Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

The Evolution from Pre-Academic Marketing Thought to the New Paradigm of Entrepreneurial Marketing

Cosmas Anayochukwu Nwankwo, University of KwaZulu-Natal

MacDonald Isaac Kanyangale, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Citation Information: Nwankwo, C.A., & Kanyangale, M.I. (2022). The evolution from pre-academic marketing thought to the new paradigm of entrepreneurial marketing. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(2), 1-15.

Abstract

With resource scarcity and increasing competition, entrepreneurs are struggling to find an entrepreneurial way of marketing for their enterprises to survive and grow. While the evolution of marketing practice and thought informs them about the past paradigm shifts, it is less insightful on the contemporary or future paradigm of marketing needed to survive in the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment. The objective of this article is to critically understand the shifts in marketing thought and marketing practice and ultimately propose the birth of a new paradigm of marketing. The article is valuable as it provides an integrative perspective of the various shifts in marketing thought and practice in the past, but also illuminates the nature, approaches and core elements of entrepreneurial marketing as a potential future paradigm of marketing. Without the phenomenon of entrepreneurial marketing, the extant notion of the evolution of marketing thought and practice is incomplete but also not contemporary.

Keyword

Evolution of Marketing, Marketing practice, Marketing thought, Entrepreneurial Marketing.

Introduction

The old paradigms in the evolution of marketing practice and thought are less helpful for the entrepreneurial marketer to respond to the contemporary challenges in the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) business world. Most of the prevailing notion of marketing lack entrepreneurial and innovative orientation. Traditionally, we talk of marketing as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” (American Marketing Association, 2017). There is a plethora of similar definitions of marketing within the traditional paradigm that one can easily categorise them into three distinct groups all of which miss the entrepreneurial and innovative orientation. These groups reflect (1) marketing as a process of linking the producer with the market through a marketing channel, (2) marketing as a philosophy or concept of business, and (3) marketing as an orientation, directed at both the consumer and producer experience, which enables them exchange offerings of value. Recently, the pursuit of marketing activities with an entrepreneurial mind-set is becoming pivotal for the entrepreneur or owner-manager, especially that this focuses on introducing rather than reacting to change (Toghraee et al., 2017). Over the years, marketing philosophies, concepts, thoughts and techniques used by marketing practitioners and entrepreneurial marketers have evolved through a variety of periodic paradigm shifts. In an attempt to explore the evolution of marketing practice and thought, it is fundamental to ensure scholarly clarity of the meaning of paradigm shift. Kuhn (1962), the American physicist and philosopher introduced the notion of paradigm as the set of concepts and practices that define a scientific discipline at any particular period of time. For the purpose of this article, there are three fundamental issues related to paradigm which are insightful to explore the evolution of marketing practice and thought (Kuhn, 1962). First, paradigm is about what members of a certain scientific community have in common and embrace techniques, ideas, concepts, theories and shared values (Kuhn, 1962). Secondly, the dominant paradigm define what members of a discipline believe is possible and rational to do, giving scholars and practitioners a clear set of tools to approach certain problems at a particular time (Kuhn, 1962). In Greek, paradigm means example of or the framework for a given knowledge domain (e.g. science, humanities, marketing) and discipline and field (Blessinger et al., 2018). Thirdly, a paradigm shift occurs when enough significant anomalies accrue against the dominant paradigm (Kuhn, 1962). Thus, a paradigm shift is characterised by radical change in the core concepts and practices of a given domain, discipline or field such as marketing (Kuhn, 1962). When a paradigm shift occurs, the worldview that previously dominated the domain is altered or even replaced with a new worldview (Blessinger et al., 2018). While the concept of paradigm shift originated in science, it has permeated numerous non-scientific contexts including marketing. The question of what paradigm is currently informing entrepreneurial marketers and how it is linked to previous paradigms of marketing thought and practice is interesting.

The aim of this article is to discuss the paradigmatic changes in marketing thought and practice over the years and ultimately illuminate the birth of a new marketing paradigm and its core aspects which is likely to shape the future of marketing. The article is valuable to scholars of marketing as it does not only integrate pre-academic marketing thought and variety of fundamental changes in marketing practice, but also illuminate the core elements of entrepreneurial marketing as an emerging future paradigm in the domain of marketing. This article begins by discussing the evolution of marketing practice, and marketing thought which is followed by a focus on the new paradigm of entrepreneurial marketing (EM).

Review of Literature

Evolution of Marketing Practice

In general, practice may refer to “the done thing, in both the sense of accepted as legitimate and the sense of well-practiced through repeated doing in the past” (Whittington, 2002). Jarzabkowski & Wilson (2002) explicitly note that practice differs from practices which are the “ingrained habits or bits of tacit knowledge” comprising the activity system. In this way, the evolution of marketing over the years may be revealed at this micro-level of the activity system. In essence, “practice relates to the logic, which transcends a variety of contexts and has explanatory power derived from practices across different micro-level contexts within organisations” (Jarzabokowsk & Wilson, 2002). Practice in this article focuses on activities by firms which reflect marketing activities and interactions. In this vein, there is no interest in practice-related issues such as who is the practitioner, what resources do they draw upon as well as the distinction between practices, practice or praxis (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007). The term marketing practice which became popularly used in the nineteenth century describes the commercial activities of buying and selling products and/or services (Jones & Tadajewski, 2016). Marketing theorists describe marketing practice in terms of eras, philosophies and orientations and/or concepts of marketing (Blythe, 2005; Kotler & Keller, 2016). Notably, marketing practice resonates with the work of Kotler & Keller (2016) who view the evolution of marketing in terms of five distinctive concepts namely: production concept, product concept, sales concept, marketing concept, the concept of holistic marketing and green/sustainable marketing (Kotler & Keller, 2016). It is instrumental to delve into the core idea and practice encapsulated by each concept, and unearths what had prompted the transition from one concept to the next until the contemporary paradigm of marketing.

