Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 3

Saudi Arabian Female Startups Status Quo

Rahatullah, M.K

Effat University

Abstract

The article proposes a methodology for assessing the competitive position of the university in the market of educational services, based on the development and application of the model of mutual influence of the factors of the university's competitiveness. An algorithm for assessing competitiveness is presented. The indicators of the activity of the higher educational institution that have the greatest impact on the competitive position of the university are highlighted according to the Pareto principle. A cognitive map of the situation that determines the mutual influence of the factors is constructed. A simulation model based on the integration of the principles of system dynamics and cognitive modeling, which allows the balancing of values of key parameters, is developed. The values of the model variables during the experiments can be changed, while determining the sensitivity of the vector of output parameters. Using a method based on specifying control points, a scale of characteristics for each factor has been developed. The results of modeling on the basis of real data are presented.

Keywords

Female Start-Ups, Saudi Arabia, Status Quo.

Introduction

There is general agreement among management practitioners and researchers that successful new ventures contribute to employment, political and social stability, innovation and competition (Thurik & Wennekers, 2004; Zedtwitz, 2003; Hoffman et al., 1998; and Dunkelberg, 1995). Similarly, the success of small and medium enterprises (SME’s) is also largely attributed to entrepreneurial activities (Dyer and Ha-Brookshire, 2008).

Entrepreneurship has also become a defining business trend in many countries. We know that entrepreneurship is most successful in an ecosystem where it is supported at both the strategic level (by governmental organizations) and the institutional level (Khan, 2013a). The long list of entrepreneurs world-wide now contains a sizable contingent of women (Dechant and Al-Lamky, 2005). As a result, research into the pathways of entrepreneurship as a general phenomenon, as well as a career option for women, has flourished in recent years (see, for example, Dechant and Al-Lamky, 2005; Minniti 2010). However, very little of this research has focused on female entrepreneurs in Arab countries, where now private enterprises (SME’s and entrepreneurial ventures) are viewed as a way for these nations to reduce their reliance on oil and dependence on an expatriate workforce.

Many authors argue that women entrepreneurs can be instrumental in developing emerging economies. However, it is noticed that there is a lack of studies that can be used to assess the experience of women entrepreneurs in Arab countries – especially Saudi Arabia. A study conducted to understand women entrepreneurship in UAE and Saudi Arabia (Al Lamky 2005). However, the number of studies and the context of the research on Arab women have been limited.

Literature Review

Studies on Women Entrepreneurship in the Arab Region

The literature has often ignored the role of values in determining the choices of women entrepreneurs. Studies such as Gennari and Lotti (2013) and Fagenson (1993), asserted that women join the work force out of a need for achievement and respect in society. Recent studies show a major factor influencing women entrepreneurs is the level of constraints for women in the workforce (Elisabeth and Berger 2016. In some countries women have no access to capital or bank loans, while men have this advantage (Lilia 2014).

Education and Employment

A recent report from the World Bank (2012) analysed data from over 5000 companies in the Middle East and found that women owned approximately 13% of all firms and of these female- owned firms, only 8% were micro firms (with <10 employees), while over 30% had more than 250 employees. There appears to be a relationship between education and entrepreneurial activity. The 2012 GEM Report on women entrepreneurs demonstrated that in most regions, women entrepreneurs are more likely to have post-secondary education than women who are not entrepreneurs (30% vs. 26% for MENA/Mid-Asia) and more likely than male entrepreneurs (30% vs. 26% for MENA/Mid-Asia). For a comparison, 70% of female entrepreneurs in the U.S. and 55% in Israel have a post-secondary degree (Minniti, 2010). This agrees with work of Mark et al. (2006) who found that the average level of education among women entrepreneurs in developed countries was higher than their counterparts in developing countries, including Arab nations. Earlier studies, like Aldrich et al., 1998 had been inconsistent about education and business ownership. Sharpe and Schroeder (2016) analyzed data from the World Bank and found that unemployment among women in the Middle East is relatively high, although it differs by country. It has been lower over the past five years in Lebanon, Israel and Qatar (2-12%), compared to Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan (14-28%).

Unemployment rates arise from numerous challenges that women face in the Middle East. These insights combined with the restrictions for women in banking and ownership make starting companies more difficult for women than for men.

Culture and Women Entrepreneurship in Arab Countries

Previous studies have revealed that culture is an important factor used to explain variations in entrepreneurship among societies (Cornwall, 1998; Wennekers et al., 2001; Dechant and Al-Lamky, 2005). In Arab countries, in particular, women participation in the labor force is influenced by culture, as well as by Islamic principles. The Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) study pointed to some cultural practices that might prevent women from conducting their business as compared to men. Nilufer’s (2001) work on socio-cultural factors in developing countries showed that there is a social influence on women's decision to become an entrepreneur. Such socio-cultural factors could be religious values, ethnic diversity and marital status. However, Carswell and Rolland (2004) did not find any relationship between socio-cultural factors, such as religious values, ethnic diversity and the reduction in business start-up rate.

Salehi-Isfahani (2000) noticed that married women in developing countries are less likely to participate in the country's labour force. Her study established that married women have the lowest participation rate in the Iranian labour force. Similarly, Assaad and El-Hamidi (2002) found that female participation in Egypt is significantly less for married women. Shah and Al-Qudsi (1990) concluded that single women participation is almost twice as much as married women participation in the Kuwaiti labour force.

Ram (1996) determined that women entrepreneurs felt overloaded with domestic responsibilities. The findings showed that 43.20% did not get any help for domestic responsibilities, whereas 37% received some help and 20% received help to a large extent.

Among the persons rendering assistance in domestic responsibilities, maids were the primary source of help (25%). Among the family, husbands rendered help in setting up businesses in 12% of the cases followed by children in 11% of the cases. In a study on home-based women entrepreneurs living in Ankara city (Ozgen and Ufuk, 1998), it was determined that 63% of the women did not get any help for domestic responsibilities. In addition to domestic responsibilities, the lack of time available due to family commitments has been documented as a constraint in studies conducted by Karim (2000) in Bangladesh and de Groot (2001) in Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Mali and Morocco.

Finally, the external support for entrepreneurs varies by culture. Developing countries lack effective women organizations that enhance their own decision-making. Zewde and Associates (2002) pointed out that the absence of appropriate and effective women entrepreneurs' organizations and associations have a negative effect on women enterprise development. Availability and use of money is a significant cultural challenge due to social position and family commitments of women in the Arab world as Carter et al. (2001) showed that women entrepreneurs find it difficult to raise the start-up capital. Ngozi (2002) demonstrated that since women do not have the required wealth, they cannot secure the required collateral to obtain a bank's loan. In addition, their social position limits their ability to establish a financial network and good relationships with banks, due to gender discrimination and stereotyping.

Motivational Factors

Different factors motivate a woman to become an entrepreneur. Robinson (2001) referred to the push and pull factors. The push factor is associated with negative conditions, while the pull factor is attributed to positive developments. Examples of push factors include low household income, job dissatisfaction, strict working hours or even a lack of job opportunities. The pull factors on the other hand include the need for self-accomplishment and the desire to help others. Dhaliwal (1998) found the push factor to be evident in developing countries, while Orhan and Scott (2001) showed evidence that women entrepreneurs in developing countries were motivated by a combination of push and pull factors. They suggested earning money, family tradition, higher social status, self-employment, economic freedom, as the major pull factors, whereas a lack of education, dissatisfaction in current job and family economic hardship were identified as the push factors.

