Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 1

Tax Avoidance Schemes in Cross-Border Digital Transactions in Indonesia

Hendri, Universitas Indonesia

Ning Rahayu, Universitas Indonesia

Milla S. Setyowati, Universitas Indonesia

Citation Information: Hendri, Rahayu, N., & Setyowati, M.S. (2022). Tax avoidance schemes in cross-border digital transactions in indonesia. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 26(1), 1-20.

Abstract

Research Aims: This Study aims examine and highlights issues related to tax avoidance schemes arising from cross-border digital transactions. Design/methodology/approach: This study employs qualitative research methods, qualitative research refers to research that aims to understand human or social problems based on a holistic picture, a series of words and sentences and informants’ reports carried out in natural settings or conditions. Data analysis is performed using the Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS), i.e. NVivo 12. Research findings: Digital transactions have also rendered more new business opportunities and led to trickle-effects for other supporting industries, among others, logistics, IT infrastructure, and e-commerce operators. The expeditious development of digital transactions has transcended jurisdictional boundaries and resulted in substantial problems in cross-border taxation. Theoritical contributions/Originality :The major issues faced by tax authorities pertain to tax avoidance practices carried out by several business actors in digital transactions through tax avoidance schemes that exploit existing regulatory loopholes. Practicioner/Policy implications :The action plans serve as an international consensus where G-20 member countries have mandated the OECD to formulate the necessary recommendations. Research limitation.Implications : The main focus of this research is the strategies undertaken by business actors in designing tax avoidance schemes in cross-border digital transactions. To date, however, the long-awaited international consensus has not been resolved.

Keywords

Electronic Commerce, Digital Transactions, Cross-Border Digital Transactions, Taxes, Tax Avoidance, Tax Avoidance Schemes in Cross-Border Digital Transactions.

JEL

F38, H2, K3.

Introduction

Electronic commerce refers to all forms of trade transactions of goods or services that rely on electronic media technology. These trading systems are also commonly known as digital transactions. Electronic commerce relies heavily on digital transmission as a medium of communication via software. As such, business transactions are more efficient for businesses and consumers. Initially, transactions through the digital system were only carried out among large companies, banks, and other financial institutions. Along with the development, the focus of digital transactions is inclining towards individual consumers’ demands. Eventually, electronic commerce is not only employed by large companies, as companies of all sizes may also take advantage of this system (Nugroho, 2006, p. 6).

Digital transactions are developing so rapidly that not only do they change people’s lifestyles but also alter transaction patterns that require innovative strategies from business entities. Digital transactions have also rendered more new business opportunities and led to trickle-effects for other supporting industries, among others, logistics, IT infrastructure, and e-commerce operators.

The development of digital transactions provides convenience for consumers. This has changed consumers’ shopping style from conventional shopping to online shopping through surfing the virtual world. Consumers are spoiled with convenience in terms of product information, payment methods, and delivery of goods ordered or purchased. This gives rise to a new trend in trade transactions that transcend jurisdictional and territorial boundaries. This new trend, however, poses issues in international taxation.

Current regulations in international taxation are not yet able to anticipate the development of these digital transactions. The problem with Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon taxes, or commonly known as GAFA Tax, is a challenging tax issue for tax authorities in various countries. Problems emerging from these cross-border digital transactions contribute to loopholes being taken advantage of by some foreign business actors to reap more profits, specifically, in terms of taxes. Transactions dependent on technology transmission are not paralleled by a comprehensive tax system, thus resulting in opportunities for tax avoidance schemes.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, commonly known as the OECD, has declared these issues an international consensus to be resolved collectively. The OECD, with its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Action Plan, or frequently referred to as BEPS Action Plans, has formulated several digital-transaction-related recommendations. To date, however, the international consensus to address these issues has not been resolved.

Literature Review

Tax Policies

Effective implementation of tax policy plans are only possible if the limits and administration of taxes are taken into account. According to Soemitro (1973), at present, fiscal policy has a broader meaning, i.e. everything related to government efforts to stabilize or promote the level of economic activities. This is in accordance with John F. Due’s opinion in Soemitro (1973) that:

“The generally accepted goal of fiscal is that of attainment of greater economic stability, that is the maintenance of a reasonably stable rate of economic growth without the development of substantial unemployment in the general price level on the other”.

Taxation Framework

International tax is a term that refers to the international aspects of a country’s tax provisions (Darussalam et al., 2010, p. 2). Conversely, according to Holmes (2007, p. 2), international tax refers to statutory provisions that stipulate cross-border transactions between countries. Rohatgi, (2002, p.1) also argues that international tax refers to global tax provisions that may be applied to transactions between two or more countries across the world, thus, supporting the objectives of the domestic tax system. International tax, in general, stipulates the taxing rights of foreign-sourced income received by resident tax subjects or vice versa.

State sovereignty in tax provisions may differ and conflict with other countries and give rise to mutual claims concerning taxing rights on a tax subject or object. As such, “international tax norms” as generally and internationally prevailing provisions are called for (Darussalam & Septriadi, 2017, p.1). These norms stipulate that a country’s taxation claims may only be implemented based on the basic principles of taxing rights. These basic principles are referred to as the connecting factors.

According to Holmes (2007, p.19), there exist two fundamental principles in determining the taxing rights of a country. These two principles are explained below:

1. Residence Principle. Based on this principle, the right of a state to impose taxes on a person (individual or entity) exists due to “personal attachment”, such as residence, domicile, citizenship, place of establishment, place of management. This principle is also known as the personal connecting factor.

2. Source Principle. Based on this principle, the right of a state to impose taxes on a person (individual or entity) exists due to “economic attachment”, i.e. the presence of economic activities or the tax object is “connected” to the territory of a country. The connection is usually determined based on the following criteria: the location of assets, the location of service provision, the location where a contract is signed, the domicile of the payer of income, or the location where costs are incurred. This principle is also known as the objective connecting factors.

