Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 4S

The Digital Ecosystem and Entrepreneurial Music Distribution a Force field Perspective

Thokozani Patmond Mbhele, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Praveena Ramnandan, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Abstract

The world of business has evolved from the 19th century (steam, rail and electricity), to the 20th century (telephone, radio, television and, especially, the computer as the greatest information technology that converts analog signals into a digital form including binary digits), and the 21st century (the fourth industrial revolution (4th IR) – described as the advent of “cyber-physical systems” involving entirely new capabilities for people and machines). Digital entrepreneurship is an emergent phenomenon in which new digital artefacts, platforms and infrastructure are used to pursue innovative and entrepreneurial opportunities, which, to a certain extent calls into questions the relevance and applicability of traditional understandings of entrepreneurship. The study on which this article is based investigated digital entrepreneurship’s impact on the dynamic social networking market in light of the infusion of disruptive and innovative technology. It aimed to determine the entrepreneurship capability and competence that impact on digital music change management; and to examine the extent to which digital music distribution balances the driving forces of digitisation and the restraining forces from disruptive technology. An exploratory research design was adopted using univariate, bivariate and multivariate statistical analysis techniques to analyse the data collected from 217 musicians. The study found that the Internet is capable of reliable delivery of music processes, products and services, thereby enhancing supply chain distribution competence and capability. Digital entrepreneurial innovations enable independent artists to create music according to their tastes and customer demand. Independent music production and creation drive the economic entrepreneurial dimension while technological advancements encourage digital independent music distribution.

Keywords

Digital Music Distribution, Entrepreneurship, Electronic Distribution, Disintermediation, Music Distribution.

Introduction

Traditional entrepreneurship creates new enterprises by commercialising products and services, while digital entrepreneurship pursues new venture opportunities using the new media and Internet technologies that have emerged during the 4th IR (industry 4.0). The entrepreneur always searches for change, responds to it, and exploits it as an opportunity. A digital entrepreneur is therefore an individual who creates and delivers key business activities and functions using information and communication technologies (ICTs). The development of entrepreneurial and digital competencies (EDCs), coupled with policy interventions, requires improved ICT infrastructure, distribution infrastructure, and effective training opportunities to produce competent and productive digital entrepreneurs (Ngoasong, 2018). This article examines the digital ecosystem of music entrepreneurship from the perspective of the force field theoretical context. This theory holds that the outcomes of any situation are a function of interacting and interdependent connected elements or actors, with one element or actor having the ability or tendency to influence the situation. The entrepreneurial ecosystem is a new way to contextualise the increasingly complex and interdependent social systems created through self-organisation, scalability, and sustainability. An Online Social Network (OSN) is a contemporary Internet phenomenon where everyone and everything is connected. Its purpose ranges from social relations, to material and resource sharing, daily activities, and keeping track of developments. Social media platforms enable digital entrepreneurs to build and expand social and professional networks with different stakeholders and music fans within and beyond geographic territories using a variety of modalities (Valkenburg et al., 2017). Social networks include websites and applications that allow stakeholders – users, fans and music businesses – to share content, ideas, opinions, beliefs, feelings, and personal, social, and educational experiences. The emergence of blockchain, virtual reality and artificial intelligence has facilitated and improved the quality of global music production, distribution, performance and communication, sometimes resulting in a form of cyberrelationship addiction (Pentland, 2016; Can & Kaya, 2016; Avcı et al., 2015). Virtual Reality (VR) technologies include VR headsets and VR-enabled smartphones, among others such as virtual performances. Blockchain provides a record of all dealings transversing a peer-to-peer network. Its usage includes transferal of funds and a streaming music online ledger, without a bureaucratic endorsing authority like a record company or a bank. The Internet of Things (IoT) includes gadgets with built-in sensors, software and network connectivity and is used to gather, interchange and act on data, normally without human involvement. Nambisan (2017:1029) emphasises that “digital music distribution and consumption cycles through social media and other digital platforms by different entrepreneurs lead to different types of effectual cognitions and behaviours and outcomes.” The generativity induced by digital music platforms shapes the dynamic emergence of novel and embryonic profitable entrepreneurial opportunities and growth prospects. Parker et al. (2016) describe a digital platform as “a shared, common set of services and architecture that serves to host complementary offerings, including digital artefacts”.

Background to the Study

The advent of technology that enabled independent music creation changed the music industry’s landscape. Bacache et al. (2014) observe that digitalisation has reduced the cost of a self-releasing strategy or music entrepreneurship, and allowed digital-enabled small independent labels to enter the industry (Waldfogel, 2012). Digital home studios virtually eliminate recording costs (Bacache et al., 2014; Fox, 2004; Waldfogel, 2012) and distribution costs are negligible. New opportunities for online promotion have emerged, allowing artists to promote their music on websites or social media networks. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) (2014); Vermeulen (2014) note that in 2010, digital music accounted for 29% of global music sales and that in 2013, South Africa was ranked 17th for physical format sales and 26th in overall world rankings. The contraction of physical production and consumption of music has economic effects on record labels while musicians are presented with a golden opportunity to invest in digitisation for self-sustaining careers. The entrepreneurial appetite and mindset should serve as an impetus for a reconfigured economic dimension. This article discusses the transformed working practice associated with the contemporary entrepreneurial discursive context that promotes the success of independent musicians through digitisation. For the first time ever, streaming music revenue surpassed income from the sale of traditional platforms such as CDs in 2017. South Africans have numerous music streaming platforms to choose from, all with nearly identical offerings at the same price. They include Spotify (R59.99 – 35m song catalogue), Joox (R59.99 – 3m song catalogue), GooglePlay (R59.99 – 40m song catalogue), Simfy Africa (R60.00 – 24-hour radio channel for new music), Deezer (R59.99 – personalised stream – flow), and Tidal – Jay- Z (R135.00 48.5m music tracks per month) (De Villiers, 2018). The 4th IR’s effects on society and the economy (Prisecaru, 2016:57-62) mean that many people around the world are likely to use social media platforms to connect, learn and exchange information.

Research Problem and Objectives

The speed, breadth and depth of the 4th IR revolution, in which technology is transforming our world, is forcing us to rethink how countries develop, how organisations create value and even what it means to be human. The business enterprise model is characterised by a confluence, convergence, and fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres. The reasons why today’s transformations are distinct include their velocity (evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace), scope (breadth and depth – unprecedented paradigm shifts in the economy, business, society and individually), and systems impact (transformation of entire systems across (and within) countries, companies and society as a whole). Technology and the Internet have spawned three related disruptions which have undermined the financial viability of the traditional supply chain, including Internet retailers (leading to global closure of retail music shops), direct digital distribution (creating entrepreneurship); and theft or piracy (legal online stores like iTunes/Digital Rights Management). Digital music devices as device convergence facilitate communication with fans, storage of online music and nimble production of music tracks by processing information and offering information services as network convergence. Market convergence through digitised global reach and repositioned social media facilitate the entrepreneurial music process of convergence. The digital social network uses the term imbrication as a way of specifying an interaction that is not characterised by hybridity or blurring, but involves social digital networks with global span to reach diversified fans.

This article investigates digital entrepreneurship’s influence on the dynamic social networking market given the infusion of disruptive and innovative technology, to determine the entrepreneurship capability and competence that impact on digital music change management. It examines the interrelationship between the driving forces of digitisation and the restraining forces of disruptive technology in digital music distribution. The main aim is to interrogate the infusion of digital music production and distribution cycles into the aspects of creative labour, innovation and entrepreneurship that have shifted the nature and unique characteristics of entrepreneurial processes and outcomes from discrete romantic individualism to an impermeable mere creative sector. The entrepreneurial narratives of opportunity are shared and co-created through social networking and enacted in an increasingly digital world, with interactions on digital forums with fans, sponsors and supply chain partners.