Empirical evidence on Bahrain and Oman in the study by Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) showed pull factors, such as opportunities, the need for achievement, self-fulfilment and a desire to help others, motivated women become entrepreneurs in most of cases. Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) found that achievement was the primary driver for self-employment among the Bahraini and Omani female entrepreneurs. The scholars assert that this could be attributed to their relatively high socioeconomic status and educational levels. It might also be reasoned, however, that in Arab countries which are high in Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance and low in Individualism, women have "more difficulties in doing things their way since existing organizations and structures are less suited for them" (Wennekers et al., 2001). Study subjects may have chosen self-employment to meet their need for achievement in a society imbued with organizational and cultural constraints regarding the potential of women.

Enterprise Characteristics

Coleman (2002) asserted that women tend to mainly participate in the services sector and confirmed by Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) who found that Bahraini and Omani women entrepreneurs chose the services sector for their investment. Previous experience, availability of opportunities, economics and cultural influencers affected women entrepreneurs' decisions.

Another factor dictating women's decisions to become entrepreneurs is the size of the business enterprise. Since women entrepreneurs are attracted to the services sector, the size of their businesses is relatively small. Women entrepreneurships are relatively small in size and are likely to employ fewer numbers of people mainly between 5 and 25. (Coleman, 2002; Robb, 2002; Dechant and Al-Lamky, 2005). The latter study also identified use of social media as another characteristic of Arab women enterprises. Numerous examples exist of women using the Internet to start firms that engage in e-commerce to sell anything from clothing, to food, to educational services (see for example, Sharpe and Schroeder, 2016).

Another characteristic of female start-ups is their important use of “soft skills”. Riley (2006) and Heltzel (2015) demonstrated the importance of soft skills for start-ups and identified training regimes, where training is defined specifically by others as the development of knowledge, skills and/or attitudes required to perform adequately a given job (Armstrong, 2001; Sonmez, 2015). Stuart (2013) highlighting importance of soft skills stated that human resources workshops in training and development are important to provide employees continuous improvement in their skills and attitudes. Human Resources training ensure that the company’s optimal performance is achieved through leveraging human capital and aligning skills and performance with organizational goals (Elaine, 2002; Houghton and Prosico, 2001). A company with employees aligned on goals for the future is able to reach those accomplishments faster (Frost, 2013). These studies identify numerous soft skills required by start-ups, ranging from basic business planning to financial feasibility analysis and sophisticated business strategic skills. A number of studies, such as Kaiser and Muller (2015); Nunez (2015); Markku et al. (2005), identified numerous start-up, marketing, management and social skills necessary for start-ups; a total of 17 commonly stated skills encompass the above areas. These skills include communication, supervision, problem solving, leadership, conflict resolution, team working, flexibility, creativity, assertiveness, diplomacy, counselling, coaching and mentoring, negotiating and influencing, branding, sales and marketing, relationship building and networking.

The Gap and Research Questions

The studies have often ignored the role of values in determining the choices of women entrepreneurs. Scholars and practitioners assert push and pull factors (Sonmez, 2015) or combination of these factors, (Nasser and Nuseibah, 2009) that bring women into the work force. The following factors (Fergany, 2002, Assad and Al-Hamidy, 2002; Hatun and Ozgen, 2001) have been identified as important to know the values and subtleties of women entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia.

• Education

• Employment

• Culture

• Motivational factors

• Enterprise characteristics

The Hofstede cultural dimension index (https://geert-hofstede.com/saudi-arabia.html) rates the kingdom as 60 in masculinity and 95 in Power distance index. This shows that the Saudi Society is masculine and women have little say and are a hugely dependent upon male population. Therefore, keeping the above in view the following research questions are formulated and answers would be sought using the below mentioned mixed methods study of 80 female start-ups from across Saudi Arabia.

1. Has the role of society, including family members has changed over the period of time and what is the part they play in female start-up development in Saudi Arabia?

2. What is the effect of changing cultural values on female start-ups?

3. Saudi Arabia is among the rich economies of the world and is member of G20 nations, denoting its high GDP. Therefore, it will be interesting to see how are Saudi female start-ups different in deciding to become an entrepreneur?

4. The entrepreneurship ecosystems are dynamic and play vital role in entrepreneurial activities and development of SME’s. Hence, a question arises that keeping in view cultural dimensions on power distance and masculinity, how the ecosystem is supporting the women of the country to start their business.

Methods

Prior research shows that there is a lack of information on female entrepreneurship in Arab nations. We identified a number of areas, where more research is needed. These include: nature of the businesses started by women; roles of family, motherhood, spouse and society in the business; underlying motivations of female start-ups; assistance provided by Entrepreneurship Ecosystem stakeholders; and challenges faced by female entrepreneurs. This information is lacking not only for the Middle East, but more specifically for Saudi Arabia. Thus, we explore vital values, characteristics and features of female entrepreneurship in the Saudi context.

Given the difficulties associated with reaching out to female start-ups in Saudi Arabia, we placed a structured questionnaire on-line (using SurveyMonkey) with a target sample of 50 diverse female entrepreneurs from across Saudi Arabia. The survey instrument was designed to measure the values, characteristics, motivations, skills required, challenges and features of female start-ups in Saudi Arabia. Once the survey was posted, we asked the chambers of commerce in Jeddah, Riyadh, Madina Al Munawwara, Khobar, Tabuk and Makkah Al Mukarramah, to help secure responses from female start-ups. Some female start-ups known to the authors were also contacted.

This outreach was necessary for two reasons. First, numerous studies including MR Khan (2013); Assad and El Hamidi (2002); Baker, Gedajlovic and Lubatkim (2005) pointed out the issues in reaching out to respondents and particularly female respondents in the Kingdom, owing to its tradition as a closed conservative society. Second, although on the rise, the current number of established female start-ups is limited in the Kingdom, as identified by Al-Qudaiby and Rahatullah (2014) and Dechant and Lamky (2005).

Our strategy proved successful and 80 female start-ups completed the questionnaire on SurveyMonkey. The responses were then downloaded for data presentation and detailed analysis using SPSS. After the analysis had been conducted, external validity was achieved by conducting three interviews with entrepreneurs who had not responded to the survey. These established entrepreneurs have developed their businesses in the fields of event management, education and fashion. They started their businesses in the years between 2000 and 2002 in Jeddah and Riyadh – the main financial centres of the Kingdom. The names of these established female entrepreneurs are confidential and represent the fashion industry, the event management industry and the education industry.

The questionnaire included 28 structured close-ended questions in the following areas:

• Nature of business;

• Start-up status (i.e., personal status, Marital Status, Motherhood status);

• Treatment received as a woman;

• Knowledge of government agencies;

• Assistance from families and husband;

• Interaction of female start-ups with entrepreneurship ecosystem;

• Start-up challenges and motivations; and

• Attitude of society towards female start-ups.

Results and Analysis

Table 1 show the location of all 80 female start-ups who responded to the survey. The highest numbers of participating female start-ups were from Jeddah, with 23 female start-ups, followed by Riyadh with 21, Khobar with 14 and, Makkah Mukarramah with 11. The number of female start-ups from Madina Munawwara and Tabuk were fewer.

| Table 1 Respondents |

||||||

| Al Madina Munawwarah | Makkah Al Mukarramah | |||||

| Jeddah | Khobar | Riyadh | Tabuk | Total | ||

| 6 | 23 | 14 | 11 | 21 | 5 | 80 |

The questionnaire had 16 business areas identified with an option for others. However, the respondents identified themselves as belonging to seven diverse activities as shown.

