Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 3

The Idiosyncrasy of Digital Platform Workers: An Investigation on how Socio-Psychological Elements help Gig Workers to Cope with Job Stress

Mano Ashish Tripathi, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology

Ravindra Tripathi, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology

Shekhar Saroj, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology

Uma Shakar Yadav, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology

Citation Information: Tripathi, M.A., Tripathi, R., Saroj, S., & Yadav, U.S. (2023). The idiosyncrasy of digital platform workers: an investigation on how socio-psychological elements help gig workers to cope with job stress. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(3), 1-12.

Abstract

Using insights from organisational psychology and studies of platform labour, this research investigates the ways in which platform employees' social and psychological environments shape their cognitive abilities and help them meet the challenges of their jobs. Based on a survey of 500 'riders' in the Indian food delivery industry, we provide quantitative evidence of employees' mixed subjective experiences, expanding on the mostly qualitative description within the context of previous research. We put to the test the complex interplay between job satisfaction, autonomy at work, confidence in one's own abilities, and a sense of personal well-being among employees. Research from our group shows that having social support from people like friends and family as well as online business interactions with colleagues significantly reduces rider stress. Our pattern of platform staff appears to be a method for them to draw on their internal and relational resources to achieve as an alternative an exceptionally high level of intellectual health, despite the well-documented instability and stress of platform work.

Keywords

Indian Gig Platforms, Gig Workers, Gig Economy, Meaningfulness, Mental Well-Being, Platform Work, Autonomy, Digital Work, Digital HRM.

Introduction

Two well-known gig economy digital platforms, Uber and Ola, are essential to the administration and organisation of an expanding workforce. Several government and consultant evaluations predict an increase in the number of people working under non-standard, short-term employment contracts in the future. The focus has switched to the academic literature from academic research that previously focused on company strategy and the changing labour relations in the gig economy The extensive algorithmic control that platforms have over their workers has drawn a lot of attention in the literature. Recent research from multiple studies has decisively shown that flexible employment disguises intensive management and unstable working conditions. Critical studies and media coverage of platform labour often portray the mental health of platform workers negatively, highlighting how precariousness and excessive algorithmic control have led to concern and stress in the workers. Given the growing attention given by academics and the general public to the topic of gig workers' livelihoods, it is surprising that so few studies have looked at the mental health of gig workers. A few recent research (e.g. Heiland, 2021) employed mixed-method study designs that included quantitative surveys to supplement qualitative results but did not enable rigorous, theory-based hypothesis testing (e.g. Heiland, 2021). In their poll, utilised one-item questions to gauge how food delivery staff felt overall about the platform (for example, "App is fair to me"). The consequences of many social and psychological factors on the wellbeing of platform employees at the micro-level are therefore unknown.

Precarity, Stress and Idiosyncratic Experience of Platform Workers

According to Karanovi and coworkers' definition of "platform work," this refers to the common practise of exchanging one's labour for financial gain through the use of online marketplaces, where temporary, task-based jobs are distributed by algorithms. Piecework has always been present in advanced economies, but the increased availability of digital labour platforms throughout the world has led to a rise in the casualization of the workforce. Due to unstable employment agreements and a competition for the lowest wages, platform employees are always on the lookout for new opportunities to supplement their meagre incomes (Griesbach et al., 2019). Malin and Chandler used the phrase "anxious work" to describe the state of mind some independent contractors find themselves in. Potentially compounding the emotional stress and worry of the typical platform worker is the instability of their job and the precarious financial situation in which they find themselves. Truthfully, this is the case. For instance, studies of people moving from rural areas to urban centres in India consistently use the descriptor "always feeling unsettled" (Wong et al., 2007). Algorithmic control via digital platforms is another major cause of stress that is frequently cited in the literature. Despite the fact that platform workers are often referred to as freelancers, the platform's algorithms are seen as the "boss" when it comes to managing this "decentralised" workforce (Möhlmannn et al., 2021). Platform employees are exposed to a wide variety of incentives and punishments under the watchful eye of the "algorithmic gaze" (Newlands, 2020). These algorithmic strategies may be summed up as the "6 Rs" by Kellogg et al. (2020): restricting and recommending activities, recording and evaluating employee performance, and rewarding and punishing undesirable employee actions. Due to the complexity of these systems, they may cause frustration, anxiety, and stress among workers. Taxi drivers and food delivery workers have it particularly tough, having to deal with the stresses of working in a complicated metropolitan environment while also adhering to strict deadlines and living in continuous fear of an accident (Gregory, 2021).

