Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 3

Sustainable Strategies of Ecotourism Enterprises in Conservation Areas: A Case Study of Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha National Park

Shruti Sharma Rana, TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi

Vedika Singh, TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi

Jayesh Panigrahi, Indian Institute of Management Sirmaur, IIM Himachal Pradesh

Arpita Ghosh, Indian Institute of Management Sirmaur, IIM Himachal Pradesh

Citation Information: Sharma Rana, S., Singh, V., Panigrahi, J., & Ghosh, A. (2024). Sustainable strategies of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas: a case study of surwahi social ecoestate kanha national park. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(3), 1-14.

Abstract

Ecotourism enterprises are increasing in number to solve challenges faced by conservation areas. But they are yet to adopt sustainable strategies. The paper conducts a star (STR) mapping for factors for sustainability. The study focuses on operations of Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha (SSEK) in Kanha National Park, India. A materiality matrix was created for SSEK using qualitative semi-structured interviews to generate a SWOP, which was the basis for identifying the challenges and opportunities for the future growth of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas. Sustainable strategies like stakeholder engagement, landscape planning, poverty alleviation, homestays, climate mitigation and resource regeneration were discussed.

Keywords

Ecotourism, Enterprise, Conservation Areas, Protected Areas, National Parks, Materiality Matrix, Sustainability, Sustainable Strategy, Kanha.

Introduction

Conservation areas are extremely fragile. The need for protection of different species of flora and fauna, while ensuring development of peripheral communities can become a clashing point. Tourism in such areas is often viewed with a negative lens. While tourism has brought revenue to such areas, it has been criticised for causing deforestation, shift in riverbeds (Mancini et al., 2022), habitat fragmentation (Areendran et al., 2020), displacement and intrusion of privacy of local tribes, human wildlife conflicts, invasive species and climate change (Ferretti-Gallon et al., 2021); (Rawat et al., 2022).

This has created a discussion among several experts and policy makers, to introduce an alternate form of tourism that is sustainable and ensures conservation of natural resources along with development of local communities. Such a form of tourism must create a synergy between the tourist and the destination. In relation to this, ecotourism has been discussed widely. Overall, ecotourism enterprises are more sustainable and “reliable” for the economy. They contribute to the inclusive development of these areas due to their multiple socio-economic advantages (Arsić et al., 2017); (Yee et al., 2021).

Ecotourism is booming across the globe. In recent years, developing countries are witnessing a high rate of urbanisation. This has increased demand for nature based travel (Sahoo et al., 2022). Post COVID, nature based tourism is seen as an elude for tourists (Hosseini et al., 2021). Apart from their natural seclusion, ecotourism enterprises are much cheaper to operate, and create significantly less disproportion in land ownership from outsiders, unlike large hotels and resorts. They promote and ensure that tourism remains sustainable.

Tourism enterprises are organisations offering different tourism services like tours and accommodation. They are driven mainly by profit. Ecotourism enterprises, on the other hand, are located near natural surroundings. Apart from nature based tourism, they ensure that all their service offerings have minimal ecological footprint. Conservation of the and involvement of all stakeholders, especially development of local communities is their primary goal. On a microscale, when locals or indigenous communities become managers or owners of such ecotourism enterprises, it creates a sense of empowerment among them (Hasana et al., 2022).

Ecotourism enterprises also provide a truly authentic experience, since most of them are homestays. They offer accommodation with locally available food, water, electricity etc. Thus, creating a much lesser carbon foot print. Hotels on the other hand, in their competitive spirit, provide non-local services like spas, swimming pools, air conditioned rooms, restaurants, plastic water bottles etc., to tourists. The transportation of these services, along with installation and maintenance, create a massive carbon footprint in these ecologically sensitive areas. There is also minimum interaction with local communities. The tourist remains unaware of their ecological footprint. Overtime, this makes the tourist equally ignorant. The natural resources in these protected areas also deteriorate with time.

It is necessary to identify strategies that can be used to promote ecotourism in these areas to avoid further loss and damage. The following paper discusses strategies of sustainability through the study of an ecotourism enterprise called Surwahi Social ecostate Kanha (SSEK), located in Kanha National Park, India. The park is a popular attraction, known for its keystone species the Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). The park is an extremely fragile ecosystem with diverse flora and fauna. The beautiful landscape and its central location in India, makes it an extremely popular site for tourism retreats. SSEK, located here, was used to study the relevant strategies for sustainability in ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas for the future.

Problem Statement, Research Purpose and Objectives

Not only does tourism enterprises need to enhance sustainability, but also now ensure regeneration of lost resources to reverse the damage done in the past years. In complex ecosystems like protected areas, local communities often feel disengaged with large scale development. These communities face habitat loss, depletion of resources, poverty and climate change on a frequent basis. Countries with a large tourist population have to ensure that tourism enterprises in and near conservation areas must contribute to development, conservation and adoption of sustainability. There is a dearth of ecotourism enterprises that convert existing knowledge of sustainability into tools for application at the ground level whereby ensuring natural beauty of the place remains intact, even regenerating barren or lost resources.