The majority of female entrepreneurs in the study are married (59%) however, a noticeable number of single (25%) and divorced women (17%) also start businesses in Saudi Arabia. This might be a significant change and shift from the past. However, this cannot be substantiated, as we do not have relevant time series data. From Table 2, it is clear that women start-ups are mainly in jewellery related, spa related, clothing/boutiques, food related, beauty, event planning and graphic design industries. The result that the majority of the start-ups were founded by mothers is a surprise and is a clear shift from the past. Saudi Arabia remains tagged a conservative society, where women are more likely to remain at home and raise a family than to work outside the home. Table 3 shows that motherhood has a profound effect on women’s perceptions. An overwhelming majority agrees that motherhood leads to better leadership qualities (>75%) and the ability to multi-task (>80%). However, being a mother was perceived to have less impact on being lenient in dealing with clients or employees and being a better team manager.

| Table 2 Business Nature of Female Startups |

|

| Business Sector | Number of Respondents |

| Jewelry related | 8 |

| Spa related | 7 |

| Clothing (including Abayas) | 17 |

| Food (home cooked and restaurants) | 9 |

| Beauty related | 16 |

| Event Planning | 13 |

| Graphic Design & IT | 10 |

| Table 3 Motherhood Effects |

|||||

| Answer Options | Strongly Disagree | Do Not Agree | Maybe | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Better leadership Qualities | 10 | 2 | 7 | 33 | 28 |

| Too lenient with clients and employees | 7 | 46 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Better team manager | 8 | 34 | 9 | 15 | 14 |

| Better at Multitasking | 5 | 4 | 8 | 21 | 42 |

Table 4 provides information on the strategic stakeholders’ (government agencies) behaviour and dealings with female start-ups. The larger portion of female start-ups point out that they do not get any preferential treatment or dealing by the government offices and strategic stakeholders (validated by Khan, 2013). The response on women lobbying and support groups has been mixed; similar numbers of female start-ups recognize such efforts.

| Table 4 Ecosystem Stakeholder Dealings and Behavior with Female Start-Ups |

|||||

| Answer Options | Strongly Disagree | Do Not Agree | Maybe | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| You get preferential treatment at government offices | 6 | 46 | 21 | 5 | 2 |

| The suppliers deliver on time | 6 | 11 | 0 | 36 | 27 |

| The suppliers and other stakeholders treat women differently than men | 23 | 19 | 8 | 17 | 13 |

| The women lobbies and support groups provide help | 6 | 27 | 6 | 25 | 16 |

Table 5 identifies the support provided by non-government agencies (institutional stakeholders of the entrepreneurship ecosystem) to female start-ups, as validated in Rahatullah (2016). It is evident that the majority of female start-ups disagree that agencies provide support for children education, mentoring and transportation. However, project funding, education and business licensing services are recognized by the start-ups as available.

| Table 5 Institutional Stakeholder Dealings and Behavior with Female Start-Ups |

|||||

| Answer Options | Strongly Disagree | Do Not Agree | Maybe | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Children education support | 56 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 1 |

| Project funding | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 71 |

| Education of the entrepreneur | 5 | 15 | 37 | 11 | 12 |

| Mentoring of Entrepreneur | 13 | 51 | 17 | 7 | 0 |

| Transportation facilities | 62 | 13 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Business Training | 14 | 35 | 15 | 7 | 9 |

| Business registration | 2 | 1 | 36 | 35 | 6 |

| Business Licensing | 2 | 0 | 21 | 45 | 12 |

| Funding till business is suitable | 11 | 14 | 39 | 11 | 5 |

| Reaching beyond the demographic | 7 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 46 |

The Family and Husband Role

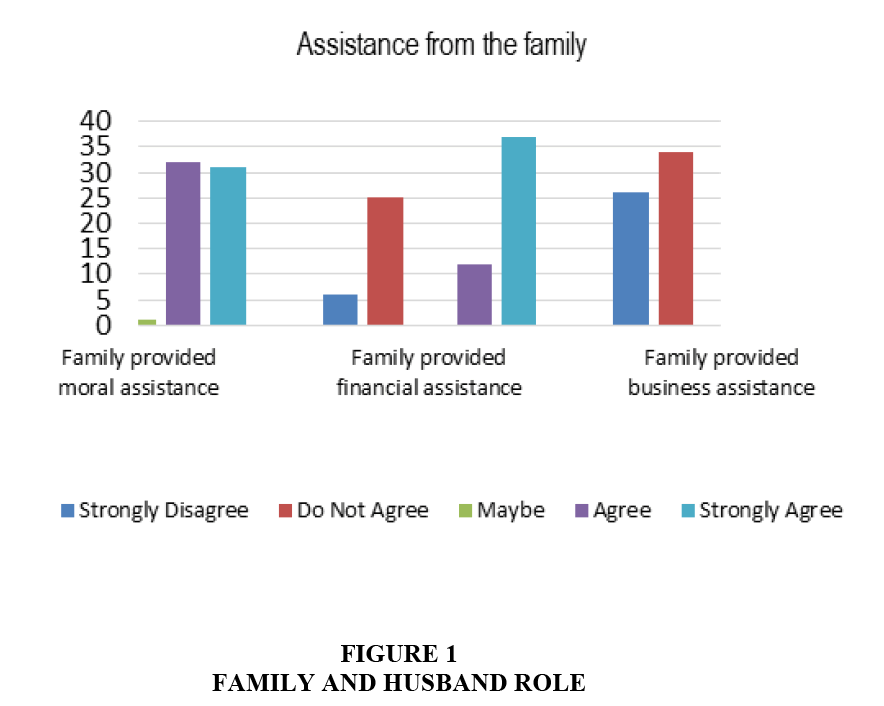

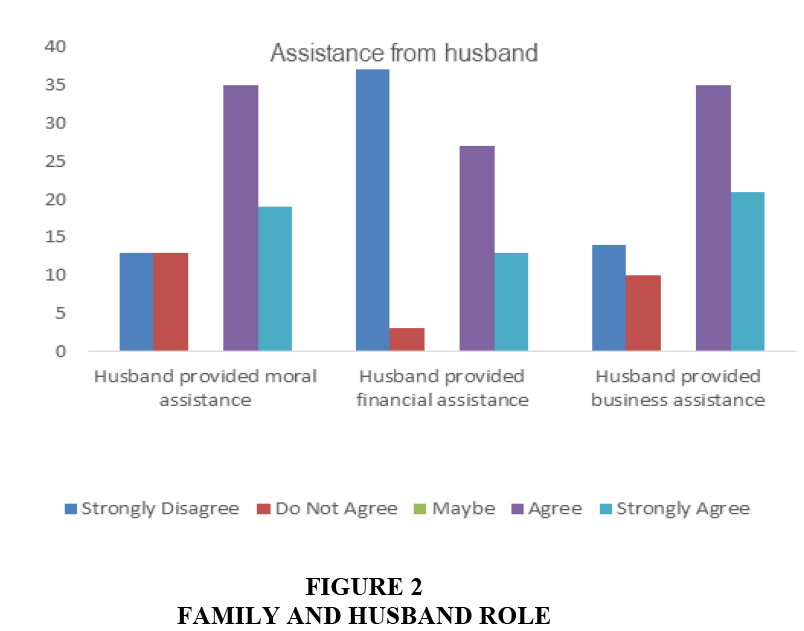

Figures 1 and 2 provide an insight into the role of families in female start-ups in Saudi Arabia. Our results seem to show the changing dynamics and variation in the social/family fabric of the society. There was a time when Saudi Arabia was known for its ultra conservative nature where the government and many of its citizens’ desire to preserve their religious values and ancient traditions (Rice, 2004). We believe the society is changing and so are the family values.

