Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Strategic Orientation and Organisational Commitment on Co-Operative Performance in Malaysia: A Conceptual Framework

Mohamad Haswardi Morshidi, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Haim Hilman, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Yusmani Mohd Yusoff, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

Contemporarily, Strategic Orientation (SO) and co-operative sector have become essential topics among business academics and practitioners. This study investigates Strategic Orientation (SO) and Organisational Commitment (OC) on co-operative performance. In this study, SO’s components are Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), and Learning Orientation (LO). Despite the importance of SO, research works that link these concepts to co-operative performance are very limited. In this regards, this study has discovered a positive relationship between SO and co-operative performance through extensive literature view, and has developed a conceptual model for empirical validations. This study serves not only to clarify the effects between SO and OC, but also explains the effects of OC on co-operative performance, which most studies have neglected. As a unique organisation, co-operatives have an advantage over other businesses, especially by applying the OC in co-operative activities to enhance co-operative performance significantly.

Keywords

Co-operative Performance, Strategic Orientation, Organisational Commitment, Co-operative

Introduction

In Malaysia, the cooperative movement has existed for almost a century since 1922. Before 2008, the development of the co-operative movement could only be measured in terms of the number of co-operatives, their members, share capital, and assets. After 2008, the co-operative sector began to contribute positively to the development of the country. However, compared to the movement of co-operatives in other countries, particularly in western nations, the position of local co-operatives remains difficult to predict, except for several large co-operatives.

The recognition of co-cooperatives as the third sector is a critical national priority. The co-operative sector has become a leading part of the economy and has demonstrated a significant impact on millions of Malaysians (Janudin et al., 2016). Several studies reported that co-operatives in Malaysia show low performance (Hadzrami et al., 2017) and the total turnover of Malaysia’s co-operatives is still low; as of 2018, the total turnover was RM40.318 billion (Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission, 2019). In comparison, co-operative turnover was far behind Small And Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs), with RM521.7 billion, contributing to 37.4 percent of GDP in the same year (BH Online). The 2016 contribution to Malaysia’s GDP showed poor performance (Shakir et al., 2020). Despite this, the National Cooperative Policy (2011–2020) anticipated that co-operatives would be contributing approximately 10% of the National output by 2020 (Saleh & Hamzah, 2017; Shakir et al., 2020). More importantly, Malaysian co-operatives’ turnover as of December 2018 from 281 large co-operatives contributed to 94.64 percent compared to that of 11,832 micro co-operatives and 1,589 small co-operatives, each contributing 0.73 percent and 1.63 percent to the total revenue, respectively (Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission, 2019). Researchers have recently shown an increased interest in co-operatives and the problem has been extensively addressed within the research community. Studies conducted in the context of co-operatives include research on competitive strategies (Figueras & Garuz, 2019), the impact of brand equity (Grashuis, 2018), presidency of the governing board of directors (Esteban-Salvador et al., 2019), etc. Co-operatives, being unique compared to other businesses, are defined as “people-centred enterprises owned, controlled, and run by and for their members to realise their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations” (International Co-operative Alliance). A closer look at the review reveals that the co-operative model has grown significantly since its introduction in 1844. It is now estimated that the sector has approximately 1 billion members and directly or indirectly employs 250 million people worldwide (ICA, 2017). Co-operatives are internationally recognised business organisations owned by their members in a democratic way (International Co-operative Alliance, 2005; Zeuli & Cropp, 2004).

Different definitions have been given for the co-operative movement, but overall, they have the same meaning. During the International Co-operative Alliance’s (ICA) Centenary in Manchester in 1995, the ICA issued the Co-operative Identity Statement, outlining the core values and a revised set of co-operative principles (ICA, 2017). The definition of co-operative declared at the time is as below:

“A co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.”

The majority of co-operatives will eventually struggle to survive because members may lack trust, commitment, and loyalty to their respective co-operative due to the lack of knowledge about co-operatives (Kinyuira, 2017). Tadesse & Kassie (2017) identified marketing co-operatives in rural Ethiopia and discovered that several farmers lacked trust in their co-operatives, lacked trust within their co-operatives, and were not fully committed to their co-operatives. Similarly, a co-operative study in Africa showed poor performance because of a lack of trust and commitment (Bernard et al., 2010).

Strategic orientation has become a central issue for business organisations in the new global economy. Academic attention has been drawn to the strategic orientation from various research fields, including management, technology, marketing, and entrepreneurship (Didonet et al., 2020; Hakala, 2011; He et al., 2020). Narver & Slater (1990) defined Strategic Orientation (SO) as “the strategic direction implemented by a firm to produce behaviours conducive to the continuous superior performance of the business.”

Strategic orientation is a well-thought-out concept and is usually applied for business performance in business literature (Mamun et al., 2018). Over the last 30 years, Strategic Orientation (SO) studies have emerged gradually. SO studies continue to be relevant and evolve in different orientations, either individually or in conjunction with other orientations (Fahim & Baharun, 2017). A detailed examination by Cássia & Zilber (2016) demonstrated that SO is a series of guiding principles that can shape decision-making management and help managers configure organisational resources and interact with the market effectively. However, strategic focus as a core concept has so far been given more importance in strategic management, marketing, and business literature (Aloulou & Fayolle, 2005; Aloulou, 2019).

Co-operative Contribution to the Malaysian Economy

This study aims to contribute to this growing field of research by looking into the Malaysian co-operative movement. The co-operative movement is critical to economic development. While there has been an increased recognition that more attention should be paid to co-operatives in Malaysia, there are still few studies on the subject (Azmah et al., 2012; Shakir et al., 2020). In addition, the performance of co-operatives in Malaysia has been impressive and the co-operative movement is the third-largest industry contributing to the economy (Abd Rahman & Zakaria, 2018; Hammad Ahmad Khan et al., 2016; Hasbullah et al., 2014); but in comparison to public and private businesses, co-operatives continue to lag in growth (Aris et al., 2018). Based on the statistics in Table 1, the significant contributors to the turnover of Malaysia’s co-operatives ending in December 2018 were 94.64 percent from 281 large co-operatives, compared with those from 11,832 micro co-operatives and 1,589 small co-operatives, each contributing 0.73 percent and 1.63 percent of the total revenue, respectively. For the Malaysian co-operatives, the total turnover for 2018 was RM40.318 billion (Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission, 2019). For comparison, the Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) contributed RM521.7 billion, or 37.4% of the country’s GDP in the same year (BH Online). Furthermore, banking, credit/finance, agriculture/plantation, housing, industries, consumers, construction/development, transport, and services are among the nine functions classified by Malaysian co-operatives, based on the nature of their business activities. Details are shown in Table 1, Statistic Co-operative Movement in Malaysia (2014–2018) by Total Co-operative, Membership, Shares, Assets, and Turnover.

