Research Article: 2025 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Strategically managing pro-social endeavors of the enterprise to the benefit of both the firm and the well-being of the greater environment in which it operates

B. Keith Murray, Bryant University

Citation Information: Murray, K., B. (2025). Strategically managing pro-social endeavors of the enterprise to the benefit of both the firm and the well-being of the greater environment in which it operates. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 24(1), 1-14.

Abstract

This article proposes that the singular, distinctive purpose of the business discipline of marketing can and should be used to encourage, foster, and then strategically manage all pro-social endeavors of the organization to the mutual benefit of society and the enterprise, all in a way that parallels other, more conventional “products” of the firm. This approach is predicated on conceiving of the pro-social actions of the firm as “product offerings” to be managed as elements of mutual “value” to both the enterprise and, at the same time, various stakeholders and, hence, strategically managed. The case is made that strategically overseeing the prosocial activities of the enterprise promotes the well-being of the firm’s (external and internal) stakeholders and at the same time benefits the organization. Distinctive marketing paradigms to be employed include research and analysis in terms of various stakeholder groups, the new product development process, and portfolio management.

Keywords

Product Strategy, Strategic Management of Sustainability, Strategic Management of Stakeholders, Pro-Social Strategic Management.

Introduction

A long history in academic literature exists that foreshadows current interest in and demand for greater business enterprise to manifest more substantial responsiveness to the wider social milieu and environmental sustainability. Indeed, a great amount of scholarly attention has been devoted to the worthy concepts of ethical business behavior and, ideally, the adoption of a pro-social focus by commercial entities. This literature stream spans five decades and crosses all functional areas of business.

Nonetheless, while the important implications of pro-social actions on the part of the firm have historically been noted at length (e.g., Cottrill, 1990) a widely applicative model that relates to existing (and potential) pro-social management frameworks and which is integrated into the strategic considerations of the firm has been lacking, despite strong sentiment among advocates that pro-social endeavors are potentially key strategic elements of the firm (e.g., Borland et al., 2016; Gabaldon & Gröschl, 2015). To make matters worse, an absence of meaningful and actionable paradigms in this area fosters the belief among business critics that pro-social undertakings are, from the enterprise’s perspective, superfluous and, thus, portraying the modern commercial entity to being cast simply as an economically self-serving, greedy, and opportunistic.

Thus, key marketing relevant issues addressed here seek to underscore three central notions: (A) that corporate social endeavors undertaken by the firm can be seen as “products” whereby social action(s) on the part of the firm and represent important exchanges of value between the enterprise and various constituent stakeholders; (B) that the management of such exchanges are conceptually—and practically—a logical extension of what the enterprise does already with respect to more typical and conventional product offerings; and (C) that if understood and managed strategically, pro-social endeavors pose favorable opportunities for success and benefit, both to the firm and society at large.

This article describes the conceptual and the managerial component elements for firm management to approach pro-social activities to, in part, gain strategic and market advantage. It is organized in four sections; (1) a product management paradigm is proposed by which corporate social policy can be guided in a strategically relevant manner by an extant management framework; (2) a development process for corporate pro-social activities and “products” is described; (3) the on-going management of the pro-social product using extant marketing frameworks; and (4) the implications and relevance of such a product development andmanagementorientationarediscussed.

The case for managing pro-social exchanges using marketing paradigms

The call for pro-social action on the part of commerce is, indeed, long-standing; principal themes of early pro-social thought underscore the importance, obligations, and various aspects of pro-social behavior on part of the business (e.g., Bowen, 1953; Walton, 1967). Subsequently, several over-arching management models were proposed that pointed to the adoption and management of pro-social corporate endeavors; for example, Robin and Reidenbach (1987), using social contract theory and the reformulation of corporate culture as a means for incorporating social responsibility into the strategic marketing plan process. Subsequently, Murray and Montanari’s (1986) product orientation relative to the corporate social responsibilities (CSR) process assigns pro-social decision making to an organizational “home” (i.e., specifically as a part of the marketing function) and specifies the context in which it could be “managed.” However, both models fall short of delineating an institutional process, per se, by which pro-social actions on the part of the firm might occur.

