Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 4

Saudi females??? attitudes and buying behavior towards advertising through sports

Mohamed AbdelKader Abdel Hamid, Dar Al Uloom University

Shaymaa Farid Fawzy, Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport College of Management & Technology

Citation Information: Hamid, M. A. K. A., & Fawzy, S. F. (2021). Saudi females’ attitudes and buying behavior towards advertising through sports. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 24(4), 1-16.

Abstract

Sports advertisement has a great impact on consumers’ decisions. Saudi Arabia as an example of a developing country is encouraging the Saudis females to be engaged in different sports fields according to vision 2030 action plan initiatives. The aim of the study is to investigate important factors that influence females’ attitudes towards sports advertisements, since females will contribute to the growth and progress of the country. The study adopted a quantitative approach through self-administered questionnaires that were distributed to Saudi females in fitness clubs/centers and sports events in Riyadh. Data was collected through two stages. In the first stage the researchers employed nonprobability sampling through convenient sampling but due to difficulty and the prolonged time for data collection a second stage of data collection was adopted through snowballing technique. The results showed that annoyance, falsity, good for the economy, hedonism, product information and materialism have no significant impact on females’ attitude towards advertising through sports and did not affect their buying behavior. Social image was the only factor that directly affected females’ attitudes towards advertising through sports. Females were more likely to be exposed to social influence such as: friends, colleagues, family and celebrities while they care more about their social image compared to other factors tested in the study. Based on the findings marketers will be able to design their marketing messages and increase the effectiveness of their advertising campaigns.

Keywords

Sports advertisement; Intention; Actual purchase; Social image; Vision 2030; Annoyance; Falsity; Good for the economy; Hedonism; Product information.

Introduction

Advertising is considered an important medium that provide consumers with updated information about the latest products or services. In the Arab society, females are important to marketer because of their purchasing power and shopping habits compared to those of their parents. Accordingly, it is essential for businesses to target female adults, as they are considered the growth segment in the market. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) there is a limited encouragement in sports, little development of sports and limited development of sports infrastructure except for Saudi’s soccer clubs. Moreover, there is limited participation of women in sports and sports events such as the Olympics until the appointment of Princess Reema Bint Bandar Al Saud, a prominent Saudi Princess, as head of a new Department for women’s affairs at the General Authority for Sports. This new development aims at encouraging women's participation in sports and develop women sports programs, as Saudi women participation in sports has been relatively rare because women were restricted in many fields, one of them is sports. Generally, the Saudi Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA, 2016) directed the General Authority for Sports to set up a Sports Development Fund. The Kingdom recently invested in sports to promote physical and social well-being and healthy lifestyle. In 2018, boxing championships, horse races, Gulf Cup and Formula One were among the other sports events hosted by KSA while also encouraging women’s football and allowing them to attend sports events as they were barred from participating in sports in public. Moreover, Saudi Arabia launches a soccer league for women as this is part of vision 2030 objectives targeting at bolstered sports activity in the country (CNN, 2020).

Vision 2030 goal is to increase the number of individuals exercising once a week from 13% of the population to 40% while encouraging females' society to participate in sports due to the increase in obesity rates and heart problems in the kingdom. According to Alharbi et al. (2017), the highest global prevalence of obesity, being overweight, is in the Kingdom. KSA government is encouraging all sports through the establishment of different sports bodies and organizing or participating in many global sports events. For example, the government established the Saudi Arabian Federation for Electronic & Intellectual Sports in 2017. The aim of it was to position the kingdom as a main e-sport hub in the Middle East and the world. Moreover, the Kingdom organized the First Formula E-Race in 2018. This event had a great global significance in motorsport. Also, the kingdom participated with its youth in the Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires and won three medals which is considered the greatest medal haul for Saudi Arabia. In addition, as part of the Saudi vision, the General Sports Authority organized a national competition for college students in 2019 to design and activate sports campaigns, participate in fitness-based movements and physical activities at least once a week to create healthy habits and changing Saudi culture to become more health conscious. Many global firms are taking advantage of this opportunity and started directing all their advertisements towards Saudi sports, health habits and Saudi females’ contributions in sports.

Literature Review

Nowadays, many international and global firms are investing in sports and are using sports as a vehicle to advertise their brands. They use sports as a medium to develop a unique image and to help in differentiating between their brands compared to competitors. The advertising industry worldwide is experiencing dramatic changes and has a great impact on the formation of consumers’ attitudes. Unlike any advertising media such as television, radio, magazines, social media, when people attend any of the sports events or have membership in fitness centers or clubs, they are presented to a wide range of advertisements. Females unlike males are usually less interested to watch sports channels, read sports magazines or specialized newspapers. For females to attend any of the sports events or to have membership in sports clubs and fitness centers means that companies will not waste their money or marketing efforts to advertise to a segment that they are not targeting. They will direct all their marketing efforts to the new targeted female segment which was previously culturally ignored in Saudi Arabia.

Today companies spend a lot of capital building brands through sports marketing. Consumers benefit from brands through minimizing search costs (Landes & Posner, 1987; Biswas, 1992) decreased perceived risk and increased the bond with companies. Generally advertising through sports can be through different tools such as in-stadium, sport facilities, sports clubs and sports teams. Other tools that marketers use for promoting products are the players' uniforms, equipment, stadium bench seats, corridors and walls. Using sports events in promoting products is increasing. Few researchers noted that people develop attitudes and form their behaviors based on advertisement through sports which consequently affect their purchasing decisions. Companies advertise through it to create awareness and to increase their sales regardless of understanding the psychological structures of what affected consumers to buy.

