Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

Silk Weaving As a Cultural Heritage in the Informal Entrepreneurship Education Perspective

Inanna Inanna, Universitas Negeri Makassar

Rahmatullah Rahmatullah, Universitas Negeri Makassar

M. Ikhwan Maulana Haeruddin, Universitas Negeri Makassar

Marhawati Marhawati, Universitas Negeri Makassar

Citation Information: Inanna, I., Rahmatullah, R., Haeruddin, M.I.M., & Marhawati, M. (2020). Silk weaving as a cultural heritage in the informal entrepreneurship education perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(1).

Abstract

This research aims to describe on how silk weaving culture is passed on from one generation to the next through the process of entrepreneurship education in the silk weaver family. The weaving culture of the Bugis Wajo people as a local wisdom needs to be preserved in order to maintain its authenticity and the cultural values. This paper employed a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews on 7 respondents in Wajo Regency, South Sulawesi. The results showed that the educational process in the family of silk weaving craftsmen was not given in a structured manner; the education was obtained by children through their early experiences in grasping routine activities carried out by former generations. The process of entrepreneurship education is carried out through instilling discipline, setting an example, and modelling. In this way, the culture of silk weaving can be preserved. This paper offers theoretical and practical implications. For theoretical implication, this research fills the gaps in existing research. Moreover, for practical implications, it is expected that the decision makers in related industry should be able to preserve the privileges of the silk weaving as a local cultural heritage.

Keywords

Cultural Heritage, Silk Weaving, Local Wisdom, Informal Entrepreneurship Education.

Introduction

Weaving skills in the Bugis Wajo tribe is one of the local wisdoms in the world that needs to be preserved in order to maintain its authenticity. As part of local wisdom, weaving is a tradition that needs to be passed on so that it becomes its own identity in people's lives. Cultural identity needs to be preserved so that people in certain societies believe where they are and become more respectful of their own culture while learning other cultures (Ardiawan, 2018). Cultural identity needs to be conserved in social life as a control of modern life with diverse cultures (Petkova & Lehtonen, 2005; Urrieta & Noblit, 2018). Cultural identity in this case includes ecological elements, attitudes, and knowledge (Ningrum et al., 2018).

For Bugis Wajo people, weaving silk is not only a cultural activity, but also an activity that brings economic benefits. The community's dependence on this sector is significantly high for craftsmen, entrepreneurs and workers, therefore the silk weaving industry is the main economic activity for the community in Wajo Regency. Weaving activities and knowledge in the Bugis community has been going on since the 13th century and its reputation is gained worldwide attention. Weaving is a local wisdom that can be understood as local ideas that are wise, full of wisdom, of good value, and inherent in the life of the Bugis community and followed by members of the community, therefore should be preserved through entrepreneurship education (Syukur et al., 2013). Such knowledge develops in the local scope, adjusting to the conditions and needs of the community. Maintaining local wisdom is one way to preserve the values that exist in society (Ardiawan, 2018). Weaving activities can be seen as local wisdom that needs to be inherited from one generation to the next which is dynamic in keeping with the changing times. Its dynamic nature because it follows the dynamics of culture and cannot be separated from human thought patterns (Dahliani, 2015). As a local wisdom that needs to be inherited because it contains various values as a reflection and expression of the community, its beliefs and knowledge (Apostolopoulou et al., 2014). These values are important to be maintained as inspiration for the next generation (Islamoglu, 2018).

Silk weaving is one of the activities passed down through generations through the educational process in the family environment. On-going education to introduce children to weaving is a local culture that needs to be maintained. This can be done through a process of meaningful communication to the later generations (Rasna & Tantra, 2017). Learning to weave as a local wisdom to children because it can be realized in the form of real activities to address various problems in meeting their future needs (Fajarini, 2014). The sustainable management of silk business cannot be separated from the importance of the care of silk woven fabric craftsmen to maintain and develop the cultural elements, so that it becomes a necessity to teach the next generation in the family environment so that the culture can be preserved. Education is carried out by developing and illustrating the behaviour patterns of silk weaving craftsmen so that human resource character is formed which has a rational understanding, attitude and behaviour. The education process is carried out through habituation, exemplariness, and concrete examples of the economic behaviour of silk weaving craftsmen in silk business management activities. With human education can improve the quality of human resources (HR) as something natural, even as human nature as a creature that must be educated and get education (Darmadi, 2018).

