Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 6

Self-control networks against the confinement caused by COVID-19

Javier Carreon Guillen, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Cruz Garcia Lirios, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Celia Yaneth Quiroz Campas, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Elias Alexander Vallejo Montoya, University of Sonora

Francisco Espinoza Morales, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Victor Hugo Merino Cordoba, Luis Amigo Catholic University

Carmen Ysabel Martinez de Merino, Autonomous University of Sinaloa

Luiz Vicente Ovalles Toledo, Guajira University

Clara Judith Brito Carrillo, Guajira University

Citation Information: Guillen, J.C., Lirios, C.G., Campas, C.Y.Q., Montoya, E.A.V., Morales, F.E., Cordoba, V.H.M., de Merino, C.Y.M., Toledo, L.V.O., & Carrillo, C.J.B. (2022). Self-Control Networks against the Confinement Caused By Covid-19. Journal of International Business Research, 21(6), 1-11.

Abstract

The pandemic has been studied from its effects on the confinement of people. The increase in cases of domestic and interpersonal violence has been associated with the anti-COVID-19 confinement policy. Migrants have been identified as those affected by immobility. The natives developed self-control to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus in the transition to teleworking. The objective of this study was to review the evidence of self-control and its dimensions reported in the literature during the period since the pandemic. A documentary, cross-sectional and exploratory study was carried out with a selection of findings published in sources indexed to international repositories. The results show that three dimensions prevail: self-management, self-regulation and self-efficacy that distinguish. In relation to the theoretical, conceptual and empirical frameworks, lines of research are recommended.

Keywords

COVID-19, Network, Self-Control, Self-Efficacy, Self-Management, Self- Regulation.

Introduction

Until May 2022, the pandemic has been identified in its final phase. It then means that infections, illnesses and deaths have been reduced to risk management (Guillen et al., 2021). Within the effects that the health crisis caused in the confinement and distancing of people, violence in the home or residence has rebounded. Reports of assault on a spouse, as well as domestic violence distinguish the period.

In this way, the objective of the present work was to establish the networks of findings around interpersonal violence derived from the pandemic. From a review of theories, models and categories, the axes of debate were established to model the relationships between the prevailing categories. This paper is to establish an ideology that disseminates the differences between cultures, identities and genders rather than their similarities. For this purpose, we worked with the assumption that the theoretical and conceptual frameworks of multiculturalism, identity and masculinity would underline the reductionism of migratory flows, gender identities and even masculinity to its minimum expression by confining it to exclusive attributes. In this way, the ideology becomes evident when analyzing the differences and similarities between multiculturalism with respect to interculturalism, masculinity before other feminine, lesbian, gay or transsexual identities, as well as youth in relation to other generations.

Are there significant differences between the structure of findings related to the impact of the pandemic on interpersonal relationships with respect to the observations and analysis of this work?

The premises that guide this work suggest that the pandemic generated greater interaction by forcing people to confine themselves (Garcia Lirios, 2015). In this sense, domestic or interpersonal violence increased while the health and economic crisis intensified3. In this way, the relationships between confined people escalated towards an asymmetry of opinions, resources and self-control capacities4. The most informed people generated a contingency plan that they modified based on the news update. In contrast, those who suffered the ravages of the pandemic limited their information to general issues without addressing the strategies of coexistence in overcrowding (Garcia Lirios, 2018). Very soon the differences between the confined people translated into systematic aggression and violence (Aguayo et al., 2020). Those who decided to face the situation learned strategies and obtained resources to endure the confinement, but those who were impacted by the crisis increased their emotions, channeling them to break with the people in confinement (Miranda et al., 2018). As the violence escalated from the attribution of responsibility to the authorities towards verbal or physical aggression with fellow inmates, a scenario of risk propensity emerged that explained the escalation of infections, illnesses and deaths associated with violence and COVID-19.

