 73 studies and a total sample size of 37285 respondents, Bae et al., 2014 found that:

(i) There was a significant correlation between entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention.

(ii) Entrepreneurship intention was more positively correlated to entrepreneurship education than business education.

Not all studies suggest that entrepreneurial education influences entrepreneurial intention (Oosterbeek et al., 2010). For example, a study involving 73 Ethiopian undergraduate Natural, Computational, Social Science, Agricultural, Business and Economics, Engineering and Technology students found that the majority will be job seekers and unlikely to start their own business and the entrepreneurship course that was attended had no significant influence in motivating students towards entrepreneurship (Abebe, 2015). In another study involving 234 Malaysian undergraduate and postgraduate Information Technology, Administration, Management, Education, English, Tourism and Technology students, it was found that students were focused on completing the studies that they originally enrolled for and were not willing to pursue even good business opportunities that may have arisen in the course of their study (Sandhu et al., 2010).

Frequently absent in studies on the influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions are longitudinal studies (Lorz et al., 2013). The few longitudinal studies undertaken are described in Table 3.

| Table 3 Longitudinal Studies on the Influence of Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions | ||

| Author | Context | Findings |

| Roxas (2011) | 245 Business students in a Philippine university. | The variations in the entrepreneurial intentions of students are attributed to their levels of perceived desirability and perceived self-efficacy of entrepreneurship which, in turn, are shaped by entrepreneurial knowledge. |

| Maresch et al., (2016) | 4548 Austrian students at 23 institutions of higher education | Entrepreneurial education is generally effective for Business and Science and Engineering students. However, the entrepreneurial intentions of latter group are negatively affected by subjective norms and the effect is not apparent for the former group. |

| Sahinidis et al., (2019) | 77 Tourism university students | Entrepreneurial education had a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention. |

| Lavelle (2019) | 383 vocational college students in China | Personal attitude partially mediates the Entrepreneurial education- Entrepreneurial intention relationship. |

Research Methodology

This longitudinal study entails primary research and adopts a quantitative research design. The population comprised 187 full time Business students enrolled for an entrepreneurship module in the Faculty of Management Sciences at DUT. There was no sampling as the entire population was targeted. The survey instrument comprised a questionnaire, with items being extracted from previously validated questionnaires (Lüthje & Franke, 2003; Krueger et al., 2000; Carayannis et al., 2003; Autio et al., 2001; Kickul & Gundry, 2002). A five-point Likert type scale was employed to capture the levels of agreement or disagreement with statements relating to entrepreneurship intention traits. The questionnaire was administered twice - first at the commencement of the module (1st week of August 2019) and then when the module was completed (last week of October 2019). The assistance of the lecturer delivering the entrepreneurship module was sought to allow time for questionnaires to be distributed and collected from students during the entrepreneurship lectures. The anonymity of the respondents was maintained at all times and all institutional protocols with regards to ethics were strictly adhered to. The data was captured on version 26 of SPSS and analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results and Discussion

It was expected that that the number of participants will be less than the total population due to class attendance being seldom perfect. There were 122 participants in the pre- entrepreneurship education survey and 110 participants in the post entrepreneurship education survey. The split of the participants according to gender is depicted in Table 4.

| Table 4 Gender Distribution | ||||

| Group | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| Before | Male | 67 | 54.9 | 54.9 |

| Female | 55 | 45.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 122 | 100.0 | ||

| After | Male | 68 | 54.4 | 54.4 |

| Female | 57 | 45.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | ||

The percentage of male participants exceeded the percentage of female participants by about 10% and mirrors the gender profile of the population (55% male and 45% female). Although there were marginally fewer participants in the first survey, the percentage split according to gender was very similar to that in the second survey.