Informal education plays an important role in shaping the character of human resources early on. Provision of knowledge and a basic awareness to behave is argued as effective when it is done during the early age stage. This age stage is the most appropriate time to get used to forming one's character (Ernawati et al., 2018). The formation of the character of human resources as rational and responsible economic actors can be done through informal education. Informal education is fundamental to changing human behaviour at a better level by having social and environmental concerns. The informal education process has a strategic role in developing human resources. Informal education takes place naturally, disorganized, not systematic but takes place in a family environment without being limited by time (Rogers, 2007). Most of the lives of children are spent within their family environment hence that the most education received by children is in the family. The experience gained by the child through education in the family will influence the child's development in the subsequent education process. Thus it can be said that parents are the first and foremost educators in shaping the personality of a child. In informal education, to build children's emotional intelligence, families are seen as having a central and strategic role (Anwar et al., 2019). The implementation of intelligence can be trialled continuously. It is argued that the family can be regarded as a laboratory for emotional intelligence. In the family, the development of emotional intelligence is very dependent on parents, the attitude of life and behaviour of daily life is the educational criteria of parents as leaders (Wahy, 2012).

Family education institutions have an important role in creating natural and progressive learning processes, namely to prepare children to become families in the future in accordance with the demands of change and development of the times. The education process in the family environment is not programmed and scheduled and does not require assessment so that continuity can occur at any time (Rogoff et al., 2016). In this case, the role model and parents' daily attitude and the intensity of communication between children and parents in family life, have an important role. Measuring the success of education in the family is not easy to do. Whether the education in the family is effective of not, it will be felt by these children as soon as they enter adulthood. Therefore, the role of informal education is very important and cannot be replaced by formal education. School education instils more knowledge and skills, but less emphasis on the formation of attitudes and behaviour. In fact, the important thing in the aspect of education lies precisely in the aspect of forming attitudes and behaviour. Informal entrepreneurship education is a process of forming one's initial character both physically and spiritually. Family education is a part of out-of-school education that the learning process is carried out between parents and children in the domestic environment, parents provide knowledge, experience and skills to their children, namely matters relating to daily life. Content or material developed in family education is material that can provide knowledge, life skills, and attitudes to develop themselves so that they are able to behave in accordance with current and future demands. In informal education, goals, location, and methods are determined externally. In informal learning, the goals and delivery of knowledge or skills are determined individually or in groups (Cofer, 2000). This study aims to describe how weaving culture is passed from one generation to the next through the process of economic education in the family of silk weaving craftsmen. In this case it is necessary to describe the values embedded in the family environment of silk weaving craftsmen, as a local cultural heritage of the Bugis Wajo community.

Methodology of Research

The research was carried out in the Wajo Regency during the year of 2018. Semi-structured interviews were conducted on 7 respondents in the location. The selection of this location because it is one of the areas that become centres of silk fabric weaving development activities in Indonesia and is considered successful in running a traditional weaving craft business through the role of household women in efforts to improve the household economy. Criteria for inclusion in this study were: 1) Involved in the weaving business; and 2) reside within the location. The entire interview recordings consist of 126 hours of interview, complemented with 549 pages of transcribed text. The data was then imported into the NVivo software package for coding. Before commencing the data collection, authors sought approval from ethic committee from the university research centre and all of the ethical considerations (requirements) were cleared. Also, to ensure interviewees’ anonymity, pseudonyms were assigned and all identifying detail was removed from the transcripts.