Self-Control Theory

Multiculturalist policies seek the inclusion of migrant communities in relation to the native population where welfare is prevalent, although such management instruments favor the marginalization of migrant groups located in the periphery of cities (Lirios et al., 2021). In this way, multiculturalism is associated with the assimilation hypothesis in which a dominant culture is imposed on other peripheral cultures, a phenomenon known as coinage (Fuentes et al., 2016). In other words, migrant communities, as dominated cultures, can arrive at equity if they conform to the guidelines of the dominant culture in a short period of time to balance the powers that subdue it.

Process of reproduction of social domination is mediated by self-knowledge of the dominant culture, because if it can identify their needs and expectations, can target the requirements of its values and norms and customs (Ochoa et al., 2018). This is a selective process in which the values are concentrated in a valuation nucleus that consists of linguistic and discursive competence for local resources between migrants and native people (Garcia Lirios, 2021). Those who were trained from a multicultural perspective did not always reach the values required for diversity and in cases where self-learning prevailed, citizens were more aware of respect for cultural differences and similarities (Garcia Lirios et al., 2017). The theory of multiculturalism postulates that modern societies can only be developed with the help of cultures that are willing to assimilate a universal system, such as English and multimedia communication, in order to achieve a parity of their abilities, since that the opportunities are generated to the extent that the market offers the corresponding jobs to the fittest people and that they perform better in the event of unforeseen changes in the modes of citizenship and inclusive participatory lifestyles.

In contrast, interculturalism ensures that the accelerated development of the most competitive cultures is not enough, but it is also necessary that those cultures that do not share the values of recognition and individual success can contribute to the dynamics of society and to the development of their systems economic, labor and educational (Lirios, 2021). In cultures, dialogue prevails over their values, and this is understood as a system of parity of forces, prevention of disagreements and overcoming conflicts between the parties that are not necessarily opposed, but rather ignorant of their common objectives.

The difference between multiculturalism and interculturalism lies in the degree of commitment, dialogue and concentration not only of the principles of life, but also of an approach to social co-responsibility, citizen cohesion and national identity (Garcia, 2019). In this way, the attachment to the place, the sense of belonging and community, as well as the attachment to a stage is fundamental to observe interculturalism while multiculturalism is often observed by tolerance rather than the acceptance of difference and coexistence.

That is to say that while the dialogue of differences, proclaimed by interculturalism, generates tolerance and not this debate, multiculturalism lacks self-criticism because it establishes as a guiding axis the values and norms of a dominant culture without considering the capacities of other dominated cultures (Molina, 2020). It is true that multiculturalism expects the other peripheral cultures to reach the development of nuclear culture, but it avoids the possibility that the dominant culture questions itself about the essence of its principles and based on it renounces its privileges, leaving a more equitable scenario regarding the management and administration of funds and resources (Lirios et al., 2019). Essences, interculturalism and multiculturalism underline the importance of differences between groups that generate the sense of belonging to a group and the comparison with their group of belonging with respect to a reference group.

Self-Control Studies

Studies of groups with gender identity and immigration status have shown differences that determine the quality of life and subjective well-being, but they have avoided the analysis and discussion of the ideological systems behind each category (Carrilo et al., 2018). The axes of ideological discussion were established from theoretical and conceptual frameworks related to multiculturalism, identity and masculinity (Garcia Lirios, 2019). A youth identity is “the appropriation of who one is from identifications and differentiations. In that sense, it involves a double look of the group and the other groups with which it interacts19. Or, from an intergenerational conflict with respect to adult generations (Sánchez et al., 2019). It is a selfrecognition with respect to other peer groups or different generations. In this way, differentiation and similarity between groups constitutes a first approach to youth identities that, due to their degree of claim and appropriation, generate rejection rather than the acceptance of other peer groups or different generations (Lirios et al., 2013). The youth identity is rather "the ability to be recognized and feel useful socially" (Aguiano-Salazar et al., 2018). Since it not only distinguishes it from adulthood, but also links the category with Human Development and its dimensions of income and poverty. It indicates a degradation of society in general and inherent to the youth sector (Nava-Tapia et al., 2019). In this way, social vulnerability rather than marginalization is predominant in contexts where multiculturalism prevails (Garcia Lirios & Bustos-Aguayo, 2021). In other words, the inclusion policies based on the tolerance of a dominant culture with respect to migrant cultures, generate juvenile identities that are violated rather than marginal, since the first term refers to a latent exclusion and the second to a self exclusion would answer and counter- cultural, a choice of life and style of social participation in the face of the denial of the contribution of young people to the multicultural system.

