Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 1

The Determinants of Consumer Trust during A Brand Name Substitution: The Moderating Role of the Country′s Image − The ′′Tunisiana−Ooredoo′′ Case

Kannou Ahmed, University of Tunis El Manar

Kaouther Saied Ben Rached, University of Tunis El Manar

Citation Information: Ahmed, K., & Ben Rached, K.S. (2024). The determinants of consumer trust during a brand name substitution: the moderating role of the country's image - the "tunisiana-ooredoo" case. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(1), 1-13.

Abstract

This article aims to understand the impact of retailer brand name substitution on consumer trust. Based on brand substitution research, this paper proposes variables that may explain consumer trust when a brand name is substituted. Thus, the emphasis is placed on the role of the country’s image in customer evaluations following the substitution. The results of this research highlight three variables that can contribute to building consumer trust during a retailer brand name substitution, namely (1) information about the change; (2) perceived quality of service place; (3) the similarity between the new and the initial brands. They also showed that the country’s image (Qatar) has a moderating effect on the relationship between trust and its determinants. This paper helps practitioners to identify the key success determinants that can easily transfer consumer trust from the old retailer brand to the new one. It reveals guidance for successful retailer brand name substitution.

Keywords

Brand name substitution; Communication about the substitution; Perceived quality of service place; Similarity; Country’s image.

Introduction

Brand name substitution has become a common management practice although it is a risky, expensive and time-consuming exercise (Miller et al., 2014; Collange, 2015; Bolhuis et al., 2018. Brand name substitution involves replacing a brand with less potential by a more strategic one in order to stimulate a substitution in consumers’ attitudes, perceptions and behaviours. Although mergers and acquisitions are among the most common reasons, other reasons such as the need to give the brand a new image (Muzellec and Lambkin, 2006; Merrilees and Miller, 2008), repositioning it on the market (Kaikati. 2003), or seeking hegemony (Collange, 2015) also play an important role. In Europe, for example, the historical operator France Telecom decided to abandon this name to become Orange in order to have a new social identity that aims at more coherence and simplicity. These changes did not spare the countries of North Africa, namely Tunisia, with the substitution Tunisiana-Ooredoo, as part of a globalization strategy implemented by the Qtel Company, Qatar Telecommunications.

Although this strategy is per se an opportunity for the brand in terms of competitive advantage and profitability, it nevertheless carries risks related, in particular, to the perception and reaction of the former brand’s regular customers (Descotes and Delassus, 2015; Collange and Bonache, 2015; Sridhar et al., 2016). In Tunisia, for example, a major boycott campaign on social networks was observed following the change of the telecommunications brand Tunisiana to Ooredoo (Zghidi et al., 2015; Smaoui and Smiri, 2016). This form of resistance is generally linked to animosity towards the Ooredoo brand’s native country (Qatar). It is rather a political, cultural and economic animosity born after the “Arab Revolutions” due to Qatar’s foreign policy that several parties regard as interventionist (Smaoui and Smiri, 2016). This situational animosity can destroy customers’ trust in the brand, resulting in a drastic loss of brand loyalty. Indeed, despite the central position of trust in the literature review (Ducroux 2009; Kaabachi, 2015; Lacoeuilhe et al., 2017), it is quite surprising to note that few studies have analysed the impact of brand trust in the case of brand name substitution. The new brand must be legitimate to consumers; otherwise it will not be credible and will fail in the market.

Our study, then, aims to fill this gap in the literature at least partially by proposing a research model to explain the determinants of consumer trust in brand name substitution and showing the influence of the country’s image on consumer behaviour. Therefore, the results of our research will provide managers with a list of determinants, allowing them to reduce negative consumer reactions to the brand substitution and to preserve the trust capital of the former brand in case of a brand substitution.

