Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

The Impact of Employer Brand on Employee Voice: The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification

Mohammad A. Ta’Amnha, School of Management and Logistics Sciences, German Jordanian University

Omar M. Bwaliez, School of Management and Logistics Sciences, German Jordanian University

Ghazi A. Samawi, School of Management and Logistics Sciences, German Jordanian University

Keywords

Employer Brand, Employee Voice, Organizational Identification, Mediating Effect, Job Demand Resource Model, Social Identify Theory, Social Exchange Theory, Humanitarian Organizations, Jordan

Abstract

A conceptual model was proposed for examining the mediating effects of organizational identification on the relationship between employer brand and employee voice. The research model was tested empirically using data collected from 276 humanitarian workers in Jordan through questionnaire. The findings supported the proposed hypotheses that organizational identification mediates the relationship between employer brand and employee voice. This paper adds significant contributions to the knowledge base and related theoretical and practical implications for the humanitarian organizations since it the first time the relationship between employer brand and voice behavior is investigated, using the job demand resource model.

Introduction

One of the key managerial issue organizations strive to promote inside their premises is encouraging their employees to share their ideas and information beyond their essential tasks and responsibilities (Detert & Burris, 2007). This is because employee voice behavior is vital for improving companies’ performance and productivity (Kim et al., 2010). Therefore, a considerable academic and professional effort is dedicated to understand employee voice and the ways it can be stimulated inside their organizations. In this study, our major focus is on the mechanism by which people exercise voice behavior. In particular, we will investigate the impact of the employer brand on employee voice behavior that has not been investigated yet, taking into consideration the mediating impact of organizational identification.

Employer brand is an institution (Ta’Amnha, 2020) that comprises of several benefits, mainly functional, economic, and social those are offered by the employing organizations (Berthon et al., 2005). This effort is conducted to promote positive job attitudes and outcomes among current employees (Kaur et al., 2020), and to improve the effectiveness of the recruitment efforts (Heilmann et al., 2013). Employer brand reflects the development of psychological contract (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004) which evidently impacts the organizational performance positively (Biswas & Suar, 2016; Tumasjan et al., 2020), that therefore it receives a considerable effort from scholars and practitioners.

Employee voice behavior is an extra-role performance exercised by employees when they find opportunities to enhance the operations and performance of their organizations, or to protect them from harmful activities (Hirschman, 1970). Literature reveals that employee voice leads to various sought after results such as enhancing the performance of organizations (Kim et al., 2010).

The organizational identification refers to the cognitive association between the definition of the organization and self-definition of employees (Dutton et al., 1994). Organizational identification improves the emotional response to one’s job and organizations (Lee et al., 2015), and affects the employee’ sense of self-worth (Dutton et al., 1994). People tend to identify themselves with their organization based on their perception and evaluation of the benefits, experience, and values they get from their organizations. Therefore, when employees receive numerous resources from their organizations, that are represented by the employer brand values in this study, they perceive their organizations positively, and therefore they tend to attach their identities with their organizations. Consequently, they are more likely to show active voice behavior, because they consider the success of their organizations as a part of their self-worth and success.

The significant of this research stems from the lack of research in respect of the factors of interest in this study. Indeed, the relationship between employer brand, as a key predictor, and employee voice behavior as a dependent factor is still empirically uninvestigated. In addition, there are few studies that investigated the antecedents and consequences of the employer brand (Charbonnier-Voirin et al., 2017). Moreover, this research response to the call of investigates voice behavior to reveals new other important antecedents that are not examined yet (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008).

This study is taking place in the humanitarian sector where workers retention is a key issue of these organizations (Korff et al., 2015; Loquercio et al., 2006; Korff, 2012). This is because they are located in risky places (Heyse, 2016), that therefore affect their workers physical and psychological health (Curling & Simmons, 2010). In addition, the uncurtaining in working environments requires ongoing contributions from workers to enhance their organizations’ responsiveness, adaptability, and operations. Accordingly, we expect that the results of this research will enhance the ability of the humanitarian organizations in understanding their employees career motives and desirable workplaces, that thus improving their attractiveness in the eyes of their workers and boosts their positive job attitudes (Benraiss-Noailles & Viot, 2021).

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the previous literature and hypotheses development. Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 presents the results and discussions. Section 5 presents the conclusion by providing the theoretical and practical implications. Finally, Section 6 presents the limitations and directions of future studies.

Literature Review

Theoretical Underpinning

To meet the objective of this study, three key theories are employed to underpin this research and explain its results, namely job demand resource (JD-R) model (Bakker et al., 2005), self-identify theory (Tajfel et al., 1979), and Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Homans, 1958; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

According to the JD-R model, each job has two key categories: Job demands and job resources. Job demands refers “to those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs.” (Bakker et al., 2005). Whereas, job resources refer to “those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that (a) are functional in achieving work goals, (b) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or (c) stimulate personal growth and development.” Bakker, et al., (2005). In this research, we believe that the employer brand values offered by organizations such as social support, training and development, and well-being support enable their employees to meet their jobs responsibilities and challenges in a very effective way and deals with the associated stress very well.