Critical studies on platform employment have highlighted the mental stress and anxiety faced by platform staff, in addition to the structural and technological challenges that contribute to their difficult working circumstances (Tripathi et al., 2022b). Recently, however, research utilising massive datasets have brought to light the complexity and nuance of workers' subjective experiences. According to an evaluation conducted by Berger et al. (2019) of 1001 London-based Uber drivers, while experiencing high levels of job-related anxiety, the drivers reported high levels of personal satisfaction. Broughton et al. (2018) found in their qualitative research of 150 UK gig workers that part-time gig employees have lower stress levels than full-time gig workers (2018). Additional study has indicated that the lived experiences of gig workers are marked by mixed feeling. According to a multi-platform research, while the workers' overall liberating feeling of "not having to answer to anyone" ensures their consent, it also effectively assures their own exploitation. Employees at Ola, on the other hand, often follow a Neoliberal and Entrepreneurial ethos and are generally favourable toward the computational methods used by the company. She is curious to learn more about how it operates.

Winning their hearts and minds is the key to controlling the workforce (p. 360). It would thus be simplistic to portray a generic image of the mental strain that platform employees experience while studying the many labour issues that arise in platform employment. According to de Vaujany et al. (2021), "joy lived among sorrow, inspiration alongside frustration, pleasantries beside the worried" best describes the subjective experience of workers (p. 687).

The available literature doesn't seem to include any studies on the complexity of platform workers' mental states, which were previously reported. In this article, we expand on the idea that people who work in the platform economy, like their counterparts in more traditional organisations, may cope with stress by drawing on a wide range of inner resources and outer forms of social support (relational resources). We speculate on the relationships between platform employment and the three dimensions of well-being (finding one's work meaningful, feeling competent in one's profession, and feeling emotionally and mentally healthy) Tripathi et al., 2022a; (Tripathi et al., 2022c). Because the impact dimension's survey questions are tailored to more conventional types of employment in which workers are entitled to a voice in and influence over the organization's most important strategic and decision-making processes, we opted to exclude it (Matthews et al., 2003). Due to the nontraditional character of platform employment and the overrepresentation of rural migrants in the food delivery industry, we decided against include the subscale in our study (i.e., not measuring what the scale intends to measure). As a replacement for "empowerment," we utilised the word "active orientation" to express the theoretical position of the research. Empowerment, according to Maynard et al. (2012), is a wide notion that includes both individual and societal elements.

Giving one's job significant value can offer one a feeling of purpose or meaning in life. Workers are more likely to be intrinsically driven when they feel their work has meaning, even if their duties itself aren't pleasurable. The findings of organisational psychologists suggest (Rosso et al., 2010; Shamir, 1991). Platform workers don't have easy access to information emphasising the value of their labour. Freelancers would be fools to think platform jobs are anything but mundane.

As a result, we state that,

H1. Meaningfulness of work is positively associated with platform workers' job satisfaction (H1a) and negatively associated with mental strain (H1b).

When someone has self-efficacy, they believe they can follow out a plan of action and get the outcomes they want (Bandura, 1977). According to multiple research, workers who are more certain of their abilities are less likely to experience workplace stress. We believe that the self-evaluated competence of platform workers is comparable to that of employees in conventional organisations. This is likely to have an impact on two things: workplace happiness and mental health. Literature on platform workers' self-efficacy is few, with just a few studies noting the importance of "know-how" and "social skills" in ride-hailing services and the ability of delivery couriers to design optimal routes in urban locations (Chan, 2019). However, it is logical to expect that a platform worker with experience and expertise is more likely to love their work:

H2. Self-competence is positively associated with platform workers' job satisfaction (H2a) and negatively associated with mental strain (H2b).

"Autonomy" is defined as an individual's sense of control over his or her job in organisational psychology, which is similar to "self-determination" (Spreitzer et al., 1997). A feeling of work autonomy is substantially correlated with job satisfaction and wellbeing, according to earlier research It is widely accepted in the corporate world of today that giving workers some degree of autonomy over their job promotes productivity, engagement, and satisfaction. The freedom to choose one's own schedule and plan one's own work, according to many platform workers, is the main draw for choosing gig labour over regular employment. Employees' top priority seems to be autonomy, according to large-scale studies of gig workers. It follows those platform employees who see their job as highly autonomous can anticipate positive emotional experiences similar to those of their coworkers in normal employment:

H3. Autonomy is positively associated with platform workers' job satisfaction (H3a) and negatively associated with mental strain (H3b).

