Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

The Effect of Customer Prioritization Strategy on Customer Entitlement

Svetlana V. Davis, Williams School of Business, Bishop’s University

Abstract

It is a widely held notion that customer prioritization strategies (focusing efforts on the most valuable customers) are profitable for firms. However, such increased focus consequently results in some customers receiving comparatively disadvantaged treatment. This paper performs three experimental studies involving 516 Canadian participants in 2018 to investigate how preferential treatment resulting from customer prioritization (CP) strategies relates to customer entitlement and subsequent customer retaliatory intentions. Results show that customers with strong brand relationships feel entitled if they have received disadvantaged treatment under a customer prioritization strategy. Such feelings translate into increased demands on the firm, culminating in an increased likelihood of retaliatory actions. Moreover, feelings of entitlement are exacerbated if these customers were invited to provide feedback in the creation of the CP strategy. For managers, findings indicate that customer entitlement increases for non-prioritized customers, and customer voice positively exacerbates the link between the strength of the customer brand relationship and customer entitlement. Thus, the reaction of nonvaluable customers must be measured in the development of CP strategies while encouraging customer participation in CP development may be inadvisable.

Keywords

Customer Entitlement, Customer Prioritization Strategy, Customer-Brand Relationships, Customer Voice, Customer Retaliation Intentions.

Introduction

Customer entitlement refers to a perception that one is a special customer of the firm, expecting special treatment in retail or service environments (Boyd & Helms, 2005). However, in the business-to-consumer context little is known regarding when such entitlement may occur and the consequences thereof. Understanding these conditions are crucial in enabling marketers to design their strategies in a way that would avoid triggering an increase in customers’ entitlement. This, in turn, can reduce the costs of satisfying customer demands for better treatment, as well as alleviate complaint handling and reputation loss as a result of negative word-of-mouth and other forms of retaliatory behaviors (e.g. Grégoire et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2018) triggered by increased customer entitlement.

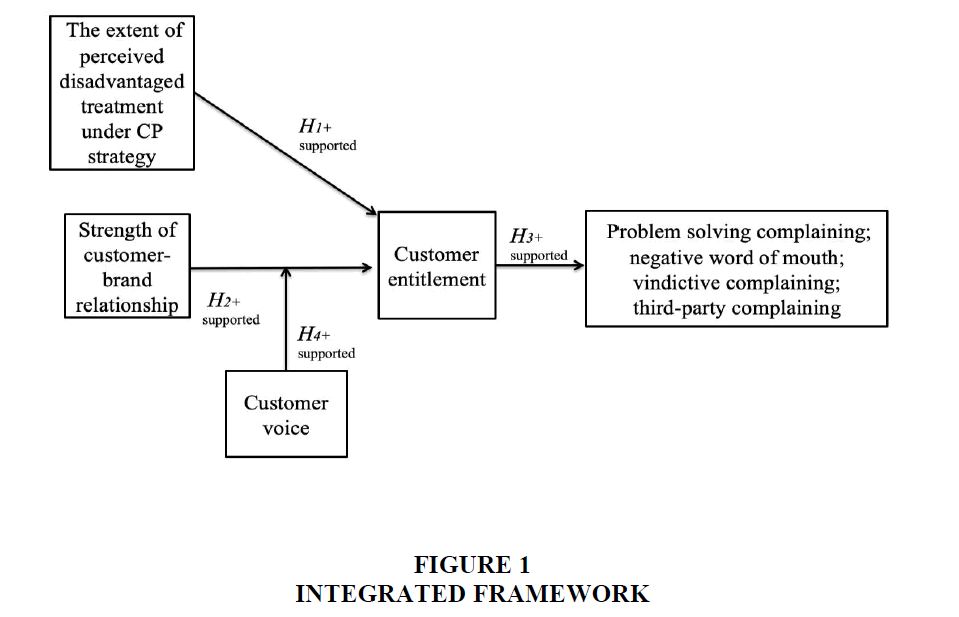

This research contributes to the literature in several important ways. First, it is shown that customer entitlement is triggered when: (a) preferential treatment arises from CP strategies; and (b) when companies foster strong customer-brand relationships. Thus, despite potential benefits for the firm (Park et al., 2013; Homburg et al., 2008), results may “backfire” as such company efforts increase customer entitlement. Second, this paper shows that the consequences of increased entitlement include customer retaliatory intentions such as an increase in problem-solving complaining, vindictive complaining, third-party complaining and negative word of mouth generation among customers. Finally, it is demonstrated herein that customer voice represents a boundary condition for the strength of customer entitlement.

Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

Disadvantaged Treatment under CP Strategies and Customer Entitlement

Customer entitlement is grounded in the construct of psychological entitlement, which has emerged from the literature on narcissism (e.g. Campbell et al., 2004; Raskin & Terry, 1988). Boyd & Helms (2005) have defined customer entitlement as

“The extent to which the buyer perceives himself or herself to be a special customer of the firm.”

This conceptualization captures customer entitlement as a stable personality trait and reflects customer propensity to have high expectations overall. Butori (2010) further expanded on this definition, arguing that customer entitlement should capture a propensity to expect special treatment and have a reference to a customer’s own treatment in comparison to that of others.