| Table 1 Statistic Co-Operative Movement in Malaysia (2014 – 2018) by Total Co-Operative, Membership, Shares, Assets, and Turnover |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particular/Year | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| Total Co-operative | Large | 281 | 274 | 258 | 262 | 186 |

| Medium | 545 | 586 | 571 | 557 | 507 | |

| Small | 1,589 | 1,520 | 1,407 | 1,317 | 289 | |

| Micro | 11,832 | 11,519 | 11,192 | 10,633 | 9,889 | |

| Total | 14,247 | 13,899 | 13,428 | 12,769 | 10,871 | |

| Membership | Large | 2,883,411 | 2,947,495 | 2,986,286 | 3,210,047 | 2,918,955 |

| Medium | 582,855 | 679,444 | 824,449 | 888,144 | 1,009,857 | |

| Small | 1,076,700 | 1,104,140 | 1,048,674 | 1,112,988 | 1,168,862 | |

| Micro | 1,517,766 | 1,822,518 | 2,206,813 | 2,280,012 | 2,311,873 | |

| Total | 6,060,732 | 6,553,597 | 7,066,222 | 7,491,191 | 7,409,547 | |

| Shares (Billion) | Large | 13,004.33 | 12,420.36 | 12,181.89 | 11,916.23 | 10,762.32 |

| Medium | 1,230.20 | 1,342.80 | 1,144.40 | 1,282.37 | 1,699.50 | |

| Small | 361.80 | 308.79 | 323.31 | 308.50 | 647.90 | |

| Micro | 304.69 | 276.20 | 342.24 | 304.41 | 358.33 | |

| Total | 14,901.02 | 14,348.15 | 13,991.84 | 13,811.51 | 13,468.05 | |

| Assets (Billion) | Large | 137,097.33 | 134,248.27 | 125,341.71 | 116,495.43 | 109,924.49 |

| Medium | 3,162.39 | 3,148.70 | 2,991.83 | 3,440.54 | 4,125.17 | |

| Small | 1,460.36 | 1,266.22 | 1,247.40 | 1,154.27 | 1,653.87 | |

| Micro | 1,138.80 | 1,012.98 | 1,159.74 | 2,186.55 | 1,084.16 | |

| Total | 142,858.88 | 139,676.17 | 130,740.68 | 123,276.79 | 116,787.69 | |

| Turnover (Billion) | Large | 38,160.33 | 38,000.91 | 37,550.56 | 31,511.63 | 33,074.20 |

| Medium | 1,205.75 | 1,315.94 | 1,260.36 | 1,224.92 | 1,068.21 | |

| Small | 657.32 | 627.97 | 570.32 | 539.98 | 530.27 | |

| Micro | 294.74 | 296.79 | 283.39 | 281.35 | 278.30 | |

| Total | 40,318.14 | 40,241.61 | 39,664.63 | 33,557.88 | 34,950.98 | |

(Source: Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission, 2019)

| Table 2 Co-Operative Scale Based on Turnover |

|

|---|---|

| Micro | : Turnover of less than RM200,000 |

| Small | : Turnover between RM200,000 and less than RM 1 million |

| Medium | : Turnover between RM 1 million and less than RM 5 million |

| Large | : Turnover of more than RM 5 million |

Literature Review

Co-operative Performances

First, this paper provides a brief overview and discusses the literature on co-operative performance in the field, and in a later section, a summary of Strategic Orientation (SO) and Organisational Engagement (OC).

Performance themes often draw attention to different management divisions, including strategic management (Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986). The co-operative concept with multiple interpretations is still under debate (Soboh et al., 2009). The performance of the co-operatives may be helpful if the services provided to their members are better than those offered by a non-cooperative business firms (Soboh et al., 2009). Mayo (2011, 162) defined co-operative performance as “the delivery of value to members over time and at least cost.”

Financial and non-financial performance are the two dimensions most commonly used to measure performance. There is a substantial amount of literature on co-operative performance. Several evidence suggests that when it comes to co-operative performance, most publications use the performance of the co-operative or the performance of the co-operative member as the outcome variable (Grashuis & Ye, 2019). A study conducted by Janudin, et al., (2016) demonstrated that performance measurement system practices are still lacking among co-operatives. In previous studies, several studies showed that co-operative performance is measured in two main categories, where the profitability ratio is the first category and the efficiency ratio reflects the capacity and efficiency of equity capital to generate co-operative returns (Huang et al., 2015; Shamsuddin et al., 2018). Aris, et al., (2018) identified the ability of co-operatives in maintaining their performance based on financial ratios, including profitability, efficiency, and solvency.

According to thorough research and studies, most studies used and focused on financial ratios, regarded as performance indicators. Financial ratios provide essential information on funding activities, operating costs, business stability, and the user’s information needs (Shamsuddin et al., 2018). However, according to Mayo (2011), it should be noted that social elements, including innovators, are also included in measuring co-operative performance: services, welfare and membership activities, and community benefits with added value to stakeholders. Non-financial ratios, according to Beaubien & Rixon (2012), include staff profile, community investment, members, and the environment.

To date, various methods have been developed and introduced for measuring co-operative performance. According to Shakir, et al., (2020), in most recent co-operative studies in Malaysia, the seven items applied to represent the financial and social dimensions are net income, gross profit, net profit, annual sales, profit-based internal financing, dividend pay-out, and social responsibility. Various authors have measured co-operative performance in different ways. A study on an oil palm co-operative in Malaysia by Zakaria, et al., (2019) argued that co-operative performance should be reflected by revenue and productivity or the yield from oil palm plantation. Hammad Ahmad Khan, et al., (2016) conceptualised co-operative performance in terms of intangible assets, such as intellectual capital and member involvement in co-operatives. Also, according to Shamsuddin et al., (2018), co-operative performance in the United States and Europe is mostly measured using regression analysis to compare financial performance ratios, such as profitability, productivity, liquidity, leverage, and asset efficiency.

There has been a renewed interest in co-operative performance in recent years. Regrettably, recent studies on co-operative performance in Malaysia have revealed that co-operatives continue to make a minimal contribution (Hadzrami et al., 2017; Rasid, 2018; Shakir et al., 2020). The sustainability and progress of the co-operative movement are dependent on the performance of co-operatives (Othman et al., 2014). However, the contribution of the co-operatives to the Malaysian economy is accepted and more crucial than ever before (Shamsuddin, 2015).

In Malaysia, the INDEX 100 Best Co-operatives of Malaysia is provided by the Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission (MCSC). A successful co-operative is on the list of the 100 Best Co-operatives in Malaysia if it attains satisfactory financial performance, business, management, and legal compliance by the MCSC standards and the criteria used by the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA). The Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission uses INDEX 100 as a method of performance measurement to recognise the best Malaysian co-operatives through an annual quantitative and qualitative evaluation process. However, in a study on the performance of co-operative in Malaysia by Othman, et al., (2014), only 19.6% of the groups have achieved the highest efficiency scores among 56 co-operative groups in the country based on Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA); thus, the result revealed that co-operative groups have not been operating at their most productive or optimal scale. They need to find ways to improve so that the co-operative sector can spearhead more contributions to the national economy (Hasbullah et al., 2014).

The performance of co-operatives should be studied from two angles, namely financial and non-financial aspects, based on the review by previous studies on the performance of the co-operatives discussed above. Therefore, besides focusing on financial performance, Mayo (2011) highlighted the measurement of co-operative performance based on social elements, including innovators: members’ services, welfare and activities, and community benefits with added value to stakeholders. In addition to meeting the co-operative’s objectives, the co-operative should continually strive to improve its performance to achieve market success. Therefore, co-operative performance measures for this concept paper will be studied from the financial and non-financial perspectives, as many researchers have recommended that non-financial and financial measurement tests should include performance dimensions (Brosens et al., 2007; Gronum et al., 2012; Hilman & Kaliappen, 2014). Therefore, the proposed SO conceptual framework is intended to examine the relevance of the SO and OC dimensions to co-operative performance in Malaysia.