Generally, advertising through sports can be through different tools such as in-stadium/ sport facility signage. There have been previous studies examined the use of sport in advertising through in-stadium signage or signage located in any sport facility (Turley & Shannon, 2000; Pyun & Kim 2004; Pyun, 2006). In their studies, they investigated the effectiveness of advertising through sports events in terms of spectators recall or recognition based on attending or watching a sport event such as auto racing, football matches and camel racing. There are few studies which examined an individual’s attitude toward stadium signage, virtual advertising, banners or pop ups (Burns, 2003; Pyun & Kim, 2004). Another tool that marketers use for promoting products are the players’ uniforms, equipment, stadium bench seats, corridors and walls. There is a lack of research to measure attitudes towards advertising through sports throughout uniforms and players equipment. The previous literature review helped to identify the factors that affect consumers' attitude toward advertising in general (Pollay & Mittal, 1993; Ducoffe, 1996) or different mediums such as television (Alwitt & Prabhaker ,1992; Mittal, 1994) online (Burns, 2003), direct marketing (Korgaonkar et al., 1997) and outdoors (Donthu et al., 1993; Bhargava et al., 1994). Individuals perceive advertising differently and believing in advertising might differ from one person to the other. Pollay and Mittal (1993) differentiated between individuals’ personal uses and utilities of advertising from those that describe individuals’ perceptions of advertising from the societal and cultural perspectives. Their model of attitude toward advertising included three individuals’ personal uses factors (product information, social role, & hedonism/pleasure) and four societal and cultural factors (good for the economy, materialism, value corruption and falsity/no sense). Moreover, Korgaonkar et al., (2001) in their research studied Pollay and Mittal seven factors determinants of consumers’ attitude towards advertising which were as follows: product information, social role & image, hedonic/pleasure, value corruption, falsity/no sense, good for the economy & materialism. These factors were also common determinants in other studies such as in Tan & Chia (2007) and Petrovic et al., (2007) studies. The results reported by Pollay and Mittal and other researchers about attitude towards advertising generally provide the basis for applying them on sports advertising. A large segment in the community prefer a few sports in which they are forming communities and becoming fans of either the type of sports or the professional players. These communities are very loyal to those teams and very much committed. These segments are not studied intensively by marketers.

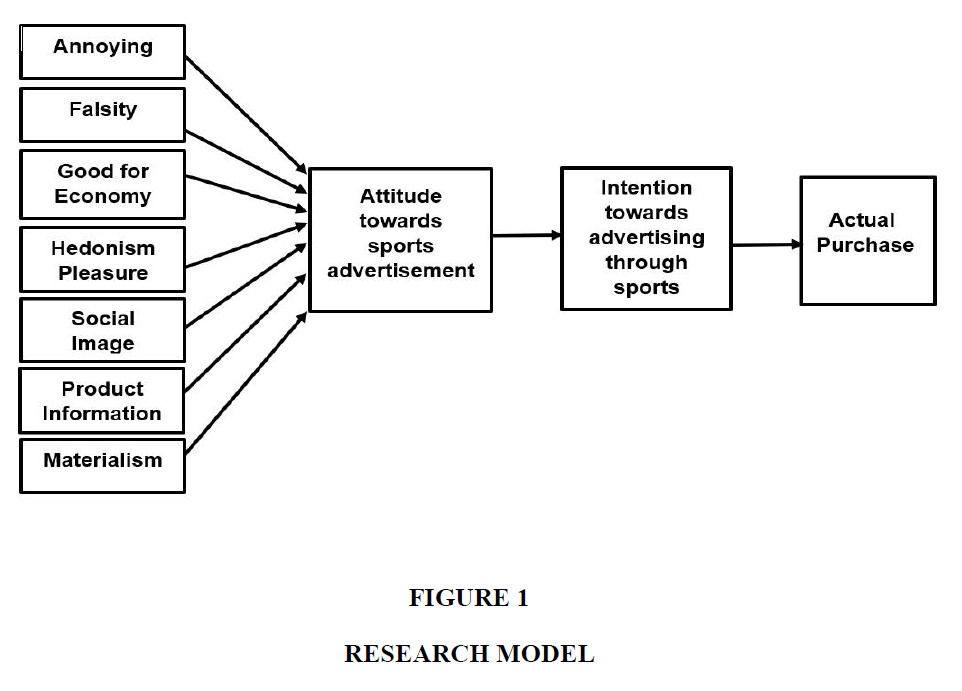

Sports is considered one of the crucial activities that is considered as an indicator of the growth and progress of countries (Keshkar et al., 2018). Females are newly targeted in the Saudi market as they are encouraged and allowed to practice all types of sports according to vision 2030 action plan initiatives. Accordingly, the main originality of the present paper is to fill the research gap in the literature and provide understanding of the effect of sports advertisement on females purchase decisions. Based on the literature there is a lack of research to investigate Saudis females’ attitudes towards advertising through sports and their buying behavior as they are newly and officially targeted today. The following is the proposed research model as shown in Figure 1.

Annoyance/Irritation

Nowadays people are exposed to a tremendous number of advertisements on daily basis especially the case of T.V commercials. Bauer and Greyser (1968) found that due to annoyance/ irritation because of advertisements, people tend to criticize advertising and have a negative influence on them (Alwitt & Prabhakar, 1994; Zhang, 2000; Pyun, 2006). Similarly, annoyance / irritation were investigated to examine their effect on people’s attitude towards advertising through sports and other medium (Zhang, 2000; Rettie et al. 2002; Wang et al, 2002; Wann et al., 2017; Byun & Kim, 2020). It was found that annoyance and irritation were mainly due to displaying the same advertisement repeatedly (Alwitt & Prabhaker, 1992). Moreover, it was found that there has been significant and negative correlation between annoyance/irritation and attitude towards advertising through sports. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H1: Annoyance/irritation of advertisement will have a negative impact on consumers’ attitude towards sports advertising.

Falsity/No sense

Bauer & Greyer (1968) explained the reason consumers perceived advertising as falsity/no sense was ’moral concern’ toward advertising such as the misleading advertising do to children and how it affects them negatively. Although Alwitt and Prabhaker (1992) noted that the misleading aspect of advertising did not contribute to the overall attitudes toward TV commercials, other studies assumed that falsity/no-sense negatively affect consumers’ attitude toward advertising through sport. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H2: A respondent’s belief(s) about advertising through sport representing ’falsity/no sense’ will negatively influence his/her attitude toward advertising through sport.

Good for Economy

Several studies conducted in the literature highlighted the importance of advertising on the economy. Bauer and Greysers (1968) indicated in their study that advertisement enhance consumers’ standard of living. According to Belch and Belch (2008) advertising help in employment, decrease the costs of production, acceptance of new technologies, creates competitions in which consumers takes advantage and benefit from it. In other studies advertising has an economic effect on consumers’ through providing them with knowledge and decrease searching time (Munusamy & Wong, 2007; Tan & Chia, 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Moreover, advertisement assist in information generation about products and services available in the market (Petrovici et al., 2007). By then it is considered good for the economy and consumers would have a positive attitude towards such advertisements. This is because advertisement through sports events depend on the product image, while branded products are easier to be promoted through sports events and minimize the cost of searching. According to the study carried out by Bauer & Greyser (1968), 70% of their respondents indicated the importance of advertisement in raising the standards of living of society and because of competition it encourages the production of quality products and helping customers to make better decisions based on their needs, wants and economic condition. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Positive projection in the context of good for the economy is positively affect consumers’ attitude towards advertising through sports.