The source-based taxation principle was established in the early 1920s by a study group on the harmonization of the international tax system sponsored by the League of Nations ( Bruins, 1923). The harmonization aims to avoid double taxation in cross-border transactions. To accomplish this goal, the study group formulates four weighting factors as the basis for harmonizing the international tax system, as follows:

1. the origin of wealth or income (origin/source),

2. the legal jurisdiction of wealth and income (site),

3. recognition of rights to wealth and income (enforcement of the rights), and

4. domicile of the entity that holds the wealth or income recipient (residence).

Based on the four factors above, this study group concludes that only the first (source) and last (residence) factors are eligible fundamental principles of the modern international tax system that have survived to this day. The use of the two principles above, however, leads to controversies in the implementation. These controversies may occur in the event of claims from transacting countries.

As with taxes in general, principles that are used as the basis for many countries in formulating international tax policies are inherent in international tax. According to Rohatgi (2002), there are 5 (five) principles of international tax:

1. Equity and Fairness: This principle implies that the tax system must be equitable and fair for taxpayers in that taxpayers with the same income must be subject to the same amount of taxes. In other words, taxes are paid based on the ability to pay. In the international context, tax regulations must enable a country to receive an equitable share of taxes resulting from transactions involving that country. The distribution of taxing rights is based on negotiations or agreements on equal standing and mutual respect for the taxation of each party.

2. Neutrality and Efficiency: Based on this principle, the tax system should not interfere with the market in allocating factors of production efficiently. In other words, economic decision-making should not be influenced by external factors, such as taxes.

3. Promotion of Mutual Economic Relations, Trade, and Investment: Under this principle, the tax system must encourage mutually beneficial economic relations through trade and investment to enable the economies of each country to grow.

4. Prevention of Fiscal Evasion: Through this principle, a tax system must be equipped with the instruments to prevent tax avoidance.

5. Reciprocity: This principle is defined as a condition in which each country with full taxing rights on income derived from said country accepts the existence of tax restrictions only if other countries provide the same treatment.

Double Taxation

Among possible issues due to mutual claims of taxing rights on a cross-border transaction is double taxation. In the context of international tax, double taxation has long been controversial.Double taxation may occur when more than one tax jurisdiction imposes taxes on a cross-border transaction. As specified by Darussalam & Septriadi (2017, p. 8), juridical double taxation refers to a situation where one tax subject is imposed with taxes by more than one country on the same income in the same tax year.

As stated by Surahmat (2005, p.21), there are three conflicts in the juridical double taxation:

1. The conflict between the domicile principle and the source principle: This conflict occurs in the event of cross-border transactions involving two countries that adhere to the domicile principle and the source principle. Taxes on all income earned worldwide will be imposed by countries that adhere to the domicile principle (worldwide income principle), whereas countries applying the source principle only impose taxes on income sourced from their countries.

2. The conflict due to different definitions of “resident tax subjects”: This conflict is caused by different definitions of “resident tax subjects”, in which both individual and corporate taxpayers may be considered as resident tax subjects of the two countries. This condition results in taxpayers being taxed twice. This conflict arises especially in countries that adhere to the citizenship principle as the second criterion in determining whether a person is a resident tax subject of those countries. This conflict, known as dual residence, is found in many individual taxpayers.

3. Different definitions of “sources of income”: If two or more transacting countries treat one type of income as income sourced from their territory, this will lead to a conflict concerning the source of income. Different interpretations concerning the source of income that compels each country to impose taxes on said income contribute to this conflict.

The issue of economic double taxation may also be found in the context of cross-border dividend transactions between subsidiaries and parent companies (intercorporate dividends). In this respect, triple double taxation, a combination of juridical and economic double taxation, may even take place (Koefler, 2012, p. 2).

Elimination of Double Taxation

There are two methods to eliminate double taxation. First, the elimination of double taxation through multilateral or bilateral action. This measure can be undertaken by establishing a Tax Treaty. A Tax Treaty aims to avoid double taxation as indicated by the comments of the OECD and the UN Model (Darussalam & Septriadi, 2017, p. 8).

Juridically, a Tax Treaty seeks to avoid double taxation, whereas economically, it pertains to transfer pricing (Darussalam & Ngantung, 2013, pp. 64-65). A Tax Treaty, however, is only intended to juridically eliminate the impact of double taxation and not to economically eliminate the impact of double taxation (Lang, p. 73).According to Darussalam & Septriadi (2017, p. 9), a Tax Treaty eliminates the impact of double taxation in several steps. In the first step, the Tax Treaty stipulates the allocation of taxing rights as per the type of income to the countries that establish the Tax Treaty. In the second step, the Tax Treaty outlines provisions on the elimination of double taxation in relation to the allocation of taxing rights, i.e. by requiring the residence country to eliminate the taxation that has been claimed by the source country in the first step through a method of eliminating double taxation, in general, the exemption or credit method. In the exemption method, the residence country is obliged not to claim its taxing rights, thus, only the source country may perform such a claim. In the credit method, on the other hand, taxing rights are based on worldwide income in the residence country, and (limited) credit in the amount of taxes claimed in the source country may be provided.

Second, the elimination of double taxation through unilateral measures, i.e. provisions that are applied unilaterally by a country as per its domestic tax provisions. This action may be implemented both by the residence country and the source country. Unilateral efforts by residence countries are carried out by means of exemption, credit, or deduction (Darussalam & Danny Septriadi, 2017, p. 9).

On the other hand, unilateral efforts by source countries are carried out by means of rulings between the tax authorities and taxpayers or other methods to allow legal certainty for non-resident tax subjects wishing to invest in terms of their tax treatment in a country (Thuronyi, 2010, p. 445). In general, however, tax avoidance is unilaterally provided by the country acting as the residence country.

As many countries unilaterally apply double tax avoidance provisions, this raises a debate concerning the degree of importance of a Tax Treaty in eliminating the impact of double taxation. In general, a tax treaty is considered not crucial to eliminate the impact of tax avoidance. Nonetheless, some parties are of the opinion that a Tax Treaty remains required (Darussalam & Septriadi, 2017, p. 10).

