Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 4

The Dissolution of Political Parties in Indonesia: Lessons Learned from the European Court of Human Rights

Pan Mohamad Faiz, Constitutional Court of Indonesia

Abstract

This article aims to examine several important decisions related to the dissolution of political parties decided by the international human rights courts. It aims to conclude that there are general guidelines on political party dissolution established by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and uses sources obtained from relevant case studies to support it. Not only does the research highlight that the ECtHR provides requirements that must be fulfilled by the government to justify dissolution, it also dictates the procedural requirements for the restriction of political parties. These guidelines are necessary in a democratic society, regardless of its limited ‘margin of appreciation’. Although Indonesia is not a state party to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, the interpretation and legal considerations made by ECtHR could be applied by the Constitutional Court in deciding the outcome of political party dissolution cases in Indonesia. Thus, ensuring that the Constitutional Court’s future jurisprudence complies with the international standards of human rights.

Keywords

Constitutional Court, European Court of Human Rights, Freedom of Association, Political Party Dissolution.

Introduction

The 2002 constitutional reform created many fundamental changes in the Indonesian constitutional structure. To strengthen the checks and balances system among governmental powers, the Indonesian Constitutional Court was established in 2003 as a separate judicial institution from the Supreme Court (Butt, 2015). The Constitutional Court was granted the power to dissolve political parties based on the government’s request. In Indonesian history, the government has dissolved several political parties, such as the Masyumi Party, the Indonesian Socialist Party/PSI, and the Indonesian Communist Party/PKI (Madinier, 2015). Ironically, for these cases the government made a unilateral decision without referring to the judicial process (Asshiddiqie, 2005; Safa’at, 2011). As such, granting authority to dissolve political parties to the Constitutional Court is a limitation of the government’s power. It establishes a judicial forum that offers an opportunity for political parties to defend their rights, as well as to challenge the government’s justifications for dissolving political parties. This forum aims to provide a fair, transparent, and accountable judicial process.

Although regulated in Indonesian Political Parties Law, the Constitutional Court is yet to receive or handle a case on the dissolution of political parties to date. Therefore, it has become relevant to learn of the experiences and general principles established by other countries in dissolving political parties through the court should a similar case arise in Indonesia. The reason for its importance is that Indonesia is a state party to the ICCPR. Consequently, Indonesia is committed to respecting international human rights norms and following the existing jurisprudence of human rights bodies.

Research Methodology

The legal references referred to in this research are drawn from various international and regional conventions, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the United Nations Convention against Corruption, and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR). In addition, it also uses relevant academic references from books, journal articles, and reports to strengthen its arguments. As a comparative study, the analysis in this research refers to important decisions in

“ yazar arata Aksoy and the People’s Labour Party (HEP) v. Turkey case; United Communist Party of Turkey and Others v. Turkey case; Refah Partisi (The Welfare Party) and Others v. Turkey case; Socialist Party of Turkey (STP) and others v Turkey case; Herri Batasuna and Batasuna v. Spain case; and Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) v. Germany case”.

Result And Discussion

There is only one article in the Indonesian Constitution relating to the dissolution of political parties. Article 24C does not detail the process that should be used by the Court to dissolve political parties, only offering an explanation of the initial and final stage of the decision process. Nevertheless, Law 24 of 2003 states that the government is the only entity that can file an application for the dissolution of political parties before the Constitutional Court. The application must describe clearly that which is outwardly against the law, be it the ideology, the principles, the objectives, the program or the activities of the political party concerned. However, if the application does not meet the requirements, it shall be rejected and deemed as inadmissible.

The legal standards when assessing the compatibility of the ideology, the principles, the objects, the program or the activities of a political party with the Constitution are a pivotal matter. This issue is explicitly mentioned in Law Number 2 of 2008 on Political Parties. Under Article 41, political parties can be dissolved because of either its own decision, merging with other political parties or the Constitutional Court decision. The latter should be based on evidence that the political parties are proven to have violated the prohibitions for political parties regulated in the Political Parties Law. There are five categories of prohibitions.

First, political parties are prohibited from using the same names, symbols or images:

1. National flag and state emblem of the Republic of Indonesia;

2. Symbol of state institution or government;

3. Name, flags, state emblem of other states or international organizations;

4. Name, flag, symbol of separatist movement organizations or banned organizations;

5. Name or image of a person;

6. Or having a partial or full similarity with the name, symbol or image of other political parties. If political parties that already have a legal entity status violate these prohibitions, the political parties shall be subject to administrative sanctions in the form of suspension of the board members by the district court.