Scarce research on entitlement suggests that it can become more salient in certain retail situations and can be triggered as a reaction to company actions. For example, Kivetz & Zheng (2006) find that entitlement can be used by customers to justify indulgent consumption subsequent to hard work. Further, customers with higher loyalty status seem to also exhibit higher customer entitlement in the context of frequent flyer programs in the airline industry (Li et al., 2017). Customer entitlement has also been linked to customer perceptions of service failures (Albrecht et al., 2017; Wetzel et al., 2014) and their satisfaction with services (Zboja et al., 2016). However, it is not yet clear what factors can trigger customer entitlement in the business-to-consumer context. This paper examines two such potential triggers of customer entitlement: disadvantaged treatment under CP strategies and strong customer-brand relationships (e.g., Fernandes & Calamote, 2016; Xia & Monroe, 2017).

CP strategies are widely used strategies in which companies separate customers into groupings based on an estimated lifetime worth (Zeithaml et al., 2001) and gain efficiency by concentrating on the most profitable (high priority) customers while spending less energy and resources on low priority customers. Customers typically make their initial choice to be in a low vs. high priority customer group by purchasing higher or lower priced products or services (e.g. an 8 vs. 64 GB iPad). However, companies continue to provide new features, requiring customers to reassess these additional company actions on the level of fairness. It is common, for example, for companies to vary price and/or availability of additional features by customer groups. Such differentiated treatment under a CP strategy often leads to a process of social comparisons among the different customer groups, which could be painful for some customers (Edward et al., 2010; Xia & Kukar-Kinney, 2014).

Thus, CP strategy implementation by the company can lead to a situation in which a customer judges his/her company’s treatment as being inferior to a comparative other’s treatment and perceives a disadvantage. The customers’ baseline expectation is that the brand will treat them fairly and they will receive benefits commensurate with their expectations (Kyriakopoulos, 2011; Namin & Yavari, 2017). A violation of the fairness norm leads customers to restore fairness by demanding reparation or retaliation (Gregoire & Fisher, 2008; Sakulsinlapakorn & Zhang, 2019), increasing customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand (Figure 1).

H1: There is a positive relationship between the extent of perceived disadvantaged treatment under CP strategies and customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand.

Strength of Customer-Brand Relationship and Customer Entitlement

Brand managers focus their efforts on building strong relationships with customers such that these relationships implicate some important aspects of a customer’s self-concept (e.g. Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003; Park et al., 2010; Thomson et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2011; Sayin & Gürhan-Canli, 2015). Customers with strong brand relationships are highly profitable as they engage in difficult behaviors (as per Park et al., 2013) that are positive for the brand: a willingness to pay price premiums, purchase the brand repeatedly, and even advertise on behalf of the brand.

It seems intuitive that these customers will feel their strong relationship with the brand as indicative of a high standing in the brand’s customer hierarchy. Such feelings may exacerbate feelings of entitlement to receive better treatment. This prediction is consistent with social exchange theory: customers feel entitled to request service levels that are commensurate with their relative standing in the brand’s customer hierarchy (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

H2: There is a positive relationship between the strength of the customer-brand relationship and customers’ entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand.

Customer Entitlement and Behavioral Intentions Deemed Detrimental for the Brand

Previous research has shown that an individual’s sense of entitlement directly influences his or her corresponding behaviours (Fisk & Neville, 2011). Individuals with high levels of entitlement behave assertively, competitively, and aggressively (Fisk & Neville, 2011; Li et al., 2017), allocating themselves disproportionate levels of rewards (Campbell et al., 2004). This research similarly suggests that a higher sense of customer entitlement will be positively related to customer retaliatory intentions such as problem-solving complaining, vindictive complaining, negative word of mouth and third-party complaining.

Problem-solving complaining happens when customers approach a brand in order to find a resolution to their problem (Hibbard et al., 2001). Vindictive complaining refers to a notion that frustrated customers may contact a brand in order to inconvenience and abuse its’ employees (Hibbard et al., 2001). Negative word of mouth refers to customers’ desires to share their bad experiences with others (Wangenheim, 2005), while third-party complaining refers to a desire to make their experience with the brand known to a vast audience (Ward & Ostrom, 2006). An increase in customers’ entitlement is likely to exacerbate these retaliatory intentions.

H3: There is a positive relationship between customer entitlement and customer retaliatory intentions: problem-solving complaining, vindictive complaining, third-party complaining and spreading negative. word of mouth

Customer Voice against CP Strategy as a Moderator

Companies often ask customers for their feedback via surveys or comments on strategies they are implementing (Challagalla et al., 2009). Such feedback is designed to improve company policies and also to get customers involved in the decision making process (Goodwin & Ross, 1992; Kumar, 2010). However, what happens when customers voice their opinions against aspects of the firm’s CP strategy, but the company implements them regardless?

Customers that voice their opinions in service encounters feel as they can co-create with the brand and, consequently, feel additional perceived control and empowerment (Berry & Leighton, 2004; Karande et al., 2007). Customers’ base-line expectation is that their feedback is worth hearing, resulting in the perception that they are part of an important status group (Ofir & Simonson, 2001). Overall, the research suggests that after providing feedback customers will likely perceive a higher standing in the customer hierarchy as a special and important customer of the brand.

