Short communication: 2021 Vol: 22 Issue: 1

The Economics of Sexual Harassment

Hussin J. Hejase, Senior Researcher, Beirut

Abstract

The ailing problem of sexual harassment is a global issue that has been exposed, studied, analyzed and mitigated to a certain degree. However, has never been under control. The negative consequences of the impact of sexual harassment on the economics of institutions have been monetized to measure the financial damage. In fact, workplace sexual harassment incidents imposed a number of economic costs on the institutions including costs of absenteeism, presenteeism (working more hours at work), staff turnover, and manager time. In addition to the various costs incurred including costs of health system, jurisdictional agency investigations, individual legal fees, government justice system costs, and deadweight (market inefficiency) losses. Therefore, the economic costs impact is remarkable though not much exposed statistically in the reported studies. The aim of the current essay is to shed light on the secondary literature content pertaining to the subject in order to create awareness based on facts and figures which are needed for better decision making.

Keywords

Sexual Harassment, Economy, Costs, Management.

Introduction

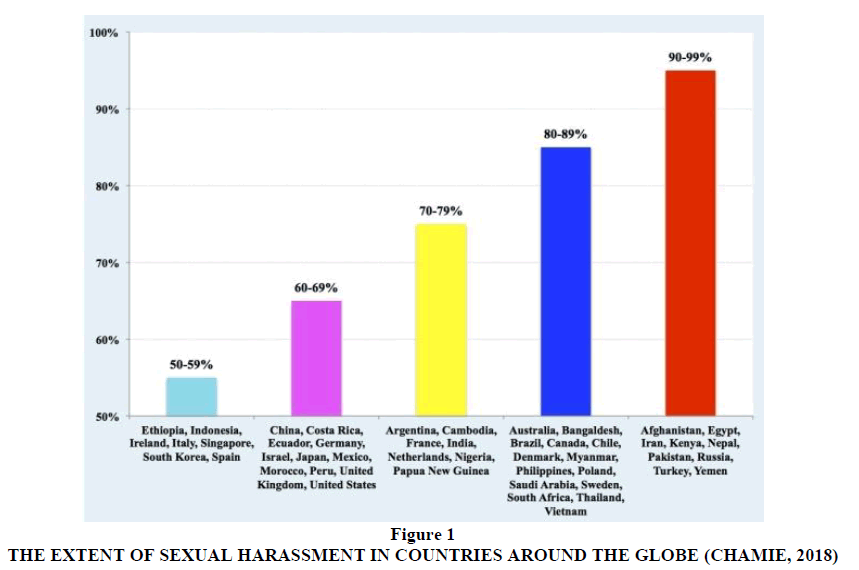

Most of the world’s women have experienced sexual harassment (SH). Hejase (2015), define sexual harassment as “unwelcomed or unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and any form of verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature that interferes with one’s employment or work performance or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment”. According to Chamie (2018), “Based on available country surveys, it is estimated that no less than 75 percent of the world’s 2.7 billion women aged 18 years and older, or at least 2 billion women, have been sexually harassed”. Furthermore, the reported estimated percentages of women who have experienced sexual harassment varies considerably across countries from lows of around 50 percent to highs above 90 percent (UN Women, 2020; Deloitte Access Economics, 2019; Chamie, 2018, Senthilingam & Mankarious, 2017). Chamie (2018) presents Figure 1 to show the extent of sexual harassment in countries around the globe.

Even though the problem of sexual harassment is usually attributed to women victims, men are also victims. Yahnke (2018) presents several supporting studies including: “Washington Post, 2010, reported that 10% of men have been victims of sexual harassment at work; a 2014 study in Canada: women are twice as likely as men to report unwanted sexual contact in the office (20% and 9%, respectively); Quinnipiac University study: 20% of men reported being sexually harassed. While statistics from Atlantic Training (17 to 20%) and a 2017 YouGov poll (15%); and a Canadian online found that more than one-third of women and about one in ten men had been victims of workplace sexual harassment”. Furthermore, Benya et al. (2018) report in their book those women are more likely to be sexually harassed than men and to experience sexual harassment at higher frequencies. In fact, “in terms of Federal workers, it found more women (44%) than men (19%); graduate students while in graduate school. Female students were 1.64 times more likely to have experienced sexually harassing behavior from faculty or staff (38%) compared with male students (23%); and as for Active Duty Military Women and Men Experiencing Sexually Harassing Behaviors, the rates were an average 44% versus 17.5%.”