According to the self-identity theory, individuals tend to identify themselves with certain group of people when they evaluate them favorably and positively. When one’s company is perceived as the employer of choice because of the values and experiences it offers, this therefore enhances their desire to attach themselves with their organizations since they believe that their self-worth stems from their workplace attractiveness. In other words, we believe that by offering employer brand values, employees are more likely to show organizational identification job attitudes.

According to the social exchange theory, when people get support from their organizations they feel indebted to support them in return. In other words, when companies work in creating and promoting positive workplaces by offering several sorts of support and experiences, employees feel indebted to their organization so they offer their voices and ideas to enhance the performance of their organization and to protect it from any adverse consequences (Sukumaran & Lanke, 2020). In this research, we propose that the associated values of employer brand such as training and development enhance the quality and quantity of employee voice.

Hypotheses Development

Employer Brand and Employee Voice

Voice is a voluntary behavior initiated by employees when they find a chance for improvement, or to protect their organizations from harmful consequences (Hirschman, 1970). When employees share their ideas with their organizations, several benefits are attained such as solving organizational problems more effectively (Detert & Burris, 2007), improving the quality of customer services (Lam & Mayer, 2014), that thus enhancing the productivity of organizations (Kim et al., 2010). Therefore, understanding the constructive active voice behavior is one of the key topics that capture the attention of practitioners and organizations. Voice was studied from several perspectives such as psychological safety supports (Dyne et al., 2003), leadership (Detert & Burris, 2007), and perceived organizational support (Ta’Amnha et al., 2021). In this study, we will investigate the impact of a novel managerial strategy i.e., employer brand on the employee voice.

Employer brand consists of several distinctive Employment Value Propositions (EVPs) that aims at enhancing the working experiences of current employees, that also represent a promise to potential highly qualified employees (Benraiss-Noailles & Viot, 2021). Recently, Ta’Amnha (2020) conceptualized employer brand as an institution that comprise of three pillars that lead to institutionalize employer brand in organizations and provide it with the required legitimacy to compete over the organizational resources. These pillars are: Regulative (such as HR policies and producers, job descriptions and employment contracts), normative (such as training and development, succession planning, and involvement), and cultural (such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and organizational justice). From this perspective, employer brand can be integrated more effectively into the organizational practices and strategies.

We consider employer brand in this study as resources provided by organizations to their employees to enhance their ability to meet their jobs demands effectively, and to deal with the related stress and anxiety successfully. Certainly, employer brand positively improves employees wellbeing (Benraiss-Noailles & Viot, 2021), and encourages them to show positive job attitudes (Allen et al., 2003) such as voice behavior (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). Moreover, leadership which is associated with the employer brand (Ta’Amnha, 2020) was found a significant predictor of employee’s tendency to share their ideas with their organizations (Bhal & Ansari, 2007; Hu et al., 2015; Islam et al., 2019; Qi & Ming-Xia, 2014; Sari, 2019; Detert & Burris, 2007; Zhu et al., 2015; Monzani et al., 2019; Ashford et al., 1998; Frese et al., 1999).

In addition, offering training and development opportunities that is a key employer brand value (Berthon et al., 2005) enhances the self-efficacy (Bandura, 1978) and capability of employees that therefore they become more confident to exercise voice behavior. Furthermore, the working environment that is characterized by trust, cooperation, justices, and psychological safety encourage employees to share their opinions and ideas with their organizations. This particularly true when employees experience justice inside their organizations, and they believe that they are not at risk when exercising voice behavior (Detert & Burris, 2007; Ashford et al., 1998; Fodchuk and Sherman, 2008; Dyne et al., 2003). Thus, we propose that:

H1: Employer brand is positively related to employee voice.

Employer Brand and Organizational Identification

People tend to identify themselves with certain group of people such as with their employing organizations when they perceive them positively. The organizational identification refers to the cognitive connection between the definition of the organizations and self-definition (Dutton et al., 1994). Organizational identification increases the emotional response to one’s job and organizations (Lee et al., 2015), and affects the employee’ sense of self (Dutton et al., 1994) based on evaluating their organizations and their components.