Given that the perception of a higher standing in customer hierarchy is an imperative part of relationship between the strength of the customer-brand relationship and customer’s entitlement, it would seem likely that the customer’s voice would play a role in this relationship. Specifically, because customers who voice their opinion against a CP strategy are likely to presume that the brand entertains their opinion, when the brand implements the strategy anyways customers will tend to be more entitled. This effect is most noticeable when customers have a stronger brand relationship since they have, a priori, perceived themselves as ranked higher with the brand. The entitlement level of customers who did not voice their opinion against a CP strategy will be less affected by the strength of the brand relationship.

H4: Customer voice will moderate the relationship between the strength of the customer-brand relationship and customer entitlement. In particular, the impact of strong customer-brand relationships on entitlement will be exacerbated for customers who voiced their opinion against aspects of the CP strategy.

Methodology-Findings And Analysis

To test the hypotheses of this research three studies were conducted. Study 1 considered triggers of customer entitlement: disadvantaged treatment under CP strategies (H1) and the strength of customer-brand relationships (H2). It also looked at consequent customer retaliatory intentions that may arise due to increased customer entitlement (H3). Study 1 was conducted in the product-based context (iPad). Study 2 tested the same hypotheses as Study 1 and was conducted in a service-based context (fitness center) for better generalizability. Study 3 looked at customer voice as a moderator of the relationship between the strength of customer-brand relationships and entitlement (H4).

Study 1

Design and Manipulations

Study 1 employed a scenario-based approach, which is regarded as a viable method in fairness research (Collie et al., 2002). It was a between-subject design with 2 levels of randomly assigned disadvantaged treatment (high/low) under a CP strategy and measured the strength of customer-brand relationships. Prior to administering scenarios, Park et al.’s (2010) measure was used to assess participants’ strength of brand relationship to their iPad. This measure was used as an independent continuous variable in our analysis in accordance with previous research (Johnson et al., 2011). 201 university students (44.9 percent male, average age 21.4 years) participated in Study 1. The students were allowed to allocate 0.5% towards their final grade increase for some of their courses.

To manipulate the extent of disadvantaged treatment under CP strategy, participants first were randomly assigned into different disadvantaged treatment groups: low vs. high (Appendix). They were further asked to imagine that some time ago they went shopping for an iPad. At that time there were three options available: an 8 GB version of iPad which was the least expensive option, a 32 GB version that was mid-range priced, and a 64 GB version which was the most expensive option. After some consideration, they ended up purchasing either the least expensive version of the iPad with 8 GB capacity (high disadvantaged treatment condition) or the most expensive version of the iPad with 64 GB capacity (low disadvantaged treatment condition).

The extent of disadvantaged treatment was manipulated by varying the additional offerings. Specifically, participants read that they received a flyer from their local Apple store offering a special deal for customers. The deal with the same benefits is only available for two customer groups: customers who purchased either the mid-range priced 32 GB iPad or the most expensive 64 GB iPad. Here, the expectation was that customers who have purchased the least expensive version of the iPad with 8 GB capacity will perceive high disadvantaged treatment since they are not eligible for the additional benefits while customers who have purchased the most expensive 64 GB iPad will perceive low disadvantaged treatment since they are eligible for the same offer as the middle priority group (Walster et al., 1973).

Measures

Customer entitlement was measured using four items on a seven point Likert-type scale (α=0.80) adapted from previous research (Butori, 2010). Sample items included: I want to receive more from Brand X than currently offered because I was treated almost the same as another customer group; I want to receive the valued customer offer for free so as to gain special attention from Brand X (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree). The manipulation of disadvantaged treatment was checked using three items (Tax et al., 1998): to what extent the offer is “reasonable”, “fair” and “I got what I deserved”.

Negative word of mouth was measured using Wangenheim’s (2005) measure (α=0.91). Vindictive complaining (α=0.91) and problem-solving complaining (α=0.94) was measured using Hibbard et al. (2001) measures. For third-party complaining (α=0.94) the measure of Ward & Ostrom (2006) was used.

Study 1 results

Manipulation checks

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to check the disadvantaged treatment manipulation. The analysis revealed a significant difference among the conditions (F(1, 199) =14.94, p< 0.001). As expected, participants in the high disadvantaged treatment (M=3.61, SD=1.54) reported a significantly lower score than those in the low disadvantaged treatment condition (M =4.41, SD=1.38; F(1, 199) = 2.13, p<0.001) on the extent to which the offer was perceived as fair (1=not fair at all to 7=very fair). This suggested manipulation was successful.

Analysis

A linear regression included two independent variables: a categorical variable for the extent of disadvantaged treatment and a continuous variable for the strength of customer-brand relationships. Customer entitlement was the dependent variable. Disadvantaged treatment under CP strategy (coded as 0-high, 1-low disadvantaged treatment group) had a significant impact on customer entitlement (β=-0.410, pb=0.017). At the same time, the strength of the customer-brand relationship had a positive influence on entitlement (β=0.106, pb=0.001). These results supported H1 and H2, highlighting the influence of the strength of customer-brand relationships and disadvantaged treatment on customer entitlement under a CP strategy.

