Research Article: 2017 Vol: 20 Issue: 2

Risk of Intellectual Property Among Fashion Designs

Narumon Saardchom, NIDA Business School

Abstract

Fashion design has faced uncertainty within intellectual property laws in most countries. Generally, it could be treated differently by numerous laws, mainly copyright, trademark, trade dress and patent design. Fashion design disputes tend to be more perplexing while courts in different jurisdictions have struggled with the analysis of fashion design claims in various ways. This article examines several famous fashion design cases in the U.S. The facts and proceedings of copyright lawsuits in Thailand are compared to reveal an interestingly unclear borderline of protection that put all related parties in fashion industry at risk. The article aims to (1) define a legal framework of fashion design, (2) discuss facts and proceedings related to fashion design lawsuits in the U.S. and Thailand and compare court decisions and (3) analyse potential risk for fashion designers and fashion industry.

Keywords

Fashion Design, Copyright, Design Patent, Trademark, Confusion, Creativity, Infringement, Legal Risk.

Introduction

The protection of fashion design is not well defined under legal regulations in most jurisdictions. In general, fashion design is not clearly defined in any specific law and its protection is likely to expand through various intellectual property laws; generally copyright, trademark and design patent. Moreover, its practical applications in many jurisdictions have often been perplexing and unclear.

Legal scholars have different views. On the one hand, some scholars criticize the available legal regime for failing to protect fashion design; arguing that the court should expand more protections and Congress should fix the problem. On the other hand, the other group of legal scholars propose “piracy paradox” explanation; arguing that the fashion industry counter-intuitively operates within a low intellectual property equilibrium in which copying does not really deter innovation and may actually promote it.

Likewise, courts in different jurisdictions have struggled with various approaches of analysis and reasoning. Accordingly, fashion design could be treated differently by several intellectual property laws and varied interpretations. Such unclearness causes major legal risk in design industry worldwide. This article studies intellectual property protection in fashion design and discusses court cases as well as proceeding related to fashion design lawsuits in the US and Thailand. Recently, the US Supreme Court formulated a two-prong test in Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands, 578 US (2016) to focus on whether the design element can be identified separately from the article and whether the design element is imagined separately from the useful article. However, the Court was careful to note that even if respondents ultimately succeed in establishing a valid copyright protection, respondents could not bar any person from manufacturing uniforms with identical shapes, cuts and dimensions as the ones in question. In addition, the Court declined to rule on whether the surface decorations in question were sufficiently qualified for copyright protection by holding that “we do not today hold that the surface decoration is copyrightable. We express no opinion on whether these works are sufficiently original to qualify for copyright protection”. Still, this holding leaves significant uncertainty about the application of copyrights to surface decoration and fashion design.

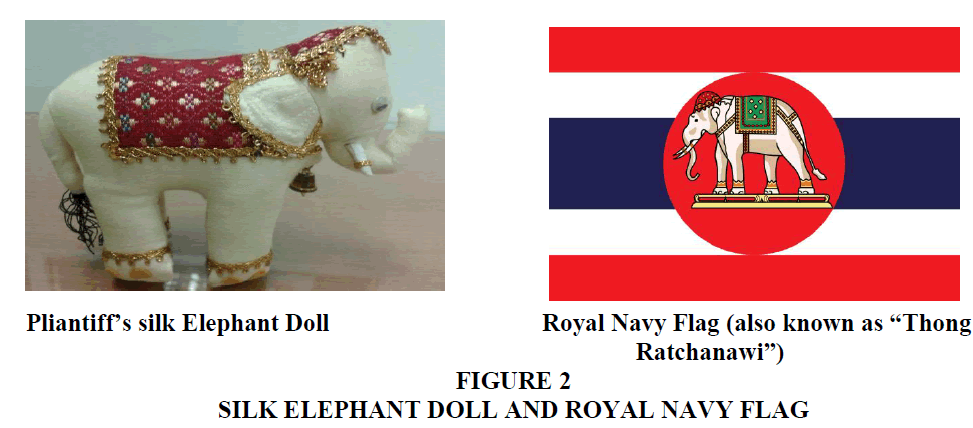

In a similar fact, the Thai Supreme Court held in the case number 19305/2555 (2012), that copyright ability needed to meet the requisite level of creativity. Designing silk elephant doll similar to the design of elephant emblem on the Royal Navy flag was not qualified as the creativity level and not copyrightable. The justification for copyright protection in this case establishes high standard for a designer to claim his or her copyright.

