Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 3

The Importance of Personal Branding in an Election Campaign: The Case of the Presidential Elections

Khouloud Hammami, University of Carthage

Senda Baghdadi, University of Carthage

Citation Information: Hammami, K., & Baghdadi, S. (2024). The importance of personal branding in an election campaign: the case of the presidential elections. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(3), 1-17.

Abstract

Nowadays, personal branding is very important in an election campaign. It allows positioning and differentiation from other candidates. Political branding has developed considerably in recent years since the seminal work to become a distinct area of research within the field of political marketing. On this observation, we will present, first, the concepts of personal brand in general and in politics in particular. Second, the elements that influence the construction of personal brand. Third, the authors explore the field through qualitative studies with experts and presidential candidates in order to present a synthesis of key concepts and recommendations for a successful presidential campaign.

Keywords

Political Personal Brand, Political Marketing, Identity, Positioning, Image, Elections, Presidential Campaigns.

Introduction

Political branding (Pich and Newman, 2019) is a recent research topic in political marketing (Speed et al., 2015; Marland and De Cillia, 2020). This concept can be defined as the application of traditional commercial branding strategies, theories and frameworks in the political domain. The goal is to differentiate oneself from political competitors and identify oneself in the minds of citizens and political entities (Harris and Lock, 2010; Needham and Smith, 2015; Antoniades, 2020; Nai and Maier, 2020; Pich and Armannsdottir, 2021, 2022; Plescia et al., 2021). Thus, with the evolution of this conceptin practice and theory, different political organizations and individuals are now commonly conceptualized as political brands (Smith and French, 2009; Scammell, 2015; Simons, 2019; Nai, et al., 2019; Nai and Martinez, 2020; Pich, 2022).

However, while research on political brands is evolving, concerns have been raised in the field. For example, the direct application of commercial marketing concepts in the political context is not appropriate (Smith and French, 2009; Cwalina and al., 2015). In the literature review, it seems that there are still not enough models or frameworks for political brands to manage their identities, images, reputations or positioning in order to create and develop their political brands (Billard, 2018; Nai & Martinez I Coma, 2019; Marland & Wagner, 2019).

Thus, this research makes five main contributions. First, we present the concept of personal branding and its issues, in general and in the political domain in particular. Second, based on the theory, the authors will study the electoral context and the different specificities of the Tunisian political scene after the revolution. Third, the factors affecting the construction of a personal brand. Fourth, the authors will present the process of creating a personal brand and its importance for a presidential candidate. Fifth, we will present a synthesis of key concepts and recommendations for a successful presidential campaign.

Literature Review

Personal Brand

The concept of personal brand, although new, is a concept studied in several areas such in sports and entrepreneurship (Grzesiak, Mateusz, Grzesiak, and Barlow, 2018; Bruno and Rodrigues, 2019; Te'eni-Harari; Bareket-Bojmel, 2021; Korzh and Estima, 2022).

Indeed, the concept of branding has given spirit and soul to the robotic price-value transaction. The emergence of the Internet has required individuals, entrepreneurs and companies to be creative in communicating their public images (Lee and Chen, 2015; Creely and Henriksen, 2019; Costa and Hallmann, 2022). This technological evolution has induced the individualization of the concept of the brand, which has given birth to the personal brand, a brand uniquely attached to a person or a personality (Johnson, 2017; Confente and Kucharska, 2021). In this regard, the personal brand is the combination of expectations and perceptions that are created by the audience with the character.

Traditionally, the concept of personal brand was about celebrities, politicians or professional women who aim to succeed in their careers (Tarnovskaya, 2017). Today, the means of communication are available for everyone, which has allowed people to have their own unique personal brands on the identity, qualities of the person himself and his authenticity.

Developing a personal brand plays an important role in a person’s career and stems from people’s natural need to improve and develop themselves. However, Peters (1997) cited the term “personal branding” for the first time in his article entitled “the brand called you”. “To be in business today, our most important job is to be the chief marketer of the brand called you”.

According to McNally and Speak (2002), “how others see you” is the main element of a personal brand. In that respect, they proposed a model where personal brand is similar to the image perceived by the environment. The researchers consider that personal brand is based on three interrelated dimensions, namely competence, personal norms and style.

Runebjörk (2004) defines personal brand and its associated values as the perception of an individual’s environment. The author considers that personal brand is not something that the person does or possesses, but everything an individual does that influences the image (Simon, 2016, 2019) that the environment perceives of him or her as a brand. In other terms, a person must pay constant attention to how they behave in order to present themselves as a unique personal brand.

Gandini (2016) presents the personal brand as the fusion of what the person wants to project to the target audience (desired identity) and how the audience perceives it (perceived image) (Agnoletti 2017). According to this author, for a personal brand to be well constructed, the brand identity must be established and perceived by the audience. According to Manai and Holmlund (2015) "a personal brand consists of three elements: A core identity (personality, values, principles, education, and experiences), an extended identity (capability level, attitudes and culture), and a value proposition (functional, emotional and relational). The concept of personal branding has also been defined "as a conscious or unconscious process that aims to influence the way a person perceives another person, object, or event through the regulation and control of information during social interaction" (Thompson-Whiteside et al. 2018).

Political Personal Brand

Personalization in politics has been around decades. Indeed, researchers consider that the political arena, for example in elections, is moving from an era of party-based political communication to an era of politician-centric media coverage (Niculae et al., 2015; Van Der Pas and Aaldering, 2020). In this regard, several political parties and politicians seeking to differentiate themselves and influence electoral decisions (Smith 2009; Shafiee et al., 2020) have adopted the concept of the political brand.

Political brands comprise complex interrelated ideological and institutional components that are presented through the personal characteristics of politicians. This complexity makes the balance between constancy and renewal difficult as the primary objective is to generate public loyalty. The personified representation of political components has fostered this loyalty and has made the political domain less complex for the public; hence the importance of the concept of the political personal brand.