A quantitative study was conducted with 350 individuals and highlighted the determinants of consumer trust during a brand name substitution. The results obtained will reduce the negative reactions of consumers to the brand substitution and preserve the trust capital of the former brand in the event of a substitution.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The Principle of Reasoning by Analogy

Reasoning by analogy is a scientific research topic in which several researchers have taken an interest. It is considered an essential form of inductive reasoning (Cauzinille-Marmèche et al., 1985) and is omnipresent in our daily life, especially when we have to deal with new situations (Sternberg, 1977). Thus, reasoning by analogy makes it possible to facilitate the knowledge transfer from an already known situation to an unknown situation (Sander, 2000; Holyoak, 1984). An abstract knowledge structure describing the relationships between the two situations or domains would be created by this transfer, and this new structure would facilitate future knowledge transfers to other domains (Holyoak et al., 1984; Gentner and Holyoak, 1997). It is possible to transfer the knowledge already acquired to new areas that the individual organises by analogy. In the context of our research, to establish an analogy, it is necessary that the entities of the two fields studied be similar. The objects are then different but the roles that each plays in the structure are identical, it is a question of substantial analogy when the two entities “share a common property” (Nagel, 1961). This means that the analogy compares two domains but which share similarities in their structures or in their relationships.

In marketing, the concept of reasoning by analogy was the subject of a lot of research. For example, some research shows that the retailer brands accomplish many functions by analogy to the product brands (Kapferer, 2007; Ambroise et al., 2010; Fleck and Nabec, 2010). They show that the retailer brand, like the product brand, allows the consumer to identify the brand's offer, differentiate it from competitors’, offer a of a certain level of quality guarantee of the product-service offer, validate one's personality, and provide symbolic, hedonistic and experiential benefits (Kapferer, 2007; Fleck and Nabec, 2010). Other research uses the concept of retailer brand equity, also based on a theoretical analogy with brand equity (Arnett et al., 2003; Pappu and Quester, 2006; Jinfeng and Zhilong, 2009; Calvo-Porral et al., 2015; Gil-Saura et al., 2017).

Collange (2008) and Descotes and Delassus, 2015 relied on the work carried out on brand extensions which, according to them, presents similarities with the problem of brand substitution. The practice of brand extension is based on the principle that the consumer will transfer their attitude towards the renowned brand, supposedly positive and favourable, to the unknown extension, and that this will encourage them to buy it (Collange, 2008). Similarly, the practice of brand substitution is based on the principle that the consumer will transfer their attitude towards the brand (known), supposedly positive and favourable, to the new brand (known or unknown) and that this will encourage them to continue to buy it. From the above, it seems very legitimate to us to refer by analogy to prior research carried out on brand substitutions in order to identify the determining variables of brand trust in the case of retailer brand substitution. Therefore, we assume, by analogy to brand substitution, that retailer brand substitution is also based on the principle that the consumer can transfer their trust and attitude from the old (known) brand, supposedly positive and favorable, to the new one (known or unknown), and that this will encourage them to continue to frequent it.

Information about the Substitution

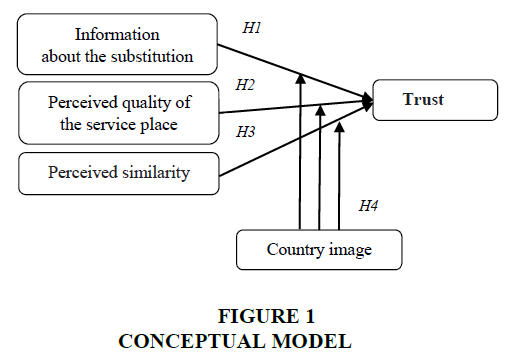

According to Callon (1998), “the only antidote to combat the poison of mistrust is to amplify information”. Delassus et al., (2014) stress that the absence of information on substitution and its benefits, the lack of comprehension of the decision’s rationale, or the perception of dissonant arguments can lead to resistance. Communication about the substitution then, presents one of the most important factors for the substitution to be successful (Giangreco and Peccei, 2005; Plewa and Veale, 2011; Collange, 2015; Delassus and Descotes, 2018). It allows to reduce the surprising impacts of the substitution, to improve trust in companies and to limit the effect of negative emotions on attitudes towards brand substitution (Lomax and Mador, 2006; Collange and Bonache, 2015). We then assume, just like brand substitution (Descotes and Delassus, 2015; Collange, 2015), that if the retailer informs consumers in a transparent and progressive way about the substitution, they will tend to accept the substitution easily. This improves trust in the new brand and thus limits the effect of negative reactions towards brand substitution. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis Figure 1:

H1: The more consumers are informed in advance of the brand substitution, the stronger the trust in the new brand.

