Research Article: 2022 Vol: 28 Issue: 6

Social Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia Epistemological Positioning to Generate Open Systems

Abderrazak Belabes, King Abdulaziz University

Citation Information: Belabes, A.(2022). Social entrepreneurship in saudi arabia epistemological positioning to generate open systems. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28(6), 1-8.

Abstract

This article explores the epistemological assumptions of the social entrepreneurship literature in Saudi Arabia after studying it in detail in my teaching of a master course on social entrepreneurship at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah. Most publications are based on a positivist posture, while a minority adopts a constructivist posture. An epistemological posture that deals with social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia cannot fail to work both on the complexity of the phenomenon and the way to approach it. In this sense, social utility must not be limited to the object of study, it must extend to the epistemological posture through which this object is approached to avoid further cognitive bias which is learned attitudes that we are not always aware of. This awareness will not only allow a better approach to the subject but will also open the field of practice to the development of open systems and to get out of closed - entropic - and therefore self-destructive systems, as shown by research on the general systems theory which sheds light on the nature of complex systems, such as the case of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Complex Systems, Positivism, Constructivism, Social Entrepreneurship, Saudi Arabia.

JEL Classifications

D91, L31. M13, O35.

Introduction

Social entrepreneurship is a subject that I teach as part of the executive master's degree in economics and management of awqāf (endowment) and which gives me enormous pleasure which I share with the learners from all walks of life. Interest in social entrepreneurship has grown in the country under the impetus of Saudi Vision 2030, a transformative social and economic reform project that connects Saudi Arabia with the flows of genuine thoughts, fresh ideas, innovative projects, and best practices around the world. It will be a question of moving away from a closed system consisting in consuming knowledge and technology to a dynamic that generates knowledge and technology in accordance with the questions, needs and aspirations of the local society composed mainly of young people increasingly attracted to entrepreneurship.

The literature on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia, while still limited, is growing significantly. Although there is no agreed definition of social entrepreneurship, the general idea is that social entrepreneurship is about generating business opportunities that have a positive social impact. Most of the literature on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia published so far does not refer to the epistemological framework within which the research is conducted. The wide reader will probably notice that a significant part of the literature is tinged with positivism in the methodology used through the progressive construction of a common quantitative language ever more sophisticated giving the impression of an uncommon expertise. This form of ready-made trendy expression, borrowed in its essence from subjectivity, in a search for a supposed objectivity, does it not have repercussions on the objective of the creation of knowledge in terms of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia, the status of knowledge, its mode of elaboration and its validity criteria?

After exploring the conceptual foundations of the notion of entrepreneurship, it will put into perspective the two main epistemological orientations, i.e. positivism and constructivism, beyond what is usually taught in research methods course for beginners to distinguish between descriptive, analytical, statistical and comparative method. Unfortunately, most of those who obtain a PhD today believe that what they have learned in the research methods course constitutes the essence of methodology in its noble sense which explores how knowledge is constructed. Positivism postulates the existence of an objective world that can be described and represented in a direct way. In constructivism, knowledge is evaluated by the researcher's experience; his representation of what he is studying constructs this knowledge. In this epistemological position, reality does not exist independently of the researcher. For each of these postures, we will question their principles of justification and their conditions of methodological application in the context of exploring the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Finally, the study will shed light on the effects of the awareness of the epistemological position on the level of reading, conceptualizing, and writing on the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia.

Conceptual Foundations of the Notion of Social Entrepreneurship

This section addresses the premises of the notion of social entrepreneurship to answer the research question and shed light on the problem of the epistemological positioning of the research. The notion of entrepreneurship refers to the fact of starting an activity that is initiated by a person. More concretely, entrepreneurship refers to the fact of creating and developing an enterprise and giving life to a project.