Therefore, all countries are concerned about the negative consequences of sexual harassment on both dimensions the humane and the monetary. In particular here, we are concerned about the monetary part. According to Deloitte Access Economics (2019), and based on a 2.5 million cases, “the economic costs of sexual harassment reached AUD 2.6 billion in lost productivity, or AUD 1,053 [~800 USD] on average per victim; in addition to AUD 0.9 billion in other costs, or AUD 375 [~285 USD]on average per victim”. Therefore, if we apply these numbers (provided that the reported figures are governed by strict in-situ conditions) to the total victims worldwide of 2 billion women (Chamie, 2018) and assuming a conservative rate of 600 million men (based on different reports herein), then the economic costs rise as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Estimation of Global Economic Costs Due to Sexual Harassment for the Year 2018 |

| Global losses of productivity: |

| (800)(2,000,000,000) = 16x1011 USD for sexually harassed women |

| (800)(600,000,000) = 4.8x1011 USD for sexually harassed men |

| Global losses of sexual harassment consequences: |

| (285)(2,000,000,000) = 5.7x1011 USD for sexually harassed women |

| (285)(600,000,000) = 1.71x1011 USD for sexually harassed men |

| Total: |

| SH-Women: 21.7x1011 USD |

| SH-Men : 6.51x1011 USD |

| Overall SH economic Costs: 28.21x1011 USD or 2.821 billion USD |

The above costs are hypothetical, though representative of the economic costs of sexual harassment. The aforementioned may not include out-of-the-court settlements carried out between organizations and their victims for the sake of privacy and conservation of the branding. The point to make here, is that there is so much waste of resources due to deviant behavior in all cultures around the nations. In fact, Chamie (2018) expressed his concern asserting that, “In many societies there is a general tolerance of sexual harassment, being viewed as part and parcel of daily life, with many shrugging it off just as another unpleasant fact of a woman’s life, especially at the work place. Also, some women have come to recognize the pervasiveness of quid pro quo sexual harassment and sadly concluded that in order get what you want; you need to give them what they want”.

Outcomes and Progress of Solutions

The economic costs of workplace sexual harassment are shared by individuals, their employers, government, and society. The Deloitte Access Economics (2019) found that “Approximately two thirds of lost productivity (70%) is borne by employers, with government (23%) losing tax revenue, and individuals (7%) losing income” (p. 6).

The recurring problem of sexual harassment and the immense spread across the globe, especially against women, have pushed the world to see not only how society has failed to protect women, but also where governments have failed to protect their citizens. Nevertheless, according to Stauffer (2020), “The 2019 International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention on Violence and Harassment at Work—which 439 out of 476 governments, employers, and workers from around the world voted to adopt in June at the United Nations in Geneva—sets out key measures to tackle the scourge of harassment at work. These include the adoption of national laws prohibiting workplace violence and taking preventive measures, as well as requiring employers to have workplace policies on violence. The treaty also obligates governments to provide access to remedies through complaint mechanisms, victim services, and to provide measures to protect victims and whistleblowers from retaliation”.

References

- Benya, F.F., Widnall, S.E., & Johnson, P.A. (Eds.) (2018). Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Retrieved December 22, 2020, fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519455/

- Chamie, & Joseph. (2018). Sexual Harassment: At Least 2 Billion Women. Inter Press Service News Agency. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from http://www.ipsnews.net/2018/02/sexual-harassment-least-2-billion-women/

- Deloitte Access Economics. (2019). The economic costs of sexual harassment in the workplace: Final report, March 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/ Economics /deloitte-au-economic-costs-sexual-harassment-workplace-240320.pdf

- Hejase, H.J. (2015). Sexual harassment in the workplace: An exploratory study from Lebanon. Journal of Management Research, 7(1), 107-121.

- Senthilingam, M., & Mankarious, S.G. (2017). Sexual Harassment: How it stands around the globe. CNN Health, 11(29), 17.

- Stauffer, & Brian. (2020). Two Years After #MeToo Erupts, A New Treaty Anchors Workplace Shifts Array. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/global-1

- Women, U.N. (2019). Facts and figures. Retrieved from arabstates. unwomen. org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures.

- Yahnke, & Katie. (2018). Sexual Harassment Statistics: The Numbers Behind the Problem. I-Sight. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://i-sight.com/resources/sexual-harassment-statistics-the-numbers-behind-the-problem/#:~: text =A% 20survey%20by%20Quinnipiac%20University,poll%20(15%20per%20cent).