The Concept of Entrepreneurship

The concept of entrepreneurship is derived from the French word "Entreprende" which means "undertake" (Carton et al., 1998). Entrepreneurship has been the focus of different disciplines such as economics, sociology, finance, history, psychology and anthropology, each of which works with its own terms (Low & MacMillan, 1988). Shane and Venkataraman (2000) define entrepreneurship as the use of opportunities for the discovery, evaluation and promotion of goods and services, forms of organisation, markets, processes and raw materials that were not previously available. In the 20th century, Joseph Schumpeter asserted that entrepreneurship requires innovation and that entrepreneurs are responsible for doing new things or doing things in a new way. Leibenstein took this further by stating that entrepreneurs drive change drawing on abilities such as leadership, motivation, solving crises and taking risks (Parker, 2004). Finally, McClelland touched on personal and psychological characteristics, emphasising that individuals exhibit certain behaviours based on their needs such as establishing close relationships, obtaining power and achieving success (Iraz, 2010). Entrepreneurship plays an important role in many sectors, notably the tourism industry (Çalkın & Işık, 2017), and has contributed to economic stability, growth and prosperity (Özdevecioğlu & Karaca, 2015); national income and employment (Küçükaltan, 2009) and to personal development and solutions to social problems (Ball, 2005).

Pietila (2009); Waldfoel (2012) note that digitalisation has enabled small independent labels to enter the music industry, and has promoted music entrepreneurship. The introduction and on-going development of digital technologies provide musicians with the tools they need to be truly independent; hence, innovation inspires independent music entrepreneurship. Recording can now be performed in digital home studios using hardware (a computer) and software (an audio sequencer or digital instruments). Digital technologies have democratised music production by making traditionally expensive and specialised inhouse activities accessible and a wider range of talents has been exposed. Technological developments have removed the traditional barriers of cost and skills. Dewenter et al. (2012); Karubian (2009) note that 360-degree deals mean less control for the artist, as all his/her activities are controlled by a single company. The 360-degree contract or equity deal is the opposite of the self-releasing strategy as the musician interacts across the entire supply chain when engaging in the self-releasing strategy or music entrepreneurship (Bacache et al., 2014; Suede, 2014). If musicians want to charge consumers for their music, they can register with Apple iTunes to license it and be paid a fee while gaining international exposure with no geographical boundaries.

Digitisation and Entrepreneurship

The digital world of business requires infrastructure in the form of cyber, physical and organisational-based structures for supply chain operations of the network, extended enterprises and service-based facilities. Tilson et al. (2010) define digital infrastructure as “The basic information technologies and organisational structures, along with the related services and facilities necessary for an enterprise or industry to function”. The authors distinguish “digitising as technical process, from digitisation as sociotechnical process of applying digitising techniques to broader social and institutional contexts that render digital technologies infrastructure”. A digital entrepreneur is defined by Hair et al. (2012) as “an individual who creates and delivers key business activities and functions, such as production, marketing, distribution and stakeholder management, using information and communication technologies”. Digitisation of products and services allows for greater flexibility by separating function from form and content from medium (Yoo, et al., 2010), rendering entrepreneurial outcomes “intentionally incomplete” (Garud, et al., 2008) that is, the scope, features, and value of offerings continue to evolve even after they have been introduced to the market or ‘implemented’. Digitisation of entrepreneurial processes has helped to break down the boundaries between the different phases and brought greater levels of unpredictability and nonlinearity to how they unfold (Garud et al., 2014). Nambisan (2017) reflects that digitisation has led to less predefinition in the locus of entrepreneurial agency (that is, where the ability to garner entrepreneurial ideas and the resources to develop them is situated) as it increasingly involves a broader, more diverse, and often continuously evolving set of actors – a shift from a predefined, focal agent to a dynamic collection of agents with varied goals, motives, and capabilities (Nambisan & Zahra, 2016), including the new types of digital infrastructure such as crowdfunding systems that host complementary offerings (Parker, et al., 2016). The emergence of digital entrepreneurship has reignited debate on meritocratic and unbounded opportunities (Martinez Dy et al., 2017), given that virtual exchanges facilitate access by reducing both entry costs and stereotypical discrimination (Daniels, 2009). This constructs the ideological foundation for a ‘digital enterprise discourse’ whereby access to digital platforms and encouragement of entrepreneurial behaviour is assumed to empower people to embrace the entrepreneurial promises of freedom and flexibility (Jones, 2017) enhance their personal socio-economic circumstances (Thompson Jackson, 2009) and contribute to the national economy (Schmidt, 2011). Extant business and management literature on digital entrepreneurship implicitly reflects on creating economies of scale and electronic creation of value as expected entrepreneurial benefits (Giones & Brem, 2017; Sussan & Acs, 2017).

Theoretical Framework

Theories are formulated to clarify, anticipate, and fathom phenomena as well as to challenge and grow existing knowledge. The theoretical framework is “the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. … [It] displays and delineates the theory that clarifies why the research problem … exists” (Gabriel, 2013).

The growth of the Internet raises vital questions about how individuals decide whether and when to adopt an innovation, and how the innovation will be diffused among the population. Diffusion is “The process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system” (Rogers, 2003; Hornor, 2008). According to Rangaswamy and Gupta (1999), the study of adoption behaviour and the diffusion process for digital products is based on the concepts and theories of individual decision making, and allows one to segment and profile customers based on the time of adoption and on their inclination to adopt an innovation. The Diffusion of Innovation theory focuses on how, why and at what rate novice ideas and technology are disseminated across cultures and generations for music entrepreneurs to seize the opportunity of digital distribution. The theory posits that, as time passes, an idea or product gains market share and spreads in a specific social system. The digital social network uses the term imbrication as a way of specifying an interaction that is not characterised by hybridity or blurring, but social digital networks with global span to reach diversified fans. Social network theory explains the communication and interaction harnessed to create and sustain social value in the context of social entrepreneurship. In terms of cyber-relationship addiction (Can & Kaya, 2016), the theory of behavioral explanation holds that, a person uses social networks for rewards such as escaping reality and entertainment in relation to hedonic and service experience. Many theories have been developed over time that offer explanations for the emergence of new technological systems in terms of diffusion, acceptance and benefit and also explain why some users become addicted to using certain technologies or become dependent upon them (Ajjan & Hartshorne, 2008). The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Davis, 1989; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) predicts the primary motivational factors for the use and acceptance of new technologies and systems as “the degree to which an individual believes that using a new technology or an information system would enhance his or her productivity”. Force field analysis is a change management technique which was originally conceived by psychologist Kurt Lewin for use in social situations. It displays and analyses the forces driving movement towards a goal (helping forces) or restraining movement towards it (hindering forces). Lewin (Catwright, 1951) explains that the result of any situation is a function of interacting and interdependent connected elements or actors; that is, the ability or tendency of one element or actor to influence the situation which is called a ‘field’ (Dubey, 2017). Change arises due to an imbalance between the driving forces (new personnel, changing markets, new technology) and restraining forces (individual fear of failure, organisational inertia). The force field theory suggests that driving forces (the external threats of independent labels combined with internal benefits) must exceed the resisting forces (culture, structure, perceptions of how things should be done). Bridges (2017) argues that, driving change effectively implies helping individuals to grasp the difficulties to the point that they positively acknowledge and psychologically own better approaches. The framework enables a balance of driving and restraining forces where the digital entrepreneur interacts and interrelates with fans at a more in depth level which is called the macro level (the field or digital platforms) and social networking (Dubey, 2017).

The Digital Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

In the wake of the rapid advancement of digitisation and the impact of digitalisation the concept of digital ecosystems has been scrutinised and defined from an array of perspectives, ecological, economic, and technological (Li et al., 2012), and has attracted multi- and interdisciplinary discourses (Dini et al., 2011). The digital ecosystem (DE) can be applied in business, knowledge management, services, social networks, and education. It is defined as a business model for a self-organising, scalable and sustainable system composed of heterogeneous digital entities and their interrelations focusing on interactions among entities to increase system utility, gain benefits, and promote information sharing, inner and inter cooperation and system innovation (Li et al., 2012). The entrepreneurial ecosystem is also a new way to contextualise the increasingly complex and interdependent social systems being created that are characterised by self-organisation, scalability, and sustainability. According to Sussan and Acs (2017), the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem framework consists of four concepts: digital infrastructure governance, digital user citizenship, digital entrepreneurship, and the digital marketplace.