Early Modern Works on Entrepreneurship

Early modern works on entrepreneurship deal with the development of big enterprises in the United States (Schumpeter, 1942; 1949). The reflection then extended to small enterprises (Churchill, 1955; Cooper, 1964; Steinmetz, 1969). This work gradually made it possible to understand that the techniques developed to support the development of big enterprises could not be applied to small enterprises. Birch (1979) research on the key importance of small enterprises in job creation seems to have kicked off the acceleration of research on the specific behavior of this type of enterprises and inaugurated a new field of research. Advances in research have shown that in the United States small enterprises create more jobs, although the difference is much smaller than what is suggested by Birch’s methods (Neumark et al., 2011). In contrast, for the European Union, smaller enterprises contribute on a larger scale towards job creation than larger enterprises do (Wit & Kok, 2014). This confirms the findings of an earlier OECD (1997) study showing that Small and medium-sized enterprises account for 60 to 70 per cent of jobs in most OECD countries, with a particularly large share in Italy and Japan, and a relatively smaller share in the United States.

The interest of this research development is to go beyond the generalization stage to distinguish between small and medium-sized and big enterprises and to discern different types of small and medium-sized enterprises not only by industry but also by structure and type of organization. It appears that it is only a small proportion of medium and small enterprises that create many jobs. It also transpires using field data that some of these small and medium-sized enterprises play a unifying role to stimulate social capital and thus support the dynamics of a local milieu particularly conducive to the entrepreneurial spirit.

The Emergence of Social Entrepreneurship

Other small and medium-sized enterprises act in a more locally rooted way by creating viable solutions to re-balancing economic, social, and environmental objectives. This type of initiative is now commonly referred to as social entrepreneurship which is an emerging phenomenon and a relatively recent notion whose contours do not appear to be predefined. In North America and Europe, the phenomenon emerged in the context of the economic crisis of the late 1970s in response to the limitations of traditional social and employment policies designed to combat poverty, exclusion and marginalization and the growing concern about competitiveness where innovation and entrepreneurship are emerging as structural determinants.

Although social entrepreneurs are becoming increasingly important in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, support structures remain largely in the minority. The main challenge remains access to resources, mainly financial, to enable the deployment of accelerator schemes for social innovation that provide social entrepreneurs with the means to achieve their ambitions. Innovation in the social entrepreneurship sector is not only characterized by the solution developed (product or service) to respond to the issue addressed, but also in the development of a business model that manages to reconcile economic sustainability and positive social impact.

Generating a positive impact is gradually becoming an obligatory variable in the social entrepreneurship equation. Social entrepreneurs have a responsibility to see the world in a creative, intelligent, and respectful way of the worlds (plants, animals, things) that surround us to propose innovative solutions to pressing economic, social, environmental, and ethical issues. The entrepreneur no longer seeks only to minimize his negative impact. He now wishes to reverse the trend to maximize his positive impact, and ultimately create value, which is social and economic.

The term social entrepreneurship has become part of national and international public policy discourses and orientations, and in some circles, it reflects high expectations of progress for society and quality of life. Depending on the meaning one gives to a phenomenon that appears to be ambivalent (Costales & Zeyen, 2022), the impact it is likely to have on the general conception of enterprise, or even society as a whole and the organization of life in the city, can be very different. Beyond the purely discursive aspect, which is receiving increasing attention from various actors and players nationally and internationally, is it about generating social value as a by-product of economic value, or economic value as a by-product of social value (Diochon & Anderson, 2011)? Despite the growing number of publications on social entrepreneurship, this issue has not received the attention it deserves.

The Research on Social Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia

In general, the research on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia draws on the existing literature on the subject, both conceptually and practically, with the ambition to go beyond the trendy triptych: economic growth, social progress, and preservation of the environment which are more of a major concern to rich countries. However, in view of the universal declaration of human rights, each human collective has the right to start from its own questioning that reflects its legitimate concerns, its deep aspirations, and its existential priorities.

