Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 1S

The Behavioural Intention among Young Adults in Thailand to Purchase Fashionable Clothing: Mediating the Role of Information Accessibility

Win Min Thein, Bangkok University

Zaryab Sheikh, Northumbria University

Samrat Ray, International Institute of Management Studies

Kumar D, SBIIMS

Citation Information: Thein, W.M., Sheikh, Z., Ray, S. & Kumar, D. (2024). The behavioural intention among young adults in Thailand to purchase fashionable clothing: Mediating the role of information accessibility. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S1), 1-15.

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of this study is to investigate the aspects that may influence individuals’ behavioural intentions to purchase fashionable clothing in Thailand. Design/methodology/approach: The behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing items among Thai young adults motivated the conduct of this study. We gathered data from 224 individuals, aged 18 to 45, and using structured questionnaires from a diverse population of university students, workers, and professionals across different industries in Thailand. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were employed to analyse the validity and reliability of indicators and corresponding constructs. Additionally, structural equation modelling (SEM) was applied to validate the hypothesised model and research hypotheses using SPSS and AMOS software. Findings - The data analysis revealed that the accessibility of information considerably mediates the association between fashion involvement and the behavioural intention to purchase fashion clothing. Contrary to the prediction, fashion involvement had no direct influence on young adults' behavioural intention to purchase fashion clothing items in Thailand. The article finishes with an overview of the significance of the findings and future research directions. Originality/value – This study provides empirical insights from the individual perspective of social media platforms into the drivers of fashion clothing purchasing behaviour among young adults in Thailand.

Keywords

Information Accessibility, Fashion Involvement, Purchase Intention, Fashion Clothing, Social Media.

Introduction

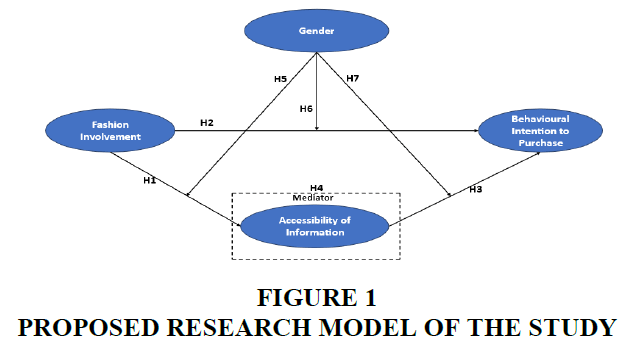

The purpose of this research is to investigate the influencing factors that affect behavioural intentions to make purchase decisions for fashionable clothing items. The behavioural intention to purchase is defined as the dependent variable. From the literature review below, the independent variable is fashion involvement, and accessibility of information plays a mediator role between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase. The demographic factor gender moderates the effects between the correlated variables. The research questions presented in this paper are: (i) What factors affect the behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing among young adults’ social media users in Thailand? (ii) How do these factors' correlation and interaction affect the behavioural intention to purchase fashion clothing items?

Consumer purchase intention has been a major focus for behavioural researchers because it is widely accepted as the immediate antecedent to purchase (Lim & An, 2021). Although research on factors influencing purchasing intention has been well established, the role of social media marketing in the post-pandemic as a new factor in behavioural intention to make purchase decisions requires a re-examination of its contemporary role in purchasing clothing items in the context of young adults in Thailand. Social media began as a way for individuals to stay in touch with friends and family, but it has grown into a place where people learn about goods and services (Wiese et al., 2020). Due to the rising role of online networking in the social environment, social media marketing is becoming an increasingly attractive method of advertising, as it allows brands to advertise in a more targeted and personalised manner (Worldnoor, 2021). Social media has played an influential role in the global business environment, allowing marketers to form close connections with customers, create brand engagement, build brand loyalty, influence trust, and influence behavioural intention to make purchase decisions (Kim, 2021).

With the establishment of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations economic community in 2015, ASEAN countries are considered a vibrant region, teaming with the infusion of technologies and social media usage in their consumer markets. Social media is a significant source of communication in Thailand's clothing and textile industry because it combines communication channels and e-commerce platforms, allowing consumers to share and search for information. Industry contributes significantly to the country's economy, accounting for around 17% of its GDP. The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 reduced textile industry growth by 1 billion USD; fortunately, it has recovered and is expected to reach 7.21 billion USD by 2026 (Statista, 2022; Fibre2Fashion, 2022). Since that time, marketers have been looking for a more cost-effective online communication medium to maintain sales figures. In January 2024, Thailand had a population of 71.85 million people, including 63.21 million internet users. This figure is equal to the internet penetration rate at 88.0 percent of the total population (Data Reportal, 2024). Traditional distribution methods have suffered as consumers increasingly rely on online information about goods and services. The role of social media marketing has evolved significantly because it not only influences customer purchasing intentions but also greatly enhances brand exposure and loyalty (Laksamana, 2018; Gupta et al., 2021).

The study of Thai consumers purchasing fashion clothing in department stores and small retail outlets by (Lerkpollakarn & Khemarangsan, 2012) mentioned that there have been a number of studies on consumer purchase decisions for clothing items in Thailand. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic may alter consumer behaviour, particularly among young adults in Thailand, when it comes to buying fashionable products. Thailand's economic situation influences how individuals make purchases for non-food or non-essential things such as clothing (Leong & Chaichi, 2021; Ong et al., 2021). The economic downturn had an impact on Thailand's consumption patterns. The pandemic also had an impact on the fashion industry. Hence, social media is an inexpensive and user-friendly tool that provides a direct connection between a brand and its consumers. Understanding the determinants that prompt consumers to interact with a brand on social media platforms is of great importance for marketers across the industry (McClure & Seock, 2020).