Strategic Orientation (SO)

In the new global economy, strategic orientation has become a central issue for business organisations. Strategic orientation has received academic attention in a variety of research areas, including management, technology, marketing, and entrepreneurship (Didonet et al., 2020; Hakala, 2011; He et al., 2020). Recent evidence suggests that different strategic orientation definitions exist, but strategic orientation’s objective remains the same, whether to improve performance or to achieve superior performance (Ogbari et al., 2018). Narver & Slater (1990) defined Strategic Orientation (SO) as “the strategic direction implemented by a firm to produce behaviours conducive to the continuous superior performance of the business.” Meanwhile, Stevenson (1983) defined strategic orientation as a business dimension that refers to the factors influencing how a company’s strategy is developed. In comparison, Hakala (2011) defined strategic orientations as values, procedures, practices, and decision-making styles that influence business operations and generate the desired behaviours to ensure their viability and performance. With these definitions of strategic orientation, the co-operative needs to identify the factors that lead to the formation and formulation of the best performance strategy.

Most SO studies have suggested that, taken individually, these strategic orientations are critical to a company’s success, but they are rarely studied together in the literature. Several recent studies have attempted to accomplish this (Hakala, 2010, 2011; Presutti et al., 2019; Schweiger et al., 2019). In response, Wales, et al., (2019) opined that a smart combination (or merger) of multiple orientations can provide a strong foundation for business performance improvement and growth, instead of relying on a single strategic orientation. Discussions continue on SO’s best orientation, and studies have shown that various combinations of orientations can enable companies to perform better if only one orientation is emphasised separately (Boso et al., 2012; Ho et al., 2016).

More recently, contradictions have emerged in the literature about the most individually conceptualised SO variables, such as EO (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Onwe, 2020; Johan Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005; Zainol Ayadurai, 2011), MO (Hilman & Kaliappen, 2014; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Morgan & Strong, 1998), and LO (Tajeddini et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2008). Several attempts have been made to study SO, and the strategic orientation variables have also been conceptualised as more than one orientation or factor (Jha & Bhattacharyya, 2013; Laukkanen et al., 2013; Song & Jing, 2017). Previous studies have reported that SO have more than one factor and dimension to conduct (Cadogan, 2012; Laukkanen et al., 2013). A lack of more complex multidimensional approaches to strategic orientation with a holistic approach has resulted from research into a single orientation (Hakala, 2010).

A substantial amount of literature has been published on SO. Such studies were carried out using the various orientation variables and strategy dimensions. The current literature with regard to the impact of strategic orientation on organisational performance has some flaws (Pollanen et al., 2017). Several studies investigating SO in co-operatives found that the key to success is strategy. Co-operatives need to strategize to optimise their performance and achieve optimum economic performance in their business activities (Figueras & Garuz, 2019; Yun et al., 2019). The purpose of this paper is to assess and confirm the need to understand SO studies and what leads them to determine the variables that fit the strategic orientation of a co-operative.

In the last four decades, rapid progress has been made in SO but has yet to be proposed, and the theoretical and empirical focus is still being given to Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), and Learning Orientation (LO) (Hakala, 2011). The three most accepted commonly cited strategic orientations are increasingly difficult to ignore, since they have a significant impact on performance: market orientation, entrepreneurial orientation, and learning orientation (Hakala, 2011; Krzakiewicz & Cyfert, 2019). Thus, the paper will concentrate on three strategic orientation dimensions: entrepreneurial orientation, marketing orientation, and learning orientation toward co-operative performance.

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)

A large number of published studies have explained the role of entrepreneurial orientation (EO). Mintzberg (1973) defined strategy-making as an entrepreneurial approach characterised by an active search for new opportunities, as well as dramatic leaps forward in the face of uncertainty, and strategic management literature has extensively studied entrepreneurship (Mthanti & Ojah, 2017). Miller (1983) pointed out EO as follows: “an entrepreneurial firm engages in product-market innovation, undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come up with ‘proactive’ innovations, beating competitors to the punch.” Later, Lumpkin & Dess (1996) argued that EO practices from the management style of top management in the organisation, is the capacity of top managers to take more risks and take an innovative and proactive management philosophy to the organisation’s strategic decision-making activities.

EO perhaps refers to an organisation’s strategic orientation and takes on particular business aspects of decision-making, methodology, and practice (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). In another major study, Miller (1983) used EO as a three-dimensional construct of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness. A recent study by Pearce, et al., (2010) defined EO as a set of unusual but linked behaviours that include qualities like proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, risk-taking, and autonomy. Detailed examination of EO by Anderson, Kreiser, Kuratko, Hornsby & Eshima (2015) introduced a new EO concept in line with Miller/Covin and Slevin’s, which involves only three dimensions of entrepreneurial behaviour (innovative and proactive) and the tendency of managers toward strategic decision-making in favour of risk-taking (risk-taking).

A large and growing body of literature has reflected the dominance of EO in the context of entrepreneurship in terms of its methodological robustness. At different levels of analysis, several studies investigating the EO were performed, i.e., both at the organisational level (Aljanabi et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2019; Habib et al., 2020; Onwe, 2020) and the individual level (Guzmán et al., 2019; Mantok et al., 2019; Sabahi & Parast, 2020). For example, while such studies examined entrepreneurial orientation at the individual level, such as Jalilvand, et al., (2019); Guzmán, et al., (2019); Mabula, et al., (2020), others like Asemokha, et al., (2019); Dirgiatmo, et al., (2019); Mamun, et al., (2018) undertook the variable at the organisational level.

Overall, many researchers found that entrepreneurial orientation plays a valued role in organisational efficacy. Additionally, numerous research studies on various aspects of leadership and organisational effectiveness have established a strong correlation between entrepreneurial orientation and organisational efficiency in different countries. These, amongst others, included Nigeria (Onwe, 2020), Bangladesh (Habib et al., 2020), Spain (Guzmán et al., 2019), the United States (Gupta et al., 2019), Iraq (Aljanabi et al., 2019), India (Mantok et al., 2019), Finland (Asemokha et al., 2019), Iran (Jalilvand et al., 2019), and China (Mu et al., 2017). Previous studies have reported on entrepreneurship research itself, while EO has also been studied in tandem with various groups of organisational variables and issues, amongst which are the efficacy on retail business (Sellappan & Shanmugam, 2020), the influence of owners (Harris & Ozdemir, 2020), green supply chain management practices (Habib et al., 2020), co-operative principles (Guzmán et al., 2019), interaction orientation (Song et al., 2019), etc.

So far, however, a few studies on EO have been done in Malaysia. Recently, researchers have shown interest in EO, but most EO studies in Malaysia focus on other sectors, such as SMEs (Bakar et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2017; Zakaria et al., 2017) and the government sector (Arshad et al., 2015; Musa et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the issue has grown in importance in light of the recent study on EO in co-operatives. For instance, Musa, et al., (2014) examined five constructs of EO and business performance on co-operatives but only in Malaysia’s northern region.