Building a political personal brand requires going through the same steps as any other brand. Thus, the identity of a political personal brand is based on values, positions, vision, ideology (Bosch, et al. 2006) and personal characteristics (Armannsdottir et al., 2019). Furthermore, Armannsdottir and al. (2019) have proven that political personal brand identity is strategically constructed by tangible dimensions such as physical appearance, style and communication tools and intangible dimensions such as lived experience, history, charisma, authenticity, apparent authority, skills and values (Gehl, 2011; Chen, 2013; Green, 2016).

In order for the political personal brand identity to be clear, consistent and successful, it must be well communicated to stakeholders. In other words, politicians use online and offline communication strategies to raise their profile and communicate their values.

Indeed, in order to create a political personal brand that is aligned with the desired identity, politicians, whether they are party leaders, legislators, parliamentarians or presidential candidates; use both traditional and digital communication strategies. In addition, researchers have explored the difficulty of separating the politician's personal brand from that of their party and consider that this alignment risks stifling the individuality of the personal brand by maintaining the message and communication of their party (Marland and Wagner 2020). Indeed, Falkowski and Jabłońska (2020), consider that successful campaign strategy must be balanced with the party's message to be relevant, clear and compelling. Thus, they argued that the framing imposed by the party is only one of the strategic factors that need to be considered when managing the personal brand, so that it can emerge with persuasive messages. Susila et al, (2019) studied young voters' perceptions of the political communication created and communicated by politicians. They found its importance in fostering trust, credibility and authenticity of political personal brands. Thus, they also confirmed the importance of signals, whether they are intangible and symbolic cues such as the way people speak or tangible cues such as physical appearance, clothing and style.

In this sense, in developing its communication strategy, the political brand is led to manage verbal and non-verbal elements to promote its image (Landtsheer, De Vries et al., 2008).

Methodology

After the revolution in Tunisia in 2011, called Arab Spring, political changes in Tunisia have emerged and we have seen, more and more interest of the people in politics. Indeed, the Tunisian of 2014 provides for the separation of powers by involving citizens through different types of elections. Thus, the Tunisian regime is a quasi-parliamentary regime where presidential elections are held by direct universal suffrage. In this type of elections, candidates present themselves personally to the electoral public, which favors the study of political personal brands, the subject of this research.

This article studies the case of the last Tunisian presidential elections (2019) in order to explore in depth the different issues of political personal branding and to provide a framework that will be useful for future research, for political advisors as well as for election candidates. In the literature review, it seemed to us that there were not yet enough models or frameworks for election candidates to follow. Candidates did not, to our knowledge, have a model that allows them to manage their identities, images, reputations and positioning. Hence the purpose of this research.

With the advent of new communication tools, the world population is more and more interested in the personal brand of politicians. The construction of a political personal brand in a presidential campaign has proven its effectiveness in several electoral contexts such as the success of Barack Obama's brand in reaching power and ensuring global visibility. This leads to the formulation of the central research question as follows:

"What are the issues of political personal branding in presidential campaigns?"

From this central question requires the answer to the following specific questions is required:

1. What is a political personal brand?

2. What are the contextual factors that influence political personal branding?

3. How do you build a political personal brand in an election campaign?

4. How does the personal brand contribute to a candidate's success in the campaign?

Research Approach

The personal brands are shaped by the individual’s personality, identity, history, experience and values and impacted by their interactions with the environment and the community in specific cultural context (Edvardsson et al., 2011). Furthermore, this work aims to explore the issues surrounding the concept of the political personal brand; hence, the use of a qualitative study is justified by the need to gather in-depth information. This need is in line with the reasons for using qualitative research presented by Pellemans (1999). In the same sense, Evrard et al. (1993) consider that exploratory studies are used to: "...determine a certain number of more precise propositions, specific hypotheses or the understanding of a phenomenon and its analysis in depth, with all its subtleties, which would not necessarily be possible with a more formalized study.

In this study, we aimed, first, to explore the contextual specificities of the 2019’s elections in Tunisia that had an intervention in the creation of the candidates’ personal brands with a first thematic study in order to have a better comprehension of the main themes discussed in the interviews (Braun and Clarke 2006). Second, we worked on understanding the way candidates created their personal brands and the issues they faced. For this, a lexical study has taken place. The thematic studies helped in understanding the different themes discussed in depth (Clarke and Braun, 2013). Moreover, the lexical study was used in order to have a better comprehension of the different sub-themes of the elements of the candidates’ personal brands.

First Study

The first study was conducted with two experts in order to present the state of play of the context of the presidential elections in Tunisia and the possibility of establishing brand strategies. This step allowed to identify the specificities of the electoral context and to complete the theoretical background that helped in the setting up of the interview guides for the second study. The interviews were semi-structured and lasted one hour. The profiles of the experts are presented in table 1.

| Table 1 Profiles of Sample 1 | ||

| Experts | Training/ Trade | Experience |

| Expert 1 | Expert in private law; Mr. Mohamed Fadhel Mahfoudh | -President of the National Bar Association between 2013 and 2016,one of the components of the national dialogue quartet that won the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for its successful mission that led to the holding of presidential and legislative elections in 2014 - Former minister in charge of relations with constitutional bodies, civil society and human rights organizations. |

| Expert 2 | Expert in geopolitics Dr.RafaaTabib |

-Academic researcher in geopolitics. - Member of the observatory of transformations in the Arab world - Expert advisor in geopolitics |

The interview with the expert in law focused mainly on the legal and political context of the 2019 presidential elections in Tunisia. Since he is a member in one of the parties that have proposed a candidate for the presidential elections, we interviewed him about the legal perception of the practice of marketing in politics in Tunisia and about his perception of the concept of political personal branding based on his experience and observations.