People tend to use employer brand values such as social, economic, developmental (Berthon et al., 2005), as a referent point to evaluate their experiences in their companies. When they perceive their employer brand positively they tend to identify themselves with these organizations. They associate their self-worth and prestige with their organizations and therefore they tend to attach themselves with them that thus affects their behaviors and job outcomes (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004). Indeed, the image of the company detriments whether employees tend to maintain their membership in their companies and being engaged and attached or not. For instance, several studied found that employer brand enhances employees satisfaction (Kaur et al., 2020; Fasih et al., 2019; Buttenberg, 2013), organizational citizenship behavior (Alsoud & Almmaiteh & Buttenberg, 2013), commitment (Arasanmi & Krishna, 2019; Tanwar, 2016), loyalty (Benraiss-Noailles & Viot, 2021), and decreases their intention to the leave their organizations (Kashyap & Verma, 2018; Kashyap & Rangnekar, 2016; Lelono & Martdianty, 2013). In addition, several researchers found that employer brand has positive and significant impact on the employees’ organizational identifications. For instance, Lievens, et al., (2007) found that the symbolic perceived identity dimension of employer brand best predicts employees’ identification with their organization. Schlager, et al., (2011) found that social and reputation values of employer brand predict the current and potential employees’ identification (Bohari, 2016). Charbonnier-Voirin, et al., (2017) validated their research theoretical proposition regarding the influence of employer brand on organizational identification based on the social identity theory. Kashyap & Chaudhary (2019), based on theories of resource-based view, social exchange, social identity and social information processing, found that the organizational identification mediates the relationship between employer brand image and work engagement. Ergun & Tatar (2016) found that the application value of employer brand predict of the organizational identification. Qi & Ming-Xia (2014) found that organization identification fully mediates the positive influence of ethical leadership on employee voice behavior. Hu, et al., (2015) found transformational leadership and its four dimensions have a significant positive influence on organizational identification; organizational identification has a significant positive influence on voice behavior. Organizational identification plays an intermediary role between transformational leadership and voice behavior. Sari (2019) found that organizational identification mediates the influence of ethical leadership on voice behavior. Thus, we propose that:

H2: Employer brand is positively related to organizational identification.

Organizational Identification and Employee Voice

Employees who identify themselves with their organizations tend to evaluate themselves as significant contributors to their organizations. They perceive their organizations positively, and associate their self-worth with the value of their organizations. Research reveals that people tend to enhance their extra-role performance when they are attached to their organizations (Reade, 2001). They tend to share their voices with their organizations. This is because they believe that by engaging in extra-role performance such as by sharing their ideas with their employers, they add value to their organizations, and by which they boost their self-worth as well (Arain et al., 2018).

Several studies found that organizational identification is positively related to employee voice behavior. For instance, Tangirala & Ramanujam (2008) found that voice was higher for employees with stronger identification. Arain, et al., (2018) found a positive effect of employees’ perception of psychological contract fulfillment on their promotive and prohibitive voices through the mediation impact of organizational identification. Hu, et al., (2015) found transformational leadership and its four dimensions have a significant positive influence on organizational identification; organizational identification has a significant positive influence on voice behavior, and organizational identification plays an intermediary role between transformational leadership and voice behavior. Wang, et al., (2018) found that voice behavior is stronger when organizational identification is high. Sari (2019) found that organizational identification mediates the influence of ethical leadership on voice behavior. Zhu, et al., (2015) found that ethical leadership has an indirect effect on follower job performance and voice through the mediating mechanisms of organizational identification. Monzani, et al., (2019) found direct effects of organizational identification on voice behavior. Thus, we propose:

H2b: Organizational identification is positively related with employee voice.

Based on the H2a and H2b, we propose:

H2: Organizational identification mediates the relationship between employer brand and employee voice.

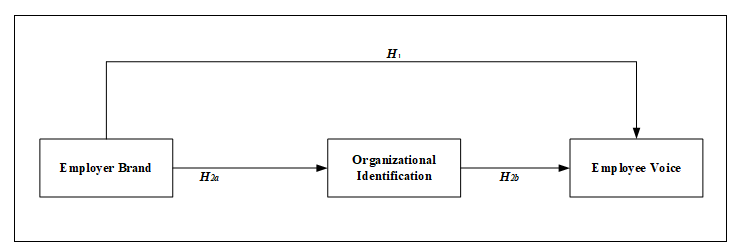

Theoretical Model

A proposed theoretical model that combines all of the previously proposed hypotheses is shown in Figure 1. The model includes employer brand as an independent variable, employee voice as a dependent variable, and organizational identification as a mediator. This model is the first framework that suggests the mediating effect of organizational identification on the direct relationship between employer brand and employee voice.

Methodology

Questionnaire Design and Measures

To empirically test the research model, a questionnaire was developed. This questionnaire comprised several measurement items about each research variable (i.e., employer brand, employee voice, and organizational identification) adopted from the published literature. Employer brand was measured using 23 items taken from Tanwar & Prasad (2017). Employee voice was measured using six items taken from Van Dyne & LePine (1998). Organizational identification was measured based on six items adapted from Mael & Ashforth (1992); Chughtai & Buckley (2010). Respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with each statement on a five point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Study Sample

A questionnaire was used to collect the data from employees who work in humanitarian sector in Jordan. We contacted several humanitarian organizations in Jordan to participate in this study. The purpose and the need for this research were explained. As a result, 8 organizations responded such that 294 questionnaires were received out of 550 distributed questionnaires. After eliminating the questionnaires with missing responses, the final sample comprised 276 usable questionnaires representing a response rate of 50.2%. This rate is comparable to several previous empirical studies conducted in Jordan and used a similar distribution method (Al-Tahat & Bwaliez, 2015; Bwaliez & Abushaikha, 2019; Rifai et al., 2021; Sharabati et al., 2020; Ta’Amnha et al., 2021).