Even though most of these researchers concentrated on the three dimensions of EO (i.e., innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking), Rezaei & Ortt (2018) opined that in these relationships, the separate dimensions of EO (innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking) may play various roles. The three most popular three-dimensional constructs of innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness, as have been used in previous EO studies, are the dimensions considered for this model.

Market Orientation (MO)

A substantial amount of literature has been published on MO. There are several MO definitions in marketing, but they are mutually exclusive (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990; Narver & Slater, 1990; Wales et al., 2020). The study by Narver & Slater (1990) on MO shows the important cultural phenomenon of an organisation that develops effective behaviours significant for creating superior customer value and continuous superior organisational-performance. Kohli & Jaworski (1990) defined MO from the behavioural perspective as follows: “the organisation-wide generation of market intelligence about current and future customer needs, dissemination of intelligence across departments, and organisation-wide responsiveness to it.” The issue has grown in importance in light of recent findings, designating a strategic orientation intended to develop “the necessary behaviours for creating superior value for buyers and, thus, continuous superior performance for the business” (Narver & Slater, 1990).

Kajalo & Lindblom (2015) showed that two well-known conceptualisations of MO had been given by Narver & Slater (1990); Kohli & Jaworski (1990). Kohli & Jaworski (1990) focused on MO from market intelligence (internal and external) in another significant study. Kohli & Jaworski’s (1990) concept was adopted from a marketing concept and places greater emphasis on customers. Narver & Slater (1990) identified that to implement the marketing concept, MO can be viewed in cultural terms with regard to customer orientation, competitor orientation, and inter-functional coordination. Narver & Slater (1990) asserted that individuals play a critical role in defining MO as an organisation’s culture that places a premium on customers and competitors.

In 2014, Hilman and Kaliappen published a paper describing MOs, providing superior information on current and future markets, improving security, and improved capacity to respond adequately to changes in the market. Morgan & Hunt (1999) interpreted MO as a decision-making resource which refers to strategic trends and operations at the firm level to create value for customers.

Many studies have argued that market-oriented culture is a critical determinant for business enhancement because customer needs, desires, and preferences are recognised, and market-oriented organisations strive for better customer satisfaction, which will indirectly improve business performance (Iyer et al., 2020; Mamun et al., 2018; Sampaio et al., 2019; Shamsudin & Hassim, 2020). According to Wales, et al., (2020), MO refers to the strategic tendencies and firm-level activities of generating superior customer value. Migdadi, et al., (2017) offered a comprehensive conceptual framework that includes MO beside Knowledge Management Processes (KMP) and the mediating role of innovative capacity on organisational performance of 210 Jordanian manufacturing and service organisations. The study results revealed that MO can lead to better innovation capability in the organisations, leading to better organisational performance. However, Song & Jing (2017) concluded that the relationship between the strategic orientation and performance in Beijing revealed that exploitation–market orientation does not directly have an impact on the performance of 199 New Chinese Ventures.

Furthermore, the strength of market orientation has also been seen in previous research, where the explanation of market orientation towards performance received attention from reviewers in various regions worldwide such as Bangladesh (Habib et al., 2020), the United States (Iyer et al., 2020), Western Europe (Fernandes Sampaio et al., 2020), India (Farooq & Vij, 2019), Indonesia (Syahdan et al., 2020), Jordan (Migdadi et al., 2017), Iraq (Abed et al., 2018), and Sweden (Sundström & Ahmadi, 2019). Market orientation has also been studied in tandem with various groups of organisational variables, issues, and contexts, amongst which are the hotel industry (Fernandes Sampaio et al., 2020), brand management (Iyer et al., 2020), knowledge management orientation (Farooq & Vij, 2019), the banking sector (Abed et al., 2018), transformational leadership (Hakimi et al., 2019), etc.

It is generally agreed that not many MO studies have been done in Malaysia. Several local attempts have been made on MO studies in manufacturing companies (Amin et al., 2016; Mamun et al., 2018; Xian et al., 2018), supply chain management (Yusoff et al., 2016), strategic orientation (Nasir et al., 2017), and total quality management and organisational culture in SMEs (Ali et al., 2017).

Through review of the MO, this study aims to shed new light on these discussions in the context of co-operatives in Malaysia. Nonetheless, the researcher would not go into great detail on MO in co-operative settings. Most MO’s perspectives are based on Narver & Slater's (1990); Kohli & Jaworski's (1990) views that are closely associated and popular. Yet, the impact of MO on co-operative performance in Malaysia is still unclear. Although these concepts have enormous advantages for all MO researchers, specific differences can be drawn from among them; therefore, this is in line with Narver & Slater's (1990) view. The study considers MO of three dimensions: customer orientation, competitor orientation, and inter-functional coordination, all of which can result in better organisational performance.

Learning Orientation (LO)

One important aspect of learning is the development of employees through improved skills and knowledge (Nurn & Tan, 2010). Little agreement has been reached on how LO relates to the company’s continual tendency of questioning existing business, environmental assumptions, and beliefs, as well as the ability to communicate organisational changes (Wales et al., 2020). In 1997, Sinkula et al. defined LO as a set of organisational values which influence the proactive knowledge production of interpreting, assessing, accepting, or rejecting information. It causes individuals to have routines related to learning commitment, open-mindedness, and shared vision. Liao et al., (2017) defined LO as an organisational process for enhancing personal knowledge by integrating it into the knowledge system.

The LO is considered a resource and an organisational capability that supports companies in developing their competitiveness and organisational performance (Vega Martinez et al., 2020). LO is conceptualised as a “set of organisational values that influence the firm’s propensity to create and use knowledge” (Sinkula et al., 1997). Previous studies reported and examined LO as the driver of strategic advantage, leading to continuously improved performance (Mohd Shariff et al., 2017; Sawaean & Ali, 2020). Wales et al., (2020) stated the idea that a firm must assume and believe in itself and its environment to adapt appropriately. LO is a concept about the creation and the use of knowledge within an organisation, which lead to a competitive advantage (Calantone et al., 2002), while Baba (2015) identified LO as a collective capacity derived from the process of cognition and experience, which includes knowledge acquisition, exchange, and use.

There is an increasing interest in LO from multidisciplinary international reviewers. These, amongst others included those from the United Kingdom (Kumar et al., 2020), Tanzania (Mabula et al., 2020), Kuwait (Sawaean & Ali, 2020), Mexico (Vega Martinez et al., 2020), Qatar (Nair, 2019), Yemen (Homaid et al., 2018), Thailand (Kaliappen et al., 2019), Indonesia (Syahdan et al., 2020), and China (He et al., 2018). Many LO debates take place with various groups of organisational variables, issues, and contexts, amongst which are SMEs (Kaliappen et al., 2019; Mabula et al., 2020; Sawaean & Ali, 2020; Syahdan et al., 2020; Vega Martinez et al., 2020), microfinance (Homaid et al., 2018), the hotel industry (Nair, 2019), manufacturing firms (Kumar et al., 2020), etc.

