Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

The Importance of Feedback Seeking Behavior To Increase Employees Performance In Higher Education Institutions

Dorojatun Unes

Abstract

This study examine influence of feedback seeking behavior (FSB); competence; motivation; trust on work performance employees and lecturers here are referred as 'employees' in State Universities in Central Java. The population in this research is the employees (employees and lecturers) of state universities in Central Java; they are employees of Semarang State University, Jenderal Soedirman University and Diponegoro State University. The approximate number in those universities is around 3,000-4,000 people. This study applies SEM-PLS analysis. The results reveal that feedback seeking behaviour has negative effect on competence; on the other hand, the feedback-seeking behaviour has a positive and direct effect on work performance; while competence has positive and significant effect on motivation; furthermore, motivation has positive and significant relationship on work performance; and trust is not a significant determinant moderating seeking feedback on the relationship between behaviour and work performance. This study provides pertinent results and description of how this shifting of informal self-learning from the Indonesian perspective, specifically in state universities in Central Java, Indonesia. This is one of few studies to examine the FSB, Competence, motivation trust and on performance.

Keywords

Feedback-Seeking Behaviour, Work Performance, Competence, Motivation, Trust.

Introduction

In general, employees conduct study in their workplace informally, in that process they also learn based on their interactions with people who are involved with their work (Tannenbaum et al., 2010). There is pertinent relevance of informal social interaction in workplace (Westerberg & Hauer, 2009; Eraut, 2007). Given social nature of learning in workplace, ways in which employees actively form and use interpersonal relations become a growing focus in organisation learning area (Grant & Ashford, 2008; Hakkarainen et al., 2004; Westerberg & Hauer, 2009). One of main components method of informal learning in the workplace is feedback (Tannenbaum et al., 2010).

Recent studies on feedback area revealed that employees are not passively awaiting feedback during performance reviews; instead, they were proactively seeking feedback during daily interactions in their workplace (Ashford et al., 2003). High degree of FSB or level of seeking feedback behavior within organisation appears to have an impact on some of employees who are actively aiming to improve their performance (Barner-Rasmussen, 2003). Nevertheless, most research on seeking responses has focused on lower level employees, and relatively slight is recognised about dynamics of “feedback seeking” for employees across different hierarchical levels (Ashford et al., 2003). Study shows that many employees have difficulties in obtaining valuable feedback information, as they felt they are in a state called “feedback vacuum” (Ashford et al., 2003). This study examined influence of determinants, which are: feedback seeking behavior (FSB); competence; motivation; trust and work performance employees and lecturers here are referred as “employees” in State Universities in Central Java.

Literature Review

Feedback Seeking Behavior (FSB) and Performance

Ashford & Cummings (1983) emphasise that valuable feedback to employee's performance is relevant, because it contains supportive information on how well they perform, how their superiors evaluate them, and what is needed to be modified to accomplish goals and objectives (Ashford et al., 2003 ). Theoretical reasoning for the relationship between FSB and job performance could be explained in two ways. First, feedback decreases doubt that employees may experience, and help them to explain their other roles expect from them. Cheramie (2013) in his study also found that employees who proactively seek feedback from their supervisors have a higher level of career success through obtaining relevant information to expand their performance. According to goal setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990), when employee received feedback indicating that they have not achieved their goals at required level, they become motivated to put greater effort towards their goal. From a goal-setting perspective, Ilies & Judges (2005) argue that feedback will be positively related with higher performance since feedback allows employees to appraise their current level of performance relating to desired work objectives.

Strengthen the Trust Effect on the Supervisor

Feedback will have impact on work performance; this kind of state exists if employees trust their superiors. This belief is defined as “a psychological state comprising intention to accept expectations or behaviour of others” (Rousseau, 1998). Ability could be described as skills and knowledge needed to improve one's performance; while virtue describes extent to which employees has goodwill to their supervisor which is based on loyalty, sincerity, and supportive relationships (Mayer et al., 1995). Given that, FSB operates in mutual relationships between employees and supervisors, and employees' trust in supervisors could be linked to their FSB. If employees think their superiors are capable and willing to provide beneficial feedback on performance, employees will actively seek feedback from their superiors (Choi et al., 2014). Stone & Stone (1985) found that when participants in his experiment received feedback from experienced reviewers with good rating skills, they reported more accuracy in feedback they received. In addition, similar concepts to beliefs, such as source credibility (Renn & Fedor, 2001; Steelman et al., 2004), have been well-researched as FSB predictors. Thus, it can be expected that when employees consider their supervisors as feasible beliefs, they will receive the feedback and use them to improve their performance.