The purpose of the study is to identify strategies these ecotourism enterprises should adopt to ensure tourism along with sustainable inclusive development, regeneration and conservation of resources in the long run.

The following research objectives have been identified for this research study:

1. To identify the different factors that influence sustainability in ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas.

2. To understand the challenges and opportunities of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas.

3. To discuss trends and strategies for ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas.

Literature Review

The Quebec declaration on ecotourism also laid community building and development the primary goal of ecotourism. It was identified that locations that offer services to tourists only for leisure without any involvement of local communities in its planning or operation is not an ecotourism site (Arsić et al., 2017)(Forje & Tchamba, 2022). The key features of successful ecotourism projects include equity of benefits, transparency of management, environmental efficiency and active participation of locals (Forje & Tchamba, 2022). The analysis of changing trends in domestic tourism in the recent years after the pandemic showed that tourists are looking for site accommodations that offer closeness to the natural green environment. Tourists want a human connection with their destinations (Sahoo et al., 2022).

Ecotourism has been discussed as the foremost component for developing sustainable tourism in conservation areas like national parks. Ecotourism can help in creating awareness of responsible use of natural resources, promote restoration and preservation among park management as well as provide a platform for local community development. Ecotourism is based on development of on-site accommodation, tourism facilities and management of parks along with local community advancement (Sriarkarin & Lee, 2018).

Current Challenges faced by Ecotourism Enterprises in Conservation Areas

Tourism in these areas have become a major means of employment. Excessive commercialisation and overcrowding due to tourism have impacted land, water and other resources. Moreover, the increasing commodification of local cultures, inclusion of non-local commercial activities and high carbon emissions has contributed significantly to the downfall of authenticity in such areas. Conventional tourism models have been criticized as extremely exploitative to host communities. Generally, when tourists visit places for leisure, it is mainly to enjoy its beauty and unique offerings. There is a sense of carelessness in using the resources available in the selected destination. Wastage, emissions and over consumption is common.

Across the globe, conservation areas are plagued by dangers of rising land use for agriculture and construction, transport network, climate change risk and human interference (Farkas & Kovács, 2021a). The effect of “over tourism” is deteriorating resources in these areas (Burbano et al., 2022). Over the years, parks have seen a rise in footfall of tourists. The increase of properties and roads for tourism has hampered not only flora and fauna, but also disturbed water table and soil surface significantly. Other than this, noise, light and water pollution due to tourism activities has been detrimental. Impact of such habitat destruction and pollution has been faced by locals in the form of depletion of water, excessive plastic litter, cycle of floods and droughts, deforestation and frequent man-wildlife conflicts. These areas have become a sphere of “social-conflict” for communities (Farkas & Kovács, 2021a). One of the major challenges in the adoption of eco-tourism, is the piecemeal involvement of the local community. Ensuring that local communities have social and economic benefits is necessary for the thriving of eco-tourism in developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The key features of successful ecotourism projects include equity of benefits, transparency of management, environmental efficiency and active participation of locals (Forje & Tchamba, 2022). The concept of eco-tourism may remain merely a philosophy until it is developed as a tool (Yee et al., 2021). Local communities have acknowledged the potential of ecotourism but hardly have the knowledge to develop it into a considerable business model (Arsić et al., 2017).

Star Scenario Mapping (STR)

Social Mapping

In protected areas, ecotourism impacts society significantly. Collaboration between tourist local communities, government officials, private players, NGOs and global partners is necessary for ensuring sustainability. Each voice is important in decision making. There is a “symbiotic relationship” between tourism and protected areas (Burbano et al., 2022). Studies have revealed different social issues faced by communities in protected areas. Here, many are dependent directly on agriculture which is being threatened with shrinking land holdings, climate change and large scale development of connectivity infrastructure. Many view tourism as a livelihood option. However, there is a dearth in building the social and human capital of these communities. While tourism is only seen as a revenue source, there is a lack of inclusive development in these regions. Development of health, education, local knowledge and handloom culture of these communities are not given primary importance(Kumar et al., 2019). There is also a need to establish a positive relationship between local communities and visitors. Engaging local communities as important stakeholders of tourism businesses will help in social and human development of these regions. Their extreme dependency on national parks often become a rising cause of conflict (Areendran et al., 2020).

While tourism may offer an array of employment opportunities to peripheral communities of such conservation areas, real development occurs when there is equitable distribution of benefits arising from tourism economically as well as socially.

The communities around these conservation areas often have vast traditional knowledge and deep rooted local cultural practices (Areendran et al., 2020). Including them in tourism plans will ensure the sustenance of centuries old arts and culture. International agendas on tourism in and near national parks have all put forward the need for inclusion of poverty alleviation plans. Private and public sectors, both must ensure that tourism businesses include socio-economic development of locals in their strategic plans. Tourism businesses have a larger impact on improving livelihood and human capital in these regions (Pudyatmoko et al., 2018).

Emphasis has been given on two-way “value creation” at a destination. The inclusion of local culture, knowledge, social activities, cuisine, festivities, practices and way of life should be adopted in tourism. Tourism enterprises owned and managed by locals in these regions have the potential to offer an alternate form of tourism that is more sustainable and conscious (Gundersen & Rybråten, 2022).