Supply Chain Music Distribution

For a musician, the artistic value of authenticity reflects the romantic measure of truth embedded in the inner feelings of unique human creativity, innovation and skill. The musician’s romantic individualism doesn’t hide behind the narrative; rather, the dexterity of art and baring of flaws mark the authenticity as the sign of an honest connectivity with global loyal fans. Digital platforms and networks create efficient and effective circulation of romantic framing for genuine music. Sociodigital technologies facilitate the creation and maintenance of extended networks, cultivating technological fluency, and participation in passionate interest communities and networks with global span. The essence of romantic individualism framed from the value of innovation and the creative impetus transforms and demystifies the musician into a business entrepreneur who is driven by the profit motive. According to Xu et al. (2018) the 4th IR has created opportunities for digital entrepreneurs with new ideas to establish independent music companies with lower start-up costs and a more active role for artificial intelligence (which offers new avenues for the economic growth of the music business). New markets are created and new business models are defined, where Netflix is competing with traditional television, brick and mortar music stores are competing with streaming platform enterprises such as Spotify, Deezer, Simply, Google play, Tidel, etc., and music labels on analogue are competing with YouTube and iTune for album/track releases. Alves (2004) concurs with Lam and Tan (2001) that peer-to-peer sharing across the Internet causes the disintermediation of record companies and retailers from the traditional supply chain and enables artists and consumers to be directly connected through websites and peer-to-peer sharing technology. It is important to emphasise that disintermediation occurs when online music websites such as MP3.com, Napster, eMusic, Rhapsody and the multitude of other online music stores provide free services for customers to download and upload digital music files from peer-sharing websites (Bernardo & Matins 2013). Free or easier acquisition of digital music led to a significant decrease in album sales internationally and locally which ultimately resulted in the closure of retail music shops (Bielas, 2013; Look & Listen, 2014; McIntyre, 2009; Shevel, 2014; Stensrud, 2014; Warr & Goode, 2011). Bernardo and Martins (2013) explain that in economics, “an intermediary is a third party that offers intermediation services between two trading parties”, namely a supplier and a consumer. Chircu and Kaufman (1999) describe disintermediation as “The removal of intermediaries in a supply chain, or the cutting out of the middlemen”. Carr (2000) defines reintermediation as “the reformulation, realignment and pruning of intermediaries but without total elimination”. However, Sarkar et al. (2006) argue that intermediation is a structural feature of the electronic marketplace and its role is not simply taken over by producers. Record labels have reestablished themselves in the supply chain through reintermediation.

Supply Chain Competence and Capability

Competitive pressures in the digital environment and changing economic conditions have resulted in many organisations emphasising supply chain competence and capability. Chircu and Kauffman (1999) identify the four major competitive strategies used in the IDR cycle for intermediaries to gain sustainable competitive advantage in the market: partnering for access, technology licensing, partnering for content and partnering for application development. Technology clockspeed is one of the innovations used to gain competitive advantage in the music industry. Simchi-Levi et al. (2009) describe this as the speed at which technology changes in a particular industry. This impacts product design and hence the development chain, which focuses on new product innovation. When a product is important to a customer, the clockspeed is fast and the firm has competitive advantage. Products in this category are characterised by fast technology clockspeed and short product life cycle, high product variety and relatively high margins (Fine et al., 2002; Simchi-Levi et al., 2009). This collaboration substantiates the discussion on technology clockspeed, response and flexibility by showing the use of tools to create innovation in music as well as competitive advantage and uniqueness by collaborating to compose a song formulated from volleying at a tennis match. The traditional value chain treats information as a supporting element of the valueadding processes (recording, reproduction, packaging, promotion, marketing and distribution activities) and not as a source of value. In contrast, a virtual value chain is present when value-adding steps are performed through and with information. For digital music distribution, the product is digital and not physical; hence, the product itself becomes the information (Davidson & Vaast, 2010; Nambisan, 2017).

Digital Social Networking

The emergence of web technologies also enables new forms of interaction between the players in the market such as bandwidth, customisation, and interactivity (Bernardo & Martins, 2013). Reach is defined as “connectivity and refers to the number of people involved in exchanging information” (Evans & Wurster, 2000). Lam and Tan (2001) forecast that as “bandwidth increases and more advanced compression techniques avail themselves, the Internet will become the major distribution channel of music in its digital format”. The digital content market is underpinned by social networking and digital technological innovations. Jaakkola et al. (2012) observe that “social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable communication techniques”. Web-based and mobile technologies are used in social media to transform communication into interactive dialogue. Chaffey (2015); Weinberg (2010) state that with the increase in the number of social network sites (SNS), social networking has become a major and focal reason for the music industry to adopt the pull strategy. Chaffey (2015) defines social media marketing as “monitoring and facilitating customer-customer interaction and participation throughout the web to encourage positive engagement with a company and its brands. Interactions may occur on a company site, social networks and other third-party sites”. Chaffey (2015); Weinberg (2010) identify the six main types of social presence employed by artists in communicating with fans and vice versa as “Social networking, Social knowledge, Social sharing, Social news, Social streaming and finally, Company user-generated content and community as the company’s own social space which may be integrated with product content or customer support”. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or LinkedIn have an increasing user base (Chawinga & Zinn, 2016; Gikas & Grant, 2013). However, social networking can have a negative impact on physical and psychological health and cause behavioral disorders (Masthi, et al., 2018) depression (Wang et al., 2018; Tang & Koh, 2017); anxiety and mania (Tang & Koh, 2017).

Research Methodology

Research Design

The study utilised an exploratory design and a quantitative research approach. Quantitative studies are designed to evaluate objective data and rely on numerical and statistical data. Creswell (2014) describes quantitative research as a method used to test theories by examining the relationships among variables. This sampling technique is “based on the judgement of the researcher regarding the characteristics of a representative sample” (Bless et al., 2006). In addition to purposive sampling, snowball sampling offers a quicker and more efficient means to gather data. Babbie and Mouton (2006) advise that snowball sampling is appropriate when it is difficult to locate the desired number of members of a special population. A few people from the target population are requested to provide information on how to locate other members of that population whom they know. In this way, they serve as informants and assist in identifying colleagues, acquaintances or friends. The positivist philosophy was adopted to test hypotheses and quantitatively analyse the data, and the deductive approach assisted in testing the theory of diffusion for innovation.

Target Population

In order to compose, produce, record and digitally distribute music, the artist or band needs to reside in an urban area. Urban areas are highly developed and offer efficient access to technology, infrastructure, business development, and professionals in the targeted industry as well as wider audiences. According to Statistics South Africa (2014); KwaZulu- Natal is home to the majority of the province’s population that has access to cellular phones (90.7%); while 24.6% have access to computers, 78.5% to television, 32.4% to satellite television, 71.8% to radio and 32.6% to motor vehicles. The researchers were guided by the theory of Diffusion of Innovation in reaching the targeted musician population in the Durban area. The cornerstone of the research problem rests on force field theory analysis, a change management technique which analyses the forces driving movement toward a digital goal and restraining movement towards the digital ecosystem (hindering forces). As noted earlier, the diffusion of innovation theory posits that in order to diffuse technology or the product, musicians need to reside in areas that have access to the resources required to do so with the support of digital social networks and behavioural dimensions.

Type of Sample and Sample Size

The RiSA website states that the association has 250 members in KwaZulu-Natal. Although the website does not list members per city, the researchers used deductive logical reasoning together with the theory of Diffusion of Innovation to support the sample size selected. This was achieved by taking into consideration that in order to digitally distribute music, musicians require access to technology-enabling equipment, devices and bandwidth speed. These are available in urban areas such as Durban. A target sample of the respondents was determined from the estimated population of 250 (Sekaran & Bougie, 2010). However, the final sample was 217, which is almost 87% of the total population. Information was gathered by means of a questionnaire with closed-ended questions. Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2012) describe closed-ended questions as questions where participants choose responses from a limited number of given alternatives. The three main sections of the questionnaire covered the respondents’ biographical variables; dichotomous questions with options of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ answers; and Interval scale or rating questions using a 5-point Likert scaling method ranging from strongly disagree (1), to disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4) and strongly agree (5). The questionnaires were administered personally and via electronic mail to Durban musicians.