Influence of FSB, Competence, Motivation to Performance

Drake et al. (2007) suggests that there are 3 levels of performance feedback which are: wages only, wages coupled with non-financial feedback and wages coupled with non-financial and financial feedback. Motivating employees in a company is important in improving company performance (Drake et al., 2007). In an institution, employees have a perception that their duties and roles as a competence degree in which the employees can do their job properly (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 and Drake et al., 2007). The effect of these perceptions will generate a belief that employees can accomplish their work performance. Furthermore, it can be said that employees with a certain level of confidence would be able to assert their job quite well, and if they have that level of competence, their competence will have a direct impact on employee motivation (Elliot et al., 2000). The employees’ behaviour to get performance feedback affects employee competence, this competence is individual assumptions about how well they can accomplish specified-assigned task. Spreitzer (1995) emphasised that employees who are motivated will be able to improve their work performance. Moreover, motivated employees are important and this motivated state needs to be maintained by organization (Spreitzer, 1995).

The Hypotheses of the Research

The Research hypotheses tested are as follows:

H1 The greater the level of feedback seeking behaviour the greater the level of competence.

H2 The greater the level of feedback seeking behaviour the greater the level of work performance.

H3 The greater the level of competence the greater the level of motivation.

H4 The greater the level of motivation the greater the level of work performance

H5 Trust moderate the relationship between feedback seeking behaviour and work performance

Methodology

The population in this research is the employees (employees and lecturers) of state universities in Central Java; they are employees of Semarang State University, Jenderal Soedirman University and Diponegoro State University. The approximate number in those universities is around 3,000-4,000 persons. This study applies SEM-PLS analysis. The sample in this study is between 100-200 samples, by using normality assumption and applies Maximum Likelihood Estimation techniques (Sholihin & Ratmono, 2013). The data collection in this study applies structured and closed questionnaire (Brace, 2018). The questionnaire will contain a series of statements or questions carefully arranged to stimulate a reliable response (Collis & Hussey, 2003). The statement in the questionnaire will be measured using Likert scale of 1-5 (Brace, 2018). The data analysis in this study will be divided into two parts, namely descriptive and inferential analysis. Descriptive analysis will provide statistical description of respondents' descriptions, such as age, employment, and sex of respondents. While, the inferential analysis will provide an analysis of causal relationship between determinants (Sholihin & Ratmono, 2013) using analysis SEM_PLS with warp PLS 3.0.

Results and Discussion

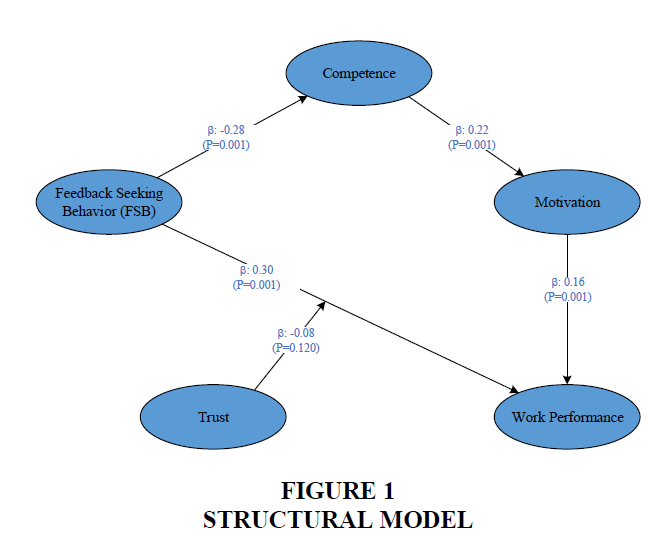

Based on the results describe in Figure 1. Above, average path coefficient (APC) has an index of 0.207 with a p-value of 0.001. While, an average R-squared (ARS) has an index of 0.095 with p-value<0.034. APC and ARS have values below 0.05. Furthermore, average variance inflation factor (AVIF) index value of the model is 1.157; it is below cut-off value of 5(<5); Thus, the model is fit. The correlation between the constructs measured by the path coefficients and the level of significance. The significance level used in this study is 5%. The table below illustrates the results of research on the effect size that has been obtained based on the data:

Table 1 presents the results estimated path coefficients and the p-value. Based on Table 1 it can be concluded that there is a negative relationship between feedbacks seeking behavior (FSB) on competence; the path coefficient is -0.282 and significant, so it can be concluded H1 is rejected. The results show the effect size estimate the influence of the FSB on competence is 0.080. Effect size can be grouped into three categories: low (0.02), medium (0.15), and large (0.35) (in Sholihin & Ratmono, 2013). Effect size FSB influence to competence is considered as vulnerable, which means the FSB variable influencing variables competence at 8% and 92% is influenced by other variables.

| Table 1 Path Coefficients and the p-values | |||||

| Criteria | Variables | FSB | CMP | MOT | TRUST * F |

| Path coefficients | CMP | -0.282 | |||

| MOT | 0.222 | ||||

| WORKPERF | 0.295 | 0.162 | -0.075 | ||

| p-values | CMP | <0.001 | |||

| MOT | <0.001 | ||||

| WORKPERF | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.121 | ||

| Effect sizes for path | CMP | 0.080 | |||

| MOT | 0.049 | ||||

| WORKPERF | 0.107 | 0.039 | 0.012 | ||

FSB has a positive effect on work performance; this result can be concluded through the path coefficient value of 0.295; with significance level of 0.001, which is <0.05, so that H2 is accepted. This figure indicates that if there is an increase in FSB, and work performance increase by 0.295 and vice versa, any decrease of FSB, work performance will decrease equal to 0,295. The results show the effect size estimation FSB influence on performance is 0.107 which was included in a weak group. This means that the FSB variable affects PTN employee performance variable of 10.7% and the rest of 89.3% is influenced by other variables.

Competence has positive effect on motivation. This can be concluded through path coefficient value of 0.222 with a significance level of 0.001; which is <0.05, so it can be concluded that H3 is accepted. This figure indicates that if there is an increase in the employees’ competence, the motivation will increase by 0.222 and vice versa. The result shows the effect size estimation value of 0,049 is considered weak. It means that competence only affects employees’ motivation by 4.9% and 95.1% is influenced by other variables.

Motivation positively influence work performance. This is based on the path coefficient value of 0.162 with a significance level of 0.006; which is <0.05, so it can be concluded that H4 is accepted. This figure indicates that if there is an increase in employees’ motivation, then work performance will increase by 0.162. The results show the effect size estimation motivational influence on performance is 0.039, it is also considered as weak influence. It means that the motivation influences the employees’ work performance by only 3.9% and the rest influence, which is 96.1%, is done by other variable.

The result shows that trust has negative affect on the relationship between FSB and work performance. It can be observed by path coefficient value of -0.075 with a significance level of 0.121> 0.05, so it can be concluded that H5 is rejected.

Discussion

The results of the empirical test of this study indicate that there is a negative relationship between FSB on competence. These results contrast with several previous studies conducted by: Mayer et al. 2005, the research suggested that the FSB is expected to facilitate achievement of employee’s objectives by helping the employees to monitor their work progress and find solutions to problems related to their specified work objectives. The results of this study also contradict the goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990) which emphasised that when employees receive feedback which indicate they have not achieved their goals at certain level, they become motivated to put bigger effort toward their goals or objectives; the results of this research might be affected by the fact that employees have implemented specific level of target, so they might think that they do not need to receive any feedback from their superiors.

The result of the second hypothesis shows that FSB has a positive effect on work performance. This result supports the perspective idea of establishing goals that was emphasised by Ilies & Judge (2005), which also explain that feedback would be positively associated with higher performance; due to the capability of feedback in allowing employees to evaluate their current level of performance related to desired work objectives. These results also support previous research by Renn & Fedor (2001) who argued that FSB has a positive influence on quality and quantity of their employee’s objective achievement set by valuable input, based on their role and performance.

This empirical test result supports previous research by Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 in Drake et al., 2007, whereas in an organization or institution. The results of this research also support research conducted by Elliot et al. (2000) who stated that employees with a certain level of confidence will be able to claim that they can do the job well, and if they have that level of competence, their competence will have a direct impact on employee motivation.

The fourth hypothesis test result of this study suggests that motivation has positive influence on work performance. This result supports a study conducted by Drake et al. (2007) who emphasised that motivation influences employee’s work performance. Specifically, on their intention or willingness to work at better performance level.