The Concept of PEs

The concept of Permanent Establishments (PEs) in the international tax system is based on the principle of geographic and physical connection between the taxpayers and tax authorities. The geographic and physical connection stipulates and limits the tax authorities’ authority to only those taxpayers physically residing within these tax authorities’ jurisdictions (OECD, 2003, pp. 8-9). In other words, the tax authorities are not authorized to collect taxes from taxpayers, whether individuals or companies, that do not physically reside within their jurisdiction.

In the concept of PE, business profits may only be taxed in the residence country of the company, unless the company is closely affiliated with the country where the business profits are earned. This implies that the source country of income cannot tax business profits earned by non-resident tax subjects, without the existence of a PE in the source country of income (Darussalam & Ngantung, 2017, p. 109).

The Concept of PE Based on the Tax Treaty Model.

PEs in the OECD and UN Models, in essence, are similar in the elucidation, i.e. concerning the concept of PE in general as outlined in Article 5 paragraph (1), physical PE as described in Article 5 paragraph (2), and construction PE described in Article 5 paragraph (3) of the OECD Model and Article 5 paragraph (3) subparagraph a of the UN Model.

Pursuant to Article 5 paragraph (1) of the OECD Model and UN Model, PE may be defined as a fixed place of business to perform business activities of a company that is run partially or as a whole. In general, the establishment of a PE must meet the following conditions (Khan, 2000, p. 78):

1. The presence of a place of business (place of business test);

2. Established in a certain location (location test);

3. The tax subject has the right to utilize the place of business (right use test);

4. The use of the place of business is permanent and exceeds a certain period of time (permanent test);

5. Activities carried out through said place of business must constitute business activities as per the definition of business activities stipulated under the domestic as well as the Tax Treaty provisions (business activity test); and

6. In the event that one of the above conditions is not met, no PE will be established.

On the other hand, Article 5 paragraph (2) of the OECD Model and UN Model contains examples of physical PEs or referred to as the ‘positive list’. Included in the ‘positive list’ are

1. A place of management;

2. A branch;

3. An office;

4. A factory;

5. A workshop; and

6. A mine, an oil or gas well, a quarry or any other place of extraction of natural resources.

There are requirements for the establishment of a construction PE in the elucidation of article 5 paragraph (3) of the OECD Model and Article 5 paragraph (3) subparagraph a of the UN Model. The definition of a Construction PE includes a construction project or an installation project. The construction project covers the following:

1. Building construction;

2. Construction of roads, bridges, or irrigation;

3. Renovation of buildings, roads, bridges, or irrigation; and

4. Pipe laying, excavation, and dredging.

However, it should be noted that there are fundamental differences between the Construction PE stipulated under the OECD Model and the UN Model. The basic differences include (Darussalam & Ngantung, 2017, p. 123):

1. In the OECD Model, supervision over a construction or installation project cannot be classified as a PE, whereas in the UN Model, these activities may constitute a construction PE;

2. The establishment of a Construction PE between the OECD Model and the UN Model also differs in terms of the period (“time test”). In the OECD Model, the period should last more than 12 (twelve) months, whereas in the UN Model it lasts 6 (six) months.

Further, Article 5 paragraph (5) of the OECD Model and UN Model outlines another form of PEs, i.e. Agent PEs. The concept of an Agent PE is a PE established due to the presence of representatives of said business entity in the source country. As such, in Agent PEs, a business entity is not required to establish a representative office but may appoint an agency or individual as an agent that represents its interests (Darussalam & Ngantung, 2017, pp. 131-132; OECD, 2003, p. 8- 9; Pinto, 2003, p. 74).

Based on the formulation of Article 5 paragraph (5) and paragraph (6) of the OECD Model and UN Model, the definition of Agent PEs consists of the following elements:

1. The Agent is the person that acts on behalf of the principal (dependent agent);

2. The Person has the authority to sign the contract;

3. The Contract is carried out continuously; and

4. The Person does not constitute an independent agent that acts to carry out his main business activities.

Thus, some testing is required to determine whether or not an agent constitutes a PE.

Unlike the OECD Model, the UN Model outlines PEs in the form of Service PEs under Article 5 paragraph (3) subparagraph b of the UN Model. Based on the formulation of this article, in terms of the provision of services within this definition, consulting services by a company in a country may constitute a PE in said country insofar as the services are provided (for the same or related projects) exceeding the period agreed in the Tax Treaty, i.e. more than a period of 6 (six) months within a period of 12 (twelve) months. (Darussalam and Ngantung, 2017, p. 126).

The Concept of International Tax Avoidance

In the context of international tax, various schemes may be implemented by multinational companies to perform tax savings (Darussalam & Septriadi, 2009). Vann in a book by Thuronyi as quoted by Gunadi (2007, p. 277) mentions several international tax avoidance techniques, including:

1. Transfer Pricing, which constitutes a profit-sharing instrument between companies in a multinational group of companies. In other words, transfer pricing is a technique in which transaction prices between companies in a group located in different countries are regulated by shifting profits to another company in a group located in a country with a low tax rate resulting in minimum total taxes paid as a group. Transactions in the group may take the form of transfers of goods or services, interest on loans, royalties, production engineering (toll manufacturing, contract manufacturing), allocation of overhead costs, administrative and management costs, cost-sharing, cost funding arrangements, and commercial engineering. (reinvoicing companies, loss-making companies, letterbox companies, and special purpose vehicle companies);

2. Thin capitalization, a technique of financing a branch or subsidiary with interest-bearing debt rather than using share capital. This technique involves avoiding the use of large capital and choosing branch financing using loans, thus, the interest expenses may serve as tax deductions;

3. Modern financial instruments. In addition to contributing tax problems in terms of the authenticity of loans (direct and indirect loans or capital), funding companies with loans lead to companies seeking other techniques to avoid taxes, i.e. by utilizing modern financial instruments and involving tax haven countries. This tax avoidance technique generally targets developing countries where the regulations concerning financial instruments are not clearly regulated. Several forms of commonly used modern financial instruments include non-interest bearing loans, interest swaps, exchange rate swaps, derivatives with underlying debt and receivables, structured finance contracts on import and export transactions, zero-coupon bonds, issuance of debt securities through SPV companies in tax haven countries;