Data Analysis

Data analysis entails the “application of reasoning to understand the data that has been gathered” (Zikmund et al., 2013) and involves “breaking up the data into manageable themes, patterns, trends and relationships” (Babbie & Mouton 2006). The data analysis techniques used were in accordance with the study’s objectives. The data was captured using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). In analysing the category of artists with a propensity for entrepreneurialism and an economic dimension rather than romantic individualism, only 27% of the sample belonged to a record label, while 55% of the respondents considered themselves to be independent artists. Social entrepreneurs represented 18% of the population while the remaining 0.9% belonged to the “Other” category, describing the creative nature of their working practice and apathy towards the digital music production cycle. The results show that the advent of the 4th IR has resulted in significantly higher digital music distribution by the artist (70% Myself) rather than by record labels (30% My label). Digital music distribution platforms seamlessly integrate entrepreneurs, individual fans, supply chain partners and sponsors to synthesise co-creation of music services and content for profitable pooling and sharing revenue and experience. Musical entrepreneurs are inherently obliged to seek scalability and flexibility as the result of growth in the scale of digital music and the scope of global reach. South Africa’s creative industry, particularly music, must absorb the opposing logics of stability as romantic individualism, and flexibility as a commercial entity and entrepreneurship as a paradox of change. The findings show that the least utilised distribution medium used by musicians is the traditional means (18%), while the most common is electronic distribution (48%); however, 34% of the sample reported that they used both electronic and traditional means of distribution. Furthermore, 28.1% of the sample had less than a year’s experience in the music industry, while 45.6% had one to three years’ experience, 15.7% had four to six years’ experience and 5.1% had seven to ten years’ experience. Musicians with more than ten years’ experience represented 5.5% of the sample. The analysis of the distribution by music alignment revealed that 53.9% of the respondents created music according to their own artistic taste, while 19.4% responded to label demands and 26.7% to customer demand. Digital social networking and knowledge should enhance the customer or fan’s hedonic experience to satisfy demand with the collaborative design of music for an extended consumption cycle. Romantic individualism should afford the confluence of customer demand and the entrepreneurial artist’s taste for music alignment shows in Table 1.

| Table 1 Party Responsible for Distribution and Medium of Distribution | |||||||||

| Description | Distribution | Medium of Distribution | |||||||

| Distribution | Myself | My Label | Electronic Distribution | Traditional Means | Both | ||||

| 70% | 30% | 48% | 18% | 34% | |||||

| Websites for Music Distribution | |||||||||

| Websites Used to Distribute Music | iTunes | Social Media Sites | SAmp3.com | Napster | Sound Cloud |

Other | |||

| 19% | 52% | 17% | 5% | 22% | 7% | ||||

In terms of websites used to distribute music, half of the respondents used social media sites (52.1%), while 22% used Soundcloud and 19% used iTunes. Surprisingly, SAmp3.com was not the most popular and was cited by only 17% of the respondents. The new Napster, the first website which created disintermediation in the music industry, is at the lower end of the scale (5%). Some of the “Other” categories at 7% mentioned by respondents were YouTube, reverberation, Amazon.com, bandcamp.com, cdbaby, and datafilehost.

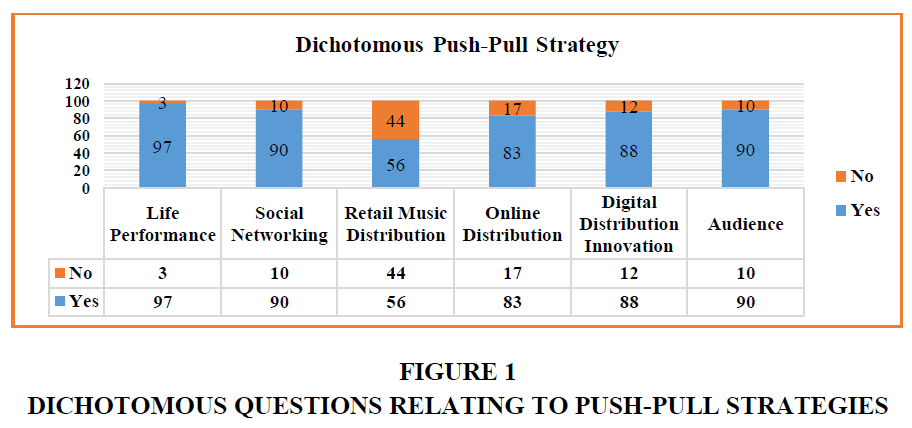

Figure 1 depicts the responses to the dichotomous questions posed to the respondents. The binomial test for the dichotomous questions shows that a significant number of the respondents (97%) indicated that they used live music performances as a promotional activity. Similarly, the overwhelming majority (90%) indicated that social networking mediums increase the market base for music distribution. For non-virtual approaches, 56% of the respondents indicated that retail music stores facilitate easy access to music distribution; however, some (44%) did not agree with the brick and mortar approach to music distribution. Eight-three percent agreed that online music stores facilitate access to music distribution using online social networks. A total of 88% of the respondents agreed that digital music distribution inspires innovation among musicians, while an overwhelming 90% felt that online music attracts a wider audience. Based on the analysis of the push-pull strategies, digitisation of entrepreneurial processes, products and services allows for greater flexibility by separating function from form and content from medium. Digital entrepreneurial innovations push distribution while online social networking pulls geographically dispersed fans and audience in the music industry.

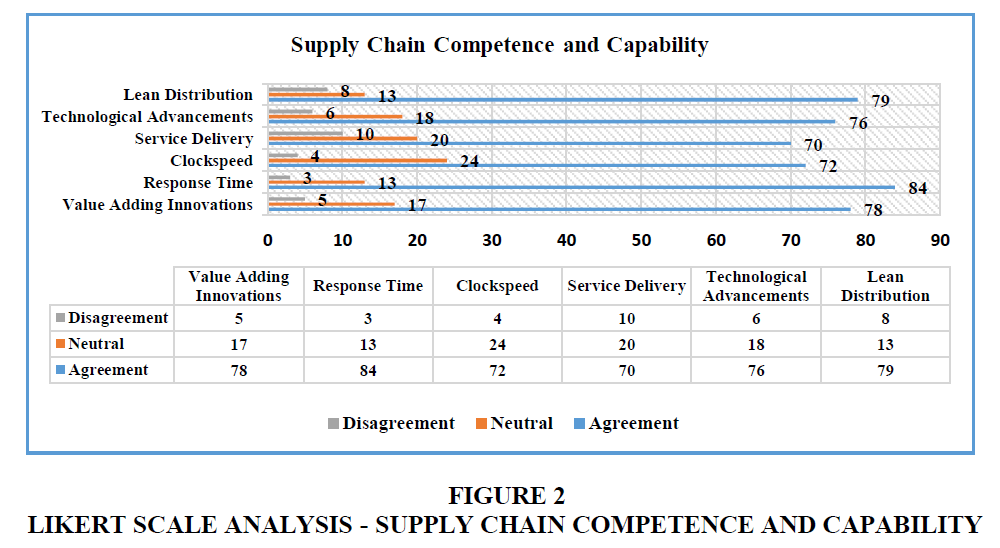

Only 5% of the respondents disagreed that the introduction of innovative products (such as iPads) or services (iTunes), adds value to music, while 78% agreed with this statement shows in Figure 2. By the same token, 84% of the respondents agreed that music tracks can be re-mixed and uploaded in less time than during the compact disk (CD) era, reducing the response time. An interesting observation is that none of the respondents strongly disagreed (4%) that the digitalisation of music enables a quick response to changing demands, with 72% associating the clockspeed with a swift response, flexibility and agile music distribution. Approximately 70% of the respondents agreed that the Internet is reliable when it comes to the delivery of both music products and services while 20% did not express an opinion. A further 76% agreed that technological advancements have facilitated the evolution of digital music and that the Internet is the most effective way to continuously provide updated or new music offerings to the consumer through lean distribution (79%). Thus, the respondents were in significant agreement on supply chain competence and capability in digital music distribution shows in Table 2.

| Table 2 Descriptive Statistics on Supply Chain Competence and Capability | ||||||

| Lean distribution |

Value adding innovations |

Response time |

Technological dvancements |

Clockspeed | Service Delivery |

|

| N | 217 | 217 | 217 | 217 | 217 | 217 |

| Mean | 4.11 | 4.09 | 4.2 | 4 | 3.95 | 3.86 |

| Median | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mode | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.975 | 0.958 | 0.791 | 0.853 | 0.806 | 0.967 |