In the opening of the interview, the expert talked about the specificities of the political system in Tunisia by mentioning that it’s "A hybrid system between a presidential and a parliamentary one. In fact, according to the constitution, the one who has the most prerogatives and who represents the real authority is the head of the government who draws his legitimacy from the parliament, as in a parliamentary regime. However, we have a second center of gravity, the president of the republic who is elected by universal suffrage, but with rather limited prerogatives. Which counters the strong legitimacy he draws from the majority of the suffrage?” For him, this problem conducted to some contradictions in the electoral laws.

When we talked about the electoral laws in 2019 and its evolution from 2011, he mentioned some problems, which resulted some social effects. Actually, he assumed that we are in “a learning phase so we do not have an organized and well-managed political and legal context.” For the way marketing was managed by the laws, he considered that “the law was not sufficient to manage the use of marketing, which affected the equality of opportunity between candidates.” He mentioned also, “the report of the court of accounts proved some failures and violations of the law, such as financial and advertising fraud.” For him “the electoral law, concerning parties and association has to be reviewed to have more managed political marketing and communication.”

Then, we wanted to know more about the political context in these elections and his perception of the political scene that was presented. He assumed that “the political actors are still not well structured as in classical democratic schemes.” To support this opinion he mentioned that the local parties are still not able to “present different candidates for the different decision making positions in the different organs of the state.” He mentioned, as well a problem of positioning of the different parties “The parties are not yet well positioned on the political scene and have not yet built electoral bases.”

To conclude with him we asked about his perception of the impact of these specificities on the electoral public. He considered that “the lack of the democratic experience” added to the specificities already mentioned dived the choices not to be” based primarily on the programs of the candidates but rather on the side, as we say in Latin, "intuitu personae", especially that the Tunisian people are looking for the image of the Head of the country in the candidate.”

The expert has closed the interview by ethical problems of the implementation of the concept of political brand in the electoral context and considered that the law has to help with determining the ethical limits in its implementation.

This interview helped the researchers to understand the main political and legal specificities of the 2019’s presidential elections and the main problems of its context. This observatory study helped in the construction of the interview’s guide for the second part of the study.

To open the interview, the experts described the social evolution of Tunisia before and after the revolution of 2019 and its impact on the voter’s behavior. In addition, he talked about the importance of the entrance of political marketing in the scene for the candidates as well as for the voters. He resumes this by saying,“Tunisia is a country in transition between several states; we go from a dictatorship to a democracy, from a rather tribal, clan-based society to an open society, from a society where the choice is collective imposed by a community to a choice that becomes personal through the act of voting. In this passage enters the question of political marketing and that becomes an obligatory act for a politician. Thus, people in Tunisia, especially at the presidential level, voters base their votes on the representations that candidates provide rather than on their program”

When we asked the expert about the social specificities of the context of the elections, he mentioned that we would need to understand the specificities of the Tunisian citizen in order to understand it. He considered that “In Tunisia, we must understand that the citizen lives with a feeling of injustice and dissatisfaction from birth, that's why, during the elections he looks for a president who represents justice. In addition, the Tunisian searches for a president who presents a better version of himself to which he can project him and identify. This applies to all elections. For the 2019 elections, the people were fed up with the social class, corruption and were no longer reassured, hence, he sought to feel the return of the state, he sought justice and he had a fear that has accumulated. "What was interesting about the 2019 campaigns was the emergence of a new approach to almost P to P person-to-person candidacy and that was really innovative. People who ran on behalf of parties were plagued by this assailed image of political parties and the salient discourse was more of those who ran as individuals in a rather solitary way and spoke directly to the public and people wanted to vote on purely ethical considerations related to values and norms.” The expert also considered the voters didn’t welcome the political promises and discourse and that “There were also candidates who ran excellent campaigns in terms of marketing and communication, but who could not present a convincing speech that would allow people to project themselves.”

About the implementation of marketing and of the context of personal brand in Tunisia, the expert mentioned, “in the presidential elections, people vote in a personal and one-to-one way so the communication has to be based on the candidate himself.”

He talked also about the political discourse and its impact on the brand of the candidate y judging that it was a main problem with the candidates of 2019.

«To have a successful speech in a presidential campaign, it is absolutely necessary to have a real knowledge of the field. Then, it is necessary to present symbolic objectives in which people recognize themselves and consider important for their daily life. For example, when the candidate talks about justice and the term sounds right with the image he gives off, there is a complementarity between the image and the speech. This is where the communication of the brand to the public comes into play. The perception of the brand and the way it is displayed allows people to be reassured because people today are not assured. The non-conformity between the image and the discourse was one of the problems of the candidates in 2019.”

For the interview with the expert in geopolitics, it focused rather on the geopolitical evolution of the different elements of the context in the 2019’s presidential elections, the expectations of the public, the different campaigns, the concept of the political personal brand and its application in the Tunisian context. Moreover, he emphasized the study of the social context and the identification of public expectations for the presidential candidate.

This study served to understand the specificities of the electoral context in 2019, which helped us to elaborate the interviews’ guide for the second study

Second Study

The second study was conducted with nine candidates for the 2019 presidential elections in Tunisia who have experienced the context of building a political personal brand. Nine out of 26 agreed to respond to our guide. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in a semi-structured manner and lasted 45 minutes on average.

We have a comprehensive list, all 26 candidates who ran for president in 2019. We contacted all 26 candidates, by email, filing official applications in their offices. Only nine candidates agreed to answer our questions and welcomed us. Thus, the sample of the survey was formed by convenience. Below, in Table 2, is the information about the interviewees. Out of respect for confidentiality, the candidates are anonymous.

| Table 2 Presentation of Presidential Candidates | |||||||||

| Candidate | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

| Age | 62 | 69 | 49 | 55 | 56 | 60 | 73 | 64 | 63 |

| Type | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Number of years in politics | 10 | 49 | 10 | 16 | 36 | 10 | 50 | 39 | 5 |

| Party/ independence | Party | Coalition | Party | Party | Party | Party | Party | Coalition | Independent |

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, read and reread by the researchers during the data collection and were coded by Nvivo-12. The personal experiences of the presidential candidates provided a rich account of their different journeys.

