Case Reports: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 2

Swap.Com as a Social Style Platform Brand: Strategic use of Social Media Brand Communities

Shelby Chapman, University of Southern Indiana

Amber Hilton, University of Southern Indiana

Arsenio Ward, University of Southern Indiana

Darryl Saull, Purdue University

Curt Gilstrap, University of Southern Indiana

Abstract

The primary subject matter of this case follows the Social Style Platform (SSP) brand Swap.com and its success with social commerce (s-commerce) and value co-creation while entering the social style application market. Secondary issues examined include SSP brands, strategic social media, target audiences, marketing and advertisements, Social Media Brand Communities (SMBC’s), as well as consumer trends impacting SSP brands in the current market. This case has the difficulty level of five and six, appropriate for first- and second-year graduate students and digital marketers in training. The case is designed to be taught in 2 hours and is expected to require 2 hours of outside preparation by students.

Keywords

Swap.com, Social Style Platforms, Social Media Brand Communities, Strategic Social Media

Case Synopsis

Swap.com is a Social Style Platform (SSP) brand launched in 2013 that has shown significant revenue and consumer growth despite the organization’s late entry into the saturated social style market. This case study explores how Swap.com infiltrated the market with competition from fellow SSPs like Poshmark and ThredUP. Additionally, Swap.com’s strategy of leveraging social media, in particular Social Media Brand Communities (SMBC’s) and s-commerce, is discussed. While the popularity of online shopping continues to grow, it is imperative that organizations such as Swap.com stay abreast of the evolving landscape of social media by encouraging value co-creation within SMBCs. Also, identifying target audiences and understanding their motivations to engage on social media provides marketers the tools needed to manage future strategic challenges related to the increased importance of the competitive s-commerce arena.

Introduction

Every year in the United States 14 millions tons of discarded clothing end up in landfills, a stark contrast to the average individual American’s 80 pounds worth of yearly disposed of textiles (Wicker, 2016). With the opportunity to reuse, reduce and recycle, an emerging need to conserve formed the idea behind Swap.com. (2016). This SSP is an online consignment shop specializing in secondhand clothing for women, men, children and babies, and offering non-apparel items such as toys, books, movies and décor.

Prior to an acquisition in 2012 by a European business, Swap.com was known as SwapTree, and focused consignment offerings on items such as books, movies and video games. Lacking a presence in the U.S. market and attracted to a simple swapping business model, European Netcycler purchased SwapTree Kirsner & Lomas (2012). Re-launched in 2013, Netcycler rebranded SwapTree as Swap.com and expanded item categories as well as community development.

A thriving and successful social style platform, Swap.com uses unique branding, logistics, and social media presence to reach online community members. Operating within a traditional retail model while retaining a consignment business structure, Swap.com allows users to ship consignment items to their warehouse. The items are added to the Swap.com platform and offered for sale online. When items are purchased, original sellers are paid. Users can offer clothing from any fashion brand and a wide variety of general items (Perez, 2014).

Notably, the business encourages users to take advantage of their “Swapping” feature – the platform allows consumers to use their account funds, or consignment items, to ‘swap’ for items listed by fellow users. This unique feature differentiate Swap.com from SSP competitors such as Poshmark, which only accepts high end clothing, and ThredUp, which has a different user payment policy upon receiving items (Perez, 2014). Swap.com claims to have “simplified the entire process for buyers and sellers with its logistics center and proprietary technology” (Swap.com, 2016).

Style APP Communities

Various social media platforms provide diverse target audiences for SSP brands to tap into, and it is vital for SSPs to build Social Media Brand Communities (SMBCs) for the continuous drive to expand consumer bases. After Swap.com’s acquisition, the firm’s target audience shifted to parents who search for consignment items specifically for children. Users of the site increased through 2015, and the company added women’s apparel and accessories to their consignment offerings. Rated as one of the fastest growing apparel websites for women’s clothing by Internet Retailer (Swap.com, n.d.) While continuing to diversify offerings, Swap.com added men’s clothing and accessories to the platform in 2016.