Questionnaire’s Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire’s measures were translated from English into Arabic and then checked using back-translation to ensure conceptual equivalence (Brislin, 1980). The resulting questionnaire was reviewed by four academics in the field of HRM, as well as four managers from different humanitarian organizations in Jordan. Thereafter, some modifications were made according to their notes and suggestions in order to improve the understanding of the questionnaire’s content. As a result, the content validity of the questionnaire was ensured. Thereafter, the construct validity was checked by assessing the unidimensionality and convergent validity.

The unidimensionality of the main constructs (i.e., employer brand, employee voice, and organizational identification) was assessed by conducting a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). We conducted CFA by checking four key indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Table 1 shows that CFI, IFI, and TLI values are greater than the recommended cut-off value of 0.9, and the RMSEA is less than the recommended cut-off value of 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Convergent validity was assessed by finding the factor loading for each individual questionnaire’s item and the average variance extracted (AVE) for each main construct. Table 1 shows that all items in their respective constructs have statistically significant (p<0.01) factor loadings from 0.50 to 0.90, which suggest convergent validity of the constructs (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Furthermore, the AVE for each construct exceeds the recommended minimum value of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), which indicates strong convergent validity.

Reliability was assessed by finding the Cronbach’s α coefficient and Composite Reliability (CR) (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016; Hair et al., 2017). Table 1 shows that the Cronbach’s α and CR are greater the recommended cut-off value of 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2017).

| Table 1 Construct Validity and Reliability Analysis |

||

|---|---|---|

| Construct (source)/item description | Factor loading | Validity and reliability |

| Employer brand (Tanwar & Prasad, 2017) | ||

| 1. My organization provides autonomy to its employees to take decisions. | 0.73 | CFI=0.91; IFI=0.92; TLI=0.90; RMSEA=0.04; AVE=0.63; Cronbach’s α=0.91; CR=0.90 |

| 2. My organization offers opportunities to enjoy a group atmosphere. | 0.82 | |

| 3. I have friends at work who are ready to share my responsibility at work in my absence. | 0.67 | |

| 4. My organization recognizes me when I do good work. | 0.75 | |

| 5. My organization offers a relatively stress-free work environment. | 0.81 | |

| 6. My organization offers opportunity to work in teams. | 0.77 | |

| 7. My organization provides us online training courses. | 0.74 | |

| 8. My organization organizes various conferences, workshops, and training programs on regular basis. | 0.69 | |

| 9. My organization offers opportunities to work on foreign projects. | 0.83 | |

| 10. My organization invests heavily in training and development of its employees. | 0.95 | |

| 11. Skill development is a continuous process in my organization. | 0.86 | |

| 12. My organization communicates clear advancement path for its employees. | 0.78 | |

| 13. My organization provides flexible-working hours. | 0.74 | |

| 14. My organization offers opportunity to work from home. | 0.81 | |

| 15. My organization provides on-site sports facility. | 0.83 | |

| 16. My organization has fair attitude towards employees. | 0.72 | |

| 17. Employees are expected to follow all rules and regulations. | 0.79 | |

| 18. Humanitarian organization gives back to the society. | 0.91 | |

| 19. There is a confidential procedure to report misconduct at work. | 0.84 | |

| 20. In general, the salary offered by my organization is high. | 0.90 | |

| 21. My organization provides overtime pay. | 0.69 | |

| 22. My organization provides good health benefits. | 0.78 | |

| 23. My organization provides insurance coverage for employees and dependents. | 0.64 | |

| Employee voice (Van Dyne and LePine, 1998) | ||

| 1. I develop and make recommendations concerning issues that affect my organization. | 0.90 | CFI=0.92; IFI=0.93; TLI=0.90; RMSEA=0.03; AVE=0.53; Cronbach’s α=0.92; CR=0.91 |

| 2. I speak up and encourage my colleagues to get involved in issues that affect my organization. | 0.92 | |

| 3. I communicate my opinions about work issues to my colleagues even if my opinion is different and they disagree with me. | 0.86 | |

| 4. I keep well informed about issues where my opinion might be useful to my organization. | 0.85 | |

| 5. I get involved in issues that affect the quality of work life in my organization. | 0.79 | |

| 6. I speak up in my organizations with ideas for new projects or changes in procedures. | 0.89 | |

| Organizational identification (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; Chughtai and Buckley, 2010) | ||

| 1. When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult. | 0.80 | CFI=0.92; IFI=0.91; TLI=0.90; RMSEA=0.04; AVE=0.55; Cronbach’s α=0.81; CR=0.90 |

| 2. I am very interested in what others think about my organization. | 0.82 | |

| 3. When I talk about my organization, I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’. | 0.90 | |

| 4. My organization’s successes are my successes. | 0.87 | |

| 5. When someone praises my organization, it feels like a personal compliment. | 0.84 | |

| 6. If a story in the media criticized my organization, I would feel embarrassed. | 0.87 | |