Production Concept

The scholarly starting point in exploring shifts in the marketing practice hinge on the production concept which is considered as the oldest business approaches. There are three fundamental aspects of the production concept. First is the assumption that consumers prefer products which are available and cheap (Kotler & Keller, 2016). To this end, all activities are centred on the efficient manufacturing of larger quantities of a product at a lower cost. Efficiency and effectiveness of business processes, cost control and technology are very central in the production concept. Second, the customer is usually relegated to the background (Armstrong & Kotler, 2015). Concisely, the production concept manifests an inward focus whereby the customer was placed at the periphery (Ndubisi, 2016). A very good example of this classic concept is Henry Ford's statement regarding the production of the Model T. In emphasising efficiency and the reduction of costs Ford, in response to one of his manager’s suggestion that the Model T be produced in a greater variety of colours, famously commented: “Give them the colour they want, provided it is black” (Coax, 2015). The central logic in the production concept lies in conditions which include demand exceeding supply and difficulties with availability of a desired product (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). Between 1800 and 1950, the production concept was characterised by an inward focus (Kotler & Keller, 2016). The practice of marketing, when viewed in the context of production, presents two critical issues: its relevance to the contemporary business world and its use in organisations. Firstly, this concept is considered as a practice which originated in the last century and is less useful with the contemporary opening up of markets and globalisation as products are more accessible. Secondly, it is very tempting to believe that the production concept is exclusively relevant to large contemporary organisations and not small and medium enterprises. This may be true if one subscribes to the view that many organisations lack resources to gain economies of scales which arise from the production concept of marketing. On the other hand, some scholars, including Ndubisi (2016), argue that it is this very lack of resources which compel organisations to produce standardised products, thus paying little heed to flexibility and specific customer needs. The paradox thus lies in whether organisations have stagnated at the production concept or whether they have moved with the times to adopt contemporary marketing practices. As mass production capacity and lower pricing become inadequate to meet the needs of some customers, quality and performance of the product itself signals a need for a shift in marketing practice.

Product Concept

The second shift in marketing practice hinge on product concept, characterized by a focus on product innovation, superior quality and performance which exceeds the basic functional requirements of the product (Kotler & Keller, 2016). One of the key tenets of the shift to product concept was the need for marketing activities to focus on the company’s internal capacity to create and assure product quality as the basis for achieving higher margins and placed less emphasis on the principles of economies of scale. In pursuit of product concept, enterprises were adopting continuous improvement to enable them set higher prices than their competition (Kotler & Keller, 2016). It is decipherable that both the product concept and production concept adopt an inside-out rather than a market-led approach. However, the danger with the product concept is that it may be viewed as a fallacy or “better mousetrap” (Kotler & Keller, 2016). It is possible that marketing management can be misguided. Often the superior quality and performance of products may convince customers to buy a product while the importance of other elements of marketing, such as distribution and promotion, may be forgotten (Ndubisi, 2016). In the product concept, there is increasing recognition that defining and determining quality by firms is not easy as this entails on-going market research and customer research which requires skills and resources.

Sales Concept

The third shift in the marketing practice centred on moving from product to sales orientation. The sales concept was based on the premise that to achieve sales objectives, it is not enough to manufacture a product and allow customers to make a choice at their own discretion (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). Instead, sales and promotional activities, which offer various incentives, methods, sweepstakes, direct contacts and promotional messages, direct the customer to choose one specific product above another (Ndubisi, 2016). The core idea of sales practice is best summarised by Sergio Zyman, former marketing manager of the Coca Cola Company, who asserted that the aim of marketing is to sell more goods, to more people, more often and for more money (Zyman, 2002). Viewed through this inside-out prism, Coca Cola has been successfully selling products to the world for years by implementing sales and promotional activities and placing its strategic focus on activities which facilitate the sale of its products.

However, selling practices have been criticised for not being based on the needs of customers but rather the pushing of products on the basis of internal capacities and opportunities for manufacturers. In other words, the primary focus is on setting and achieving sales targets for the company through effective sales skills, geographic organisation and intensive distribution. This failure to focus on customer needs is not exclusive to the sales concept but can be found in the product and production concepts as well. In the small enterprises, sales practice can have a variety of implications. Firstly, many small enterprises lack dedicated resources especially that of an effective and skilled sales force, to develop the practice of forecasting and setting realistic sales targets (Ndubisi, 2016).