LO has often been studied as a mediator, even if there are a direct causes and effects. Research demonstrated that LO mediates the exploration activities by managers to encourage individual unlearning (Matsuo, 2020), organisational innovativeness, financial performance, production performance, marketing performance (Kaliappen et al., 2019), market and entrepreneurial orientation on the performance (Homaid et al., 2018), the effect of CSR programme on SMEs’ Performance (Ratnawati et al., 2018), and post-entry performance of international new ventures (Gerschewski et al., 2018). Several studies revealed that although it does not play the role as a mediator, LO still shows a mediating effect (Gerschewski et al., 2018; Homaid et al., 2018; Matsuo, 2020), and partial mediation (Gerschewski et al., 2018; Ratnawati et al., 2018).

To date, research has tended to focus on LO as a mediator role, and it is generally agreed that not many LO studies have been conducted in Malaysia. Locally, LO studies have been done in agricultural studies (Fahim & Baharun, 2017) and SMEs in export markets (Ismail, 2016; Ismail et al., 2018). It has been demonstrated conclusively that the LO component encompasses a commitment to learning, a shared vision, and open-mindedness; LO represents the extent to which a firm’s existing beliefs and assumptions can be challenged through organisational learning and knowledge integration (Sinkula et al., 1997; Wales et al., 2020).

Organisational Commitment (OC)

During the past 40 years, much more information has become available on OC. In 1977, Steers defined OC as the degree to which an individual identifies with and participates in a specific organisation (Amernic & Aranya, 2005). Ten years later, O'Reilly (1989) defined OC as a person’s psychological connection to the organisation, which includes a sense of engagement in the job, loyalty, and belief in the organisation’s values. Preliminary work on OC was undertaken by Porter et al., (1974). Three dimensions of OC may be distinguished: (a) a strong belief in, and acceptance of, the organisation’s goals and values; (b) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organisation; and (c) a definite desire to maintain membership in the organisation. However, another major study by Allen & Meyer (1990) found that the OC has a psychological condition that characterises the employees’ relationship with the organisation. Nevertheless, Camilleri & Van Der Heijden (2007) pointed out that although different definitions and measures of OC appear to exist, they do share a typical proposal that OC is seen as an individual’s relationship with the work organisation.

OC is another work-related attitude considered to be important in this study. A study carried out by Mowday, et al., (1982) indicated that the phenomenon produces good results for the individual and the organisation when there is a high level of individual commitment to the organisation. It seems that Mowday, et al., (1982) perceived OC as an individual’s attitude towards one’s organisation that involves strong trust and acceptance of the objectives and values of the organisation, with eagerness to make significant efforts for the organisation. More recent arguments against OC have been conceptualised by Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran (2005), referring it as a psychological state or mindset that binds individuals to a course of action relevant to one or more targets and a willingness toward persistent action.

In previous research, several attempts have been made to analyse OC, which has received attention from reviewers in different countries around the world, and has been studied along with a variety of organisational variables, issues and contexts, including Internal Market Orientation (Yu et al., 2019) in China, Internal Marketing (Chiu et al., 2019) in Taiwan, Co-operative Difference (Marcoux et al., 2018) in Canada, Person-Organisation Fit (Jin et al., 2018) in the United States, Learning Orientation (Del Carmen Martínez Serna et al., 2018) in Mexico, Job Satisfaction (Silitonga et al., 2017; Yousef, 2017), Attitudes toward Organisational Change (Yousef, 2017) in United Arab Emirates, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organisational Culture on Job Satisfaction (Soomro & Shah, 2019) in Pakistan, etc.

In previous studies, OC’s role as a mediator has been widely investigated. Studies in which OC is a mediator are between Members’ Trust and Participation in the Governance of Co-operatives (Barraud-Didier et al., 2012), Internal Marketing and Job Performance (Chiu et al., 2019), Internal Market Orientation and Employee Retention (Yu et al., 2019), Job Satisfaction and Organisational Change (Yousef, 2017), Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organisational Performance (Gede Supartha & Nugraheni Saraswaty, 2019), and Testing the Theories of Person-Organisation Fit and Organisational Commitment Through a Serial Multiple Mediation Model (Jin et al., 2018). The following subtopic discusses the dimensions of Organisational Commitment (OC).

Relationship EO, MO, LO, OC and Co-operative Performance

The positive relationship between EO and organisational performance is also well recognised (e.g., Aljanabi et al., 2019; Hughes et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). The research findings in a study by Alvarez-Torres, et al., (2019) on 170 SMEs operating in the Bajio Region (México) in the leather–footwear sector confirmed an association between EO and business performance, which corroborates previous studies. Most studies proved that there is a positive relationship between EO and performance. However, a negative correlation was detected in highly uncertain and turbulent economic environments (Pratono & Mahmood, 2015). Evidence concerning EO-level relationships has remained inconsistent despite the popularity of EO-Research in strategic management and enterprise literature (Seo, 2019).

Given the summary of previous studies’ findings, it can be established that MO has a positive impact on organisational performance (Beliaeva et al., 2018; de Guimarães et al., 2018; Didonet et al., 2020; Migdadi et al., 2017). Although through a meta-analytical study, Kirca et al., (2005) summarised empirical findings and concluded that MO has a positive impact on performance. In the meta-analytical study by Ellis (2006), non-significant or negative relationships were found. Homaid, et al., (2018) study on 166 branch managers of Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) in Yemen, resulted in a negative significance between MO and performance.

The positive relationship between LO and organisational performance is also well known (e.g., Lestari et al., 2018; Sirivariskul, 2020). Baker & Sinkula (1999) discovered a strong correlation between learning orientation and business performance. The learning orientation has been suggested as a prerequisite for effective organisational learning to influence performance (Santo-Vijande et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2018). Previous research has found that learning orientation is an important factor in improving performance (Huang & Li, 2017; Real et al., 2014). There has also been a study which found that learning does not necessarily improve performance or that there is no positive relationship between them (Crossan et al., 1999).

Chiu, et al., (2019) study on 254 employees at each of Taipei City’s 12 municipal sports centres found that organisational commitment has a positive effect on job performance. It acts as a partial mediator between internal marketing and job performance. Also, Jaramillo, et al., (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of studies conducted over the last 25 years in 14 countries and discovered a positive but tenuous relationship between organisational commitment and a salesperson’s job performance. Meyer, et al., (2002) discovered mixed relationships between organisational commitment and job performance in a meta-analytical study.

Evidence suggests that strategic orientation can foster organisational commitment; a positive relationship has been discovered between career commitment and strategic orientation, i.e., learning and goal orientation (Kerdpitak & Boonrattanakittibhumi, 2020). A study also showed that HR organisational commitment is strongly related to strategic orientation (Ogunyomi & Bruning, 2016). Managers, as well as employees, must see the commitment to learning as a value that creates competitive advantages. A shared vision explains that management is responsible for the LO (Vega Martinez et al., 2020).

Mediation Role of Organisational Commitment (OC)

Although organisational commitment has been studied extensively, empirical research is still limited in emerging economies (Vega Martinez et al., 2020). Organisational commitment is an organisational psychological condition correlated with many organisations and behavioural outcomes (Klein, 2012). Recently, Chiu, et al., (2019) has proposed that organisational commitment mediates the relationship between internal marketing and job performance. As a result, organisational commitment has a positive impact on job performance and serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between internal marketing and job performance.