A person's social support network is an external resource that may be drawn upon when internal resources like purpose, competence, and autonomy are depleted. In times of stress, having friends and family around to lean on for advice and comfort may be invaluable. For the sake of their mental health, gig economy and independent workers need access to tailored social support. Gig workers are particularly vulnerable since they receive no official or informal support from platform businesses (Yadav et al.,20022a). Social isolation among migrant workers in India is mostly caused by employment instability and economic disparity, according to a recent study. Employees require a social support network of their own to help them deal with stress, anxiety, and the challenges of daily living. A central tenet of social support theory is the "stress buffering hypothesis," which proposes that people's informal networks of friends and family can act as a protective barrier against the negative psychological and physiological consequences of stress. For this reason, the stress-buffer system modifies one's outlook on the situation and mitigates the stress experienced as a result of the perception of readily available personalised social support. Our natural inclination is to conclude:

H4. Personalised social support of platform workers is negatively associated with their mental strain.

To investigate these hypotheses, we conduct a large-scale study of Indian employees on food delivery platforms. Next, we'll give you a rundown of the research's context and methods.

Empirical Context and Methods

One of the fastest-growing economic sectors in India is the gig economy, which is supported by internet platforms. According to a working paper from the International Labour Organization, platform workers in India made up 10.1% of all employment in 2019. (Zhou, 2020). About three million riders will be working for Zomato, the biggest meal delivery service in India, in 2020, delivering 27 million food orders each day on average to clients throughout the nation (Ye, 2021). Similar to its Western equivalents, Indian labour platforms organise interactions between the platforms, the employees using it, and the consumers who use it in a triangle-shaped pattern (Franke & Pulignano, 2021). Due to their position as a market intermediary, platform businesses may choose to classify their personnel as independent contractors rather than as directly recruited employees, therefore avoiding the requirements of employee rights and benefits regulations. Similar to how Uber manages its staff in the United States, platform companies in India utilise automated systems for job assignment, monitoring, rewards, and punishment (Sun, 2019). The procedure is largely the same for Indian food delivery couriers and their western counterparts: an order submitted via an online platform is assigned to a specific rider based on his or her present geographic location, among other factors. If that rider accepts it, the platform algorithm generates a suggested route and starts tracking the rider's movements. The total performance of the rider is determined by a set of algorithmically determined factors, including as delivery speed, on-time delivery percentage, and customer ratings. See Wu and Zheng for a thorough explanation of how Indian food-delivery platforms control their riders' spatiotemporal mobility and daily schedules (2020).

Measurement Instrument Development

There are a total of four sections to the survey questionnaire. In the first section, employees are asked three questions concerning their overall experiences in the workplace, such as whether or not they are content with their current job and salary (Pugh, 2011). In Section 2, we look at how to measure workers' active orientation using markers like self-efficacy and autonomy. These specifications are based on the original plan created by Spreitzer (1995). The worker's offline and online social contacts, as well as the number and quality of each, are explored in Section 3. The final questionnaire was developed utilising measures from previous studies on social networks conducted both traditionally and digitally.

The GHQ-12, a 12-item general health questionnaire, is used in the study to gauge levels of emotional strain. Originally developed for use in psychiatric diagnostics, the GHQ-12 has found widespread application in studies of subjective health and happiness in the fields of social science and medicine. Multiple country-wide studies use it, with the British Household Panel Survey being a notable example (BHPS). Studies on Indian migrant workers have made use of and verified the use of GHQ12 variants. By responding to 12 questions, each on a 4-point scale, an individual's well-being index may be calculated (ranging from 0-36).

Three academic experts who were not part of the study team reviewed a preliminary version of the survey questionnaire.. In addition, 10 students from an Indian university helped us double-check the survey's translation into Indian and determine the typical time needed to complete it. After that, it was altered to improve the survey's flow and eliminate any ambiguous phrasing.

Data Collection

We distributed the questionnaires to food delivery platforms workers in Mumbai and Delhi. Despite Mumbai being on India's most developed coast, Delhi has sizable communities of migrant workers. To conduct the poll, we only utilised websites and mobile apps. The research company sent out the survey invites after randomly selecting 500 commuters from the two sites, then assessed the responses to make sure the required sample size and variance were satisfied.

Behavioural analytics and other attention filters were used to weed out responses of questionable quality. Automatically disqualified were responses that could be written in under five minutes and duplicates from the same IP address. We also had the research firm verify the uniformity of the responses. If a responder chooses "Strongly Agree" to both "In general, I do not enjoy my work" and "All in all, I am content with my employment," the survey will be deleted.