The Nvivo software allows creating nodes, to control the content of the corpus and to mark significant extracts. The next step is the coding step to introduce the themes and sub-themes presented beforehand according to the literature, the interviews with the experts and with reference to the research topic. The following section presents findings and discussion.

Presentation and Analysis of Results

The purpose of the research is to identify the elements of the political personal brand and their role in its representation in the minds of voters, and to explore the issues involved in using personal branding strategies in a presidential campaign.

The literature has highlighted the application of the concept of personal branding in the political arena, its different elements as well as the different elements of its complex environment.

The accounts of this study revealed five main different themes around the creation and the issues facing the political personal brands in presidential campaigns.

The Environment Factors and the Context

The first theme uncovered was the main factors that candidates faced while conceptualizing their political personal brands. Many candidates highlighted the considerations they had while creating their personal brands.

The first factor presented by eight candidates was the campaign finance law and the problems, they faced to understand and respect it.

All the candidates talked about the financing irregularities in the elections and its impact on their images and on the perception of the elections in general. "One of the factors that affected the 2019 campaign was financial corruption." (G).Eight candidates considered that the financial corruption affected their personal brands management during the campaigns and they argued that "some financial irregularities committed by some candidates, which were noticed by the voters and contributed to blurring the image of all the candidates." (F). In addition, “they considered that these fraudulent practices has “(I).

The second factor that seven candidates talked about was media. They considered that it had a bigger impact than money in the creation of the images of the candidates. "In the 2019 campaign, money did not play a major role. Because there were candidates who had very large funds and means yet they had small scores, while other candidates who didn't have a lot of means were able to get very good scores." (A).

Six candidates believed that “The mass media was not neutral and influenced public opinion” (I). Actually, they considered that the media quota “was not respected” (E) and this did not give all the candidates the opportunity to present their personal brands and their qualifications properly. In addition, talking about the presidential debates, the seven candidates argued that the questions were “targeted and very limited” (I) which blurred the identities of all of the candidates.

The Political Personal Brand Identity

The second theme uncovered was the political personal brand identity. While the experiences were extremely personal, opinions were much divided. Every candidate considered his own strength points to develop his political personal brand identity.

Talking about their identities, the candidates presented four main elements: experience and history, personality, values and vision.

The first element, candidates talked about was their experience and history. Seven candidates considered that their experience was important in the creation of their personal brands and judged it the proof of their legitimacy for the position. The researchers noticed two different types of experiences presented by the candidates: the first is the experience in sovereign positions (4) and the second is the story of struggle (3).

For the first type, the candidates considered that their experience in these positions, nationally and internationally was necessary to prove their competencies “I also wanted to talk about my international experience in the political field to prove that I am fit for the job.” (E). In addition, they considered that their experience in such positions prove their personal values as presidential candidate, “I used my experience as a statesman to show my seriousness and respect for the law, integrity and public morality.” (I)

The candidates that presented their story of struggle considered that showing the image of a combatant was important after the revolution to prove their “good faith and honesty” (C). Moreover, this image served to ensure the votersthat they have the necessary skills, for example: "To show the image of a politician who has struggled a lot and has enough experience to have the necessary skills for the position of president." (E)

Talking about this, we noticed that the candidates who had a story of struggle talked about the fact that their brands were distorted before the revolution and presented a type of anti-branding that led them to implement strategies to support their real identities and brands. For example, “My image was always distorted by the previous systems, since I always fought against them. Therefore, I presented in the citizen's mind the image of a recidivist without principles without religion... so I aimed to rectify these preconceived ideas and explain my history as a fighter.” (B)

In this part, the experiences were extremely different and the candidates’ perception of the impact of their history was very different but they argued that presenting their experience to the public helped them to show their competencies. "Someone who is competent and capable of managing the three areas reserved for the president, international relations, defense and security." (D)

The second element considered by seven candidates was personality. They conceived that presenting a correct personality to the electorate helps the candidate to attract its attention and to create a good image in the voters’ minds. The candidates presented different personalities and every one of them supported it by what he wanted to communicate by it. For example:

-"I presented myself as a person, who is frank, honest, sincere, selfless but determined. I wanted to communicate a certain willingness of someone who was ready for justice who was not included in the system and who has the courage to make critical decisions." (A)

- "To present someone who carries a vision and is able to act courageously to protect the country and defend it." (B)

- "I presented myself as a director who can be a leader, savior of the country, who can have a closeness to the citizens by the rigorous application of the law." (D)

Having an impactful personality was one of the points that the majority of the candidates argued about its importance in an electoral context.

The third element related to the political personal brand identity presented by the candidates was personal values. All the candidates affirmed that personal values are very important for the local audience. The nine candidates considered that being honest and expressing their true beliefs is necessary “I wanted to be true to my beliefs, to the education I received, to what I think is right.” (F)

Four of them considered that the values they always fought for were the core of democracy and based their campaigns on“Democracy is not only based on freedom but it also has a social aspect which is social justice." (H)

Nevertheless, three others considered that their personal values affected negatively their campaigns. For example “When I was asked about this, I answered frankly: "Yes, I am for equality in inheritance”and the public reaction was generally negative, and this influenced the voting result” (D).

The fourth element introduced by the nine candidates was their vision. All the candidates argued about the importance of having a clear vision during a presidential campaign. The visions they presented were, for them, representative of their whole programs and strategies presented in their campaigns.

- "Tunisia is an organized state, a state of law, discipline, justice, culture, science." (I)

- “Order and freedom are not enemies when one is in a state of law. The rule of law is a state that respects its citizens." (F)

- "Our vision was to build a strong rule of law besides the slogan of the campaign was a strong and just state." (D)

They judged that having a clear vision makes them “more understandable by the audience” (F) and this helps them to present their brands properly.

Creating a clear identity was very important for the candidates. We noticed that they worked on different elements and had different considerations while creating and implementing their personal brands identities.