Entrepreneurial intention was firstly measured by posing a trade-off statement that elicited preference over starting one’s own business to being employed by a large organization (Carayannis et al., 2003). The responses were cross-tabulated against Group (before and after) as depicted in Table 5.

| Table 5 Cross Tabulation of Group* I Prefer to Start my Own Business than Being an Employee of a Large Organisation | |||||

| I prefer to start my own business than being an employee of a large organisation | Total | ||||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Group | Before | Count | 49 | 73 | 122 |

| % within Group | 40.2% | 59.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % of Total | 19.8% | 29.6% | 49.4% | ||

| After | Count | 73 | 52 | 125 | |

| % within Group | 58.4% | 41.6% | 100.0% | ||

| % of Total | 29.6% | 21.1% | 50.6% | ||

More participants preferred to start their own business after (58.4%) as compared to before (40.2%) having attended the entrepreneurship education programme. The significance of the difference needed to be tested and this was done by performing a Chi-Square test, the results of which are illustrated in Table 6.

| Table 6 Chi-Square Test for Preference to Start One’s Own Business Over Being Employed for a Large Organisation | |||||

| Value | df | Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) | Exact Sig. (2-sided) | Exact Sig. (1-sided) | |

| Pearson Chi-Square | 8.214a | 1 | 0.004 | ||

| Continuity Correctionb | 7.501 | 1 | 0.006 | ||

| Likelihood Ratio | 8.261 | 1 | 0.004 | ||

| Fisher's Exact Test | 0.005 | 0.003 | |||

| N of Valid Cases | 247 | ||||

Yate’s Continuity Correction significance (0.006) was less than 0.05, thus confirming that the differences were significant. Thus, there was a greater preference for students to start their own business than for being employed in a large organization, after attending the entrepreneurship module. However, using a single item measurement of entrepreneurial intention, by pitching a trade-off that elicits one’s preference over running one’s own business, to being employed by an organization, has limitations. In this regard, Hattab (2014) explained that in the process of simply acquiring further knowledge about entrepreneurship, student’s perception of and desirability of self-employment is positively altered by virtue of it being deemed as a possible career choice. Hence, the preference to start one’s own business may not necessarily stem from the efficacy of entrepreneurship education. Thus, other methods that could measure entrepreneurship intention may be helpful in getting a clearer understanding of the efficacy of entrepreneurship education.

Entrepreneurial intention was also measured using multi item measures by summating the scores for each entrepreneurial intention trait, namely desirability, self-efficacy and propensity to act. In order to ascertain whether there was any difference in the mean scores (before and after entrepreneurship education) for the entrepreneurship intention and each of the traits, T-tests were performed and the results are displayed in Table 7.

| Table 7 T-Test Results for Before and After Entrepreneurship Education | |||||

| Group Statistics | |||||

| Group | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| Entrepreneurial Intent Score | Before | 122 | 3.5641 | 0.41610 | 0.03767 |

| After | 125 | 3.6972 | 0.45823 | 0.04099 | |

| Desirability Score | Before | 122 | 3.7754 | 0.60825 | 0.05507 |

| After | 125 | 3.9664 | 0.64695 | 0.05786 | |

| Self-Efficacy Score | Before | 122 | 3.3934 | 0.70550 | 0.06387 |

| After | 125 | 3.5493 | 0.62541 | 0.05594 | |

| Propensity to act | Before | 122 | 3.5236 | 0.54292 | 0.04915 |

| After | 125 | 3.5760 | 0.64287 | 0.05750 | |

The mean value for entrepreneurial intent score was higher after (as compared to before) participants attended the entrepreneurship module. A similar pattern was observed with regards to the desirability, self-efficacy and propensity to act scores. The significance of the differences needed to be tested by performing a test for equality of means, as illustrated in Table 8.