This article examines various intellectual property protections of fashion design; particularly trademark, design patent and copyright. Then, the protection of fashion design in the U.S. is observed by focusing on copyright law and the U.S. Supreme Court decision. This article further analyzes the recent Supreme Court decision of Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc. case, as well as the famous Supreme Court decision on the standard of copyright ability-Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co. Next, this article inspects intellectual property protection of fashion design in Thailand and analyzes two Supreme Court judgments-the silk elephant doll case and the bas-relief (basso-rilievo) of Apsara case. The last part of this article analyses potential consequences on design industry and proposes certain observations.

Intellectual Property Protection of Fashion Design

Theoretically, fashion design can be protected under many intellectual property laws; particularly trademark, design patent and copyright. Generally, trademark protects name or symbol that identifies the source of goods or services. Patent design protects ornamental design of a functional item or product. Copyright protects various forms of expression, possibly including design of article. However, these laws are basically overlapping when applied for fashion design protection.

Trademark covers a word, phrase, symbol, and/or design that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others. For example, “Adidas” identifies shoes made by Adidas and distinguishes them from shoes made by other shoe companies. Unlike copyright or patent, trademark rights can last forever through registration by filing specific documents and paying fees at regular intervals. The trademark owners hold right not only in the markets where their brands first acquired fame, but also in other markets; for instance, Porsche AG licensing its name for the manufacture of sunglasses and Coca-Cola Company licensing “Coca-Cola” T-shirts.

Patent in most countries, including US and Thailand, widens its scope to cover various categories. Patent originally is an exclusive right granted for an invention which is a product or a process that normally provides a new way of doing something or offers a new technical solution to a problem. However, design patent which is based on decorative, non-functional features, is the most related to fashion design. The patent owner has the exclusive right to license other parties to use the invention or design. The exclusive right ends after a patent period which is usually 10 to 15 years for a design patent and 20 years for patent of invention.

Copyright protects virtually all forms of expression; for example, novels, motion pictures, music, videos, videogames, map photograph and computer program. Since copyright protects expression, fashion design can easily be expressed in some medium and protected as copyright work. The copyright owner has the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, perform, display, license and to prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work.

Intellectual Property Protection of Fashion Design in the US

Although fashion design in the US can be protected through trademark, design patent and copyright, each type of protection has its own difficulties. Trademark fundamentally prohibits copying of logos, symbol and brand names of cloth manufacturer, not the design and not for designers. Design patent seems to be a rational alternative for fashion design since it is based on decorative, non-functional features. However, it is hard for the designers to prove the newness for their designs because they are often based on the previous designs of their own work or the work of others. In addition, design patent does not cover features of clothing that are solely for function since the design patent is aimed to protect design or ornamentation. Thus, design patent is likely to provide a limited protection to most clothing design.

Clothing design does not fit well under copyright law. The Copyright Act of 1976, section 102(a)(5) provide protection of “pictorial, graphic and sculptural works” and section 101 defines that “pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features” of the “design of a useful article” are eligible for copyright protection as artistic works if those features “can be identified separately from and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” This protection is aimed directly to the textile print or unique flourish of clothing but does not give the copyright over the design of clothing to the designer.

Fashion design protection should not be taken lightly given that fact that it is now a major industry with global annual sales larger than the sum of books, movies and music industries. Moreover, fashion business has been rapidly growing, particularly in the last few decades. However, there are very few opinions by the US Supreme Court clarifying whether fashion design should be protected in any category of intellectual property laws; and if so, to what extent. Copyright protection for fashion design has been limited, generally due to clothing designs are utilitarian function or “useful articles” under section 102(a)(5) of the Copyright Act. There are different tests developed by some US court of appeals for determining separability of the protected parts and unprotected part. Recently, the US Supreme Court finally decided on the issue of copyright separability in Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc.

Under the Copyright Act, section 102(a)(5), “useful articles” are not protected, but pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features of the design of a useful article are eligible for copyright protection if those features can be identified “separately from,” and are capable of “existing independently of,” the utilitarian aspects of the article.” Although the statutory context seems to be clear, application of this “separability standard” has been problematic and unpredictable.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court decided the case, most designers and fashion industries believed that the Court would expand copyright protection to cover useful articles, such as clothing, computer game and furniture. It was also thought that this holding would bring a certain degree of harmony among many practical considerations of various appeal courts and provide some refined predictability for the copyright infringement disputes.

Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands Inc.

While the separability standard under the copyright protection for fashion design has been variable, new complicated disputes produce even more difficulties. On March 22, 2017, in a highly anticipated decision, the US Supreme Court issued its opinion in Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc.,580 US (2017), holding a two-part test to determine when design elements incorporated into a useful article may be eligible for copyright protection. The Court held that “a feature incorporated into the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection only if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work-either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression-if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated”.

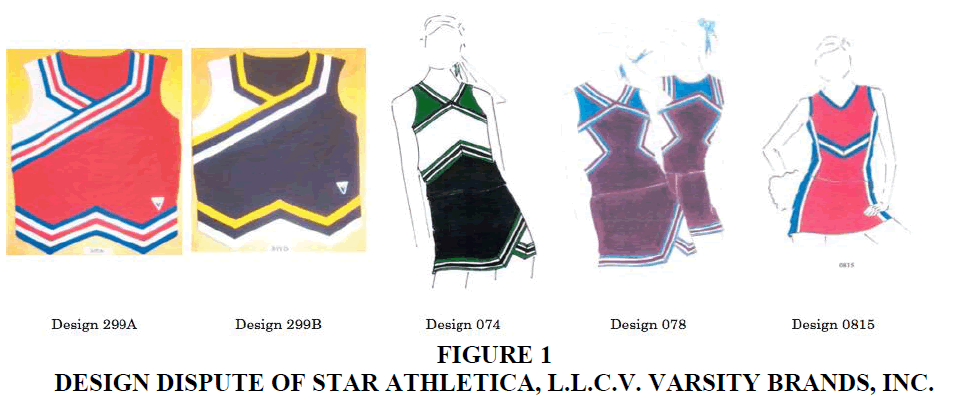

In this case, Varsity Brands, Inc. (Varsity) owned over 200 copyright registrations for its designs of cheerleader uniforms, for example, lines, chevrons, colourful shapes. Star Athletica, L.L.C. (Star) started its cheerleading uniform business and was sued by Varsity for copyright infringement of the following 5 designs shown in Figure 1:

The District Court held that Varsity’s designs were not eligible for copyright protection. It reasoned that those designs could not be physically or conceptually separated from protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works because they served the utilitarian or useful function and therefore could not be physically or conceptually separated from their utilitarian purpose of identifying the garments as cheerleading uniforms. However, the Appeal Court reversed and held that the “graphic designs” were capable of existing independently from the utilitarian uniforms because those designs could be incorporated onto the surface of different types of garments, or hung on the wall and frame as art.

The Supreme Court, in a 6-2 decision, rejected many physical and conceptual separability standards from federal appeal courts and based the Court’s new test on the requirement articulated in Section 101 of the Copyright Act. Firstly, the statutory language “can be identified separately from” was interpreted by the Supreme Court as “can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article.” Secondly, the statutory language “and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article” was translated by the Supreme Court as “and would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work-either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression-if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated”.

In its decision, the Supreme Court stated a two-part test for separability standard, but neither decide whether fashion patterns or motifs overall (in this case, the lines, chevrons and colourful shapes appearing on cheerleading uniforms) were eligible for protection, nor decided whether the specific design elements involved in the case were sufficiently original to qualify for protections. Such a decision raises numerous interesting questions.

The Supreme Court even further concludes that “our test does not render the shape, cut and physical dimensions of the cheerleading uniforms eligible for copyright protection”. While this decision reaffirms that two- or three-dimensional artwork can be protected as artwork when it is placed upon clothing, there still remains unclear copyright protection for such useful article. At present, we can only conclude that this Supreme Court decision simply clarifies statutory language for lower courts to interpret the law. Accordingly, the actual impact and enforcement of design protection within the apparel industry will depend on the interpretation of lower courts.

Interestedly, Justice Breyer and Justice Kennedy guide in the dissenting opinion that the designs that Varsity submitted to the Copyright Office in this case are not eligible for copyright protection since the relevant design features are replicate the underlying useful article of which they are a part. “Hence the designs features that Varsity seeks to protect are not “capable of existing independently of the utilitarian aspects of the article”. In other words, Justice Breyer and Justice Kennedy opine that the design features in Varsity’s pictures cannot exist separately from the utilitarian aspects of the dress.