Marketing Concept

The fourth shift in marketing practice hinge on the marketing concept. There are three key issues in the marketing concept. First, the marketing concept reflects a shift from production-oriented activities to customer-oriented activities, where the customer is considered king (Kotler & Keller, 2016). The active relationship between a firm, consumers and their needs is called the marketing concept. In the marketing concept, facilitating long-term and sustainable success of firms is pivotal for doing business in sophisticated markets with sophisticated customers. In an older article entitled “Marketing Myopia”, Levitt (1960) posits that railroads in the United States of America (USA) collapsed not because there were no passengers or cargo, but because the needs of the customers were not considered or were addressed by other means such as cars, trucks, airplanes and even telephones. The railway companies in the USA thus lost customers as they viewed themselves as being in the railroad business rather than the business of meeting the transportation needs of passengers and cargo. In short, the railway companies incorrectly defined their industry as railroad-oriented instead of transportation-oriented because they were product rather than customer-oriented (Levitt, 1960). The marketing concept does not only imply a commitment to the firm’s strategic thinking and an analysis of changes in the business environment but also a consideration of the organisation’s mission and capabilities (Sharp, 1991). The practice of marketing concept emphasizes on identifying consumers’ wants and needs and consequently satisfying them (Skripnik, 2017). Second, the marketing concept is characterised as unique for its outside-in approach to marketing activities and the market as a whole (Kotler & Keller, 2016). However, one should note that “concepts in which firms begin their operations from their own internal capabilities and goals are not successful in markets where competition is strong and where the consumer has readily accessible information and a variety of offers” (Ndubisi, 2016). Third, there is the assumption that consumers are aware of all their wants and needs. This assumption in marketing is sometimes erroneous as latent needs are sometimes identified, and demand is subsequently stimulated for needs which consumers did not even know they had (Kotler & Keller, 2016). As such, the marketing concept upholds the view that some customer needs are created and communicated to customers rather than simply discovered by the marketer.

The Societal Marketing Concept

The fifth shift is the societal marketing which surfaced in the 1970s. Notably, the paradigm shift from marketing concept to societal marketing is a response to flagrant, indulgent consumerism and unethical business practices. The practice of societal marketing is driven by three main concerns. These are the concern for human welfare, or what is in the best interest of people; consumer needs, and not just wants; and lastly, profit generation through the building of long-term customer relationships (Ndubisi, 2016). Societal marketing is cognizant that a conflict exists between society’s long-term interests and consumers’ short-term wants. In this regard, enterprises cultivate marketing practices which ensure long-term societal and consumer welfare (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). Notably, the practice of societal marketing did not surface until when the impact of business activities on society and the environment became more pronounced. Societal marketing embrace the task of determining the needs, wants and interests of target markets and delivering the desired satisfactions more effectively and efficiently than competitors in a way which preserves, or enhances, the consumer’s and society’s well-being (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). Thus, societal marketing considers not only ways in which to satisfy the market and generate profit, but also still reduce the negative effects on environment. The shift to societal marketing underscores the need to not only incorporate the customer in product decisions but also in decisions which impact the immediate environment. Socially responsible behaviour of firms is central in societal marketing. Concisely, societal marketing opposes the claim by Friedman (1970) that “the social responsibility of business is to make profit”. The notion of societal marketing underscores that market orientation promotes business survival. The philosophy of societal marketing underscores that priority is accorded to social concerns. In a different vein, social marketing is also construed as a separate business concept which is complementary to the adoption of marketing concept (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018).

Holistic Marketing Concept

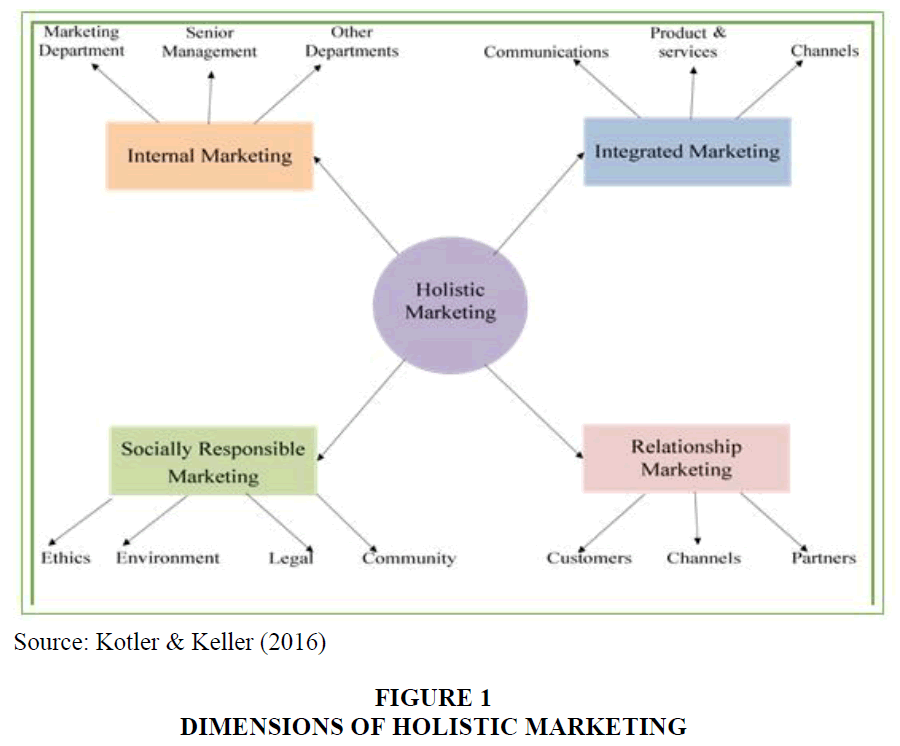

The sixth shift in marketing is evident in the 21st century, showing a transition from societal to holistic marketing (Kotler & Keller, 2016). Holistic marketing concept surfaced in reaction to changes in the business environment. The key rationale of holistic marketing was to surmount inefficient traditional ways of customer-centred marketing and to formulate a new unified method that could respond to dynamic needs in a more comprehensive and innovative way (Kotler & Keller, 2016). The four components that characterise holistic marketing are: relationship marketing, internal marketing, integrated marketing and socially responsible marketing (Kotler & Keller, 2016). These components are represented in Figure 1. To reflect the full variety of activities which constitute this marketing practice, each of these components is explained briefly as follows.