Technological Mapping

Even though ecotourism enterprises also thrive to be profitable like other tourism businesses, their core value is to offer an experience that is sustainable for all stakeholders (Kernel, 2005). Ecotourism enterprises ensure that they brand their authentic tourism on their media platforms. Such presence and ecolabels are searched by tourists who are aware and consciously choosing better tourism services (Ihnatenko et al., 2020). Technology mapping includes creating a vision and brand image, systematic planning and construction of buildings, climate friendly accommodation facility, setting up waste management systems, monitoring viability of resources around the ecotourism enterprise (Drumm & Moore, 2005).

Technology mapping of ecotourism is necessary; it ensures that development in these areas is consciously done, only after impact assessment on the environment and its stakeholders. Furthermore, technology mapping helps create authentic tourist experiences. As tourists witness and use eco-friendly services, it leads to curiosity, knowledge creation and a feeling of altruism. A vast majority of these tourist seekers feel more satisfied through ecotourism activities (Polus & Bidder, 2016). Many of them witness a shift in their understanding of how these communities survive and live in and around conservation areas.

As tourists become part of the community itself, they learn their culture, lifestyle and economic activity. A sense of belongingness and camaraderie is inculcated in tourists, which enables the creation of responsible behaviour (Polus & Bidder, 2016). Tourists do not see the destination merely as a place of extraction of service offering but a place of contribution. This kind of tourism promotes equality, conservation and responsibility. Some of these experiences develop into habits which tourists carry with them for the rest of their lives.

Resource Mapping

Over the years, parks have seen a rise in footfall of tourists. The increase of properties and roads for tourism has hampered not only flora and fauna, but also disturbed water table and soil surface significantly. Other than this, noise, light and water pollution due to tourism activities has been detrimental. Impact of such habitat destruction and pollution has been faced by locals in the form of depletion of water, excessive plastic litter, cycle of floods and droughts, deforestation and frequent man-wildlife conflicts.

The conservation of natural resources in and around these areas have to be done in line with the sustainable development goals. Eco-tourism ensures visiting and indulging in responsible tourism services in these areas and with nil carbon footprint, emissions and wastage. It has been pointed out there is a need for an advanced approach to management that balances human activity and land development along-with prioritising conservation of natural resources (Burbano et al., 2022) (Schenk et al., 2007).

Regenerative tourism is also being discussed while resource mapping of ecotourism enterprises (Duxbury et al., 2021). There has already been much destruction at destinations. Regenerative tourism talks about regeneration of already lost resources, contributing to betterment of destinations as well as integrating old indigenous methods of conservation into newer conservation practices (Bellato et al., 2022).

Factors that Indicate Sustainability in Ecotourism Enterprises

Derived from star (STR) insights, several specific factors can be mapped for ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas.

North Star Goal Identification

To study the strategies required for sustainability in ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas, a study of Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha (SSEK) was conducted. SSEK is an ecotourism enterprise based in Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India. The idea of this site was conceived by Ankit Rastogi and Pradeep Vijayan in 2015. Covering an area of 10 acres, it is a homestay within an eco-estate. An eco-estate is a large space or property located near a protected area (Alexander et al., 2019). SSEK was formed in 2016, by reusing a semi barren space in the buffer zone of the national park. The land and water resources in the estate were regenerated and revived. The north star goal of SSEK is to practice ecotourism along with conservation and regeneration of natural resources as well as equitable inclusion of local communities.

SSEK was chosen for this study because of several reasons. Firstly, it promotes itself as a truly authentic ecotourism enterprise that has been practicing sustainability in its daily planning, operations and management ever since it was established. Secondly, it is located in Kanha, a park in Central India, accessible for tourists from all its surrounding states. The footfall is extremely high for nature based tourism to Kanha. Thirdly, the park is also facing extreme water depletion, soil loss and displacement of local Gond tribes. In such a scenario, it is relevant to study how with limited resources, SSEK strategizes sustainability along with tourism business in these areas.