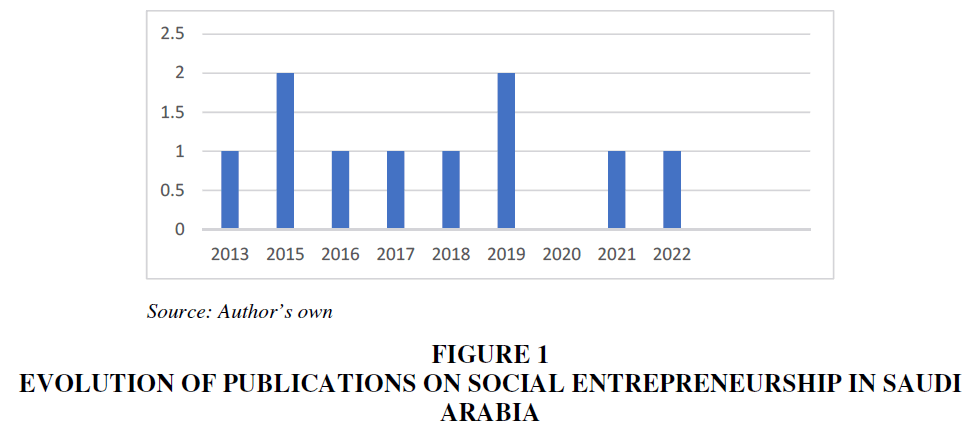

The literature on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is very recent, dating back less than a decade with varying frequency, as illustrated in Figure 1. This literature, which is still in its infancy and experimental validation, looks highly promising. Hence the need to refine epistemological positions to avoid the trap of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957), i.e. the unconscious tension of the researcher who cannot reconcile the visions underlying the idea being defended and the epistemological position consciously or unconsciously adopted.

The Epistemological Positioning of Research on Social Entrepreneurship

A review of the literature on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia reveals a clear tendency to approach research on this phenomenon with a positivist posture. Academic studies on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia, whether in management, finance, or charity work and awqāf are essentially based on a positivist framework. However, the conceptual anchoring of the notion of social entrepreneurship should direct the epistemological positioning towards a constructivist view of research.

Definition of Positivism and Constructivism

The first exploration in French literature shows that the term positivism was used by Saint-Simon (1760-1825) and popularized by Auguste Comte (1798-1857). According to the mainstream discourse on positivist doctrine, the positive (or scientific) spirit will, through the progress of the human mind, replace theological beliefs and metaphysical explanations. In this context, positivism is characterized by the abandonment of the why and the sole attachment to the how, to the search for the effective laws governing phenomena. The new edition of Saint- Simon's complete works (2013) sheds new light on the subject for anyone who wants to study positivism in any depth, to overcome the quarrels between those who would like to see Comte as a mere Saint-Simonian and those who reject this interpretation (Bourdeau, 2016).

A deeper exploration shows that the word positivism has a long history. It derives from the Latin ponere, which means 'to lay down', 'to deposit'. The past participle of ponere is positus. Since the 13th century, 'positive' has meant 'established'. In the 16th century, the term came to mean knowledge based on facts. Madame de Stael (1766-1817) was perhaps the first to refer explicitly to the idea of the philosophy of positive sciences and to relate it to social science. Henri de Saint-Simon, Comte's future mentor, had read her work. In a work of 1804, he took up his proposal to make the "science of social organization" a "positive science" based on Condorcet's theories of knowledge (Pickering, 2011).

Positivism claims to depict reality as it is, in an objective and universal manner. In this context, positivist epistemology aims to identify regularities in observed phenomena by pursuing a predictive purpose. It aims to provide a representation of reality as it is, through exploration and deductive testing. As a result, positivism claims to refer to a unique and immutable reality, existing independently of human action and accessible through scientific research.

In contrast, the constructivist posture considers the existence of a variety of socially constructed realities not governed by natural laws. The knowledge created in this framework is inseparable from lived experiences and will only be possible interpretations. The intention to know, language and representations will influence the way the situation is experienced and understood. This requires a critical reflection on how empirical material and data are socially constructed.

Impact of Epistemological Positioning on the Study of Social Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia

The choice of epistemological posture has a clear impact on the work of the researcher studying social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. It will condition the conception of social entrepreneurship and the perceived status of the researcher's subjectivity. The researcher who adopts a positivist stance will perceive his or her perceptual filters as cognitive obstacles to the quest for objectivity. They will seek to control them so that they have as little influence as possible on the results of the research. On the other hand, the person who adopts a constructivist posture, in his eminently subjective approach, will consider his perceptual filters as an integral part of the research.