Perceived Quality of the Service Place

If the brand name shares a number of similar points with the product brand, it also has specificities that should be taken into account. Large or specialized retail stores were perceived by consumers as service locations (Ailawadi and Keller, 2004; Bergadaà and Del Bucchia, 2009; Collange, 2015). A service place is above all a certain type and level of service provided in a service location, with a certain design, personnel, etc; it is an encounter (Collange, 2015). The work carried out on service locations identified two important aspects: an affective aspect of attachment to the place, but also a cognitive aspect of the perceived quality of the service location (Gross and Brown, 2006; Ramkissoon et al., 2013; Collange, 2015). The affective and symbolic aspect refers to the client’s preferences, as well as their feelings, emotions, and expectations towards the place (Proshansky, 1978; Brocato et al., 2015). The cognitive aspect is expressed in the judgment made by the customer on the overall excellence or superiority of the service place, resulting from the comparison between their expectations and the perceived performance of the latter (Parasuraman et al., 1988 ; Brocato et al,. 2015). In this regard, we chose to include the cognitive variable “perceived quality of the service place” in our model. This choice is motivated not only by the role that this variable can play in the acceptance of the brand name substitution, but also by its important role in building consumer trust during a brand name substitution. However, we expect that the perceived quality of the new brand’s place service will facilitate its acceptance by the customer, with a high perceived quality of the place service encouraging the customer to continue to trust the substitute brand. Hence, we make the following hypothesis:

H2: The higher the perceived quality of the service place, the stronger the trust in the new brand.

The Perceived Similarity between the Two Brands

Perceived similarity plays a crucial role in transferring knowledge and attitude from a known stimulus to another (Grigoryan, 2020). The greater the similarity between two objects, the more knowledge and attitude will be transferred from a very known object to a less known object (Martin and Stewart, 2001; Bhat and Reddy, 2002). In the context of a brand substitution, the reason why consumers can resist such a substitution can be explained by the theory of cognitive coherence, which was proposed by Festinger (1957). According to this theory, consumers always expect coherence even in the case of a brand name substitution. If inconsistencies or something unexpected occur, a state of dissonance can be created which can lead to negative feelings. However, consumers can try to cope with such dissonance by changing their attitudes, beliefs and behaviours according to various cues, for example by looking for similarity between the two brands (Martin and Stewart, 2001). In our case, the measure of similarity is based on the fact that both brands occupy an equivalent place in the market. If this condition is not fulfilled, this can lead to negative emotions felt by consumers and destroy their trust (Bhat and Reddy, 2002 ; Descotes and Delassus, 2015). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The perception of similarity between the substitute brand and the initial brand is likely to raise consumer’s trust in the new brand.

Country Image

In this study, the country’s image is identified as a moderating variable. It provides an indication of consumers’ perceptions, evaluations and beliefs regarding price, quality and risks associated with purchasing a brand in a given country (Kim, 2006; Koschate-Fischer et al., 2012; Dedeoğlu, 2019; Ramkumar and Jin 2019). Consumers can now choose between local and foreign brands (Fullerton and Kendrick, 2017). Some researchers specify that geographical origin can serve as a source of information, and can even be an important database in the decision-making process (Papadopoulos and Heslop, 2002), from which the consumer develops favourable attitudes towards the brand over time (Phau, 2000). Based on country-brand combinations, Diamantopoulos et al., (2011) showed the powerful influence of the native country on brand perception. Other researchers showed that consumers in developing countries have a more favourable attitude towards brands perceived as non-local beyond the evaluation of brand quality (Hui and Zhou, 2003). Therefore, in most developed countries, local brands are rated better than foreign brands (Dedeoğlu B, 2019). In Tunisia for example, the brand Tunisiana was a leader in the mobile telecommunications market. This brand was highly appreciated by consumers and had a great trust capital. Therefore, the substitution of the Tunisiana brand by Ooredoo was not appreciated by many consumers, and the disappearance of the local Tunisiana brand in favour of an international brand, that of Ooredoo, had caused some mistrust among Tunisians who launched boycott campaigns on social networks following this substitution (Mida et al., 2016; Gara Bach Ouerdian et al., 2018). This mistrust may be linked to a situational animosity, born after the “Arab Spring” following a foreign policy of Qatar (Ooredoo’s native country) that several parties consider as interventionist and partisan (Zghidi et al., 2015). We will then check the following hypothesis:

H4: The country’s image has a moderating effect on the relationship between information, perceived quality of the service place, perceived similarity between the two brands, and trust.