Swap.com’s userbase consists of young and middle-aged women who are shopping for children’s and women’s products. While Swap.com provides items for men, the target audience remains focused on parents, and additional shoppers who are searching for a wide selection of affordable, upscale brands that are hard to find elsewhere. One of the first messages that shoppers read on Swap.com’s website (https://www.swap.com/) offers the mission behind the organization: “We enable a community of thrifters to find affordable, quality secondhand apparel for the whole family. Being an online thrift store, we make it easier than ever to filter through like-new, pre-owned clothing. Together we keep millions of items out of landfills which is something everyone can feel good about.”

Considering the relation of SMBCs to Swap.com’s triumph in the s-commerce market, evidence of symbolic exchange can be found through their large community of thrifters. Shifts in generational shopping preferences with younger consumers gravitating toward interactive or visual content, and shopping via Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook, are fueling success in the s-commerce space (Wallace & Wertz 2019). For instance, the integration of in-app shopping features across Instagram and Facebook give brands the opportunity to capitalize on increasing multi-generational interest through visual content and community conversations emerging around the content (Boardman, et al. 2019). Contrasted to other SSPs, Swap.com attributes success to their large online consumer communities and unique target audiences in the s-commerce market.

Consumer Trends and Social Commerce

The rise of social media has led to a dramatic shift towards interactive digital communication relative to consumptive patterns. A recent study found that 73% of Americans regularly use social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. Consequently, 50% of online shoppers indicate they use direct purchase options on social platforms occasionally or regularly (Kunst, 2018). Social sharing across platforms have seen steady growth of various forms of user-generated content such as news, photos, and videos, all made public across individual and community networks. In July 2011, Facebook globally registered more than 750 million active users, with half of them logging on to the site daily (Khang et al. 2012). That number is now 2.5 billion monthly active users, any many use Facebook marketplace among other s-commerce spaces (Facebook, 2020) Social media trends have likewise transferred into other areas of everyday life such as academia and professional practice and, specifically, infiltrated online advertising and marketing with user-generated content; social media platforms have enriched strategies through evolving consumer trends, growing digital brand communities, and ever-increasing social purchase behaviors.

Consumer shopping trends seem to follow social platform adoption and advancements. Previously, consumers 1) ordered products from newspapers, magazines, and catalogues, 2) purchased items from radio shows or televised shopping channels and informercials using telephony, or 3) secured products and services from individual websites. In the age of the internet, shopping online has picked up speed with e-commerce platforms like Amazon.com and Ebay.com offering global spaces to buy and sell products and services. More recent shifts in consumer culture may be credited to social platform availability and adoption as social networks are widely installed and accessed as apps on mobile devices. Today, consumers scroll through social media feeds and commonly view advertisements in and between posts created and shared by friends and family. Platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest, for further example, have direct purchase options that automatically add the service or product to a consumer’s digital shopping cart on the merchant website for purchase with a single click.

Established corporate presences on social platforms allow brands to connect with global audiences in regularly visited spaces to increase brand familiarity and community support through continual exposure (Tsimonis & Dimitriadis 2014). Swap.com and other SSP brands have tapped into this shift in consumer trends to tackle the stigma of purchasing pre-owned clothing, and make secondhand clothing widely available through the use of the e-commerce and social platforms. Shoppers on these platforms participate in collaborative consumption—an action motivated by economic gain, enjoyment, and sustainability (Hamari et al. 2016). The growing trend of consignment shopping also impacts social commerce (s-commerce), a phenomenon consisting of business transactions coupled with social media platform activities driving consumptive practices (Lam et al. 2014). These social interactions and user activities create larger conversations about products and experiences; likewise, these social engagements impact the value, reputation, and awareness of brands about which consumers are talking (Pentina et al. 2013); Zhang (2014) The integration of social media tools into e-commerce platforms (and vice versa) enables consumers to connect and collaborate with one another, generate narrative content, and share products or service reviews Huang & Benyoucef (2013); Lam et al. (2019).

Social Media Brand Communities

Increasing numbers of SMBCs closely parallel the overall usage trends of social media. A brand community is a “specialized, non-geographically bound community, based on a structured set of social relations among admirers of a brand” (Sorensen, et al. 2017). Accordingly, SMBCs are collectives initiated on socially-focused digital platforms. Social platforms are an ideal environment for building brand communities as they offer multiple benefits for organizations that properly use SMBCs due to the affordances of scaled or granular conversations, myriad engagement offerings, and a plurality of dynamic media used to display branded logos and share community members’ uses of and perspectives on brand products or services. Taking advantage of these capabilities, several brand firms now use social networking sites to support the creation and development of brand communities both in population growth and support, as well as through the offering of free and inexpensive branded material (Habibi, et al. 2012).