The findings based on data from three different managerial respondents in 275 Chinese companies show that Internal Market Orientation has a precedential effect on corporate performance through employee commitment and retention (Yu et al., 2019). A recent study in the co-operative context by Gede Supartha & Nugraheni Saraswaty (2019) on impacts of entrepreneurial leadership on organisational performance of credit co-operative in Bali Indonesia, discovered that OC has a positive and significant correlation with organisational performance. Also, OC plays the role as a partial mediator in entrepreneurial leadership’s influence on organisational performance.

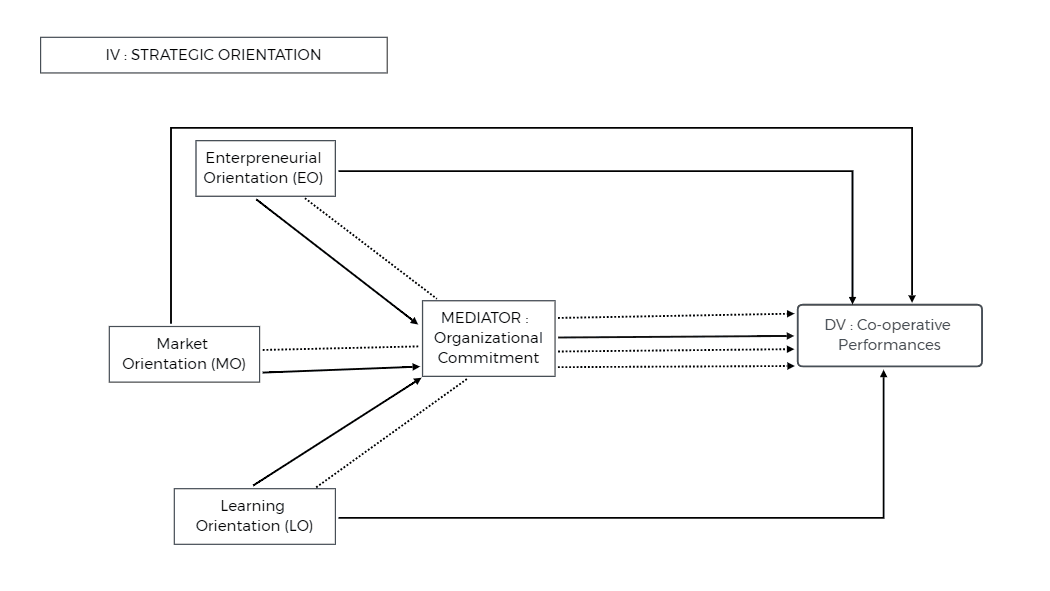

Conceptual Framework

Based on the reviewed literature, the following conceptual model is developed to explain the relationship among the variables of the study.

Figure 1: Relationship Strategic Orientation, Organisational Commitment, and Co-Operative Performance

From the framework above, it is therefore likely that such a relationship exists between SO (EO, MO, & LO), OC, and performance in a co-operative context. According to Yun, Ina, and Umi (2019), co-operative performance is influenced by strategy. Based on the above arguments and literature reviewed, the following proposition is proposed:

i. Proposition 1: Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), Learning Orientation (LO), and Organisational Commitment (OC) affect Co-operative Performance.

ii. Proposition 2: Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), and Learning Orientation (LO) have a significant effect on Organisational Commitment (OC).

iii. Proposition 3: Organisational Commitment (OC) significantly mediates the relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), Learning Orientation (LO), and Co-operative Performance.

This framework is expected to contribute to the body of knowledge by confirming the relationship between study design and mediation. Specifically, this study explores the impact of strategic orientation (i.e., entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, and learning orientation), and organisational commitment towards co-operative performance. As has been shown to date, the literature review demonstrated that although EO, MO, LO, and OC have been extensively discussed in previous research, little empirical work has shown an empiric attempt to operationalise EO, MO, and LO to measure co-operative performance. Besides that, OC worked as a mechanism to facilitate the translation of EO, MO, and LO into co-operative performance and provided a theoretical contribution to OC’s potential mediation effect. The introduction of OC as a mediator was a very new attempt of its kind. The role of OC as a mediator has not been much discussed before, either in the general case or in the specific case of EO-performance relationship, MO-performance relationship, and LO-performance in the Malaysian co-operative context. Therefore, this framework will extend the scope of the existing literature on variables in this study and their relationship.

Conclusion

This conceptual paper aims to outline a comprehensive model of SO and OC, as conducted in co-operatives in Malaysia. In this challenging economic environment, co-operatives are particularly affected by poor business performance. Therefore, co-operatives should develop strategies to improve performance. In the literature, authors have made great efforts to explore SO’s role in shaping business performance. In this case, an applied orientation approach is strategic orientation consisting of Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Market Orientation (MO), and Learning Orientation (LO) elements that can have a positive impact on performance from previous studies in other contexts (Arshad et al., 2015; Bakar et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2017; Musa et al., 2017; Zakaria et al., 2017) and even co-operatives (Musa et al., 2014). Empirical studies may further validate the conceptual framework. Mostly, it is worthwhile to examine how the SO and OC will change and improve Malaysia’s co-operative performance. Testing the OC as a mediating role in future studies may also be recommended. Thus, if the co-operative’s economic and social activities do not ignore the OC, Malaysia’s co-operative efficiency may improve. Therefore, to further enhance co-operative efforts, achieve any government co-operative development plan (Othman et al., 2014), improve sustainability, and increase performance, co-operatives have to ensure that they adhere and practise OC in their business activities.

References

- Abd-Rahman, N., & Zakaria, Z. (2018). Cooperative management efficiency in Malaysia. Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS), 3(2), 134.

- Alani, E., Kamarudin, S., Alrubaiee, L., & Tavakoli, R. (2019). A model of the relationship between strategic orientation and product innovation under the mediating effect of customer knowledge management. Journal of International Studies, 12(3), 232–242.

- Aljanabi, A.R.A., Hamasaleh, S.H., & Mohd Noor, N.A. (2019). Cultural diversity and operational performance: Entrepreneurial orientation as a mediator. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(9), 1522–1539.

- Aloulou, W.J. (2019). Impacts of strategic orientations on new product development and firm performances: Insights from Saudi industrial firms. European Journal of Innovation Management, 22(2), 257–280.

- Alves, W., Ferreira, P., & Araújo, M. (2019). Mining co-operatives: A model to establish a network for sustainability. Journal of Co-Operative Organization and Management, 7(1), 51–63.

- Amin, M. (2015). The effect of entrepreneurship orientation and learning orientation on SMEs' performance: An SEM-PLS approach. J. for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 8(3), 215.

- Anderson, B.S., Kreiser, P.M., Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J.S., & Eshima, Y. (2015). Reconceptualising entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10), 1579–1596.

- Aris, N.A., Marzuki, M.M., Othman, R., Rahman, S.A., & Ismail, N.H. (2018). Designing indicators for co-operative sustainability: The Malaysian perspective. Social Responsibility Journal, 14(1), 226–248.

- Arshad, A.S., Rasli, A., Arshad, A.A., & Zain, Z.M. (2014). The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on business performance: A study of technology-based SMEs in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 130, 46–53.

- Arshad, D., Razalli, R., Julienti, L., Ahmad, H., & Mahmood, R. (2015). Exploring the incidence of strategic improvisation: Evidence from Malaysian government link corporations. Asian Social Science, 11(24), 105–112.