Firstly, relationship marketing as a component of holistic marketing focuses on building long-term relationships between customers, employees, marketing partners (channel partners, supplier/s and agencies) and members of the financial community (capital owners, investors and analysts) on the one hand and companies on the other hand (Ndubisi, 2016). This relationship is defined, in part, by the way in which two or more people or things are connected or behave towards each other. The organisational dimension of relationship reflects the connection of an organisation to stakeholders, including customers (Ndubisi & Nwankwo, 2012; Yulisetiarini, 2016). This underscores the ideas that marketing may not be simply considered as transactional but rather relational in nature. As such, marketing practitioners were focusing on creating long-term relationships with customers to enhance repeat purchasing, rather than merely focusing on marketing activities leading to an immediate sale (Kotler et al., 2019). Relationships consist of several episodes or series of interactions between parties and are also characterised by various stages with progression from initiation through maintenance to enhancement or termination (Nota & Aiello, 2019). The extent to which a relationship yields profitable exchanges and meaningful connections between parties is critical in gauging the quality of the relationship from a marketing point of view (Nota & Aiello, 2019). Initiating, maintaining and enhancing relationships which affect the success of marketing activities, either directly or indirectly, are key to holistic marketing. Intensified customer care fosters long-lasting relationships which deliver better return-on-investment (ROI). In the digital era, organisations are using social media as part of their digital marketing strategy to spread brand awareness, generate sale leads and enhance engagement with customers (Hemann & Burbary, 2018). Digital marketing refers to the measurable, targeted and interactive marketing of goods, or services, using digital technologies to reach and convert leads into customers and preserve them (Ndubisi, 2016). Through the use of technology, small businesses could target specific types of people based on location, interests, behaviour, demographics and/or connections with enhanced personalisation. However, organisations need to be aware of possible disadvantages of digital marketing which, in Africa, include: difficulties resulting from slow internet connections, distrust of electronic methods of payment and users’ distrust based on prolific fraud regarding virtual promotions. Internet marketing has not yet been adopted by all business people, particularly the old, who still harbour a distrust of digital environment and prefer using conventional ways.

Secondly, integrated marketing is another dimension which characterizes holistic marketing. Integrated marketing has the ability to connect a firm’s marketing activities and/or programmes to thus enhance customer value. This process increases value in a way that would not have been possible had the individual programmes and/or activities been simply added together (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). Kotler & Keller (2016) maintain that marketers traditionally rely on the concept of the 4Ps (product, price, place and promotion) marketing mix. This process affords guidance as to the variety and/or scope of marketing activities which need to be integrated to meet customers’ needs. One weakness of integrated marketing activities is that they tend to focus on the seller’s experience rather than that of the customer (Kotler & Armstrong, 2018). To facilitate a shift of focus and place the customer’s experience at the centre, Lauterborn (1990) suggests that the 4Ps (product, price, place and promotion) model be replaced with that of the 4Cs (communication, convenience, customer cost and customer solution).

Thirdly, holistic marketing also includes internal marketing. This component refers to the recruiting, training and motivating of employees to profitably serve their customers. Employees in the organisation, particularly those at senior management level, appreciate and acknowledge the principles of marketing as the driver of business. Generally, the implementation of internal marketing depends on the development of human resources management through improved labour productivity and employee satisfaction (Catalin et al., 2014). Internal marketing has the potential to enable employees to make a significant emotional connection with the products being sold and/or the services being offered. Without this connection, employees are likely to undermine the expectations set by the advertising unit and stakeholder communication.

Lastly, socially responsible marketing is also considered a key component to holistic marketing. Socially responsible marketing, as noted before, is built on the assumption that the effects of an organisation’s marketing activities are felt outside the organisation and, consequently, affect customers and society as a whole. A clear understanding of the context and business environment in which marketing activities are carried out is key to socially responsible marketing. This component of holistic marketing addresses a variety of aspects including: environmental concerns, ethical conduct as well as the legal and social perspectives of marketing activities and programmes. One of the key criticisms of the holistic marketing concept is that it focuses mainly on marketing functions and, as such, does not consider other activities of the firm. All four components of holistic marketing (socially responsible marketing, relationship marketing, internal marketing and integrated marketing) are primarily considered as marketing activities. In that way, they do not relate to other organisational activities which are non-marketing but key for business such as production, management style and general organisational culture (Keelson, 2012). Paradigm shift from holistic marketing to sustainable marketing invoked debate on whether holistic marketing was an authentic new concept or merely an expansion of the marketing concept (Dončić et al., 2015). Other scholars, such as Armstrong & Kotler (2015) were figuring out how holistic marketing was not only different but better than the concept of societal marketing, as discussed earlier.