Thus, the purpose of this study is to examine the factors that influence young adults’ behavioural intentions to purchase stylish clothing in Thailand. The primary goal of this research is to investigate how characteristics such as fashion involvement, information accessibility, and gender affect intention and behaviour while purchasing attractive clothing products (Gautam & Sharma, 2018; Mardjo, 2019; Koca & Koc, 2016; Ho Nguyen et al., 2022). Firstly, consumers' level of fashion involvement greatly impacts the factors that determine their willingness to buy fashionable clothing (Gautam & Sharma, 2018). Consumers' fashion involvement is affected by their materialism, gender, age, mood, colour, taste, personal style, and attraction to certain clothes (Lerkpollakarn & Khemarangsan, 2012). Secondly, the accessibility of information is a significant factor in predicting online purchasing intentions due to the survey by (Khan et al., 2017) on Internet banking acceptability in Pakistan. Lastly, the study conducted by (Koca & Koc, 2016) reveals that male and female customers exhibit distinct approaches in their decision-making and purchasing behaviour while buying clothing products for various reasons. Young people represent a significant time of life in which a person transitions from dependence to adulthood. At each stage, young people have their own distinct perspective and selection of clothing. Young adults are the primary focus of many marketing campaigns for diverse products, as they are potential purchasers with strong preferences for clothing items (Sharma & Jain, 2017). Thus, it was considered appropriate to conduct research on the fashion clothing purchases of young adults in Thailand. The modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model is applied to test the hypotheses in addition to the fashion involvement theory. This is in response to (Venkatesh et al., 2003) to apply the UTAUT model in different contexts and with different variables.

Literature Review

UTAUT Model

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) by (Venkatesh et al., 2003) is one of the most widely accepted theories to explain the individual behaviour of using and applying Web 2.0 technologies such as blogs, wikis, and social media in a dynamic marketing environment. This theory not only encompasses numerous technologies and contexts but also successfully explains how to use certain technologies (Erjavec & Manfreda, 2022; Loureiro et al., 2018). Among the variables from UTAUT, “performance expectancy” could be defined as the degree to which the user believes in the performance of the technology and whether it could be useful and supportive of the business objectives. In the case of social media marketing in the clothing industry, how much technology can provide information in their purchase decision. So far, the UTAUT is a comprehensive IT adoption theory (Sheikh et al., 2017).

Fashion Involvement Theory

Based on the fashion involvement theory by (Tigert et al.,1976), the scholars (Engel et al., 2000) defined fashion involvement as the perceived personal relevance or interest of the consumer in fashion clothing. In the fashion involvement situation, O’Cass (2004, pp. 870) identified fashion involvement as "the extent to which consumers view fashion-related activities as central to their lives." It is important to understand the factors that influence consumers' engagement with a brand on social media platforms, as well as the consequences of such involvement. This paper uses UTAUT in cooperation with fashion involvement theory as a theoretical background for the role of social media in purchasing behaviour among young adults’ consumers in Thailand.

Social Media Marketing

The acceptance and use of technology, such as social media, has become part of the purchasing decision-making process. Like other purchasing decision-making contexts, the purchase of clothing items follows the fashion trend of the time. Social media enables the communication of trends and developments. For example, social media marketing has become an active part of the marketing process in many industries to promote a product or service (Felix et al., 2017).

The use of social media platforms and websites to promote a product or service. It is becoming useful with its added data analytics capabilities. Most social media platforms have built-in data analytics tools, enabling companies to track the progress, success, and engagement of ad campaigns (Shaltoni, 2016). For instance, algorithm-driven social media content has grown in popularity over recent years (DeVito et al., 2017). The application of social media for marketing purposes affected all industries. The fashion industry in Thailand is no exception.

Fashion Involvement

The first determining factor for behavioural intention to make purchase decisions is fashion involvement. Fashion makes a person feel good, especially those who are the first to purchase new products presented by external factors drive and inspire a consumer's cognitive and behavioral decision-making processes through a sense of involvement, a motivational state that manifests itself in the provision of encouragement (Peter & Olson, 2010). Fashion involvement refers to the consumer's perceived personal relevance or interest in fashion clothing (Engel et al., 2005). Fashion involvement is the degree to which an individual explores several fashion-related concepts, such as awareness, knowledge, interests, and reactions. Factors such as enduring, situational, cognitive, or affective involvement and indicate how the consumer interacts with the object. The concept of fashion involvement concerns the way buyers engage with fashion products (Colombage & Rathnayake, 2020).

Tigert et al. (1976) found that fashion involvement is composed of five dimensions of fashion adoption-related behaviour, such as “(1) fashion innovativeness and time of purchase; (2) fashion interpersonal connection; (3) fashion interest; (4) fashion knowledge ability; and (5) fashion awareness and reaction to changing fashion trends.” Fashion involvement can be characterised as the consumer's perceived emotional attachment and interest in fashion clothes (O’Cass, 2000). Fashion involvement is linked to product knowledge, which refers to the understanding of brands within a specific product category, the settings in which the product is used, its attributes, the frequency of its use, and personal experience with fashion clothes (Vieira, 2009).