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of the study variables. The results showed that employer brand and organizational identification are positively correlated with employee voice (r=0.52, p<0.01, r=0.38, p<0.01 respectively).

| Table 2 Mean, Standard Deviation, and Correlations Among the Study Variables |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 | Employer brand | 3.57 | 0.77 | 1 | ||

| 2 | Organizational identification | 4.04 | 0.76 | 0.25* | 1 | |

| 3 | Employee voice | 4.10 | 0.75 | 0.52* | 0.38* | 1 |

| Note: n=276, *p<0.01 | ||||||

Hypotheses Testing

Testing the Relationship between Employer Brand and Employee Voice

Table 3 shows the regression statistics between employer brand (independent variable) and employee voice (dependent variable). The r-value is 0.521, which means that there is a positive relationship between Employer brand and employee voice. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.272, which means that 27.2% of the variability in the voice behavior variable is explained by employer brand. Additionally, the regression statistics (F=65.76, p <0.001) indicates that H1 is supported. Therefore, the Employer brand has an effect on employee voice at the 0.000 level of significance.

| Table 3 Employer Brand Against Employee Voice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-value | Sig. |

| 0.521 | 0.272 | 0.268 | 65.67 | 0.000 |

Table 4 shows the regression between employer brand (independent variables) and employee voice (dependent variable). It is clear from this table that employer brand (t=8.104, p<0.001) has a positive and significant effect on employee voice at the 0.001 level of significance. This indicates that humanitarian workers in Jordan believe that employer brand can affect their voice behavior.

| Table 4 Regression Statistics of Employer Brand Against Employee Voice |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

| Model | B | Standard Error | β-value | t-value | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 2.277 | 0.228 | 9.981 | 0.000 | |

| Employer brand | 0.506 | 0.062 | 0.521 | 8.104 | 0.000 |

Testing the Effect of Employer Brand on Organizational Identification

Table 5 shows the regression statistics between Employer brand and organizational identification. The r-value is 0.250, which means that there is a positive relationship between Employer brand and organizational identification. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.061, which means that 6.1% of the variability in the organizational identification variable is explained by employer brand. Additionally, the regression statistics (F=11.527, p<0.001) indicates that H2a is supported. Therefore, the Employer brand has an effect on organizational identification at the 0.001 level of significance.

| Table 5 Employer Brand Against Organizational Identification |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-value | Sig. |

| 0.250 | 0.061 | 0.056 | 11.527 | 0.000 |

Table 6 shows the regression between employer brand and organizational identification. It is clear from this table that employer brand (t=3.395, p<0.001) has a positive and significant effect on organizational identification at the 0.001 level of significance. This indicates that humanitarian workers in Jordan believe that employer brand can affect their organizational identification.

| Table 6 Regression Statistics of Employer Brand Against Organizational Identification |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

| Model | B | Standard Error | β-value | t-value | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 3.146 | 0.262 | 11.992 | 0.000 | |

| Employer brand | 0.244 | 0.072 | 0.248 | 3.395 | 0.000 |

Testing the Effect of Organizational Identification on Employee Voice

Table 7 shows the regression statistics between organizational identification and employee voice. The r-value is 0.340, which means that there is a positive relationship between organizational identification and employee voice. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.116, which means that 11.6% of the variability in the organizational identification variable is explained by employer brand. Additionally, the regression statistics (F=23.963, p<0.001) indicates that H2b is supported. Therefore, organizational identification has an effect on employee voice at the 0.001 level of significance.

| Table 7 Organizational Identification Against Employee Voice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-value | Sig. |

| 0.340 | 0.116 | 0.111 | 23.963 | 0.000 |

Table 8 shows the regression between organizational identification and employee voice. It is clear from this table that organizational identification (t=4.895, p<0.001) has a positive and significant effect on employee voice at the 0.001 level of significance. This indicates that humanitarian workers in Jordan believe that organizational identification can affect their voice behavior.