The theory of youth identities, unlike multiculturalism and interculturalism, observes in the denial of opportunities and capacities the central problem of migrant youth (Garcia Lirios & Bustos-Aguayo, 2021). In an opposite sense, multiculturalism implies the inclusion of migrant youths provided that these groups have the skills and job training that the multicultural system requires to facilitate equity between cultures. In that same sense, interculturalism only refers to dialogue without considering the imaginary; symbols, meanings and meanings from which the migrant youth leave, and which may be opposed to the social representations of the youth born (Garcia Lirios et al., 2013). Indeed, migrant youths suffer a multidimensional exclusion that lies in their values and norms, their uses and customs opposed to those of the hegemonic culture, or their capabilities limited to the opportunities that youths despise.

In this context, migrant youths build an identity that may have gone against the dominant culture, but now their priority is rather in recognition of their traditions and sense of community (Lirios et al., 2021). It is a process in which migrant youths produce an identity adjusted to the ideal of masculinity that lies in the challenge, the control of emotions and the recognition of achievements (Sandoval-Vázquez et al., 2022). Associated with heterosexuality, control, power, domination, strength, success, rationality, self-confidence and security, masculinity has been defined as opposed to other gender identities as Female.

The gender ideology that highlights the attributes wielded to the male identity bypasses the contributions of other feminine, lesbian, gay, transgender and transgender (Lirios, 2020). In addition, it limits the analysis of such attributes as indicators of a single gender identity, an exclusivity that would only be in masculinity, thereby defining masculinity as a hegemonic and one-dimensional identity without deviations or pathologies that reduce its attributes and confine it to a common identity (Lirios, 2021). Therefore, the theory of masculinity is one that studies ideology; the influence and power behind the exclusive attributes of masculinity that cannot be observed in other identities and whose attributes cannot be analyzed in masculinity either. In other words, masculinity is the result of a process of evolution that other identities cannot reach and much less achieve with attributes other than those associated with masculinity (Lirios, 2022). It is a hegemonic ideology in which identities are reduced to a minimum, including masculinity by confining it to the attributes.

The categories of multiculturalism, identity, masculinity and youth to highlight an ideology that underlines the importance of decisions and actions aimed at risk rather than coresponsibility (Lirios, 2020). Thus, this essay highlights the importance of discussing the convergence of categories to study the differences between cultures, identities and genders (Lirios et al., 2021). Unlike the reviewed studies in which the boundaries of cultural, identity, youth or gender groups are observed, this article highlights the importance of observing concatenation between categories to observe the diffusion of an ideology that limits an ethic of care, dialogue and consultation between the parties to the conflict (Lirios et al., 2022). In other words, the legitimacy of a system of violence over the construction of public peace prevails (Lirios et al., 2021). In that sense, it is necessary to deepen the indicators that reduce gender identities, migratory and native flows, as well as generations to their minimum expression.

The relationship between masculinity and migration is a criticism of the dominant masculinity and the claim of the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and transvestite gender identities (Garcia Lirios, 2021). From this fact, the theory of masculinity is built in which the values of challenge are highlighted, decision making in contexts of uncertainty and risk behaviors as hallmarks of new masculinities and their coexistence with other gender identities (Garcia Lirios, 2021). The studies of migrant masculinities focused in principle on the analysis of gender attributes such as the personality of the leader to lead to the analysis of the classic social movements of resources and identities and the new social movements of gender. Studies of masculinity revealed the rationality bias attributed to men and women with a certain profile of deliberation, planning and systematization of information (Lirios, 2021). This contributed to the emergence of feminist studies from a critical posture of rational masculinity and emotional femininity.