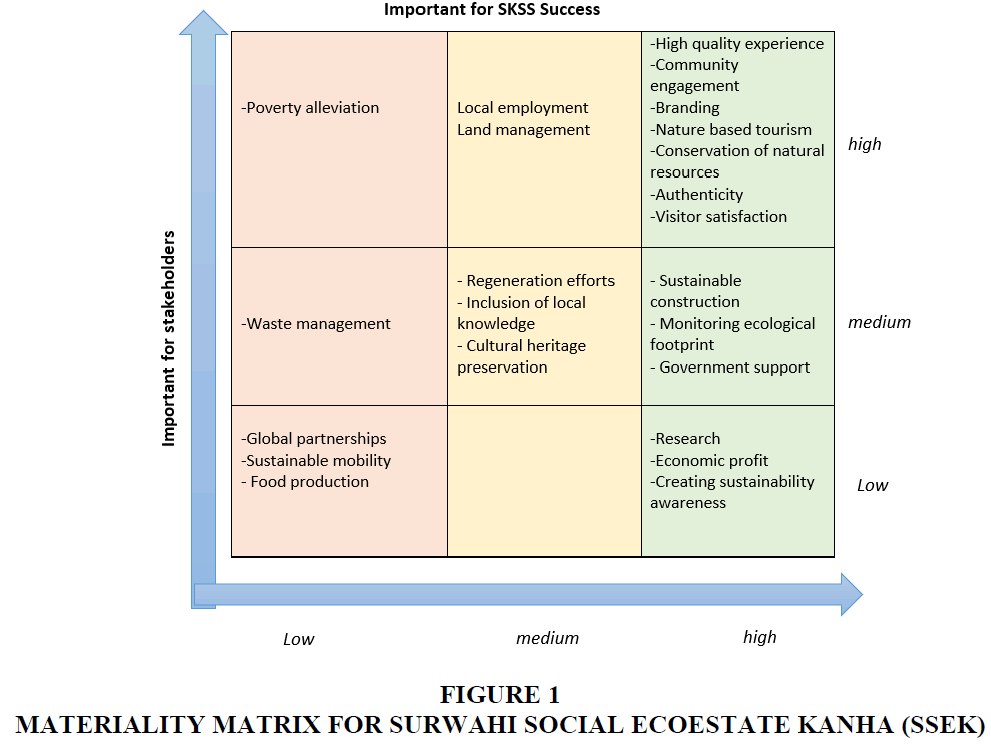

Materiality Matrix

A materiality matrix helps in revealing the important factors essential for stakeholders vis-à-vis business growth. It helps in identifying what matters most to stakeholders and whether it is sustainable for business success or not. The matrix is developed for SSEK. It helps in identifying which all factors are most important for ecotourism enterprise in these conservation areas and which all factors required to be practiced more in the materiality was a concept initially developed in the field of financial accounting. It later began to be used in sustainability strategic planning and reporting. The concept is used to measure stakeholder’s perceptions and its relevance to businesses. A matrix is developed for a particular organisation. It indicates how stakeholders give importance to different factors or material aspects related to sustainability vis-à-vis its impact on the success of business (Calabrese et al., 2019). The materiality matrix has multiple advantages. The matrix helps analyse business performance in the long run. It also helps in identifying what matters most to stakeholders and businesses, so that business strategies can be formed or altered accordingly. The matrix is significant for understanding trends and ESG performance of a company.

SSEK has numerous stakeholders. These include tourists, local rural community at Surwahi, local artisans, private players, experts, forest officials, state government, local assembly (panchayat) et al. During the period of October 2020 to March 2021, data was collected from these stakeholders at Surwahi through a semi-structured interview. The interviewees provided their informed consent for the qualitative data collected. They were asked questions about their perception of SSEK as an ecotourism enterprise. Their answers were used to identify and group the most ‘important factors for stakeholders’. Interviews of owners Ankit Rastogi, Pradeep Vijayan and their manager Narendra Patel were also taken through interaction at SSEK. Their insights were also added from a webinar conducted at Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Sirmaur on 5th December 2020. The webinar was a special talk on 'Pillars of Sustainable and Rural Tourism' where the founders of SSEK were invited to share their experiences on setting up and building an ecotourism enterprise at Kanha. The following table mentions the excerpts from these interviews Figure 1.

From the above information, the following matrix was created for SSEK:

SWOP Analysis

The above materiality matrix is used to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and possibilities for the ecotourism enterprises like SSEK. The SWOP is significant because it helps in creating strategies for ecotourism enterprises for the future. It is essential for understanding the roadblocks and growth potential of ecotourism in fragile ecosystems like conservation areas. Strengths of such enterprises can be enhanced and replicated in other enterprises as it is important for stakeholders and the success of business, whereas weaknesses can be improved for the future.

Opportunities and possibilities help in identifying capacities that need to be augmented. They present impending growth strategies. The following opportunities and possibilities are areas that can be enhanced so as to create better sustainable strategies in ecotourism enterprises for the future Tables 1-4.

| Table 1 Identification of Generic and Specific Factors for Ecotourism Enterprises in Conservation Areas | ||

| Generic factors | Specific factors | References |

| Social | • Global partnerships • Poverty alleviation • Inclusion of local knowledge • Visitor satisfaction • Cultural heritage preservation • Creating sustainability awareness • Local Employment • Government support • Community engagement |

(Ferretti-Gallon et al., 2021); (Pudyatmoko et al., 2018; Yee et al., 2021); (Wang et al., 2021); (Makian & Hanifezadeh, 2021); (Briggs et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2022); (Fuller et al., 2005) |

| Technological | • Brand image • High quality experience • Sustainable construction • Authenticity • Economic Profit • Land management • Sustainable mobility • Research • Waste management |

(Mancini et al., 2022; Yee et al., 2021)(Ristić et al., 2018)(Makian & Hanifezadeh, 2021)(Sørensen & Grindsted, 2021)(Briggs et al., 2022)(Farkas & Kovács, 2021a) |

| Resource | • Nature based tourism • Food production • Low Carbon emissions • Monitoring Ecological footprint • Conservation of Natural Resources • Regenerative efforts |