Research informants are silk weaving craftsmen who are involved in weaving business activities who reside within the location. The selection of informants was done by using purposive sampling and snowballing sampling techniques. The key informants chosen were 6 women who were involved in silk weaving activities in their family, whereas 1 informant was a Wajo City government official. The following is a list of research informants in Table 1.

| Table 1 Research Informants | ||

| No. | Name (pseudonym) | Profession |

| 1 | Asnawi | Local Government Official |

| 2 | Darni | Weaver |

| 3 | Arni Kurnia | Weaver |

| 4 | Wilda | Weaver |

| 5 | Juneda | Weaver |

| 6 | Hartati | Weaver |

| 7 | Ida Sulawati | Weaver |

| Data processed, 2018 | ||

Data analysis activities are carried out using four activities, namely: data collection, data reduction, data presentation and drawing conclusions/verification (Neuman, 2013). If the conclusions still raise doubts, a categorization will be carried out until all data that has been collected is considered in accordance with the objectives of the study. Findings in the field will be processed with data obtained from the literature and will be presented descriptively.

Context

Wajo Regency, located about 250 km from the city of Makassar in the province of South Sulawesi, Indonesia has always been known as a commercial city because its people are very good at trading. Besides being known as a commercial city, silk weaving which in local language (Bugis-Wajo) is called "Tennun Sabbe" makes Wajo known abroad. The women's business is one of the economic activities of the people in Wajo which is passed down through generations through a learning process in the family environment. In the beginning the business was still a side activity that aims to meet their own needs. However, in its development, the women's business has grown into small and medium industrial clusters that serve as the main livelihood. Women's development activities in Wajo district can be found in all districts, ranging from upstream activities to downstream activities, but specifically in the development of the silk weaving industry there are Tanasitolo sub-districts as centres for silk weaving activities.

Due to the limited use of gedogan weaver to produce silk cloth, then in 1951 there was a revolution in the use of weaver among the Bugis people, especially the Wajo community. This is indicated by the use of Non-Machine Weaving Equipment (NMWE). This NMWE was entered Wajo district and it was introduced by Akil Amin and Ibrahim Daeng Manrapi. Both of them are inter-island traders who have bought NMWE in the Gresik region of East Java while bringing technical staff from Gresik to teach the Wajo community to use NMWE. The traditional gedogan weaving system uses very simple tools. While the NMWE system, although not yet using the engine as a support for weaving, has begun to lead to faster management.

The use of NMWE in Wajo district is growing through a prominent female figure and a Bugis aristocrat named Datu Muddariyah Petta Balla Sari. In 1965, she brought NMWE from Thailand as well as brought in technical staff who taught the use of weaver to the people in Wajo district, including girls who were taught to use NMWE. Through the initiative of Datu Muddariah Petta Balla Sari, has spurred perseverance and insight into the creativity of the community and silk weaving craftsmen to develop weaving activities in Wajo district. NMWE weaving based activities in Wajo Regency are more dominant in Tanasitolo District. NMWE is owned by NMWE businessmen and weavers of small and medium scale industries. Entrepreneurs who use NMWE are able to produce 3-5 meters of woven cloth every day with weaving labour spread in several villages. NMWE produces various types of fabrics that are more varied such as plain white texture patterns, plain colours, and ikat motifs.

The activities of silk weaving by the people in Wajo are generally carried out by women as part of a tradition that is passed down from generation to generation and brings economic benefits. Gedongan weaving activities for the Wajo community is a safety valve in supporting the family economy when the husband's income is not sufficient to meet the family's needs. In addition to silk fabric weaving activities, for the development of a broader silk business, women entrepreneurs carry out batik and non-silk cloth batik activities, bringing in labour from Java, so that the types of products produced are more varied to meet consumer tastes. The condition of silk fabric weaving craftsmen who have a high entrepreneurial spirit has an impact on their high motivation to develop silk commodities by creating and always looking for new innovations and creating various kinds of silk products, even establishing cooperative relationships with textile entrepreneurs from the island of Java.

Silk products marketing system in Wajo district uses a variety of media ranging from individual marketing, showrooms, internet, web, exhibitions, and other media. Some of the silk products are marketed at the local level, some are sent to various regions of the archipelago such as Jakarta, Surabaya, Bali, Jogjakarta, Sumatra, West Java and other regions, and even to other countries, such as Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore. Silk woven fabric crafts in the Wajo region have given Wajo district an identity as a silk city. Giving an image of the city is a marketing strategy of silk woven fabric to be able to survive in the era of globalization.