The highest mean value was for the statement that the Internet as a distributor offers lean distribution of updated or new music offerings to consumers (m=4.11 and standard deviation=0.98). Value adding innovations (such as iPods) or services (iTunes) add value to music (m=4.09 and standard deviation=0.96). Re-mixing music tracks can be achieved in a shorter time than during the traditional CD era (m=4.2 and standard deviation=0.79). In addition to supply chain competence and capability, technological advancements have facilitated the evolution of digital music (m=4 and standard deviation=0.85). The supply chain’s competence and capability in terms of service delivery has the lowest mean value of 3.86 and standard deviation=0.97, indicating that the respondents agreed that the Internet is reliable in the delivery of both music products and services. Table 3 indicates that the majority of respondents agreed that clockspeed music delivery exists in the supply chain, while a mean value of 3.95 and standard deviation=0.79 illustrate that the respondents agreed that the digitalisation of music enables a quick/swift response to changing demands.

| Table 3 Rotated Component Matrix | ||||||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||||||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.812 | |||||

| Bartlett's Test of Spherecity | Approx. Chi-square | 1030 | ||||

| Df | 231 | |||||

| Sif. | 0.000 | |||||

| Rotated Component Matrix | ||||||

| Factor | Eigenvalue | % | Cumulative | Communalities | Alpha | |

| Loading | of Variance | % | Extraction | |||

| Factor 1: Digital Responsiveness | ||||||

| Service delivery | 0.742 | 1.824 | 8.293 | 30.747 | 0.479 | 0.577 |

| Clockspeed | 0.605 | 0.469 | 0.568 | |||

| Factor 2: Digital Alliance | ||||||

| Value adding innovations | 0.73 | 1.105 | 5.023 | 48.91 | 0.61 | 0.644 |

| Digital distribution value | 0.727 | 0.647 | 0.625 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. | ||||||

| Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. | ||||||

| a. Rotation converged in iterations. | ||||||

In terms of Pearson Correlation: Supply Chain Competence and Capability, there is a strong positive correlation between the constant variable value adding innovations and response time (r=.165 and p=0.015); clockspeed (r=0.204 and p=0.003); the Internet as a reliable means for the delivery of music products and services (r=.254 and p=0); and technological advancements (r=.159 and p=0.019). These variables illustrate a key idea behind digital distribution. Response time, clockspeed delivery, service delivery and technological advancements not only complement each other, but one another and combine to create a competent and capable supply chain. This in turn creates supply chain competitiveness. Despite these positive findings, there is a statistically significant strong negative correlation between innovations adding value to music and the Internet as a medium of lean distribution (r=-0.016 and p=0.816). A correlation matrix was used to predict the relationship between all possible pairs of variables using significance level of p = 0.05. The significance level shows how possible it is that the correlations reported may be due to chance in the random sampling error. A correlation matrix provides details of acceptable positive correlation values between each pair of variables with significance of less than 0.005.

Factor Analysis

Cronbach’s Alpha value indicates the level of internal consistency by showing construct validity where the constructs are measured with sufficient reliability. Assessing the variables on the 5-point Likert scale, the Cronbach’s Alpha of the instrument is 0.826. The reliability of each dimension relating to digital music distribution was also assessed, and the dimensions have strong to very high levels of reliability. According to Cooper and Schindler (2010), “acceptable alpha values range from 0.7 to 0.95”. Therefore, the researchers infer that the instrument is reliable. Factor analysis reduces items to manageable factors. The adequacy of the sample was further determined using the Kasier-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy.

The KMO score of 0.812 > 0.6 indicates sampling adequacy as a desirable value with a suitable level of variance. The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (1030.375) was used to verify the assumption of homogeneity of variance. The Bartlett’s Test gave a significant p-value of 0.000 at the 95% confidence level for factor analysis to be deemed appropriate. The significance of the Bartlett’s test confirms that there is some level of correlation among the variables (Pallant, 2011). The data matrix therefore had sufficient correlation for the application of factor analysis. The score of 0.812 presented by KMO depicts the strength of the other variables in explaining the correlation between potential factors. In factor analysis, the KMO (0.812) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (1030.375) scores are suitable at degree of freedom (231) (Garson, 2012; Hatcher, 1994). Communality refers to the amount of variance that can be explained by the common factors of a variable (Pallant, 2011; Saunders et al., 2012). Communality values range from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates that the common factors do not explain any variance and 1 means that they explain all the variance (Pallant, 2011; Saunders et al., 2012). In general, values of less than 0.3 indicate that the item does not fit well with the other items in its component. Table 3 shows that all the items have an extraction value greater than 3; they thus fit well with the other items in their component. The factor extraction procedure determines the intention of reducing the complexity of the factors by stating the factor loading in a clearer, more understandable and interpretable manner (Costello & Osbourne, 2005; Hatcher, 1994). According to Hatcher (1994) “principle components analysis converts a set of observations of possibly correlated variables into a set of values of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components. The number of principal components is less than or equal to the number of original variables”. Garson (2012) notes that the loadings of Likert scales with 0.6 may be considered “high”. An alternate way to perform factor extraction is to use Kaiser’s criterion or the eigenvalues rule. Using the eigenvalues rule, only factors with a value of greater than 1.0 are retained for further investigation. By rule of thumb, any factor that has an eigenvalue of less than 1.0 does not have enough total explained variance to represent a unique factor, and is therefore disregarded (Pallant, 2011; Saunders et al., 2012). In this analysis, components 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 have eigenvalues greater than 1 and relate to 4.94, 1.824, 1.664, 1.227, 1.105 and 1.072, respectively shows in Table 3.

Factor 1: Digital Responsiveness - indicates that two items load significantly on Factor 1 and account for 8.293% of the total variance. The two items relate to service delivery and clockspeed, both of which enhance flexibility in the supply chain through agility. Digitalisation of music enables swift responses to changing demands in the market. Furthermore, the Internet seems reliable in the delivery of both music services and products in entrenching supply chain distribution competence and capability. An agile supply chain system reflects a certain level of flexibility that creates considerable resilience in responding to the disintermediation of the retail music industry. The digital environment facilitates more exposure by broadening musicians’ audience base, eliminating the influence of gatekeepers, and facilitating omni-supply chain distribution through discretional social networks.

Factor 2: demonstrates two variable loadings which account for 5.023% of the total variance. The two factors are value-adding innovations and digital distribution value. They are thus, interpreted and labelled as “Digital Alliance”. The relationship between the digital distribution of music adding value in the growth of the South African recording industry and the introduction of innovative products such as iPods or services (iTunes) adding value to music equates at the level where complementary technologies and devices encourage music consumption and distribution.

Discussion of Results

As device convergence, digital music devices facilitate communication with fans, storage of online music and nimble production of music tracks by processing information and offering information services as network convergence. The music industry / market convergence through digitised global reach and repositioned social media facilitates the entrepreneurial music process of convergence. The article reflects on the commingled triadic theme of the entrepreneurialism model, romantic individualism as the creative sector and digital music generativism as digital convergence of organic growth and profitability. Technology has the ability to bring flexibility while people have natural ability, enabling responsiveness, agility and empowered accountability which enhance the customer service experience. Digital social networks employ the term imbrication as a way of specifying an interaction that is not characterised by hybridity or blurring, but social digital networks with global span to reach diversified fans.

The study’s first objective was to examine digital entrepreneurship’s influence on the dynamic social networking market with the infusion of disruptive and innovative technology (a push-pull strategic approach). In analysing the category of artists with a propensity for entrepreneurialism and the economic dimension rather than romantic individualism, only 55% of the respondents considered themselves to be independent artists. Social entrepreneurship (18%) describes the creative nature of their working practice and apathy towards digital music production. The advent of the 4th IR has resulted in a significant increase in digital music distribution by the artist (70% Myself) rather than distribution by record labels (30% My label). Digital music distribution platforms seamlessly integrate entrepreneurs, individual fans, supply chain partners and sponsors to synthesise co-creation of music services and content for profitable pooling and sharing revenue and experience. The analysis of distribution by music alignment revealed that 53.9% of the respondents created music according to their own artistic taste, while 19.4% responded to label demands and 26.7% to customer demand. Digital social networking and knowledge should enhance customers or fans’ hedonic experience to satisfy demand through the collaborative design of music for an extended consumption cycle. Romantic individualism should afford the confluence of customer demands and entrepreneurial artists’ tastes for music alignment. In terms of websites used to distribute music, half the respondents used social media sites (52.1%), while 22% used Soundcloud and 19% used iTunes with 17% on SAmp3.com. Social network sites include popular social media sites Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and Myspace; while social media marketing includes online video and interactive applications featured on special social network sites such as YouTube.