Second, political parties are prohibited from conducting activities that act in contrast to the Indonesian Constitution and the national laws. They are also prohibited from conducting activities that endanger the integrity and national security of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. Violations of these prohibitions shall be subject to administrative sanctions in the form of temporary suspension of the political parties by the district court for a maximum of one year. Furthermore, if political parties that have been suspended still violate those prohibitions, the Constitutional Court can dissolve them.

Third, with regard to financial regulations, political parties are prohibited from:

1. Receiving or giving donations to a foreign party in any form that is contrary to the laws and regulations;

2. Receiving donations in the form of money, goods or services from any party without a clear identity;

3. Receiving donations from individuals and/or companies/business entities exceeding the limits set out in the laws and regulations;

4. Requesting or receiving funds from state-owned enterprises, regional-owned enterprises, and village-owned enterprises or other equivalent institutes;

5. Using factions in the People’s Consultative Assembly, the House of Representative, the Provincial House of Representative and the Regency/Municipal House of Representative as a source of funding for political parties. If political parties violate these prohibitions, they cannot be dissolved, however their board members can be sentenced to a maximum of one to two years of imprisonment and a fine worth twice the amount of the funds received.

Fourth, political parties are also prohibited from establishing business entities and/or owning shares of business entities. Violations of this prohibition shall be subject to administrative sanctions in the form of suspension of the boards of political parties by the district court. Moreover, its assets and shares will be seized by the state. Finally, political parties are prohibited from embracing, developing, and disseminating the teachings of communism or Marxism-Leninism. If political parties violate this prohibition, they will not be suspended. Instead, sanctions will be imposed resulting in their dissolution. This prohibition was created based on historical and political grounds related to the event of the coup d’état attempt that involved the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) in 1965 (Roosa, 2006). Such restrictions have become a heated debate in many countries for a long time, especially those that adhere to the principle of militant democracy, whether it is contrary to the freedom of association or not (Loewenstein, 1937).

Based on the applicable laws and regulations explained above, the dissolution of political party is an ‘ultima ratio’ in the Indonesian legal system. Political parties in Indonesia can be dissolved if their activities are contrary to the Constitution and national laws as well as an endangerment to the integrity and national security of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. However, they shall be suspended prior to their dissolution. The only ground where political parties can be directly dissolved without any suspension is if they embrace, develop and disseminate the teachings of Communism or Marxism-Leninism. Unfortunately, there is no clear definition on communism, Marxism or Leninism in the Constitution or in any relevant law in Indonesia.

Due to not having previously received a case on the dissolution of political parties, the Court is largely inexperienced, requiring it to learn from the experience and ratio decidendi made by other courts in different regions. This can be done by familiarizing itself with the various international standards and frameworks concerning political parties.

International Standards on Political Parties

This section details global and regional standards on political parties. On a global level, several international conventions can be taken into account by the Constitutional Court in dealing with political parties:

1. Article 19 (the right to freedom of opinion and expression) and Article 20 (the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

2. Article 2 (the right to free from discrimination), Article 14 (the limitations on rights and freedoms), Article 19 (the right to freedom of opinion and expression) and Article 22 (the right to freedom of association) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) (ICCPR).

3. Article 3, Article 4, and Article 7 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

4. Article 2 and Article 4 of the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

5. Article 7(3) of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCC).

Furthermore, on a regional level, the Council of Europe has enacted several conventions, decisions, and recommendations regarding political parties:

1. Article 10 (freedom of expression), Article 11 (freedom of assembly and association) and Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR).

2. Protocol 12, Article 1 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

3. Article 4 and Article 7 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

4. Article 3 of the Convention on the Participation of Foreigners in Public Life at the Local Level.

5. Recommendation and Resolutions adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, in particular, Resolution 1308 (2002) Restrictions on political parties in the Council of Europe member states, Resolution 1344 (2003) Threat posed to democracy by extremist parties and movements in Europe, Resolution 1546 (2007) The code of good practice for political parties.

6. Recommendations and Resolutions adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, in particular, Recommendation (2003) on common rules against corruption in the funding of political parties and electoral campaigns.