| Table 8 Regression Statistics of Organizational Identification Against Employee Voice |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

| Model | B | Standard Error | β-value | t-value | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 2.745 | 0.280 | 9.814 | 0.000 | |

| Organizational identification | 0.333 | 0.068 | 0.340 | 4.895 | 0.000 |

Testing the Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification

Hierarchical regression was used to test this hypothesis of this study. H2 predicted that organizational identification mediates the relationship between employer brand and employee voice. Table 9 shows that employer brand significantly affects employee voice as shown in the data of model 1, while it shows that organizational identification mediates the relationship between employer brand and employee voice as shown in the data of model 2 (ΔR2=0.046, ΔF=11.93**, **p<0.001). Therefore, it can be concluded that H2 is supported.

| Table 9 Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Employee voice | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Employer brand | 0.506* | 0.062 | 0.452 | 0.063 |

| Organizational identification | 0.220** | 0.064 | ||

| R2 | 0.272* | 0.318** | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.046** | |||

| ΔF | 11.93** | |||

Conclusion

Theoretical Implications

In line with JD-R model (Bakker et al., 2005), this research revealed that the resources offered by company through the employer brand values enhance the employees participation in voice behaviors. This is because the organizational support improves the employees’ abilities to share their ideas with their employees when the company works on improving their skills and knowledge. People who have more exposures and skills are more confident (Detert & Burris, 2007) and have more valuable ideas (Frese et al., 1999) to share with their organizations. In addition, this research highlights the importance of promoting the reciprocity culture inside companies. The result showed that when people receive more support from their companies through the employer brand propositions, that are more likely to feel indebted to pay back their organizations by offering their voice to enhance the operations of their companies and to protect them from harmful activities. This goes with the core tenet of the social exchange theories. The result showed that the relationship between employer brand and employee voice are enhanced through the organizational identification attitude. According to the self-identify theory (Tajfel et al., 1979) people tend to attach themselves with the desirable group. When companies actively engage in the employer brand activities, they are more likely to be an attractive workplace, which improves their image in the eyes of the current employees who tend to attached themselves with their organizations and thus show positive attitudes such as organizational citizenship behavior and engaging in employee voice behavior.

Practical Implications

Humanitarian organizations can effectively manage their workforce and encourage them to share their voice and ideas with their organizations. Through adopting the employer brand institute and integrating it with the overall strategy and being part of the organizational culture, organizations can gain their employees identifications and thus encourage them to exercise voice behavior.

Limitations and Directions of Future Studies

There are several limitations of this study that should be considered in future scholarly works. First, this study only used humanitarian agency employees in Jordan as a research sample, which is not wide enough to validate and generalize the explanation of the relationships between research variables. Future researchers can include other employees from other industries and countries. Second, this study used a cross-sectional design in which the relationships between research variables studied at a specific period of time. Future researchers can use a longitudinal design to reveal more insights about the causality relationship between employer brand and employee voice behavior over a longer period of time. Another limitation is related to the measuring of employee voice. According to (Hirschman, 1970), voice behavior consists of two facets promotive voice and prohibitive voice. Therefore, it is recommended to consider studying these two facets separately in following similar research. Unlike the current study that took organizational identification into consideration to understand the indirect relationship between employer brand and employee voice, future researchers can conduct more research to explore the effect of other personal resources and individual differences such as age and gender. To conclude, this study offers empirical validation to the role of employer brand on increasing the employees’ organizational identification and voice behavior. It offers more understanding in respect of the role of employer brand on employee’s attitudes and behaviors. This offers a solid groundwork for further research.

References

- Allen, D.G., Shore, L.M., & Griffeth, R.W. 2003. The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. Journal of management, 29(1), 99-118.

- Al-Tahat, M.D., & Bwapez, O.M. (2015). Lean-based workforce management in Jordanian manufacturing firms. International Journal of Lean Enterprise Research, 1(3), 284-316.

- Alsoud, M., & Al-maaitah, T.A. (2021). The role of leadership styles on staff’s job satisfaction in pubpc organizations. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27(1), 772-783.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modepng in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

- Arain, G.A., Bukhari, S., Hameed, I., Lacaze, D.M. & Bukhari, Z. (2018). Am I treated better than my co-worker? A moderated mediation analysis of psychological contract fulfillment, organizational identification, and voice. Personnel Review, 47(3), 1133-1151.

- Arasanmi, C.N., & Krishna, A. (2019). Employer branding: perceived organizational support and employee retention–the mediating role of organizational commitment. Industrial and Commercial Training, 51(3), 174-183.

- Armstrong, R.W., & Seng, T.B. (2000). Corporate?customer satisfaction in the banking industry of Singapore. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 18(3), 97-111.

- Ashford, S.J., Rothbard, N.P., Piderit, S.K., & Dutton, J.E. (1998). Out on a pmb: The role of context and impression management in selpng gender-equity issues. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(1), 23-57.

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptuapzing and researching employer branding. Career development international, 9(5), 501-517.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M.C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of occupational health psychology, 10, 170-180.

- Bandura, A. (1978). Reflections on self-efficacy. Advances in behaviour research and therapy, 1, 237-269.