- Auh, S., & Menguc, B. (2005). Balancing exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of competitive intensity. Journal of Business Research, 58(12), 1652–1661.

- Azmah, O., Fatimah, K., Rohana, & Rosita, H. (2012). Factors influencing cooperative membership and share increment : An application of the logistic regression analysis in the Malaysian co-operatives. World Review of Business Research, 2(5), 24–35.

- Badiru, I., Yusuf, K., & Anozie, O. (2016). Adherence to co-operative principles among agricultural co-operatives in Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 20(1), 142.

- Bakar, H.A., Mahmood, R., & Ismail, N.N.H.N. (2015). Fostering small and medium enterprises through entrepreneurial orientation and strategic improvisation. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(4), 481–487.

- Baldacchino, P.J., Camilleri, C., Grima, S., & Bezzina, F.H. (2017). Assessing incentive and monitoring schemes in the corporate governance of maltese co-operatives. European Research Studies Journal, 20(3), 177–195.

- Beck, J.T., Chapman, K., & Palmatier, R.W. (2015). Understanding relationship marketing and loyalty program effectiveness in G...: FOM hochschule online-Literatursuche. Journal of International Marketing, 23(3), 1–21.

- Beliaeva, T., Shirokova, G., Wales, W., & Gafforova, E. (2018). Benefiting from economic crisis? Strategic orientation effects, trade-offs, and configurations with resource availability on SME performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(1), 165–194.

- Birchall, J. (2013). The potential of co-operatives during the current recession; theorising comparative advantage. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity, 2(1), 1–22.

- Birchall, J., & Ketilson, L.H. (2009). Resilience of the cooperative business model in times of crisis. In Johnston Brichall Lou Hammond Ketilson.

- Brettel, M., & Rottenberger, J.D. (2013). Examining the link between entrepreneurial orientation and learning processes in small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4), 471–490.

- Brockhaus, R.H. (1980). Risk taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Journal, 23(3), 509–520.

- Brosens, I.A., Puttemans, P., Campo, R., Gordts, S., & Gordts, S. (2007). Endometriomas-more careful examination in vivo and communication with the pathologist. Fertility and Sterility, 88(2), 534.

- Cabaleiro-Casal, M.J., Iglesias-Malvido, C., & Martínez-Fontaíña, R. (2019). Co-Op open membership: Economic and financial effects. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 90(4), 669–686.

- Cardoza, G., & Fornes, G. (2011). The Internationalisation of SMEs from China: The case of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(4), 737–759.

- Casal, M.J.C., Malvido, C.I., & Fontaíña, R.M. (2019). Democratic firms and economic success. The co-op model. REVESCO Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 132(132), 29–45.

- Chaddad, F.R., & Cook, M.L. (2004). Understanding new co-operative models: An ownership-control rights typology. Review of Agricultural Economics, 26(3), 348–360.

- Chang, T.Z., & Chen, S.J. (1998). Market orientation, service quality and business profitability: A conceptual model and empirical evidence. Journal of Services Marketing, 12(4), 246–264.

- Chen, Y.C., Li, P.C., & Evans, K.R. (2012). Effects of interaction and entrepreneurial orientation on organisational performance: Insights into market driven and market driving. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(6), 1019–1034.

- Covin, J.G., & Slevin, D.P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior: A critique and extension. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(4), 7–25.

- Dunn, J.R. (1988). Journal of Cooperatives. In Journal of Agricultural Cooperation, 3(7).

- Dunn, J.R., Crooks, A.C., Frederick, D.A., Kennedy, T.L., & Wadsworth, J.J. (2002). Agricultural cooperatives in the 21st century. Commentary, May, 1–41.

- Engelen, A., Kube, H., Schmidt, S., & Flatten, T.C. (2014). Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 43(8), 1353–1369.

- Esteban-Salvador, L., Gargallo-Castel, A., & Pérez-Sanz, J. (2019). The presidency of the governing boards of co-operatives in Spain: A gendered approach. Journal of Co-Operative Organization and Management, 7(1), 34–41.

- Fellnhofer, K. (2019). Entrepreneurially oriented employees and firm performance: Mediating effects. Management Research Review, 42(1), 25–48.

- Figueras, M.T.B., & Garuz, J.T. (2019). Competitive strategies in agricultural cooperatives: The case of a rice cooperative, Catalonia, Spain. The International Journal of Business & Management, 7(6).

- Friesen, P., & Miller, D. (1982). Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3(1980), 1–25.

- Frösén, J., Luoma, J., Jaakkola, M., Tel, U.K., Tikkanen, H., Aspara, J., … & Laukkanen, M. (2016). What counts vs. What can be counted: The complex interplay of market orientation and marketing performance measurement in organisational configurations. Journal of Marketing, 1–60.

- G, D.K., & Manalel, J. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance : A critical examination. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 18(4), 21–28.

- Gaur, S.S., Vasudevan, H., & Gaur, A.S. (2011). Market orientation and manufacturing performance of Indian SMEs: Moderating role of firm resources and environmental factors. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7), 1172–1193.

- Goel, S. (2013). Relevance and potential of co-operative values and principles for family business research and practice. Journal of Co-Operative Organization and Management, 1(1), 41–46.

- Grashuis, J. (2018). The impact of brand equity on the financial performance of marketing co-operatives. Agribusiness, 35(2), 234–248.

- Gronum, S., Verreynne, M.L., & Kastelle, T. (2012). The role of networks in small and medium-sized enterprise innovation and firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(2), 257–282.

- Guzmán, C., Santos, F.J., & Barroso, M. (2019). Analysing the links between co-operative principles, entrepreneurial orientation and performance. Small Business Economics.

- Hadzrami, M., Rasit, H., & Ibrahim, M.A. (2017). Examining AIS software and co-operative performance in Malaysia. Indian-Pacific Journal of Accounting and Finance, 1(3), 4–12.

- Hakala, H. (2011). Strategic orientations in management literature: Three approaches to understanding the interaction between market, technology, entrepreneurial and learning orientations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(2), 199–217.

- Hammad Ahmad Khan, H., Yaacob, M.A., Abdullah, H., & Abu Bakar Ah, S.H. (2016). Factors affecting performance of co-operatives in Malaysia. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(5), 641–671.

- Hasbullah, N., Mahajar, A.J., & Salleh, M.I. (2014). The conceptual framework for predicting loyalty intention in the consumer cooperatives using modified theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(11), 209–214.

- Hilman, H., & Kaliappen, N. (2014). Market orientation practices and effects on organisational performance: Empirical insight from Malaysian hotel industry. SAGE Open, 4(4).

- Huang, C., Zazale, S., Othman, R., Aris, N., & Ariff, S.M. (2015). Influence of cooperative members' participation and gender on performance. Journal of Southeast Asian Research, 1–9.

- Hughes, P., Hodgkinson, I.R., Hughes, M., & Arshad, D. (2017). Explaining the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in emerging economies: The intermediate roles of absorptive capacity and improvisation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(4), 1025–1053.

- Hult, G.T.M., Hurley, R.F., & Knight, G.A. (2004). Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(5), 429–438.

- Hurley, R.F., Hult, G.T.M., Abrahamson, E., & Maxwell, S. (1998). Innovation, Learning: An organisational and empirical integration examination. Journal of Marketing, 62(3), 42–54.