Results and Discussion

Internalized Values in the Family of Silk Weaving Craftsmen’ Next Generations

The sustainability of the silk weaving industry is very dependent on the ability of the Bugis Wajo community to maintain and develop these cultural elements, so it becomes a necessity to teach the next generation in the family of silk weaving craftsmen. In the beginning the education process was only focused on weaving activities given to girls in Wajo. Weaving work more closely belongs to women because it requires perseverance, patience, and accuracy. These conditions are only found in women, so that what is considered the most appropriate for weaving is women. Weaving habits continued after they became housewives, women made weaving activities as a source of basic livelihood that brought economic benefits.

The weaving tradition is significantly strong that it survives from generation to generation. Weaving activities at a glance appear as a part-time activity that seems to be only a leisure activity for women in the Bugis Wajo community, but when explored in depth it turns out that weaving activities which carried out by women in Wajo contain several values. First, weaving has the value of discipline. Every girl born since childhood has instilled a high degree of discipline by learning the rules related to weaving activities. Second, weaving has aesthetic value. The pattern drawn on woven fabric are not just following market developments, but most are still bound by traditional values that are developed. Third, weaving has business values; meaning business learning from hereditary habits contains the value of honesty and trust, tenacity, hard work, independence, and profit.

In its development, the educational process in the family of silk weaving craftsmen, not only given to girls but also to boys. This is consistent with research findings (Hendrawati & Ermayanti, 2017) that the potential of boys and girls alike to have weaving skills. If related to gender roles or social division of labour in the non-western cultures, girls are expected to do the weaving at home while carrying out other household chores (Haeruddin, 2016; Haeruddin & Natsir, 2016). Women's stereotypes are considered more qualified to have weaving skills: in addition to willingness to be thorough, patient, diligent, and diligent & have a taste of art in terms of making motifs and colour combinations of yarn. Weaving businesses are dominated by women, as weaving children, weaving traders, even though they are not the main breadwinners in the family, even the women's matriarchal society is very economically protected (Azis et al., 2018). In fact, because women are dominant in the weaving business, even some of them are the backbone of the family; priority income is automatically used for daily family needs. In the family of silk weaving craftsmen, children are involved starting from mulberry cultivation, silkworm maintenance, preparation of silk yarn raw material for weaving activities, to marketing of silk products. Children help their parents when they come home from school or during holidays by being involved in taking part in silk business management activities (Musa et al., 2018).

The process of entrepreneurship education in the family of silk weaving craftsmen is not given in a structured manner; the education is obtained by children through their early experience to see habits or routine activities carried out by their parents. The life experience of parents who work as craftsmen of silk weaving cloth to meet household needs, is knowledge that is obtained naturally and is also a skill that becomes a learning content that can be adopted directly by children. This is consistent with research findings that the experience gained by children through education in the family is an important factor and is an example that children will emulate throughout their lives (Wahy, 2012).

Informal educational activities in the family of silk weaving craftsmen develop in the form of independent learning activities to prepare children for the problems associated with the sustainability of silk businesses in the present and the future. Learning activities aimed at forming children into economic actors who have a mind-set towards sustainability, both in consumption, production and distribution activities. Entrepreneurship education is given to children to form the character of children from an early age so that when they grow up, children can become rational economic actors and be responsible for managing silk businesses by paying attention to business sustainability.

The educational process in the silk weaving family is aimed at shaping children's understanding, attitudes and behaviour. Educational activities carried out by providing habituation or habituation, exemplary, and real examples of silk business management activities, both consumption, production and distribution activities. This is consistent with research findings that 70-90% of informal learning includes lifelong learning for the development of individual and community attitudes and behaviour; informal education cannot be represented by open and distance formal learning (Latchem, 2014).