One hundred randomly selected riders from each city were used to test the survey's effectiveness. We performed a PCA in R on the pilot data set to investigate the instrument's dimensionality. All of the factor loadings for the latent variables were greater than 0.60, and the cross-loading values were also higher, with the exception of one item assessing the Meaning construct. Since the Indian translation was imperfect, we opted to keep the Meaning item (= 0.539) after making some changes to the language. In August and September of 2020, the primary poll will get an extra 400 replies (200 from each of the cities of Mumbai and Delhi). All of the aforementioned quality assurance procedures allowed us to study the data extensively and turn up no unexpected results. Accordingly, we selected 400 data points (N = 400) for the basic data analysis shown below.

Data Inference and Results

The GHQ-12 index, which is strongly skewed to the right (skewness = 0.668), was used to quantify the amount of severe stress experienced by workers in our sample (mean = 9.235, SD = 5.263). Less than 25 percent of individuals who completed the exam had a score of 12 or above, which might point to potential issues with one's wellbeing (Lundin et al., 2016). On a scale of one to five, about 75% of respondents rated their work as highly pleased, with a mean rating of 4.158 and a standard deviation of 0.549. In our sample, 65% of respondents (mean = 3.996, SD = 0.680) scored a 4 or above, suggesting that they had discovered meaning in their work. While the majority of respondents (mean 4.250, SD = 0.580) thought they were extremely skilled in their field, they also agreed or strongly agreed (72.8 percent, respectively) that they had a lot of autonomy in their job.

When it came to individualised social support, the majority of respondents maintained frequent contact with family members and participated in online social contacts. More than two-thirds of those surveyed indicated they spoke with family at least once a week (34.8%) or every day (1.0%). (33.8 percent). They reportedly engaged in an average of six chat groups every day and had an average of 176 Whatsapp/Facebook accounts (mean = 176.23, median = 142.50, minimum = 36, maximum = 670). On the internet, one-on-one and group chats are often used.