Hedonic/Pleasure

Consumers perceive advertising from two different perspectives. Some consumers perceive it as fun and they get a lot of entertainment from it while others suggest that it is annoying. According to Petrovici et al., (2007) consumers may focus on the value they are looking for in the products advertisement. Hedonic and pleasure are considered one of the experiences consumers experience from advertisement. Consumers favor advertisements that provide pleasure and entertainment to them. According to Abd Aziz et al. (2008) advertisement will be considered valuable if they provide value to their audiences. Moreover, they stated that in order to attract customers towards the advertisement the message should reflect needs and wants of customers. According to Munusamy & Wong (2007) it is it is hypothesized that:

H4: Hedonic/ pleasure of an advertising message positively affect consumers attitude towards sports advertising.

Social Role/Image

Advertising is not only about selling a product or a service but on the other hand it can assist to sell consumers an image or lifestyle. Several studies indicated the role of advertising in building self-image and creating certain brand image (Friedmann & Zimner, 1988; Tharp & Scott, 1990; Richins, 1991; Burns, 2003). A brand can associate a certain prestige, social reactions accompanied with possession and /or actual use. Advertisers use sports to advertise through using attractive athletes to advertise products. Consumers perceive them as attractive and demonstrate a positive attitude toward advertising through sports. Advertising through sports develop consumers’ prestige, lifestyle and their own identity. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H5: Social role and image of advertisements affect consumers’ attitude towards advertising through sports.

Product Information

Advertising plays a vital role in delivering information about a company, a product or an idea. Based on the literature information acts as a valuable incentive for consumers to purchase (Schlosser et al., 1999; Haghirian & Madlberger, 2005; Wang & Sun et al., 2010). According to Popovic (2019), providing information to target customers enhances the knowledge of customers and help to educate them. Product information has a direct impact on consumers’ attitude towards product advertisement especially with new products. Consumers will judge the product based on the developed image they got from the product advertisement (Yee & Eze, 2012). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H6: Product information obtained through sports advertising messages affect consumer’s attitude towards sports advertising.

Materialism

Based on the literature it was noted that advertisement has a direct impact on consumers purchasing decisions. A study carried out by Pollay & Mittal (1993) indicated that 57.4% of their study sample agreed that most of the purchases done by the society are the outcome of advertisement and they highlighted the fact that because advertisement people are becoming more materialistic and purchasing items that they do not need. Moreover, Singh & Vij (2007) found that the majority of their sample indicated that advertisement took part to have a more materialistic society. The possession of goods is for the sake of showing off or to have a certain image and status in the society. Moreover, according to Popovic (2019) in his study on Montenegrin consumers, it was revealed that materialism, as one of the belief constructs, significantly influence consumers attitudes towards advertising through sports. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H7: Materialism affects individuals’ attitude towards sports advertisements

Consumers’ Attitude towards advertising

Attitude has been defined in the literature in several studies and in different aspects. Kotler (2000) generally defined attitude in terms of individual personal and emotional evaluation and feelings towards a certain object or idea. According to Mehta (2000) and Watkins et al. (2016) study, it was indicated that consumers’ attitude towards advertising is one of the crucial determinants of advertising effectiveness reflected on consumers’ intentions because consumer’s cognitive ability towards an ad are interpreted in consumers’ thought and emotions which according to Kotler (2000) this will influence their attitude generally and towards the advertisement specifically. There are several studies examining the impact of consumers attitude towards advertising and purchase intention through different advertising medium such as print, television, online and other medium (Fillis, 2014; Cocker et al., 2015; Cartwright et al., 2016; Justin & Shailja, 2018; Byun & Kim, 2020). Similarly, the results reported previously provide the basis for applying them on sports advertising. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H8: Attitude towards Advertisement positively affects Purchase Intention

Actual purchase

Organizations devote a lot of time and efforts to create advertisements that affect consumers’ positively through persuading them to purchase their products (Erdogan, 1999; Knoll & Matthes, 2017; Justin & Shailja, 2018). According to Byun & Kim (2020), people’s attitude towards advertisement has a direct impact on their intention to buy the advertised product and similarly this can also be applied on advertisement through sports and its impact on consumers’ buying decisions. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H9: Consumers Intention towards advertisement through sports affect their actual purchase

Methodology

A self-administered questionnaire was designed, in order to study the factors that affect females’ acceptance of sports advertisements and their impact on females purchase decisions. A pilot testing included 30 respondents has been carried out to ensure the reliability of the scale and to modify it according to comments, critiques and feedback. The questionnaire consisted of 36 items. Each item was measured using a 5- point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Table 1 shows the conceptual and operational definitions of variables. Demographic details such as age, gender, and education level were added.

| Table 1 Conceptual and Operational Definitions of the Variables Under Study | ||

| Variables | Conceptual Definition | Operational Definition |

| Product Information | ‘The ability of an advertisement to satisfy consumers by providing information about a product or service’ Ducoffe (1996) | Ducoffe, 1995 |

| Good for Economy | Belch and Belch (2008) suggest that the concept of ‘good for economy’ reflects the point of view that advertising speeds up the adoption of new goods and technologies by consumers’, fosters full employment, reduces the average costs of production, elevates producers about healthy competition, and increases the standard of living on average. | Pollay & Mittal, 1993 |

| Hedonic | Advertising can serve as a source of entertainment or pleasure (Alwitt & Prabhaker, 1992; Pollay & Mittal, 1993). | Pollay & Mittal, 1993 |

| Social role/Image | Munusamy and Wong (2007) reported that social integration role of advertising means that it presents lifestyle imagery, and its communication goals often indicate a brand image or personality, the representation of typical or idealized users, associated status or prestige, or social reactions to purchase, own and use (Jayasingh & Eze, 2012). | Pollay & Mittal, 1993 |

| Annoyance/Irritation | ‘The negative, anxious, and unsatisfactory feelings consumers experience when viewing diverse kinds of advertisement stimulations’ (Ducoffe, 1996). | Alwitt & Prabhakar, 1992 |