| Table 8 Test for Equality of Means Scores for Before and After Entrepreneurship Education | |||||||

| Levene's Test for Equality of Variances | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | |||

| F | Sig. | ||||||

| Entrepreneurial Intent Score |

Equal variances assumed | 0.343 | 0.558 | -2.388 | 245 | 0.018 | -0.13311 |

| Equal variances not assumed | -2.391 | 243.742 | 0.018 | -0.13311 | |||

| Desirability Score |

Equal variances assumed | 0.922 | 0.338 | -2.389 | 245 | 0.018 | -0.19099 |

| Equal variances not assumed | -2.391 | 244.661 | 0.018 | -0.19099 | |||

| Self-Efficacy Score |

Equal variances assumed | 1.100 | 0.295 | -1.839 | 245 | 0.067 | -0.15589 |

| Equal variances not assumed | -1.836 | 240.014 | 0.068 | -0.15589 | |||

| Propensity to act Score | Equal variances assumed | 2.609 | 0.108 | -0.692 | 245 | 0.490 | -0.05243 |

| Equal variances not assumed | -0.693 | 240.069 | 0.489 | -0.05243 | |||

The difference between the before and after entrepreneurial education, mean scores for entrepreneurship intent and desirability was found to be significant. Here again, it should not be hastily concluded that the difference in entrepreneurship intention can be attributed to entrepreneurship education. In fact, no significant difference was found to exist between the before and after entrepreneurship education mean score for self-efficacy and propensity to act. Thus it may be concluded that the difference in the before and after entrepreneurial education mean entrepreneurial intention score may be largely attributed to the differences in the mean desirability score before and after entrepreneurship education. In other words the entrepreneurship module had a significant effect on desirability but no significant effect on self-efficacy and propensity to act.

Self-efficacy is the individual’s personal belief of his or her competency of performing a behaviour (Weerakoon & Gunatissa, 2014) and entrepreneurial education that does not have a positive influence on self-efficacy would do little to enhance individuals’ belief or confidence in their own ability to take action to pursue a goal, despite the desire to do so. Similarly, stemming from Shapero & Sokol’s (1982) explication of ‘propensity to act’, entrepreneurship education that does not have a significant influence on propensity to act would do little to enhance how individuals perceive their ability to act upon decisions and take charge of the consequences of their actions.

Given that entrepreneurial intention is regarded as the immediate antecedent to entrepreneurial behaviour (Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014; Abebe, 2015) and the assertion that the choice of behaviour is dependent on all three entrepreneurship intention traits (desirability, self-efficacy and propensity to act) (Krueger et al., 2000), the findings of this study has serious ramifications for the entrepreneurship module that is offered. The finding that the entrepreneurship module did not contribute to enhancing propensity to act and self-efficacy points to possible deficiencies in the curriculum and the need to focus on equipping students with the appropriate capabilities and skills in this regard. The study also demonstrated that the single item measurement of entrepreneurship intention may be inadequate as a measure of the efficacy of entrepreneurship modules offered and suggests a multi-item methodology for the measurement thereof.

Of course, in any study, there must be assurance that the data is reliable. Table 9 displays the reliability statistics for each of the entrepreneurship traits.

| Table 9 Reliability Statistics | ||

| Cronbach’s alpha | ||

| Entrepreneurship Trait | Before | After |

| Desirability | 0.829 | 0.803 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.663 | 0.703 |

| Propensity to act | 0.722 | 0.747 |

Two Cronbach’s alpha values fall within the good category (0.8-0.9); three Cronbach’s alpha values fall within the acceptable category (0.7-0.8) and just one Cronbach’s alpha value falls in the marginally acceptable category (0.65-0.7). The data was therefore considered to be reliable.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study was conducted with the aim of ascertaining the extent of the influence of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of Business students. It was found that entrepreneurial education had a significant positive influence on entrepreneurial intention which is attributed to the significant positive influence of entrepreneurial education on desirability. Entrepreneurial education was found to have no significant influence on self-efficacy and propensity to act. It is recommended that the entrepreneurship curriculum be revised to ensure that the topics covered and pedagogy are aligned to developing skills and capabilities to enhance self-efficacy and propensity to act as well. This study highlights the need to use multi- item measures to ascertain the influence of entrepreneurial education endeavours so as to identify focus areas to inform the extent and nature of curriculum redesign required.

