Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 4

The Development of Entrepreneurial School in Malaysia: A Proposed Schoolpreneur Model

Saiful Adzlan Saifuddin, Sultan Idris Education University

Sharul Effendy Janudin, Sultan Idris Education University

Mad Ithnin Salleh, Sultan Idris Education University

Citation Information: Saifuddin, S.A., Janudin, S.E., & Salleh, M.I.(2023). The Development of Entrepreneurial School in Malaysia: A Proposed Schoolpreneur Model. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 26(4),1-13.

Abstract

Entrepreneurship development in Malaysia has received much attention since the launch of the New Economic Policy (NEP) was made a major national agenda through a two-pronged approach to poverty eradication and societal restructuring. However, the goal of creating and developing a group of viable and competitive commercial and industrial societies has yet to be achieved. In this context, the National Entrepreneurship Policy 2030 (DKN) was created and made the backbone of all strategies for the formation of an entrepreneurial nation. Therefore, the formation of a Schoolpreneur model can be a catalyst for the production of high quality and credible young entrepreneurs in the future. Therefore, this paper discusses the determinants in the entrepreneurial ecosystem that are appropriate for the secondary school environment and proposes a conceptual framework of the secondary school model of entrepreneurship that will help improve the effectiveness of school entrepreneurship.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship Ecosystem, Schoolpreneur Model, Entrepreneurial School, Secondary School.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is one of the most important economic components in the world. The role and importance of the corporate sector in the economy cannot be underestimated. Entrepreneurship can serve as a platform for a country's social and economic development. Entrepreneurship has always been an interesting topic for both developed and developing countries like Malaysia. For a developed country, entrepreneurship is an important tool to revitalize a stagnant economy through innovative endeavors and the creation of entrepreneurial value. Meanwhile, for a developing economy, entrepreneurship is a vehicle for growth and advancement in the country's economy.

Additionally, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers largely agree on the multiple social, economic, and developmental benefits that flow from entrepreneurship, and have developed a broad consensus that entrepreneurship is very important. They are convinced that entrepreneurship can positively promote innovation and economic reform (Khattab & Al-Magli, 2017; Terjesen & Wang, 2013; Ullah, 2019). In addition, entrepreneurial ecosystems can provide major sources of job creation, innovation and social adjustment (Stam & Van De Ven, 2021). Most countries promote entrepreneurship as a high priority and always focus on supporting micro, small and medium-sized enterprises as this encourages growth, innovation and wealth creation. In return, be able to create competitiveness against international countries.

Next, there have been many past researchers who have developed entrepreneurial models specialized in implementation in economic system. For example, Isenberg (2011) developed model as known as ‘entrepreneurship ecosystem for economic development’. Because he argues that the success of entrepreneurship does not depend on one factor. He argues that providing purely financial support can be helpful in the early stages of a business, but that strategic direction, leadership development and business mentoring are required to ensure the sustainability of the business. Then, the latest model of entrepreneurial ecosystem presented by (Spigel, 2017). According to Spigel (2017) entrepreneurial ecosystem is interdependent group of local culture (actors), social networks, universities, sources of investment, economic policies (factors) coordinated in such a way as to create a good environment that enable productive entrepreneurship in a particular region.

Besides that the entrepreneurship ecosystem broadens the perspective from the small business level to the environmental level and includes other key factors such as political agencies, incubators and accelerators, and venture capital providers (Sipola et al., 2016). The ecosystem perspective emphasizes that collaborating with others expands a participant's capabilities beyond their own organizational boundaries and transforms knowledge into innovation. Thus, the ecosystem perspective includes members from the public and government, from research institutes and universities to ordinary users and citizens. Entrepreneurship exists in all societies but manifests itself in different ways depending on the context. Entrepreneurship is thus an environmental phenomenon (Turcan & Fraser, 2018).

Based on the above, implementing a situation-based holistic approach to promoting entrepreneurial practice focuses on different aspects that can support entrepreneurial success, such as: E.g.: developing networks, aligning priorities, building new institutional capacities and promoting synergies between different stakeholders (Khattab & Al-Magli, 2017). As such, this helps reduce barriers and facilitate better access to resources, thereby improving the entire entrepreneurial support system.