4. Payments to or through companies in tax havens. A tax haven country refers to a country or region that imposes low or no taxes and provides a safe place for deposits to attract capital. Several transactions that go through tax haven countries include transfer pricing, captive insurance companies, captive banking, shipping under a tax haven flag, back-to-back loans and parallel loans, establishing holding companies, and licensing companies;

5. Double dipping. Double dipping constitutes an alternative technique to simultaneously reduce the tax burden in the source and residence countries, i.e. a technique that simultaneously reduces taxes in the source and residence countries by doubling the use of favorable tax provisions in both countries. This technique can be undertaken in two ways. First, by taking advantage of differences in tax treatment on the same transaction between the residence country and the source country. Second, by utilizing dual residence, in which several countries treat the consolidated profits and losses of several companies that are under joint ownership;

6. Treaty Shopping. Thuronyi explains that treaty shopping is a practice conducted by a taxpayer of a country that does not have a tax treaty and establishes a subsidiary in a country that has a tax treaty. Subsequently, the taxpayer performs investments through the subsidiary and, thus, the investors may enjoy low tax rates and other tax facilities listed in the tax treaty. Treaty shopping may also refer to the utilization of a tax treaty by establishing a conduit company in one of the tax treaty partner countries by non-residents (resident tax subjects) from the two tax treaty partner countries;

7. Domicile shifting, a technique of shifting the tax domicile from a country with higher tax rates or one that applies global taxation to a country with lower tax rates or one that applies territorial taxation;

8. Shifting source or location of income, i.e. a technique of not repatriating foreign-sourced income to within the country using a subsidiary deliberately established in a tax haven country to accommodate the foreign-sourced income;

9. Combination of several avoidance techniques;

10. Hybrid entity, a technique of utilizing the legal form of a company in which a company is considered a corporation in one country and a partnership in another, thus, subject to different tax treatments.

Other prevalent tax avoidance schemes nowadays are as follows:

Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements

Hybrid mismatch arrangements emerge where two countries disagree on the classification or characterization of several terms of regulations with fundamental effects on income tax objectives (Haris, 2015, p. 189). The intercountry mismatch may result in double taxation or the opposite, double non-taxation. Differences in provisions are subsequently abused by tax evaders to minimize their fiscal obligations (Tambunan, 2016, p. 26).

The tax benefits from the hybrid mismatch arrangement scheme are as follows:

1. Double deduction scheme, a rule whereby income deductions (cost recognition) for tax purposes are carried out in two different countries.

2. Deduction or no inclusion scheme, a rule that results in the recognition of costs in one country, generally considered as interest costs, but not recognized as income in another country.

3. Foreign tax credit generators, i.e. taking advantage of a situation in which entities in a country, based on existing provisions, receive foreign tax credits that they are not entitled to. The foreign tax credit generator scheme is established through the use of hybrid transfers of equity instruments. This may be caused by a share sale and repurchase agreement (repurchase agreement) which is treated as a sale and repo of shares in one country, but as a loan with shares as collateral of assets in another country.

Transfer Pricing Manipulation

Transfer pricing manipulation is the most widely practiced tax avoidance scheme. Unsurprisingly, the OECD-G20 reviews transfer pricing in 4 action Base Erosion and Profit Shifting plans out of a total of 15 action plans, the most among other issues. (Septriadi, 2019). Transfer pricing manipulation can be defined as the activity of setting transfer prices to be too high or too low to reduce the amount of tax payables. The following is an example of the use of a transfer pricing scheme in tax avoidance as explained by (Darussalam et al., 2013, p. 16).

For example, XCo, a manufacturing company established and domiciled in State A, sells goods to its affiliated company, YCo, which is established and domiciled in State B. XCo can reduce its tax burden by performing transfer pricing for the goods it sells to YCo. The undertaken transfer pricing scheme can reduce the total tax burden of the multinational group of companies, XCo and YCo if:

1. The tax rates in State B are lower than those in State A;

2. State B is classified as a tax haven country (a country with low tax rates and information confidentiality;

3. Even though the tax rates in State B are higher than the tax rates in State A, transfer pricing may still be conducted in the event of losses by YCo or loopholes that can be exploited in State B.

Avoidance of Permanent Establishment (PE) Status

Determining the taxing rights on business profits depends on the requirements of the establishment of a PE. In the absence of a PE, the source country cannot impose taxes on business profits earned by non-resident tax subjects sourced in said country (Dhora, 2016, p. 60).

Controlled Foreign Company (CFC)

In most countries, the worldwide income principle applies to all tax subjects, both on domestic-sourced and foreign-sourced income. In contrast, non-resident tax subjects are only subject to taxes on income originating from the source country of income.

For example, Company A, a resident tax subject in State D establishes a subsidiary (for example, Company B) in State S. Next, in State S, Company B carries out its business and receives income. Based on the generally prevailing provisions, in addition to being taxed in State S as the source country of income, the income received by Company B in State S will also be taxed in State R when Company B distributes its income (dividends) to Company A as its shareholder. This is because, in taxes, Company A and Company B are considered two separate entities.

The condition Company A and Company B are in can be deemed to constitute economic double taxation as the same income is taxed more than once on two different tax subjects. This may be detrimental to Company A as the parent company. Therefore, to avoid being taxed at the parent company level, Company A then arranges for Company B to postpone the distribution of income in the form of dividends or retain the earnings in its subsidiary company (Company B). By retaining income in the form of dividends at Company B in State S, the income in the form of dividends cannot be taxed in State R.

Based on the above example, it can be concluded that control over a subsidiary established in another country (foreign subsidiary) is exercised by its shareholders. This scheme is known as “controlled foreign company” (CFC) and is widely used by multinational companies to avoid taxation in the residence country of the parent company so as to maximally “save taxes”, both in the residence country of the parent company and in the residence country of the subsidiary.