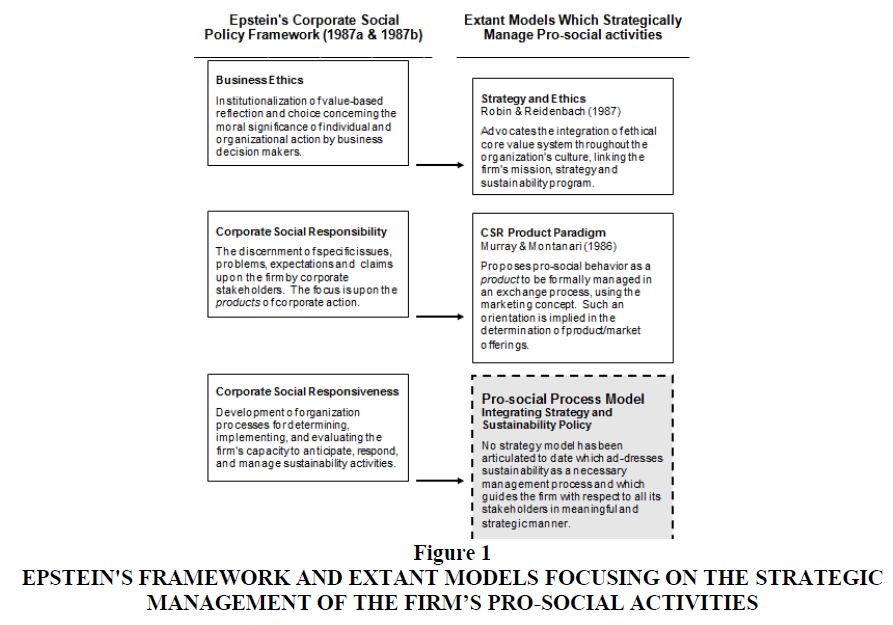

Finally, Epstein (1987a, 1987b) brings pro-social and business ethics together into what he termed corporate social policy processes. Fundamentally, the corporate social policy process is the institutionalization within business organizations of the following three elements... “Business ethics, corporate social responsibility and corporate social responsiveness” (p. 106). These three management Perspectives, in effect, serve to frame the adoption and cultivation of pro-social programs within existing, established management systems (figure 1).

Figure 1 Epstein's Framework and Extant Models Focusing on the Strategic Management of the Firm’s Pro-Social Activities

What immediately follows is the development of such a model, premised on the notion of an exchange process that conceptualizes pro-social behaviors as product offerings of the firm in a way that is mutually promising in terms of the firm and the greater social and natural realities and points to the opportunity to be strategically managed.

Conceptualizing pro-social programs as “products” to be valued and managed

That all manner of commercial, financial, and social exchanges occur between the firm and its relevant environment is readily apparent; indeed, key transactional relationships of importance to the firm and its various stakeholders exist which are called upon to be specifically managed for optimal value; multiple management functions of any firm formally oversee processes involving exchanges of value and benefit, both to the firm and its transactional partners (e.g., Kotler, 1972; Pride & Ferrell, 2000). Hence, a product conceptualization of sustainability and pro-social offerings is not without basis as a useful perspective since corporate pro-social actions, by definition, advances the well-being of society as well as the means by which satisfaction is achieved by both the organization and one more of its stakeholder groups (Evans et al., 2017).

Since its formal inception, the marketing discipline has been predicated on managing product offerings (i.e., goods and services) whereby a voluntary exchange occurs between two or more parties in transactions involving elements of mutual value. More recently, contributions in the field of sustainability have recognized the concept of “value” as a worthy perspective to view such transactions (Boons et al., 2013). While the dominant emphasis in social responsibility literature has focused on the obligations of the corporation to advance society, virtually no attention has been focused on benefit to the firm stemming from elementsofvaluefromtheStrategicexchangefrompro-socialbehavior.

Addressing a more complete array of stakeholders in the corporate pro-social process

In a free-enterprise system, the typical, implicit purpose of any commercial entity is to generate benefit from transactions involving “buyers” and/or users of the firm’s conventional offerings. However, other indirect parties (i.e., stakeholders) are feasible, including investors, affected communities, and regulators. Indeed, a stakeholder orientation with respect to pro-social endeavors of the firm has been long been acknowledged by wide range of scholars (e.g., Ferrell & Ferrell, 2022; Laczniak & Shultz, 2021; Paulraj et al., 2017).

Thus, the notion of corporate pro-social activity as a product offering, points to it having strategic significance since pro-social offerings represent real costs to the firm, but which—in the same transaction—pose real value to both the firm and stakeholders (see Fischer et al., 2020). This implies that an opportunity exists for the firm to manage its corporate social offering in a manner not unlike that of a product, per se, one that potentially benefitsbothsocietyandtheorganization.