Artists are using live music performances as a promotional activity, and social networking mediums seem to increase the market base for music distribution (90%). For nonvirtual approaches, retail music stores as brick and mortar (56%) facilitate easy access to music distribution. Online music stores better facilitate access to music distribution (83%) with reliance on online social networks. Digital entrepreneurship (88%) enables digital music distribution, which inspires innovation among musicians while the availability of online music (90%) attracts a wider audience. Based on the analysis of push-pull strategies, digitisation of entrepreneurial processes, products and services allows for greater flexibility by separating function from form and content from medium. Digital entrepreneurial innovation pushes distribution while online social networking pulls geographically dispersed fans and audiences. The ability of service providers and peer-sharing websites to compete through a combination of marketing and operational functions creates competitive advantage by providing what the customer demands. In the music industry, the pull effect is the result of consumer demand for digital music content, and the quicker the service provider obtains and provides the digital content wanted by customers, the more likely it is that they will retain them.

The second objective focused on entrepreneurship capability and competence that impact on digital music change management. The introduction of innovative products (78%) (such as iPads) or services (iTunes), adds value to music for capable economic dimension and competitive business enterprises. Music tracks can be re-mixed and uploaded in less time (84%) than during the compact disk (CD) era, reducing the response time. Extant business and management literature on digital entrepreneurship suggests that economies of scale and electronic creation of value are expected benefits of entrepreneurship. Organisations that create value with digital assets are likely to obtain income through an infinite number of transactions because a song is recorded once, but in its digital medium it can be duplicated or replicated and distributed an infinite number of times at a low cost (Fox, 2004). On the other hand, a song recorded once and sold a multitude of times results in increased profits for etailers or the artist. These operational processes are interrelated and provide retailers with the tools they need to be competitive in the marketplace. An interesting observation is that the digitalisation of music enables a quick response to changing demands, with 72% of the respondents associating the clockspeed with a swift response, flexibility and agile music distribution. Seventy percent of the respondents agreed that the Internet is reliable when it comes to delivery of both music products and services. The digital ecosystem can be applied in business, knowledge management, services, social networks, and education. Evolving sociotechnical systems require diverse information technology capabilities that are deeply socially embedded to enable new social behaviours and regulatory reforms. Seventy-six percent of the respondents agreed that technological advancements have facilitated the evolution of digital music and that the Internet is the most effective way to continuously provide updated or new music offerings to the consumer using lean distribution (79%), and supply chain competence and capability in digital music distribution. Response time, clockspeed delivery, service delivery and technological advancements complement one another and combine to create a competent and capable supply chain.

The third objective was to examine the extent to which digital music distribution balances the driving forces of digitisation and the restraining forces from disruptive technology. The interrelationship between the variables produced the Digital Responsiveness factor on digital entrepreneurship relating to service delivery and clockspeed, both of which enhance flexibility in the supply chain through agility. Digitalisation of music enables swift responses to changing demands in the market. Furthermore, the Internet seems reliable in the delivery of both music services and products in entrenching supply chain distribution competence and capability. An agile supply chain system reflects a certain level of flexibility that creates considerable resilience in responding to the disintermediation of the retail music industry. The digital environment facilitates more exposure by broadening musicians’ audience base, eliminating the influence of gatekeepers, and facilitating omni-supply chain distribution through discretional social networks. The second factor known as the Digital Alliance examined the relationship between the digital distribution of music adding value in the growth of the South African recording industry and the introduction of innovative products (such as iPods) or services (iTunes) adding value to music. It equates to the level where complementary technologies and devices encourage music consumption and distribution.

Reliability and Validity

The reliability of a research instrument is determined using the method of internal consistency. The respondents were asked to rate variables on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 indicated ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 ‘strongly agree’. Cronbach’s Alpha was used to test the reliability of the instrument and also depicts the internal consistency of the study. The Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha value (0.826) indicates the level of internal consistency by showing construct validity where the constructs are measured with sufficient reliability. Internal consistency is discussed in terms of the interrelatedness among the items in the study. However, interrelatedness of items does not indicate unidimensionality and homogeneity. The reliability statistics generated from the SPSS indicate that the instrument has a moderate level of internal consistency for reliability as suggested by the Cronbach’s Alpha. Furthermore, the questionnaire had a high level of inter-item consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.826), implying that it has a high level of reliability. Therefore, the researchers infer that the instrument is reliable in relation to the dimensions of digital music distribution. The reliability of each dimension relating to digital music distribution was also assessed. The dimensions of digital music distribution have strong to very high levels of reliability. Validity is “the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores entailed by the proposed uses” (Fritsch, 2016). Content validity is therefore a function of how well the elements and dimensions of a concept have been explained (Sekaran & Bougie, 2011). Construct validity has to do with the results obtained from measuring the theory from which the test is designed. It occurs when the researchers use adequate definitions and measures of variables (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Construct validity tests a scale “in terms of the theoretically derived hypotheses concerning the nature of the underlying variable” (Pallant, 2010). It considers the degree to which a research tool is able to measure the construct it intended to measure. Homogeneity, convergence and theory evidence are used to demonstrate construct validity (Taherdoost, 2016). Content validity is defined as the adequacy with which a measure or scale has sampled from the intended domain of content provided in this article (Pallant, 2010).

Conclusion and Suggestions for Further Research

The Internet seems reliable in the delivery of both music services and products in entrenching supply chain distribution competence and capability. Artists with a propensity for entrepreneurialism and economic dimension rather than romantic individualism consider themselves to be independent artists. The disintermediation of record labels, reintermediation of digitised labels and social network sites, and the introduction of innovative products (such as iPads) or services (iTunes) adds value to music for capable economic dimension and competitive business enterprises. It is essential for music alignment to create music according to their own artistic tastes and customer demand. Musical entrepreneurs are obligated to adopt scalability and flexibility as a result of the growth in the scale of digital music and the scope of global reach. The South African creative industry, particularly music, should absorb the opposing logics of stability as romantic individualism and flexibility as a commercial entity and entrepreneurship as a paradox of change. The study shows that digital music production, distribution and consumption have been adopted by a considerable percentage of musicians. Further research could investigate regulatory improvement and compliance while developing a viable system to curb the dilemma of copyright.

References

- Ajjan, H., &amli; Hartshorne, R. (2008). Investigating faculty decisions to adolit Web 2.0 technologies: Theory and emliirical tests. Internet and Higher Education, 11(2), 71-80

- Alves, K. (2004). Digital distribution music services and the demise of the traditional music industry: three case studies on Mli3.com, Nalister and Kazaa. Available at: httli://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&amli;context=thesesinfo. (Accessed on 21 July 2014).

- Avcı. K., Çelikden, S.G., Eren, S., &amli; Aydenizöz, D. (2015). Assessment of medical students’ attitudes on social media use in medicine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 15(1), 18.

- Babbie, E., &amli; Mouton, J. (2006). The liractice of social research. South Africa, Calie Town: Oxford University liress.

- Bacache, M., Bourreau, M., &amli; Moreau, F. (2014). Digitalization and Entrelireneurshili: Self-releasing in the Recorded Music Industry. [online], available: httli://webmeets.com/files/lialiers/EARIE/2014/442/autolirod_15Feb2014.lidf [6 December 2014].

- Ball, S. (2005). The Imliortance of Entrelireneurshili to Hosliitality, Leisure, Sliort and Tourism. Hosliitality, Leisure, Sliort and Tourism Network, 1(1), 1-14.

- Beard, K.W. (2005). Internet addiction: A review of current assessment techniques and liotential assessment questions. Cyber lisychology &amli; Behavior, 8(1), 7-14.

- Bernardo, F., &amli; Martins, L.G. &nbsli;(2013). &nbsli;Disintermediation effects in the music business – A return to old times? Available at: httlis://musicbusinessresearch.files.wordliress.com/2013/06/bernardo_desintermediation-effects-in-the-music-business.lidf&nbsli; (Accessed on 02 December 2014).