Methodology

This study employs qualitative research methods. According to Cresswel (2010), qualitative research refers to research that aims to understand human or social problems based on a holistic picture, a series of words and sentences and informants’ reports carried out in natural settings or conditions. This is in line with Stake’s (2005) opinion that qualitative research aims to reveal the distinctiveness or uniqueness (dynamics) of the characteristics in the case under study. As such, the emphasis is on the continuous changes in observed variables in this study. Qualitative research enables researchers to see the world through the eyes of researchers or participants (Greener, 2008).

Data analysis is performed using the Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS), i.e. NVivo 12. NVivo is a qualitative data analysis software created by Tom Richards and further developed by Qualitative Solutions and Research (QSR) International. QSR is the first company to develop qualitative data analysis software (Bazeley, 2007). The underlying consideration in using NVivo as an analytical tool in this research is Nvivo’s superiority in supporting qualitative analysis. The use of NVivo may increase visibility and transparency in the research process as well as perceptions of a more scientific research process (Atherton & Elsmore, 2007).

Results and Discussions

Based on the research results, three forms of tax avoidance schemes are found, as follows: (1) avoiding the establishment of a Permanent Establishment (PE) in the source country, which is further divided into three schemes, i.e. avoiding physical presence in the source country, business fragmentation, and carrying out the preparatory and auxiliary functions in the source country, as well as using countries with low tax rates; (2) utilizing payment schemes through foreign media or platforms; and (3) through Transfer Pricing with the Cost Contribution Agreement scheme.

Tax Avoidance Scheme by Avoiding the Establishment of a Permanent Establishment in the Source Country

Similar to international practice and as stipulated in the Tax Treaty signed by between Indonesia and its partner countries, business profits of a foreign company in Indonesia may only be taxed if said company has a PE in Indonesia. In other words, without a PE, Indonesia does not have the taxing rights on these profits. However, similar to the generally accepted PE concept, under the Tax Treaties between Indonesia and its partner countries, PE may be established in the source country only if a foreign company has a physical presence in that country. This is also a loophole that may result in the loss of the tax base of cross-border digital transactions in Indonesia.

Tax Avoidance Scheme by Avoiding Physical Presence in the Source Country

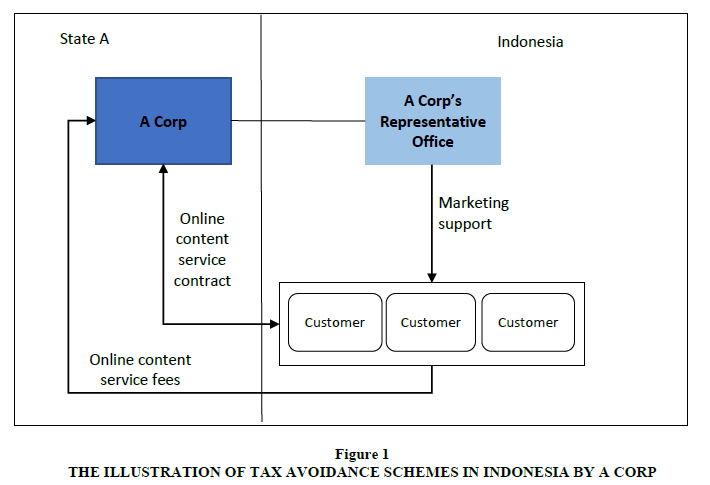

A tax avoidance scheme of exploiting loopholes in the definition of PEs is carried out by A Corp, a digital company providing online content services in the Asia Pacific region, including Indonesia. A Corp is not domiciled in Indonesia and is a resident tax subject in State A. To carry out its business in Indonesia, A Corp has established a representative office in one of the major cities in Indonesia. This representative office has the status of an Indonesian legal entity and is registered at one of the Tax Offices (KPP) with the status of Foreign Investment (PMA).

All requests for online content services from a customer in Indonesia will be handled directly by A Corp in State A. Contract establishment, pricing, and contract closure are all performed online between A Corp and the customer. The representative office is only tasked with providing information to the consumer about advertising services that may be provided by A Corp. In other words, the representative office only performs the marketing function.

Next, all income originating from online content service contracts with Indonesian customers will be directly received by A Corp. Concurrently, the representative office will receive remuneration from A Corp for the marketing functions it carries out in Indonesia.

Below is an illustration of the business carried out by A Corp in Indonesia(Figure 1).

Since State A and Indonesia have established a Tax Treaty in which A Corp is the resident recipient, the determination of taxing rights will refer to the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A. Why so?

This is because as per Article 32A of the Income Tax Law, where there is a Tax Treaty with a counterparty residence country, the Tax Treaty position will apply. This implies that the stipulation of the tax treatment on income from digital transactions in the form of online content services received by A Corp in Indonesia will refer to the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A. Next, in the event of a conflict of rules between the Tax Treaty and the Income Tax Law, the Tax Treaty provisions shall supersede the provisions under the Income Tax Law. The following is the formulation of Article 32A of the Income Tax Law concerning the above.

“To improve economic and trade relations with other countries, a lex-specialis instrument that stipulates the taxing rights of each country to provide legal certainty and avoid double taxation and prevent tax evasion. The forms and materials thereto refer to international conventions and other provisions as well as the national tax provisions of each country.”

Under the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A, taxation of A Corp’s income refers to Article 7 concerning business profits. Based on the formulation of Article 7 of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A, the business profits received by A Corp from providing online content services in Indonesia will only be taxed in State A, unless A Corp runs its business in Indonesia through a PE in Indonesia. The question is, does A Corp have a PE in Indonesia?

The issue of tax avoidance subsequently arises as referring to the business structure and transactions that A Corp carries out, it can be assumed that A Corp exploits a loophole in the provisions on PE establishment to avoid the establishment of a PE in Indonesia. Similar to the PE concept in general, the physical presence in the source country must be met for a PE to be established pursuant to the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A. PE establishment in Indonesia is avoided in the following methods:

1. A Corp establishes a parent company in State A to enable A Corp to take advantage of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A as the basis for not constituting a PE in Indonesia.

2. A Corp avoids physical presence in Indonesia by not establishing an office in Indonesia. A Corp only has a representative office in Indonesia and said office only carries out the marketing function, and based on Article 5 paragraph (3) of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A, this function constitutes an auxiliary function, thus, does not constitute a PE in Indonesia. The following is the formulation of Article 5 paragraph (3) of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A.