(Burbano et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2022; Mateer et al., 2020)(Farkas & Kovács, 2021b)(Reindrawati et al., 2022)(Hasana et al., 2022)(Makian & Hanifezadeh, 2021)(Rocca & Zielinski, 2022) |

| Table 2 Interview of Different Stakeholders of Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha (SSEK) | ||||

| Interview for factors important to stakeholders | ||||

| No. | Professions | General Question | Answer | Factors |

| 1 | Caretaker | What is the difference between SSEK and other properties? | Not a hotel but a means for “city people” to connect with rural India. | Local owned and managed |

| 2 | Travel agent | How is it unique for a distribution partner? | Entire resort to yourself with full autonomy and reasonable pricing | high quality experience |

| 3 | Tourist Guest | What is your review on SSEK? | Comfortable and ecological sustainable property; it is a property to be visited again | High quality experience |

| 4 | Journalist | How did you feel at the property? | Wellness and peace of mind | High quality experience, Nature based tourism |

| 5 | Local female caretaker | How was SSEK established? | Initially we were varying of the owners as “outsiders”. Over a period of time as the project developed there is more openness and acceptance. | Community engagement |

| 6 | Local Artist (Raju Banjara) |

Were you receptive to the SSEK project? | The inclusion of local elements in the planning and building of SSEK led to the involvement of all local people in its construction | Local employment, Inclusion of local knowledge |

| 7 | Sustainable certifier | Do you think SSEK meet the certification requirements? | Yes, the property is an amalgamation of preservation of nature in totality, we have hardly seen property that took natural conservation, people and living ecosystem in account. The human race was also included in this concept. | Conservation of natural resources, Preservation of ecosystem diversity |

| 8 | Project researcher (British national) | As leading project developer in Kanha working with elephants, what was your take on SSEK? | Who so ever plans to come to Kanha, must visit SSEK at least one day. | Visitor satisfaction |

| 9 | Spiritual traveller (Canadian Resident in India) | As a person into spiritual travel, what was your view on SSEK. Given that Kanha is crowded with tourists did you feel any solace? | The site is “too good to be true”. The solace and tranquillity found here was enormous. | Authenticity |

| 10. | Foreign tourist (Finnish resident) | What is your feed-back on SSEK? | The slogan Eco is not just used for promotion, but also applied. | Branding |

| 11 | Wild life expert Rajesh Barua | What was the most challenging factor in setting up an ecotourism enterprise? | It was hard to convince the community that this was different from ‘business as usual’. It required a lot of collaboration efforts through local NGOs. | community engagement |

| Interview for factors important to business success: | ||||

| 12 | Owner 1 (Pradeep Vijayan) |

What is the vision of SSEK? | “To preach what we discuss”, the aim is to provide “value for money” with “value for time”. | Economic profit, visitor satisfaction |

| 13 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

What is your take on the government support? | The officials have been very positive in responding to research, safety and conservation of flora and fauna; The Madhya Pradesh (state) government has acknowledged and approved such projects with encouragement. | Conservation of natural resources |

| 14 | Owner 1 (Pradeep Vijayan) |

How did you ensure support from locals? | Engaging with locals was important. We collaborated with local NGOs to help train women, volunteer in schools and local health camps. | community engagement |

| 15 | Owner 1 (Pradeep Vijayan) |

What is your relationship with park officials? | Officials of the park are extremely collaborative. They have promoted sustainable practices and ensured constant communication and promotion of sustainable enterprises. | Government support |

| 16 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

How did you ensure regeneration of ecosystem at SSEK? | Kanha has a major problem of termites and depleting water table. We managed these two by adopting bamboo furniture as well as ensuring regeneration of local forest patches in and around SSEK. A hydrological survey was conducted to recharge old wells. Water harvesting system and Eva transpiration toilets were adopted to save water. | Research |

| 17 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

What is the most authentic aspect of SSEK? | The aim is to provide the best deal not only in terms of money but also in experience. | Visitor satisfaction |

| 18 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

What is your vision for SSEK in the coming years? | We have a vision to adopt more climate change friendly practices and sustainable mobility options. | Nature based tourism |

| 19 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

How should sustainability be included in tourism businesses? | Homestays can help massively in sustainability. Someone’s house has much lower carbon emission than artificially managed resorts that need constant up-keep and beautification. There is less extraction of resources and wastage as it is someone’s home. Eating together, using local resources, etc., also increase awareness of the tourists. | Conservation of natural resources |

| 20 | Owner 2 (Ankit Rastogi) |

What changes have you noticed in an ecotourist especially after COVID? | There is an increasing trend of domestic travel form nearby cities. Millennial tourists are becoming conscious of eco-brands and want to choose places that have lower ecological foot print. “Just like tourism businesses, a tourist also develops over time with more travel experiences.” When tourists stay at an ecotourism enterprise, they look for similar options elsewhere. This creates a demand for sustainable tourism services in other areas too. | Branding, creating awareness |

| Table 3 Strength and Weakness for Ecotourism Enterprises in Conservation Areas | |

| Strengths | Offers high quality experiences and visitor satisfaction to tourists. |