It was also expected that the greater the customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand, the greater the intentions for problem-solving complaining, negative word of mouth, vindictive complaining and third-party complaining (H3). To test this hypothesis, four regression equations with the above customer retaliatory intentions as dependent variables were deployed. As expected, there was a positive relationship between customer entitlement and problem-solving complaining (β=0.331, t(199)=3.354, p=0.001), negative word of mouth (β=0.364, t(199)=4.462, p<0.001), vindictive complaining(β=0.310, t(199)=4.130, p<0.001), and third-party complaining (β=0.363, t(199)=3.903, p < 0.001). Hence, H3 was supported.

Discussion

Results of Study 1 supported the hypothesis. When customers perceived high (as oppose to low) disadvantaged treatment and they had strong brand relationships, customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand increased, supporting H1 and H2. H3 was also supported: as customer entitlement increased, customer retaliatory intentions increased. While this study has shown preliminary support for the predictions it has some limitations. This study has the limited context of a product-based brand, and thus lacks generalizability to other contexts. The study did not have a control group; therefore comparison to a base line was not possible. These limitations were addressed in Study 2.

Study 2

Design and Manipulations

Study 2 employed between-subject design with 3 levels of randomly assigned disadvantaged treatment (high/low/control) under a CP strategy. It measured the strength of customer-brand relationships to a fitness center that participants currently attended and used this measure as an independent continuous variable in our analysis. 187 students (49.2 percent male, average age 21.1 years) participated in Study 2. The students were allowed to allocate 0.5% towards their final grade increase for some of their courses.

As in Study 1 to manipulate the extent of disadvantaged treatment under a CP strategy, participants were first randomly assigned into different disadvantaged treatment groups: high vs. low vs. middle (Appendix). Participants read that after some consideration, they ended up purchasing either the least expensive yearly membership with exercise-only access (high disadvantaged treatment condition), the most expensive yearly membership with all-inclusive privileges (low disadvantaged treatment condition) in the fitness center or the mid-priced option (control treatment condition) in the fitness center they currently attend.

Disadvantaged treatment under CP strategy was manipulated by varying the additional offerings. Specifically, participants read that they received a flyer from the fitness center offering a special deal for members. The deal with the same benefits is only available for two customer groups: customers who purchased either the mid-priced exercise access plus one activity of your choice or the most expensive all-inclusive memberships.

Measures

After reading the scenario, participants completed a questionnaire containing the measures for customer entitlement and negative behavioral intentions as well as manipulation checks. These measures were identical to Study 1, and reliability of all measures was higher than 0.8.

Study 2 results

Manipulation checks

As in Study 1, manipulation for disadvantaged treatment was successful. Participants rated the offers they received on the extent to which the offer was fair (1=not fair to 7=very fair) in three groups: low, control and high disadvantaged treatment conditions. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference among the conditions (F(2, 185) = 11.47, p<0.001). As expected, participants in the high disadvantaged treatment condition (M=3.09, SD=1.32) reported a significantly lower score on the scale than those in the low disadvantaged treatment (M = 3.63, SD = 1.41; F(1, 125) = 2.77, p<0.05) and control conditions (M=4.26, SD=1.39; F(1, 124) = 1.09, p < .001). Also, there was a significant difference between participants in the low disadvantaged treatment (M=3.63, SD=1.41) and control conditions (M=4.26, SD=1.39; F(1, 121) =0.34, p <0.05).

Analysis

First, the relationship between disadvantaged treatment under a CP strategy, the strength of customer-brand relationship and customer entitlement was examined by performing multiple regression analysis. Our regression analysis involved a multi-categorical variable with three levels (disadvantaged treatment: 0 = high vs. 1 = low vs. 2 = control) and a continuous variable (the strength of customer-brand relationship).

Following the procedure of Hayes & Montoya (2017), disadvantaged treatment was transformed into two dummy variables: D1 and D2. Thus, the regression model included the strength of customer-brand relationship, D1, D2, the strength of customer-brand relationship x D1, and the strength of customer-brand relationship x D2 as the independent variables, and evaluations of customers’ entitlement as the dependent variable. A test of significance was conducted for the change in R² in the regression model using PROCESS model 1 with 5,000 bootstrapped samples (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). As expected, the main effects of the strength of the customer-brand relationship and disadvantaged treatment (both D1 and D2) on customers’ entitlement were significant. Consistent with our predictions in H2, participants with strong customer-brand relationships had a higher sense of customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand (β=0.119, pb=0.011). Participants in the condition of high disadvantaged treatment had a higher sense of customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand. The main effects for D1 (β=0.651, pb=0.005) and D2 (β=0.612, pb=0.008). The two-way interaction was not significant (ΔR2=0.008, F (2, 181) =0.90, p>0.05).

The mean differences for disadvantaged treatment were examined next. As expected, participants reported higher levels of entitlement in the high disadvantaged treatment condition, relative to both the low (Mhigh=5.06 vs. Mlow =4.46, t(125) =2.85, p<0.01) and control conditions (Mhigh = 5.06 vs. Mcontrol =3.81, t(124) =2.68, p<0.01). Participants also reported higher levels of entitlement in the low disadvantaged condition, relative to the control (Mlow = 4.46 vs. Mcontrol =3.81, t(121) =2.99, p<0.01). These results support H1.