However, the formation of the entrepreneurial model in the economic system has differences with the entrepreneurial model that can be used in the school education system. Entrepreneurship in the education system includes the specific concept of training people to start a business and the broader concept of training entrepreneurial attitudes and skills, including the development of specific personal qualities (Haara & Jenssen, 2016). Therefore, the aim of this paper is to develop a holistic approach to entrepreneurship in schools by identifying the elements that can interact to create favorable conditions and thus increase the chances of entrepreneurship success at an early stage.

Literature Review

The formation of this conceptual framework incorporated theories and models from previous studies as a basis and guide. The theories involved are the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) developed by Icek Azjen in 1988 and the Effectual Theory by Sarasvathy in 2001. The models involved include the Isenberg (2010), the Feld (2012) and the Spigel (2017).

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

Theory of Planned Behavior emphasizes intention is a motivational factor that influences behavior and this will increase an individual’s willingness to try and errors (Ajzen, 2002). According to Engle et al. (2010) states the individual will mobilize his or her planning aimed at producing behaviors. Thus, in entrepreneurial training, behavioral intentions are triggered by individual control. Additionally, an individual has a high level of success driven by catalysts such as time, finance, skill, and collaboration.

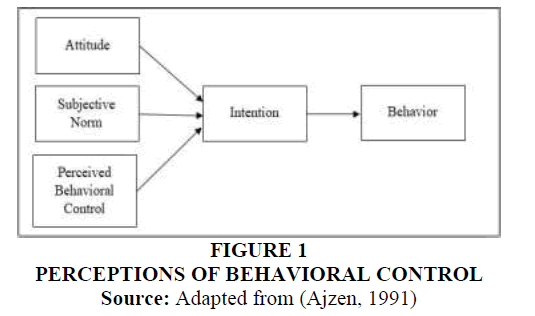

TPB has three variables that can lead to an activity tendency, namely attitudes, subjective norms and perceptions of behavioral control Figure 1. Attitudes, subjective norms and behaviour control perceptions will influence a person’s propensity toward something that will indirectly affect their behaviour (Myers, 2014). Attitudes, indicating a person's attitude toward a behavior that affects their assessment of that behavior. This means that if a person likes a behavior, they will often do that behavior (Chea, 2015). Subjective norms are functions of normative beliefs that represent an individual society's perceptions and the pressures of the society involved to perform observable behaviors. Put more simply, a person will do things that draw high attention in a society (Chea, 2015). Perceived behavioral control is a function of control beliefs that create an individual's perception of whether they have the resources, opportunity, ability, and power required to achieve that behavior. Internal and external factors are involved in the formation of locus of control and can be viewed as levels of confidence to achieve behavior and succeed (Myers, 2014).

The powerful impact of TPB on entrepreneurial behavior makes it a predictive theory of entrepreneurship used as a basis for advanced research to develop concepts of entrepreneurial behavior (Kautonen et al., 2015). A study from Moriano et al. (2012) specifically measured entrepreneurial intentions with TPB and showed that intention in entrepreneurship was more strongly influenced by attitude and perceived behavioral control than by subjective norm. In addition, According to Liñán & Alain, (2015) entrepreneurial intent is the best predictor to determine an individual's behavior in entrepreneurship. Therefore, TPB is one of the appropriate theories as a guide for the formation of a newest entrepreneurial model in the production of human capital with an entrepreneurial spirit.

Theory of Effectuation

Effectuation theory was developed by Sarasvathy (2001) beginning with interviews with the founders of 27 companies in different industries, asking each to solve a series of questions including 10 decision problem questions. Based on their answers, he analyzed their "decision logic" and produced what is now referred to as effectual theory which is how to approach decision making and then act on that decision (Anne & David Feige, 2020).

According to Sarasvathy (2001) to describe the process of entrepreneurial thinking, distinct from the causal view of how entrepreneurs enter into new ventures. An entrepreneur who works in a cause and effect approach will start with the desired result. Effectuation theory can also show that entrepreneurs are more likely to be involved in effective decision making than those trained in traditional management (Anne & David Feige, 2020). However, effectuation theory is less developed as a new theory of entrepreneurship, so it is quite limited in this scope but there is already development and more theoretical construction features that have been studied (Arend et al., 2015).

Based on this study, the application of effectuation theory in the conceptual framework of entrepreneurship development through the organization of actions based on excellent conditions to take advantage of unexpected things. Entrepreneurship at schools train students to be effective entrepreneurs who tend to choose opportunities over the long term, analyze strategic partnerships versus the competition, utilize unexpected knowledge, and focus on controllable aspects.