| Falsity/no sense | Advertising can be purposefully misleading, or more benignly, as not fully informative, trivial, silly, confusing (Pollay&Mittal, 1993). | Pollay & Mittal, 1993 |

| Materialism | Materialism is a set of belief structures that sees consumption as the route to most, if not all, satisfactions (Munusamy & Wong, 2007). | Wolin et al., 2005 |

| Attitude towards sports advertisement | Defined as a learned predisposition to react in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner to advertising (Lutz, 1985) Kotler (2000) further elaborates attitude as an individual personal evaluation, emotional feeling attached and action tendency toward some objects or ideas. | Wang & Sun, 2010 |

| Purchase Intention | According to Spears and Singh (2004), purchase intentions refer to the person's conscious plan in exerting an effort to purchase a brand. | Putrevu & Lord, 1994; Taylor & Hunter, 2002 |

| Actual purchase | The use of sports advertisement for making product purchases. | Martinez-Lopez et al., 2005; Patwardhan & Ramaprasad, 2005 |

The population of the study is Saudi females’ members in fitness clubs. According to Hair et al., (2016) the sample size could be calculated by multiplying number of questions in questionnaire by 5 to 10. The questionnaire has 36 items, then the total sample size if multiplied by 10 is 360. According to 2020 statistics the Kingdom population is 34,710,000. Where Saudi citizens represents 69% and 31% non-Saudi residents. The researcher distributed 460 questionnaires in 2 main ladies fitness clubs located in Riyadh, these clubs are characterized by having many branches since Riyadh is considered the capital and the largest city. Sampling frame could not be accessed from fitness clubs’ management because the privacy of members’ information is highly secured. The first stage the researcher started by employing non-probability sampling through convenient sample. Out of 460 questionnaires, 40 were incomplete and the researchers neglected them, while 274 were filled out by non-Saudi and were ignored from the sample. The researchers faced great difficulty from the fitness clubs to allow for data collection. The male researcher was not permitted to enter ladies’ fitness clubs and due to the conservative culture was not allowed to deal with females. The female researcher was in charge of data collection. Difficulty was a great challenge to researchers. Especially speaking to strangers is not accepted by the conservative cultures. Due to difficulty and the prolonged time for data collection based on the population of the study (Saudi female members of fitness club), a second stage of data collection was adopted through snowballing technique. This technique was used to recruit participants, where each participant was asked to nominate other person who would accept to participate in the study. Such technique was proposed by Neuman (2002) where it is adopted when the sample size is small or when there is a preference to select well-informed participants. In this stage, 146 Saudi respondents participated in survey completion after 6 months of data collection during different times during the day (morning, afternoon and early night).

Results and Discussion

The analysis was done using AMOS. Reliability Analysis (Cronbach Alpha) was used to measure the reliability of factors that affect consumers’ attitude towards sports advertisement. Table 2 shows different alpha values for the variables under the study. Where the overall reliability of the scale was above 0.9. According to Nunnally & Bernstein (1967) the scale is considered reliable when Cronbach Alpha coefficient is 0.45 or more. The research problem was addressed by investigating the factors that affecting Saudis’ female buying decision. Based on the sample drawn, more than half of the sample elements were between 20 and less than 30 years old (67% of the sample participants). Participants have been asked 5 screening questions about their sports lifestyle.

| Table 2 Convergent Validity, Discriminant Validity and Reliability | |||||||

| Latent variables & its Observed items | Items | SFL | C.R | SMC | CR | AVE | α |

| Annoyance & irritation | A4 | 0.425 | 3.618 | 0.181 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.663 |

| A2 | 0.672 | 3.923 | 0.451 | ||||

| A1 | 0.817 | Fixed | 0.667 | ||||

| Falsity/ No sense | C4 | 0.705 | 6.35 | 0.497 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.713 |

| C3 | 0.422 | 4.274 | 0.178 | ||||

| C2 | 0.83 | 6.436 | 0.688 | ||||

| C1 | 0.623 | Fixed | 0.389 | ||||

| Good for Economy | G2 | 0.792 | 2.502 | 0.627 | 0.7 | 0.54 | 0.503 |

| G1 | 0.667 | -0.733 | 0.218 | ||||

| G3 | -0.074 | Fixed | 0.005 | ||||

| Hedonism/Pleasure | H4 | 0.478 | 5.453 | 0.228 | 0.76 | 0.7 | 0.74 |

| H3 | 0.471 | 5.365 | 0.221 | ||||

| H2 | 0.898 | 7.758 | 0.806 | ||||

| H1 | 0.769 | Fixed | 0.592 | ||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.577 | Fixed | 0.333 | 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.748 |

| AT2 | 0.769 | 6.188 | 0.591 | ||||

| AT3 | -0.271 | -2.813 | 0.073 | ||||

| Social Image | S4 | 0.71 | Fixed | 0.444 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.865 |

| S3 | 0.783 | 8.305 | 0.587 | ||||

| S2 | 0.767 | 8.177 | 0.675 | ||||

| S1 | 0.736 | 7.898 | 0.542 | ||||

| Product Information | F3 | 0.821 | Fixed | 0.675 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 0.841 |

| F2 | 0.766 | 7.392 | 0.587 | ||||

| F1 | 0.666 | 7.027 | 0.444 | ||||

| Materialism | M3 | 0.594 | Fixed | 0.353 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.646 |

| M2 | 0.798 | 2.918 | 0.502 | ||||

| M1 | 0.365 | 3.019 | 0.133 | ||||

| Intention towards Advertising through Sports | IN1 | 0.657 | Fixed | 0.431 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.781 |

| IN2 | 0.656 | 6.747 | 0.43 | ||||

| IN3 | 0.672 | 6.008 | 0.328 | ||||

| IN4 | 0.675 | 6.905 | 0.455 | ||||

| IN5 | 0.711 | 7.2 | 0.505 | ||||

| IN6 | 0.46 | 4.935 | 0.211 | ||||

| Actual Purchase | AP1 | 0.597 | Fixed | 0.356 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.682 |

| AP2 | 0.794 | 6.272 | 0.524 | ||||

| AP3 | -0.286 | -2.997 | 0.082 | ||||

First was about their daily sports activities, 86% of participants were not exercising any of the sports activities as a daily lifestyle routine. In contrast, 65% of the participants have a fitness club membership but they are using it only 1-4 times a month. When asked about the type of sports they watch or practice: 61% Cardio & Aerobics, 16.4% watching football, and 13% not concerned to watch any sports games. 51% of the participants are athletes’ fans in different games but mainly football. Mobile Apps, Mobile social media, and TV were the many media tools used by participants to watch their favorite games (54.8%, 51.4%, and 41% respectively).