Positioning Strategy

The third theme uncovered was the importance of the positioning strategy in an electoral campaign. Five candidates mentioned that they needed to have recourse to different analysis in order to understand the audience and its needs. These analyses helped them to elaborate a discourse that meets the electoral expectations. For example:

- “The candidate analyzes the semantics of the society to which he/she is applying to represent, its needs and demands in order to reconstruct his/her speech so that it is recognizable and understood by his/her audience." (E)

- "It was also necessary to study geostrategic and social factors in order to prepare a convincing speech." (G).

- "The candidate must analyze the history of his people, their problems and demands so that he can detect their problems." (H)

Talking about the positioning strategies, the candidates mentioned that they had to consider the political environment after the revolution in their positioning strategies. Four candidates considered that the scene was divided into “pro the 2011’s engagement and against it” (B)

The candidates had also explained that they had to differentiate from the others on the scene. All the candidates presented several differentiation strategies and mentioned, “Being in an electoral competition with 25 other candidates made the differentiation a must” (E). For this, we noticed that the candidates had clear differentiation strategies, for example:

- "My differentiation from the other candidates is my history of fighting for freedom for democracy, for social justice for equality..." (B)

- "I have positioned myself "against corruption" and am even waging a war against corruption in the country." (D)

- "My positioning was based on technical skills. I saw that I was following the qualifications of the president's position" (E)

- "The positioning we proposed was a total break with the old system in terms of governance. A progressive choice from the conservatives." (C)

- "The main thing that differentiated us from the others was that we were not set in the short term." (F)

As mentioned, the differentiation strategies were very important in such a competitive environment. In addition, the differentiation itself was based on different aspects, mainly on, competencies, history of struggle and programs

Political Personal Brand Image

The fourth theme uncovered by four candidates was their personal brands images. They affirmed that the environment factors especially mass media influenced a lot the voters’ perceptions. They talked about the impact of the lack of communication on their images and considered that the audience was “conditioned by the mass media” (A) which made it incapable to judge them objectively.

Therefore, the candidates mentioned that some of what they wanted to communicate has had a result. For example, the candidates who talked about blurring their images before the revolution mentioned that some of the targeted public has perceived them differently after their campaigns. "Young people perceived my relationship with my wife as a sign of open-mindedness and a love story that he would like to live." (B)

Some others considered that their speeches were the key of their brands and mentioned that people started having a good perception of them after communicating some of their values and program points. "People started to be interested in what I was saying especially since they noticed that I was offering a different discourse about the economic aspects." (A)

All the candidates considered that their images were not perfectly perceived because of the media problems.

Permanent Campaigning

The fifth theme uncovered was permanent campaigning. Thus, five candidates affirmed the role of having a permanent campaign and of communicating their brands before the electoral competition. They considered it important to create a clear image in the voters’ minds before the competition in order to be able to concentrate in communicating their program during the campaign (D).

Some of the candidates talked about their permanent campaigns before the elections, for example:

- ...I did a permanent communication during the five years that preceded the election campaign. During this period, one of the means that I considered effective was the regional radios where I made several interventions..." (D)

The participants considered that the perfect way to communicate permanently is to be present in the political scene in order to present positions and solutions. "The permanent campaign of a candidate must be aimed at his presence in the political arena to present positions and solutions to the different problems that he detects through tours in the country." (G).

Discussion and Managerial Implications

Overall, compared to the wide research on the concept of political personal brands, its conceptualization and management in such a competitive context has not been thoroughly explored. This paper seeks to contribute to the political personal branding literature as a theoretical lens to understand the creation, implementation and management process of personal political brands in different contexts.

Theoretical Implications

The literature has highlighted the application of the concept of personal branding in the political arena, its different elements as well as the different elements of its complex environment.

Several candidates interviewed addressed the concept of brand identity, which is consistent with the previous researches (Pich et al., 2020, Pich and Armannsdottir, 2022). They used the different elements of identity to create their brands and reinforce their images.

This study revealed that the different candidates with different background mentioned the same elements to create their identities in different ways; the political candidates confirmed that they wanted to communicate their technical skills and considered it a factor in the legitimacy of their candidacies. This finding is affirmed by the literature as several researchers have considered it one of the keys to a successful personal brand (Roberts, 2005; Shepherd, 2005; Mills et al., 2015; Johnson, 2017).

The candidates linked their skills to their personal experiences and stories. Indeed, they considered that by communicating their political and social backgrounds, they present material evidence to the electorate of their merits of the position. Thus, each of the candidates relied on the specificities of their experience to create their identity and their communication strategy. The literature highlights the importance of history and experience in building a unique and identifiable political personal brand (Norris, 2000; Palmer, 2004; Shepherd, 2005; Parmentier et al., 2013; Manai and Holmund, 2015; Hansen and Treul, 2021; Gailmard, 2022). Indeed Parmentier et al. (2013) considered that the politician's personal experience is one of the most powerful points of differentiation in his or her branding. They even consider that the personal brand develops its positioning and gains maturity based on its experience and history.

In addition, this study revealed that the candidates attached importance to the impact of personality traits on the perception of the electoral public. Indeed, they considered that the image of the politician in the minds of the candidates depends primarily on his personality traits as a citizen. In this respect, research on personal brand personality confirms their statements (Singer, 2002; Westen, 2007; Pich and Dean, 2015; Grimmer and Grube, 2019; Jain et al., 2018; Nai et al., 2022). Parmentier et al. (2013) confirmed the importance of personal brand personality to differentiate from competitors and to strengthen its identification with the voting public. Takácsand et al. (2018) considered that personality is the foundation of the personal brand.

The candidates had also mentioned their differentiation strategies in the electoral campaigns and explained that the competitive environment made it essential to be noticeable by the audience.In the literature, the strategy of differentiation from others is considered essential for a political personal brand given the complexity of its environment (Parmentier and Fischer, 2012). Thus, the points of differentiation are related, according to researchers (Baines et al., 2012; Parmentier and al., 2013; Ordabayeva and Fernandes, 2018), to the social capital, personality, and personal experience of the politician. In this sense, the competitive differentiation is considered as the primary focus of political personal brands (Nielsen, 2015; Rutter et al., 2018; Pich et al., 2019; Fossen et al., 2019).