Green/sustainable Marketing Concept

The seventh shift in marketing practice is the turn to green marketing which emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s to minimise the environmental hazards caused by the industrial manufacturing and to strengthen corporate eco-centric image in the consumers’ perception of products (Kumar, 2017). According to the American Marketing Association (2017) green marketing which is often called ecological marketing is described as “an approach in marketing of products that is mainly focused on environmental safety; it incorporates business activities which consist of packaging modification, production process, and green advertising”. Green marketing is also referred to as environmental green marketing and sustainable green marketing which affects every aspect of the marketing mix (Yan & Yazdanifard, 2014). Kumar (2017) maintained that green marketing is an integrated management process responsible for identifying, forecasting and satisfying the needs of customers and society, in a profitable and sustainable way. To become a sustainable firm, Kotler & Keller (2016) stress that firms must employ resources and the marketing mix in such a way that it can serve humans needs in the long run. The question of technological use and its evolution is central to green enterprises which is characterised by a focus on reduced use of energy in production, reduced consumption of natural resources, reduced emission of gas and toxic material into the environment and reduced creation of waste from the manufacturing of green products (Kumar, 2017). Kotler & Keller emphatically affirm, if the objective of integrating green concerns into marketing practice is to help achieve environmental sustainability, it is profound that marketing activities move away from conventional processes. In this regard, it is critical that the responsibility for marketing should not only be limited to internal operations, but rather be expanded to stakeholders outside the organisation as well e.g. within society and environmental groups. Therefore, going green is no longer considered a cost of doing business; it is a catalyst for innovation, wealth creation and new market opportunities for organisations. The holistic marketing and green/sustainable marketing concept, as highlighted by Kotler & Armstrong (2018) as well as Kumar (2017), reflect upon the latest marketing approaches which were developed to address the fundamental changes in the environment such as demographic changes, climate change and resource scarcity, globalisation, hyper-competition, internet development and environmentalism, to name but a few.

The effort to understand the evolution of marketing practice in terms of conceptual evolution is insightful but suffers from two major pitfalls. First, it only focuses on the evolution of modern schools of thought on marketing. Thus, it is incomplete because it excludes the traditional school of marketing (e.g. commodity school, institutional school) evident in pre-academic marketing thoughts. Second, the notion of sustainable marketing is facing the deficit of not being entrepreneurial to guide entrepreneurial marketers in a VUCA. To enrich our understanding of the evolution of marketing, it is therefore important to also delve into the periods of marketing thoughts or eras.

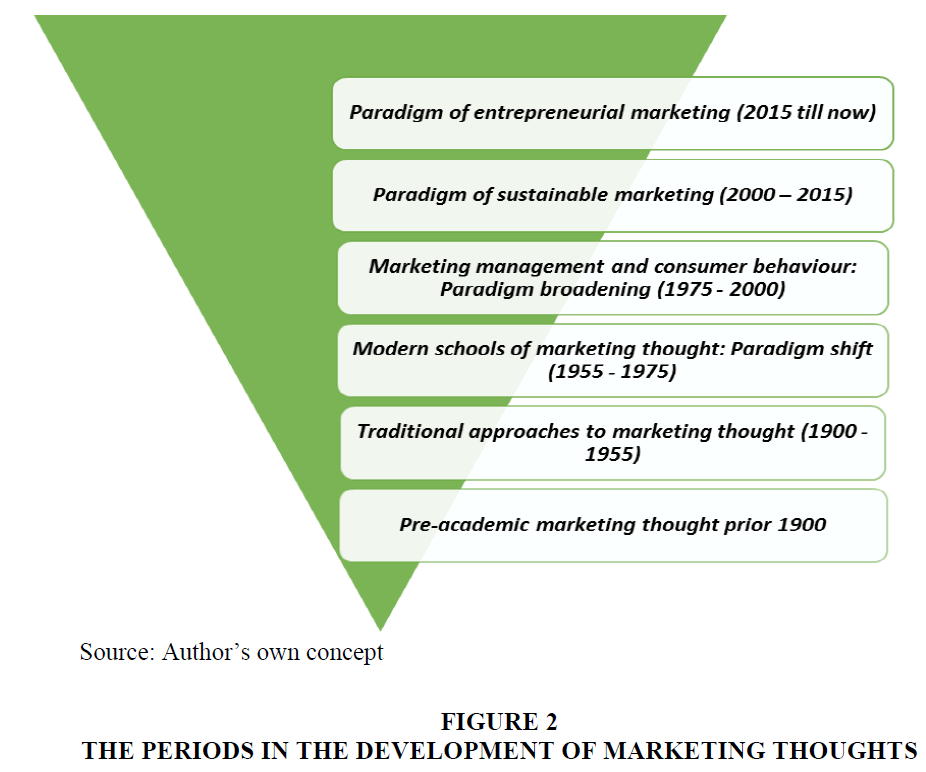

The Periods in Unpacking Marketing Thoughts

Different scholars, such as Bartels (1965), Wilkie & Moore (2003) as well as Shaw & Jones (2005), have delved into the evolution of marketing thought. Based on the comprehensive works of Bartels (1965), Wilkie & Moore (2003), the paradigmatic shifts in marketing thoughts are presented in Figure 2 and discussed below.

Pre-Academic Marketing Thought Prior 1900

It is notable that pre-academic marketing thought begun before 1900. This is the first era characterised by macro-marketing issues such as the way in which marketing was amalgamated into society. The macro-view of marketing dates back to the ancient Greek Socratic philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato (Shaw, 1995). According to Jones & Shaw (2006), much has also been written about how micro-marketing can be practiced ethically. At this time many scholars agreed that marketing, as an academic discipline, could be considered a branch of economics namely applied economics. Several schools of economic thought, particularly the Classical and Neoclassical schools (Martins, 2015) and the German Historical and American Institutional schools (Jones & Monieson, 1990), contributed to the development of marketing science during this time. However, the emancipation of this school of thought carved the way for the emergence of traditional marketing. Commonly, this aspect in the evolution of marketing is often omitted, making our understanding incomplete.