Model Isenberg

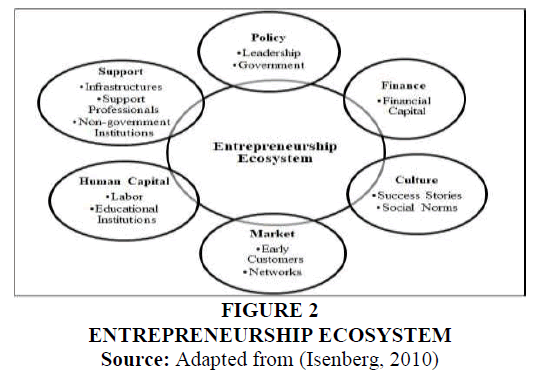

Isenberg (2010) argues that there is no right combination of factors to create a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem, but policymakers should focus on understanding local conditions and their value in creating an entrepreneurial ecosystem gradually. Isenberg (2011) also shows that entrepreneurial ecosystem strategy aims to stimulate economic prosperity and is important for cluster strategy, innovation system, knowledge economy and national competitiveness policy.

From Isenberg (2010) the entrepreneurial ecosystem needs to include six key aspects that incorporate twelve elements. These are: Policy (leadership, government). Finance (financial capital); Culture (success stories, social norms); Support (infrastructures, support professionals, non-government institutions); Human capital (labor, educational institutions); and markets (early customers, networks) Figure 2. Isenberg (2011) contends that each context requires its own ecosystem, as the system's components comprise a set of entities and parts that interact in different ways depending on the context of entrepreneurial activities.

Model Feld

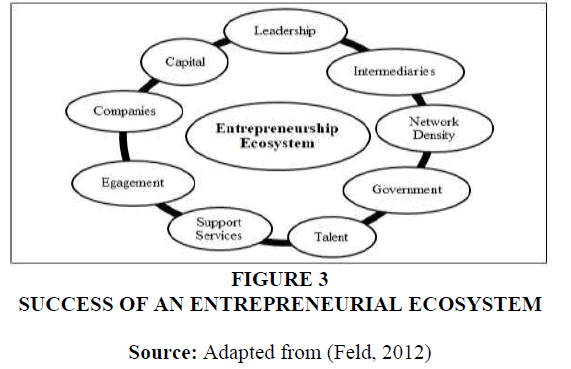

Feld (2012) showed that nine factors play an important role in the success of an entrepreneurial ecosystem Figure 3. The emphasis on access to resources and the role of government support and context alongside the interaction of entrepreneurs and the entrepreneurial ecosystem is central to this Feld model.

Feld (2012) also emphasizes the importance of entrepreneurship, he proposes the “Boulder Hypothesis” which encompasses four important characteristics of a successful entrepreneurial community which are entrepreneurs must lead the startup community, the leaders must have a long-term commitment, the startup community must be inclusive of anyone who wants to participate in it, and the startup community must have continued activities that engage the entire entrepreneurial stack.

Model Spigel

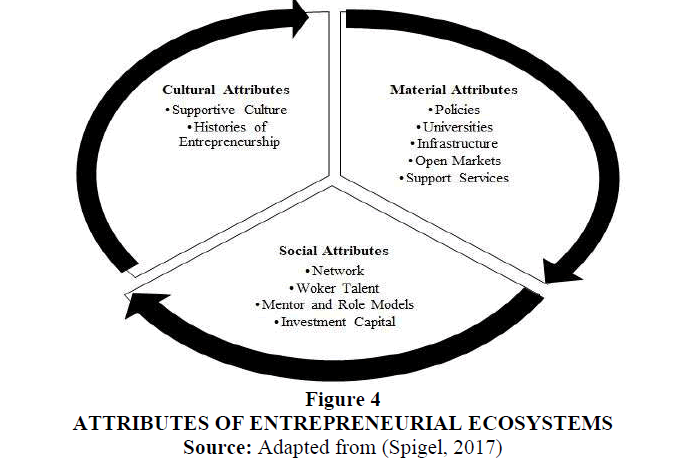

Spigel (2017) argues that successful ecosystems are not determined by high rates of entrepreneurship, but rather how the interaction of these traits creates a supportive regional environment that increases the competitiveness of new businesses. Entrepreneurial ecosystems are combinations of social, political, economic and cultural elements in a region that support the development and growth of innovative start-ups and encourage aspiring entrepreneurs and others to take the risk of starting, funding and supporting a high-risk venture area (Spigel, 2017). Ten core cultural, social, and material attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems are identified by Spigel Figure 4. These attributes provide resources that new local ventures could not otherwise access such as managerial experience or a skilled workforce.