The expectation was that the greater the customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand, the greater the intentions for problem-solving complaining, negative word of mouth, vindictive complaining and third-party complaining (H3). To test this hypothesis, four regression equations were conducted with the above customer retaliatory intentions as dependent variables. As expected, there was a positive relationship between perceived entitlement and problem-solving complaining (β=0.431, t(186)=3.779, p<001), negative word of mouth(β=0.391, t(186)=3.821, p<0.001), vindictive complaining(β=0.394, t(186)=3.519, p=0.001), and third-party complaining (β=0.337, t(186)=3.519, p=0.001), supporting H3.

Discussion

The purpose of Study 2 was to determine whether disadvantaged treatment under CP strategy and strong customer-brand relationships have an impact on customers’ entitlement and consequent customer retaliatory intentions. As in Study 1, results supported the above hypothesis (H1-H3) in a service-based context, thus expanding on the generalizability of this research. This study also improved upon the experimental design of Study 1 by introducing a control group.

Study 3

Design and Manipulations

Building on the first two studies, Study 3 closely followed Study 1 to test the proposed moderation hypothesis (H4) in a product brand context: Apple iPad (N=128). An experiment was conducted in a high disadvantaged treatment context with a 2 x 2 between subject design: two levels of customer voice against CP strategy implementation (voice vs. no voice), and two levels of customer-brand relationships (strong vs. weak). Further, the strength of the customer-brand relationship to Apple iPads was measured and a categorical variable was created based on the median split to represent strong (coded as 1) vs. weak (coded as 0) relationships. As an outcome variable this study measured customer entitlement (α=0.85) with the same measure as in Studies 1; reliability of all measures was higher than 0.8.

Manipulation checks

Participants read the high disadvantaged treatment scenario describing an 8GB iPad user that was not eligible to receive additional benefits as used in Study 1. As expected, participants perceived the disadvantaged treatment in the scenario to be less fair (1=not fair 7=very fair), as compared to a midpoint of 4 (M = 3.45, SD = 1.51; t(127) = - 4.17, p<0.001).

Next, customer voice was manipulated according to Sparks & McColl-Kennedy (2001). Participants in a voice-against CP strategy condition read that: “You recall that Apple previously requested your input into whether or not such customer benefits (as in this morning’s flyer) should be offered. You voiced your opinion against such offers.” At the same time participants in a no-voice condition didn’t read any additional information. Manipulation for customer voice vs. no voice condition was successful as participants correctly recalled that they previously voiced their opinion against CP strategies in a voice condition 95 % of times vs. didn’t voice their opinion against CP strategies in a no voice condition 92% of times.

Results

To test the hypothesis whether customer voice against CP strategies moderates the relationship between the strength of customer-brand relationships and customer entitlement, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted. In the first step, two categorical variables were included: strength of the customer-brand relationship (based on median split, strong vs. weak) and customer voice (voice against CP strategy vs. no voice).

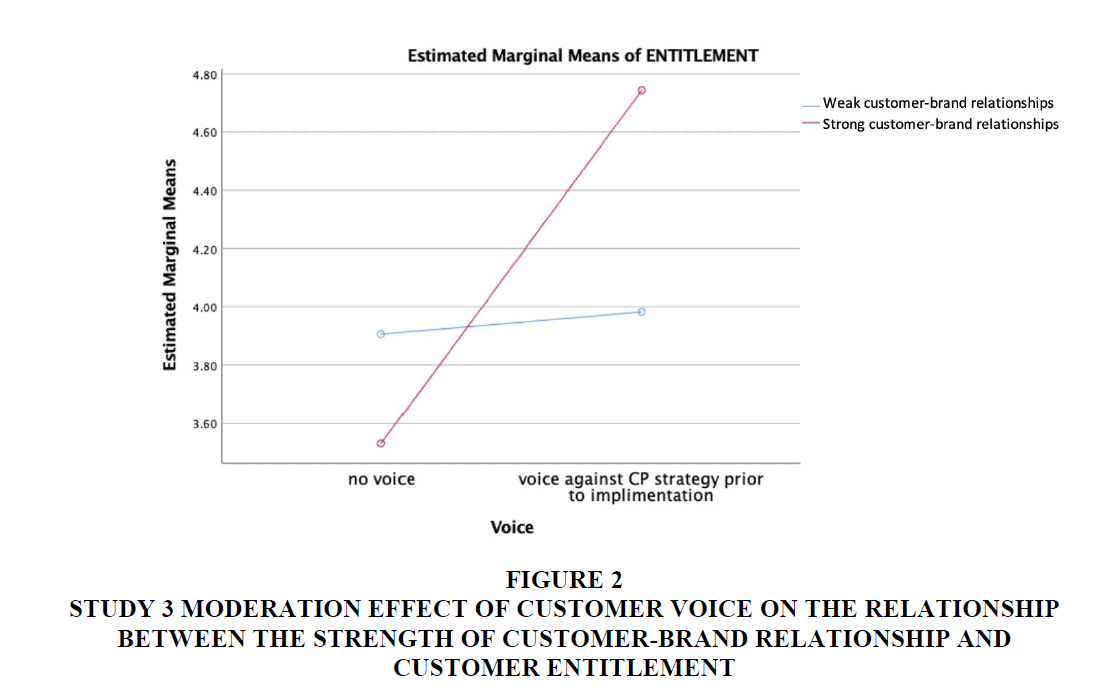

These variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand; R²=0.340, F(2, 126) = 5.74, p=0.004. Next, the interaction term between the strength of the customer-brand relationship and the customer’s voice was added to the regression model, which accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in customer entitlement; Δ R2=0.04, ΔF(1, 125) = 6.21, p=0.014, b = 1.136, t(125) = 2.49, p=0.014. Examination of the means showed an enhancing effect that when customers voiced their opinion against CP strategies, the positive effect of the strength of the customer-brand relationship on customer entitlement increased (Mstrong_BA = 4.74 vs. Mweek_BA = 3.98; t(63) =-2.62, p = 0.011). When customers did not voice their opinion against CP strategies, the effect of the strength of customer-brand relationships on customer entitlement was not significant (Mstrong_BA = 3.53 vs. Mweek_BA = 3.91; t(62) = 1.06, p>0.05) in Figure 2.