According to the study of fashion clothing consumption by (O'Cass, 2004) and (Gautam & Sharma, 2018), involvement in a fashion product may take place in four different ways, such as "product involvement; purchase decision involvement; advertising involvement; and consumption involvement." Each of these levels of involvement covers everything from the pre-purchase stage to post-purchase decisions. Due to the increasing emphasis on consumer behaviour research, the importance of fashion consumers’ involvement in studies has grown (Silva et al., 2019). The significance of fashionable clothes in our lives has increased due to the widespread emphasis on material belongings, particularly those of young adults’ consumers (Klerk, 2020). This statement is supported by the findings of (Islam et al., 2018) comparative study of young adults and adolescents, which revealed that while both age groups are materialistic in a broad sense, young adults are exceedingly materialistic in particular due to their extensive socialisation and social media usage. This study investigates the relationship between fashion involvement and the behavioural intention to make purchase decisions for clothing items. The behavioural intention to purchase fashion clothing can be significantly affected by fashion involvement, and therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Fashion involvement has a significant impact on the accessibility of information.

H2: Fashion involvement has a significant impact on the behavioural intention to purchase.

Accessibility of Information

The second determining factor for behavioural intention to make purchase decisions is the accessibility of information. According to the study of the reputation of social media platforms among young adults by (Ho Nguyen et al., 2022), the significance of accurate, current, and comprehensive information on the online platforms supports having confidence in social media marketing. One possible explanation is that respondents' trust in social media increased because of the assistance they received in evaluating online products, e-vendors, and making more purchasing decisions using high-quality information available on social media (Mardjo, 2019). People receive online social support from various social media platforms which help them to take well informed purchase decision (Sheikh et al., 2019). The marketers of fashion clothing in Thailand made it available for online purchasing; therefore, accessibility to information is a relevant factor in determining the purchasing decision among young buyers who engage in online shopping.

With the use of online social media, consumers spend less time and effort gathering and examining information, thereby enhancing their experience, and increasing their level of accessibility to information about its accuracy and reliability. A study that looked at how electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) marketing systems were used in developing countries found a strong relationship between performance expectations in terms of accessibility of information, social media marketing content, sales promotion content, and behavioural intention to purchase when looking at it through the lens of social media marketing (Raji et al., 2019). Historically, consumer behaviour research in the fashion and clothing industry has mostly focused on time-based processes such as information processing and decision-making (O’Cass, 2000). We formulate the following hypotheses based on previous literature:

H3: Accessibility of information has a significant impact on behavioural intention to purchase.

H4: The accessibility of information plays a significant mediator role between fashion involvement and the behavioural intention to purchase.

The Role of Gender

The third determining factor for behavioural intention to make purchase decisions is gender. The previous study examined the factors that impact consumers' buying behaviour based on gender, with a specific focus on fashion trends, and revealed that most individuals buy clothing when they perceive a necessity to do so. Additionally, the study observed that women tend to purchase clothing more frequently than men to enhance their emotional well-being. On the other hand, the overall proportions reveal that men are more likely than women to purchase clothing to conform to fashion standards (Koca & Koc, 2016). The study of fashion involvement and meaning of brands by (Auty & Elliott, 1998) has shown that women are generally more attentive to the informative contents of advertisements compared to men. Additionally, there is a positive correlation between fashion consciousness and public self-consciousness, which suggests that women tend to place more emphasis on their own physical appearance (Auty & Elliott, 1998). Therefore, it is possible that women may have a greater emotional connection to fashion clothing compared to men, as women might place it with greater importance in their lives than men do (O’Cass, 2004). Additionally, understanding the moderating role of gender in the relationship between fashion involvement, accessibility of information, and behavioural intention to purchase clothing items in the context of young adults in Thailand becomes crucial for marketers in the industry. Consequently, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H5: Gender moderating impact on the relationship between fashion involvement and accessibility of information.

H6: Gender moderating impact on the relationship between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase.

H7: Gender moderating impact on the relationship between accessibility of information and behavioural intention to purchase.

Behavioural Intention to Purchase

A purchasing decision is the result of a behavioural intention to purchase. Behavioural intention is defined as the likelihood of a consumer purchasing a specific product or service in the near future. It refers to an individual's motivation and intention to consciously develop a strategy or consider making a purchase with informativeness, creditability, dependability, and enjoyment for social media marketing (Charoensereechai et al., 2022). The term "behavioural intention to make purchase decisions" refers to an individual's motivation and deliberate planning to make a purchase with anticipation, willingness, and likelihood. Purchase decisions comprise three stages: product or service selection, learning, and judgement. This includes checking for product information, analysing it before making a buy, completing the transaction, and then experiencing happiness or discontent with the purchase (Charoensereechai et al., 2022; Ho Nguyen et al., 2022). As a result, good behavioural intention leads to a purchase, whereas a negative behavioural intention leads to rejection.

In the study of the purchasing behaviour of young adults in Thailand by (Jinarat, 2022), it was explained that social media has significantly impacted the purchase choices of young adult customers, as it offers greater convenience compared to traditional media and advances the development of politics, business, and marketing. The financial aspect of a purchase holds significance, regardless of the brand's reputation and the comfort and style of the clothing. The literature has identified behavioural intention as a dependent variable that relates to how consumers perceive brands on social media platforms as well as the degree of determination of an individual's engagement in a particular action. Purchasing propensity increases when the benefits outweigh the expenses. It is essential to understand consumer behaviour to forecast their behavioural intentions. Self-determination, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and perceived value are a few factors that affect behavioural intention to make purchase decisions (Jaara et al., 2021; Haryanto et al., 2019; Ho Nguyen et al., 2022). Therefore, a good understanding of the factors that influence consumers’ behavioural intentions to make purchase decisions on social media becomes crucial for the marketers of the clothing industry in Thailand. Thus, this study established the hypotheses in the conceptual framework, as shown in Figure 1.