Methodology

Data Collection

This research is based on a survey conducted in Tunisia. It was carried out with a Tunisian private telecommunications operator “Tunisiana” which underwent an identity change under the name “Ooredoo”. Indeed, as part of a globalization strategy, Qtel (Qatar Telecommunications) decided to unify all its subsidiaries under a single brand name “Ooredoo” in order to bring together all its international activities under one single brand identity. Ooredoo, which already holds 75% of the shares in Tunisiana, increased its stake after signing, on December 31st, 2012, a preliminary agreement with the Tunisian government for the acquisition of an additional 15% of shares. The agreement thus increased the total Qatari holdings to 90% of the Tunisian operator’s capital. The remaining 10% are held by the Tunisian authorities (Bouali, 2017).

The data were collected from Tunisian consumers using a self-administered online questionnaire. Social networks such as “Facebook and WhatsApp” were also used to circulate the URL link of our questionnaire in order to use the so-called “Snowball” method (Marpsat and Razafindratsima, 2010). Finally, the administration of the questionnaire took place between March and July, 2016 and allowed us to collect 350 questionnaires. A large part of the sample was female (52.6%). 59% of consumers were between 25 and 60 years old. The buyers were divided according to their marital status (62% married and 38% single).

Measuring Scales

The operationalization of constructs was founded on the use of measurement scales tested in the marketing literature. The assessment of trust was carried out using 5 items from Kaabachi’s scale (2015). To measure the information about the change, 4 items adopted from Delassus and Descotes’ work (2018) were used. To measure the perceived quality of the service place, we used the 3-dimensional scale of Dabholkar et al., (1996) applied to the French context by Collange (2015). The perceived similarity between the two brands was measured by 3 items adapted from Collange (2008) and Bhat and Reddy (2002). To measure the overall image of the brand’s native country, we used the Laroche et al., (2005) scale applied to the Tunisian context by Zghidi et al., (2015). All items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 “Totally disagree” to 5 “Totally agree”.

Results of Measurement Scales

To confirm and validate our conceptual model, we resorted to confirmatory analysis (CFA) using the AMOS.21 software. We adopted the procedure of Fornell and Larcker (1981) in order to test unidimensionality, reliability, to calculate convergent validity and discriminant validity of each of the constructs. All scales were treated as first-order factors, except for perceived service quality, which was treated as a second-order factor (the values of each of the three factors of perceived service quality were calculated by taking the average of the factor items, and the factor values were used to assess unidimensionality). The results indicate an acceptable value for the different factors (Table 1).

| Table 1 Measurement Scale Of Unidimensionality Results |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unidimensionality Scale | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | TLI | CFI |

| Criteria | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Trust | 0.995 | 0.993 | 0.044 | 0.993 | 0.992 |

| Information about the substitution | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.045 | 0.996 | 0.998 |

| Perceived quality of the service place | 0.975 | 0.988 | 0.028 | 0.996 | 0.994 |

| Perceived similarity | 0.991 | 0.994 | 0.051 | 0.993 | 0.997 |

| Country’s image | 0.992 | 0.996 | 0.049 | 0.995 | 0.998 |

In order to check the reliability of our constructs, we used jointly the following two reliability indicators: Cronbach’s alpha (α ≥ 0.7) (Evrard et al., 2003) and Joreskög’s Rho (p ≥ 0.7) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The results presented in Table 2 confirm the reliability of the selected variables as they exceed the recommended minimum 0.7 threshold.

Furthermore, we observe that the conditions of convergent validity were met as the values of the average extracted variance (AVE) (rVC) are above 0.5 (Table 2). As for the discriminant validity, the acceptance conditions are met given that the average extracted variance is greater than the square of the correlation between the latent variables (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

| Table 2 Results Of Scales’ Reliability And Validity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cronbach alpha (α) | Jöreskog Rho (ρ) | AVE |