It can be seen that the majority of the female start-ups obtained moral support and financial assistance from their families; however, a number of the respondents’ assert that the families did not provide the business assistance (i.e., practical support that includes preparing plans, conducting marketing and or developing budgets). It is hence conceivable that the families do not have the relevant acumen or financial capability to assist these start-ups. It can also be understood here that the families may not have the necessary funds for the start-up or they do not wish to contribute, since organizations like the Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF) pays salaries to start-ups till the business is stable.

Our data reveal that the role of husbands appears to be substantial (where applicable), which is a noticeable shift from the past (Rice, 2004). Husbands in our sample seem to have been providing moral, financial and business assistance to their wives to establish the business.

Female Start-up Interaction with the Ecosystem

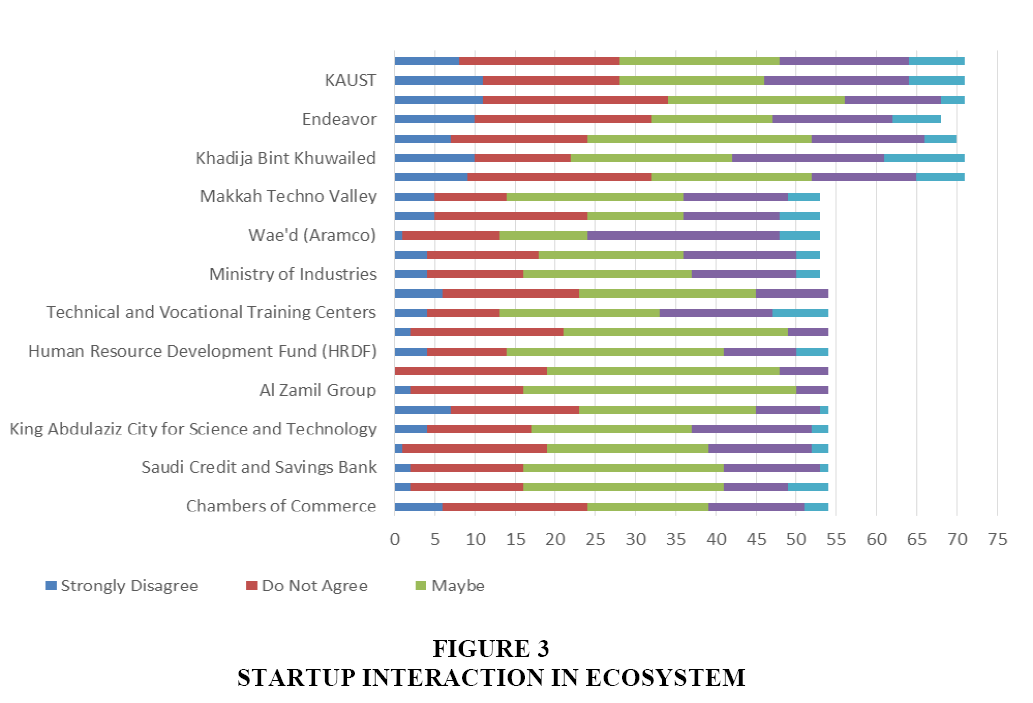

Figure 3 shows the start-up interaction with the ecosystem. A number of stakeholders in the ecosystem were identified on the survey to enable the respondents to show their recognition level and identify the assistance these organizations provide. Table 6 provides information on the organizations which may be lesser known. These organizations predominantly belong to the institutional level of the ecosystem (non-government agencies), yet a few are strategic level.

| Table 6 Information on the Stakeholder Organizations |

|||

| Organization | Work | Organization | Work |

| Injaz Al Arab | Entrepreneurial and business training to school students | Khadija Bint Khuwailed | Women advocacy and development organization |

| KAUST | King Abdullah University | Prince Sultan Fund | For start-ups and needs |

| NCB CSR | National Commercial Bank | HRDF | Human Resource Dev. Fund |

| Program | |||

| Endeavour | Start-up / angel investors | Wae’d Aramco | Aramco Start-up firm |

| Bab Rizk Jameel | CSR program of Abdul Lateef Jameel group of businesses | Techno Valley | Established by Makkah Chambers, similar to accelerator |

| Al Zamil Group | The CSR Program of the group | Centennial Fund | Funding organization |

It can be seen from the graph that the majority of the respondents claim that they either had an interaction or know Injaz, Kaust, Bank al ahli (NCB), Khadija bint Khuwalied Center, Bab Rizk Jameel, Prince Sultan Fund, Centennial Fund or the Chamber of Commerce. The organizations mentioned above are training, lending and licensing organizations, whereas, Kaust is recognized across the Middle East as a premier research organization.

The techno valleys, Kacst, etc., are less known because of the nature of their services. Most of the female start-ups are in traditional businesses that do not require high-end assistance and machinery or equipment. Since Al Zamil Group’s work is limited to a particular part of the country, therefore, it is less known among the start-ups across the Kingdom. Similarly, Technical and Vocational Training Centers (TVTC) are also male-oriented, hence fewer females know them. It is, however, surprising that the start-ups have little knowledge about the other lending institutions, such as, Al Jazira, Saudi Credit and Savings and other banks, lending institutions and funds.

Female Start-Up Challenges

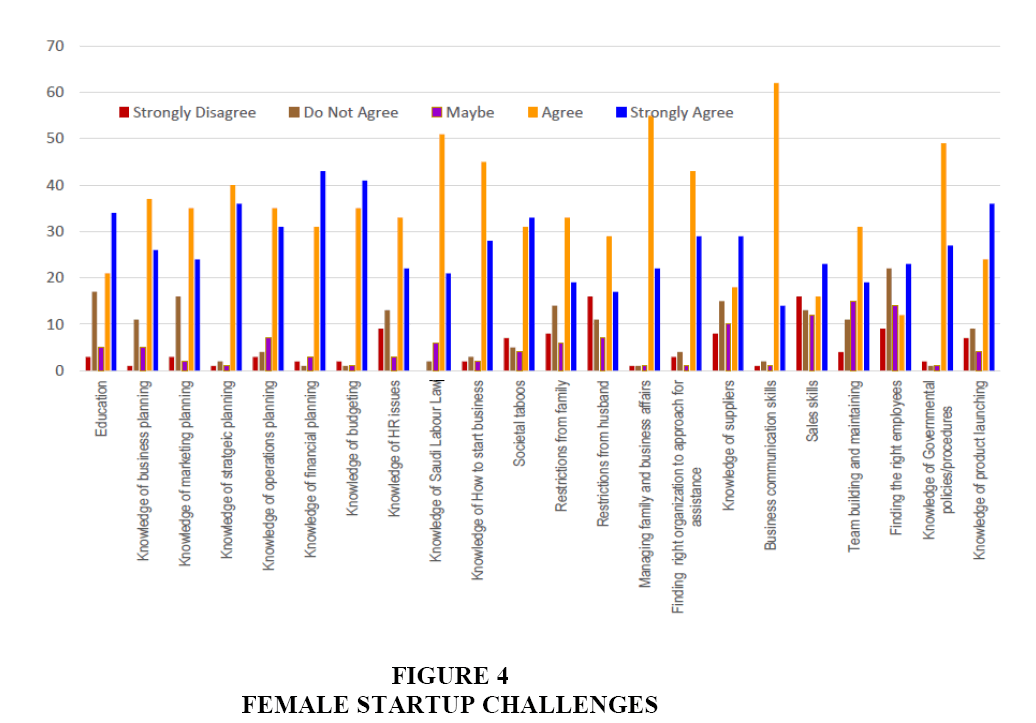

Figure 4 identifies the major challenges being faced by the female start-ups in Saudi Arabia. It can be seen that the three main challenges are communication skills, managing business and family affairs concurrently and knowledge of the Saudi labour law, respectively. Other significant issues are knowledge of how to start a business, as well as the skills needed (i.e., business and strategic planning, marketing and budgeting and the governmental policies and procedures).