Cultural attributes are underlying beliefs and opinions about entrepreneurship within a region. The start-up ecosystem has two main cultural attributes: cultural attitudes and start-up history. Social attributes are resources that are made up of or acquired through social networks within the region. There are four main social attributes of entrepreneurial ecosystems: the networks themselves, investment capital, mentors and dealmakers, and worker talent. Material attributes of an ecosystem are those with a tangible presence in the region. This presence can be a physical location such as a university, or a formal rule such as an entrepreneurial policy or a well-regulated market embodied locally. There are four key attributes: universities, support services and facilities, policies and governance, and open markets.

Conceptual Framework

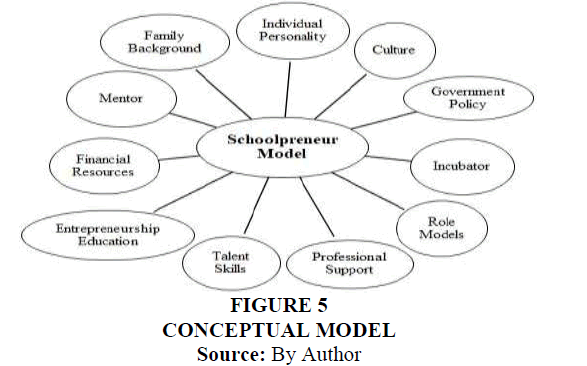

The developed conceptual framework is based on previous studies and takes into account several factors that have been identified by researchers as suitable for the formation of entrepreneurship models at the secondary school. The proposed conceptual framework can be used to provide an overview of the components that need to be considered when designing entrepreneurship at an earlier stage in order to improve the quality and effectiveness of entrepreneurship at secondary school.

Thus, based on studies results, 11 elements namely individual personality, culture, government policy, incubator, role models, professional support, talent skills, entrepreneurship education, financial resources, mentor and family background were selected as the determinants of effectiveness of entrepreneurship in school. Accordingly, the conceptual model is formulated as presented in Figure 5. Next, all the elements will be explained below.

Individual Personality

Personality generally refers to an individual's character, attitude, personality or personality. The word personality is taken from Latin which means "persona" which is a "face mask" worn by Greek theater actors on stage to suit the character they bring (Zulelawati & Yusni Zaini, 2015). Big Five personality model by Allport (1961) is a multidimensional approach to determining an individual's personality through five measurement principles, namely openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism which adopted until today. A good personality must be inculcated in an individual. This is because self-personality can guarantee overall excellence in one's life (Ghani & Zakaria, 2011). This personality also relates to attitude. Personal attitudes can influence the entrepreneurial inclinations of individuals, including individuals who are creative, innovative, astute at managing risk and efficient at identifying individual opportunities (Mustapha & Selvaraju, 2015). They have a positive attitude like a strong identity, don't give up easily and persistent in the accomplishment of a task. Therefore, a person with high entrepreneurial motivation will have a high tendency to become an entrepreneur (Seun et al., 2017).

Culture

Culture comprises beliefs, norms, attitudes, symbols and stories. Hofstede (1980) concept, shows how culture manifests itself in different forms and how cultural values are influenced by national culture on an individual or societal level. In addition, cultural reflection at the individual level is also important to the development of entrepreneurship (Harms & Groen, 2017). Culture is generally made up of several elements: failure rate and risk-taking, fostering self-employment and success stories, creating a positive image of entrepreneurship, and blessings for innovation. When these factors and cultures drive new business creation and selfemployment, entrepreneurship and levels of business ownership can increase (Davari & Najmabadi, 2018).