| Engages with local community in and around conservation areas. | |

| Promotes ecotourism as a brand. | |

| Offers authentic nature based tourism. | |

| Ensures conservation of natural resources. | |

| Weakness | Lack of adequate global partnerships. |

| Lack of sustainable options for mobility and transport within and near conservation areas. | |

| Low importance given by stakeholders to ensure local food production and waste management. | |

| Piecemeal efforts for poverty alleviation in these areas. | |

| Table 4 Opportunities and Possibilities for Ecotourism Enterprises in Conservation Areas | |

| Opportunities | Inclusion of local knowledge in building and operation of such enterprises. |

| Steps should be taken to include preservation of local cultural practices of the communities in these areas. | |

| Efforts should be maximised to regenerate lost resources like barren lands, dried up wells, streams etc along with conservation efforts. | |

| Conscious decisions should be made by owners of such enterprises to provide employment to locals especially in managerial positions. | |

| Taking measures for land management of these areas to conserve ecosystem diversity and to evade introduction of invasive species. | |

| Possibilities | Providing more government support through schemes and funds. |

| Possibility for setting up a common measuring tool for measuring ecological footprint of such enterprises. | |

| Promoting creation of sustainable buildings and using local elements in construction projects in ecotourism enterprises. | |

Discussion: Trends and Strategies

The identification of sustainability factors, collection of qualitative data from stakeholders and creation of materiality matrix for Surwahi Social ecostate Kanha along with SWOP analysis was used to identify the trends and strategies for the development of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas for the future.

Domestic Tourism

There has been an increasing trend of domestic tourists. After COVID pandemic, there is a downfall of foreign tourists in conservation areas like Kanha National Park. Most of the tourists are from nearby cities. There is an increase in demand for family based ecotourism activities. Many domestic tourists see conservation areas as a getaway from the urban pollution and fast paced life in metro cities. They are looking for spirituality and peace of mind in these natural areas. As domestic tourism grows, there will be an increasing demand and pressure for nature based tourism. Hence, ecotourism becomes significant in the coming time, so as to ensure that there is less pressure in these areas.

New Consciousness among Ecotourists

Tourists in the recent times have become increasingly brand conscious. Marketing of ecotourism enterprises has become increasingly important. Millennial tourists are specifically searching for sustainable tourism services on booking websites and portals. Many people are choosing only accommodation facilities that have ecolabels. SSEK has ensured that their sustainability is visible on its websites and social media platforms. Registering for ecolabels and responsible awards from global bodies like UNWTO has become increasingly important. A key strategy for ecotourism enterprises has to be in promoting themselves as a sustainable brand.

Integrating Local Elements in Landscape Planning

Setting up ecotourism enterprises involves a comprehensive strategy. Landscape planning and management is extremely important in these areas. Choices like using local available materials in construction building, using recycled wood, terracotta and bamboo, ensuring minimal carbon emissions in transporting activities, setting up water harvesting systems, using natural lighting and GI sheets to save electricity, ensuring replacement of manicured lawns with organic gardens, setting up biowaste toilets and inclusion of local cultural elements and handicrafts for beautification of these enterprises contribute significantly in conservation of local ecology.

Promotion of Regenerative Tourism

Ecotourism enterprises must also adopt regenerative strategies to restore and recover damaged resources. Conducting hydrological and soil surveys will reveal the already existing level of resources in the region. This can be helped to recharge lost resources. Recharging dried up streams, wells and check dams is necessary for conserving water. Planting trees that recharge barren soil and are also not invasive is necessary to ensure protection of diversity. Recreating forest patches on and around ecotourism properties will ensure remarkable changes for the future. The idea is to “leave a place better than before”.

Encouraging Homestays

Homestays contribute significantly to sustainability. A house has much lower carbon emission than artificially managed resorts that need constant up-keep and beautification. Maintaining manicured gardens and other facilities like geysers and air conditioners have a huge ecological footprint. Excessive water use, wood and electricity is common. But at a homestay, these options are limited and often shared. This also helps tourists learn to consciously use resources. There is less extraction of resources and wastage. For instance, the food made in the kitchen is eaten by all guests and water is served in steel glasses. Transporting non-local food and resources to resorts and hotels in such areas also has a huge carbon cost. However, in homestay tourism, such demand is much lower. Such simple practices ensure sustainability. Eating together, using local resources, etc., also increase awareness of the tourists on how local people live and sustain in such areas.

Integrated Stakeholder Engagement

Ecotourism enterprises have to build strategies that ensure inclusion of all stakeholders. Providing local employment in managerial positions, hiring local artists for handicrafts is necessary for empowering such communities. Ecotourism enterprises must compulsorily participate in poverty alleviation programmes through volunteer tourism to create a significant socio-economic impact. Volunteer tourism offers not only societal but also individual development. Studies on the satisfaction level of such volunteer tourists have revealed that they are more likely to feel satisfied from their tourism experience, than their usual tourist experience which does not involve such interaction with local communities.