One of these firms, Swap.com organically leverages social media to create SMBCs and increases the firm’s brand development by sharing information and branded material that perpetuates the history and culture of the brand, and providing assistance to consumer communities to perpetuate or share brand-based posts. Brand communities also provide social structure to customer-marketer relationships and greatly influence customer loyalty (Habibi et al. 2012). An example of how SMBCs generate customer-marketer relationships is identified through customers’ personal social posts through the tagging/mentioning of a brand in recognition of a product or service received. An example of this is observed with the #Swaphowyoushop hashtag when Swap.com users tag their swaps or purchases using the Swap.com moniker. When a brand is mentioned in a SMBC user’s social media post, other community members in that user’s network unfamiliar with the brand may interact with/see the post, thus increasing reach and awareness of the brand. Additionally, this sharing activity may also bring additional members into the SMBC fold relative to the brand as they begin symbolically sharing and engaging with social posts. And while SMBCs communicate brand elements to new members and play an important role in generating relationship marketing with higher efficiency (Habibi et al. 2014), brands must also build and sustian relationships with customers across social networks to truly develop and sustain SMBC support for their brands.

Value creation is a major part of the interaction between brands and SMBCs. Value creation is any process that creates outputs more valuable than its inputs; a marketing concept based upon advertising-to-consumption process efficiency. Value creation is the primary aim of any business entity: Create value for customers who will then purchase or share brand products or services, further brand recognition, and add stability to brand communities. Value creation will also lead to the co-creation of value – the relational concordance of consumer and brand voices converging and communicating in various ways to generate a brand value worth more than it was prior to the concordance (Kim & Choi 2019). Importantly, SSP brands that facilitate social media value co-creation authorize their brand communities to work within stakeholder networks to generate brand perceptions, consumptive practices, and ongoing brand value-building both within and beyond the reach of social networks by talking about SSP brands loudly and innovatively (Zadeh et al. 2019).

Co-creation is a valuable aspect of SMBCs for brands as the activity offers a high return on smaller financial investment because it is often, largely consumer-generated content. There are four categories of symbolic practices through which customers co-create value in brand communities (Laroche et al. 2012).

1. Social networking practices focus on creating, enhancing, and sustaining ties among brand community members.

2. Impression management practices are the “activities that have an external, outward focus on creating favorable impressions of the brand, brand consumers and brand community in the social university beyond the brand community”.

3. Community engagement practices are the processes of working collaboratively with relevant stakeholders who share common goals and interests.

4. Brand use practices are information given by one consumer to another with regards to customizing the product for better applicability to their needs.

Companies that develop strong and efficient marketing strategies to nurture their brand benefit the most when utilizing SMBCs. According to previous research, “earned” advertising passed along or shared among friends demonstrated more significant effects on advertisement recollection, brand awareness, and purchase intent compared to traditional “paid” advertisements. This indicates that traditional marketing strategies may not be as effective when coupled with social media unless platform communities such as SMBCs take up and talk about paid advertising (Khang et al. 2012).

Of note, Swap.com understands the advantages of earned social media, especially the activation of their SMBCs, resulting in innovative marketing strategies. The firm first overcame the consumer-minded stigma of purchasing pre-owned clothing in order to increase and maintain sales. They accomplished this goal by advertising efforts surrounding affordable luxury items, as well as the environmental benefits of clothing sustainability across social platforms. Swap.com regularly promotes the use of their SMBC with campaign hashtags such as #Swaphowyoushop.