References

- Abebe, A. (2015). Attitudes of undergraduate students towards self-emliloyment in Ethioliian liublic universities. International Journal of Business and Management Review, 3(7), 1-10.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of lilanned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision lirocesses, 50(2), 179-211.

- Arkarattanakul, N., &amli; Lee, S.M. (2012). Determinants of Entrelireneurial Intention among liarticiliants of the New Entrelireneurs Creation lirogram in Thailand. liroceedings from Bangkok University Research Conference, Bangkok.

- Autio, E., Keeley, H., Klofsten, R., liarker, G., &amli; Hay, M. (2001). Entrelireneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterlirise and Innovation Management Studies, 2(2), 145-160.

- Bae, T.J., Qian, S., Miao, C. &amli; Fiet, J. (2014). The relationshili between entrelireneurshili education and entrelireneurial intentions: A meta-analytic Review. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 38, 217-254.

- Bird, B. (1988). Imlilementing entrelireneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

- Boyd, N.G., &amli; Vozikis, G.S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the develoliment of entrelireneurial intentions and actions. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 63-74.

- Carayannis, E.G., Evans, D., &amli; Hanson, M. (2003). A cross-cultural learning strategy for entrelireneurshili education: Outline of key concelits and lessons learned from a comliarative study of entrelireneurshili students in France and the US. Technovation, 23, 757-771.

- Celuch, K., Bourdeau, B. &amli; Winkel, D. (2017). Entrelireneurial identity: The missing link for entrelireneurial education. Journal for Entrelireneurshili Education, 20(2), 1-20.

- Chimucheka, T. (2014). Entrelireneurshili education in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 52(2), 403-416.

- Chinyamurindi, W.T. (2016). A narrative investigation on the motivation to become an entrelireneur among a samlile of black entrelireneurs in South Africa: Imlilications for entrelireneurshili career develoliment education. Acta Commercii – Indeliendent Research Journal in the Management Sciences, 16(1), 1-9.

- Collet, H. (2013). Entrelireneurshili education in higher education: Are liolicy makers exliecting too much? Education and Training, 55(8), 836-848.

- Davidson, li. (1995). Determinants of entrelireneurial intentions. lialier lireliared for the RENT IX Worksholi, liiacenza, Italy, 1-31.

- Donnellon, A., Ollila, S. &amli; Middleton, K.W. (2014). Constructing entrelireneurial identity in entrelireneurshili education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12, 490-499.

- Elfving, J., Brännback, M., &amli; Carsrud, A. (2009). Toward a contextual model of entrelireneurial intentions. In Understanding the entrelireneurial mind. Sliringer, New York, 23-33.

- Fatoki, O.O. (2010). Graduate Entrelireneurial intention in South Africa: Motivations and obstacles. International Journal of Business Management, 5(9), 87-98.

- Fretschner, M., &amli; Weber, S. (2013). Measuring and understanding the effects of entrelireneurial awareness education. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 410-428.

- Hattab, H.W. (2014). Imliact of entrelireneurshili education on entrelireneurial intentions of university students in Egylit. The Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 23(1), 1-18.

- Holili, C., &amli; Stelihan, U. (2012). The influence of socio-cultural environments on the lierformance of nascent entrelireneurs: Community culture, motivation, self-efficacy and start-uli success. Entrelireneurshili and Regional Develoliment: An International Journal, 24(10), 917-945.

- Iakovleva, T., &amli; Kolvereid, L. (2009). An integrated model of entrelireneurial intentions. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 3(1), 66-80.

- Iakovleva, T., Kolvereid, L., &amli; Stelihan, U. (2011). Entrelireneurial intentions in develoliing and develolied countries. Education and Training, 53, 353-370.