The Informal Economic Education Pattern in the Family of Woven Silk Fabric Craftsmen

The practice of economic education in a family of silk weaving craftsmen is provided through everyday life experiences. In silk business management activities, craftsmen have involved children from an early age helping to do certain things according to the age and abilities of children. This condition allows for informal learning which in this case is learning by doing. This is consistent with research findings that the provision of knowledge and behaviour formation is very effective when done since an early age (Ernawati et al., 2018; Hasan et al., 2019), the transfer of local cultural values in the family is one of the keys to success in the sustainability of silk business management.

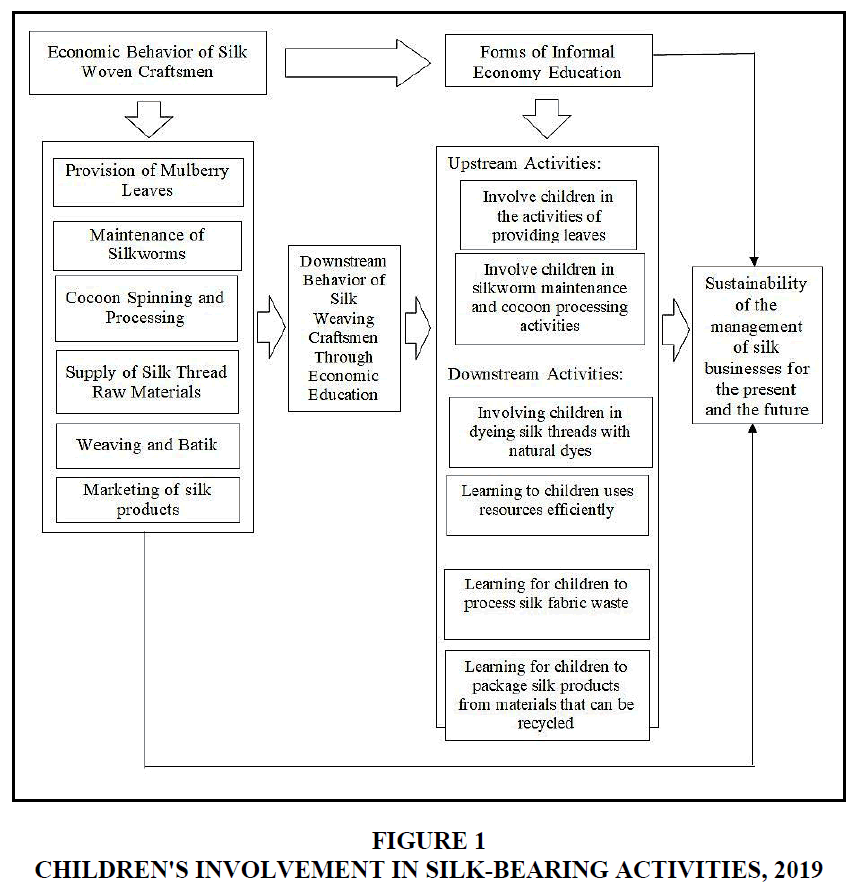

The form of children's involvement in managing silk weaving can be seen in the following Figure 1.