By understanding the preferences of their target consumers, fashion apparel manufacturers and retailers can improve their ability to attract and retain their intended customers by understanding their target consumer preferences (Rajagopal, 2011). Solomon (2019) states that understanding consumer behaviour has a direct impact on marketing strategy. Companies can meet such requirements only to the degree to which they truly understand the needs of their customers. Therefore, marketing plans necessitate the integration of consumer behaviour insights into all aspects of a strategic marketing plan. Thus, this examination of behavioural intention in clothing purchases holds significant relevance for the industry.

Research Methodology

Research Design

A quantitative cross-sectional research approach was implemented through the use of a survey questionnaire containing statements adapted from prior studies. This survey method proves effective in exploring user behaviour and examining the relationships between different factors. The structured questionnaire, self-administered in nature, was meticulously crafted to assess variables within the proposed research model and gather demographic data. Each factor in the questionnaire was gauged through two indicators, with each indicator evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale spanning from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Opting for an online survey facilitated broader outreach, and the purposive sampling technique was employed. Within this study, both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were employed to examine the validity and reliability of indicators and corresponding constructs. Additionally, structural equation modelling (SEM) was applied to validate the hypothesised model and research hypotheses using SPSS and AMOS software.

Results and Discussion

Demographic Information Analysis

We employed a purposive sampling technique to gather a total of 245 participants from a diverse population of university students, workers, and professionals across different industries in Thailand. We refined the dataset after identifying and excluding 21 outliers, producing 224 valid questionnaires for subsequent data analysis. According to (Westland, 2010), this number exceeds the typical sample size of 200, which is considered sufficient for conducting a structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis. Table 1 provides detailed respondent profiles, revealing a sample composition of 49.6% males and 50.4% females. Most respondents (77.2%) are below 25 years of age, with the predominant occupation being students (78.1%). The remaining participants include professional and entry-level workers. A notable 89.3% of respondents express a daily preference for using social media.

| Table 1 Demographic Information Analysis Results | |||

| Demographic (n = 224) | Frequency | Percent | |

| Male | Male | 111 | 49.6 |

| Female | 113 | 50.4 | |

| Age | 18 - 24 Years | 173 | 77.2 |

| 25 - 30 Years | 13 | 5.8 | |

| 31 - 35 Years | 14 | 6.3 | |

| 36 - 40 Years | 14 | 6.3 | |

| 41 - 45 Years | 10 | 4.5 | |

| Work Experience | Professional worker | 28 | 12.5 |

| Entry level working adult | 21 | 9.4 | |

| Student | 175 | 78.1 | |

| Voluntariness | You like to use social media every day | 200 | 89.3 |

| You are willing to share information related to clothing on social media | 18 | 8.0 | |

| You do not hesitate to write negative feedback on social media | 6 | 2.7 | |

Preliminary Descriptive Analysis

According to the descriptive statistical analysis conducted in SPSS software, all standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values fall within the range of plus or minus 2. This implies that, based on the analysis results, participants in this study responded to questionnaire items in a manner consistent with a normal distribution. As a result, the dataset can be considered to exhibit normality, which is particularly relevant for T-test analysis. This analysis aims to explore significant differences between the means of indicators and the neutral value of 3 on their measurement scales (Table 2). Notably, the respondent expresses strong agreement that social media marketing effectively captures attention and interest in fashion clothing (BIP1, BIP2). Furthermore, social media users believe they can easily find product information and conduct price comparisons on these platforms (AOI 1, AOI 2). Specifically, participants demonstrate a robust positive attitude towards the idea of purchasing new clothing every month and wearing a new dress for every event (FI1, FI2).

| Table 2 Preliminary Descriptive Analysis Results | ||||||

| Indicators | Mean | Std. Deviation |

Skewness | Kurtosis | t | Sig.(2-tailed) |

| BIP1 | 4.38 | .570 | -.229 | -.754 | 36.092 | .000 |

| BIP2 | 4.21 | .578 | -.044 | -.309 | 31.200 | .000 |

| AOI1 | 4.35 | .573 | -.198 | -.705 | 35.351 | .000 |

| AOI2 | 4.33 | .668 | -.497 | -.743 | 29.800 | .000 |

| FI1 | 3.45 | .866 | .000 | -.660 | 7.713 | .000 |

| FI2 | 3.64 | .912 | -.019 | -.856 | 10.551 | .000 |

Exploratory Factor Analysis

To validate the observed variables corresponding to factors in the proposed research model, we employed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in SPSS software. The Principal Components Analysis (PCA) method was utilised with Varimax rotation. The Eigenvalues for each construct exceeded 1.0, indicating their significance. According to the criteria established by (Hair et al., 2010), indicators with loading coefficients of 0.5 or higher were deemed to accurately represent their respective constructs. The factor loading values for all questionnaire items ranged from 0.805 to 0.915. Consequently, the cross-factor loading analysis confirmed the existence of five constructs associated with six variables (refer to Table 3).