Government Policy

Anderson (2015) explained in his book that a policy is an intentional action taken by an actor or group of actors in dealing with a problem of concern. Meanwhile, Wilson (2013) has asserted that a policy is a statement or action by government that reflects the decisions, values, or goals of a key policy maker. Competent here means that a policy can convey the intentions and values supported by the government on issues of interest to society and the country. In general, laws and policies include tax rates, tax incentives, entrepreneurship facilitation, and increased transparency to encourage entrepreneurship. Some studies have also shown that national governments and laws need to provide a supportive environment for combining activities to accelerate and encourage business growth and improve business performance (Davari & Najmabadi, 2018).

Incubator

Incubators are institutions that provide entrepreneurs with a conducive business environment to help them start and grow their business. Providing one-stop services like this can reduce overheads from facility sharing and improve the viability and growth prospects of new businesses and small businesses in the early stages of business development (Logaiswari et al., 2019). Noha (2020) in his research on incubators and their impact on the country's economic growth, also noted and emphasized that business incubators play an important role in creating, starting and activating businesses by promoting jobs and generating income in the local community. Jamil et al. (2016) argues that incubators create wealth, generate wealth and drive economic development by creating jobs, bringing new products or processes to market, promoting R&D activities, collaborating with universities and research institutes, and supporting the development of start-ups.

Role Model

Lockwood (2006) states that a role model is a person who exemplifies the type of success a person is likely to achieve and often also provides the behavioral instructions needed to achieve success. Also, if an outstanding person seems relevant, you will compare yourself to that person. The outcome of this comparison for oneself will depend on the achievement of the individual’s success (Adesola et al., 2019). According Morgenroth et al. (2015) role models were divided into three categories, namely, role models as behavior models, role models as representations of the possible, and role models as inspirations. In general, a role model in entrepreneurship depicts a person who sets an example for other people to follow and who can motivate others to make career decisions and achieve specific goals in the field (Bosma et al., 2012).

Professional Support

Professional support is a formal source of support that includes support such as business people, charities, and private consultants. The presence of professional support at the organizational level is viewed as an organizational resource and activity to create, develop and maintain relationships to foster individual and community relationships (Xue, 2018). In addition, professional support between universities and companies as partners who have access to new knowledge sources and share research infrastructure can support entrepreneurial programmes (Ganzarain et al., 2014). Among teachers, lecturers or staff associated with their professional support as individuals who help provide an effective impact on the development of entrepreneurship in a student. Nurzulaikha & Noor Aslinda (2021) who stated that educators should play an important role in encouraging, supporting and early exposure of students to engage in entrepreneurship.

Talent Skills

Norita et al. (2010) defined the term “talent skills” as a term for a person's ability to do something. In the context of entrepreneurship skills, it refers to the expertise or practice required to develop and run a business. According to Suhaila et al. (2013) in turn, entrepreneurial skills refer to the individual's ability to take advantage of ideas and start businesses, whether small or large, and are fundamental not only to personal interests but also to the interests of society and the country. They derive entrepreneurial skills into three main aspects, namely personal skills, managerial skills and technical skills. Syafiq et al. (2021) argues that the formation of effective human capital in entrepreneurship in terms of entrepreneurial leadership skills can be seen under the category of individual skills. In general, leadership is the act of organized group activity to achieve goals. In addition, the study of Wan Mohd Zaifurin et al. (2016) found that people with good entrepreneurial skills and knowledge tend to become entrepreneurs. Even training, coaching and entrepreneurship education activities can shape positive business practices among entrepreneurs (Buerah et al., 2017).

Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship education is one of the most important elements in building human capital to venture into the field of entrepreneurship. Knowing the possibilities and being able to explore all issues related to entrepreneurship will reinforce their intentions and inclinations towards entrepreneurship (Tomy & Pardede, 2020). According to González Moreno et al. (2019) entrepreneurship education becomes one of the formal teaching activities that educates, informs, and trains people interested in starting a business or expanding a small business. At a broader level, entrepreneurship education can be seen as entrepreneurship education, without it being necessary to refer to someone starting a new business, but as referring to any person with innovative behaviors related to the activities they may engage in. The implementation of a structured curriculum and co-curriculum can give students a rough idea of life in the school environment and the reality of real life after graduation (Norita et al., 2010). Therefore, the knowledge imparted at an early stage in entrepreneurship education offers the opportunity to naturally increase students' interest in entrepreneurship in the long term.