Other critical international instruments concerning political parties can also be found in Article 12, Article 21 and Article 23 of the Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union as well as Article 5.4, Article 5.9, Article 7.5, Article 7.6, Article 9.1, Article 9.2, Article 9.3 and Article 9.4 of the Document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). Nevertheless, the Copenhagen Document does not have the force of binding law. However, the nature of these political commitments makes them persuasive upon signatory states (Venice Commission CDL-AD, 2010).

Additionally, the Venice Commission, an advisory body of the Council of Europe, has also established essential principles on prohibition and dissolution of political parties and analogous measures. The principles were created based on the provisions of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and the values of the European legal heritage (Venice Commission CDL-INF, 2000), as follows:

1. The prohibition or enforced dissolution of political parties may only be justified in the case of parties which advocate the use of violence or use violence as a political means to overthrow the democratic constitutional order, thereby undermining the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. The fact alone that a party advocates a peaceful change of the Constitution should not be sufficient for its prohibition or dissolution.

2. A political party as a whole cannot be held responsible for the individual behaviour of its members not authorised by the party within the framework of political/public and party activities.

3. The prohibition or dissolution of political parties is a particularly far-reaching measure and should be used with the utmost restraint. Before asking the judicial body to prohibit or dissolve a party, governments or other state organs should assess, having knowledge of the situation of the country concerned, whether the party really represents a danger to the free and democratic political order or to the rights of individuals. In addition, whether other, less radical measures can be taken.

4. Legal measures directed at the prohibition or legally enforced dissolution of political parties shall be a consequence of judicial findings and shall be deemed as being of an exceptional nature and governed by the principle of proportionality. Any such measure must be based on sufficient evidence of the party itself and not only of individual members’ pursuit of political objectives through unconstitutional means.

These standards and guidelines are fundamental as a reference for the national court in dealing with the dissolution of political party cases in a democratic society. International human rights instruments contained in international conventions, such as ICCPR, CEDAW, CERD, and UNCC, are binding by virtue of their ratification by Indonesia. However, Indonesia is not bound by several regional conventions, decisions, and recommendations given by the Council of Europe or the Venice Commission. Nevertheless, the Indonesian Constitutional Court often uses international and regional human rights instruments in examining various legal and constitutional issues. Judge Palguna of the Indonesian Constitutional Court explained that citing international law has helped the Indonesian Constitutional Court in making its decisions (Palguna, 2017).

“Citing international law in a decision has helped the Court reach a comprehensive ‘ratio decidendi’ to a particular case before arriving at its final ruling. In other words, the citation has helped the Court build a constitutional interpretation in a concrete case.”

Therefore, discussing regional human rights instruments related to the dissolution of political parties remains relevant to the Indonesian Constitutional Court, including the decisions made by international human rights courts. The next section will investigate three selected jurisdictions in international human rights law concerning freedom of association as related to political parties, namely:

1. The UN Human Rights Committee;

2. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR);

3. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

The UN Human Rights Committee

The main international instrument that should be considered when resolving cases on the dissolution of political parties is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights/ICCPR (1966). Article 22 of the ICCPR recognises the right to freedom of association, not only for an individual but also for the collective right of an existing association (Nowak, 2005). This right cannot be separated from Article 19 of the ICCPR which guarantees the right to hold opinions and the right to freedom of expression. Regarding the right to freedom of association, Article 22 paragraph (2) of the ICCPR regulates:

“No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those which are prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

Although the Human Rights Committee has decided on eight cases based on that provision, unfortunately, it has not provided a detailed insight concerning the issue of freedom of association with reference to the dissolution of political parties or freedom of association in general (Tyulkina, 2014). However, the Human Rights Committee provides general requirements and a proportionality test for deciding the cases.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR)

The right to freedom of association is also guaranteed in Article 16 of the American Convention of Human Rights, a convention modeled on both the UN human rights instruments and the European Convention (Pasqualucci, 1995). The article stipulates that everyone has the right to associate freely for ideological, religious, political, economic, labour, social, cultural, sports, or other purposes. This convention provides similar grounds like the ICCPR regarding the restrictions on the exercise of the right to freedom of association. It shall be subject only to such restrictions as may be ‘necessary in a democratic society, in the interest of national security, public safety or public order, or to protect public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others’.