Types of corporate social products and corporate benefit

Pro-social activity, by definition, attempts to make a positive contribution to the greater environment of the firm; Such effects were articulated decades ago, also in terms of advancing the various dimensions of economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic considerations of the firm (Carroll, 1991b); those early themes are still amply evident in management literature (e.g., Drori et al., 2020; Martínez‐Ferrero & Frías‐Aceituno, 2015).

However, in contrast to an abstract, noncontingent conceptualization of how pro-social endeavors effect the firm, the dichotomy between direct and indirect benefit is instructive since such a framework enables the firm to better anticipate and achieve instrumental outcomes from engaging in certain exchange processes. Examples in this regard include favorable employee attitudes and performance (e.g., Farooq et al., 2014; Story & Neves, 2015) as well as positive effects on enterprise valuation (e.g., Vallentin & Murillo, 2012; Vilanova et al., 2009).

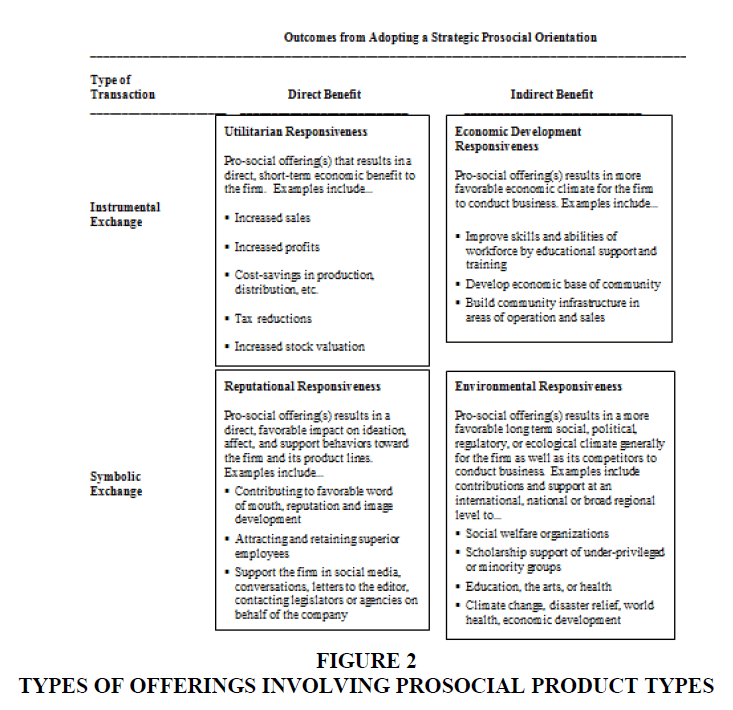

Thus, indirect benefit from pro-social actions rendered by the firm can be viewed as cultivating a more favorable climate in which the firm operates, competes, and is regulated; positive effects of an indirect nature can be seen as being composed of predominantly favorable regulatory and noneconomic conditions stemming from its pro-social actions (e.g., Glavas & Kelley, 2014; Mory et al., 2016; Story & Neves, 2015). To effectively plan and manage the strategic outcomes to the enterprise, a way of organizing and managing exchange events involving pro-social offerings is called for. Absent such a management framework, it would be difficult to both plan the strategic role with respect to any pro-social offering as well as assess the various effects such behavior might have with respect to the firm. Thus, to gauge benefit effects to the firm, a systematic arrangement of feasible corporate social products needs to be erected, based on type of transaction and benefit anticipated. These types include pro-social offerings that address utilitarian responsiveness, economic development responsiveness, reputational responsiveness, and environmental responsiveness. Each of these will be described briefly.

Utilitarian responsiveness

Pro-social activities involving instrumental exchange with key publics and which lead to a direct, short-term economic benefit to the firm represent utilitarian responsiveness. These pro-social products constitute offering(s) which result largely in enhanced sales, elevated profit, and/or cost savings in the form of economies of scale, more efficient use of resources, tax benefits, etc. Utilitarian responsiveness produces a direct benefit to the firm and which occurs when economic exchanges involving the sale of conventional offerings or the operations of the firm are positively affected.

Economic development responsiveness

Not all pro-social products offer the firm immediate, direct economic advantage. Pro-social products that represents economic development responsiveness lead to improvement of the general environment in which the firm operates. A firm may advance its competitive well-being by enhancing the conditions that surround it; this frequently involves improving the skills and abilities of the workforce it draws from, contributing to the economic well-being and buying power of the corporate milieu, enhancing the social infrastructure of the communities that surround its operation and thus enhance the attractiveness of the marketplace generally in which the firm exists and potentially could benefit from.