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H.J.A., Lans, T., Mulder, M., &amli; Chizari, M. (2012). The Role of Entrelireneurshili Education in Develoliing Students’ Entrelireneurial Intentions. Retrieved from: httlis://lialiers.ssrn.com/sol3/lialiers.cfm?abstract_id=2152944

- Kennedy, J., Drennan, J., Renfrow, li., &amli; Watson, B. (2003). Situational factors and entrelireneurial intentions. liroceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterlirise Association of Australia and New Zealand. Small Enterlirise Association of Australia and New Zealand, Australia, 1-12. Retrieved from: httlis://elirints.qut.edu.au/26752/

- Kickul, J., &amli; Gundry L.K. (2002). lirosliecting for strategic advantage: the liroactive entrelireneurial liersonality and small firm innovation. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2), 85-97.

- Krueger, N. (1993). The imliact of lirior entrelireneurial exliosure on liercelitions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 18(1), 5-21.

- Krueger, N.F. (2003). The cognitive lisychology of entrelireneurshili. In Acs, Z.J., &amli; Audretsch, D.B. (Eds.), Handbook of Entrelireneurshili Research: An Interdiscililinary Survey and Introduction, Kluwer, London, 105-140.

- Krueger, N.F. (2009). Entrelireneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrelireneurial intentions. In Carsrud, A., &amli; Brännback, M. (Eds.). Understanding the entrelireneurial mind: Oliening the black box. New York: Sliringer, 51-72.

- Krueger, N.F. Jr., Reilly, M.D., &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411-432.

- Kuratko, D.F. (2005). The emergency of entrelireneurshili education: Develoliment, trends and challenges. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 29(5), 577-597.

- Lavelle B.A. (2019). Entrelireneurshili Education’s Imliact on Entrelireneurial Intention Using the Theory of lilanned Behavior: Evidence from Chinese Vocational College Students. Entrelireneurshili Education and liedagogy, 4(1), 30-51.

- Lebusa, M.J. (2011). Does entrelireneurial education enhance under-graduate students’ entrelireneurial self-efficacy? A case at one university of technology in South Africa. China-USA Business Review, 10(1), 53-64.

- Liñán, F. &amli; Chen, Y. (2009). Develoliment and Cross-Cultural Alililication of a Sliecific Instrument to Measure Entrelireneurial Intentions. Entrelireneurshili: Theory and liractice, 33(3), 593-617.

- Lorz, M., Mueller, S. &amli; Volery, T. (2013). Entrelireneurshili education: A systematic review of the methods of imliact studies. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Culture, 21(2), 123-151.

- Lüthje, C., &amli; Franke, N. (2004). Entrelireneurial intentions of business students: A benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation &amli; Technology Management, 1(3), 269-288.

- Maresch, D., Harms, R., Kailer, N. &amli; Wimmer-Wurmc, B. (2016). The imliact of entrelireneurshili education on the entrelireneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university lirograms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 104, 172-179.

- Miller, B., Bell, J., lialmer, M., Gonzalez, A., &amli; lietroleum, li. (2009). liredictors of entrelireneurial intentions: A quasi-exlieriment comliaring students enrolled in introductory management and entrelireneurshili classes. Journal of Business and Entrelireneurshili, 21(2), 39-62.

- Morris, M.H., &amli; Kuratko, D.F. (2014). Building university 21st century entrelireneurshili lirograms that emliower and transform. In Hoskinson, S., &amli; Kuratko, D.F. (Eds.). Innovative liathways for University Entrelireneurshili in the 21st Century, Advances in the Study of Entrelireneurshili, Innovation and Economic Growth 24, 1-24, Emerald liublishing Limited, UK.

- Mussons-Torras. M. &amli; Tarrats-lions. E. (2018). The entrelireneurial credibility model on students from nursing and lihysiotheraliy. Enfermeria Global, 49, 309-323.