The IACHR does not have any cases for interpreting and applying Article 16 of the Convention in relation to the dissolution of political parties. Some cases that make mention of political parties’ fates that have been decided by the IACHR are “Yatama v Nicaragua and Castaneda Gutman v Mexico” (Pasqualucci, 1995). However, the former case is related to the prohibition of Yatama as a public association to participate in the regional elections. This was because it had not obtained legal status as a political party. The latter case is related to a person named Castaned Gutman who was refused by the electoral commission to be registered as an independent candidate for the presidential election in 2016. This was a result of the electoral law regulating that only national political parties can propose and register presidential candidates. Thus, the jurisprudence of the IACHR concerning the dissolution of political parties is also not extensive (Tyulkina, 2014).

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)

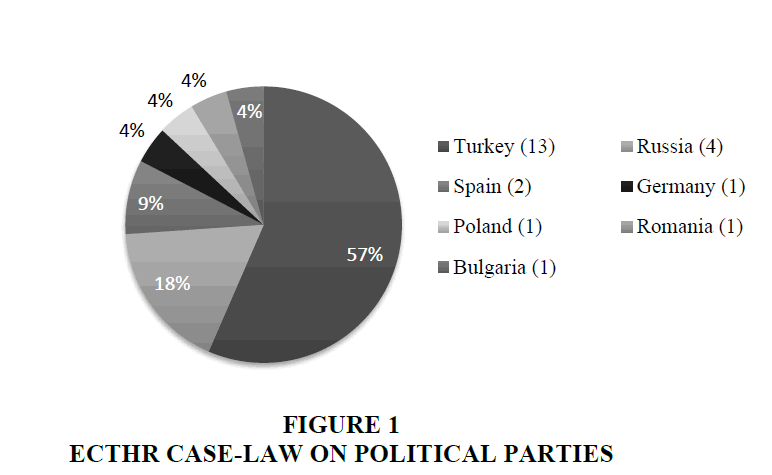

Given that the ECtHR has more jurisprudence regarding the dissolution of political parties compared to the other jurisdictions, relevant case-law that has been decided by the ECtHR will be analysed in more detail. At the time of writing, the ECtHR has already decided 23 cases concerning the existence of political parties since 1957. These consist of 13 cases from Turkey, 4 cases from Russia, 2 cases from Spain, 1 case from Germany, 1 case from Poland, 1 case from Romania, and 1 case from Bulgaria. The Figure 1 for these cases can be found below:

Based on this data, most of the cases were submitted by political parties from Turkey, a country known as ‘a graveyard of political parties’ (Moral and Tokdemir, 2016). Indeed, 27 political parties have been banned in Turkey. The two significant grounds for these party closures were political Islamism and violation of secularism, as well as the Kurdish left-wing and the violation of territorial integrity/national unity (Tumay, 2016; Celep, 2014; Esen, 2012; Kogacioglu, 2003). Interestingly, the ECtHR only upheld one case concerning the dissolution of Turkish political parties, i.e., “Refah Partisi” (The Welfare Party), whilst the Court held that there had been a violation of Article 11 of the European Convention of Human Rights for all other cases in Turkey.

Therefore, it is important to examine the relevant case-law to analyses different approaches used by the national courts and the ECtHR in dealing with the dissolution of political parties (Özbay, 2015; Hakyemez & Akgun, 2002). The ECtHR mainly refers to Article 11 (freedom of assembly and association), Article 10 (freedom of expression) and Article 9 (freedom of religion) of the Convention for resolving the dissolution of political party cases. Based on its case-law, the ECtHR has made a significant contribution in applying and interpreting Article 11 and other relevant articles of the Convention.

In the a ar, arata , A soy and the People’s Labour Party (HEP) v. Tur ey case, the ECtHR created general principles (European Court of Human Rights, 2002), as follows:

“…a political party may promote a change in the law or the legal and constitutional structures of the State on two conditions: firstly, the means used to that end must be legal and democratic; secondly, the change proposed must itself be compatible with fundamental democratic principles. It necessarily follows that a political party whose leaders incite to violence or put forward a policy which fails to respect democracy or which is aimed at the destruction of democracy and the flouting of the rights and freedoms recognised in a democracy cannot lay claim to the Convention’s protection against penalties imposed on those grounds...”