For the purposes of this case, metrics were captured from social media posts of Swap.com and five additional SSP accounts from Twitter and Instagram. SSP brand-specific data were also captured from Twitter and Instagram based upon hashtags directly related to these six SSP brands (Table 1). Data capture was limited only by the platform APIs. While the first group of data sets (SSP Brand Accounts) illustrate how the brand talks to consumer communities on social platforms, the latter group of data sets (SSP Hashtags) illustrate how SMBCs talk about SSP brands.

| Table 1 SSP Data Sets | ||

| SSP Brand Account | Instagram Data Set Size | Twitter Data Set Size |

| Poshmark | 891 | 800 |

| Gilt | 1444 | 824 |

| Hautelook | 746 | 800 |

| Thredup | 1208 | n/a |

| Tradesy | 490 | 814 |

| Swap.com | 536 | 668 |

| Accounts Total: | 5315 | 3906 |

| SSP Hashtags | ||

| #gotitongilt | 302 | 65 |

| #giltmanstyle | 783 | n/a |

| #shopmycloset | 171 | 829 |

| #tradesytreasures | 1149 | 16 |

| #hautelook | 693 | 6371 |

| #thredup | 1423 | 7140 |

| #poshmark | 1173 | 1699 |

| #poshmarkcloset | 1586 | 227 |

| #swaphowyoushop | 178 | 47086 |

| Hashtags Total: | 7408 | 63397 |

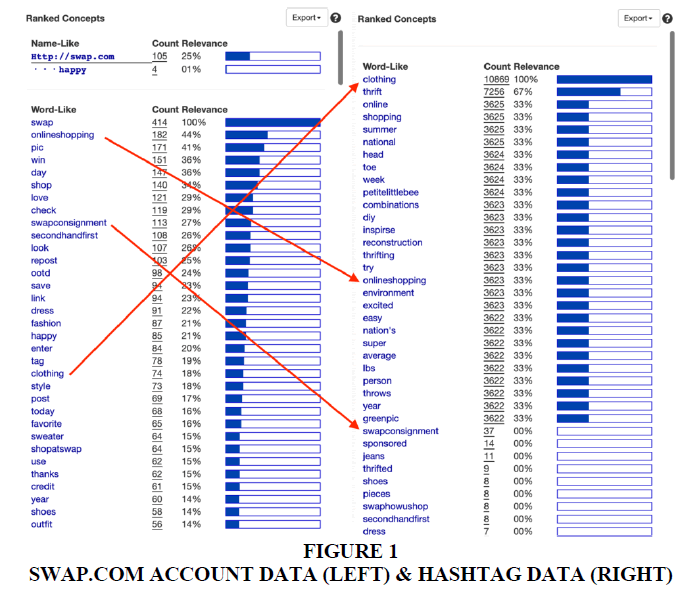

Using industry-grade Leximancer software to analyze the 70,805 SSP social media posts’ textual data, SSP brand managers and analysts can compare brand accounts directly to their SMBCs; these managers may observe how posts differ, or align, when comparing firm-created posts to community-created posts in relation to the thematic content shared there. Figure 1 shows the software’s frequency comparison of the most important themes extant across 7,408 Swap.com posts and 63,397 Swap.com SMBC posts on Twitter and Instagram. It demonstrates that the Swap.com SMBCs expand the range of Swap.com-based brand topics. References to the environment, and unique Swap.com-community hashtag such as “#petitelittlebee can be noted, and several themes do connect (even overperform, such as “clothing”) from firm-created posts to community-created SMBC posts.