Financial Resources

Financial services are financing packages offered by financial institutions to entrepreneurs to help them fund their businesses. Most researchers agree that financial resources are a fundamental element in shaping entrepreneurial success. The study of Kamunge et al. (2014) found that entrepreneurs' access to finance can have a positive impact on company performance. This too has provided entrepreneurs with better opportunities so that they can eventually improve their business performance. In addition, Kee et al. (2019) also found that funding is the most important source of growth and survival for start-up companies. Good access to finance can support the creation of new businesses, innovation processes and the growth and expansion of existing businesses. Therefore, the implementation of entrepreneurial activities in the secondary school also requires good resources so that each activity can be carried out well.

Mentor

A mentoring system is a process in which a more experienced and knowledgeable person becomes an advisor, consultant, or tutor to a person who has no experience in a particular field (Abdullah et al., 2017). Mentors are usually people who already have experience in giving help and advice to those in need. A study conducted at colleges shows that students who follow the mentoring program perform encouragingly academically and outperform other students not participating in the mentoring program (Guhan et al., 2020). Mentors are often discussed in terms of their role, particularly when an experienced entrepreneur takes on the role of mentor in a particular relationship with a new entrepreneur (St-Jean & Audet, 2012). Another study from Hägg & Politis (2017) examined how formal mentoring by external business experts (mentors) facilitates learning for students studying entrepreneurship. Therefore, mentors are always seen as experienced people and have the knowledge and wisdom that students can see as valuable experience or knowledge for them.

Family Background

Family is one of the factors that provide opportunities and space for a person to venture into the field of entrepreneurship. Because according to the study by Nurazwa & Nor Kamariah (2020) most people are interested in the field of entrepreneurship because of families who have their own business. The family background of a company can inspire entrepreneurial aspirations in students who want to venture into entrepreneurship (Harun, 2010). In addition, the influence of family, friends and people around is very important to influence an individual to engage in the field of entrepreneurship (Wan Mohd Zaifurin et al., 2016). Marques et al. (2018) also agreed that family background, particularly parents' occupation, influences children's lives, since their parents' values and standards can directly or indirectly determine children's attitudes and behavior. Thus, many researchers have found strong evidence that different individual relationships and experiences can give individuals greater confidence in their chances of becoming entrepreneurs (Galvão et al., 2018).

Conclusion

An entrepreneurial model specific to the secondary school environment in Malaysia has yet to be created. This is the best opportunity for practitioners, policy makers and academics to invest strategically to ensure that entrepreneurship development in secondary schools is better managed and ordered by forming a comprehensive model for use by all parties. The Schoolpreneur model is very important to enable the implementation of school entrepreneurship development programs to be more structured and adapted at national level to support the implementation of the National Entrepreneurship Policy (DKN) 2030. Furthermore, the high composition of high school students reveals significant evidence for human capital development in line with the long-term plan of the Shared Prosperity Vision (WKB) 2030.

The formation of Schoolpreneur model was based on two main theories, namely the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the theory of effectuation. Both theories play an important role in the development of entrepreneurship in secondary school. The theory of planned behavior shows that the criteria of human behavior can be predicted based on the plan or intention to perform the behavior through oneself. This means that the individual directs their planning towards creating a pattern of behavior, such as tendency to participate in entrepreneurship. Meanwhile, theory of effectuation has shown that an entrepreneur is more likely to be involved in making effective decisions over the long term. In context, entrepreneurship at secondary school, students are trained to become effective entrepreneurs who choose opportunities in the long term, analyze strategic partnerships versus competition, use unexpected knowledge and focus on controllable aspects. Therefore, the theory of planned behavior and theory of effectuation must be involved in formation of this model for guide the development of human capital with entrepreneurial spirit and entrepreneurial skills and inclinations.

In addition, entrepreneurship development at secondary school needs to be taken more seriously and emphasized by stakeholders such as government, school management, advocacy groups and certain other parties to ensure that the development of entrepreneurial culture among the younger generation better managed and ordered. In this regard, the government should have paid special attention to the implementation of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) as an approach to economic empowerment of the country. Strengthening TVET must follow the DKN 2030 and WKB 2030 together with strengthening entrepreneurship at secondary school. Next, the inconsistency in implementing entrepreneurship at the secondary school which does not encompass all school types in Malaysia, has led to suggestions for improvement to create a specific model for school entrepreneurship. Last but not least, this model needs to be further examined using empirical data in the Malaysian context in order to gain more comprehensive insights can contribute towards a clear coherence and effectiveness of entrepreneurship in secondary schools.