Since the United Communist Party of Turkey and Others v. Turkey case, the ECtHR also created two standards of measurements in examining political party dissolution cases (European Court of Human Rights, 1998). Firstly, the ECtHR will examine whether there has been interference with the exercise of Article 11 of the Convention. Secondly, the ECtHR will examine whether the interference is justified. According to the ECtHR, the interference is justified if it fulfils three requirements, namely:

1. Prescribed by law;

2. Legitimate aim;

3. Necessary in a democratic society.

In the Refah Partisi (The Welfare Party) and Others v. Turkey case, the ECtHR determined that the exception for freedom of assembly and association, including the dissolving of political parties, shall be construed strictly, with only convincing and compelling reasons being accepted to restrict such parties’ freedom of association. Furthermore, the ECtHR upheld that in determining whether a fraction of Article 11 paragraph (2) exists, the Contracting States have only a limited ‘margin of appreciation’ (Refah, 2003).

Moreover, in the Socialist Party of Turkey (STP) and Others v, Turkey case, the ECtHR interpreted that the right to freedom of expression guaranteed under the European Convention of Human Rights includes the right to advocate ideas or opinions that might offend, shock or disturb other people. In regard to political parties, the ECtHR held that a campaign for changing the legal or constitutional structure of the state is still allowed, but it shall fulfil two conditions.

1. The methods employed for this purpose must in all respects be legal and democratic;

2. The change proposed must itself be compatible with fundamental democratic principles (Socialist Party of Turkey, 2003).

Additionally, the ECtHR stated that it would not be against to democratic principles when political parties have a political proposal that is incompatible with the existing principles and structure of the state. According to the ECtHR, the essence of democracy is to allow any advocacy or discussion of different political proposals, including the proposals that could change the existing structure of a state (Venice Commission CDL-AD, 2011).

In the Herri Batasuna and Batasuna v. Spain case, the ECtHR upheld the Spanish Supreme Court decision to dissolve Herri Batasuna and Batasuna. The courts concluded that there was a link between those political parties with the terrorist organization ETA. The terrorist attacks that happened in Spain for many years were considered a threat to democracy. The ECtHR also reiterated a well-established principle of the Court’s case law, highlighting that there can be no democracy without pluralism. This means that the principal characteristics of democracy shall be up for discussion or debate, without recourse to violence and through a dialogue of various issues, even if it is troubling or disturbing (European Court of Human Rights, 2009).

The ECtHR also dealt with political parties from Germany. Although the Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) v. Germany case was not related to the dissolution of a political party, they ruled that the application was inadmissible due to being ill-founded. This was due to a lack of adequate remedies being available to the NPD who complained about being referred to as both far-right and unconstitutional (European Court of Human Rights, 2016). Nevertheless, it is essential to analyses a recent decision declared by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (Bundesverfassungsgericht, or BVerfG) concerning the Parliament’s request to dissolve NPD, a neo-Nazi party, deemed to advocate a concept aimed at abolishing the existing free democratic basic order (Case No. 2 BvB 1/13).

Although the BVerfG held that the NPD had a clear intention to replace the existing constitutional system with an authoritarian national state, the BVerfG did not dissolve the NPD. This is in addition to believing that the NPD’s main political concept disrespected human dignity as well as being incompatible with the principle of democracy. Using a strict approach to wehrhafte or streitbare Demokratie known as “militant democracy” (Capoccia, 2013; Tyulkina, 2015; Thiel, 2016), the BVerfG believes that the NPD’s endeavours will not be successful.

"While the NPD indeed professes its commitment to aims that are directed against the free democratic basic order and although it systematically acts towards achieving them, which is why its acts constitute a qualified preparation of abolishing the free democratic basic order that it strives for, there are no specific and weighty indications that suggest that the NPD will succeed in achieving its anti-constitutional aims. Neither is there a prospect of successfully achieving these aims in the context of participating in the development of political opinions (aa), nor is it sufficiently discernible that there is an attempt-attributable to the NPD-to achieve these aims by undermining the freedom of participating in the development of political opinions (bb).”

The important cases discussed above are cited many times by the ECtHR or the constitutional courts in European countries when deciding cases on the dissolution of political parties. There is no doubt that the ECtHR has been playing a strategic role in developing the principles and requirements for the dissolution of political party cases.

Conclusion

International human rights instruments and relevant case-law have provided broader perspectives on how other national and international courts dealt with the dissolution of political party cases. Based on the comparative analyses above, the relevant decisions from other jurisdictions on similar issues can be referred to by the Indonesian Constitutional Court for shaping arguments when deciding on the outcome of cases relating to the dissolution of political parties. The Constitutional Court is therefore expected to have a stronger legitimacy and can ensure its compliance with international human rights standards. Using these principles and requirements, the Constitutional Court can deliver more judgments with sound legal reasoning. Given that Indonesia has no experience in dissolving any political party through the judicial process, the role of the Constitutional Court will be crucial in establishing such principles in accordance with the character and background of the legal, social, cultural and political systems in Indonesia.