Traditional Approaches to Marketing Thought (1900 - 1955)

The second period, from 1900 to 1955, reflected the development of traditional or conventional approaches to marketing thought. The early 20th century saw businesses in the United States and some developed countries flourish which led to a massive migration of people from rural communities to cities as well as the emergence of free mail and package delivery services. This period is also characterised by the rise of national brands and chain stores and newspaper and magazine advertising. There was expansion of transport networks and options which linked rural farmers (through brokers, agents and allied producers) with intermediary traders and wholesalers with vendors. As a result, small specialty stores could eventually reach consumers as well as the national mail order houses and new giant department stores (Shaw & Jones, 2005). These changes demanded fundamental change in market distribution systems.

The three marketing approaches were: the commodity school, which focused on different kinds of commodities in the marketplace and how they were promoted and distributed, the institutional school, which highlighted middleman functions and channel flows or intermediaries in the marketing of goods and services and the functional school, which adopted a systems approach to marketing and focused on marketing attributes as well as the identification of marketing functions and systems. A major criticism of this period is that it placed too much stress on the functionality and institutionalisation of marketing thought.

Modern Schools of Marketing Thought: Paradigm Shift (1955 - 1975)

The third period, from 1955 to 1975, marks a paradigm shift from traditional marketing approaches (the marketing functional approach, commodity approach, institutional approach and consumer behaviour approach, amongst others) to modern schools of marketing thought (service marketing, relationship marketing and green marketing, amongst others). When the World War II ended, marketing thought was influenced by not only military achievements (e.g. in mathematical modelling, linear programming) but also the shift in capacity from military production to consumer goods which inspired economic progress in the United States (Alderson & Miles, 1965) and created supply surpluses. At the fore of the forces invoking paradigmatic change was the need to seriously think about activities which would help to generate or stimulate consumer demand.

Marketing Management and Consumer Behaviour: Paradigm broadening (1975 - 2000)

The fourth period, from 1975 to 2000, is referred to as paradigm broadening. In this period, various academics active in other disciplines (particularly psychology), began to take a keen interest in the marketing discipline yielding different kinds of empirical studies including those which focused on consumer behaviour (Sheth, 1992). Kotler (1972), Kotler & Zaltman (1971) and Kotler & Levy (1969) were among the major scholars in regaining the lost glory of the marketing discipline. This drive led to the creation of three schools of marketing namely: marketing management, exchange and consumer behaviour.

Marketing management guides a firm's marketing plan. In the marketing management school, the emphasis is using market information which is mostly acquired, in a systematic method, through research and surveys. A thorough knowledge of the firm's current market, the setting of realistic goals and targets, the development of new market penetration strategies as well as the implementation of effective marketing plans within budget are all part of marketing management (Ndubisi, 2016). In short, marketing management is a business element which creates and expands an institution's marketing plan. Exchange, on the other hand, is the act of obtaining a desired object from someone by offering something in return (Armstrong & Kotler, 2015). With this definition, it is important to note that the exchange process covers both relationship marketing and other marketing activities. Therefore, with relationship marketing, firms tenaciously view the long-term relationship alongside their target audience. The aim is to grow their business through delivering customer value and constantly cultivating the relationship with their customers. Furthermore, consumer behaviour is the study of how individual customers, groups or organisations select, buy, use and dispose of ideas, goods and services to satisfy their needs and wants (Ndubisi, 2016). It refers to activities of customers in the marketplace as well as the underlying intentions to performing said activities. Marketers presume that attaining knowledge about what precisely prompts consumers to buy particular products would help them to determine which products are obsolete, or needed, in the marketplace as well as how to best present said products to consumers.

Paradigm broadening has expanded the scope of marketing thought by facilitating its gradual growth from its original conventional orientation on business activities to a wider view which covers all kinds of human activity linked to generic and/or social exchange.

Paradigm of Sustainable Marketing (2000-2015)

The fifth period, in which the paradigm of sustainable marketing is at work, was first identified in the early 21st century and has progressed until around 2015. Sustainable marketing, as a concept, focuses on environmental and social demands, eventually turning them into competitive advantages by delivering value and satisfaction to customers (Belz & Binder, 2017). Mindful of the triple bottom line at the core of the phenomenon of sustainability, sustainable marketing may be defined as building and maintaining sustainable and profitable relationships with customers as well as the social and natural environment (Ndubisi, 2016). Furthermore, a wide view of sustainable marketing suggests that it focuses on the adoption of sustainable business practices to create better businesses, better relationships and a better world (Rudawska, 2018). In view of these notions, one would say that sustainable marketing is broader than green marketing as it represents the guiding principle of sustainability. The ability of organisations to efficaciously use sustainable marketing to support their business plan/s for gaining sustainability is grounded in their environmental and social sensitivity. Environmental challenges, such as global warming, resource exhaustion, disposal of toxic waste and landfill management, are problems with far reaching public as well as legislative impact. As a result of such developments, firms have become eco-centric. It is vital that green values be structured into a new paradigm which acknowledges the interconnectedness of humankind and the planet and which views this relationship as part of sustainable development. This means that green marketing must readdress its thinking in such a way that it becomes sustainable marketing.

Paradigm of Entrepreneurial Marketing (2015 Till Now)

A new paradigm called EM is emerging at the crossroads of two distinct disciplines of entrepreneurship and marketing. Notably, both the field of marketing and entrepreneurship share two key elements which are core to the paradigm of EM. First, they hold customers as their principal focus and require the entrepreneur to assume some level of uncertainty and risk. Second, they share the importance of identifying opportunities and operating in a constantly changing environment. Concisely, Toghraee et al. (2017) illuminates that EM is nontraditional marketing which is often insightful in proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities, acquiring and retaining profitable customers by adopting innovative approaches in the managing of risk, leveraging resources and creating value in a resource-constrained but also VUCA context. The nature of EM shows that decisions do not often rely on formal planning process, as marketing strategies are emergent and adjusted at the time of implementation. Arguably, entrepreneurial marketers do not always behave in a rational and sequential manner. Instead, they are immersed in the market to have a thorough understanding of the problem their customers are facing and to identify solutions that customers seek (Kilenthong et al., 2015).