Reputational responsiveness

Not all transactions between a firm and the marketplace are necessarily economic in nature. Reputational responsiveness effects constitute pro-social offerings that result in a direct, favorable impact on the ideation, affective, and/or behavioral aspects of stakeholders; such exchanges are fundamentally psychological in nature and in a technical sense precede transactions of a tangible or monetary nature; they are attitudinal in nature and can be described in terms that denote the belief or affect structure of relevant groups in the short-term but which may in the long-run potentially lead to other favorable actions or behavioral intentions toward the enterprise.

Types of affective and behavioral response by stakeholders include recommending the firm to others for its investment or employment potential; defending or supporting the actions of the firm in conversation or favorable correspondence to those who influence public policy.

Environmental responsiveness

Pro-social actions of the firm characterized by noneconomic transactions and which pose, at best, only indirect benefit to the firm are classified as environmental responsiveness effects. In general, these offerings result in a more favorable social, political, regulatory, and ecological climate for the firm to operate in. Like reputational responsiveness, utility to the firm of responsiveness behavior is, in the short-term at least, marked by fundamentally nonfinancial rewards from constituent groups; while the company may benefit in the long-run from fostering a more favorable social-regulatory-ecological climate, other social and economic entities potentially benefit as well.

A key consideration of environmentally pro-social corporate actions addresses the notion that this type of responsiveness on the part of the firm represents largely disinterested support of worthy causes and transpires without the necessary expectation of either direct nor immediate economic gain; examples of such pro-social endeavors include advancement of minority employees; support of the fine arts; scholarship endowment programs for worthy students or underprivileged children; or, in the case of a utility company, subsidies for needy or senior citizens.

Figure 2 shows the relationships among the four social responsiveness product types with respect to exchange type and degree of direct benefit to the firm.

Although the discussion to this point has sought to describe a typology of pro-social offerings with respect to product types, two additional points are called for. First, a “product” typology that seeks to erect a means whereby pro-social behavior by the firm can be exclusively classified in terms of one of four product types may not be possible. In reality, the simple assignment of pro-social behavior to one quadrant (in Figure 2) to the exclusion of any one or more of the other three may in some cases be difficult to defend. Instead, conceptualizing the primary product type might be best accomplished by determining the most direct and immediately tangible exchange possible to a firm from the offering of a given pro-social product. A second point to be made is the observation that typology provides not just a means of classifying any one pro-social offering, but also points to a basis for erecting a pro-social product portfolio for a given corporate entity.

In any case, a market perspective is called for, predicated on a stakeholder analysis of the firm’s relevant publics (e.g., Epstein, 1987a, 1987b; Ullmann, 1985) and which implies a market segmentation approach to pro-social activities. Zeithaml and Zeithaml (1984) suggest that corporate social activities create and extend opportunity for the organization to influence the environment and urge that the firm adopt a pro-active strategy with respect to its environment.

Pro-social environmental assessment process

The identification of social product-markets can be viewed as a two-step process. Given the desire of the firm to strategically focus the pro-social endeavors of the firm, the first step in defining social product-markets calls for the identification of key stakeholders of interest to the organization. This task presumes a thorough knowledge of the socio-political environment of the firm and, ideally, an appreciation of the strategic role and relative importance of various groups, both internal and external to the firm.

The identification of social responsibility product-markets suggests that subsequent to the process of segmenting the socio-political environment of the firm into distinct constituent publics, segments can be matched with particular interests, needs, and/or problems (e.g., Day, Shocker, and Srivastava 1979). Thus, a second phase of the product/market analysis is necessary, one that seeks to identify relevant issues for each population identified as a potentialsocialmarketofinteresttotheorganization.