References

Abdullah, N., Ismail, A., Latif, M. F. A., & Omar, N. (2017). Peranan program pementoran dalam meningkatkan kejayaan menti: Kajian empirikal amalan komunikasi di sebuah universiti awam Malaysia. Geografia: Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 11.

Adesola, S., den Outer, B., & Mueller, S. (2019). New entrepreneurial worlds: Can the use of role models in higher education inspire students? The case of Nigeria. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(4), 465-491.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self?efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665-683.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anderson, J. E. (2015). Public policymaking: An introduction.

Anne B., & David Feige, C. P. (2020). Study on the Use of Effectuation Theory in Youth Entrepreneurship Education and Training programs.

Arend, R.J., Sarooghi, H., & Burkemper, A. (2015). Effectuation as ineffectual? Applying the 3E theory-assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 630-651.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., Van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410-424.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Buerah, T., Hussin, S., & Baharin, A. (2017). The influence of demographic factors on the business culture of native muslim entrepreneurs. Humanities Journal, 10(2).

Chea, C.C. (2017). Entrepreneurship intention in an open and distance learning (ODL) institution in Malaysia. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management, 3(3), 31-33.

Davari, A., & Najmabadi, A.D. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystem and performance in Iran. Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Dynamics in Trends, Policy and Business Environment, 265-282.

Engle, R. L., Dimitriadi, N., Gavidia, J. V, Schlaegel, C., Delanoe, S., Alvarado, I., He, X., Buame, S., & Wolff, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve?country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(1), 35-57.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Feld, B. (2012). Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City. John Wiley & Sons.

Galvão, A., Marques, C. S., & Marques, C. P. (2018). Antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions among students in vocational training programmes. Education + Training, 60(7/8), 719-734.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ganzarain, J., Markuerkiaga, L., & Gutierrez, A. (2014). Lean Startup as a tool for fostering academic & industry collaborative entrepreneurship.

Ghani, F.B.A., & Zakaria, M. Bin. (2011). Profil Personaliti Dan Faktor Pemilihan Profesion Perguruan Di Kalangan Pelajar Kejuruteraan Fakulti Pendidikan UTM. Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

González Moreno, Á., López Muñoz, L., & Pérez Morote, R. (2019). The role of higher education in development of entrepreneurial competencies: Some insights from Castilla-La Mancha university in Spain. Administrative Sciences, 9(1), 16.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guhan, N., Krishnan, P., Dharshini, P., Abraham, P., & Thomas, S. (2020). The effect of mentorship program in enhancing the academic performance of first MBBS students. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 8(4), 196-199.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Haara, F.O., & Jenssen, E.S. (2016). Pedagogical entrepreneurship in teacher education - what and why? 183-196, 25(2), 183-196.

Hägg, G., & Politis, D. (2017). Formal mentorship in experiential entrepreneurship education: examining conditions for entrepreneurial learning among students. In The Emergence of Entrepreneurial Behaviour, 112-139. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harms, R., & Groen, A. (2017). Loosen up? Cultural tightness and national entrepreneurial activity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 121, 196-204.

Harun, N.N. (2010). Entrepreneurial career aspirations among students of public higher education institutions. Malaysian Journal of Education, 35(1), 11-17.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. SAGE Publications.

Isenberg, D. (2010). How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution. Harvad Business Review, 88.

Isenberg, D.J. (2011). The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurships. The Babsos Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Project, 1(781), 1-13.

Jamil, F., Ismail, K., Siddique, M., Khan, M., Kazi, A. G., & Qureshi, M. I. (2016). Business Incubators in Asian Developing Countries. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6, 291-295.

Kamunge, M.S., Njeru, A., & Tirimba, O.I. (2014). Factors Affecting the Performance of Small and Micro Enterprises in Limuru Town Market of Kiambu County, Kenya. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655-674.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kee, D., mohd yusoff, Y., & Khin, S. (2019). The Role of Support on Start-Up Success: A PLS-SEM Approach. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 24, 43-59.

Khattab, I., & Al-Magli, O.O. (2017). Towards an Integrated Model of Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. Journal of Business & Economic Policy, 4(4), 80-92.

Liñán, F., & Alain, F. (2015). A systematic literature review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 907-933.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lockwood, P. (2006). Someone like me can be successful: Do college students need same-gender role models?. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 36-46.