References

- Asshiddiqie, J. (2005). Freedom of association, dissolution of political parties and the constitutional court. Jakarta: Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia.

- Butt, S. (2015). Constitutional court and democracy in Indonesia.Leiden: Brill-Nijhoff.

- Capoccia, G. (2013). Militant democracy: The institutional bases of democratic self-preservation. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 9(1), 207-226.

- Celep, O. (2014). The political causes of party closures in Turkey. Parliamentary Affairs, 67(2), 371-390.

- Esen, S. (2012). How influential are the standards of the European court of human rights on the Turkish constitutional system in banning political parties? Ankara Law Review, 9(2), 135-156.

- European Court of Human Rights. (1998). United communist party of Turkey and others v. Turkey: Grand chamber, application no 133/1996/752/951.

- European Court of Human Rights. (2002). Yazar, Karatas¸, Aksoy and the people’s labor party (HEP) v. Turkey: Chamber, application no’s 22723/93, 22724/93 and 22725/93).

- European Court of Human Rights. (2009). Herri Batasuna and Batasuna v. Spain: Chamber, application no 25803/04 and 25817/04.

- European Court of Human Rights. (2016). Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) v. Germany: Chamber, application no 55977/13.

- Hakyemez, Y.S., & Akgun, B. (2002). Limitations on the freedom of political parties in Turkey and the jurisdiction of the European court of human rights. Mediterranean Politics, 7(2), 54-78.

- Kogacioglu, D. (2003). Dissolution of political parties by the constitutional court in Turkey judicial delimitation of the political domain. International Sociology, 18(1), 258-276.

- Loewenstein, K. (1937). Militant democracy and fundamental rights. The American Political Science Review, 31(3), 417-432.

- Madinier, R. (2015). Islam and politics in Indonesia: The masyumi party between democracy and integralism. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Moral, M., & Tokdemir, E. (2016). Justices en garde: Ideological determinants of the dissolution of anti-establishment parties. International Political Science Review, 38(3), 264-280.

- Nowak, M. (2005). U.N. covenant on civil and political rights: CCPR commentary. Arlington, VA: N.P Engel.

- Özbay, F. (2015). A comparative study on the criteria applied to the dissolution of political parties by the Turkish constitutional court and the European court of human rights. Human Rights Review, 5(9), 1-19.

- Palguna, I.D.G. (2017). The influence of international law on the Indonesian constitutional court decisions. Presented in ProCuria Program 2017 at The Hague University of Applied Science, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Pasqualucci, J.M. (1995). The Inter-American human rights system: Establishing precedents and procedure in human rights law. The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, 26(2), 297-361.

- Refah, P. (2003). The welfare party and others v. Turkey: Grand chamber, application no’s 41340/98, 41342/98, 413343/98 and 41344/9.

- Roosa, J. (2006). Pretext for mass murder: The September 30th Movement and suharto’s coup d’état in Indonesia. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Safa’at, A. (2011). Dissolution of political parties. Jakarta: Rajawali Pers.

- Socialist Party of Turkey. (2003). Chamber, application no 26482/95.

- Thiel, M. (2016). The militant democracy principle in modern democracies. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tumay, M. (2016). The European convention on human rights: Restricting rights in a democratic society with special to Turkish political party cases. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester.

- Tyulkina, S. (2014). Fragmentation in international human rights law: Political parties and freedom of association in the practice of the UN human rights committee, European Court of human rights and inter-American court of human rights. Nordic Journal of Human Rights, 32(2), 157-175.

- Tyulkina, S. (2015). Militant democracy: An alien concept for Australian constitutional law? Adelaide Law Review, 36(1), 517-539.

- Venice Commission CDL-AD. (2010). Guidelines on political party regulation by OSCE/ODIHR and Venice commission adopted by the Venice commission at its 84th plenary session.

- Venice Commission CDL-AD. (2011). Opinion on the draft law on amendments to the law on political parties of the republic of Azerbaijan, adopted by the Venice Commission at its 89th Plenary Session.

- Venice Commission CDL-INF. (2000). Guidelines on prohibition and dissolution of political parties and analogous measures, adopted by the Venice commission at its 41st plenary session.