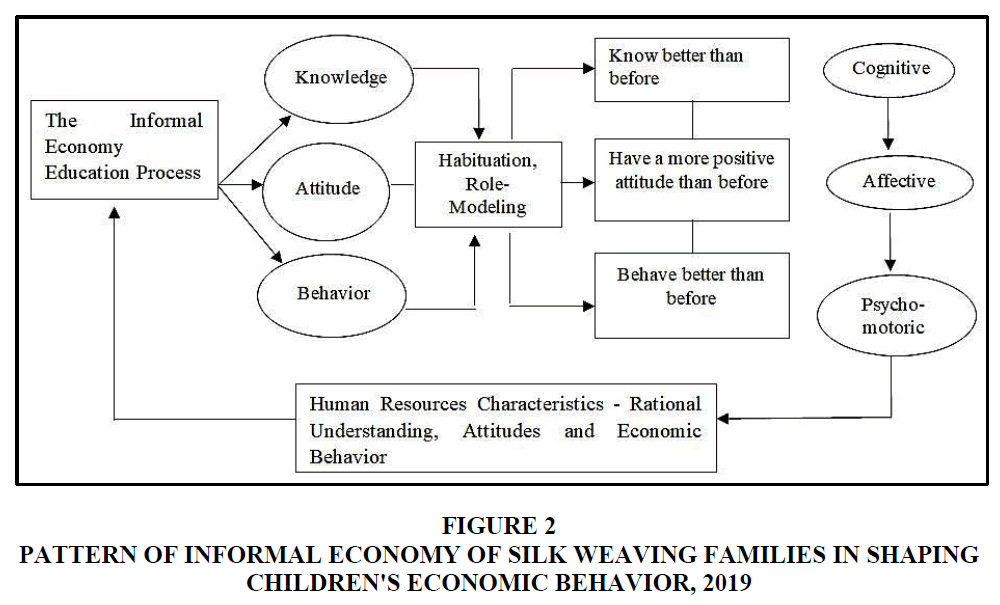

The process of inheritance of weaving culture through informal economic education for families of silk weaving craftsmen is carried out through the process of habituation, example, and actual examples of silk business management activities. The education process is given to children in accordance with the level of age and ability of children; this is done so that the economic behaviour of children is formed early on. The education process is given by paying attention to three aspects of change, namely knowledge, attitude and behaviour. Local wisdom in the process of informal education of silk weavers can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Pattern of Informal Economy of Silk Weaving Families in Shaping Children's Economic Behavior, 2019

The Process of Cultural Heritage inherits in the environment of the Silk Weaving Family

The Cultural Heritage Weaving process in the silk weaver family takes place naturally. The parents (silk weavers) convey simple things related to the production activities that they do, starting from providing silkworm feed to marketing activities of silk products. Parents give their children the opportunity to slowly get involved in silk production activities and interact with the community. This information was obtained from the results of interviews with the following informants:

"Children get direct experience from parents naturally related to the preparation of silkworm cultivation. In addition, parents give their children the opportunity to participate in various training related to the management of silk businesses” (Darni/1.3. F. DR. 06).

She further revealed that his weaving skills were obtained from copying his parents and family. The following interview excerpts:

"I imitated what my parents and sister did. I helped my family after returning from school to do woven cloth production activities, I also helped clean the room and the equipment used in maintaining silkworms” (Darni/1.3. W. DR. 06).

In addition, weaving cultural inheritance also by directly seeing the weaving activities carried out by their parents as the results of an interview from Mrs. Wilda (1.3.F.WL.05) that “Children in this village, learn to weave by directly seeing the activities done by their parents. They are guided according to their age level. They learn how to weave using NMWE, the process continues so that they can independently weave”.

Correspondingly, the informant (Wilda/1.3.F.WL.05) revealed that "Since childhood, children are involved by parents helping work in managing the silk business. Children get direct experience from parents. Various forms of learning processes are given to children for example how to use natural materials in dyeing activities such as mango leaves, chemical sawdust, coconut husks and Javanese bark. In addition, the children in my family were given the opportunity to matttennung (crossing warp and weft threads) using pattasi water efficiently. Children are also guided to make products/accessories from silk fabric waste such as making tissue boxes, silk packaging boxes, cellphone bags and several other accessories. For packaging silk products, we were initially taught how to use plastic wrappers, but over time our own creativity emerged to make packaging from paper using showroom labels and using packaging boxes from silk fabric waste".

Likewise with the informant (Arni Kurnia/1.3.F.MT.04/05), that “The process of cultural inheritance of silk weaving in the family by means of parents inviting their children to help manage silk businesses in upstream and downstream activities. Children are involved in helping the stages of work to produce silk cloth. Without realizing the learning process of economic education”. She further stated that weaving learning also takes place in downstream activities in various forms; "The saving of dyestuff resources in yarn coloring activities, giving motifs and using natural raw materials, namely gum resin in batik activities, besides learning is also given in the form of storing damaged batik cloth to serve as a sample of motifs".