These are prominent concerns of the start-ups. These findings are similar to the Saudi Arabian ecosystem study (Khan, 2013). These findings suggest that Saudi start-ups require interventions by both the strategic and institutional levels of the ecosystem to strengthen enterprise. Female start-ups have endorsed the need for soft skills incubators, training institutes, mentors and coaches. Start-ups also have shown a need for government to publicize the laws and procedures and systems more. This suggests the need from Chambers of Commerce to provide further assistance to these first-stage female entrepreneurs. This also reveals the change in the culture of the Kingdom where the openness has taken its hold and the families do not hold restrictions on female start-ups.

In order to better understand the challenges being faced by the female start-ups, a factor reduction using principal component analysis extraction method was used. The three factors arrived at in Table 7 show major areas of challenges for the female start-ups: Start-up Related, Planning and Society and Team issues.

| Table 7 Startup Challenges |

|||

| Component | |||

| Challenges | Start-up related | Planning | Society & Team |

| Education | 0.1606 | 0.0163 | 0.01 |

| Knowledge of business planning | 0.0639 | 0.1064 | 0.0079 |

| Knowledge of marketing planning | 0.0607 | 0.1267 | 0.0783 |

| Knowledge of strategic planning | 0.0607 | 0.1579 | 0.0128 |

| Knowledge of operations planning | 0.0614 | 0.101 | 0.0155 |

| Knowledge of financial planning | 0.0594 | 0.1389 | 0.0261 |

| Knowledge of budgeting | 0.0579 | 0.1067 | 0.0262 |

| Knowledge of HR issues | 0.0524 | 0.0578 | 0.1441 |

| Knowledge of Saudi Labour Law | 0.1106 | 0.0419 | 0.0113 |

| Knowledge of How to start business | 0.1059 | 0.0702 | 0.0129 |

| Societal taboos | 0.0265 | 0.0553 | 0.2055 |

| Restrictions from family | 0.0111 | 0.2311 | 0.2055 |

| Restrictions from husband | 0.0223 | 0.0392 | 0.2051 |

| Managing family and business affairs | 0.0988 | -0.0691 | 0.1058 |

| Finding right organization to approach for assistance | 0.11 | -0.0963 | 0.0331 |

| Knowledge of suppliers | 0.1206 | -0.1656 | 0.0173 |

| Business communication skills | 0.1331 | -0.2791 | 0.0293 |

| Sales skills | 0.0602 | -0.2253 | -0.085 |

| Team building and maintaining | 0.061 | -0.206 | 0.2059 |

| Finding the right employees | 0.0552 | -0.1596 | 0.2106 |

| Knowledge of Governmental policies/procedures | 0.1001 | 0.0121 | -0.0036 |

| Knowledge of product launching | 0.1091 | 0.0749 | -0.0237 |

The start-up related challenges include lack of education; knowledge of Saudi labour law, government procedures and policies; launching the business; finding the right suppliers and organization for assistance; and developing communications skills. All these are relevant to start-ups and are common challenges for first-stage entrepreneurs and the need for the institutional level support is important. This also shows the lack of the contact between the institutional level stakeholders and the start-ups, as well as the lack of the necessary skills and knowledge possessed by the start-ups. This presents a huge opportunity for the organizations, such as incubators, universities, Chamber of Commerce and industry institutes to offer such training.

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Component Scores. Note, coefficients highlighted have a p-value<0.05.

Challenges Faced by Particular Businesses

In order to further investigate and understand the challenges being faced by the start-ups in more detail, the businesses were divided into eight main areas. The challenges shown separately regarding the different kinds of planning were grouped into one category, i.e., the business planning challenge. A bivariate correlation was carried out and challenges are correlated here separately (not factor wise).

These correlations provide factual results. The most difficulties are being faced by the 1) interior design, 2) women related, clothing and lingerie and 3) dentistry clinic businesses. These businesses are new and, therefore, the graduates who start their own business in these industries face numerous difficulties. The women in 1) beauty parlour, therapies and Spa, 2) children entertainment, and 3) education seem to have the least challenges, most likely due to the fact that these are relatively more traditional businesses (Table 8).

| Table 8 Correlations between Business Areas and Challenges |

||||||

| Knowledge of business planning | Knowledge of budgeting | Knowledge of HR issues | Knowledge of Saudi Labour Law | Knowledge of How to start business | ||

| Jewellery related | Pearson Correlation | 0.315** | 0.185* | -0.001 | 0.285* | 0.246** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.994 | 0.054 | 0.008 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Spa related | Pearson Correlation | .251** | .179** | 0.092 | 0.058 | .257* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.42 | 0.612 | 0.019 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Boutique including Abaya | Pearson Correlation | 0.266** | 0.097 | 0.173 | 0.009 | .219* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.008 | 0.394 | 0.128 | 0.936 | 0.037 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Food including restaurant and home | Pearson Correlation | -0.142 | -0.121 | -0.183 | -0.146 | -0.122 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.208 | 0.284 | 0.107 | 0.197 | 0.285 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Beauty related | Pearson Correlation | 0.023 | 0.294** | 0.173 | 0.009 | 0.103 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.838 | 0.004 | 0.128 | 0.936 | 0.367 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Event Planning | Pearson Correlation | 0.264** | 0.289* | -0.069 | 0.17 | 0.103 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.003 | 0.039 | 0.543 | 0.131 | 0.367 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Web Design and Computers | Pearson Correlation | 0.237* | 0.137 | 0.073 | -0.044 | 0.031 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.038 | 0.224 | 0.52 | 0.696 | 0.788 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

| Graphic Design & IT | Pearson Correlation | 0.285* | 0.279* | 0.247** | 0.310** | |

| 0.246 | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.103 | |

| N | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

| Restrictions from family | Restrictions from husband | Managing family and business affairs | Finding right organization to approach for assistance | Knowledge of suppliers | Business communication skills | ||

| Jewelry related | Pearson Correlation | -0.019 | 0.052 | 0.257** | 0.285** | -0.104 | 0.274* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.868 | 0.646 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.358 | 0.01 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Spa related | Pearson Correlation | 0.199 | 0.086 | 0.154 | 0.273** | -0.019 | 0.021 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.079 | 0.446 | 0.177 | 0.004 | 0.868 | 0.857 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Boutique including Abaya | Pearson Correlation | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.081 | -0.006 | 0.267* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.812 | 0.715 | 0.851 | 0.047 | 0.96 | 0.099 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Food including restaurant and home | Pearson Correlation | 0.235* | -0.157 | -0.162 | .281** | -0.126 | 0.251* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.097 | 0.164 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.264 | 0.029 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Beauty related | Pearson Correlation | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.081 | -0.006 | -0.002 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.812 | 0.715 | 0.851 | 0.473 | 0.96 | 0.987 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Event Planning | Pearson Correlation | 0.186 | 0.121 | .266* | .243* | 0.069 | -0.154 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.1 | 0.287 | 0.06 | 0.047 | 0.54 | 0.176 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Web Design and Computers | Pearson Correlation | -0.018 | 0.003 | 0.145 | 0.247* | 0.099 | 0.105 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.875 | 0.98 | 0.201 | 0.013 | 0.383 | 0.356 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

| Graphic Design & IT | Pearson Correlation | 0.229 | -0.198 | .285* | -0.264 | 0.279 | .263* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.304 | 0.079 | 0.03 | 0.402 | 0.201 | 0.014 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 79 | |