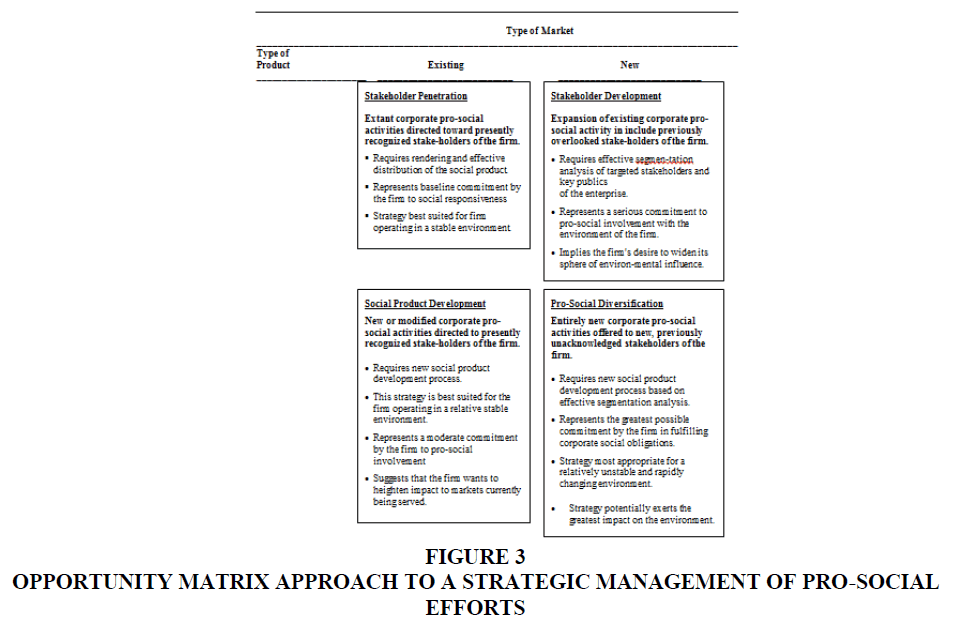

Social product planning using a product/market opportunity matrix

In terms of planning and managing the social responsibility product line, a useful framework to employ in allocating corporate resources is in the application of a product/market opportunity matrix (Ansoff, 1957). In the context of this framework, existing and potential pro-social markets can be evaluated in terms of identifying four competing strategies which facilitate positive interest group exchanges: Stakeholder penetration, stakeholder development, social product development, and pro-social diversification. Each of these alternative product/market strategies is noted and briefly discussed.

Stakeholder penetration

Insofar as corporate pro-social products are concerned, a stakeholder penetration strategy represents a minimal yet fundamental commitment to pro-social behavior by the organization. Firms which employ this social product strategy seek to continue current pro-social behaviors with respect to existing pro-social offerings and confining the extent of such activities to presently acknowledged key publics. The product planning strategy for the firm with this perspective includes the evaluation of existing corporate social behaviors in terms of achieving full potential among existing societal stakeholders of the firm.

Stakeholder development

This strategic alternative focuses a firm’s desire to widen its environmental influence by reaching new constituent groups without expanding its social product “line.” This strategy implies the expansion of existing corporate responsibility behaviors to affect previously unaddressed stakeholders, or expanding the dissemination of information to new, strategically important publics regarding extant corporate responsiveness of the firm in its social, political, or ecological sphere. Ultimately, the pursuit of a market development strategy implies a firm’s greater commitment to engage in socially responsive behaviors and a more sophisticated approach to carrying out that intention.

Social product development

For socially relevant exchanges to occur in a shifting environment, a product planning approach proposes that the firm offer new or modified corporate behaviors to existing constituent groups. A social product development strategy implies that the organization should further its social commitment to existing stakeholders by engaging in corporate activities that build on or complement pre-existing pro-social offerings. Product line extensions suggest a growing commitment of the firm to fulfill a corporate obligation in an evolving social environment.

Pro-social diversification

This strategy suggests the development of new social products targeted to new constituent groups. While new product development is, to varying degrees, essential for all organizations, a social product diversification strategy would appear to be especially appropriate for firms in industries that are potentially subject to rapidly changing environmental conditions, including regulatory oversight, adverse investor sanctions, or adverse mass-media attention. Social product diversification represents a relatively high level of commitment on the part of the firm to addressing social issues. Furthermore, a diversification strategy points to the greatest interest by the firm to be socially responsive.

Figure 3 shows an opportunity matrix approach to the management of pro-social products and identifies key strategic implications of its application.

In the absence of a management process to guide innovations, a firm is subject, at best, to costly trial-and-error efforts at introducing social products. At worst, a firm without such a process to guide diversification efforts runs a risk of failing to enact relevant social behaviors in a timely fashion, if at all. In the discussion that follows, an application for the development of social responsibility products is presented which outlines an approach to innovation for pro-social corporate offerings.