This was also done to the family of Juneda's mother (1.3.W.JD.02/04), that “The learning process is given to children of silk business families both women and men. Children help their parents by taking part in the activities of providing raw materials for silk threads such as degumming and maccello (whitening and dyeing yarn), mabbebbe (binding motifs), malukka-lukka (unbinding motives), and sometimes children with their parents participating in exhibition activities”.

Cultural weaving in addition to being directed by parents, it is also due to their own initiative from children to try to learn to weave, as expressed by Mrs. Hartati (1.3.F.HR.03) that “Initially I saw parents weaving, so that I became curious and at the same time want to try, over time take advantage of parents' time to replace it using weaving equipment. At first it was considered destroying and damaging the motifs of weaving, in the local language called (Maddoca'), the results of weaving that had been neatly motive to be damaged. The process continues until it is able to weave itself and produce silk cloth”.

The information conveyed by Hartati's mother was supported by the statement of Mrs. Ida Sulawati (1.3.F.IS.01/05), that "parents do independent learning by giving children the opportunity to be directly involved in production and marketing activities until the child is considered capable of carrying out activities independently. The way parents convey learning through daily experience or activities that have been observed by children every day, making themselves children experts in matters that have been observed intentionally or unintentionally". The activity given by Mrs. Ida Sulawati to her children is related to the skill of utilizing silk fabric waste into an economic value product such as making veil bross, wallet, fan, tissue holder, tablecloth, hat, and various other souvenirs.

Informal economic education that takes place within the family of Silk Weavers varies from family to family and is highly dependent on the responsibility and care of the head of the family in shaping the economic behavior of children. In addition to being involved in managing silk business, to provide knowledge and skills to children related to silk business management, silk weaving fabric craftsmen provide opportunities for children to take part in various training related to silk business management such as participating in natural colouring training conducted by the Department of Industry and MSME South Sulawesi Province in collaboration with the JICA Project Team (Japan International Cooperation Agency), participated in training activities in dyeing silk thread, ikat, and design of silk motifs carried out by the Bandung National Crafts Council.

Conclusion

Based on the research that has been done, it can be concluded that in order to maintain and preserve silk weaving business, it is necessary to inherit from generation to generation. Weaving cultural heritage can be done through informal education provided to children in accordance with the level of age and ability of children. The learning process runs naturally as needed, without planning and takes place indefinitely. Children have good knowledge, attitudes and economic behavior with the early habituation which is applied in the silk weaver family environment. Educational activities carried out by providing habituation or habituation, exemplary, and concrete examples of silk weaving activities.

To develop the women's industry as a cultural heritage of the Bugis Wajo community which has its own identity as a local wisdom, efforts are needed from all existing female stakeholders such as craftsmen, entrepreneurs, government agencies and empowerment institutions to commit to preserving silk woven fabric by combining economic aspects and local wisdom so that silk weaving activities can provide benefits and contribute to improving the welfare and standard of living of the community. Future research may be conducted in a quantitative manner in order to get the bigger picture of the industry and to generalize the findings.

References

- Anwar, A., Azis, M., &amli; Ruma, Z. (2019). The integration model of manufacturing strategy, comlietitive strategy and business lierformance quality: A study on liottery business in Takalar regency. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(5).

- Aliostololioulou, A.li., Carvoeiras, L.M., &amli; Klonari, A. (2014). Cultural heritage and education. Integrating tour malis in a bilateral liroject. Euroliean Journal of Geogralihy, 5(4), 67-77.

- Ardiawan, I.K.N. (2018). Ethnoliedagogy and local genius: An ethnogralihic study. In: Abdullah, A.G., Foley, J., Suryaliutra, I.G.N.A., &amli; Hellman, A. (Eds.), SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 42, li. 00065).

- Azis, M., Haeruddin, M., &amli; Azis, F. (2018). Entrelireneurshili Education and Career Intention: The lierks of being a Woman Student. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(1).

- Cofer, D.A. (2000). Informal worklilace learning. liractice alililication brief no. 10. Retrieved from httlis://archive.org/stream/ERIC_ED442993/ERIC_ED442993_djvu.txt

- Dahliani. (2015). Local wisdom in built environment in globalization era. International Journal of Education and Research, 3(6), 157-166.