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

| Sales skills | Team building and maintaining | Finding the right employees | Knowledge of Government al policies/ pro cedures |

Knowledge of product launching | ||

| Jewelry related | Pearson Correlation | 0.063 | -0.059 | -0.059 | .197** | 0.065 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.584 | 0.604 | 0.605 | 0.007 | 0.57 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Spa related | Pearson Correlation | 0.054 | 0.071 | 0.142 | 0.035 | 0.188 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.64 | 0.532 | 0.209 | 0.761 | 0.094 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Boutique including Abaya | Pearson Correlation | 0.08 | 0.093 | -0.057 | -0.064 | -0.058 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.486 | 0.41 | 0.618 | 0.575 | 0.609 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Food including restaurant and home | Pearson Correlation | -0.203 | -0.178 | -0.157 | -0.13 | -0.118 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.073 | 0.114 | 0.163 | 0.251 | 0.295 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Pearson Correlation | 0.08 | 0.093 | -0.057 | -0.064 | -0.058 | |

| Beauty related | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.486 | 0.41 | 0.618 | 0.575 | 0.609 |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Event Planning | Pearson Correlation | 0 | -0.148 | -0.057 | .271* | .266* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 1 | 0.191 | 0.618 | 0.037 | 0.084 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Web Design and Computers | Pearson Correlation | 0.17 | 0.076 | 0.095 | 0.026 | 0.091 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.134 | 0.504 | 0.401 | 0.817 | 0.42 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Graphic Design & IT | Pearson Correlation | -0.284 | -0.26 | .255* | -0.256 | -0.243 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.301 | 0.702 | 0.031 | 0.22 | 0.12 | |

| N | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

The marketing, Operations, Strategic and financial planning are put together for analysis. The majority of the female start-ups seem to have issues with planning, knowledge of Saudi labour law, team building and governmental policies. These skills are not taught at most colleges and universities. Many start-ups also do not know the governmental procedures and policies, causing delays in obtaining their licenses. This can result in unnecessary interruption, suspension, or temporary lapses in the start-ups, as much of the work is done by expatriates. Obtaining visas and finding immigrant workers are already an issue and a lack of knowledge of law and polices aggravates the situation.

Females commencing and establishing a start-up in a social arena face the least difficulty, which is based on the fact that such projects are generally initiated by women belonging to wealthier families, who have established reputations and credentials. We have numerous examples of philanthropic and social enterprises being started by the women of leading business families in Saudi Arabia.

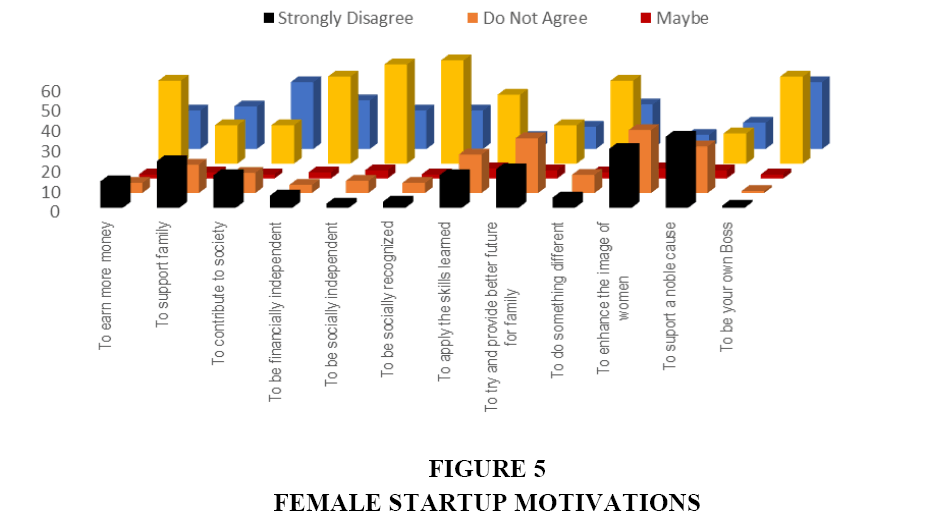

Female Start-Up Motivations

The findings as shown in Figure 5 somewhat support the work of Robinson (2001), Dhaliwal (1998), Orhan and Scott (2001), Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) and Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005), regarding the push and pull factors of motivation. However, the study refutes the narrative of Wennekers et al. (2001).

The push and pull factors for female start-ups vary a bit from what literature suggests as a general factor. The Saudi females seem to be more pulled than pushed in start-ups. As the society is becoming more and more liberal, female start-ups commence their venture to seek more social independence, recognition, enhance image and become her own boss. The circumstances also have been pushing them to support their families, as they are largely motivated by ‘wanting to earn more money’ and be ‘financially independent,’ perhaps influenced by the recent downturn in the Saudi economy. Women start-ups are equally divided over their desire to contribute positively to society.

Motivation Antecedents

Table 9 shows the motivations by motherhood category (yes, no) and reveals interesting results. Being a mother seems to affect the family thought on the female start-ups in motivating them ‘to try to provide a better future for their families’ and ‘to be their own boss’.

| Table 9 Motivations Means of Business Women Who are Mothers |

||||||

| To earn more money | To support family | To contribute to society | To be financially independent | To be socially independent | To be socially recognized | |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| Mother | 4.53 | 1.63 | 2.96 | 3.55 | 4.39 | 5.61 |

| Not Mother | 3.96 | 2.14 | 2.68 | 2.61 | 3.54 | 4.54 |

| To apply the skills learned | To try and provide better future for family | To do something different | To enhance the image of women | To support a noble cause | To be your own Boss | |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| Mother | 7.27 | 8.47 | 7.94 | 8.75 | 9.73 | 10.12 |

| Not Mother | 5.5 | 6.07 | 6.07 | 6.64 | 7.32 | 7.43 |

Similarly, they are more concerned with enhancing the image of women, to be socially recognized and apply the skills they learned. This is an exciting development in a society such as Saudi Arabia and can imply the ‘breaking of shackles.’ The non-mother females also desire to do something different and enhance the image of women.

A notable number of responses suggest that start-ups are purely commercial based and not created to support noble causes. It is mostly pull factors that help them to attempt to establish a start-up. A notable number of responses did not start their business to support their family.

The correlations between ‘being a mother’ and motivations to start an enterprise reveal some interesting information, as shown in Table 10. It shows that intrinsic motivations are ‘to earn more money,’ ‘to support their family,’ and ‘to provide a better future for their family.’ This shows that the female start-ups are now willing to take an active role in society and be productive both in the family and economy.

| Table 10 Relationship Between Motherhood and Motivations |

||||||

| To earn more money | To support family | To contribute to society | To be financially independent | To be socially independent | To be socially | |

| Being Mother | 0.103* | 0.162* | -0.015 | -0.145 | -0.112 | -0.107 |

| 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.895 | 0.2 | 0.324 | 0.346 | |

| 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| To apply the skills learned | To try and provide better future for family | To do something different | To enhance the image of women | To support a noble cause | To be your own Boss | |

| Being Mother | -0.17 | .229** | -0.184 | -0.196 | -0.2 | -0.212 |

| 0.131 | 0 | 0.102 | 0.082 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