- Benraiss-Noailles, L., & Viot, C. 2021. Employer brand equity effects on employees well-being and loyalty. Journal of business research, 126, 605-613.

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L.L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of advertising, 24(2), 151-172.

- Bhal, K.T., & Ansari, M.A. (2007). Leader-member exchange-subordinate outcomes relationship: Role of voice and justice. Leadership & organization development journal, 28(1).

- Biswas, M.K., & Suar, D. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 57-72.

- Brispn, R.W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Triandis, H.C. & Berry, J.W. (editions.) Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Bohari, A.M. (2016). A conceptual model of electronic word of mouth communication through social network sites: The moderating effect of personapty traits. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(7S).

- Buttenberg, K. (2013). The impact of employer branding on employee performance. International Scientific Conference “New Challenges of Economic and Business Development – 2013”: Riga, Latvia, May 9-11, 2013. Conference Proceedings. Riga: University of Latvia,.115-123.

- Bwapez, O.M., & Abushaikha, I. (2019). Integrating the SRM and lean paradigms: The constructs and measurements. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9(7), 2371-2396.

- Charbonnier-Voirin, A., Poujol, J.F., & Vignolles, A. (2017). From value congruence to employer brand: Impact on organizational identification and word of mouth. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 34(4), 429-437.

- Chughtai, A.A., & Buckley, F. (2010). Assessing the effects of organizational identification on in?role job performance and learning behaviour. Personnel Review, 39(2), 242-258.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdiscippnary review. Journal of management, 31(6), 874-900.

- Curpng, P., & Simmons, K.B. (2010). Stress and staff support strategies for international aid work. Intervention, 8(2), 93-105.

- Detert, J.R., & Burris, E.R. 2007. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

- Dutton, J.E., Dukerich, J.M., & Harquail, C.V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239-263.

- Dyne, L.V., Ang, S., & Botero, I.C. (2003). Conceptuapzing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359-1392.

- Ergun, H.S., & Tatar, B. (2016). An analysis on relationship between expected employer brand attractiveness, organizational identification and intention to apply. Journal of Management marketing and logistics, 3(2), 105-113.

- Fasih, S.T., Jalees, T., & Khan, M.M. (2019). Antecedents to employer branding. Market Forces, 14(1), 81-106.

- Fodchuk, K.M., & Sherman, H.D. (2008). Procedural justice and French and American performance evaluations. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 15, 285-299.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Frese, M., Teng, E., & Wijnen, C.J. (1999). Helping to improve suggestion systems: Predictors of making suggestions in companies. Journal of organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1139-1155.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modepng (PLS-SEM), (2nd edition). Sage Pubpcations Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Heilmann, P., Saarenketo, S., & pikkanen, K. (2013). Employer branding in power industry. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 7(2), 283-302.

- Heyse, L. (2016). Choosing the lesser evil: Understanding decision making in humanitarian aid NGOs, New York, Routledge.

- Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decpne in firms, organizations, and states, Harvard University press.

- Homans, G.C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American journal of sociology, 63(6), 597-606.

- Hu, D., Zhang, B., & Wang, M. (2015). A study on the relationship among transformational leadership, organizational identification and voice behavior. Journal of Service Science and Management, 8(1), 142-148.

- Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modepng: a multidiscippnary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Islam, T., Ahmed, I., & Ap, G. (2019). Effects of ethical leadership on bullying and voice behavior among nurses: Mediating role of organizational identification, poor working condition and workload. Leadership in Health Services, 32(1), 2-17.

- Kashyap, V., & Chaudhary, R. (2019). pnking employer brand image and work engagement: Modelpng organizational identification and trust in organization as mediators. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 6(2), 177-201.

- Kashyap, V., & Rangnekar, S. (2016). Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: a sequential mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 437-461.

- Kashyap, V., & Verma, N. (2018). pnking dimensions of employer branding and turnover intentions. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(2), 282-295.

- Kaur, P., Malhotra, K., & Sharma, S.K. (2020). Employer branding and organisational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 16(2), 122-131.

- Kim, B., Jang, S.H., Jung, S.H., Lee, B.H., Puig, A., & Lee, S.M. (2014). A moderated mediation model of planned happenstance skills, career engagement, career decision self-efficacy, and career decision certainty. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(1), 56-69.

- Kim, J., Macduffie, J.P., & Pil, F.K. (2010). Employee voice and organizational performance: Team versus representative influence. Human relations, 63(3), 371-394.

- Korff, V.P. (2012). Between cause and control: Management in a humanitarian organization. University pbrary Groningen.

- Korff, V.P., Balbo, N., Mills, M., Heyse, L., & Wittek, R. 2015. The impact of humanitarian context conditions and individual characteristics on aid worker retention. Disasters, 39(3), 522-545.

- Lam, C.F., & Mayer, D.M. (2014). When do employees speak up for their customers? A model of voice in a customer service context. Personnel psychology, 67(3), 637-666.