Talking about their images, the majority of respondents admit its importance. They believe that different groups in society perceive them differently. According to them, this is due to several factors: the political family of the citizens' group, anti-branding and ineffective or insufficient communication strategy.

The researchers confirm the importance of the management of the political personal image and its importance in the electoral context. They consider the political personal brand image to be the key to the trust between the candidate and the public which promotes its success (Baines and O’Shaughnessy, 2014; Nielsen, 2016; Armannsdottir et al., 2019). The perceptions formed in the minds of voters are directly related to candidates' self-presentation, nonverbal traits, verbal statements, actions, and performances (Labrecque et al., 2011; Roberts, 2005).

Managerial Implications

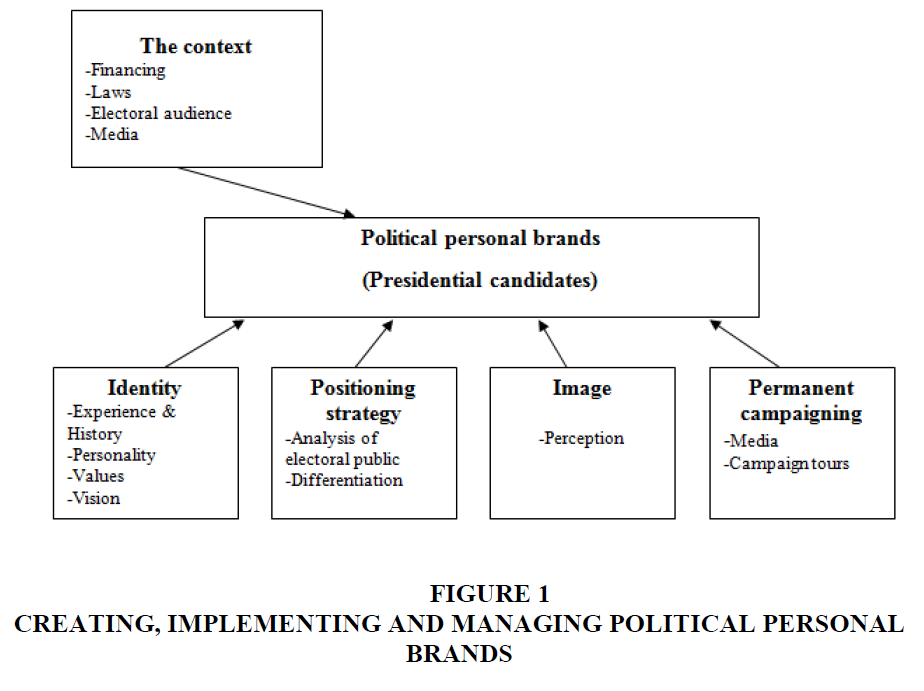

The theoretical background proves that a personal brand does not come naturally and it takes many elements to emerge. From the findings of this study, a systematic framework is introduced in Figure 1 that may provide guidance to managing a political personal brand. The political personal brand issues tool can be used in different ways. First, it can help politicians to have a complete vision of the different elements of the context that they have to consider while creating their personal brands during a presidential election. Second, the tool can be used to create new political personal brands and adjust existing in order to have solid campaigns. Third, the tool can help politicians to map out their personal brands’ strategies in order to adjust it routinely during campaigns.

This systematic framework aims to help politicians to develop their personal brands. While using this framework, politicians need to adjust routinely the contextual elements and their different strategies in order to have good results (Nwarisi et al., 2021; Grabe and Bas, 2022). The five main themes discussed in this paper have been illustrated in Figure 1. The relation between the different elements has been co-formulated with the experts and the interviewers.

In order to explain more this framework the table-3 below will serve to explain its different parts and its different usages.

| Table 3 Key Themes Related to Political Personal Brands | |

| Key principle issues | Personal brand issues framework |

| The context | Includes the different contextual elements in an electoral campaign that may influence the creation and the management of a political personal brand that the politician has to analyze. |

| Political personal brand identity creation | Based on the different elements of the personal brand identity and the elements of the context, politicians are meant to develop coherent identity including tangible and intangible elements. |

| Positioning strategy | Analyzing the audience and the political scent in order to create a good positioning strategy coherent with the identity of the personal brand and noticeable by the audience. In a competitive context, politicians are meant to consider differentiation elements in their positioning strategies |

| Political personal brand image | The personal brand image is created by a good communication strategy. The main purpose is to have an image that matches the identity previously created. For this the candidates has to create a strong communication strategy that matches their identities and the audience expectations |

| Permanent campaigning | Permanent campaigning was judged by the participants in the research as the most useful way to create a clearer perception in the mind of the audience. The candidate need to adjust his identity routinely during his permanent campaign in order to make it effective |

Conclusion

The theoretical framework considers that personal branding is not natural and is the result of many elements. The results of this study show the importance of political personal branding in an electoral context, the issues at stake, and the elements that impact political personal branding. This research resulted in a model, which will serve as a reference for creating, consolidating, positioning or repositioning a political personal brand during an election campaign. This model highlights all the elements that politicians, political advisors and communications agencies must consider to ensure electoral success. This research has contributed to the literature on understanding political personal brands, particularly those associated with presidential candidates. In the literature, studies have focused on a few key elements of the political personal brand. This study, therefore, contributes by bringing several elements together in one research study and exploring the process of creating and managing the political personal brand in a challenging environment.

This research makes a scientific contribution by presenting some limitations previously discussed and reveals the beginnings of future research avenues. First, the sampling, out of the 26 candidates, we only have nine candidates who were able to respond to our guide. It will be interesting to expand our sample and target all politicians. Then the method used, it will be interesting to use a quantitative method to be able to generalize the results. Second, the proposed model is only a synthesis of theoretical and empirical results, the list of elements is not exhaustive, and other studies can complete the list. Third, it is interesting to conduct a survey among voters and to see their perceptions of the candidates interviewed and then to compare the desired identity with the perceived identity.