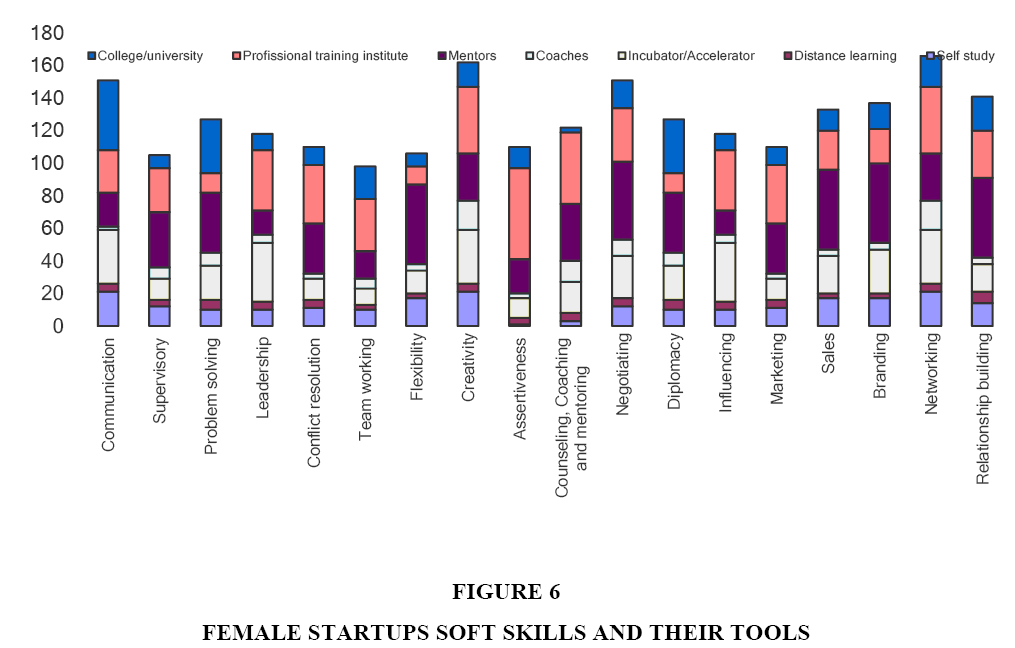

Soft Skills and Tools Required

The literature identifies a number of soft skills required by first-stage entrepreneurs to successfully commence a start-up. Acknowledging the literature findings and seeking validation, a more relevant and newer question was asked, i.e. how can these skills be provided? What tools are more appropriate and how can these skills is acquired? The responses are shown in Figure 6.

The role of professional training institutes, mentors and incubators tops the other modes of skills development. The role of universities follows these top three. It has been pointed out by the respondents that the soft skills incubators can help build are creativity, influencing, communications, leadership, negotiations and problem solving skills. Whereas, the mentors can successfully help the start-ups develop their relationship building, branding, marketing, diplomacy, negotiations, flexibility, conflict resolution and problem solving skills. Similarly, the female start-ups seem to opine that professional training institutes can polish their leadership, conflict resolution, assertiveness, counselling, influencing and relationship building skills. This supports the older studies and justifies the work of Khan (2013).

Conclusion

Referring to the questions raised at the end of the literature review, it can be concluded that the role of society, including family and husband has changed tremendously. The women are now more dynamically meeting the challenges and ecosystem is assisting in several ways. The motivational factors are not limited to a few, there is a good mix of push and pull factors. These are now discussed in more detail in the paragraphs below.

It was witnessed in the literature review that there is a lack of evidence on female startups in general and for Saudi Arabian start-ups in particular. This research hopes to open the doors for further research and enhance our understanding of the deficiencies and efficiencies in the entrepreneurship ecosystem for women start-ups in Saudi Arabia.

The findings above have contributed both to our knowledge of female entrepreneurs in the Arab region and globally, however, there are some unique findings owing to different cultures and norms in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Arabian female start-up motivations and challenges emanate from their traditional culture, which as Afaf et al. (2014) states “is a masculine society…strongly affected by cultural traditions and religion. The separation of the genders is obligatory in Saudi cultures and societal norms impact on all sides of life”.

However, this study may hint that shackles on women empowerment are being broken and that societal taboos and restrictions are under transition to a society and cultural of adaptability. There are numerous indicators for optimism for the women start-ups alongside the risks. The Literature pointed out that in the Arab countries women participation in the labor force is influenced by culture and shaped by the Islamic principles. The Dechant and Al-Lamky (2005) study pointed to some cultural practices that might prevent women from conducting their business as compared to men.

This study again provides an updated view that the society is more accommodating and supportive of female entrepreneurship. The role of family, husband and the society in general has been seen as a positive factor in contributing to female start-ups in Saudi Arabia. Similarly, it has been revealed that motherhood and economic conditions also affect the choice of females to commence a commercial venture.

Similarly, the motivational factors provide a stark contrast between Saudi female start-ups and elsewhere. Prior studies have asserted that in general women join the work force out of the need for achievement and desire for respect. However, in Saudi Arabia, in addition to independence and recognition, we also witnessed the economic reasons (push factors) to start a business.

Our findings on the challenges being faced by female start-ups are in contrast to those found by Nilufer (2001), Carswell and Rolland (2004) and Salehi-Isfahani (2000). Their findings were different than what we found in Saudi Arabia. Start-up related challenges are quite significant in Saudi Arabia, as compared to the developed and industrialized countries, where an ecosystem is more evolved. This highlights the need to further strengthen the ecosystem’s institutional stakeholders so that they can enable enterprise.

Society and team related challenges are not highlighted significantly in the literature. The challenges envisaged by Ram (1996) and Ozgen and Ufuk (1998) determined some basic values and properties, whereas, this study points out specific challenges. We also show that the culture is evolving. The families and husbands are more cooperative and Saudi society is generally more accepting of women in business. However, a lack of business development and related support from the spouse continues to be evident.

Recommendations

The perceived deficiency in governmental support is clear from our findings. Many challenges can be eradicated with effective legislation and creation of enablers in the institutional and strategic levels of entrepreneurship ecosystem of Saudi Arabia as noted by Rahatullah (2016). For example, government can help train female entrepreneurs if they want to have a more profound impact on improving and modernizing their economy. There is a need to have women-specific legislation to ease the burden on female start-ups and to help them set up and manage their businesses effectively and efficiently.

Building on the work of Rahatullah (2016), who mapped the existing entrepreneurship ecosystem of Saudi Arabia and then the evolution of the ecosystem, this study acts as a catalyst highlighting opportunities for potential institutional stakeholders. Aspiring entrepreneurs must be able to exploit the services like training and development, coaching and mentoring organizations and freelancers. There is a clear need for lobbying professionals and firms to establish workshops, training and other forms of assistance for female start-ups. The universities and institutions need to create courses in soft skills, project management, operations, basic finance, accounting, communications and branding. These organizations can also hold workshops and seminars for female start-ups on understanding the legal framework of the Kingdom and communicate any legal assistance that is available. Our study sheds light on the need for making the venture funding procedures simpler for the female start-ups knowing that they are taking initiatives and need support from key strategic and institutional stakeholders. Crowd funding platforms could be an ideal forum for the venture funding and these platforms could take the shape of equity and philanthropic types.

Finally, we recommend a future comprehensive study on the risks associated with business failure. By identifying these risks and causes of failure, we can begin to identify feasible solutions to support more women start-ups in Saudi Arabia in particular and in the Middle East in general. Since business failure is viewed differently in the Middle East, although it is a relatively common part of starting entrepreneurial ventures, we believe it is critical that the business community and government organizations collaborate to support businesses before they fail – and to provide safety nets for after businesses fail.

Limitations

Like every research this study also faced difficulties as enumerated hereunder.

1. It had been extremely difficult and time consuming to identify and reach out to the female start-ups. Even though, these women are in business majority of them took their time to respond to the questionnaires. It requires help from locals, local chambers of commerce and friends and families, networks, universities and colleges in the areas.