A fifth empirical test result in this study indicates that trust has negative effect on the relationship between the FSB and work performance. This result is contrast with previous studies conducted by Vancouver & Morrison (1995). They argue that FSB took a pertinent role in amplifying the mutual relationships between employees and supervisors or superiors, so that employee confidence in supervisors or superiors can be closely linked to their intensity to seek feedback that will result in a premise “if employees think their superiors are capable and willing to provide feedback useful on performance, employees will actively seek feedback from their superiors”. This result is possible if employees did not have any confidence on their superiors.

Conclusion

There is a negative relationship between FSB on competence; FSB has positive influence on employees; work performance; competence has positive effect on employees’ motivation; motivation has positive influence on employees’ work performance; and trust has a negative effect on the relationship between FSB and work performance. Respondents from this research are lecturers and employees at three state universities in Central Java, so it might be reflected accurate results. We suggest that future research will provide the data collection on the other state universities in Indonesia or perhaps private universities also. This study also has limitations in translating the relationship between variables in certain stages. The application of some determinants might not be able to capture of how behavioural assessment analysis is applied to analyse the relationship between these determinants in the institutions such as universities, further research are advised to revise the relationship between determinants. It is advisable for further researchers to use samples or respondents from private companies or other institutions.

References

- Ashford, S.J., Blatt, R., & Walle, D.V. (2003). Reflections on the looking glass: A review of research on feedback-seeking behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 29(6), 773-799.

- Ashford, S.J., & Cummings, L.L. (1983). Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32(3), 370-398.

- Barner-Rasmussen, W. (2003). Determinants of the feedback-seeking behaviour of subsidiary top managers in multinational corporations. International Business Review, 12(1), 41-60.

- Brace, I. (2018). Questionnaire design: How to plan, structure and write survey material for effective market research. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2013). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Elliot, A.J., Faler, J., McGregor, H.A., Campbell, W.K., Sedikides, C., & Harackiewicz, J.M. (2000). Competence valuation as a strategic intrinsic motivation process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(7), 780-794.

- Eraut, M. (2007), Learning from other people in the workplace, Oxford Review of Education, 33(4), 403-422.

- Grant, A.M., & Ashford, S.J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 3-34.

- Hakkarainen, K.P., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., & Lehtinen, E. (2004). Communities of Networked Expertise: Professional and Educational Perspectives.

- Vancouver, J.B., & Morrison, E.W. (1995). Feedback inquiry: The effect of source attributes and individual differences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(3), 276-285.

- Renn, R.W., & Fedor, D.B. (2001). Development and field test of a feedback seeking, self-efficacy, and goal setting model of work performance. Journal of Management, 27(5), 563-583.

- Sholihin, M., & Ratmono, D. (2013). Analysis of SEM-PLS with WarpPLS 3.0 for Nonlinear Relations in Social and Business Research. Yogyakarta: Andi Publisher.

- Spreitzer, G.M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442-1465.

- Steelman, L.A., Levy, P.E., & Snell, A.F. (2004). The feedback environment scale: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(1), 165-184.

- Tannenbaum, S.I., Beard, R.L., McNall, L.A., & Salas, E. (2010). Informal learning and development in organizations. Learning, Training, and Development in Organizations, 303-332.

- Westerberg, K., & Hauer, E. (2009). Learning climate and work group skills in care work. Journal of Workplace Learning, 21(8), 581-594.

- Cheramie, R. (2013). An examination of feedback-seeking behaviors, the feedback source and career success. Career Development International, 18(7), 712-731.

- Locke, E.A., & Latham, G.P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Ilies, R., & Judge, T.A. (2005). Goal regulation across time: the effects of feedback and affect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 453.

- Rousseau, D.M. (1998). The problem of the psychological contract considered. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 19(S1), 665-671.

- Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., & Schoorman, F.D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

- Choi, B.K., Moon, H.K., & Nae, E.Y. (2014). Cognition-and affect-based trust and feedback-seeking behavior: the roles of value, cost, and goal orientations. The Journal of Psychology, 148(5), 603-620.

- Stone, D.L., & Stone, E.F. (1985). The effects of feedback consistency and feedback favorability on self-perceived task competence and perceived feedback accuracy. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36(2), 167-185.

- Drake, A.R., Wong, J., & Salter, S.B. (2007). Empowerment, motivation, and performance: Examining the impact of feedback and incentives on nonmanagement employees. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 19(1), 71-89.

- Thomas, K.W., & Velthouse, B.A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An interpretive model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666-681.