Within the framework of multiculturalism and interculturalism, migrant youth identities with male orientation are the result of tolerance and inclusion policies that consist of the legitimacy of a dominant masculinity - athletic body, rational decision making and systematic action - with respect to other gender identities, mainly the feminine one, since dialogue and coresponsibility, intercultural values are associated to the feminine identity through the ethics of care (Lirios et al., 2016). The ethics of justice in which rationality, audacity and systematization are linked to masculine identity, supposes a multicultural vision in which migrant cultures conform to the values of the dominant culture (Lirios, 2021). The new masculine identities are the result of multicultural systems that move towards interculturalism in which governance would be its indicator par excellence (Sandoval-Vazquez et al., 2021). The new youth masculine identities reflect the transition towards more participatory, deliberative and consensual societies, although the objective of this essay is rather to demonstrate the limits of both multicultural and intercultural systems regarding the new masculine identities, since some They exacerbate their positions and others merge with other gender identities (Lirios, 2021). Therefore, the model for the study of migrant youth identities with masculinity characteristics would include trajectory hypotheses between the dependencies relationships of the categories used in the present work.

The axes of discussion of ideological problems are circumscribed to multiculturalism as a policy of exclusion of gender identities different from the masculine one which is associated to Human Development. Gender identities, masculinity among them, are reduced to their minimum expression from multicultural policies that seek the inclusion of cultures but ignore their contribution capacities from different routes to masculine (Lirios, 2021). It is necessary to deepen the differences and similarities between cultures, identities and generations, since it depends on establishing the real and symbolic hegemony of some so that based on this, inclusion policies focused on government strategies rather than the formation of values, beliefs, attitudes, intentions and behaviors linked to risk.

Method

Based on the theoretical and conceptual frameworks of multiculturalism, identity and masculinity, the categories were related to highlight the ideology in comment. In this sense, a documentary study was carried out with a selection of sources indexed to repositories in Latin America, during the period from 2019 to 2022, considering the ISSN and DOI register, as well as its link with the keywords-self-control Table 1.

| Table 1 Descriptive of the Sample | ||||

| Repository | Self-control | |||

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Academia | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Clase | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Copernicus | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Dimensions | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Ebsco | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Frontiers | 6 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | |

| Latindex | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Microsoft | 2 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Redalyc | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Scielo | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Scopus | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| WoS | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Zenodo | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Zotero | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Source: Elaborated with data study | ||||

The Delphi inventory was used, which records the qualifications of expert judges in selfcontrol. In the first phase, the respondents rated the relevance of the abstracts selected in the repositories. The second part consisted of comparing the grade point averages with the initial criteria (Rincón et al., 2022). The third phase consisted of endorsing or reconsidering the initial rating. In each phase, the judges explained their positions and criteria based on the theory, the studies and the self-control model.

Participants were contacted through institutional mail. They were informed about the objective and those responsible for the project. The anonymity and proper use of their data was guaranteed in writing, through a confidentiality agreement. The guidelines of the Helsinki protocol for human studies were followed (Lirios, 2021). The project was adjusted to the guidelines of the APA standards alluding to the participants.

The respondents rated the summaries, considering a scale of five options: 0="not at all in agreement" to 5="quite in agreement". The data was captured in excel and processed in JASP version 15. The coefficients of normal distribution, homoscedasticity, adequacy, sphericity, linearity, centrality, grouping and structuring were estimated. Values close to zero were interpreted as evidence of non-rejection of the null hypothesis.