Measurement Scale Evaluation

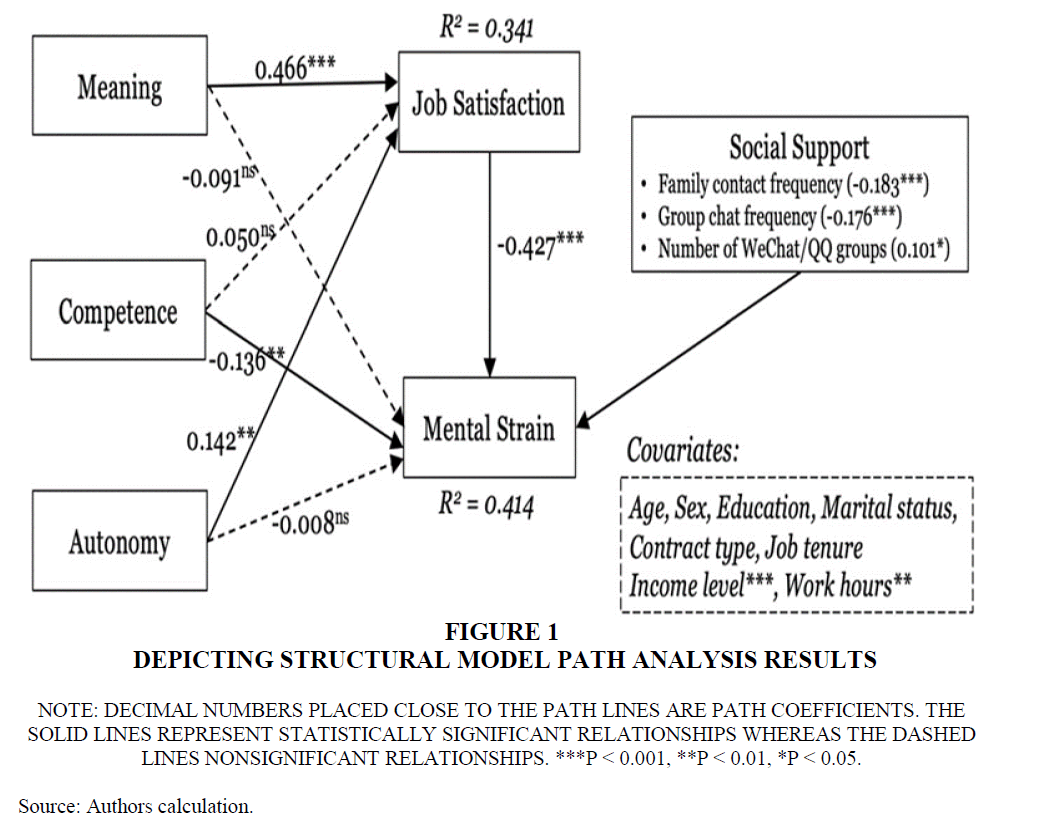

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to examine the convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of the scale. The R package lavaan (https://lavaan.ugent.be/) was used. All items in the latent variable had loadings below 0.5 on the primary construct. Cronbach's alpha and the Jöreskog's kappa were used to determine the instruments' reliability. Jöreskog's results were between 0.85 and 0.91, whereas ours were between 0.75 and 0.89, demonstrating high reliability (see Figure 1). If the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) is bigger than the correlations between the variables, then the AVE has strong convergent and discriminant validity.

Figure 1 Depicting Structural Model Path Analysis Results

NOTE: Decimal numbers placed close to the Path Lines are Path Coefficients. the Solid Lines Represent Statistically Significant Relationships whereas the Dashed Lines Nonsignificant Relationships. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Source: Authors calculation.

Our survey methodology included a three-item marker variable titled "attitude toward the colour blue" to identify CMB. We originally tested the structural model (described below) without the marker variable before deciding to introduce it as an exogenous construct. When the marker was incorporated into the model, there was no change in the significances of the individual routes. We also compared CMB to a single-factor CFA model using the single-factor CFA test established (Craighead et al., 2011). The real measurement model did not fit well with the one-factor model. Our findings suggest that the CMB does not pose a serious threat to our data.

Hypothesis Testing

This model was estimated in ADANCO 2.2 with all variables represented as reflecting variables in order to analyse the structural pathways and assess the hypotheses (Figure 1). By using Baron and Kenny's mediation analysis, we looked at how job satisfaction may play a part in our model (1986). For starters, we looked at the direct connections between Mental Strain and the exogenous variables (Meaning, Competence, and Autonomy), and we discovered that only the connection between Competence and Mental Strain was statistically significant (p 0.01). We then tested whether or not there was a correlation between levels of competence and contentment in the workplace; this finding was weak (p = 0.339). Therefore, it seems reasonable to infer that this model provides no evidence of meaningful mediation.

It display the outcomes of our hypothesis tests. Happiness at work and mental fatigue are inextricably linked; this is common knowledge. Meaning (= 0.466, p 0.001) and Autonomy (= 0.142, p 0.01) are positively connected with Job Satisfaction, however Competence is not associated (= 0.050, p = ns) with any of the three active orientation categories. Although Job Satisfaction has a negative connection with Mental Strain, only Competence has a statistically significant negative link with Mental Strain (= 0.136, p 0.01).

The most significant social support indicators were how often people communicate with their family (= 0.183, p 0.001), how often they participate in group chats with coworkers (= 0.176, p 0.001), and how many Facebook and QQ groups they visit (= 0.101, p 0.05). There is no correlation between social network size (numbers of new, close, and overall friends) and online activity (browsing, commenting, and posting on Facebook), and this is true for all types of social support.

While working hours are positively connected with mental strain (= 0.120, p 0.01), job satisfaction is strongly correlated with income (= 0.284, p 0.001). No statistically significant correlations between Job Satisfaction and Mental Stress and other demographic and employment-related variables were found (sex, age, education, and marital status).

Discussion

The purpose of this research is to learn more about the emotional health of platform employees and the methods they use to deal with stress. Based on our examination of the facts, we have come to the following three conclusions: Perceptions of purpose and control at work are related to higher levels of job satisfaction and psychological health. Despite the well-documented difficulties of working on a food-delivery platform, employees often report high levels of well-being.

By organising these core findings and other pertinent observations inside a model-based framework, we are better able to convey these and other exciting discoveries to the wider scientific community (job satisfaction and mental strain).

Sociologists and labour economists have debated labor's significance for decades. The subject of whether or not platform employees feel their jobs have any significance has not been examined by many scholars, despite the rising scholarly interest in their work (Yadav et al.,20022b) More than half of Indian food delivery employees surveyed said they enjoy their employment. The organisational psychology literature outlines a number of mechanisms by which doing work that one finds meaningful can improve their subjective well-being. These mechanisms range from reducing the negative effects of work stress to allowing a person's positive emotions to carry over into their personal life. Our data modelling shows that working on a platform may help alleviate mental stress by making one happier in their employment.