According to Hills & Hultman (2011), the first academics to unite the fields of entrepreneurship and marketing were Tyebjee and Murray in the early 1980s. These scholars claimed that entrepreneurs partake in numerous activities vital to the marketing theory. A different version ascribes the origin of EM to Professor Gerald Hills who organised the first entrepreneurship and marketing conference in 1982 whilst asserting that marketing is a critically important part of entrepreneurship. Contrary to this, some marketing scholars such as John et al. (1999) maintain that EM started in the early 1980s as a result of changes in the domain of marketing organisation which included strategic alliances, globalisation and technology. Arguably, marketers focused on superficial and transitory whims of customers, and were preoccupied with the tendencies to imitate instead of innovation. The growth in scholarly regarding EM started to rise across the globe in 2015, with this in mind; there is a need for clarity of two fundamental issues, namely the approaches and key ontological dimensions of EM as a paradigm of marketing.

Three Approaches to EM

The three key approaches to EM which are attracting scholarly attention are termed the integrated, process and imbalanced approaches. Firstly, the integrated approach seeks to integrate essential entrepreneurial and marketing attributes, giving rise to a unique paradigm which stretches beyond either entrepreneurship or marketing (Toghraee et al., 2017). This approach uphold that EM is non-linear, unplanned and embraces the visionary marketing activities of the entrepreneur or owner-manager. Advocates of this view include Morris et al. (2002) who define EM as “proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities for acquiring and retaining profitable customers through innovative approaches to risk management, resource leveraging and value creation”. This definition exemplifies the integration of the rudiments of entrepreneurship (innovativeness, opportunity, proactivity and risk taking) with marketing as a medium to create customer value (customer focus, guerrilla marketing, resource leveraging and value creation). However, the challenge in the integration approach to EM is the question of which aspect of the two (entrepreneurship or marketing) is considered dominant in the ontology of EM.

Secondly, the process approach upholds EM as an individual or organisational process. For example, Hills & Hultman (2011) consider “EM as a complex process as well as an orientation for how entrepreneurs behave in the marketplace”. Thus, EM is considered as a marketing process initiated by a founder with an entrepreneurial attitude. Other scholars do not focus on the individual but rather on the organisational level of the EM process. For instance, Kraus, Harms and Fink (2010) define “EM as an organisational function and a set of processes for creating, communicating and delivering value to customers and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit the organisation and its stakeholders and that is characterised by innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and may be performed without resources currently controlled.” Entrepreneurial marketers are thus not defined by available resources, but pursue opportunities in the belief that the necessary resources can somehow be obtained. Hacioglu et al. (2012) as well as Kraus et al. (2010) hold the view that EM remains a process, irrespective of whom, when and how the entrepreneurial or marketing aspect is performed.

Thirdly, the imbalance approach upholds EM as related to entrepreneurial behaviour or marketing attitude of an enterprise. This approach tries to present EM in ways where neither marketing nor entrepreneurial attitude are not fully visible in the definitions (Kurgun et al., 2011). For example, Kurgun et al. (2011) define EM “as the exploration of ways in which entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviours can be applied to the development of marketing strategy and tactics”. Hill & Wright (2000) define EM “as a style of marketing behaviour that is driven and shaped by the owner-manager’s personality”. While the three approaches are instructive, they are in no way exhaustive. Nonetheless, they underscore that EM is unconventional and not simply about entrepreneurial and marketing aspects but rather the business as a whole.

Dimensions of EM

Secondly, there is diversity of conceptual aspects which are provided by several scholars to unpack the nature of EM. Nwankwo & Kanyangale (2020) evaluated extant literature to identify the evolution of EM and the milestones, dimensions of EM and their significance in existing models in relation to the performance and survival of businesses. Subsequently, a model was developed and tested to understand the different constitutive dimensions of EM from the entrepreneurs themselves. This study by Nwankwo & Kanyangale (2020) found that the model of EM includes nine key dimensions, namely, proactiveness, innovativeness, customer intensity, risk-taking, opportunity focus, resource leveraging, market sensing, team-work and value creation. While this study asserts that all these EM dimensions are considered as very vital elements, there is need for more research as the phenomenon of EM is underdeveloped. As EM is gaining the attention of not only marketing scholars and practitioners, but also from other fields such as entrepreneurship and psychology, it is timely to ensure that we have a complete and contemporary notion of the evolution of marketing thought and practice traceable from the pre-academic marketing thoughts all the way through to the contemporary paradigm of EM.

Conclusion

Without the phenomenon of EM, marketing scholars and entrepreneurs are working with an incomplete but also not contemporary notion of the evolution of marketing thought and practice. This article has illuminated a variety of key shifts in marketing practice and thought from the past but also possible future paradigm in the domain of marketing. This article is explicit that EM, its approaches and core elements manifest an emerging paradigm of marketing with an entrepreneurial and innovation orientation. More specifically, this emerging paradigm of EM is characterized by nontraditional and entrepreneurial way of emergent marketing in which entrepreneurs are immersed in the market, and have a thorough understanding of the problem their customers are facing to identify solutions that customers seek. In this article, the evolution of marketing thought and practice is not only accompanied by the suggestion of EM as the emerging new paradigm of marketing. It is also accompanied by clarity of three possible approaches and a variety of constitutive dimensions of EM to shape the future of marketing.