A systematic process to identify and manage pro-social activities of the firm

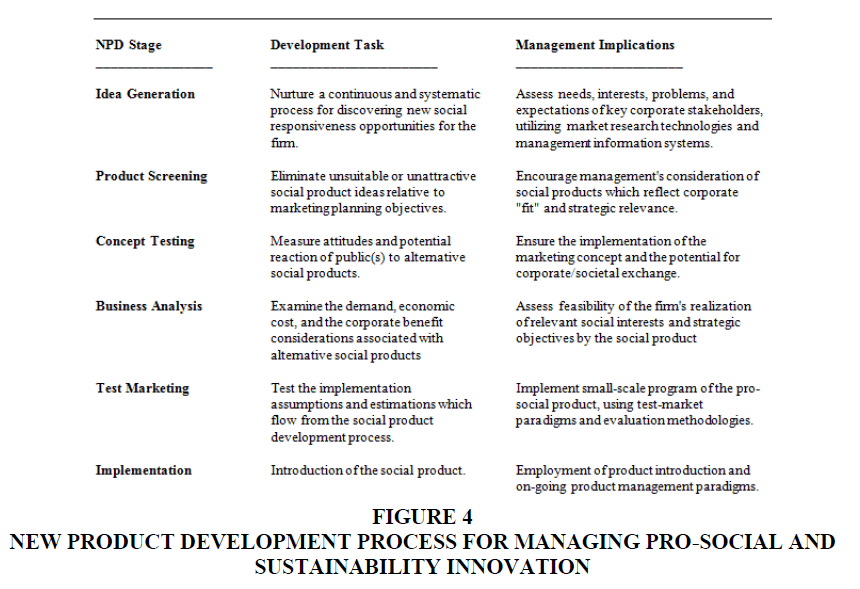

The need for a systematic and specific social product development process is evident, given the increasing demand for sustainability and pro-social programs by various constituencies of the modern firm, all in addition to a continuing vulnerability to regulatory and legal sanctions. Consistent with long acknowledged models (e.g., Hisrich & Peters, 1984), it is proposed that a promising and worthy planning process for new social responsibility products involves a series of systematic steps consistent with more conventional, tangible offerings of the firm as noted below.

Idea generation

In a continuous and systematic process to discover new social responsiveness opportunities, the pro-social firm must develop an organizational structure that fosters the generation of new pro-social product concepts. Idea sources for social products include attending to such groups as employees, customers, investors, competitors, academicians, public officials, governmental agencies, clergy, consumer action groups, institutional “think tanks,” and ethicists. In addition to extant management and marketing information systems, the search for social product opportunities among these and other groups would logically utilize market research methodologies and information gathering approaches presently available to enterprise marketing professionals.

Management alternatives for organizational structure that encourage idea generation of social responsibility products include designating a social responsibility product manager, a product planning committee composed of a cross-section of corporate decision-makers, a new-product planning department, and/or corporate responsibility venture teams. Regardless of the organizational scheme selected, that the pro-social firm institutionalizes a search process for social product opportunities is imperative.

Product screening

After potential social responsibility product ideas have been identified, the firm is confronted with the need to screen unsuitable or otherwise unacceptable or unattractive ones. The purpose of social product screening is to provide a consistent and systematic way, with limited management emotion and bias, to evaluate new product opportunities against one another as well as in terms of the firm’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats, and resources. Thus, with respect to product screening, criteria should be developed against which corporate decision-makers can weigh the merits of social product ideas, including “fit” with corporate mission (e.g., Robin & Reidenbach, 1987), strategy, goals, expected technologies and resources, the number and size of publics affected, appeal to legislative/regulatory agencies or consumer/political action organizations; and the potential for generating positive, pro-firm attitudes and behaviors by key publics.

Concept testing

To promote the development of market-relevant social products, information directly from the socio-political environment of the firm is ideal. Concept testing implies data collection from key sectors internal and/or external to the firm to measure attitudes and potential reaction to feasible alternative social products potentially offered by the firm. Social product concept testing is predicated on the measurement of the relative merit of social product opportunities by samples drawn from important stakeholder segments. This step in the product development process represents the opportunity to receive input from various external realities of the firm. In short, while product screening serves in some ways to restrict social innovation by the firm, concept evaluation, by contrast, promotes the development of social products which are relevant and most desired by stakeholders. Given the role of social products in the strategic orientation of the firm, the objective of concept testing is to be responsive to public demands in a proactive rather than a reactive sense. In the long run, pro-social planning and concept testing represents greater benefit to both the firm and society by fostering a focus on pro-social offerings of mutual value to the enterprise and its stakeholders.