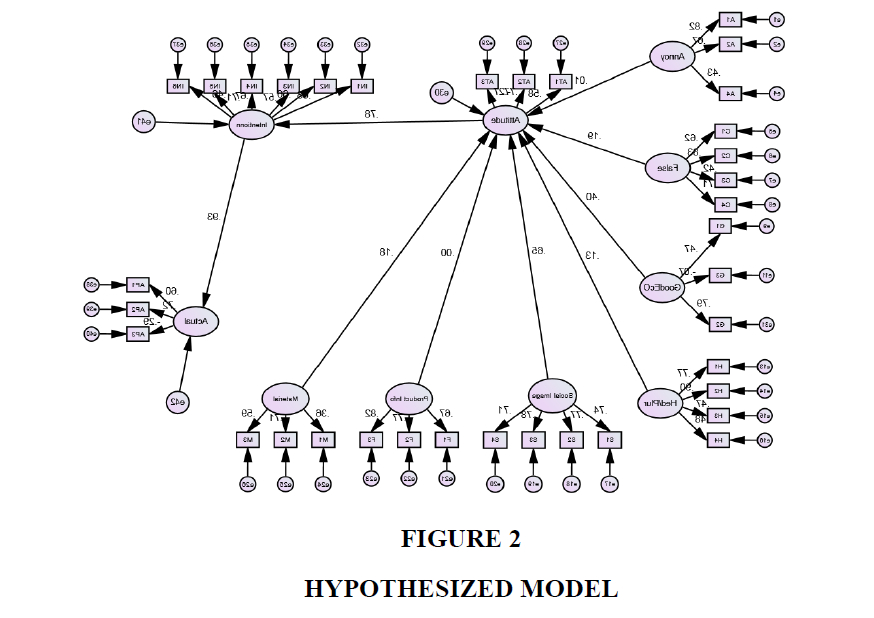

Maximum likelihood was adopted, in order to test the proposed structural model. Maximum Likelihood was used because it provides unbiased, more consistent, and more efficient parameter estimate (Kmenta, 1971; Jaccard & Wan, 1996). The key factor in evaluation of any model is goodness-of-fit indices of that model. This is through using structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS providing estimation of goodness-of-fit indices as shown in Figure 2. The most common measure of model goodness-of-fit is Chi-square/Degrees-of-freedom (CMIN/DF). The value of (CMIN/DF) ratio should not exceed 5 (Bentler & Bonnett, 1989). These are summarized in Table 3 with its reference of goodness-of fit.

| Table 3 Correlated Latent Variables | ||||||||||

| Annoying | Falsity | Goof for Economy | Hedonism/ Pleasur |

Materials | Product Information | Social Role and Image | Attitude | Intention towards Advertising through | Actual Purchase | |

| Annoying | 0.638 | |||||||||

| Falsity | 0.654** | 0.645 | ||||||||

| Goof for Economy | -0.19* | 0.016 | 0.054 | |||||||

| Hedonism/ Pleasur |

-0.52 | 0.189* | 0.495** | 0.654 | ||||||

| Materials | 0.254** | 0.381** | 0.311** | 0.395** | 0.555 | |||||

| Product Information | -0.09 | 0.184* | 0.457** | 0.618** | 0.531** | 0.751 | ||||

| Social Role and Image | 0.157 | 0.415** | 0.352** | 0.604** | 0.552** | 0.645** | 0.749 | |||

| Attitude | -0.36 | 0.187* | 0.430** | 0.479** | 0.303** | 0.441** | 0.551** | 0.673 | ||

| Intention towards Advertising through | 0.218** | 0.513** | 0.352** | 0.555** | 0.515** | 0.529** | 0.682** | 0.449** | 0.5 | |

| Actual Purchase | -0.123 | 0.061 | 0.348** | 0.442** | 0.257** | 0.428** | 0.419** | 0.453** | 0.526** | 0.5 |

Note: The values on the diagonal line (the shadowed parts) are the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The remaining values are the squared of the study variables correlation coefficients.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) aims to ensure that the set of connections between observed (measured) variable and its unobserved (latent) variable can measure and predict the variance of this unobserved (latent) variable. According to Figure 2, the modified hypothesized model consisted of ten measurement models: AN (Annoying) measurement model, FAL(Falsity) measurement model, GFEC (Good for Economy) measurement model, HEP (Hedonism/Pleasure) measurement model, SOI (Social Image) measurement model, PROI (Product Information), MATR (materialism) measurement model, ATTI (Attitude towards Advertising through Sports) measurement model, Intention (Intention towards Advertising through Sports) measurement model, and Actual (Actual Purchase) measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was assessed based on the measurement model by the significant critical ratio (C.R) of each item estimated path coefficient on its assigned construct factor (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

The researcher considered Hair et al. (2006) recommendations on the relative importance and significance of the factor loading of each item, (loadings greater than 0.3 are considered significant; loadings greater than 0.4 are considered important; and loadings 0.5 or greater are considered to be very significant). Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which a measure does not correlate with other constructs from which it is supposed to differ (Malhotra et al., 1996). Discriminant validity was performed by assessing whether a fit was improved when any pair of constructs was collapsed into a single factor. The (AVE) is the amount of variance captured by the measurement model versus the amount due to measurement errors. The (AVE) was adopted to assess discriminant validity by examining whether the squared of correlation coefficient between two variables less than the average extracted (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As for Average variance extracted (AVE) it could be calculated by (summation of squared factor loadings)/[(summation of squared factor loadings) + (summation of error variances)]. It has been suggested that AVE should be not less than 0.5 to demonstrate significant variance captured by the measurement model (Fornell & Larker, 1981). Table 2 shows that AVE values met the recommended level for all constructs.