Regarding the publications collected until now (Alzalabani et al., 2013; Nieva, 2015; Aloulou, 2016; Sulphey & Alkahtani, 2017; Alarifi & Alrubaishi, 2018; Alarifi et al., 2019; Hakami, 2021; Pérez-Nordtvedt & Fallatah, 2022), the positivist position is clearly predominant, except for one that is more constructivist (Alharthi, 2019). Most of these writings start from the posture that believes it can contemplate what is, facts as they are, without having previously explored the presuppositions that underline such an epistemological posture to stand out from what it quite simply assimilates to error, to lies, to falsehood, be it religion and metaphysics in early Auguste Comte days, or what was later called ideology (Schumpeter, 1949).

Any researcher who explores the presuppositions of the positivist posture, i.e. the conditions that make knowledge possible, will become aware of his claim to know what he is talking about and his claim to self-limitation of his own knowledge as a guarantee of authenticity. This will have all sorts of consequences for what social entrepreneurship is in Saudi Arabia and how it is studied. This awareness could lead to the concern to free oneself from the positivist epistemological posture and from its conditioning which are difficult to evacuate all at once. So, is it possible to move on, without seeing the real escape once again? And without either taking the facts for what they are not.

An epistemological posture worthy of the name that deals with social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia cannot fail to integrate the complexity of the phenomenon, i.e. break with all oppositions that are only justified by themselves. The wise researcher is the one who not only accepts being surprised, but who covets surprises to make them objects of research for which he can constantly revitalize himself off the beaten track.

Social utility, with its potential positive or negative effects, should not be confined to the object of study, i.e. social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. It should extend to the epistemological posture through which this object of study is approached. Social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is not only an object of study, it is an ongoing discovery of its object through the overcoming of the epistemological posture previously adopted, i.e. its continuous enrichment.

Conclusion

The highlighting of positivist epistemological positions which underlies many writings on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia confirms that positivism still has a virtual monopoly of the frame of thought of academic research with some variants which clarify or perfect it (Bouleau, 2020). This raises a paradox in the sense that the positivism that appeared more than two centuries ago does not respond to the social, ecological, ethical, and economic emergencies that social entrepreneurship strives to resolve. It is therefore important to understand not only the limits of positivism but also its genesis and its presuppositions insofar as it seeks neither ultimate ends nor first causes. This is all the more pertinent, given that religious sensitivity is often mentioned as one of the relevant factors that weigh the choice of the social entrepreneurship project in Saudi Arabia.

The constructivist position taken by some researchers to conceptualize the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is based on the idea that knowledge is a construct resulting from the interaction between the observer and the observed and not an exact reflection of the observed. There is not just one reality, there are many realities. This opens the field for consequential relativism-not the binary of positive/unrealistic, but the comparative of 'real for someone'.

What is important for future research on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia, beyond the constructivist positioning which must not succumb to the temptation of anti-positivism, is to privilege an approach of a knowledge based on what it imports, allows, or does not allow to consider. Knowledge should not be approached from the point of view of its claims to scientific validity regarding a specific principle, but from the point of view of the social utility and the problem to which it responds and the constraints that engage researchers to a particular path and not in another one regarding the conditions of possibility.

The challenge of highlighting the two epistemological positions regarding the literature on social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is to know whether we are moving towards a plural society or a market society. What makes Saudi Arabia resilient regarding its historical trajectory is the strength of the social bond that is nourished by common values. In this regard, social entrepreneurship is only truly social in the noble sense of the term if its impact is clearly in favor of the creation of social value through a process of inventing new solutions to social needs. Three criteria are then necessary for a process to be considered as a creation of social value:

• The first criterion is novelty by doing things differently, by proposing an alternative, or by creating a new combination of existing means that feed on local resources.

• The second criterion is the improvement of existing solutions.

• The third criterion is that the creation of social value (benefits for the population or society in general) has more favor than private value (personal return for the entrepreneur or investor).