References

Agnoletti, M.F. (2017). La perception des personnes: psychologie des premières rencontres, édition Dunod.

Antoniades, N. (2020). Political Marketing Communications in Today’s Era: Putting People at the Center. Society, 57(6), 646-656.

Armannsdottir, G., Pich, C. & Spry, L.(2019). Exploring the creation and development of political co-brand identity: A multi-case study approach. Qualitative market research: An international journal, 22(5), 716-744.

Armannsdottir,G.,Carnell,S.,& Pich, C. (2019). Exploring Personal Political Brands of Iceland’s Parliamentarians. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1-2), 74-106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baines, P.R. & O'Shaughnessy, N.J. (2014). Political marketing and propaganda: Uses, abuses, misuses. Journal of Political Marketing, 13(1-2), 1-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baines, P.R., Worcester, R. M., Jarrett, D. & Mortimore, R. (2012). Market segmentation and product differentiation in political campaigns: A technical feature perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 19(1-2), 225-249.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Billard, T.J. (2018). Citizen typography and political brands in the 2016 US presidential election campaign. Marketing Theory, 18(3), 421-431.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bosch , J., Venter , E., Han , Y. & Boshoff, C. (2006). The impact of brand identity on the perceived brand image of a merged higher education institution: Part one. Management Dynamics: Journal of the Southern African Institute for Management Scientists, 15(2), 10-30.

Braun , V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bruno, S. & Rodrigues, S.(2019). The role of personal brand on consumer behaviour in tourism contexts: the case of Madeira. Enlightening Tourism. A Pathmaking Journal, 9(1), 38-62.

Chen , C.P.(2013). Exploring personal branding on YouTube. Journal of internet commerce, 12(4), 332-347.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Clarke, V. & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Successful qualitative research, 1-400.

Confente, I. & Kucharska, W. (2021). Company versus consumer performance: does brand community identification foster brand loyalty and the consumer's personal brand?. Journal of Brand Management, Volume 28, 8-31.

Costa , A. C. p. D. R. & Hallman , K. (2022). Determinants of personal brand construction of national football players on Instagram. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 22(3-4), 189-210.

Creely, E. & Henriksen, D. (2019). Creativity and digital technologies. Encyclopedia of Educational Innovation, 1-6.

Cwalina, W., Falkowski, A. & Newman, B.I. (2011). Political marketing: Theoretical and strategic foundations, 1er edition, Routledge, 352.

Evrard, Y., Pras, B. & Roux, E. (1993). Market-Etudes et recherches en marketing: fondements, méthodes, 1er edition, Nathan, 629.

Falkowski, A. & Jab?o?ska, M. (2020). Moderators and mediators of framing effects in political marketing: Implications for political brand management. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1-2), 34-53.

Fossen, B. L., Schweidel, D. A. & Lewis, M. (2019). Examining Brand Strength of Political Candidates: a Performance Premium Approach. Customer Needs and Solutions, 6, 63-75.

Gandini, A. (2016). Digital work: Self-branding and social capital in the freelance knowledge economy. Marketing theory, 16(1), 123-141.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gehl, R. W. (2011). Ladders, Samuraiand Blue Collars: Personal Brand in Web 2.0,. First Monday, 16(9), 3-24.

Grabe, M. E. & Bas, O. (2022). The genderization of american political parties in presidential election coverage on network television (1992–2020). International Journal of Communication, 16, 23-36.

Green , R. T. (2016). Constructivism and comparative politics. 1er edition, Routledge. 61.

Grzesiak, M. (2018). Personal brand creation in the digital age, 1er edition, Palgrave Pivot, 185.

Hansen, E. R. & Treul, S. A. (2021). Inexperienced or anti-establishment? Voter preferences for outsider congressional candidates. Research & Politics, 8(3), 205-216.

Harris, P. & Lock, A. (2010). “Mind the gap”: the rise of political marketing and a perspective on its future agenda. European journal of marketing, 44(3/4), 297-307.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jain, V., Chawla, M., Ganesh, B. E. & Pich, C. (2018). Exploring and consolidating the brand personality elements of the political leader. Spanish Journal of Marketing, 22(3), 295-318.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Johnson, K.M. (2017). The Importance of Personal Branding in Social Media: Educating Students to. International journal of education and social science, 4(1), 21-27.

Korzh, A. & Estima, A. (2022). The power of storytelling as a marketing tool in personal branding. International Journal of Business Innovation, 1(2), e28957- e28957.

Labrecque, L. I., Markos, E. & Milne, G. R. (2011). Online personal branding: processes, challenges, and implications. Journal of interactive marketing, 25(1), 37–50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, M.R. & Chen, T. (2015). Digital creativity: Research themes and framework. Computers in human behavior, 42, 12-19.

Manai, A. & Holmund, M. (2015). Self-marketing brand skills for business students. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(5), 749-762.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Marland , A. & DeCillia, B. (2020). Reputation and Brand Management by Political Parties: Party Vetting of Election Candidates in Canada. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 32(4), 342-363.

Marland, A. & Wagner, A. (2020). Scripted messengers: How party discipline and branding turn election candidates and legislators into brand ambassadors. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1-2), 54-73.

McNally, D. & Speak, K. D. (2002). Be your own brand: A breakthrough formula for standing out from the crowd. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 28p.

Mills, S., Patterson, A. & Quinn, . L. (2015). Fabricating celebrity brands via scandalous narrative: crafting, capering and commodifying the comedian, Russell Brand. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(5-6), 599-615.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nai, A. & Maier, J. (2020). Dark necessities? Candidates’ aversive personality traits and negative campaigning in the 2018. American Midterms, electoral studies, 68, 102-233.