Climate Change Mitigation

Ecotourism enterprises should include climate change mitigation in all stages of business development. Right from the planning stage, to building and to managing and operating these enterprises, steps to mitigate climate change and lower carbon footprint should be adopted. Alternate forms of energy like solar lamps, panels, water pumps, creation of bio-waste toilets with zero discharge and evapotranspiration mechanisms should be installed. Cooking in a common kitchen area with food locally procured also saves carbon emissions of transporting non local food items. Building open air areas with natural cooling and lighting, conducting energy audits and banning single use plastic are all steps for climate mitigation. Tourists visiting such enterprises also witness the level of importance given to climate change mitigation, this creates awareness and a sense of responsibility among them too.

Conclusion

Conservation areas are nature based tourism. Such forms of tourism dependent on nature can only be sustainable as long as tourism enterprises adopt ecotourism. In recent years, conservation areas have been plagued by several challenges like climate change, habitat loss, displacement of local communities, man wildlife conflict along with depletion of resources. This is further augmented by an overflow of tourists to these sites. Haphazard construction, pollution and overuse of resources in these areas for tourism has led to deforestation. As tourism remerges after the pandemic it is essential to ensure that steps should be taken for the introduction and promotion of ecotourism enterprises on a large scale.

The paper discussed the trend and strategies for sustainability through a Star (STR) mapping of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas. Star mapping helped in identifying social, technological and resource related insights into development of ecotourism. This helped in the identification and enlisting of certain generic and specific factors that indicate sustainability in ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas. These factors were used to identify sustainability in the operations of Surwahi Social Ecoestate Kanha (SSEK) an ecotourism enterprise in Kanha National Park, Madhya Pradesh, India. SSEK promotes itself as a truly authentic ecotourism experience working for the conservation and regeneration of natural resources and community engagement at Kanha. Following the identification of the north star goal for SSEK, a materiality matrix was created through semi structured interviews conducted from its key stakeholders. The matrix revealed the importance of each strategy on stakeholders vis-à-vis overall business success. The next step was to create a SWOP analysis for SSEK, which was the basis for identifying the challenges and opportunities relevant for the growth of ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas in the coming years.

Sustainable strategies adopted by ecotourism enterprises in conservation areas have a ripple effect on the overall socio-economic development of the region. They ensure that the synergy between conservation and tourism remains intact for the future. Ecotourism enterprises also play a significant role in imparting knowledge of sustainability to tourists. These ecotourism enterprises not only conserve and regenerate ecosystems, they also help in empowering local populations. As more and more tourists are exposed to such forms of tourism practices, they behave more responsibly and demand similar experiences in the future. Local and state governments can work with ecotourism enterprises to rehabilitate displaced forest communities through employment. Ecotourism enterprises also help in the development of the local economy and preservation of local cultures through promotion of local handicrafts, cuisine, festivities etc.

The paper identifies that there could be more factors that can be used to measure sustainability in ecotourism enterprises. However, the inclusion of maximum relevant factors has been attempted. The paper can be seen as a starting point for developing more strategies. The scope of this paper is that it can be used by already existing ecotourism enterprises to realign their strategies for safeguarding ecosystem services, to nurture collaboration among different stakeholders and to regenerate lost and damaged resources. Using SWOP analysis, more opportunities and possibilities for development can be adopted for future growth of tourism.

Funding

The authors reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Alexander, J., Ehlers Smith, D. A., Ehlers Smith, Y. C., & Downs, C. T. (2019). Eco-estates: Diversity hotspots or isolated developments? Connectivity of eco-estates in the Indian Ocean Coastal Belt, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Ecological Indicators, 103, 425–433.

Areendran, G., Raj, K., Sharma, A., Bora, P. J., Sarmah, A., Sahana, M., & Ranjan, K. (2020). Documenting the land use pattern in the corridor complexes of Kaziranga National Park using high resolution satellite imagery. Trees, Forests and People, 2, 100039.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arsić, S., Nikolić, D., & Živković, Z. (2017). Hybrid SWOT - ANP - FANP model for prioritization strategies of sustainable development of ecotourism in National Park Djerdap, Serbia. Forest Policy and Economics, 80, 11–26.

Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Nygaard, C. A. (2022). Regenerative tourism: a conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tourism Geographies, 1–21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Briggs, A., Newsome, D., & Dowling, R. (2022). A proposed governance model for the adoption of geoparks in Australia. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 10(1), 160–172.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Burbano, D. v., Valdivieso, J. C., Izurieta, J. C., Meredith, T. C., & Ferri, D. Q. (2022). “Rethink and reset” tourism in the Galapagos Islands: Stakeholders’ views on the sustainability of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2), 100057.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Calabrese, A., Costa, R., Levialdi Ghiron, N., & Menichini, T. (2019). Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 25(5), 1016–1038.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cheng, Y., Hu, F., Wang, J., Wang, G., Innes, J. L., Xie, Y., & Wang, G. (2022). Visitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions in nature-based tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study from Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, China. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 10(1), 143–159.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Drumm, Andy., & Moore, Alan. (2005). Ecotourism development : a manual for conservation planners and managers. Nature Conservancy.

Duxbury, N., Bakas, F. E., de Castro, T. V., & Silva, S. (2021). Creative tourism development models towards sustainable and regenerative tourism. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(1), 1–17.