| Table 3 Exploratory Factor Analysis Results | ||||

| Constructs | Fashion Involvement |

Accessibility of Information | Behavioural Intention to Purchase |

Eigenvalues |

| FI2 | .915 | .082 | .055 | 2.341 |

| FI1 | .905 | .096 | .076 | |

| AOI1 | .019 | .877 | .146 | 1.425 |

| AOI2 | .170 | .856 | .135 | |

| BIP1 | .104 | .026 | .891 | 1.026 |

| BIP2 | .023 | .295 | .805 | |

Factor Correlation Analysis

Based on the Pearson correlation analysis results presented in Table 4, there is a notable and statistically significant correlation between age and the fashion involvement construct, as well as working experience, at the 0.01 significance level. Behavioural intention to purchase exhibits a significant correlation with voluntariness at the 0.05 significance level. Furthermore, Behavioural intention to purchase demonstrates significant correlations with the constructs of information accessibility at the 0.01 significance levels and fashion involvement at the 0.05 significance level.

| Table 4 Factor Correlations Analysis Results | |||||||

| Gender | Age | Work Experience | Voluntariness | BIP | AOI | FI | |

| Gender | 1 | ||||||

| Age | .063 | 1 | |||||

| Work Experience | .050 | -.798** | 1 | ||||

| Voluntariness | -.133* | -.072 | .036 | 1 | |||

| BIP | .103 | .137* | -.074 | -.168* | 1 | ||

| AOI | -.042 | -.075 | -.073 | -.015 | .341** | 1 | |

| FI | .054 | -.186** | .103 | -.018 | .161* | .213** | 1 |

Convergent Validity Analysis

Following the advice of (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), we used AMOS software to create the measurement model for the proposed research model (Table 5). This was the first step in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) process to make sure the model was valid. The standardised regression weights for all indicators surpass 0.5, ranging from 0.557 to 0.897. As a result, the findings indicate the successful establishment of convergent validity.

| Table 5 Convergent Validity Analysis Results | ||

| Construct | Indicators | Std. Regression Weight |

| Fashion Involvement | FI1 | 0.819 |

| FI2 | 0.837 | |

| Accessibility of Information | AOI1 | 0.698 |

| AOI2 | 0.821 | |

| Behavioural Intention to Purchase |

BIP1 | 0.557 |

| BIP2 | 0.897 | |

Discriminant Validity Analysis

When both the average variance extracted (AVE) and the composite reliability (CR) values are above 0.50 and 0.70, respectively, it means that the convergent validity and construct reliability are satisfactory. The AVE analysis yields results ranging from 0.557 to 0.686, surpassing the 0.5 threshold, while the CR ranges from 0.705 to 0.814, exceeding the recommended cut-off point of 0.70. Additionally, the square root of the AVE for each factor in this study is greater than the correlation coefficients between the factors. Table 6 demonstrates that the research model exhibits good AVE, CR, and discriminant validity, in accordance with the guidelines by (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

| Table 6 Discriminant Validity Analysis Results | |||||

| CR | AVE | FI | AOI | BIP | |

| Fashion Involvement | 0.814 | 0.686 | 0.828 | ||

| Accessibility of Information | 0.733 | 0.581 | 0.287 | 0.762 | |

| Behavioural Intention to Purchase | 0.705 | 0.557 | 0.168 | 0.470 | 0.746 |

Goodness of Fit Analysis

Goodness-of-fit indices exceeding 0.9 for the goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI), along with values less than 3.0 for CMIN/df and less than 0.08 for RMSEA, signify a well-fitted model. The goodness-of-fit statistics for the structural model in this study have surpassed the acceptable thresholds, as outlined in Table 7. As a result, the analytical results indicate that the research model provides a highly satisfactory fit for the data collected, as recommended by (Hooper et al., 2008).

| Table 7 Goodness of Fit Analysis Results | |||

| Recommended | Structural Model | Result | |

| CMIN/df | < 3.0 | 2.130 | Good Fit |

| GFI | > 0.9 | 0.982 | Good Fit |

| AGFI | > 0.9 | 0.935 | Good Fit |

| NFI | > 0.9 | 0.964 | Good Fit |

| CFI | > 0.9 | 0.980 | Good Fit |

| RMSEA | < 0.08 | 0.071 | Good Fit |

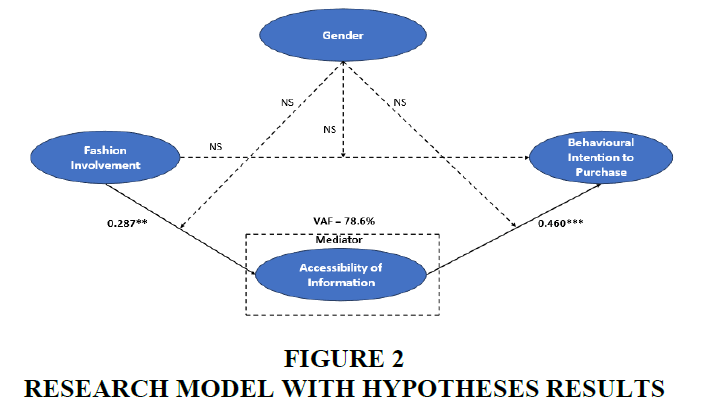

Direct Effects Analysis

Table 8 presents the outcomes of hypothesis testing (H1, H2, H3). In the context of social media, fashion involvement (β=0.287, t= 2.962, p = 0.003) demonstrated a statistically significant positive impact on the accessibility of information, thus supporting H1. The accessibility of information, in turn, exhibited a positive influence on behavioural intention (β=0.460, t=3.258, p = 0.001), confirming H3. However, the analysis results indicated non-acceptance of H2, signifying that fashion involvement did not have a statistically significant effect on behavioural intention to purchase.