Business analysis

This aspect of the new product development process more rigorously examines the demand and economic cost considerations, as well as the social and corporate benefit factors, associated with the feasible social product. The notion of viewing pro-social programs in terms of economic benefit of the firm is not new; CSR scholars have long examined profitability considerations of the socially progressive organization (e.g., Aupperle et al., 1985; McGuire et al., 1988; Starik & Carroll, 1990). Indeed, some have vigorously argued that social product activities need not be liabilities to the firm, but instead can be profitable for the firm (Norris, 1985). In any case, only systematic business analysis can determine the economic implications associated with a pro-social product concept and its effective “cost” to the firm.

Test marketing

Test marketing the social responsiveness product involves implementing the corporate behavior on a selected, controlled basis to observe the anticipated versus actual outcomes and costs under real-world conditions. As with more conventional product innovations, the test market for some corporate social responsiveness products may be omitted, depending on the specific considerations surrounding a particular decision.

If corporate decision-makers are thoroughly committed to a social action, despite specific cost considerations, then a market test may be viewed as superfluous. Also, as advances in technology occur, socially responsive measures may simply be imperative for the corporation to implement, without which avoidable and potentially harmful effects are averted (e.g., when a firm reduces its environmental pollution as new manufacturing methods become available).

Implementation and on-going product management

As the final stage in the social product development process, introduction of a particular pro-social product offering to the world represents both the end of the product development process and the beginning of the product management process. Murray and Montanari (1986), suggest that the marketing function of the firm could be instrumental in evaluating and managing corporate performance in rendering social responsibility offerings. A distinctive contribution to the external social product management process by the marketing function would include the ability to perform cost assessment and control, periodic market audits.

The model proposed here manifests a numbers of advantages, including conceptualizing pro-social activities of the firms as a worthy and manageable strategic undertaking. An additional-but-subtle element is the delineation of an on-going, systematic management process for pro-social success. Figure 4 offers an overview of this process.

Key implications of strategically managing pro-social “products”

This article proposes that the greater marketplace should guide strategic and corporate decision-makers in the development of socially responsive behaviors of the organization, since the firm and its environment are interdependent social entities engaged in other, obvious exchange relationships. In the discussion that follows, evaluative aspects of the contribution are critically presented which first pose an expected objection and, subsequently, offer feasible arguments in favor of the premises and implications of the model.

An enterprise ought not “profit” from engaging in pro-social activities.

The issue raised by critics here argues that if a firm benefits from a socially responsible act it is indicative that a “good business decision” was made, rather than fulfillment of a true responsibility to society. This raises the obvious question as to why the firm should get “credit” for pro-social endeavors when it is likely doing something that is, in fact, serving its own interests as well; in other words, critics might pose the question, shouldn’t the enterprise “take a hit” to be seen as making a contribution to society?

A response to such detractors argues that to the degree it can be demonstrated to business decision makers that pro-social engagement represents an intersection of strategic benefit to the firm and gain to the greater society, the more probable pro-social activities are likely to be conceptually acknowledged, undertaken, and continued by commercial enterprises.

The favorable aspects of an articulated pro-social management model

Although promising in concept, the formal, strategic, and systematic management of wide-ranging pro-social programs, certainly in term of the recognition, acceptance, and practice of such, is largely absent in the world of commerce (e.g., Nosratabadi et al. 2019; Geissdoerfer, Vladimirova, and Evans 2018). Business models to date have been lacking or proven disappointing in the systematic management of pro-social and sustainability efforts in the business sector (e.g., Upward & Jones, 2016). Thus, to encourage a more wide-spread adoption of pro-social efforts on the part of the enterprise sector, it makes management sense to foster worthy and proven oversight and management models (Lahti et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2017). From the perspectives proposed here, the adoption of a formal, strategic pro-social management model framework leads to several favorable implications that will be considered in the final section that follows.

A product perspective elevates pro-social actions to a fundamental business interest and strategic activity

An obvious implication of a pro-social product model is the ease with which pro-social behavior can be shown to be a “natural” business function. How the process of guiding a firm’s social responsibility undertakings can be specified and guided by extant frameworks for product development and management would work to foster a wider acceptance among corporate managers. Indeed, extant, recognized marketing paradigms strategically link prosocial content and process issues together. What has heretofore been considered essentially the special interests of pro-social and sustainability advocates now becomes feasible to integrate into enterprise-familiar paradigms which specify the “who,” the “what,” the “when,” and the “how” of pro-social management in a strategic and meaningful way already and inherently recognized by enterprise execs.