This research highlights the significance of platform work and its effect on workers' psychological well-being. Due to widespread short-termism, food delivery drivers are less likely to build a professional identity or follow a professional "calling," in contrast to self-employed creative workers (Petriglieri et al., 2019) or company owners (Stephan et al., 2020). Based on previous research (Broughton et al., 2018) Despite this, there is a dearth of literature on the subject of how platform employees in the service industry evaluate their own worth. Because they are able to provide for their families financially while still making a living, there is some evidence that Uber drivers and delivery couriers feel a sense of purpose in their work. It's possible that rural Indians have an especially strong desire to work in cities and send money home to their families. Zheng and Wu (2022) recently conducted a study in which other Indian food delivery employees likewise said things like, "At the end of the day, I'm doing this for my family—my wife and kids." There is compelling evidence that working as a food delivery worker is essential, given the positive association between pay and job satisfaction.

Idiosyncratic Experience of Autonomy

These findings lend support to the "suggestive correlations" between platform workers' level of independence on the job and their level of satisfaction with their jobs. In our research on food-delivery couriers, we found evidence that the much-touted independence of platform labour really affects worker happiness. Given the evidence in the literature, it's not surprising that gig workers in both Western and Global South contexts value the freedom they gain from their employment. It's important to note that while studies have indicated a link between job satisfaction and lower stress levels, no correlation was established between greater levels of autonomy and better psychological health. Some people think that autonomy at work may have both positive and negative effects on people's mental health. Based on the responses to our poll, emotions might not be completely transparent. Several qualitative studies have found that the freedom to choose one's own schedule and lack of micromanagement are major factors contributing to workers' "enjoyment" on platforms. Skeptics, on the other hand, point out that the phrases "freedom" and "flexibility" may also entail having to take on more responsibility for one's life and experiencing financial instability, all of which can lead to increased concern and emotional exhaustion. This study's finding of no correlation between worker autonomy and mental health adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the complexity of this concept. Self-perceived competence in India food delivery has a negative effect on mental health but has no connection to work satisfaction. It seems sense that highly proficient riders should experience less stress, but it's interesting to note that there is no connection between self-competence and job satisfaction. According to organisational psychology studies, competency is often a significant predictor of job pleasure in the service business. We hypothesise that the absence of a relationship between self-competence and job satisfaction in our data is a result of the widespread belief that food delivery work is a low-skilled occupation with little to no entry criteria. Our results show that platform employees are unlikely to feel fulfilment in successfully performing delivery tasks since the labour is seen as low-end and fundamental in nature. Wu and Zheng (2020) have noted in their study that you'll need a lot of cognitive talents, creative thinking, and tacit knowledge if you're looking to optimise your income by utilising the platform's algorithmic restrictions. The degree of stress experienced by migrant employees is directly correlated with their capacity to do their tasks with high levels of efficiency. Unlike purpose and autonomy, which have an indirect influence on mental health through impacting work satisfaction, self-competence has a direct impact on mental health.

Social Support for an Atomised Workforce

Social networking applications like Facebook may assist today's migrant workers avoid social isolation and build psychological resilience, similar to how playing video games at Internet cafés in India helped them unwind in the 2010s. When we looked at how social media affected the stress levels of food delivery riders, we found mixed findings. The positive effect on one's psyche that some have reported from participating in online group chats is more evidence that finding virtual community among those going through similar experiences can be therapeutic. However, increasing your involvement in online groups won't do anything to alleviate your stress. We hypothesise that riders' mental health improves only when they use social media to have real-time conversations with friends and family or in small groups. Our data shows that the size of one's social network and the frequency with which one engages in asynchronous Facebook activities (such as reading and commenting on friends' posts) are not reliable measures of social support. Actively engaging with friends on social networking sites, as opposed to merely following and browsing, is the sole predictor of good emotions of well-being, as shown by Verduyn et al. (2017) in their critical analysis of the impact of social networking sites on subjective well-being.

Even if there are numerous options to engage with friends and strangers online, family interaction is still a significant source of social support for motorcyclists. In our study, we discovered a strong link between increased family engagement and less mental stress. It is concerning because riders mostly depend on family bonds for social support while friends both online and offline don't seem to matter much. In normal commercial organisations, there is little mentoring or collegiality to assist employees manage stress and create a feeling of community. Instead, platforms for gig employment are created to encourage atomized working relationships and push employees against one another in an attempt to compete for jobs. The previously mentioned inter-worker competition is exacerbated by the income-focused connotation (Yadav et al.,20022c). Precarious contracts and structurally disembedded living situations also threaten platform workers' social and normative foundations. In their attempts to "disrupt digital atomization," as some have put it, platform staff seem to be becoming more unified and close-knit (Heiland & Schaupp, 2021). In the past, researchers have looked at "platform cooperativism" and workers' social media groups on both the micro- and macro-levels. Although prior research has mostly focused on individual resistance and collective action (or lack thereof) against platforms, workers' social resources have a broad variety of consequences for their mental wellbeing. Peer communication is becoming more and more important in an atomized workforce as a consequence of the high frequency of group chats as well as the large negative association between chat frequency and mental strain. To this end, our study adds to the growing corpus of research showing that platform employees may benefit from mental support from coworkers by using digital communication technologies. It is hard to envision a broad-based Indian labour movement that extends beyond daily demonstrations and spectacular mobilizations due to the lack of political will and high levels of job satisfaction observed in our research.