| Table 8 Direct Effects Analysis Results | |||||

| Hypotheses | Std. Effect | t-Value | p-Value | Result | |

| H1 | FI → AOI | 0.287 | 2.962 | 0.003 | Support |

| H2 | FI → BIP | 0.036 | 0.430 | NS | Not support |

| H3 | AOI → BIP | 0.460 | 3.258 | 0.001 | Support |

Mediator Analysis

To identify mediation variables and ascertain their role (H4) between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase, the degree of Variance Accounted For (VAF) was calculated. VAF is determined by dividing the indirect effect (I → m → D) by the total effect

(I → D) Interpretation of the result is as follows: if it exceeds 20%, it signifies mediation, while less than 20% implies no mediation (Hair et al., 2010). The accessibility of information exhibited a substantial mediation effect of 78.6% between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase, as confirmed by the analysis results presented in Table 9. Consequently, H4 was validated, affirming the role of accessibility of information as a mediator variable.

| Table 9 Mediator Analysis Results | |||||

| Hypotheses | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAF | Result | |

| H4 | FI → AOI →BIP | 0.132 | 0.168 | 78.6% | Fully Mediating |

Moderator Analysis

The demographic factor of gender was examined as a potential moderator for the direct effects (FI → AOI, FI → BIP, AOI → BIP). The analysis of moderating effects was conducted in AMOS, utilising the proposed theoretical research model. AMOS calculates a critical ratio for differences, and a value exceeding 1.96 is indicative of a significant moderator effect (Hair et al., 2010). Table 10 displays the critical ratios for differences of direct effects, revealing that gender does not exert a significant moderating influence on these direct effects. Consequently, H5, H6, and H7 were not supported and are rejected.

| Table 10 Moderator Analysis Results | |||

| Hypotheses | Critical Ratio for Difference | Moderator | |

| H5 | FI → AOI | 1.444 | Reject |

| H6 | FI → BI | 1.518 | Reject |

| H7 | AOI → BI | 1.080 | Reject |

| Gender: (Male = 111, Female =113) | |||

Discussion

The result of this study confirmed the existence of five constructs associated with six variables in behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing items in Thailand, such as fashion involvement, accessibility of information, and behavioural intention to purchase online. Social media marketing effectively captures the attention and interest of young adults in the Thai fashion clothing industry, and users are willing to share information related to clothing items on social media platforms.

The Pearson correlation analysis results showed a significant correlation between age and the fashion involvement construct, indicating that age between 18 and 24, representing 77.2% of social media users, has the strongest behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing. This finding is in alignment with the previous studies by O'Cass (2004) and (Gautam & Sharma, 2018), which found that social media influences young consumers' involvement in fashion items through advertising and purchase decision involvement, leading to a stronger desire for material belongings (Klerk, 2020). This further adds to the findings that Thai young adults are more likely to buy fashionable clothing through social media websites. It may vary depending on age, as people have different preferences and decisions. There are age-related differences and impacts on attachment and utilisation. Sharma and Jian's (2017) study of young adults buying fashion apparel in India supports this result, revealing that they spend most of their money on clothes, cosmetics, and personal expenses. This study recognised age as a significant factor in the fashion clothing industry, and young adults in Thailand are voluntarily using social media to search for fashion-related information online. Younger individuals tend to prioritise their physical appearance more than older individuals in general. Previous studies agreed that clothing may play a more prominent role in the lives of young individuals, resulting in more involvement with fashion items among younger people compared to older individuals. (Auty & Elliott, 1998; O'Cass, 2000).

Young adults in Thailand demonstrated a strong positive attitude towards the idea of purchasing new clothing online every month and the desire to wear a new dress for every event. These findings are in alignment with previous research that examined the influence of social media marketing on behavioural intentions to purchase online through the accessibility of information (Ho Nguyen et al., 2022; Mardjo, 2019; Raji et al., 2019). The direct effects analysis revealed that fashion involvement had a statistically significant positive impact on the accessibility of information, which in turn had a positive influence on behavioural intention to purchase. However, the analysis results indicated non-acceptance of H2, signifying that fashion involvement did not have a statistically significant direct effect on behavioural intention to purchase. Given the increasing amount of social media usage and online shopping among young people in Thailand, the interest in fashion design is insufficient to arouse a desire to purchase clothing without accessing information to receive product information and conduct online pricing comparisons. The accessibility of information exhibited a substantial mediation effect of 78.6% in the relationship between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase, affirming the role of the accessibility of information as a mediating factor. Therefore, the accessibility of information is an essential component in influencing the relationship between fashion involvement and the behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing items on social media platforms in Thailand.

Theorical Contribution

The study’s findings provide a valuable theoretical contribution to extend the literature that contributes to the behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing items. This study used fashion involvement theory (Tigert et al., 1976) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and thus proposed that accessibility of information is a significant mediator in the relationship between fashion involvement and behavioural intention to purchase. Accessibility of information is part of performance expectancy in the UTAUT model, which is a strong predictor of behavioural intention. This study confirms the mediating role of accessibility of information in the contemporary perspective of young adults’ social media users in Thailand, particularly in the context of purchasing fashionable clothing items, as aligned with many scholars (Venkatesh et al., 2012; Ho Nguyen et al., 2022; Raji et al., 2019). The research model with the hypothesis outlined in Figure 2.