Results

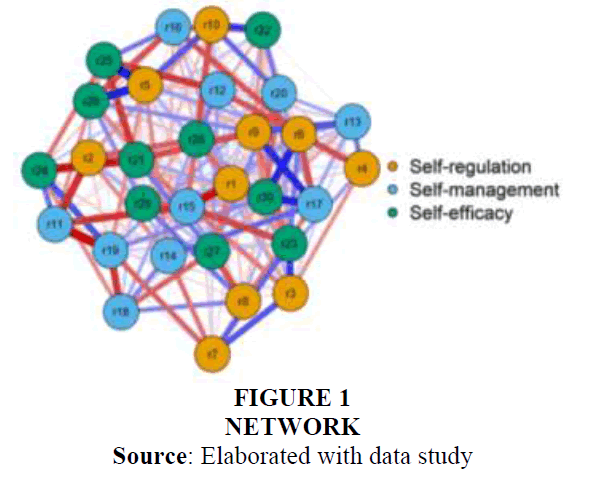

Figure 1 shows the relationships between the self-control categories. Self-regulation, selfmanagement and self-efficacy as central axes of the research agenda during the pandemic. The health and economic crisis, even though the figures on violence increased, did not lead to an individual crisis because the components of self-control were positively, negatively and significantly related. The literature consulted warns that the negative relationships between selfregulation and self-efficacy inhibited individualism in the pandemic. In addition, the positive relationships between self-management and self-regulation implied the orientation of individual projects towards social welfare.

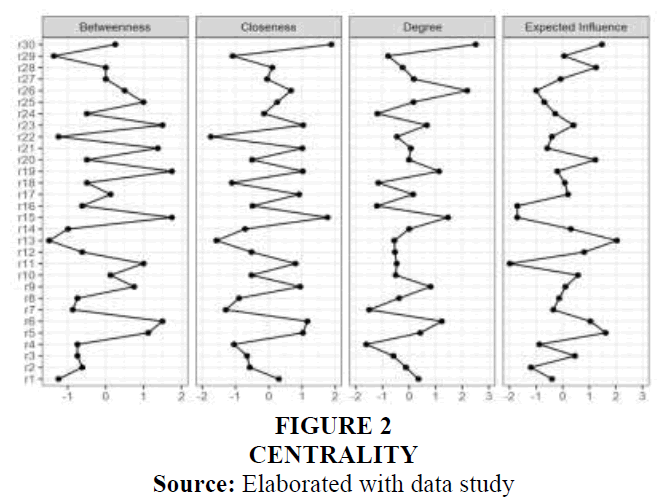

Figure 2 corroborates the structure of relationships between the findings. The values are close to zero indicating that the distance between the edges and the nodes is smaller, even when they are negative relationships, they suggest a grouping of the categories of self-regulation, selfefficacy and self-management around self-control. In other words, COVID-19 has led to a limited agglutination between the findings related to external factors such as violence and the nodes alluding to responses to the pandemic.

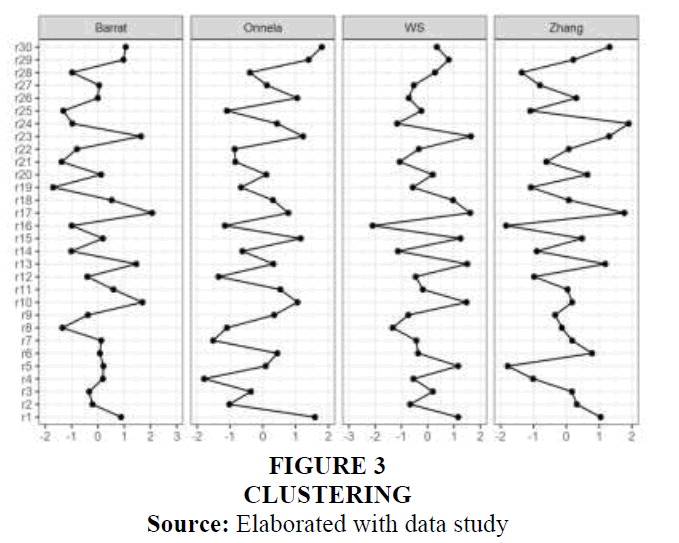

Figure 3 includes the grouping values between the edges and the nodes. The categories on which they are grouped suggest a self-control structure with dimensions related to selfmanagement, self-regulation and self-efficacy. That is, self-control, according to the literature consulted and the qualifications of the expert judges, is configured by features of information coding, data regulation and content dissemination that imply subjective well-being and limit interpersonal conflicts.