Figure 2:Study 3 Moderation Effect Of Customer Voice On The Relationship Between The Strength Of Customer-Brand Relationship And Customer Entitlement.

Results of Study 3 supported our hypothesis (H4) and demonstrated that when customers had the opportunity to voice their concerns against CP strategies, the positive effect of strong customer-brand relationships on their entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand increased. When customers had no opportunity to voice their opinion against CP strategies, the effect of the strength of customer-brand relationships on entitlement was not significant.

Discussion

Studies 1 and 2 looked at how customer entitlement arises in response to disadvantaged treatment under CP strategy and as a result of the company fostering strong customer-brand relationships in a business-to-consumer context. These studies also examined corresponding customer retaliatory intentions of increased customer entitlement. It was expected that the higher the disadvantaged treatment under a CP strategy, the higher customers’ entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand. This prediction was supported in Studies 1 and 2, using both service and product-based contexts.

This research also supported the idea that customers with strong brand relationships felt higher entitlement to receive better treatment. The idea behind this prediction was that such customers would consider their strong relationship with the brand as an indication of higher standing in customer hierarchy, which would increase their sense of entitlement. Again, this prediction was supported in both Studies 1 and 2, using service and product-based contexts.

Finally, Studies 1 and 2 looked at the retaliatory intentions of customers with a higher sense of entitlement. As expected, in both service and product-based contexts when customer entitlement increased customers increased their intentions for the following intentions: negative word of mouth, problem solving, vindictive and third-party complaining.

Study 3 looked at the boundary conditions of customer entitlement. It was expected that when customers have an opportunity to voice their opinion against CP strategies, the positive effect of strong brand relationships on customer entitlement will be enhanced. It was argued that when customers provide feedback it increases their expectations for their opinion to matter (Leary, 2001), leading to heightened status in customer hierarchy. As the firm introduces the disadvantaged treatment under a CP strategy despite customer objections, an increase in customer entitlement among customers with strong brand relationships was expected since they have a priori expectations of higher standing in the firm’s customer hierarchy. This prediction was supported in Study 3, using a product-based context.

In sum, changes in customer entitlement were triggered by the disadvantaged treatment under CP strategies and strength of customer-brand relationships. Customers’ voice (vs. no voice) against CP strategies was found to enhance (decrease) the relationship between the strength of customer-brand relationships and entitlement. An increase in customer entitlement was found to drive customer retaliatory intentions such as negative word of mouth, problem-solving, vindictive and third-party complaining. These are important findings as they highlight some limitations of using disadvantaged treatment under CP strategies and fostering strong customer-brand relationships.

Conclusion

The literature on the strength of customer-brand relationships (e.g. Park et al., 2010; Park et al., 2013; Thomson et al., 2005) focuses primarily on the benefits that strong customer-brand relationships bring to the brand. In contrast, this research contributes to our knowledge by examining the limitations of such relationships. Specifically, this paper adds to the scarce literature on customer entitlement (e.g. Kivetz & Zheng, 2006; Wetzel et al., 2014) by demonstrating that customers with strong brand relationships may feel entitled if they perceive themselves to have received disadvantaged treatment under a customer prioritization strategy.

This entitlement stems from the fact that customers consider their strong relationship with the brand as an indication of a preferred ranking in companies’ customer hierarchies. Such feelings of a higher standing with the brand lead to customer entitlement as a mechanism to demand effort from the brand which is commensurate with their standing (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). The need to acquiesce, deny, or otherwise negotiate responses to such demands is a disadvantage that finds its origins in the rollout of CP strategies.

Moreover, this research shows that a heightened sense of customer entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand leads to an increase in customer retaliatory intentions which are also detrimental for the brand: negative word of mouth, problem-solving complaining, vindictive complaining and third-party complaining. This stands in contrast to existing research which focuses only on potential outcomes which are positive for the firm, such as brand promotion, repeat purchases, and/or higher premiums (e.g., Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003; Park et al., 2013). Thus, understanding how customer intentions change, not only to demand more from the firm but to engage in retaliatory actions, must be considered by managers upon the initiation of CP strategies to avoid the need to invest additional resources into customer conflict resolutions.

Furthermore, this research shows that feelings of entitlement are exacerbated (decreased) if customers with strong brand relationships previously voiced (did not voice) their opinion on the CP strategy at its inception. Taken together, results imply that managers need to measure the costs associated with increased entitlement resulting from CP strategies before embarking on such programs. Additionally, perhaps surprisingly, managers may need to refrain from asking for feedback on CP development from customers with strong brand relationships (unless managers are willing to acquiesce to demands) in order to decrease feelings of entitlement.