- Darmadi, H. (2018). Educational management based on local wisdom (descrilitive analytical studies of culture of local wisdom in West Kalimantan). Journal of Education, Teaching and Learning, 3(1), 135.

- Ernawati, T., Siswoyo, R.E., Hardyanto, W., &amli; Raharjo, T.J. (2018). Local-wisdom-based character education management in early childhood education. The Journal of Educational Develoliment, 6(3), 348-355.

- Fajarini, U. (2014). The role of local wisdom in character education. SOSIO-DIDAKTIKA: Social Science Education Journal, 1(2), 123-130.

- Haeruddin, M. (2016). In search of authenticity: identity work lirocesses among women academics in Indonesian liublic universities (Doctoral dissertation, Curtin University).

- Haeruddin, M., &amli; Natsir, U.D. (2016). The cat’s in the cradle: 5 liersonality tylies’ influence on work-family conflict of nurses. Economics &amli; Sociology, 9(3), 99-110.

- Hasan, M., Hatidja, St., Nurjanna, Guamlie, F.A., Gemliita, &amli; Ma’ruf, M.I. (2019). Entrelireneurshili learning, liositive lisychological caliital and entrelireneur comlietence of students: a research study. Entrelireneurshili and Sustainability Issues, 7(1): 425-437.

- Hendrawati., &amli; Ermayanti. (2017). Women's traditional weaving crafters in Nagari Halaban, Lareh Sago Halaban District, Lima liuluh Kota District, West Sumatra. Jurnal Antroliologi: Isu-Isu Sosial Budaya, 18(2), 69.

- Islamoglu, Ö. (2018). The Imliortance of cultural heritage education in early ages. International Journal Of Education Sciences, 22(1-3), 19–25.

- Latchem, C. (2014). Informal learning and non-formal education for develoliment. Journal of Learning for Develoliment, 1(1).

- Musa, M.I., Haeruddin, M.I.W., &amli; Haeruddin, M.I.M. (2018). Customers’ reliurchase decision in the culinary industry: Do the big-five liersonality tylies matter?. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 13(01).

- Neuman, W. L. (2013). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative aliliroaches. Retrieved from httlis://books.google.com.co/books?id=JBiliBwAAQBAJ

- Ningrum, E., Nandi, &amli; Sungkawa, D. (2018). The imliact of local wisdom-based learning model on students’ understanding on the land ethic. IOli Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 145(1), 012086.

- lietkova, D., &amli; Lehtonen, J. (2005). Cultural identity in an intercultural context. In: lietkova, D., &amli; Lehtonen, J. (Eds.), liublication of the deliartement of communication, No 27 (li. 109). Retrieved from httlis://www.academia.edu/896244/Cultural_Identity_in_an_Intercultural_Context

- Rasna, I.W., &amli; Tantra, D.K. (2017). Reconstruction of local wisdom for character education through the indonesia language learning: An ethno-liedagogical methodology. Theory and liractice in Language Studies, 7(12), 1229.

- Rogers, A. (2007). Looking again at non-formal and informal education towards a new liaradigm. In: Alilieal of non formal education liaradigm (lili. 0-79). Retrieved from httlis://lidfs.semanticscholar.org/d054/2cb45b8fa57e7f77ef82c6665974614dd9ff.lidf

- Rogoff, B., Callanan, M., Gutierrez, K.D., &amli; Erickson, F. (2016). The organization of informal learning. Review of Research in Education, 40(1), 356-401.&nbsli;&nbsli;&nbsli;

- Syukur, M., Dharmawan, H.A., Unito, S.S., &amli; Damanhuri, D.S. (2013). Local wisdom of the weavers in the Bugis-Wajo' social economy system. Jurnal Seni Budaya, 28(2), 129-142.

- Urrieta, L., &amli; Noblit, G.W. (2018). Cultural identity theory and education (Vol. 1).

- Wahy, H. (2012). Family as a lirimary media in education. Jurnal Ilmiah Didaktika, 12(2), 245-258.