- ICA. (2017). What is a co-operative? | ICA.

- International Co-operative Alliance. (2015). Statement on the co-operative identity definition of a co-operative.

- Ismail, M.D., Isa, A.M., & Ali, M.H. (2013). Insight into the relationship between entrepreneurship orientations and performance: The case of SME exporters in Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan, 38, 63–73.

- Kasim, A. (2016). A preliminary analysis on the connections between entrepreneurial strategic orientation on the growth of small and medium size hotels in peninsular malaysia and the moderating effect of firm strategy. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(7S), 485–491.

- Kerdpitak, C., & Boonrattanakittibhumi, C. (2020). Effect of strategic orientation and organisational culture on firm's performance. Role of organisational commitments. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 9(4), 70–82.

- Khalili, H., Nejadhussein, Syyedhamzeh, & Fazel, A. (2013). The influence of entrepreneurial orientation on innovative performance. Journal of Knowledge-Based Innovation in China, 5(3), 262–278.

- Kinyuira, D.K. (2019). Social performance rating in co-operatives. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Review, 3(2), 18–25.

- Kleanthous, A., Paton, R.A., & Wilson, F.M. (2019). Credit unions, co-operatives, sustainability and accountability in a time of change: A case study of credit unions in Cyprus. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(2), 309–323.

- Knight, G.A., & Cavusgil, S.T. (2004). Innovation, organisational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141.

- Kraus, S., Rigtering, J.P.C., Hughes, M., & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 161–182.

- Kreiser, P.M., Marino, L.D., & Weaver, K.M. (2002). Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: A multi-country analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 71–93.

- Laukkanen, T., Nagy, G., Hirvonen, S., Reijonen, H., & Pasanen, M. (2013). The effect of strategic orientations on business performance in SMEs: A multigroup analysis comparing Hungary and Finland. International Marketing Review, 30(6), 510–535.

- Lee, S.M., & Lim, S. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of service business. Service Business, 3(1), 1–13.

- Lin, C.H., Peng, C.H., & Kao, D.T. (2008). The innovativeness effect of market orientation and learning orientation on business performance. International Journal of Manpower, 29(8), 752–772.

- Lumpkin, G.T., & Dess, G.G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

- Malaysian Co-operative Statistics 2018. (2019). In Malaysia Co-operative Societies Commission (MCSC).

- Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J.T., & Özsomer, A. (2002). The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 18–32.

- Mayo, E. (2011). Co‐operative performance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 2(1), 158–164.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791.

- Musa, D., Ghani, A.A., & Ahmad, S. (2014). Linking entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: The examination toward performance of co-operatives firms in northern region of peninsular Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship, 4(2), 247–264.

- Musa, R., Hashim, N., Rashid, U.K., & Naseruddin, J. (2017). Accelerating startups: The role of government assistance programs and entrepreneurial orientation. International Journal of Economic Research, 14(15), 131–147.

- Nazri, M.A., Wahab, K.A., & Omar, N.A. (2015). The effect of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions on takaful agency's business performance in Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan, 45(2015), 83–94.

- Nilsson, J. (1996). The nature of co-operative values and principles: Transaction cost theoretical explanations. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 67(4), 633–653.

- Novkovic, S. (2005). Co-operative business: What is the role of co-operative principles and values? Sonja Novkovic ∗♦. International Cooperative Alliance Research Conference Cork, Ireland, 1–22.

- Novkovic, S. (2006). Co-operative Business: the role of co-operative principles and values. Journal of Co-Operative Studies, 39(1), 5–15.

- Novkovic, S. (2008). Defining the co-operative difference. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(6), 2168–2177.

- Novkovic, S., Prokopowicz, P., & Stocki, R. (2012). Staying true to co-operative identity: Diagnosing worker co-operatives for adherence to their values. In Advances in the Economic Analysis of Participatory and Labor-Managed Firms, 13, 23–50.

- Oczkowski, E., Krivokapic-Skoko, B., & Plummer, K. (2013). The meaning, importance and practice of the co-operative principles: Qualitative evidence from the Australian co-operative sector. Journal of Co-Operative Organization and Management, 1(2), 54–63.

- Onwe, C. (2020). Moderating Effect of dominant logic on the entrepreneurial orientation and microenterprises performance relationship in nigeria. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 26(1), 1–10.

- Othman, A., Mansor, N., & Kari, F. (2014). Assessing the performance of co-operatives in Malaysia: An analysis of co-operative groups using a data envelopment analysis approach. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(3), 484–505.

- Passey, A. (2005). Co-operative principles as 'action recipes': what does their articulation mean for co-operative futures ? Journal of Co-Operative Studies, 38(1), 28–41.

- Rasid, F. (2018). The affecting performance of co-operative in Malaysia. In SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G.T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787.

- Rezaei, J., & Ortt, R. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating role of functional performances. Management Research Review, 41(7), 878–900.

- Sabatini, F., Modena, F., & Tortia, E. (2014). Do co-operative enterprises create social trust? Small Business Economics, 42(3), 621–641.

- Schweiger, S.A., Stettler, T.R., Baldauf, A., & Zamudio, C. (2019). The complementarity of strategic orientations: A meta-analytic synthesis and theory extension. Strategic Management Journal, 40(11), 1822–1851.

- Seo, R. (2019). Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: insights from Korean ventures. European Journal of Innovation Management.

- Shakir, K.A., Ramli, A., Pulka, B.M., & Ghazali, F.H. (2020). The link between human capital and co-operatives performance. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(1), 1–11.

- Shamsuddin, Z. (2015). The efficacy impact of corporate governance compliance on the financial performance of cooperative. International Organization for Research and Development, c, 1–8.

- Shamsuddin, Z., Mahmood, S., Ghazali, P.L., Salleh, F., & Nawi, F.A.M. (2018). Indicators for cooperative performance measurement. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(12), 577–585.

- Somerville, P. (2007). Co-operative Identity. Journal of Co-Operative Studies, 5–17.

- Venkatraman, N. (1989). Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Management Science, 35(8), 942–962.

- Venkatraman, N., & Ramanujam, V. (1986). Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 801–814.

- Wales, W.J., Gupta, V.K., & Mousa, F.T. (2011). Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. International Small Business Journal, 31(4), 357–383.

- Wan, A.C. (2020). The contribution of SMEs to GDP increased by 38.3 per cent March 20.

- Wiklund, J., Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D.A. (2009). Building an integrative model of small business growth. Small Business Economics,32(4), 351–374.

- Yun, Y., Primiana, I., & Kaltum, U. (2019). Influence of supply chain management to performance through strategic cooperative operations in the field of food production cooperative in West Bandung regency. Proceedings of the first international conference on islamic development studies.

- Zahra, S.A., & Covin, J.G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 43–58.

- Zainol, F.A. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial orientation in Malay family firms in Malaysia. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 18(1), 103–123.

- Zakaria, N., Abdullah, N.A.C., & Yusoff, R. Z. (2017). Incorporating organisational innovation as a missing link in the examination of the eo-performance linkage. International Journal of Economic Research, 14(15), 49–60.

- Zeuli, K.A., & Cropp, R. (2004). Co-operatives: Principles and practices in the 21st century an ancient symbol of endurance and immortality. The two pines represent mutual cooperation-people helping people. In Socialeconomyaz.