CP strategies separate customers into different priority groupings based on the amount of worth that each customer represents for the company (e.g. Homburg et al., 2008; Zeithaml et al., 2001). This research suggests that such a separation would also benefit from consideration of customer brand relationships. We show that customers with strong brand relationships are much more sensitive to disadvantaged treatment and have stronger entitlement to receive better treatment from the brand. This is an important finding and must be considered by managers when designing CP strategies as to avoid consequent retaliatory intentions that may arise due to a heightened sense of customer entitlement.

Limitiations and Scope Of Future Research

This research has its limitations. Due to the use of student participants, it is not possible to know whether the effects described in this paper will hold in an uncontrolled environment. Thus, a field experiment and/or an experiment with different participant groups would improve this paper’s generalizability.

Future research might investigate other contexts in which customer entitlement may arise as a result of managerial actions. In addition, exploration of either the type of feedback requested of customers with regards to CP development, or the manner in which such feedback is requested, may provide insight into how to mitigate resulting costly behaviors.

Appendix

Scenario Study 1. Product Context: Ipad

<High disadvantaged treatment> vs. {low disadvantaged treatment}

Imagine that some time ago you went shopping for an iPad. At that time there were three options available to you: an 8 GB version of iPad which was the least expensive option, a 32 GB version that was mid-range priced, and a 64 GB version which was the most expensive option. After some consideration, you ended up purchasing <the least expensive version of iPad with 8 GB capacity.> {the most expensive version of iPad with 64 GB capacity.}

In your mail this morning was a flyer from your local Apple store offering a special deal for iPad customers. The flyer indicates that “For a small, one-time additional fee, valued iPad owners are able to receive their choice of one of the following benefits:” The flyer continues to list several possible choices, including options for design, performance, and service-related enhancements. Apple further indicates that the offer is only available for owners of either the mid-range priced 32 GB iPad or the most expensive 64 GB iPad. The offer is identical for these users and has the same minimal fee. Owners of the 8 GB model are not eligible for this offer and such enhancements are not available in any other fashion from the company.

Scenario Study 2. Service Brand: Fitness Center

<High disadvantaged treatment> vs. {low disadvantaged treatment} vs. [control]

Imagine that some time ago you went to a fitness center and bought a one-year membership. At that time there were three options available to you for a yearly membership: exercise-only access for the lowest price; exercise access plus one activity of your choice for a mid-range price; and finally an all-inclusive option which was the most expensive option. After some consideration, you ended up purchasing <the least expensive yearly membership with exercise-only access.> {the most expensive yearly membership with all-inclusive privileges.} [The mid-priced exercise access plus one activity of your choice.]

In your mail this morning was a flyer from your local fitness center offering a special deal for members. The flyer indicates that “For a small, one-time additional fee, valued users of this center are able to receive their choice of one of the following benefits”. The flyer continues to list several possible choices, including options for personal training sessions, access to newer and more plentiful equipment, and other service-related enhancements. The flyer further indicates that the offer is only available for two customer groups: customers who purchased either the mid-priced “exercise access plus one activity of your choice” or the most expensive “all-inclusive” memberships. This same offer is available for both of these customer groups for the same (minimal) fee; purchasers of the exercise-only membership are not eligible for this offer and are not eligible to receive these benefits outside of this offer.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, 430-2016-00782. The author wishes to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

References

- Albrecht, A.K., Walsh, G., & Beatty, S.E. (2017) Perceptions of Group Versus Individual Service Failures and Their Effects on Customer Outcomes: The Role of Attributions and Customer Entitlement.Journal of Service Research,20(2), 188-203.https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670516675416

- Berry, L.L., & J.A. Leighton (2004). Restoring Customer Confidence. Marketing Health Services, 24(Spring), 14-19.

- Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2003).Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers? relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

- Boyd, H.C., & Helms, J.E. (2005). Consumer entitlement theory and measurement. Psychology & Marketing, 22(3), 271. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20058

- Butori, R. (2010). Proposition for an improved version of the consumer entitlement inventory. Psychology & Marketing, 27(3), 285-297. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20327

- Cai, R. Lu, L., & Gursoy, D. (2018). Effect of disruptive customer behaviors on others' overall service experience: An appraisal theory perspective.Tourism Management, 69,330-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.013

- Campbell, W.K., Bonacci, A.M., Shelton, J., Exline, J.J., & Bushman, B.J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29-45. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjpa20

- Challagalla, G., Venkatesh, R. & Kohli, A. (2009). Proactive Postsales Service: When and Why Does It Pay Off? Journal of Marketing, 73(March), 70-87.

- Collie, T., Bradley, G. & Sparks, B. (2002). Fair process revisited: Differential effects of interactional and procedural justice in the presence of social comparison information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(6), 545-555. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00501-2.

- Cropanzano, R. & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874-900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Edward, M., George, P. & Sarkar, S.(2010). The Impact of Switching Costs Upon the Service Quality-Perceived Value-Customer Satisfaction-Service Loyalty Chain: A Study in the Context of Cellular Services in India.? Services Marketing Quarterly,31(2),151-173,DOI:10.1080/15332961003604329

- Fernandes, T., & Calamote, A. (2016). Unfairness in consumer services: Outcomes of differential treatment of new and existing clients. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 36-44.