The term "permanent establishment" shall not be deemed to include:…

The maintenance of a fixed place of business solely for the purpose of advertising, for the supply of information, for scientific research or for similar activities which have a preparatory or auxiliary character, for the enterprise.

Based on the above article, it can be concluded that the function of the A Corp’s representative office in Indonesia does not result in a PE in Indonesia. This is because the representative office functions as marketing support for A Corp’s business activities in Indonesia, and these activities are exempted from the definition of PEs based on the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A.

A Corp also avoids physical presence in Indonesia by directly establishing online content service contracts between A Corp and Indonesian customers online. By arranging contracts online and not giving the representative office the authority to close the contract, A Corp avoids the establishment of an Agent PE. In line with the OECD (2015, pp. 10-21) Agent PEs are established if they are authorized to establish agreements.

Referring to the above explanation, it may be argued that several loopholes in the provisions under Article 5 of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A are exploited by A Corp to avoid the establishment of a PE in Indonesia. First, Article 5 paragraphs (1) and (2) concerning the physical establishment of PEs. Second, Article 5 paragraph (3) concerning the provisions on exemptions from PEs. Third, Article 5 paragraph (5) concerning Agent PEs. A Corp can take advantage of these loopholes because the establishment of PEs in the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State A is still based on the traditional economy (brick and mortar). As such, it does not accommodate the digital business model undertaken by A Corp. A Corp easily avoids the establishment of PEs through such modern business activities. The provisions on PE exemptions under Article 5 paragraph (4) of the OECD Model become regulatory loopholes for the digital business model (Darussalam and Yusuf W. Ngantung, 2017, p. 169).

Tax Avoidance Schemes by Performing Preparatory and Auxiliary Functions in the Source Country and Using Countries with Low Tax Rates

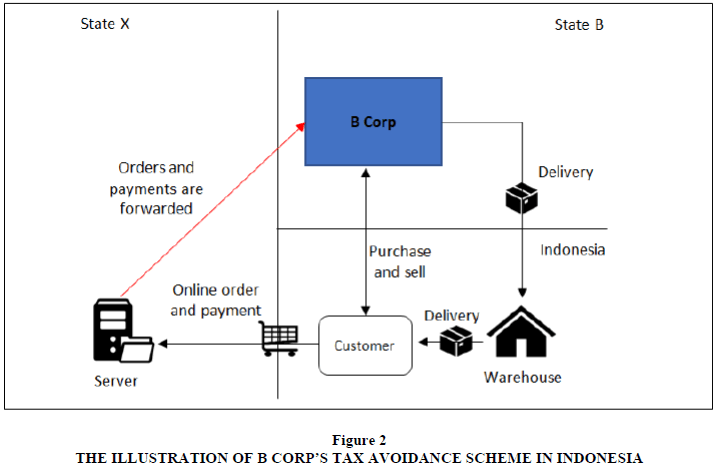

Countries or jurisdictions with low tax rates are increasingly being used, specifically, in digital business models. B Corp, a multinational enterprise (MNE) in State B engaged in selling goods online, also employs this method. The products offered by B Corp are displayed through a website and customers are allowed to acquire these products online by payment via credit card. Physical products are to be delivered via independent courier services, whereas digital products can be downloaded from B Corp’s website.

In selling its products throughout Asia Pacific countries, including Indonesia, B Corp uses a server placed in State X, a country with low tax rates. All goods orders and payments are made online through B Corp’s website and processed through this server. Next, the order data and information will be sent to the parent company in State B for further processing. Physical products are directly delivered by B Corp to the customer. Therefore, to support its business processes, B Corp establishes a warehouse in Indonesia as temporary storage before its products are sent to customers.

The warehouse is a simple building used as a temporary storage area. In the warehouse, a number of workers record the entry and release of goods. These workers, however, are not B Corp’s employees but casual workers receiving monthly wages. An illustration of this case can be seen in the following image(Figure 2).

Referring to the illustration of transactions carried out by B Corp in Indonesia, it can be concluded that B Corp is pursuing a strategy to avoid the establishment of a PE in Indonesia in two ways.

First, by placing a server with a significant function in State X. State X is chosen as State X imposes taxes at low rates, thus, where there is a PE in said country, the effect is not significant for B Corp. In such an event, the existence of the server has established a B Corp PE in State X. This is based on the OECD’s statement that there are several conditions for a server to constitute a PE. The following is the explanation. The server on which the website is run and its location must reside and belongs to an overseas company/leased and operated by the company and does not constitute a web hosting company. In such case, B Corp’s server is in State X, belongs to, and is operated by B Corp itself. This server is not a web hosting either.The server must be in the taxing state. The server is in State X, a country with low tax rates. Core business must be carried out through the server, thus, the server does not serve a preparatory or auxiliary function, without the need for human intervention. It can be said that B Corp’s core business is carried out through the server because all orders and payments from customers are processed through this server. Without a server, it is impossible for B Corp to carry out its business as a company that sells digital goods and products online.

Second, the physical presence of B Corp in Indonesia is only a building with a function to store B Corp’s products before they are sent to customers. The warehouse does not constitute a B Corp PE in Indonesia as based on Article 5 paragraph (3) of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State B, it is exempted. Notwithstanding paragraphs (1) and (2), a permanent establishment shall not be deemed to exist by reason of one or more of the following:

The use of facilities solely for the purpose of storage or display of goods or merchandise belonging to the resident;…

Upon further examination, however, the warehouse is not insignificant. For B Corp’s business, the warehouse, in essence, plays an important role and similar to the server, is included as B Corp’s core business activities. Without the warehouse, B Corp is bound to experience difficulties in carrying out its business.