2. The study benefits only from the sectors reported; perhaps more business sectors can be added.

References

- Afaf, A., Cristea, A.I. & Al-Zaidi. M.S., (2014). Saudi Arabian cultural factors and personalized e-learning. Edulearn14 Proceedings, 7114-7121.

- Rahatullah, M.K. (2014). Financial synergy in mergers and acquisitions. The IEB International Journal of Finance, 2-19.

- Aldrich, H., Aldrich. R. & Langton. N. (1998). Passing on privilege. Research in Social Stratification, 17, 291-317.

- Al-Lamky, A. (2005). Towards an understanding of Arab women entrepreneurs in Bahrain & Oman. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 10(2).

- Amstrong, J. (2001). In Kogan. Human Resources Management Practice (8th Ed 2001).

- Assaad, R. & El-Hamidi, F. (2002). Population challenges in the Middle East and North Africa: Towards the 21st century, Erf, Cairo. Female labor supply in Egypt: Participation and hours of work in Sirageldin (First Edition).

- Baker, T. (2005). A framework for comparing entrepreneurship processes across nations. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(5), 492-504.

- Carswell, P. & Rolland, D. (2004). The role of religion in entrepreneurship participation and perception. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 1(4), 280-6.

- Carter, S., Anderson, S. & Shaw, E. (2001). Small business service. Women's business ownership: a review of the academic, popular and internet literature.

- Coleman, S. (2002). Constraints faced by women small business owners: Evidence from the data. Journal of Development Entrepreneurship, 7(2), 151-74.

- Cornwall, J. (1998). The entrepreneur as a building block for community. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 3(2), 141-148.

- Costanza, G., Hrund, G. & Angela, M. (2003). Statistical division Unece Geneva. The Status of Statistics on Women and Men's Entrepreneurship in the Unece Region.

- De Groot, T.U. (2001). Women entrepreneurship development in selected African countries UNIDO, Vienna.

- Dechant, K. & Al-Lamky, A. (2005). Towards an understanding of Arab women entrepreneurs in Bahrain & Oman. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 10(2).

- Dhaliwal, S. (1998). Silent contributors: Asian female entrepreneurs and women in business. Women's Studies International Forum, 21(5), 463-74.

- Dunkelberg, W. (1995). Presidential address: small business and the U.S. Economy. Business Economics, 30(1), 13-18.

- Dyer, B. & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2008). Apparel import intermediaries' secrets to success: Redefining success in a hyper-dynamic environment. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 12(1), 51-67.

- Elaine, L.E. (2002). What makes for effective microenterprise training? Journal of Microfinance / ESR Review, 4(1).

- Elisabeth, S.C. & Berger, A.K. (2016). Female entrepreneurship in startup ecosystems worldwide. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5163-5168.

- Fagenson, E. (1993). Personal value systems of men and women entrepreneurs versus managers. Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 409-30.

- Fergany, N. (2002). Arab human development report: Creating opportunities for future generations, United Nations Development Program. Regional Bureau for Arab States.

- Frost, R. (2013). Applied kinesiology: A training manual and reference book of basic principles and practices. North Atlantic Books.

- Ennari, E. & Lotti, F. (2013). Female entrepreneurship and government policy evaluating the impact of subsidies. Firms' Survival. Bank of Italy Occasional, Paper No. 192. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2303710 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2303710

- Hatun, U. & Ozgen, O. (2001). Interaction between the business and family lives of women entrepreneurs in Turkey. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 95-106.

- Heltzell, D. (2015). Capsalis, Retzloff Advising Natural Foods Startups. BizWest, 34(16), 22. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1704442843?accountid=130572

- Hoffman, K., Parejo, M. & Bessant, J. (1998). Small firms, R&D, technology and innovation in the UK. A Literature review Technovation, 18(1), 39-55.

- Kaiser, U. & Müller, B. (2015). Skill heterogeneity in startups and its development over time. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 787-804.

- Karim, N.A. (2000). Factors affecting women entrepreneurs in small and cottage industries in Bangladesh. Gender and Small Enterprises in Bangladesh.

- Lilia, L. (2014). Political, aesthetic and ethical positions of Tunisian women artists. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(2).

- Mark, W., Dickson, P. & Wake, F. (2006). Entrepreneurship and education: What is known and not known about the links between education and entrepreneurial activity. The Small Business Economy for Data Year 2005, 84-113.

- Maula, M., Erkko, A. & Pia A. (2005). What drives micro-angel investments? Small Business Economics, 25(5), 459-475.

- Minniti, M. (2010). Female entrepreneurship and economic activities. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 294-312.

- Khan, M.R. (2013). Mapping entrepreneurship ecosystem of Saudi Arabia. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, 9(1).

- Naser, K., Mohammed, W.R. & Nuseibeh, R. (2009). Factors that affect women entrepreneurs: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 17(3), 225-247.

- Ngozi, G. (2002). Women entrepreneurship and development the gendering of microfinance in Nigeria. 8th International Interdisciplinary Congress on Women, 21-26.

- Nilufer, A. (2001). Jobs gender and small enterprises in Bangladesh factors affecting women entrepreneurs in small and cottage industries in Bangladesh. SEED Working Paper No. 14.

- Nuñez, E. (2015). The temporal dynamics of firm emergence by team composition examining top-performing solo. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 20(2), 65-92.

- Orhan, M. & Scott, D. (2001). Why women enter into entrepreneurship an explanatory model. Women in Management Review, 16(5), 232-43.

- Rahatullah, M.K. (2016). Entrepreneurship ecosystem evolution strategy of Saudi Arabia. Advancing Research in Entrepreneurship in Global Context, 7-8.

- Ram, D.L. (1996). Women Entrepreneurs, (A.PH. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi).

- Rice, G. (2004). Doing business in Saudi Arabia. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46(1), 59-84.

- Riley, S. (2006). Mentors teach skills, hard and soft. Electronic Engineering Times, 1-1, 14.

- Robb, S. (2002). Entrepreneurial performance by women and minorities: The case of new firms. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(4), 383-97.

- Robinson, S. (2001). An examination of entrepreneurial motives and their influence on the way rural women small business owners manage their employees. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 6(2), 151-67.

- Salehi-Isfahani, D. (2000). Microeconomics of growth in Mena - The role of households. Global Development Network.

- Shah, N. & Al-Qudsi, S. (1990). Female work roles in traditional oil economy: Kuwait. Research in Human Capital and Development, 6, 213-46.

- Norean, R. & Christopher M. (2016). Entrepreneurship and Innovation in the Middle East: Current challenges and recommended policies. Innovation in Emerging Markets, 87-101.

- Sonmez, J.Z. (2015). Soft skills the software developer's life manual. Manning Publications.

- Stuart, R., (2013). Essentials of human resource training and development.

- Thurik, R. & Wennekers, S. (2004). Entrepreneurship small business and economic growth. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 11(1), 140-149.

- Wennekers, S., Noorderhaven, N., Hofstede, G. & Thurik, R. (2001). Cultural and economic determinants of business ownership across countries. Babson College, Babson, MA, Available at: http://www.babson.edu/entrep/fer/Babson2001/V/VA/VA/v-a.htm

- Zedtwitz, M. (2003). Classification and management of incubators: Aligning strategic objectives and competitive scope for new business facilitation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 3(1), 176-196

- Zewde & Associates. (2002). Jobs gender and small enterprise in Africa: The study of women's entrepreneurship development in Ethiopia. National Conference on Women's Entrepreneurship Development in Ethiopia.