| Trust | 0,831 | 0,857 | 0,768 |

| Information about the substitution | 0,824 | 0,853 | 0,745 |

| Perceived quality of the service place (Relation) | 0,843 | 0,862 | 0,791 |

| Perceived quality of the service place (Access) | 0,798 | 0,819 | 0,722 |

| Perceived quality of the service place (Ambiance) | 0,801 | 0,833 | 0,741 |

| Perceived similarity | 0,807 | 0,829 | 0,742 |

| Country’s image | 0,844 | 0,863 | 0,688 |

Significance of Causal Links and Validation of Hypotheses

The global structural model test is performed by first assessing its fit to the data. Then, the direct structural links are analysed. The structural model fit is evaluated using the fit indices previously used in the context of the measurement model validation. We use the maximum likelihood estimation method on the covariance matrix (Kline, 2010). Table 3 shows that the model fits the data well for the overall sample; χ2/df 1.677; RMSEA 0.053; GFI 0.87; AGFI 0.89; TLI 0.95; NFI 0.91; and CFI 0.97. Only the GFI and AGFI values are below the 0.90 threshold, but it is known that these two indices are sensitive to sample size and model complexity and therefore do not call into question the overall fit of the model (Kline, 2010; Roussel et al. 2002).

| Table 3 Structural Equation Modelling Criteria And Results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Criteria | Authors | Values |

| χ2/df | <3 | Pedhazur and Pedhazur Schmelkin (1991) | 1,677 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | Roussel et al., (2003) | 0,053 |

| GFI AGFI |

>0.9 | Bentler and Bonett (1980) | 0,87 0,89 |

| NFI | Between >0.8 and 0.9>0.9 | Mulaik et al., (1989), Segars and Grover (1993), Hair et al., (1998), Bentler and Bonett (1980) | 0,91 |

| CFI | 0,97 | ||

| TLI | 0,95 | ||

Test of Direct Effects

The results of the theoretical framework reveal that three hypotheses are validated. Firstly, Table 4 shows that information about the substitution has a positive and significant impact on trust in the new brand (β = 0.421; p < 0.05). Secondly, the relationship between perceived quality of the service place and trust is highly appreciated (β = 0.293; p < 0.01). Finally, the results show a significant effect between perceived similarity and trust (β = 0.351; p < 0.01). It should be noted that these factors do not contribute in the same way to the explanation of trust in the “Ooredoo” brand. Indeed, our model reveals that the influence of information about the substitution and the perceived similarity on trust in “Ooredoo” is relatively more important. Finally, the measurement model of this research then allows us to confirm the hypotheses H1, H2, H3.

| Table 4 Relationship Between Trust And Its Determinants |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | Paths (VID → VD) | (Estimate/Standardized regression weight) β |

C.R. | ρ |

| H1 | INFO → TRUST | 0,421 | 0,595 | ** |

| H2 | QPLS → TRUST | 0,293 | 0,489 | *** |

| H3 | PSIM → TRUST | 0,351 | 0,545 | *** |

| Note(s): Significant at: **p, 0.05 and ***p, 0.001 levels ns: not significant) (INFO: Information about change; QPLS: Perceived quality of the service place; SIM: Perceived similarity) | ||||

The Moderating Role of the Country Image

In order to verify the moderating role of the country’s image (Qatar) at the information level, the perceived quality of the service location and the perceived similarity on trust, a full invariance multi-group analysis was conducted (Roussel et al. 2002). We identified 2 groups (positive country image versus negative country image) according to the classification of dynamic clouds (K-Means) (Vo and Jolibert 2005). We will then use the Chi-square difference test to verify the presence of the moderating effect of the country’s image at the level of each relationship.

The calculated difference of the chi-square is significant at a threshold of 5% (p = 0.000) and shows that the links between the independent variables (information, similarity and perceived quality of the place of service) and the dependent variable (trust in the new brand) depend on the country’s image. Therefore, we can accept hypothesis H4. In this regard, we can conclude that the country’s image (Qatar) has a moderating effect between trust and its determinants.