A pro-social product approach enhances the firm’s ability to better achieve other strategic goals and objectives

The importance of developing an ethical corporate framework notwithstanding, the model proposed here suggests that what constitutes the content of pro-social offerings is shaped significantly by the strengths and weaknesses that characterize the firm as well as the threats and opportunities that are external to it. With the influence of these factors being brought to bear in the determination of social products offered by the firm, the enterprise is enabled to more strategically justifies and integrates social programs into a plan that maximizes value to the firm as well as more fully supports the mission of the firm in society.

Process management using marketing paradigms promotes on-going, responsive decision-making

Acceptance of a pro-social management process suggests that corporate responsibility behaviors are not the result of a once-for-all decision process. Instead, a prosocial product approach implies that corporate responsiveness is an on-going series of decisions, undertakings, and, in turn, outcome events, all of which require the continued attention of decision-makers. Indeed, pro-social activities represent investments in the future well-being of the enterprise and the societal context in which it operates. As such, management of the social product(s) of the firm requires on-going planning, analysis, and strategic action.

Conclusion

Clearly, while it is not feasible for the business sector--much less any single firm--to fully address all manifest societal needs. the model offered here offers two readily attractive features: (1) It is framed in universally recognized and well-understood management terms and (2) if adopted, the pro-social marketing management paradigm articulated here points the way for an enterprise to purposely respond to the ever-changing pro-social demands of the firm’s environment, all the while simultaneously advancing the interests of society and the enterprise in a meaningful way for both entities.

References

Ansoff, H. I. (1957). Strategies for Diversification. Harvard Business Review, 35, 113-124.

Boons, F., Montalvo, C., Quist, J., & Wagner, M. (2013). Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: an overview. Journal of Cleaner Production, 45, 1-8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Borland, H., Ambrosini, V., Lindgreen, A., & Vanhamme, J. (2016). Building theory at the intersection of ecological sustainability and strategic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(2), 293-307.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. Harper & Row.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39-48.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cottrill, M. T. (1990). Corporate social responsibility and the marketplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(9), 723-729.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Day, G. S., Shocker, A. D., & Srivastava, R. K. (1979). Customer-oriented approaches to identifying product-markets. Journal of Marketing, 43(4), 8-19.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Drori, I., Manos, R., Santacreu-Vasut, E., & Shoham, A. (2020). How does the global microfinance industry determine its targeting strategy across cultures with differing gender values? Journal of World Business, 55(5), 100985.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Epstein, E. M. (1987a). The corporate social policy process and the process of corporate governance. American Business Law Journal, 25(4), 361-383.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Epstein, E. M. (1987b). The corporate social policy process: beyond business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and corporate social responsiveness. California Management Review, 29(3), 99-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Evans, S., Vladimirova, D., Holgado, M., Van Fossen, K., Yang, M., Silva, E. A., & Barlow, C. Y. (2017). Business model innovation for sustainability: Towards a unified perspective for creation of sustainable business models. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(5), 597-608.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 563-580.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fischer, D., Malte, B., & Mauer, R. (2020). The three dimensions of sustainability: A delicate balancing act for entrepreneurs made more complex by stakeholder expectations. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(1), 87-106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kotler, P. (1972). A generic concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 36(2), 46-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Laczniak, G., & Shultz, C. (2021). Toward a doctrine of socially responsible marketing (SRM): A macro and normative-ethical perspective. Journal of Macromarketing, 41(2), 201-231.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nosratabadi, S., Mosavi, A., Shamshirband, S., Zavadskas, E. K., Rakotonirainy, A., & Chau, K. W. (2019). Sustainable business models: A review. Sustainability, 11(6), 1663.

Upward, A., & Jones, P. (2016). An ontology for strongly sustainable business models: Defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organization & Environment, 29(1), 97-123.

Vallentin, S., & Murillo, D. (2012). Governmentality and the politics of CSR. Organization, 19(6), 825-843.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vilanova, M., Lozano, J. M., & Arenas, D. (2009). Exploring the nature of the relationship between CSR and competitiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 57-69.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 02-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. ASMJ-24-15413; Editor assigned: 04-Nov-2024, PreQC No. ASMJ-24-15413(PQ); Reviewed: 14- Nov-2024, QC No. ASMJ-24-15413; Revised: 18-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. ASMJ-24-15413(R); Published: 30-Nov-2024