The analyzes of the findings reported in the literature suggest that self-control is a central axis in the research agenda when it comes to the effects of COVID-19 on the confinement of people. Self-control is configured in three dimensions related to self-management, self-regulation and self-efficacy. The tendency of people in confinement to seek information and process it to make decisions is reported in the literature as self-management. The preference of people in distancing to reduce or amplify information according to their beliefs, perceptions, motivations or attitudes is known as self-regulation. The ability of individuals to generate strategies to face the pandemic is referred to as self-efficacy. The three dimensions of self-management, selfregulation and self-efficacy make up a complex structure of self-control that allows them to face the health and economic crisis. The negative and positive relationships between the edges of the nodes suggest that the three dimensions of self-management, self-regulation and self-efficacy are oriented towards a balanced response to the pandemic.

Discussion

The contribution of the study to the state of the art lies in the establishment of three dimensions related to self-management, self-regulation and self-efficacy as responses to the health crisis. The review of findings around self-control suggests that the three dimensions are oriented towards a balanced structure. In relation to the theoretical, conceptual and empirical frameworks consulted, the structure of self-control is an improvised, but balanced response to the crisis of the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus and the COVID-19 disease. The confinement of people led to self-control in the search, processing and dissemination of information regarding the impact of the pandemic on personal health (Campas et al., 2020). Lines of research concerning the stigma of health professionals regarding risks of contagion, disease and death will explain the importance of self-control as a personal response to COVID-19.

Conclusion

The objective of the study lies in the establishment of a network of self-monitoring of personal health in the face of the pandemic. The results highlight the conformation of three dimensions related to self-management, self-regulation and self-efficacy. Self-control includes three dimensions that suggest a response to the health risks that the coronavirus posed. The findings reported in the literature reflect a general disposition of people in confinement that consists of the search, processing and dissemination of information about SARS CoV-2. In relation to risk communication policies that consist of reducing or amplifying the effects of the pandemic, this study suggests that the strategy feeds people's self-control.

References

Aguayo, J.M.B., Lirios, C.G., & Nájera, M.J. (2020). Security perception against COVID-19: Security perception against COVID-19. Academic Research Journal Without Borders: Division of Economic and Social Sciences, (34), 1-28.

Aguiano-Salazar, F., Aldana-Balderas, W., Valdés-Ambrosio, O., Delgado-Carrillo, M.D.L.Á., & Garcia Lirios, C. (2018). Exploratory factorial structure of an attitude scale towards groups close to HIV/AIDS carriers. Limit (Arica), 13(42), 61-74.

Campas, C.Y.Q., Lirios, C.G., Gonzalez, M.D.R.M., & Valencia, O.I.C. (2020). Reliability and validity of an instrument that measures entrepreneurship in merchants in central Mexico. Research & Development, 28(2), 6.

Carrilo, M.D.L.Á.D., Lirios, C.G., & Rubio, S.M. (2018). Specification of a model for the study of consensual migration. EQUITY. International Journal of Welfare Policy and Social Work, (9), 33-49.

Fuentes, J.A.A., Guillen, J.C., Lirios, C.G., Valdés, J.H., & Ferrusca, F.J.R. (2016). Governance of sociopolitical attitudes. New Era Rural Perspectives, (27), 107-148.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2015). Specification of a criminal behavior model. Psychological Research Act, 5 (2), 2028-2046.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2018). Specifying a model of representations of human capital in old age, youth and childhood.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2019). Dimensions of the theory of human development. Equity, (11), 27-54.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2021). Human, social and intellectual capital in the COVID-19 era: agenda setting, framing, plausibility and verifiability in repositories.