Gig Workers Dilemma of Indifferent Experience

In contrast to previous studies, we found very low levels of mental stress in our sample of migratory Indian labourers using the GHQ-12. Based on 2008 surveys, Akay et al. (2014) found that the average GHQ-12 score of migrant workers was 28.47, whereas Zhong et al. (2013) found that Indian migrants had greater psychological distress than the overall population. It is unknown what variables have led to the improvement in the mental health of Indian migrant workers, despite new ethnographic study questioning the mainstream narrative. Wages and long hours are the biggest culprits, according to studies on the causes of mental stress among Indian factory employees. Long hours and heavy workloads, low pay, and delayed compensation were the top three sources of stress for these worker. In the job paradigm of the gig economy, each of these requirements is greatly reduced. Our sample of riders averaged daily shifts of 8-10 hours, which is less than the normal workday for someone in a workplace or café.. The high earnings potential, minimal skill requirements, and instant cash received after each delivery have made food-delivery platforms a popular alternative for migrants.Our most recent surveys and ethnographic studies suggest that the mental health of India platform workers has improved over the last several years. We think that this advantageous change has been facilitated by the structure of the platform-based gig job paradigm. Food delivery platform labour is risky and exploitative, but it also provides higher pay and benefits than conventional low-skill jobs, which were a big cause of stress for migrant workers from India.

Conclusion and Future Research

In order to better understand the issues impacting the mental health of Indian platform gig workers, this study draws on literature from a variety of fields. We present quantitative data to supplement the literature's primarily qualitative portrayal of emotional ambivalence among platform employees and refute the generalisation that poor mental health is a consequence of their precarious employment (e.g., worry and stress) A statistical model based on Spreitzer's concept of organisational empowerment looks at and assesses micro-level sociopsychological aspects of the workforce rather than concentrating on macro-level structural disadvantages and algorithmic managerial practises. Our findings reveal that employees of Indian food delivery platforms enjoy a high degree of mental health as a direct result of their access to and utilisation of personal and social support systems. In an effort to test a model, this study ignores relevant variables that may affect platform employees' personal and professional fulfilment. Individual elements, such as personality traits, are examined, as they pertain to the topic of professional self-management. There is some evidence that these variables are associated with lower levels of job satisfaction and other objective measures of well-being. According to research conducted by Goods et al. (2019) on food delivery couriers in Australia, a person's level of satisfaction with their profession is greatly influenced by their socioeconomic "fit." More complicated social networks may have a role in the career choices and job happiness of platform employees if future study focuses on the "fit" between work and life. Removing the effect variable from Spreitzer's original model was based on a careful analysis of how well the measuring scale would perform in China's setting and not a denial of platform employees' potential to affect change. Nonetheless, there is a need for more study into the various types of resistance taken by Indian gig workers, which may lead to increased self-confidence and happiness. Our sample size is small even though it is quite accurate because there are millions of people who use public transportation in China's major cities. The results of the two surveys suggest that users in China's secondary cities may have a very different platform-use experience than those in China's major cities. Therefore, we hypothesise that rider satisfaction is generally high, despite a dearth of data on dissatisfied former riders. A longer-term research that follows working people in different areas over time may provide a more nuanced picture. Given the widely acknowledged instability and pressures of the modern workplace, we believe this study contributes to our understanding of the personal experiences and social support systems of platform employees. We'd want to see an expanded toolkit of research methods used to probe platform employees' perceptions on digital and physical platforms for employment.

References

Akay, A, Giulietti, C., Robalino, J. D., & Zimmermann, K.F. (2014). Remittances and well-being among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(3), 517-546.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berger, T., Frey, C.B., Levin, G., & Danda, S.R. (2019). Uber happy? Work and well-being in the ‘gig economy’. Economic Policy, 34(99), 429-477.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Broughton, A., Gloster, R., Marvell, R., Green, M., & Martin, A. (2018). The experiences of individuals in the gig economy.