In a society where the market sphere is almost exclusive, the satisfaction of people's needs necessarily implies that they have sufficient monetary income. The consequences of social inequalities are then considerably amplified. The commodification of life also profoundly changes the meaning and nature of relationships between people. The market is never a neutral tool for organizing society. Market choices not only reflect inequalities based on purchasing power, but they also contribute, in a way, to legitimizing them. Similarly, the extension of market norms modifies the behavior of individuals by crowding out practices based on empathy that encourages taking an altruistic action to help a person in need, sadaqah which constitutes a voluntary act of charity that is wide-reaching, and Iḥsān that involves achieving excellence in any action taken.

References

Alarifi, G., & Alrubaishi, D. (2018). The social entrepreneurship landscape in Saudi Arabia. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 24(4), 1-8.

Alarifi, G., Robson, P., & Kromidha, E. (2019). The manifestation of entrepreneurial orientation in the social entrepreneurship context. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 10(3), 307-327.

Alharthi, G. (2019). Social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: social entrepreneurs perception and social capital. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London.

Aloulou, W.J. (2016). The advent of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: Empirical evidence from selected social initiatives. In Incorporating Business Models and Strategies into Social Entrepreneurship.

Alzalabani, A., Modi Rajesh S., & Haque, M.N. (2013). Theoretical perspective of social entrepreneurship: A study of determinants of social entrepreneurship in the context of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 9(4), 571-581.

Birch, D. (1979). The Job Generation Process. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bouleau, N. (2020Introduction to the philosophy of science. Paris: Spartacus-IDH.

Bourdeau, M. (2016). News on the reports of Comte and Saint-Simon? European Journal of Social Sciences, 54(2), 277-288.

Churchill, B.C. (1955). Age and expectancy of business firms. Survey of Current Research, 35(12), 15-19.

Cooper, A.C. (1964). R&D is more efficient in small companies. Harvard Business Review, 42(3), 75-83.

Costales, E., & Zeyen, Anica. (2022). Social Entrepreneurship and Grand Challenges: Navigating Layers of Disruption from COVID-19 and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diochon, M., & Anderson, A.R. (2011). Ambivalence and ambiguity in social enterprise; narratives about values in reconciling purpose and practices. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7, 93-109.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hakami, Sami. (2021). The role of social entrepreneurship in community development. A case study of social entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Psychology and Education, 58(2), 154-161.

Neumark, D., Wall, B., & Zhang, J. (2011). Do small businesses create more jobs? New evidence for the United States from the national establishment time series. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 16-29.

Nieva, F.O. (2015). Social women entrepreneurship in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5(11), 1-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

OECD. (1997). Small Business, Job Creation and Growth: Facts, Obstacles and Best Practices. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pérez-N., & Fallatah, E. (2022). Social innovation in Saudi Arabia: The role of entrepreneurs’ spirituality, ego resilience and alertness. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(5), 1080-1121.

Pickering, M. (2011). Philosophical positivism: Auguste Comte. Interdisciplinary Journal of Legal Studies 67(2), 49-67.

Saint-Simon, H. (2013). Complete Works. Critical edition presented, established and annotated by juliette grange, pierre musso, philippe régnier and franck yonnet. Paris: PUF.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1949). Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial History. In Change and the Entrepreneur: Postulates and the Patterns for Entrepreneurial History, 131-142.

Steinmetz, L. (1969). Critical stages of small business growth. Business Horizon, 12(1), 29-37.

Sulphey, M.M., & Alkahtani, N. (2017). Economic security and sustainability through social entrepreneurship: The current Saudi Scenario. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 6(3), 479-490.

Wit, Gerrit de Wit & Kok, Jan de. (2014). Do small businesses create more jobs? New evidence for Europe. Small Business Economics, 42, 283-295.

Received: 03-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12560; Editor assigned: 04-Oct-2022, PreQC No. AEJ-22-12560(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Oct-2022, QC No. AEJ-22-12560; Revised: 22-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12560(R); Published: 25-Oct- 2022