Garcia Lirios, C. (2021). Meta–analysis of perceived safety in public transport in the Covid–19 era. Mathematical Echo, 12(1), 107-116.

Garcia Lirios, C., & Bustos-Aguayo, J.M (2021). Design and evaluation of an instrument to measure internet use during the covid-19 era. CEA Magazine, 7 (14).

Garcia Lirios, C., Carreon Guillen, J., Hernandez Valdes, J., & Aguayo Jose, B.M. (2017). Sociopolitical reliability in coffee growers in Huitzilac, Morelos (central Mexico). Mediaciones Sociales, (16), 231-244.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Garcia Lirios, C., Carreón Guillen, J., Hernández Valdés, J., & Bustos Aguayo, J.M. (2013). Attitude of social workers towards carriers of the human immunodeficiency virus in community health centers.

Garcia, C. (2019). Organizational intelligence and wisdom: Knowledge networks around learning complexity. Psychogente, 22 (41), 1-28.

Garcia-Lirios, C. (2021). Construct validity of a scale to measure the job satisfaction of professors at public universities in central Mexico during COVID-19. Trilogy Science Technology Society, 13(25), 1-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guillen, J.C., Lirios, C.G., Mora, F.D.J.V., Bello, J.M., Rosales, R.S., & Alonso, L.D.Q. (2016). Reliability and validity of an instrument that measures seven dimensions of the perception of security in students of a public university. Thinking Psychology, 12(20), 65-76.

Guillen, J.C., Muñoz, E M., Morales, F.E., Nájera, M.J., Ruíz, G.B., Lirios, C.G., & de Nava-Tapia, S.L. (2021). Modeling of adherence to treatment of diseases acquired by asymmetries between work demands and self-control. Science and Health, 5(3), 13-26.

Lirios, C.G., Quiroz-Campas, C.Y., Carreon-Guillen, J., Espinoza-Morales, F., & Quezada, A.N. (2021). Confirmatory model of risk perception in the Covid-19 era. Journal of Marketing and Information Systems, 4(2), 97-106.

Lirios, C.G (2021). Human, Social, and Intellectual Capital in the COVID-19 Era: Establishing the Agenda. Framing, Plausibility, and Verifiability in the Repositories. Connection, (16), 133-150.

Lirios, C.G, Guillen, J.C, Valdés, J.H, Bustos, J.M, Campas, C.Y.Q, & Nájera, M.J. (2021). Transition towards the governance of the return to the face-to-face classroom in the face of anti-Covid-19 policies.

Lirios, C.G. (2020). Dimensional meta-analysis of trust: implications for the social communication of covid-19. Quotes, 6(1).

Lirios, C.G. (2020). Perception of public insecurity in the post COVID-19 era. Social Projection Magazine, 4(1), 45-53.

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Biosecurity and cybersecurity perceived before the Covid-19 in Mexico. Studies in Security and Defense, 16(31), 137-160.

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Deliberative partnership around abortion request in students from COVID-19. Social Work and Social Welfare, (3), 102-110.

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Knowledge Management, Intangible Assets And Intellectual Capitals in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Engineering, Mathematics and Information Sciences, 16(8).

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Occupational risk perceptions in the Post Covid-19 era. Know and Share Psychology.

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Vocational training in the post COVID-19 era. Education and Health Scientific Bulletin Institute of Health Sciences Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, 9(18), 42-47.

Lirios, C.G. (2021). Vocational training network: knowledge management, innovation and entrepreneurship. Papers: Specialized magazine of the Faculty of Educational Sciences, 13(26), 51-66.

Lirios, C.G. (2022). Modeling the management and incubation of talent. Interconnecting Knowledge, (13), 59-66.