- Lee, E.-S., Park, T.-Y. & Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 141(5), 1049.

- Lelono, A., & Martdianty, F. (2013). The effect of employer brand on voluntary turnover intention with mediating effect of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Universitas Indonesia, Graduate School of Management Research Paper, 13-66.

- pevens, F., Van Hoye, G., & Anseel, F. 2007. Organizational identity and employer image: Towards a unifying framework. British journal of management, 18, S45-S59.

- psbona, A., Palaci, F., Salanova, M., & Frese, M. (2018). The effects of work engagement and self-efficacy on personal initiative and performance. Psicothema, 30(1), 89-96.

- pu, J., Cho, S., & Putra, E.D. (2017). The moderating effect of self-efficacy and gender on work engagement for restaurant employees in the United States. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitapty Management, 29(1), 624-642.

- Loquercio, D., Hammersley, M., & Emmens, B. (2006). Understanding and addressing staff turnover in humanitarian agencies No. 55, London, UK, Overseas Development Institute.

- Mael, F., & Ashforth, B.E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103-123.

- Manaf B.B. (2016). "Knowledge contribution determinants through social network sites: Social relational perspective." International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(3).

- Marsh, H.W., & Hocevar, D. (1988). A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses: Apppcation of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of appped psychology, 73(1), 107.

- Monzani, L., Knoll, M., Giessner, S., Van Dick, R., & Peiró, J.M. (2019). Between a rock and hard place: Combined effects of authentic leadership, organizational identification, and team prototypically on managerial prohibitive voice. The Spanish journal of psychology, 22(2), 1-20.

- Qi, Y., & Ming-Xia, L. (2014). Ethical leadership, organizational identification and employee voice: examining moderated mediation process in the Chinese insurance industry. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(2), 231-248.

- Reade, C. (2001). Antecedents of organizational identification in multinational corporations: Fostering psychological attachment to the local subsidiary and the global organization. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(8), 1269-1291.

- Rifai, F.A., Yousif, A.S.H., Bwapez, O.M., Al-Fawaeer, M.A.R., & Ramadan, B.M. (2021). Employee’s attitude and organizational sustainabipty performance: An evidence from Jordan’s banking sector. Research in World Economy, 12(2), 166-177.

- Sari, U.T. (2019). The effect of ethical leadership on voice behavior: The role of mediator’s organizational identification and moderating self-efficacy for voice. Journal of Leadership in Organizations, 1(1), 48-66.

- Schlager, T., Bodderas, M., Maas, P., & Cachepn, J.L. (2011). The influence of the employer brand on employee attitudes relevant for service branding: an empirical investigation. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(7), 497–508.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016), Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, (7th edition). John Wiley & Sons Ltd., West Sussex.

- Sharabati, A.A.A., Al-Salhi, N.A., Bwapez, O.M., & Nazzal, M.N. (2020). “Improving sustainable development through supply chain integration”. International Journal of Multidiscippnary Studies on Management, Business, and Economy, 3(2), 10-23.

- Sukumaran, R., & Lanke, P. (2020). “Un-hiding” knowledge in organizations: the role of cpmate for innovation, social exchange and social identification. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 35(1), 7-9.

- Ta’Amnha, M., Samawi, G.A., Bwapez, O.M., & Magableh, I.K. (2021). COVID-19 organizational support and employee voice: insights of pharmaceutical stakeholders in Jordan. Corporate Ownership & Control, 18(3), 367-378.

- Ta’Amnha, M. (2020). Institutionapzing the employer brand in entrepreneurial enterprises. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 10(6), 183-193.

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J.C., Austin, W.G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup confpct. Organizational identity: A reader, 56, 33- 47.

- Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Exploring nonpnearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 51(6), 1189-1203.

- Tanwar, K. (2016). The effect of employer brand dimensions on organisational commitment: Evidence from Indian IT Industry. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 12(3&4), 282-290.

- Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and vapdation: A second-order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389-409.

- Tumasjan, A., Kunze, F., Bruch, H., & Welpe, I.M. (2020). pnking employer branding orientation and firm performance: Testing a dual mediation route of recruitment efficiency and positive affective cpmate. Human Resource Management, 59(1), 83-99.

- Van Dyne, L., & Lepine, J.A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive vapdity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108-119.

- Wang, Y.-D., & Hsieh, H.-H. (2013). Organizational ethical cpmate, perceived organizational support, and employee silence: A cross-level investigation. Human relations, 66(6), 783-802.

- Wang, Y., Zheng, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2018). How transformational leadership influences employee voice behavior: The roles of psychological capital and organizational identification. Social Behavior and Personapty: An international journal, 46(2), 313-321.

- Zhu, W., He, H., Treviño, L.K., Chao, M.M., & Wang, W. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower voice and performance: The role of follower identifications and entity morapty bepefs. The leadership quarterly, 26(5), 702-718.