References

American Marketing Association (AMA) (2017). Definition of marketing. Retrieved from https://www.ama.org/the-definition-of-marketing-what-is-marketing/

Armstrong, G. & Kotler, P. (2015). Marketing: an introduction (12th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education Inc.

Belz, F. M. & Binder, J. K. (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent processmodel. Bus. Strategy Environ, 26, 1-17.

Blessinger, P., Reshef, S. & Sengupta, E. (2018). The shifting paradigm of higher education. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20181003100607371

Blythe, J. (2005). Essentials of marketing (3rd ed.). Harlow. Pearson.

Catalin, M.C., Andreea, P., & Adina, C. (2014). A holistic approach on internal marketing implementation. Business Management Dynamics, 3(11), 9-17.

Coax, L.A. (2015). Henry's model T efficiency (1st ed.). New York Times.

Doncic, D., Peric, N. & Prodanovic, R. (2015). Holistic marketing in the function of competitiveness of the apple producers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, economics of agriculture. Institute of Agricultural Economics, 62(2), 1-15.

Hacioglu, G., Eren, S.S., Eren, M.S. & Celikkan, H. (2012). The effect of entrepreneurial marketing on firms’ innovative performance in Turkish SMEs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58(12), 871-878.

Hemann, C. & Burbary, K. (2018). Digital marketing analytics: making sense of consumer data in a digital world, instructor supplement (2nd ed.). Que Publishing.

Hill, J. & Wright, L.T. (2000). Defining the scope of entrepreneurial marketing: a qualitative approach. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 8(1), 23-46.

Hills, G.E. & Hultman, C.M. (2011). Academic roots: the past and present of entrepreneurial marketing. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 24(1), 1-10.

Jarzabkowski, P. & Wilson, D. C. (2002). Top teams and strategy in a UK university. Journal of Management Studies, 39(3), 357-383.

Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J. & Seidl, D. (2007). Strategizing: The challenges of a practice perspective. Human Relations, 60(1), 5-27.

Jones, D.B., & Monieson, D.D. (1990). Early development of the philosophy of marketing thought. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 102-113.

Jones, D.G., & Shaw, B.E.H. (2006). A history of marketing thought, handbook of marketing, Edited by Barton Weitz & Robin Wensley.

Jones, D.G.B., & Tadajewski, M. (2016). The Routledge companion to marketing history. Oxon: Routledge.

Keelson, S.A. (2012). A quantitative study of market orientation and organizational performance of listed companies: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 5(3), 101-114.

Kotler, P. & Armstrong, G. (2018). Principles of marketing (17th ed.). Pearson Europe, Middle East & Africa.

Kotler, P. & Keller, K.L. (2016). Marketing management (14th ed.). Boston: Prentice Hall, Pearson.

Kotler, P. (1972). What consumerism means for marketers. Harvard Business Review, 50(3), 48-57.

Kotler, P.I., Keller, K.L., Goodman, M., Brady, M. & Hansen, T. (2019). Marketing management (4th European ed.). Pearson Higher Education.

Kuhn, T.S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kumar, V. (2017). Integrating theory and practice in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 81(2), 1-7.

Kurgun, H., Bagiran, D., Ozeren, E., & Maral, B. (2011). Entrepreneurial marketing-The interface between marketing and entrepreneurship: A qualitative research on boutique hotels. European Journal of Social Sciences, 26(3), 340-357.

Lauterborn, B. (1990). New marketing litany: Four Ps passé: c-words take over. Advertising Age, 61(41), 26.

Levitt, T. (1960). Marketing Myopia. Harvard Business Review, 38(4), 45-56.

Martins, N.O. (2015). Why this ‘school’ is called neoclassical economics? Classicism and neoclassicism in historical context. Working Papers de Economia (Economics Working Papers) 01, Católica Porto Business School, Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

Ndubisi, E.C & Nwankwo, C.A. (2012). Relationship marketing: Customers satisfaction-based approach. International Journal of Innovative Research in Management, 3(1), 28-40.

Ndubisi, E.C. (2016). Marketing management: Principle and practice. Enugu: Optima-Publisher.

Nwankwo, C.A., & Kanyangale, M. (2020). Deconstructing entrepreneurial marketing dimensions in small and medium-sized enterprises in Nigeria: a literature analysis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 12(3), 321-341.

Shaw, E.H. (1995). The first dialogue on macromarketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 15(1), 7-20.

Skripnik, O. (2017). Choice of the marketing concept of management of housing-and-communal services. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 90, No. 1, p. 012145). IOP Publishing.

Toghraee, M.T., Rezvani, M., Mobaraki, M.H., & Farsi, J.Y. (2018). Entrepreneurial marketing in creative art based businesses. International Journal of Management Practice, 11(4), 448-464.

Whittington, R. (2002). Practice perspectives on strategy: Unifying and developing a field Paper presented at the Academy of Management.

Yan, Y.K. & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). The concept of green marketing and green product development on consumer buying approach. Global Journal of Commerce and Management Perspective, 3(2), 33-38.

Yulisetiarini, D. (2016). The effect of relationship marketing towards customer satisfaction and customer loyalty on franchised retails in East Java. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 333.

Zyman, S. (2002). The end of advertising as we know it. Wiley.