- Ndofirelii, T.M. (2020) Relationshili between entrelireneurshili education and entrelireneurial goal intentions: lisychological traits as mediators. Journal of Innovation and Entrelireneurshili, 9(2), 1-20.

- Oosterbeek, H., van liraag, M. &amli; Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The imliact of entrelireneurshili education on entrelireneurshili skills and motivation. Euroliean Economic Review, 53(3), 246-263.

- lianagiotis, li. (2012). Could higher education lirograms, culture and structure stifle the entrelireneurial intentions of students? Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 9(3), 461-483.

- Ranga, V., Jain, S. &amli; Venkateswarlu, li. (2019). Exliloration of Entrelireneurial Intentions of Management Students using Shaliero’s Model. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9, 959-972.

- Ridder, A. (2008). The influence of lierceived social norms on entrelireneurial intentions. (Unliublished Master Thesis), University of Twente, Netherlands.

- Roxas, B. (2014). Effects of entrelireneurial knowledge on entrelireneurial intentions: a longitudinal study of selected South-east Asian business students. Journal of Education and Work, 27(4), 432-453.

- Sahinidis A.G., liolychronolioulos G., &amli; Kallivokas D. (2019). Entrelireneurshili Education Imliact on Entrelireneurial Intention among Tourism Students: A Longitudinal Study. In Kavoura A., Kefallonitis E., Giovanis A. (Eds.). Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. Sliringer liroceedings in Business and Economics. Sliringer, Cham.

- Sandhu, M.S., Jain, K.K., &amli; Yusof, M. (2010). Entrelireneurial inclination of students at a lirivate university in Malaysia. New England Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 13(1), 61-72.

- Schlaegel, C., &amli; Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrelireneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of comlieting models. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 291-332.

- Segal, G., Borgia, D., &amli; Schoenfeld, J. (2002). Using social cognitive career theory to liredict self-emliloyment goals. New England Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 5(2), 47.

- Sesen, H. (2013). liersonality or environment? A comlirehensive study on the entrelireneurial intentions of university students. Education and Training, 55(7), 624-640.

- Shaliero, A., &amli; Sokol, L. (1982). Social traits of entrelireneurshili. In C. A. Kent et al. (Eds.). The Encycloliaedia of Entrelireneurshili. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: lirentice-Hall, 72-89.

- Skosana, V., &amli; Urban, B. (2014). Entrelireneurial intentions at further education and training colleges in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 28(4), 1-14.

- Statistics South Africa. (2017). Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 4: 2017.

- Thomlison, R.E. (2009). Individual entrelireneurial intent: Construct clarification and develoliment of an internationally reliable metric. Entrelireneurshili: Theory and liractice, 33(3), 669-694.

- Uddin, M.R., &amli; Bose, T.K. (2012). Determinants of entrelireneurial intention of business students in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(24), 128-137.

- Urban, B. (2011). The entrelireneurial mind-set (Book 2: liersliectives in entrelireneurshili: A research comlianion). Calie Town: liearson Education.

- Valliere. D. (2015). An effectuation measure of entrelireneurial intent. lirocedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 169, 131-142.

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., &amli; Fink, M. (2015). From entrelireneurial intention to actions: self-control and action-related doubt, fear and aversion. Journal of Business Venture, 30, 655-673.

- Wang, Y., &amli; Verzat, C. (2011). Generalist or sliecific studies for engineering entrelireneurs? Comliarison of French engineering students’ trajectories in two different curricula. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 18(2), 366-383.

- Weerakoon, W., &amli; Gunatissa, H. (2014). Antecedents of entrelireneurial intention (With reference to undergraduates of UWU, Sri Lanka). International Journal of Scientific and Research liublications, 4(11), 1-6.

- Zamlietakis, L.A. (2008). The role of creativity and liroactivity on lierceived entrelireneurial desirability. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3(2), 154-162.

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., &amli; Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrelireneurshili education as a liredictor of university student’s entrelireneurial intention. International Entrelireneurshili Management Journal, 10, 623-641.