Chan, N.K. (2019) “Becoming an expert in driving for Uber”: uber driver/bloggers' performance of expertise and self‐presentation on YouTube. New Media Society, 21(9), 2048–2067.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Craighead, C.W., Ketchen, D.J., Dunn, K.S. & Hult, G.T.M. (2011) Addressing common method variance:guidelines for survey research on information technology, operations, and supply chain management. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 58(3), 578–588.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Franke, M. & Pulignano, V. (2021) Connecting at the edge: cycles of commodification and labour control within food delivery platform work in Belgium. New Technology, Work and Employment.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Goods, C., Veen, A. & Barratt, T. (2019) “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform‐ based food‐delivery sector. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 502–527.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gregory, K. (2021) “My life is more valuable than this”: understanding risk among on‐demand food couriers in Edinburgh. Work, Employment and Society, 35(2), 316–331.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Griesbach, K., Reich, A., Elliott‐Negri, L. & Milkman, R. (2019) Algorithmic control in platform food delivery work. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 5, 237802311987004.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Matthews, R.A., Michelle Diaz, W. & Cole, S.G. (2003) The organizational empowerment scale. Personnel Review, 32(3), 297–318.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maynard, M.T., Gilson, L.L. & Mathieu, J.E. (2012) Empowerment—Fad or fab? A multilevel review of the past two decades of research. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1231–1281.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Möhlmannn, M., Zalmanson, L., Henfridsson, O. & Gregory, R. (2021) Algorithmic management of work on online labor platforms: when matching meets control. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 45(4), 1999–2022.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pugh, S. D., Groth, M., & Hennig‐Thurau, T. (2011). Willing and able to fake emotions: A closer examination of the link between emotional dissonance and employee well‐being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 377–390.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosso, B.D., Dekas, K.H. & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010) On the meaning of work: a theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shamir, B. (1991) Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies, 12(3), 405–424

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spreitzer, G.M. (1995) Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tripathi, M. A., Tripathi, R., Yadav, U. S. & Shastri, R.K, (2022a). Gig Economy: Reshaping Strategic HRM In The Era of Industry 4.0 and Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Positive School Psychology,6(4) ,3569-3579.

Tripathi, M. A., Tripathi, R., & Yadav, U. S. & Shastri,R.K, (2022b). Gig Economy: A paradigm shift towards Digital HRM practices. Journal of Positive School Psychology,6(2), 5609-5617.

Tripathi, M. A., Tripathi, R., & Yadav, U. S. (2022c). Identifying the critical factors of physical gig economy usage: A study on client’s perspective. International Journal of Health Sciences, 6(S4), 4236–4248.

Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Maxime, R., John, J. & Kross, E. (2017) Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well‐being? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 274–302.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wong, D.F.K., Li, C.Y. & Song, H.X. (2007) Rural migrant workers in urban China: living a marginalised life. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(1), 32–40.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wu, P.F. & Zheng, Y. (2020, June 15). Time is of the essence: spatiotemporalities of food delivery platform work in China. ECIS 2020 Proceedings. European Conference on Information Systems, Marrakech, Morocco.

Yadav, U. S., Tripathi, R., & Tripathi, M. A. (2022a). Adverse impact of lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic on micro-small and medium enterprises (Indian handicraft sector): A study on highlighted exit strategies and important determinants. Future Business Journal, 8(1), 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yadav, U. S.,Tripathi, M. A., Tripathi, S. & Tripathi, R.(2022b) Impact of lockdown during covid- 19 pandemic on micro small and medium enterprises (with special reference to indian handicraft sector): a study on determinants and exit strategies. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(S1), 1-13.

Yadav, U.S, Tripathi, R., Tripathi, M.A., & Kushwvaha, J. (2022c). Performance of women artisans as entrepreneurs in odop in uttar pradesh to boost economy: strategies and away towards global handicraft index for small business. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(1), 1-19.

Ye, J. (2021) China moves to protect food delivery drivers from digital exploitation. South China Morning Post.

Zhong, B.‐L., Liu, T.‐B., Chiu, H.F.K., Chan, S.S.M., Hu, C.‐Y., Hu, X.‐F. et al. (2013) Prevalence of psychological symptoms in contemporary Chinese rural‐to‐urban migrant workers: an exploratory meta‐analysis of observational studies using the SCL‐90‐R. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(10), 1569–1581.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhou, I. (2020). Digital Labour Platforms and Labour Protection in China

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 20-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-13041; Editor assigned: 21-Dec-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-13041(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Jan-2023, QC No. AMSJ-22-13041; Revised: 11-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-13041(R); Published: 16-Mar-2023