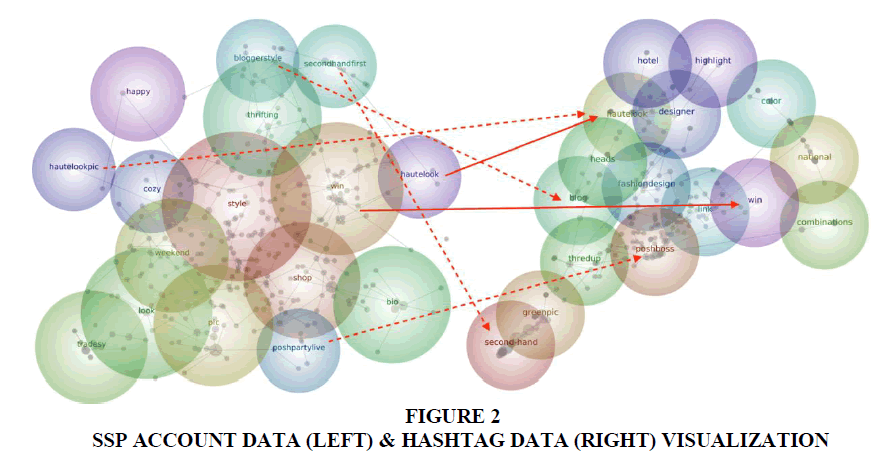

Using the same software to evaluate all six of the SSPs compared to their collective SMBCs across Twitter and Instagram posts, additional trends can be visualized as relevant to all SSPs. Figure 2 shows aggregations of the textual data – the left-hand side features data from SSP accounts, and the right-hand side features data from SSP SMBCs. In some instances (eg., #hautelook), highly frequent post themes are directly related to highly frequent posts of SMBCs. This is particularly true of the specific hashtags SSPs utilize to promote their brand. Other observable instances of SSP account hashtags and terms pollinate SMBC posts (eg., dotted lines); references to bloggers, derivations of SSP-origin hashtags, and connections between style and fashion themes are evident. Additionally, both data sets clearly display frequent reference to winning contests, indicating that SSPs are successful at inducing their SMBCs to discuss social contests conducted on their platforms.

Comparing Swap.com to the other SSPs and their SMBCs, it is clear that Swap.com could do more to create and post about social contests if the firm is interested in aligning itself with other SSP-SMBC co-creation activities. Additionally, Swap.com can continue to accentuate the uniqueness of their brand by emphasizing the conversations on social platforms between their accounts and Swap.com-based SMBCs who talk about being thrifty for the sake of environmentalism or frugality.

There are various benefits for consumers and organizations to participate in brand communities. According to social identity theory, consumers join a brand community to fulfill the need for identification with symbols and groups, which gives participants the ability to augment their self-concept (Dessart, 2017). As luxury apparel brands interact with SMBCs, some users will highlight certain upscale branded products across social posts to bolster their personal and social identities within the community. However, research posits that upscale brands tend to come at higher cost – a limiting consideration as part of SMBCs. Such limitations for upscale SSPs may allow Swap.com to build communities of users that desire to wear specific brands at a more viable cost. Specifically, in reviewing Figure 1, Swap.com could take the lead of a current SMBC and post more about “thrift,” “thrifting,” and the “environment,” or reference “greenpic[s],” given that these non-upscale terms are frequently circulated across social platforms by the organization’s SMBCs.

Obvious benefits of organizations participating in dialogue and value co-creation with communities include SMBCs performing important functions on behalf of the brand, such as providing assistance or socializing to new customers with brand elements, SMBCs educating other customers, brand-communities’ dialogues offering relationship marketing with higher efficiency, and brand-communities’ co-creation activities allowing members to discuss the brand in specific and nuanced ways (Habibi et al. 2014). Swap.com has SMBC-based opportunities that include thriftier and environmentally-focused language, sustained talk about clothing, and consideration of adding additional social contests.

Instructor Notes

Main Topics

1. Swap.com Brand

2. Social Style Platforms (SSP)

3. Social Media Brand Communities (SMBC)

4. Consumer Trends and S-commerce

5. Advertising and Marketing Approaches

Teaching Objectives

1. Understand what a Social Style Platform is

2. How has the rise of social media contributed to S-Commerce

3. Identify what SMBCs are and how they contribute to value co-creation

Discussion Questions

1. What has caused SSP brands like Swap.com to incorporate a children's line/option in their products?

*This answer relates to who the audience is. If Swap.com knows they are targeting mothers, then marketing a children's line may make the brand more successful.

2. What does Swap.com need to do to align with other brands in terms of how they talk about s-commerce? Compare Swap.com’s social account language to that of their community’s themes. Compare Swap.com/Swap-SMBC to all SSPs/all SSPs-SMBCs by reviewing their posts on Instagram, Twitter and/or Facebook. What are the differences and similarities in how SSPs compare to their SMBCs? What opportunities exist for Swap.com as it talks with its SMBCs to sustain those communities and further grow those communities?

*This answer will show how s-commerce and hashtags are used across social platforms to promote SSP social strategy across platforms.

3. What makes Swap.com unique from other SSPs? Why is the brand successful at selling products and expanding brand awareness across social platforms?