Farkas, J. Z., & Kovács, A. D. (2021b). Nature conservation versus agriculture in the light of socio-economic changes over the last half-century–Case study from a Hungarian national park. Land Use Policy, 101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ferretti-Gallon, K., Griggs, E., Shrestha, A., & Wang, G. (2021). National parks best practices: Lessons from a century’s worth of national parks management. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 9(3), 335–346.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Forje, G. W., & Tchamba, M. N. (2022). Ecotourism governance and protected areas sustainability in Cameroon: The case of Campo Ma’an National Park. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 4, 100172.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fuller, D., Buultjens, J., & Cummings, E. (2005). Ecotourism and indigenous micro-enterprise formation in northern Australia opportunities and constraints. Tourism Management, 26(6), 891–904.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gundersen, V., & Rybråten, S. (2022). Differing perceptions and tensions among tourists and locals concerning a national park region in Norway. Journal of Rural Studies, 94, 477–487.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hasana, U., Swain, S. K., & George, B. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of ecotourism: A safeguard strategy in protected areas. Regional Sustainability, 3(1), 27–40.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hosseini, S. M., Paydar, M. M., Alizadeh, M., & Triki, C. (2021). Ecotourism supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic: A real case study. Applied Soft Computing, 113.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ihnatenko, M., Antoshkin, V., Lokutova, O., Postol, A., & Romaniuk, I. (2020). Ways to develop brands and PR management of tourism enterprises with a focus on national markets. International Journal of Management, 11(5), 778–787.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kernel, P. (2005). Creating and implementing a model for sustainable development in tourism enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(2), 151–164.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar, H., Pandey, B. W., & Anand, S. (2019). Analyzing the Impacts of forest Ecosystem Services on Livelihood Security and Sustainability: A Case Study of Jim Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 7(2), 45–55.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Makian, S., & Hanifezadeh, F. (2021). Current challenges facing ecotourism development in Iran. Journal of Tourismology, 7(1), 123–140.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mancini, M. S., Barioni, D., Danelutti, C., Barnias, A., Bračanov, V., Capanna Piscè, G., Chappaz, G., Đuković, B., Guarneri, D., Lang, M., Martín, I., Matamoros Reverté, S., Morell, I., Peçulaj, A., Prvan, M., Randone, M., Sampson, J., Santarossa, L., Santini, F., … Galli, A. (2022). Ecological Footprint and tourism: Development and sustainability monitoring of ecotourism packages in Mediterranean Protected Areas. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 38, 100513.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mateer, T. J., Taff, B. D., Miller, Z. D., & Lawhon, B. (2020). Using visitor observations to predict proper waste disposal: A case study from three US national parks. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 1, 16–22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Polus, R. C., & Bidder, C. (2016). Volunteer Tourists’ Motivation and Satisfaction: A Case of Batu Puteh Village Kinabatangan Borneo. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 224, 308–316.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pudyatmoko, S., Budiman, A., & Kristiansen, S. (2018). Towards sustainable coexistence: People and wild mammals in Baluran National Park, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 90, 151–159.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rawat, P. K., Pant, B., Pant, K. K., & Pant, P. (2022). Geospatial analysis of alarmingly increasing human-wildlife conflicts in Jim Corbett National Park’s Ramnagar buffer zone: Ecological and socioeconomic perspectives. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 10(3), 337–350.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reindrawati, D. Y., Rhama, B., Fajar, U., & Hisan, C. (2022). Threats to Sustainable Tourism in National Parks: Case Studies from Indonesia and South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 11(3), 919–937.

Ristić, V., Maksin, M., Nenković-Riznić, M., & Basarić, J. (2018). Land-use evaluation for sustainable construction in a protected area: A case of Sara mountain national park. Journal of Environmental Management, 206, 430–445.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rocca, L. H. D., & Zielinski, S. (2022). Community-based tourism, social capital, and governance of post-conflict rural tourism destinations: the case of Minca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100985.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sahoo, B. K., Nayak, R., & Mahalik, M. K. (2022). Factors affecting domestic tourism spending in India. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schenk, A., Hunziker, M., & Kienast, F. (2007). Factors influencing the acceptance of nature conservation measures-A qualitative study in Switzerland. Journal of Environmental Management, 83(1), 66–79.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sørensen, F., & Grindsted, T. S. (2021). Sustainability approaches and nature tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 91.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sriarkarin, S., & Lee, C. H. (2018). Integrating multiple attributes for sustainable development in a national park. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 113–125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, W., Feng, L., Zheng, T., & Liu, Y. (2021). The sustainability of ecotourism stakeholders in ecologically fragile areas: Implications for cleaner production. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yee, J. Y., Loc, H. H., Poh, Y. le, Vo-Thanh, T., & Park, E. (2021). Socio-geographical evaluation of ecosystem services in an ecotourism destination: PGIS application in Tram Chim National Park, Vietnam. Journal of Environmental Management, 291.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 31-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14134; Editor assigned: 01-Nov-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-14134(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Dec-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-14134; Revised: 29-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14134(R); Published: 06-Mar-2024