Reliability is concerned with the question of whether the results of a study are repeatable. Reliability analysis does not ensure unidimensionality but merely presuppose its existence. Through theoretical justification and the constructs having been operationalized, Cronbach’s Alpha (’) was chosen to analyze the degree of consistency among the items in a construct. Cronbach Alpha was developed by Cronbach in 1951 as a generalized measure of the internal consistency of a multi-item scale. Researchers agreed that an alpha coefficient would range between 0.5-0.7 which is considered to be a moderate and acceptable level for social science research. According to Nunnally & Bernstein (1978), reliability alpha coefficient should not be less than 0.5. It is always recommended to have alpha coefficient value high because the higher the coefficient the better the reliability of the construct scale.

The reliability values for all constructs (not less than 0.5) are within the acceptable level of the alpha coefficient Table 2. While the overall reliability for the scale was above 0.9 which indicates high degree of consistency among the items in a construct.

Table 3 presents the average variance extracted (AVE), Standard factor loading (SFL), critical ratio (C.R), Square Multiple correlation (SMC), composite reliability, reliability coefficient (’).

The above Table 3 shows that, the average variance extracted by the correlated latent variables is greater than the square of the correlation between the latent variables which also indicates sufficiency of discriminant validities.

The following Table 4 summarizing the results of research hypotheses testing:

| Table 4 Regression Weights and Hypotheses Testing | |||||||

| Sample size (n=146) | |||||||

| # | Path direction | Standardized Regression Weights | Sig. | C.R | H0 | ||

| AN | ® | ATTI | 0.009 | 0.918 | 0.103 | Supported | |

| FAL | ® | ATTI | 0.188 | 0.034 | 2.116 | Supported | |

| GFEC | ® | ATTI | 0.398 | 0.002 | 3.064 | Supported | |

| HEP | ® | ATTI | 0.132 | 0.108 | 1.609 | Supported | |

| SOI | ® | ATTI | 0.648 | *** | 5.078 | Rejected | |

| PROI | ® | ATTI | 0.000 | 0.999 | -0.001 | Supported | |

| MATR | ® | ATTI | 0.183 | 0.072 | 1.798 | Supported | |

| ATTI | ® | Intention | 0.776 | *** | 5.180 | Rejected | |

| Intention | ® | Actual | 0.932 | *** | 5.824 | Rejected | |

| AN (Annoying), FAL(Falsity), GFEC (Good for Economy) , HEP (Hedonism/Pleasure), SOI (Social Image), PROI (Product Information ), MATR (MATERILAS ), ATTI (Attitude), Intention (Intention towards Advertising through Sports ), Actual (Actual Purchase). (*) Means that the results according to the modified model. | |||||||

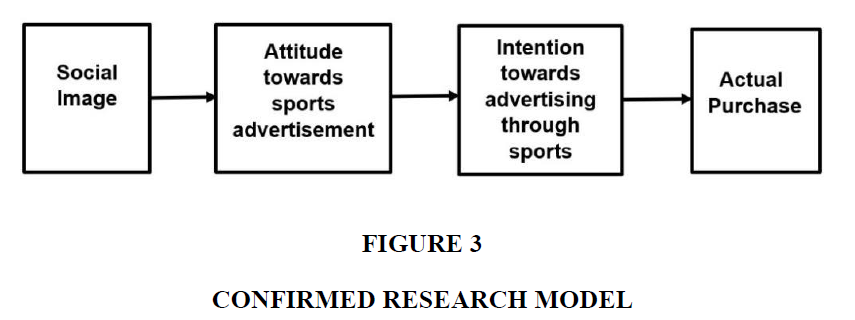

According to hypothesized model analysis Table 4 shows that only ’SOI (Social Image)’ has a positive impact on ’ATTI (Attitude towards Advertising through Sports)’ (.648) with a high level of significance (*** p<0.001). Additionally, ’ATTI (Attitude towards Advertising through Sports)’ has a positive effect on ’Intention (Intention towards Advertising through Sports) (0.776) with a high level of significance (*** p<0.001). Finally, the model confirmed the positive effect of ’Intention (Intention towards Advertising through Sports) on ’Actual (Actual Purchase)’ (0.776) with a high level of significance (*** p<0.001). Table 5 shows that most of the model fit indices were met (CMIN/DF 0.124, RMSEA 0.052, CFI 0.963 and others).

| Table 5 Model Fit Indices | ||

| Confirmatory Factor Analysis CFA (Goodness-of-fit measure) | Recommended Value | Value |

| Chi-Square (CMIN) | - | 1434.093 |

| Degree of freedom | - | 585 |

| P value | P ≤ 0.05 (Hair et al., 2006) | 0.124 |

| CMIN/DF | Chi square/ df ≤ 5 (Bentler & Bonnett, 1989) | 2.451 |

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | ≥ 0.90 (Hair et al., 2006) | 0.963 |

| Root mean square error of approximate (RMSEA) | Value of about 0.08 or less for the RMSEA would indicate a reasonable fit. < 0.08 (Hair et al., 2006) | 0.052 |

| Normal fit index (NFI) | ≥ 0.90 (Hair et al., 2006) | 0.902 |

Accordingly, based on the analysis the confirmed research model is as follows (Figure 3):

Conclusion

Gender has been studied in several research topics and fields due to its importance especially in psychology, marketing and behavioral studies (Putrevu, 2004; Richard et al., 2010). In marketing, gender is an important demographic variable that is used by marketers as a base for segmentation of markets (Darley & Smith, 1995). Accordingly, gender studies are vital for advertisers to highlight gender differences in order to effectively implement optimal advertising design features and relevant products according to gender preferences. This study was conducted aiming at empirically testing the impact of sports advertisement on Saudi females purchase decisions. This study adopted Pollay & Mittal (1993) conceptualized model of attitude towards advertising through sports. According to the literature, results were different based on different cultures. According to American and Singaporean cultures, product information, hedonism had direct impact on determining consumers’ attitudes towards advertising through sports (Pyun et al., 2012; Cho et al., 2020). As for other cultures such as Turkey, social role & image, hedonism/pleasure, annoyance/irritation and product information were significant. On the other hand, according to Bauer & Greyser (1968) annoyance/irritation and Falsity/ no sense have been viewed as different concepts. Consumers consider advertising as annoying/irritating based on ’stimulus qualities’ of advertisement or considering advertisement as being too long or noisy. Several studies investigated the impact of annoyance and irritation with advertising in general and other studies investigated annoyance and irritation through advertising through sports. Results revealed that sports fans are irritated with too much advertising during sports events (Lefton, 1997). Consumers perceive advertising as irritating and annoying when advertisers adopt intrusive tactics that annoy or offend (Zhang, 2000; Rettie et al., 2002) or when the same advertisement were shown repeatedly and too frequently. According to Bauer and Grayser (1968) ads may be considered as annoying because these ads direct irritation as unpleasant events in one’s daily life, and less because they fail to give accurate or interesting marketing information to customers or engender moral concern. These previous studies are in line with Popovic (2019) study where social role/ image, hedonism and annoyance significantly influenced students’ attitudes towards advertising through sports. Accordingly, the researchers added annoyance/irritation & falsity/no sense to be investigated based on the previous studies that showed the negative roles of advertising through sports as in annoyance /irritation & falsity/no sense constructs but in this study such constructs had no impact on consumers’ attitudes towards advertising through sports and only social image had the direct impact on Saudi females’ attitudes towards advertising through sports. The results provide a valuable interpretation for international and national organizations to direct their advertisement through sports events and sponsorship. The study direct entrepreneurial marketing efforts towards females as being considered a new segment that was not targeted before in KSA.