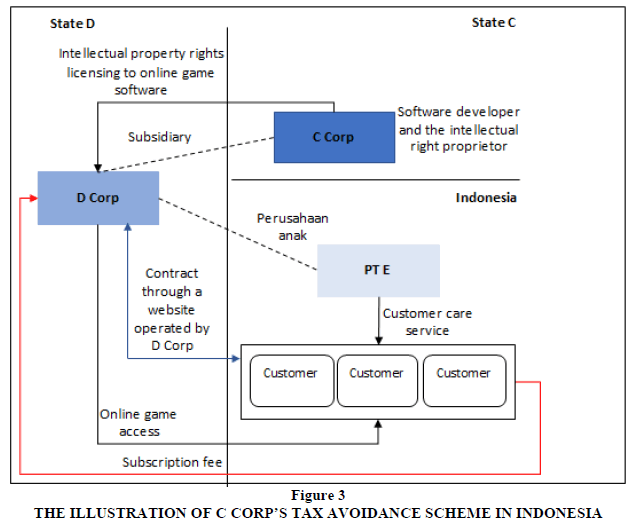

Tax Avoidance Scheme with Business Fragmentation

Business fragmentation is currently among the widely employed schemes by multinational companies, including companies that carry out digital cross-border transactions. With this scheme, companies can minimize their tax burden. In fact, in some cases, they simultaneously avoid taxation in various countries. The practice of business fragmentation by companies engaged in digital transactions, as conducted by C Corp, seeks to avoid taxation in Indonesia(Figure 3).

C Corp is a State C multinational company engaged in cloud computing that develops software in the form of online games. C Corp operates worldwide by providing paid online games to its customers in exchange for a subscription fee. The software used in the online games, along with all the technologies related to payment processing and customer data security, is developed by C Corp’s employees of State C.

On another note, C Corp also conducts marketing and sales coordination in various regions in State C using a website to minimize costs, maintain sales consistency, and increase efficiency. C Corp grants the right to use the cloud computing-related software and knowledge to various regional subsidiaries through licensing and sub-licensing agreements, among others to D Corp, a subsidiary in State D.

D Corp functions to regulate the provision of online game access to customers in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia. The subsidiary also hires a large number of employees to operate a website used to sell access to online games developed by C Corp for all customers residing in Southeast Asia.

All online game subscription contracts will be entered into online by customers in Southeast Asia via a website operated by D Corp in State D. All contract standards and contents, however, are stipulated by C Corp as the parent company. On the other hand, all major data center controls to run online game software, customer transaction processing, and customer data storage originating from Southeast Asia, including in Indonesia, are also run by D Corp. The promotion and marketing are also carried out by D Corp through the website it operates in State D.

Considering that Indonesia constitutes one of the significant markets for C Corp’s business, D Corp subsequently establishes a subsidiary in Indonesia, i.e. PT E. In Indonesia, PT E only provides customer care services for Indonesian customers. In connection with this task, PT E will receive compensation calculated using the cost plus method. Referring to the above illustration and explanation, it can be inferred that the tax avoidance scheme practiced by C Corp in Indonesia includes fragmenting its business into several small-scale businesses, thus, the business carried out by C Corp is only limited to auxiliary activities. In this case, the auxiliary activities take the form of customer care services for customers in Indonesia. Under Article 5 paragraph (3) of the Tax Treaty between Indonesia and State C, activities that solely support the fixed place of business cannot be deemed to constitute a PE.

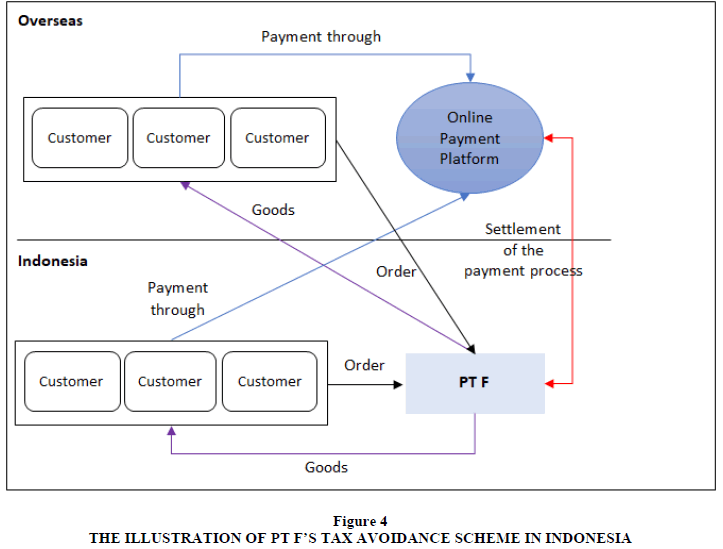

Tax Avoidance Schemes by Utilizing Payment Schemes through Overseas Media or Platforms

Tax avoidance schemes of utilizing payment schemes through unregistered overseas media or platforms are carried out by PT F. PT F is a company with the Indonesian resident tax subject status that conducts transactions locally and internationally. To simplify and expedite its transactions, PT F provides several alternative payment systems, among others, the payment system through overseas media or platforms. This payment system is specifically intended for transactions between PT F and PT F’s customers outside Indonesia. In practice, however, the overseas media or platforms employed by PT F as the payment instrument provider are not yet registered in Indonesia.

The explanation on the flow of transactions to the payment process that occurs in PT F’s business is as follows:

1. The customer places orders of goods on PT F’s website and chooses a payment system through overseas media or platforms.

2. PT F receives order details along with information about the payment system chosen by the customer.

3. PT F forwards the payment information online to the overseas platform as a third party for verification. Once the payment is verified, PT F will receive reports from the platform online.

PT F subsequently forwards the information that the payment has been successful to the customer and processes the delivery of the goods. The following is an illustration of the above explanation in Figure 4.

As the foreign media or platforms used in PT F’s payment system are not registered in Indonesia, these payments are not supervised. This implies that the amount of transactions performed by PT F and payments received by PT F through this method or platform are not monitored. Next, due to the absence of such supervision, to minimize the tax burden that must be paid, PT F may not record all transactions for which the payments are made via foreign platforms. This tax avoidance scheme will also be easier to implement if the customers transacting with PT F are abroad.