The study discovered that fashion involvement does not have a direct effect on the behavioural intention to purchase fashionable clothing in the context of young adults’ consumption in Thailand. Without the accessibility of information such as product-related information, price-related information, and retailer information, only fashion involvement cannot create the intention to purchase fashionable clothing among young adults in Thailand. Surprisingly, gender does not have a moderating effect on the relationship between fashion involvement, accessibility of information, and behavioural intention to purchase fashion clothing among young adults in Thailand. On the contrary, previous literature (O'Cass, 2004; Koca & Koc, 2016) mentioned that women may have a greater emotional connection to fashion clothing compared to men, as women might place it more important in their lives than men do.

Managerial Contribution

The study's findings have significant managerial implications for fashion marketers. The study demonstrates that information accessibility plays a crucial role in influencing young adults' propensity to buy fashion clothing items. While young people possess curiosity and creativity, the content and quality of information on a brand's social media page significantly influence their intention to make a purchase. For fashion marketers, ensuring the credibility and reliability of information and visually appealing design on social media pages, incorporating emotional and aesthetic elements, is essential. For example, using contrast colours, typography, a brand logo, etc. According to research findings, 89.3% of young adults’ social media users in Thailand are willing to engage with social media daily. The more informative the social media platform is, the more people engage in the purchasing process. The study by McClure and Seock (2020) on "examining the impact of brands' social media pages" supports this idea. The study revealed that within the context of social media, the informational aspects of these pages play an essential part in influencing people's engagement with the pages and their decision-making process regarding whether to make purchases from the brand.

Limitations and Future Scope of Research

This study's limitations could be due to the demographic characteristics of the participants. The study revealed that the respondents' age was significantly skewed towards a younger population. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, there was a failure to gather a diverse range of respondents in terms of demographics. Furthermore, most of the participants, who are young individuals, do not own a regular source of income, which makes it impossible to determine their income level for the purpose of the analysis. Fashion involvement can influence this demographic variable.

Conclusion

This study encountered limitations that can offer great opportunities for future research. Firstly, the research focuses solely on individuals who purchase fashionable clothing. This region implies that future studies could broaden their scope by exploring more industries, such as restaurants, medicines, and electronics. Furthermore, the study failed to incorporate the participants' income level into its analysis, which could potentially influence their behavioural intention to make purchase decisions. We can consider this a topic worthy of further investigation. Finally, this study was conducted exclusively in Thailand; therefore, the results may differ when analysed in other countries. Future studies should investigate the buying preferences for fashionable clothing in additional Asian countries.

References

Auty, S., & Elliott, R. (1998). Fashion involvement, self‐monitoring and the meaning of brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 7(2), 109-123.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Charoensereechai, C., Nurittamont, W., Phayaphrom, B., & Siripipatthanakul, S. (2022). Understanding the Effect of Social Media Advertising Values on Online Purchase Intention: A Case of Bangkok, Thailand. Asian Administration & Management Review, 5(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Colombage, V. K., & Rathnayake, D. T. (2020). Impact of fashion involvement and hedonic consumption on impulse buying tendency of Sri Lankan apparel consumers: the moderating effect of age and gender. NSBM Journal of Management, 6(2), 23-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

DeVito, M.A., Gergle, D., & Birnholtz, J. (2017). Algorithms ruin everything: RIPTwitter, Folk Theories, and Resistance to Algorithmic Change in Social Media. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 3163-3174).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Erjavec, J., & Manfreda, A. (2022). Online shopping adoption during COVID-19 and social isolation: Extending the UTAUT model with herd behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65, 102867.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Felix, R., Rauschnabel, P.A., & Hinsch, C. (2017). Elements of strategic social media marketing: A holistic framework. Journal of business research, 70, 118-126.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fibre2fashion.com. (2022). Sector overview: The fashion industry in Thailand.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gautam, V., & Sharma, V. (2018). Materialism, Fashion Involvement, Fashion Innovativeness and Use Innovativeness: Exploring Direct and Indirect Relationships. Theoretical Economics Letters, 8(11), 2444-2459.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gupta, S., Gupta, P., & Yadav, R. (2021). Understanding the Impact of Social Media on Consumers Attitude and Decision-Making Process. International Journal of Marketing & Business Communication, 10(1), 48-59.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Haryanto, B., Purwanto, D., Dewi, A.S., & Cahyono, E. (2019). How does the type of product moderate consumers’ buying intentions towards traditional foods? Journal of Asia Business Studies, 13(4), 525-542.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ho Nguyen, H., Nguyen-Viet, B., Hoang Nguyen, Y.T., & Hoang Le, T. (2022). Understanding online purchase intention: the mediating role of attitude towards advertising. Cogent Business & Management, 9, p.2095950.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M.R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit Dublin Institute of Technology. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., Hammed Z., Khan, I. U., & Azam, R. I. (2018). Social comparison, materialism, and compulsive buying based on stimulus-response-model: a comparative study among adolescents and young adults. Young Consumers, 19(1), 19-37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jaara, O., Kadomi, A., Ayoub, M., Senan, N., & Jaara, B. (2021). Attitude formation towards Islamic banks. Accounting, 7(2), 479-486.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jinarat, V. (2022). Online Purchasing Behavior of Generation Y Consumer in Northeast Thailand. Journal of Business, Innovation and Sustainability, 17(2), 150-162.