While our research has valuable contribution based on the novelty of the study, it has some limitations. One of the limitations is conducting a cross sectional survey because it makes it difficult to identify the direction of causality. Moreover, the sample drawn was from the main capital city (Riyadh) based on two main famous female fitness clubs. It would be suggested to consider other cities for further investigation. It is suggested to do further studies research to understand about sport fans and spectators and to identify their motivation to attend, watch or participate in a sport event. The motives of consumers will differ based on the type of sports whether artistic sports such as gymnastics & synchronized swimming or combative sports such as wrestling, football and boxing. Further research may be conducted to examine females’ attitude towards certain brands and its impact on their behavior towards sports advertising.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research DAR ALULOOM UNIVERSITY.

References

- Abd Aziz, N., Mohd Yasin, N., & Syed A. Kadir, B. S. L. (2008). Web advertising beliefs and attitude: Internet users’ view. The Business Review, Cambridge, 9(2), 337.

- Alharbi, K. K., Syed, R., Alharbi, F. K., & Khan, I. A. (2017). Association of Apolipoprotein E polymorphism with impact on overweight university pupils. Genetic testing and molecular biomarkers, 21(1), 53-57.

- Alwitt, L. F., & Prabhaker, P. R. (1994). Identifying who dislikes television advertising: Not by demographics alone. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(6), 17-30.

- Alwitt, L. F., & Prabhaker, P. R. (1992). Functional and beliefs dimensions of attitudes to television advertising: Implications for copytesting. Journal of Advertising Research, 32 (5), 30-42.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411-423.

- Bauer, R. A., & Greyser, S. A. (1968). Advertising in America: The consumer view. Boston: Harvard University Press. Dissertation, Boston, MA: Harvard University.

- Belch, G., & Belch, M. (2008). Advertising and promotion: An integrated marketing communication perspective. CA: McGraw-Hill.

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1989). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological bulletin, 88(3), 588.

- Bhargava, M., Donthu, N., & Caron, R. (1994). Improving the effectiveness of outdoor advertising: Lesson from a study of 282 campaigns. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(2), 46-55.

- Biswas, A. (1992). The moderating role of brand familiarity in reference price perceptions, Journal of Business Research, 25, 69-82.

- Burns, K. S. (2003). Attitude toward the online advertising format: A reexamination of the attitude toward the ad model in an online advertising context. Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Byun, K. W., & Kim, S. (2020). A Study on the Effects of Advertising Attributes in YouTube e-sport Video. International Journal of Internet, Broadcasting and Communication, 12(2), 137-143.

- Cartwright, J., McCormick, H., & Warnaby, G. (2016). Consumers’ emotional responses to the Christmas TV advertising of four retail brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 82-91.

- Cho, H., & Leng, H. K. (2020). Applicability of belief measures for advertising to sponsorship in sport. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 21(2), 352-369.

- CNN (2020). Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2020/02/25/football/saudi-arabia-football-league-women-rights-intl/index.html

- Cocker, H. L., Banister, E. N., & Piacentini, M. G. (2015). Producing and consuming celebrity identity myths: unpacking the classed identities of Cheryl Cole and Katie Price. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(5-6), 502–524.

- Cowley, E., Page, K., & Handel, R. H. (2000). Attitude toward advertising implications for the World Wide Web. Proceedings of Australian & New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, 463-467.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334.

- Darley, W. K., & Smith, R. E. (1995). Gender differences in information processing strategies: an empirical test of the selectivity model in advertising response. Journal of Advertising, 24(1), 41-56.

- Donthu, N., Cherian, J., & Bhargava, M. (1993). Factors influencing recall of outdoor advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 33(3), 64-72.

- Ducoffe, R. H. (1995). How consumers assess the value of advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 17(1), 1-18.

- Ducoffe, R. H. (1996). Advertising value and advertising on the web. Journal of Advertising Research, 9, 21-35.

- Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of marketing management, 15(4), 291-314.

- Fillis, I., & Mackay, C. (2014). Moving beyond fan typologies: The impact of social integration on team loyalty in football. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(3-4), 334–363.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 39-50.

- Friedmann, R., & Zimmer, M. R. (1988). The role of psychological meaning in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 17(1), 31-40.

- Haghirian, P., & Madlberger, M. (2005). Consumer attitude toward advertising via mobile devices: An empirical investigation among Austrian users. Proceedings of European Conference on Information Systems, Regensburg, Germany.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis. Auflage, Upper Saddle River.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M, & Sarstedt, M. (2016). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet: Theory and Practice. Journal of Marketing, 19(2), 139-152.

- Jaccard, J., & Wan, C. (1996). Lisrel approach to interaction effects in multiple regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Jayasingh, S., & Eze, U. C. (2012). Analyzing the intention to use mobile coupon and the moderating effects of price consciousness and gender. International Journal of Electronic Business Research, 8(1), 54-75.

- Justin, P., & Shailja, B. (2018). Does Celebrity Image Congruence Influences Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention’, Journal of Promotion Management, 24(2), 153-177.

- Keshkar, S., Lawrence, I., Dodds, M., Morris, E., Mahoney, T., Heisey, K. & Faruq, A. (2018). The role of culture in sports sponsorship: An update. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 7(1), 57-81.

- Kmenta, J. (1971). Elements of econometrics. New York, NY: McMillan Publishing Company.

- Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: a meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), 55-75.

- Korgaonkar, P. K., Karson, E. J., & Akaah, I. (1997). Direct marketing advertising: The assents, the dissents, and the am bivalents. Journal of Advertising Research, 37, 41-55.

- Korgaonkar, P., Silverblan, R., & O’Leary, B. (2001). Web advertising and Hispanics. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(2), 134-152.

- Landes, W. M., & Posner, R. A. (1987). Trademark law: An economic perspective, Journal of Economics, 30, 265-309.

- Lefton, T. (1997). ESPN, Fox commit to virtual signage. Brand Week, 10(38), 8.

- Lutz, R. (1985). Affective and cognitive antecedents of attitudes toward advertising: a conceptual framework. In Alwitt, L. and Mitchell, A. (Eds.), Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects: Theory, Research and Applications pp. 45-63. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Malhotra, N. K., Agarwal, J., & Peterson, M. (1996). Methodological issues in cross’cultural marketing research. International marketing review, 13(5), 37.

- Martinez-Lopez, F. J., Luna, P., Martinez, F. J. (2005). Online shopping, the standard learning hierarchy, and consumers’ internet expertise. Internet Research, 15(3), 312-334.

- Mehta, A. (2000). Advertising attitudes and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 40(3), 67-72.

- Mittal, B. (1994). Public assessment of TV advertising: Faint praise and harsh criticism. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(1), 35-53.

- Munusamy, J., & Wong, C. H. (2007). Attitude towards advertising among students at private higher learning institutions in Selangor. UniTAR e-Journal, 3, 31-51.

- Neuman, L. W. (2002). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Pearson.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1978). Psychometric Theory McGraw-Hill New York. The role of university in the development of entrepreneurial vocations: a Spanish study.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1967). Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill Inc. New York.

- Patwardhan, P., & Ramaprasad, J. (2005). Rational integrative model of online consumer decision making. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 6(1), 2-13.

- Petrovici, D., Marinova, S., Marinov, M., & Lee, N. (2007). Personal uses and perceived socialand economic effects of advertising in Bulgaria and Romania. International Marketing Review, 24, 539-562.

- Pollay, R., & Mittal, B. (1993). Here’s the beef: factors, determinants, and segments in consumer criticism of advertising. Journal of Marketing, 57, 99-114.

- Popovic, S. (2019). Beliefs about the influence on attitudes of turkish university students toward advertising through sport. Sport Mont, 17(2), 9-15.

- Putrevu, S. (2004). Communicating with the sexes: male and female responses to print advertisements. Journal of Adertising, 33(3), 51-62.

- Putrevu, S., & Lord, R. K. (1994). Comparative and noncomparative advertising: attitude effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions. Journal of Advertising, 23(2), 77-90.

- Pyun, D. Y. (2006). Proposed model of attitude toward advertising through sport. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Tallahassee: The Florida State University.

- Pyun, D. Y., & Kim, J. (2004). An examination of virtual Advertising exposure on Major League Baseball games: Comparing to in-stadium advertising exposure by a content analysis. Korea Sport Research, 15(1), 683-694.

- Pyun, D. Y., Kwon, H. H., Chon, T. J., & Han, J. W. (2012). How does advertising through sport work’ Evidence from college students in Singapore. European Sport Management Quarterly, 12(1), 43-63.

- Rettie, R., Robinson, H., & Jenner, B. (2002, March). Does Internet advertising alienateusers’ Proceedings of the meeting of Academy of Marketing.

- Richard, M., Chebat, J. C., Yang, Z., & Putrevu, S. (2010). A proposed model of online consumer behavior: Assessing the role of gender. Journal of Business Research, 63(910), 926-934.

- Richins, M. L. (1991). Social comparison and the idealized images of advertising. Journal of consumer research, 18(1), 71-83.

- CEDA (2016). Saudi Council of Economic and Development Affairs. Saudi vision 2030.

- Schlosser, A. E., Shavitt, S., & Kanfer. (1999). A survey of internet users’ attitudes toward internet advertising. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 13(3), 34–54.

- Singh, R., & Vij, S. (2007, April). Socio-economic and ethical implications of advertising-A perceptual study. Proceedings of International Marketing Conference on Marketing & Society, pp. 8-10.

- Spears, N., & Singh, S.N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 26(2), 53-66.

- Tan, S. J., & Chia, L. (2007). Are we measuring the same attitude’ Understanding media effects on attitude towards advertising. Marketing Theory, 7(4), 353-377.

- Taylor, S. A., & Hunter, G. L. (2002). The impact of loyalty withe-CRM software and e-services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13(5), 452-478.

- Tharp, M., & Scott, L. M. (1990). The role of marketing processes in creating cultural meaning. Journal of Macromarketing, 10(2), 47-60.

- Turley, L., & Shannon, J. (2000). The impact of effectiveness of advertisements in a sports arena. Journal of Service Marketing, 14(4), 323-336.

- Wang, C. J., Chatzisarantis, N. L., Spray, C. M., & Biddle, S. J. (2002). Achievement goal profiles in school physical education: Differences in self’determination, sport ability beliefs, and physical activity. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(3), 433-445.

- Wang, J. C., Liu, W. C., Lochbaum, M. R., & Stevenson, S. J. (2009). Sport ability beliefs, 2 x 2 achievement goals, and intrinsic motivation: The moderating role of perceived competence in sport and exercise. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 80(2), 303-312.

- Wang, Y., & Sun, S. (2010). Examining the role of beliefs and attitudes in online advertising: A comparison between the USA and Romania. International Marketing Review, 27(1), 87-107.

- Wann, D. L., Hackathorn, J., & Sherman, M. R. (2017). Testing the team identification–social psychological health model: Mediational relationships among team identification, sport fandom, sense of belonging, and meaning in life. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 21(2), 94-107.

- Watkins, L., Aitken, R., Robertson, K., & Thyne, M. (2016). Public and parental perceptions of and concerns with advertising to preschool children. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(5), 592-600.

- Wolin, L. D., & Korgaonkar, P. (2005). Web advertising: gender differences in beliefs, attitudes, and behavior, Journal of Interactive Advertising, 6(1), 125-136.

- Yee, K. P., & Eze, U. C. (2012). The influence of quality, marketing, and knowledge capabilities in business competitiveness. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 11(3), 288-307.