Table 5 shows that the impact of information, perceived quality of the service place and similarity on trust in the new brand is positive and significant for each of the two groups of respondents. Furthermore, the comparison between the two groups shows that this impact is even more important when the country’s image is perceived as positive by consumers, whereas this is not the case when the country image is perceived as negative by them.

| Table 5 Testing The Moderating Effect Of The Country Image |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Group 1: Negative country image | Group 2: Positive country image | ||||||

| H4 | Standardised coefficients | CR | P | Standardised coefficients |

CR | P | ||

| TRUST | <--- | INFO | 0,198 | 1,903 | ** | 0,426 | 3,839 | ** |

| TRUST | <--- | QPLS | 0,175 | 2,412 | 0,018 | 0,390 | 3,451 | ** |

| TRUST | <--- | SIM | 0,241 | 2,433 | ** | 0,391 | 5,018 | ** |

| Note(s): Significant at: **p, 0.05 and ***p, 0.001 | ||||||||

Conclusion, Implications, Limits and Extensions

The research attempts to present some key factors that managers should take into account in the case of a brand name substitution in order to foster consumer trust towards the new brand name. Therefore, this research has both theoretical and managerial implications. From a theoretical perspective, to extend previous research on brand substitution (Collange, 2008; Descotes and Delassus, 2015), we propose, by analogy, a first reflection on the impact of brand name substitution on consumer trust. Thus, the integration of the country’s image (Qatar) as a moderating variable remains almost absent especially at the level of studies on brand substitution. Therefore, highlighting this moderating variable constitutes an opportunity in favour of specifying the relationships between trust and its determinants.

From a managerial point of view, our research provides companies with a tool to guide them in the implementation of a brand substitution. Thanks to this tool, they could accurately estimate the extent to which consumer trust is transferable to the substitute brand. Indeed, our paper identifies the three conditions to be met for the brand substitution to be accepted by customers and remain loyal to the brand: (i) the brand substitution must be communicated before and after the change of brands, (ii) the perceived quality of the service location must be more attractive than that of the old brand and (iii) the new brand must also be as close as possible to the old brand.

Furthermore, the results of our study show that the positive or negative evaluation of the country’s image (Qatar) can affect the cognitive and affective evaluations of the brand as well as the behaviour related to it. More precisely, we found that the country’s image (Qatar) negatively moderates the relationship between trust and its determinants when the image is perceived as negative. This influence can be linked to a situational animosity, born after the “Arab Spring” due to Qatar’s foreign policy (country of origin of Ooredoo) that several parties consider as interventionist and partisan (Zghidi et al., 2015). However, managers must try to make the new brand legitimate to consumers in order to better elicit their trust. Managers are called in this case to play a driving role in the acceptance of the substitution. Indeed, when they organize a merger/acquisition operation, they must anticipate what could cause negative reactions and try to limit them as much as possible. Furthermore, in case of a popular and previously perceived local brand, it is important to avoid emphasizing the geographical origin of the new brand to avoid consumers’ negative reactions. As Kapferer (2002) points out, some local brands are leaders and often have significant value to customers. Managers who have such a strong local brand should capitalize on this advantage.

They can avoid clearly announcing the new brand’s geographical location, especially if some customers probably have a negative perception of the image of the native country. Finally, preparing the substitution program, providing information and listening to consumers, a gradual transition to the new brand, and establishing a prior climate of trust towards the new brand, appear as the actions the manager must undertake in order to lead the change to the new brand and, therefore, ensure the company’s lasting capital and intangible assets.

Like all research, our research also has a number of limitations. First, it only focused on two specialized service brands (two private telecommunications operators). This choice allows us to generalize our results to a large part of telecommunications brands, but not to other types of brands such as food or petroleum brands. Second, our respondents represented a convenience sample of consumers. Therefore, they are not representative of all Tunisian consumers. Finally, our research focused solely on the key determinants of success of a brand substitution from the consumer’s perspective, without incorporating the effect of the chosen substitution strategy, which can obviously influence the staff in contact with customers who work at the store, which is a more difficult factor to control.

Three research paths seem particularly interesting to us. Firstly, taking into account marketing action variables such as the effect of communication in building consumer trust towards a brand that has substituted its name. Secondly, it seems important for us to expand the scope of our research to other brands such as food retail brands (Carrefour, Monoprix, MG, etc.). For example, the Champion brand has become Carrefour-Market, the food retail brand Promogro has become MG (Magasin Général), and the petrol brand OiLibya has become OLA Energy. It would therefore be useful to expand the model we have developed to other cases of brand name substitution, taking into account their specificities. Finally, it seems interesting to choose a qualitative methodology that seems relevant to us in order to gain a better understanding of the different levers that can reduce consumer resistance to a brands substitution.