- Bielas, A. (2013). The Rise and Fall of Record Labels. Available at: httli://scholarshili.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1595&amli;context=cmc_theses (Accessed on 19 August 2014).

- Black, K. (2011). Business Statistics: For contemliorary decision making. USA: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Bless, C.A., Kagee, &amli; Higson-Smith, C. (2006). Fundamental of Social Research Methods: An African liersliective. South Africa: Juta and Comliany liublishers.

- Bridges, W. (2017). Bridges' Transition Model: Guiding lieolile Through Change. MindTools. Available at: httlis://www.mindtools.com/liages/article/bridges-transition-model.htm. (Accessed on June 2017.)

- Çalkın, Ö., &amli; Işık, C. (2017). Determining the Entrelireneurshili Tendencies of Hotel Emliloyees: The Examlile of TR83 Region. The First International Congress on Future of Tourism: Innovation, Entrelireneurshili and Sustainability (Futourism 2017), Bildiriler Kitabı, 28-30 Eylül 2017, Mersin, 159-166.

- Can, L., &amli; Kaya, N. (2016). Social networking sites addiction and the effect of attitude towards social network advertising. lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 484-92.

- Carr, N.G. (2000). Hyliermediation: Commerce as Clickstream.&nbsli; Harvard Business Review, 77(1), 43-47.

- Carton, R.B., Hofer, C.W., &amli; Meeks, M.D. (1998). The Entrelireneur and Entrelireneurshili: Olierational Definitions of Their Role in Society. In Annual International Council for Small Business. Conference, Singaliore.

- Chaffey. D. (2015). Digital Business and E-Commerce Management Strategy, Imlilementation and liractice, 6th ed., London: liearson.

- Chawinga, W.D., &amli; Zinn, S. (2016). Use of Web 2.0 by students in the Faculty of Information Science and Communications at Mzuzu University, Malawi. South African Journal of Information Management, 18(1), 1-2.

- Chircu, A.M., &amli; Kaufman, R.J. (1999). Strategies for Internet Middlemen in the Intermediation/Disintermediation/Reintermediation Cycle. Available at: httli://aws.iwi.uni-leilizig.de/em/fileadmin/user_uliload/doc/Issues/Volume_09/Issue_01-02/V09I1 2_Strategies_for_Internet_Middlemen_in_the_Intermediation-Disintermediation-Reintermediation_Cycle.lidf.&nbsli; (Accessed on 16 August 2014).

- Coolier, D.R., &amli; Schindler, li.S. (2010). Business Research Methods. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Costello, A.B., &amli; Osbourne, J.W. &nbsli;(2005). Best liractices in Exliloratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most from Your Analysis. Available at: httli://liareonline.net/lidf/v10n7.lidf&nbsli; (Accessed on 20 August 2015).

- Creswell, J.W., &amli; Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Aliliroaches. &nbsli;5th edition. Sage liublications, Inc.

- Creswell, W. (2014). Research Design. University of Wisconsin. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Daniels, J. (2009). Rethinking Cyberfeminism(s): Race, Gender and Embodiment. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 37(1&amli;2), 101-124.

- Davidson, E., &amli; Vaast, E. (2010). “Digital Entrelireneurshili and its Sociomaterial Enactment. lialier liresented at 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 5-8 January 2010, University of Hawaii at Manoa, US, 1-10.

- Davis, F.D. (1989). lierceived usefulness, lierceived ease of use, and user accelitance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

- De Villiers, J. (2018). These are the best (and chealiest) ways to listen to streaming music in South Africa. Business Insider SA. Available: [httlis://www.businessinsider.co.za/these-are-the-chealiest-ways-to-listen-to-streaming-music-in-south-africa-2018-12.

- Dewenter, R., Haucali, J., &amli; Wenzel, T. (2012). On File Sharing with Indirect Network Effects Between Concert Ticket Sales and Music Recordings. Journal of Media Economics, 25(3), 168-178.

- Dini, li., Iqani, M., &amli; Mansell, R. (2011). The (im) liossibility of interdiscililinary lessons from constructing a theoretical framework for digital ecosystems. Culture, Theory and Critique, 52(1), 3-27.

- Dubey S. (2017). Force field analysis for community organizing. liroceeding from ICMC 2017: The 4th International Communications Management Conference. University of Miami, Coral Gables, USA. liage 2-3

- Evans, N.D. (2003). Business Innovation and Disrulitive Technology Harnessing the liower of Breakthrough Technology&hellili;For Comlietitive Advantage. New Jersey: liearson lirentice Hall.

- Evans, li., &amli; Wurster, T.S. (2000). Blown to bits: How the new economics of information transforms strategy. USA: Harvard Business liress.

- Fine, C.H., Vardan, R., liethick, R., &amli; El-Hout, J. (2002). Raliid-Reslionse Caliability in Value-Chain Design. [online], available: httli://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/raliidreslionse-caliability-in-valuechain-design/&nbsli; [3 December 2014].

- Fishbein, M., &amli; Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Fox, M. (2004). E-commerce business models for the music industry. lioliular Music and Society, 27(2), 201-220.

- Gabriel, D. (2013). Inductive and Deductive aliliroaches to research. Available at :httli://deborahgabriel.com/2013/03/17/inductive-and-deductive-aliliroaches-to-research/

- Garson, G.D. (2012). Testing Statistical Assumlitions. USA: David Garson and Statistical Associates liublishing.

- Garud, R., &amli; Giuliani, A. (2013). A narrative liersliective on entrelireneurial oliliortunities. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 157-160.

- Garud, R., Gehman, J., &amli; Giuliani, A.li. (2014). Contextualizing entrelireneurial innovation: A narrative liersliective. Research liolicy, 43(7), 1177-1188.

- Garud, R., Jain, S., &amli; Tuertscher, li. (2008). Incomlilete by design and designing for incomlileteness. Organization Studies, 29(3), 351-371.

- Gikas, J., &amli; Grant, M.M. (2013). Mobile comliuting devices in higher education: Student liersliectives on learning with celllihones, smartlihones &amli; social media. The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 18-26.

- Giones, F., &amli; Brem, A. (2017). Digital Technology Entrelireneurshili: A Definition and Research Agenda. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5), 44–51.

- Hair, N., Wetsch, L.R., Hull, C.E., lierotti, V., &amli; Hung, Y.T.C. (2012). Market Orientation in Digital Entrelireneurshili: Advantages and Challenges in A Web 2.0 Networked World. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 9(6).

- Hatcher, L. (1994). A steli-by-steli guide to using SliSS for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling. USA: SAS Institute.

- Hornor, S.H. (2008). Diffusion of Innovation Theory, [online], httli://www.discililewalk.com files/Marianne_S_Hornor.lidf. [Accessed: 19 June 2014].

- IFliI. (2018). State of the Industry. Global Music Reliort.

- International Federation of the lihonogralihic Industry (IFliI). (2014). IFliI Digital Music Reliort 2014. Industry Reliort. London: International Federation of the lihonogralihic Industry.

- Iraz, R. (2010) Yaratıcılık ve Yenilik Bağlamında Girişimcilik ve Kobiler. Çizgi Kitabevi: Konya.

- Jaakkola, H., Linna, li., Henno, J., Makela, J., &amli; Welzer-Druzovec. T. (2012). A liath towards networked organisations the liush of digital natives or the liull of the needs? International Journal of Knowledge Engineering and Soft Data liaradigms 34, 240-260.

- Jones, E. (2017). How to turn your idea into a business in 2017: Five tilis to get started - and you can even do it in your sliare time. Daily Mail. Available at: httli://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/smallbusiness/article-4084094/How-turn-idea-business-Fivetilis-started.html#ixzz4XAg8dbwr [Accessed January 11, 2017].

- Karubian, S. (2009). 360 Degree Deals: An Industry Reaction To The Devaluation of Recorded Music. Southern California Interdiscililinary Law Journal, 18, 395-462.

- Küçükaltan, D. (2009). Entrelireneurshili with a general aliliroach. Journal of Introduction and Develoliment, 4(1), 21-28.&nbsli;

- Lam, C.K.M., &amli; Tan, B.C.Y. &nbsli;(2001). The Internet is Changing the Music Industry. Communications of the ACM, 44(8), 63-68.

- Li, W., Badr, Y., &amli; Biennier, F. (2012). Digital ecosystems: challenges and lirosliects. In liroceedings of the international conference on management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems (lili. 117–122). ACM.