Tax Avoidance Practices Scheme through Transfer Pricing with the Cost Contribution Agreement Scheme

One of the methods to transfer ownership of an IP or other intangible asset is through the cost contribution arrangement (CCA) as has been done by PT G, a cloud computing company with the status of an Indonesian resident tax subject. A cloud computing company, PT G has successfully produced software used to edit images and videos. The first software was developed by PT G in 2000. Along with the development of the license agreement for both the domestic and overseas use of PT G’s software, PT G receives more income in the form of royalties.

In light of this fact, PT G estimates that with the level of income tax rates in Indonesia, the tax burden to be borne by PT G is greater. Ultimately, PT G decides to transfer ownership of the software to its subsidiary (H Corp) which is located in a tax haven country through the cost contribution arrangement (CCA). This transfer seeks to shift income in the form of royalties from the use of the software from Indonesia to a tax haven country, thus, resulting in a lower tax burden.

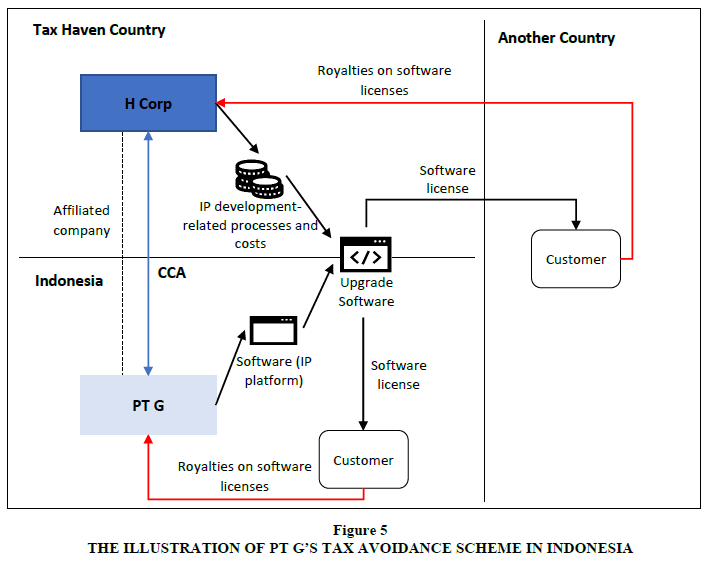

Under CCA, the software approved for joint development with H Corp is the software developed by PT G in 2000 (IP platform/existing IP platform). CCA therein also agrees that H Corp acts as the party performing research and development responsible for all costs incurred from the software development process. In further detail, Figure 5 depicts an illustration of the tax avoidance scheme carried out by PT G in Indonesia.

Based on the analysis of functions, assets, and risks on the respective contributions of PT G and H Corp under the CCA, it is evident that the value of the contribution made by H Corp in software development is considered greater than that of PT G. Consequently, for the developed software, PT G is “only” entitled to benefit from the use of the software in Indonesia. Conversely, the value of benefits over the use of software from other countries worldwide belongs to H Corp. In other words, under the CCA, PT G is only entitled to receive royalties on software licenses originating from Indonesia. Royalties arising from worldwide software licenses, on the other hand, belong to H Corp.

It should be noted that to reflect the share of economic ownership of the newly developed software, no royalties are paid between PT G and H Corp. PT G, however, will receive buy-in payments (similar to periodic inter-company royalties or lump sum advance payments) from H Corp in connection with PT G’s contribution in providing the software as the developed “base material”.

Based on the foregoing, arguably, through CCA, ownership of the software which was originally under PT G, has been largely transferred to H Corp. Consequently, income in the form of royalties on the license to which “only” PT G was originally entitled to, as per the CCA arrangement, is largely the right of H Corp. In this regard, PT G is only entitled to receive royalties originating from the granting of software licenses in Indonesia. As a result, PT G can minimize taxation in Indonesia and the company’s overall global tax liability will decrease.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis results, concerning the research on “Tax Avoidance Schemes in Cross-Border Digital Transactions in Indonesia”, it can be concluded that the tax avoidance schemes are carried out as follows: Business actors take advantage of loopholes and flaws in regulations on the stipulation of PE, including avoiding physical presence, utilizing preparatory and auxiliary functions, and conducting business fragmentation. These schemes lead to the Indonesian tax authorities’ inability to tax the income earned by these business actors.

Business actors take advantage of payment media that are difficult for the Indonesian tax authorities to detect. These schemes result in difficulties in recording tax transactions, thus, taxation potentials, both from transactions or income taxes from entrepreneurs and platform providers, are reduced.

Business actors employ the cost contribution agreement scheme with a larger contribution sharing arrangement for the subsidiary compared to the parent company.

References

Bazeley, P. (2007). Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. SAGE Publications.

Darussalam dan Ngantung. (2013). dalam buku “Transfer Pricing Ide Strategi dan Panduan Praktis dalam Perspektif Pajak Internasional” Editor Darussalam, Septriadi, D. Kristiaji, B. Bawono. Jakarta. DDTC.

Greener, S. (2008). Business Research Methods. Ventus Publishing ApS.

Holmes, K. (2007). International Tax Policy and Double Tax Treaties - An Introduction to Principles and Application. IBFD.

Kofler, G. (2012). “Indirect Credit versus Exemption: Double Taxation Relief for Intercompany Distributions,” Bulletin for International Taxation, 66(2).

Nugroho, A. (2006). E-Commerce Memahami Perdagangan Modern di Dunia Maya. Informatika, Bandung, 3.

OECD. (2003). Articles Of The Model Convention With Respect To Taxes On Income And On Capital Retrieved From Http://www.Oecd.Org/Tax/Treaties/1914467.Pdf.

Rohatgi, R. (2002). Basic International Taxation, London.The Hague.New York : Kluwer Law International

Soemitro, R. (1973). “Pajak Sebagai Alat Kebijakan Fiskal Dalam Hubungannya Dengan Pembangunan Nasional” (Pidato Pengukuhan sebagai Guru Besar dalam Ilmu Hukum Pajak, pada Fakultas Hukum Universitas Padjadjaran tanggal 30 Juni 1973).

Stake, R.E. (2005). Qualitative Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 443-466). SAGE Publication.