Lirios, C.G., Guillen, J.C., Ornelas, R.M.R., Mojica, E.B., Sánchez, A.S., & Ruiz, G.B. (2019). Contrast of a knowledge management model in a public university in central Mexico. Journal of Management Sciences, (4), 105-127.

Lirios, C.G., Guillen, J.C., Valdés, J.H., Domínguez, G.A.L., Flores, M.D.L.M., & Aguayo, J.M.B (2013). Perceptual determinants of the intention to use the Internet for the development of human capital. In Business Forum. 18, (1), 95-117.

Lirios, C.G., Nájera, F.J., Aguayo, J.M.B., Nájera, M.J., & Nájera, F.R.J. (2022). Perceptions about Entrepreneurship in the COVID-19 Era. Critical Reason Magazine, (12), 6.

Lirios, C.G., Sánchez, J.A.G., Gracia, T.J.H., Guillen, J.C., & Morales, F.E. (2021). Contrast of a model of the determinants of the tourist stay in the Covid-19 era: implications for biosecurity. Tourism and Heritage, (16), 11-20.

Lirios, C.G., Valdés, J.H., & Gonzalez, M.M. (2021). Modeling the perception of security in the Covid-19 era. Academic Research Journal Division of Economic and Social Sciences, (36).

Lirios, CG, Guillen, JC, Valdés, JH, Aguayo, JMB, & Fuentes, JAA (2016). Specification of a sociopolitical hypermetropia model. Blue Moon, (42), 270-292.

Miranda, M.B., Balderas, W.I.A., & Lirios, C.G. (2018). Analysis of adherence expectations to the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) treatment in students of a Public University. Social Perspectives, 20(1), 53-70.

Molina, H.D. (2020). Peri-urban socio-environmental representations. Curly, 26(54), 5-12.

Nava-Tapia, S.L., Vilchis-Mora, F.J., Morales-Flores, M.L., Delgado-Carrillo, M.A., Olvera-López, Á.A., Mendoza-Alboreida, D., & Garcia-Lirios, C. (2019). Model specified from meanings around the climate and the institutional norm of workers of a health center in Mexico. Equity, (11), 11-25.

Ochoa, J.J.G., Ambrosio, O.V., & Lirios, C.G. (2018). Specification of a model for the study of the perception of risk events, community health, quality of life and subjective well-being. Academic Research Journal Without Borders: Division of Economic and Social Sciences, (27), 35-35.

Rincón, O.C., Gonzalez, M.D.R.M., Mojica, E.B., Guillen, J.C., Lirios, C.G., & Ferrusca, F.J.R. (2022). Governance strategy to agree on the expectations of students from a public university to return to classes interrupted by the pandemic. Magazine of the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences, 52(136), 319-338.

Sánchez, A., Bustos, J.M., Juárez, M., Fierro, E., & Garcia, C. (2018). Reliability and validity of a knowledge management scale in a public university in central Mexico. Hispano-American Notebooks, 17 (2), 1-12.

Sánchez, A., Valdés, O., Garcia, C., & Amemiya, M. (2019). Reliability and validity of an instrument that measures knowledge management. Space on White, 30(81), 9-22.

Sandoval-Vazquez, F.R., Aguayo, J.M.B., & Garcia-Lirios, C. (2021). Local development in the post covid-19 era. Huasteca Science Scientific Bulletin of the High School of Huejutla, 9(18), 17-22.

Sandoval-Vázquez, F., Nájera, M.J., Bustos-Aguayo, J., & Lirios, C.G. (2022). Confirmatory model of environmental expectations in the COVID-19 era. Academic Research Journal Division of Economic and Social Sciences, (37).

Received: 01-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12790; Editor assigned: 03-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. JIBR-22-12790(PQ); Reviewed: 17- Nov-2022, QC No. JIBR-22-12790; Revised: 24-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JIBR-22-12790(R); Published: 30-Nov-2022