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.08.008

- Fisk, G.M., & Neville, L.B. (2011). Effects of customer entitlement on service workers' physical and psychological well-being: A study of waitstaff employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023802

- Goodwin, C. & Ross, I. (1992). Consumer responses to service failures: Influence of procedural and interactional fairness perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 25(2), 149-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(92)90014-3

- Gregoire Y., & Fisher, R. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 247-261. DOI 10.1007/s11747-007-0054-0

- Grégoire, Y., Tripp, T.M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance.Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 18-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.18

- Hayes, A.F., & Montoya, A.K. (2017). A tutorial on testing, visualizing, and probing an interaction involving a multicategorical variable in linear regression analysis. Communication Methods and Measures, 11, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1271116

- Hibbard, J.D., Kumar, N., & Stern, L.W. (2001). Examining the impact of destructive acts in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 45-62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1558570

- Homburg, C., Droll, M., & Totzek, D. (2008).Customer prioritization: Does it pay off, and how should it be implemented? Journal of Marketing, 72(5), 110-130. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.72.5.110

- Johnson, A.R., Matear, M., & Thomson, M. (2011). A coal in the heart: Self-relevance as a post-exit predictor of consumer anti-brand actions. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(1), 108-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/657924

- Karande, K., Magnini, V.P., & Tam, L. (2007). Recovery voice and satisfaction after service failure: An experimental investigation of mediating and moderating factors.Journal of Service Research: JSR,10(2), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507309607

- Kivetz, R., & Zheng, Y. (2006). Determinants of justification and self-control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 135(4), 572-587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.572

- Kumar, V. (2010). Customer Relationship Management. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing (eds J. Sheth and N. Malhotra). doi: 10.1002/9781444316568.wiem01015

- Kyriakopoulos, G. (2011). The role of quality management for effective implementation of customer satisfaction, customer consultation and self-assessment, within service quality schemes: A review. African Journal of Business Management, 5(12), 4901-4915. DOI: 10.5897/AJBM10.1584.

- Leary, M.R. (2001). Toward a Conceptualization of Interpersonal Rejection. InInterpersonal Rejection, ed. Mark R. Leary, New York: Oxford University Press, 3-20.

- Li, X., Ma, B. & Zhou, C.(2017).Effects of customer loyalty on customer entitlement and voiced complaints.The Service Industries Journal,37:13-14,858-874,DOI:10.1080/02642069.2017.1360290

- Namin, A.T. & Yavari, E. (2017). Service desk management tasks for customer satisfaction & service quality. International Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(4), 780-798.

- Ofir, C., & Simonson, I. (2001). In Search of Negative Customer Feedback: The Effect of Expecting to Evaluate on Satisfaction Evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(August), 170-82.

- Park, C.W., Eisingerich, A.B., & Park, J.W. (2013).Attachment?aversion (AA) model of customer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.01.002

- Park, C.W., Macinnis, D.J., Eisingerich, J.P., & Iacobucci. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.6.1

- Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(5), 890. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

- Sakulsinlapakorn & Zhang (2019). When Love-Becomes-Hate Effect Happens: An Empirical Study of the Impact of Brand Failure Severity Upon Consumers Negative Responses. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 23(1), 1-22.

- Sayin, E. & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2015). Feeling Attached to Symbolic Brands within the Context of Brand Transgressions. InD.J. Macinnis&C. Whan Park(ed.), Brand Meaning Management, 233-256,Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Sparks, B.A., & McColl-Kennedy, J.R. (2001). Justice strategy options for increased customer satisfaction in a services recovery setting.Journal of Business Research, 54(3), 209-218.

- Tax, S., Brown, S.W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200205

- Thomson, M., MacInnis, D.J., & Park. C.W. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of customers? attachments to brands. Journal of Customer Psychology, 15(1), 77-91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1501_10

- Walster, E., Berscheid, E., & Walster, G.W. (1973). New directions in role of protest framing in customer-created complaint web sites.

- Wangenheim, F.V. (2005). Postswitching negative word-of-mouth. Journal of Service Research, 8(1), 67-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670505276684

- Ward, J.C., & Ostrom, A.L. (2006). Complaining to the masses: The role of protest framing in customer-created complaint web sites. Journal of Consumer Research, 33, 220-230. https://doi.org/10.1086/506303

- Wetzel, H.A., Hammerschmidt, M., & Zablah, A.R. (2014). Gratitude versus entitlement: A dual process model of the profitability implications of customer prioritization. Journal of Marketing, 78(2), 1-19.

- Xia, L., & Kukar-Kinney (2014). For our valued customers only: examining consumer responses to preferential treatment practices. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2368-2375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.02.002.

- Xia, L., & Monroe, K.B. (2017).It?s not all about the money: The role of identity in perceived fairness of targeted promotions. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26(3), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2016-1196

- Zboja, J.J.,Laird, M.D., &Bouchet, A.(2016).The moderating role of consumer entitlement on the relationship of value with customer satisfaction.Journal of Consumer Behaviour,15,216-224. doi:10.1002/cb.1534.

- Zeithaml, V.A., Rust, R.T. & Lemon, K.N. (2001).The Customer Pyramid: Creating and Serving Profitable Customers. California Management Review, 43(4), 118-142. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166104