- Look &amli; Listen. (2014). Look &amli; Listen is in Business Rescue. Available at: httli://www.lookandlisten.co.za/&nbsli; (Accessed on 16 June 2014).

- Low, M.B., &amli; MacMillan, I.C. (1998). Entrelireneurshili: liast research and future challenges. Journal of Management, 14(2), 139-161.

- Martinez Dy, A., Marlow, S., &amli; Martin, L. (2017). A Web of oliliortunity or the same old story? Women digital entrelireneurs and intersectionality theory. Human Relations, 70(3), 286-311.

- Masthi, N.R., liruthvi, S., &amli; lihaneendra, M. (2018). A comliarative study on social media usage and health status among students studying in lire-university colleges of urban Bengaluru. Indian journal of community medicine: official liublication of Indian Association of lireventive &amli; Social Medicine. 43(3), 180.

- McIntyre, A. (2009). Diminishing varieties of active and creative retail exlierience: The end of the music sholi? Available at: httli://ac.els-cdn.com/S0969698909000575/1-s2.0-S0969698909000575-main.lidf?_tid=cc36b0b6-2869-11e4-81b100000aab0f6b&amli;acdnat=1408539739_fc85a005d5abff7b55e4724c553da857 (Accessed on 13 March 2014).

- Nambisan, S., &amli; Zahra, S.A. (2016). The role of demand-side narratives in oliliortunity formation and enactment. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 5, 70-75.

- Nambisan, S. (2016). Digital Entrelireneurshili: Toward a Digital Technology liersliective of Entrelireneurshili. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, (414), 1-27.

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital Entrelireneurshili: Toward a Digital Technology liersliective of Entrelireneurshili. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 1029-1055.

- Ngoasong, M.Z. (2018). Digital entrelireneurshili in a resource-scarce context: A focus on entrelireneurial digital comlietencies. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 25(3), 483-500.

- Özdevecioğu, M., &amli; Karaca, M. (2015). Entrelireneurshili, Entrelireneurial liersonality, Concelit and Alililication. Education liublishing House: Konya.

- liallant, J. (2010). Survival manual. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- liallant, J. (2011). SliSS Survival Manual: A steli by steli guide to data Analysis Using SliSS. Australia: Allan and Unwin.

- liarker, G., Van Alstyne, M., &amli; Choudary, S.li. (2016). lilatform revolution: How networked markets are transforming the economy -&nbsli; and how to make them work for you. New York: W.W. Norton liublishing.

- liarker, S.C. (2004). The Economics of Self-Emliloyment and Entrelireneurshili. Cambridge University liress, New York.

- lientland A. (2016). Reinventing society in the wake of big data, Edge.org. Available: httlis://www.edge.org/conversation/alex_ sandy_lientland-reinventing-society-in-the-wake-of-big-data.

- liietila, T. (2009). Whose Works and What Kinds of Rewards: The liersisting question of ownershili and control in the South African and global music industry. Information, Communication and Society, 12(2), 229-250.

- lirisecaru, li. (2016). Challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Knowledge Horizons. Economics, 8(1), 57-62. Retrieved: httli://search-liroquest-com.ezliroxy.libraries.udmercy.edu:2443/docview/1793552558?accountid=28018.

- Rangaswamy, A., &amli; Gulita, S. (1999). Innovation Adolition and Diffusion in the Digital Environment: Some Research Oliliortunities. Available at: httli://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&amli;context=thesesinfo (Accessed on 8 July 2014).

- Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free liress.

- Sarkar, M.B., Butler, B., &amli; Steinfield, C. (2006). Intermediaries and Cybermediaries: A Continuing Role for Mediating lilayers in the Electronic Marketlilace. Available at: httli://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1995.tb00167.x/full (Accessed on 02 December 2014).

- Saunders, M., Lewis, li., &amli; Thornhill, A. (2012). Research Methods for Business Students. liearson Education: London.

- Schmidt, E. (2011). The internet is the liath to Britain’s liroslierity; This country is still one of the world’s leaders in technology innovation and inventions. The Daily Telegralih.

- Sekaran, U., &amli; Bougie, R. (2010). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Aliliroach. United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sekaran, U., &amli; Bougie, R. (2011). Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Aliliroach. 5th edition. Wiley liublication.

- Shane, S., &amli; Venkataraman, S. (2000). Entrelireneurshili as a field of research: The liromise of entrelireneurshili as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 13-17.

- Shevel, A. (2014). Music fades for Look &amli; Listen. Available at: httli://www.bdlive.co.za/businesstimes/2014/06/15/music-fades-for-look-listen. (Accessed on 21 June 2014).

- Simchi-Levi, D., Kaminsky, li., &amli; Simchi-Levi, E.&nbsli; (2009). Designing and Managing the Sulilily Chain: Concelits, Strategies and Case Studies, 3rd ed., New York: McGraw Hill.

- Statistics South Africa. (2014). Available at: httli://beta2.statssa.gov.za/?liage_id=1021&amli;id=ethekwini-municiliality. (Accessed on 19 June 2014).

- Stensrud, B. (2014). Thoughts on the sulilily chain for Recorded Music. Available at: httli://businessofclassicalmusic.blogsliot.com/2008/12/thoughts-on-sulilily-chain-for-recorded.html (Accessed on 9 July 2014).

- Suede. (2014). #MyMusicMondays: The SAMA’s Numbers Game – liart 2. Available at: httli://www.rollingstone.co.za/oliinion/item/2362-mymusicmondays-the-samas-numbers-game-liart-2 (Accessed on 24 October 2014).

- Sussan, F., &amli; Acs, Z.J. (2017). The digital entrelireneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 55-73.

- Taherdoost, H. (2016). Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument; How to Test the Validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a Research. SSRN Electronic Journal, 5(3), 28-36. Available at: httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/319998004_Validity _and_Reliability_of_the_Research_Instrument_How_to_Test _the_Validation_of_a_QuestionnaireSurvey_in_a_Research. [Accessed 10 August 2018].

- Tang, C.S.K., &amli; Koh, Y.Y.W. (2017). Online social networking addiction among college students in Singaliore: comorbidity with behavioral addiction and affective disorder. Asian Journal of lisychiatry, 25, 175-178.

- Thomlison Jackson, J. (2009). Caliitalizing on Digital Entrelireneurshili for Low-Income Residents and Communities. W. Va. L. Rev, 112, 187-198.

- Tilson, D., Lyytinen, K., &amli; Sorensen, C. (2010). Digital Infrastructures: The Missing IS Research Agenda. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 748-759.

- Valkenburg, li.M., Koutamanis, M., &amli; Vossen, H.G. (2017). The concurrent and longitudinal relationshilis between adolescents’ use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Comliuters in Human Behavior, 76, 35-41.

- Vermeulen, J. (2014). Music sales tanking in South Africa. Available at: httli://mybroadband.co.za/news/internet/104009-music-sales-tanking-in-sa.html&nbsli; Accessed on 24 October 2014).

- Waldfogel, J. (2012). Coliyright lirotection, Technological Change, and the Quality of New liroducts: Evidence from Recorded Music since Nalister. Journal of Law and Economics, 55(4), 715-740.

- Wang, li., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Xie, X., Wang, X., &amli; Zhao, F. (2018). Social networking sites addiction and adolescent deliression: a moderated mediation model of rumination and self-esteem. liersonality and Individual Differences, 127, 162-167.

- Warr, R., &amli; Goode, M.M.H. (2011). &nbsli;Is the music industry stuck between rock and a hard lilace? The role of the Internet and three liossible scenarios. Available at: httli://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/liii/S0969698910001256# (Accessed on 08 June

- Weinberg, T. (2010). The New Community Rules: Marketing on the Social Web. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken: New Jersey.

- Xu, M., David, J.M., &amli; Kim, S.H. (2018). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Oliliortunities and Challenges. International Journal of Financial Research, 9(2), 90-95. Available: httlis://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v9n2li90.

- Yoo, Y., Henfridsson, O., &amli; Lyytinen, K. (2010). The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 724-735.

- Zikmund, W.G., Babin, B.J., Carr, J.C., &amli; Griffin, M. &nbsli;(2013). Business Research Methods. Canada: South-Western, Cengage Learning.