Logaiswari, I., Zainab, K., & Kamariah, I. (2019). The Challenges Of Business Incubation: A Case Of Malaysian Incubators. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 44.

Marques, C.S.E., Santos, G., Galvão, A., Mascarenhas, C., & Justino, E. (2018). Entrepreneurship education, gender and family background as antecedents on the entrepreneurial orientation of university students. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(1), 58-70.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morgenroth, T., Ryan, M.K., & Peters, K. (2015). The Motivational Theory of Role Modeling: How Role Models Influence Role Aspirants’ Goals. Review of General Psychology, 19(4), 465-483.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moriano, J. A., Gorgievski, M., Laguna, M., Stephan, U., & Zarafshani, K. (2012). A Cross-Cultural Approach to Understanding Entrepreneurial Intention. Journal of Career Development, 39(2), 162-185.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mustapha, M., & Selvaraju, M. (2015). Personal attributes, family influences, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship inclination among university students. Kajian Malaysia, 33, 155-172.

Myers, D. (2014). The Theory of Planned Behaviour as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intention in the South African Jewish Community. November.

Noha, A.H. (2020). University business incubators as a tool for accelerating entrepreneurship: theoretical perspective. Review of Economics and Political Science, ahead-of-p(ahead-of-print).

Norita, D., Armanurah, M., Habshah, B., Norashidah, H., & Yeng Keat, O. (2010). Theoretical and practical entrepreneurship (2nd Edition). McGraw Hill Education.

Nurazwa, A., & Nor Kamariah, K. (2020). Motivating Factors for UTHM Students in Entrepreneurship. Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, 63-72.

Nurzulaikha, A., & Noor Aslinda, A. S. (2021). Relationship between Educational Support Factors and Student Interest in Entrepreneurship. 2(1), 1499-1508.

Sarasvathy, S.D. (2001). Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. The Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Seun, A.O., Abd Wahab, K., Bilkis, A., & Raheem, A.I. (2017). What motivates youth enterprenuership? Born or made. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 25, 1419-1448.

Sipola, S., Puhakka, V., & Mainela, T. (2016). A start-up ecosystem as a structure and context for high growth. In Global entrepreneurship: Past, present & future. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Spigel, B. (2017). The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

St-Jean, E., & Audet, J. (2012). The role of mentoring in the learning development of the novice entrepreneur. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(1), 119-140.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stam, E., & Van De Ven, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 809-832.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Suhaila, A., Suhaida, A.K., & Zaidatol Akmaliah, L.P. (2013). Entrepreneurial skills in technical and vocational education.

Syafiq, Z., Sheerad, S., & Norasmah, O. (2021). The Level of Entrepreneurial Culture and Entrepreneurial Leadership and Its Relationship with the Entrepreneurial Mind of Asnaf Children. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 6(3), 104-119.

Terjesen, S., & Wang, N. (2013). Coase on entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 173-184.

Tomy, S., & Pardede, E. (2020). An entrepreneurial intention model focussing on higher education. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(7), 1423-1447.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Turcan, R.V., & Fraser, N.M. (2018). The Palgrave handbook of multidisciplinary perspectives on entrepreneurship. The Palgrave Handbook of Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Entrepreneurship, 1-525.

Ullah, S. (2019). The effect of entrepreneurial ecosystems on performance of SMEs in low middle income countries with a particular focus on Pakistan.

Wan Mohd Zaifurin, W.N., Nor Hayati, S., Sabri, A., & Ibrahim, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial Tendency Among Secondary School Students in Terengganu State. 41(1), 87-98.

Wilson, C.A. (2013). Public Policy: Continuity and Change (2nd Editio). Waveland Press.

Xue, Y. (2018). The role of the entrepreneurial-oriented university in stimulating women entrepreneurship. University of Twente.

Zulelawati, B., & Yusni Zaini, Y. (2015). Trait Personaliti dan Hubungan Dengan Prestasi Akademik Bakal Guru di Sebuah Institusi Latihan Perguruan. Jurnal Bitara Edisi Khas (Psikologi Kaunseling), 8.

Received: 01-May-2023, Manuscript No. AJEE-23-13622; Editor assigned: 03-May -2023, Pre QC No. AJEE-23-13622(PQ); Reviewed: 17-May-2023, QC No. AJEE-23-13622; Published: 24-May-2023