Khan, I.U., Hameed, Z., & Khan, S.U. (2017). Understanding online banking adoption in a developing country: UTAUT2 with cultural moderators. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), 25(1), 43-65.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kim, K.H. (2021). Digital and social media marketing in global business environment. Journal of Business Research, 131, 627-629.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Klerk, N. D. (2020). Influence of Status Consumption, Materialism and Subjective Norms on Generation Y Students’ Price-Quality Fashion Attitude. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 12(1), 163-176.

Koca, E., & Koc, F. (2016). A study of clothing purchasing behavior by gender with respect to fashion and brand awareness. European Scientific Journal, 12(7), 234- 248.

Laksamana, P. (2018). Impact of social media marketing on purchase intention and brand loyalty: Evidence from Indonesia’s banking industry. International Review of Management and Marketing, 8(1), 13-18.

Leong, M.K., & Chaichi, K. (2021). The Adoption of Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and trust in influencing online purchase intention during the Covid-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Science, 11(8), 468-478.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lerkpollakarn, A., & Khemarangsan, A. (2012). A Study of Thai Consumers behaviour towards fashion Clothing. The 2nd national and International Graduate Study Conference 2012, Bangkok, Thailand, Silpakorn University International College.

Lim, H.R., & An, S. (2021). Intention to purchase wellbeing food among Korean consumers: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Quality and Preference, 88, 104101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of interactive advertising, 19(1), 58-73.

Loureiro, S.M., Cavallero, L., & Miranda, F.J. (2018). Fashion brands on retail websites: Customer performance expectancy and e-word-of-mouth. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41, 131-141.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mardjo, A. (2019). Impacts of social media’s reputation, security, privacy and information quality on Thai young adults’ purchase intention towards Facebook commerce. UTCC International Journal of Business and Economics, 11(2), 167-188.

McClure, C., & Seock, Y.K. (2020). The role of involvement: Investigating the effect of brand's social media pages on consumer purchase intention. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 53, 101975.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

O’Cass, A. (2000). An assessment of consumers product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. Journal of economic psychology, 21(5), 545-576.

O'cass, A. (2004). Fashion clothing consumption: antecedents and consequences of fashion clothing involvement. European journal of Marketing, 38(7), 869-882.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Peter, J. P., & Olson, J. C. (2010). Consumer Behaviour and Marketing Strategy. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Rajagopal. (2011). Determinants of shopping behavior of urban consumers. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(2), 83-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Raji, R.A., Rashid, S., & Ishak, S. (2019). The mediating effect of brand image on the relationships between social media advertising content, sales promotion content and behaviuoral intention. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(3), 302-330.

Shaltoni, A.M. (2016). E-marketing education in transition: An analysis of international courses and programs. The International Journal of Management Education, 14(2), 212-218.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sharma, A., & Jain, R. (2017). Young Adults’ Preferences for Purchasing Apparel. Indian Journal of Family and Community Studies, 1(1), 1- 15.

Sheikh, Z., Islam, T., Rana, S., Hameed, Z., & Saeed, U. (2017). Acceptance of social commerce framework in Saudi Arabia. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1693-1708.

Sheikh, Z., Yezheng, L., Islam, T., Hameed, Z., & Khan, I.U. (2019). Impact of social commerce constructs and social support on social commerce intentions. Information Technology & People, 32(1), 68-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Silva, E.S., Hassani, H., Madsen, D.O., & Gee, L. (2019). Googling fashion: forecasting fashion consumer behaviour using google trends. Social Sciences, 8(4), 111.

Solomon, M. R. (2019). Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, Being. Pearson: New York.

Statista. (2022). Fashion – Thailand.

Tigert, D.J., Ring, L.J., & King, C.W. (1976). Fashion Involvement and Buying Behavior: A Methodological Study. Advances in consumer research, 3(1), 46-52.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B., & Davis, F.D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vieira, V. A. (2009). An extended theoretical model of fashion clothing involvement. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 13(2), 179-200.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, H., & Wang, Y. (2020). A review of online product reviews. Journal of Service Science and Management, 13(1), 88-96.

Wang, T., Yeh, R.K.J., Chen, C., & Tsydypov, Z. (2016). What drives electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites? Perspectives of social capital and self-determination. Telematics and Informatics, 33(4), 1034-1047.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Westland, J.C. (2010). Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modelling. Electronic commerce research and applications, 9(6), 476-487.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wiese, M., Martínez-Climent, C., & Botella-Carrubi, D. (2020). A framework for Facebook advertising effectiveness: A behavioral perspective. Journal of Business Research, 109(1), 76-87.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Worldnoor. (2021). The Role of Social Media and Its Importance in Modern Society.

Yu, S., & Hu, Y. (2020). When luxury brands meet China: The effect of localized celebrity endorsements in social media marketing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102010.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yuan, C.L., Kim, J., & Kim, S.J. (2016). Parasocial relationship effects on customer equity in the social media context. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3795-3803.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhang, X., Ma, L., & Wang, G.S. (2019). Investigating consumer word-of-mouth behaviour in a Chinese context. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(5), 579-593.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 06-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15009; Editor assigned: 08-Jul-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15009(PQ); Reviewed: 26- Aug-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15009; Revised: 26-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15009(R); Published: 21-Oct-2024