*This answer should discuss the different marketing and advertising approaches Swap.com takes by leveraging SMBCs to engage in value co-creation.

References

- Boardman, R., Blazquez, M., Henninger, C. E., & Ryding, D. (2019). Social commerce: Consumer behaviour in online environments. Social Commerce: Consumer Behaviour in Online Environments. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03617-1

- Dessart, L. (2017). Social media engagement: a model of antecedents and relational outcomes. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(5–6), 375–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1302975

- Habibi, M.R., Laroche, M., & Richard, M.O. (2014). The roles of brand community and community engagement in building brand trust on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.016

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23552

- Huang, Z., & Benyoucef, M. (2013). From e-commerce to social commerce: A close look at design features. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 12(4), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2012.12.003

- Khang, H., Ki, E.J., & Ye, L. (2012). Social media research in advertising, communication, marketing, and public relations, 1997-2010. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699012439853

- Kim, J., & Choi, H. (2019). Value co-creation through social media: A case study of a start-up company. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 20(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2019.6262

- Kirsner, S. (2012). After spending more than $11 million, Boston-based Swap.com acquired by Finnish startup for undisclosed amount. Retrieved March 21, 2020, from http://archive.boston.com/business/technology/innoeco/2012/09/after_burning_through_11_milli.html

- Kunst, A. (2018). Do you use the direct-purchase option when you find an interesting product on social media? Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/forecasts/962003/usage-of-direct-purchase-on-social-media-by-us-consumers

- Lam, H.K.S., Yeung, A.C.L., Lo, C.K.Y., & Cheng, T.C.E. (2019). Should firms invest in social commerce? An integrative perspective. Information and Management, 56(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.04.007

- Laroche, M., Habibi, M.R., Richard, M.O., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2012). The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1755–1767.

- Lomas, N. (2012). European Swapping Site Netcycler Confirms Acquisition Of U.S. Rival Swap.com; Launches New Service For Parents To Offload Kids’ Kit. Retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://techcrunch.com/2012/11/02/european-swapping-site-netcycler-confirms-acquisition-of-u-s-rival-swap-com-launches-new-service-for-parents-to-offload-kids-kit/

- Pentina, I., Gammoh, B.S., Zhang, L., & Mallin, M. (2013). Drivers and Outcomes of Brand Relationship Quality in the Context of Online Social Networks. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 17(3), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.2753/jec1086-4415170303

- Perez, S. (2014). Online Consignment Shop For Kids’ Items Swap.com Raises $4 Million Series A. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2014/12/16/online-consignment-shop-for-kids-items-swap-com-raises-4-million-series-a/

- Sorensen, A., Andrews, L., & Drennan, J. (2017). Using social media posts as resources for engaging in value co-creation: The case for social media-based cause brand communities. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 898–922. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-04-2016-0080

- Swap.com. (2016). Swap.com, The Fastest Growing Online Retailer For Pre-Owned Apparel And Household Goods, Secures $20 Million In New Equity Financing. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/swapcom-the-fastest-growing-online-retailer-for-pre-owned-apparel-and-household-goods-secures-20-million-in-new-equity-financing-300375383.html

- Tsimonis, G., & Dimitriadis, S. (2014). Brand strategies in social media. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 32(3), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-04-2013-0056

- Wallace, T. (2019). Omni-channel retail report: Generational consumer shopping behavior comes Into focus + it’s importance in ecommerce. Retrieved from https://www.bigcommerce.com/blog/omni-channel-retail/

- Wertz, J. (2019). Why The Rise Of Social Commerce Is Inevitable. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jiawertz/2019/06/25/inevitable-rise-of-social-commerce/#61dc2b883031

- Wicker, A. (2016). Fast Fashion Is Creating an Environmental Crisis. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/2016/09/09/old-clothes-fashion-waste-crisis-494824.html

- Zadeh, A.H., Zolfagharian, M., & Hofacker, C.F. (2019). Customer–customer value co-creation in social media: conceptualization and antecedents. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27(4), 283–302.

- Zhang, H., Lu, Y., Gupta, S., & Zhao, L. (2014). What motivates customers to participate in social commerce? the impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Information and Management, 51(8), 1017–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.07.005