Nai, A. & Maier, J. (2020). Is negative campaigning a matter of taste? political attacks, incivility, and the moderating role of individual differences. American Politics Research, 49(3), 269-281.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nai, A. & Martinez i coma, F. (2019). The personality of populists: provocateurs, charismatic leaders, or drunken dinner guests?. West European Politics, 42(7), 1337-1367.

Nai, A., Martinez i Coma, F. & Maier, J. (2019). Donald Trump, Populism, and the Age of Extremes: Comparing the Personality Traits and Campaigning Styles of Trump and Other Leaders Worldwide. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 49(3), 609-643.

Nai, A., Tresch, A. & Maier, J. (2022). Hardwired to attack. Candidates’ personality traits and negative campaigning in three European countries. Acta Politica, 57(4), 772-797.

Needham, C & Smith, G. (2015). Introduction: Political Branding. Journal of Political Marketing, 14(1-2), 1-6.

Niculae, V., Suen, C., Zhang, J., Mizili, N. & Leskovec, J. (2015). Quotus: The structure of political media coverage as revealed by quoting patterns. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web, 798-808.

Nielsen, S. W. (2015). On Political Brands: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Political Marketing, 16(2), 118-146.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nielsen, S. W. (2016). Measuring political brands: An art and a science of mapping the mind. Journal of Political Marketing, 15(1), 70-95.

Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in postindustrial societies, 1er edition, Cambridge University Press. 1-22.

Nwarisi, S. N., Igwe, P. & Kalu, S. E. (2021). Political rebranding and electorate acceptance of political parties in Nigeria. GPH-International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research, 4(7), 64-85.

Ordabayeva, N. & Fernandes, D. (2018). Better or different? How political ideology shapes preferences for differentiation in the social hierarchy. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 227-250.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Palmer, J. (2004). Source strategies and media audiences: Some theoretical implications. Journal of Political Marketing, 3(4), 57-77.

Parmentier, M.A. & Fischer, E. (2012). How athletes build their brands. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 11(1-2), 106-124.

Parmentier, M.A., Fischer, E. & Reuber, A. R. (2013). Positioning person brands in established organizational fields. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 41, 373-387.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pellemans, P. (1999). Recherche qualitative en marketing: perspective psychoscopique. 1er edition, De Boeck Supérieur, 400.

Peters, T. (1997). The brand called you. Fast company, 10(10), 83-90.

Pich, C. & Armannsdottir, G. (2022). Political Brand Identity and Image: Manifestations, Challenges and Tensions. Political Branding in Turbulent times, 9-32.

Pich, C. & Dean, D. (2015). Political branding: sense of identity or identity crisis? An investigation of the transfer potential of the brand identity prism to the UK Conservative Party. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(11-12), 1353-1378.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pich, C. & Newman, B.I. (2019). Evolution of political branding: Typologies, Diverse Settings and Future Research. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1-2), 3-14.

Pich, C. (2022). Political branding: a research agenda for political marketing. A Research Agenda for political Marketing, 121-142.

Plescia, C., Kritzinger, S. & Spoon, J.J. (2021). Who's to blame? How performance evaluation and partisanship influence responsibility attribution in grand coalition governments. European Journal of Political Research, 61(3), 660-677.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roberts, L.M. (2005). Changing faces: Professional image construction in diverse organizational settings. Acad. Manage. Rev., 30(4), 685–711.

Rutter, R. N., Hanretty, C. & Lettice, F. (2018). Political brands: Can parties be distinguished by their online brand personality?. Journal of Political Marketing, 17(3), 193-212.

Scammell, M. (2015). Politics and image: The conceptual value of branding. Journal of political marketing, 14(1-2), 7-18.

Shafiee, M., Gheidi, S. & Khorrami, M. S. (2020). Proposing a new framework for personal brand positioning. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 26(1),45-54.

Shepherd, I.D. (2005). From cattle and coke to Charlie: Meeting the challenge of self marketing and personal branding. Journal of Marketing Management, 21(5-6), 589-606.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Simons, G. (2016). Stability and change in Putin's political image during the 2000 and 2012 presidential elections: Putin 1.0 and Putin 2.0?. Journal of Political Marketing, 15(2-3), 149-170.

Simons, G. (2019). Putin’s international political image. Journal of Political Marketing, 18(4), 307-329.

Singer, C. (2002). Political Branding In both political campaiging and consumer marketing, branding is more art than science. Brandweek-New York, 43(34), 19-19.

Smith, G. & French, A. (2009). The political brand: A consumer perspective. Marketing theory, 9(2), 209-226.

Speed, R., Butler, P. & Collins, N. (2015). Human branding in political marketing: Applying contemporary branding thought to political parties and their leaders.. Journal of Political Marketing, 14(1-2), 129-151.

Susila, I., Dean, D., Yusof, R., Setyawan, A, & Wajdi, F. (2019). Symbolic political communication, and trust: a young voters’ perspective of the Indonesian presidential election. Journal of Political Marketing, 19(1-2), 153-175.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Takács, I., Takács, V. & Kondor, A (2018). Empirical Investigation of Chief Executive Officers' Personal Brand. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 26(2), 112-120.

Tarnovskaya, V. (2017). Reinventing Personal Branding Building a Personal Brand through Content on YouTube. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 3(1), 29-35.

Te'eni-Harari, T. & Bareket-Bojmel, L. (2021). An integrative career self-management framework the personal-brand ownership model. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 73(4), 372-382.

Thompson-Whiteside, H., Turnbull, S. & Howe-Walsh, L. (2018). Developing an authentic personal brand using impression management behaviours: Exploring female entrepreneurs’ experiences. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 21(2), 166-181.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van Der Pas, D.J. & Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender differences in political media coverage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114-143.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Westen, D. (2007). Branding the Democrats. The American Prospect, 18(5), 44.

Received: 16-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14188; Editor assigned: 17-Oct-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-14188(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Jan-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-14188; Revised: 29-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14188(R); Published: 18-Mar-2024