Notably, a very famous Supreme Court decision on the standard of copyright ability-Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 US 340 (1991) could be added for future interpretation. In Feist Publications, Inc., the Supreme Court held that information alone without a minimum of original creativity cannot be protected by copyright. The Court then clarified that the standard for creativity is extremely low. It needs not be novel; rather it only needs to possess a "spark" or "minimal degree" of creativity to be protected by copyright. However, the raw data or information itself alone (in this case was the collection of names, streets and phone numbers in a telephone directory) is not copyrightable.

Therefore, it is likely that the lower courts will apply the standard of copyright ability in Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co. with the two-part separability test in Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc.

Intellectual Property Protection of Fashion Design in Thailand

Similar to laws in the US, fashion design in Thailand can be protected under different intellectual property laws; particularly trademark, design patents and copyright.

Thai Trademark Act B.E.2534 (1991) protects mark used with fashion design product and prohibits the uses of identical mark or similar mark that the public might be confused or misled as to the owner or origin of the product. However, trademark law does not protect the design of the product itself.

The Patent Act B.E.2522 (1979) includes 3 types of patents in the same act which are patent, design patent and petty patent. Design patent protects “any form or composition of lines or colours which gives a special appearance to a product and can serve as a pattern for a product of industry or handicraft,” while patent and petty patent focus on new invention. Under article 56, the design has to be “new” from known or used design to be eligible for protection. Until 2017, there has been no single Supreme Court case on fashion design in Thailand, but it does not mean that fashion industry in Thailand does not face with a problem with fashion design protection. Nevertheless, there are Supreme Court decisions on related design cases that can shed light on potential legal risk for fashion designers and fashion industry in Thailand.

In the Supreme Court decision number 12602/2555 (2012), the Court held that the inventive step is not the requirement of design patents registration. The only requirement is the newness of design for industry under article 56. In this case, the defendant designed lamp used for aquarium fish and later registered his lamp design in 2001 (design patents number 17496) before distributed the aquarium lamp to the market. The plaintiff, another distributor, filed the lawsuit to cancel such design patent on the ground that the design was too simple and similar to the plaintiff’s aquarium lamp. The Supreme Court clarified that the design patent did not need “inventive step” requirement in patent for invention as the plaintiff claimed. Design patent only need the newness of design under article 56 of the Patent Act B.E.2522 (1979). In this case, the defendant designed lamp used for aquarium fish and included lamp stand and reflexing pad to the lamp. The design was different from previously similar product and was eligible for the design patents.

This holding ensures the broaden scope of design patent under the Patent Act and can be applied to protect fashion designs those are qualified “new.” Nevertheless, patent law protects only particular designs which are registered under the Patent Act. Designers accordingly need to properly register his or her specific works. In practices, design patent might not fit the needs of the designers and fashion industries as it is costly and time consuming. The Department of Intellectual Property of Thailand describes the complicated processes to receive a design registration that usually needs more than 1 year. Such procedures include filing, investigation processes and publication period and opposition period. Consequently; difficulties of the design patent registration practically deter effective protection of fashion design. Under the fast moving fashion trend, the patent protection would become commercially useless by the time the patent was granted.

Copyright offers more practical advantages compare to trademark and design patents. On the one hand, the “artistic work" under Article 4 of the Copyright Act B.E.2537 (1994) provides broader language to easily cover fashion design. The most benefit of copyright protection is its automatic protection as soon as the work comes into existence and it remains protected during the lifetime of the author (copyright creator) plus 50 years which is much longer than the 10 years period of design patent. On the other hand, the extensive meaning of “artistic work” causes more uncertainty and largely depends on the interpretation by the courts.

In the Supreme Court decision number 19305/2555 (2012), the Court held that in order to be eligible for copyright protection, the copyright creator needed to utilize enough effort to create his or her work and such work should be originated by such author, not be copied, reproduce, or adapt from other copyrighted work.

In this case, the copyright creator designed and produced miniature silk elephant doll. The doll had become popular as popular souvenir among tourists. Shortly after, the defendant made and distributed very similar silk elephant doll. The plaintiff then sued the defendant for copyright infringement. In its decision, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiff’s elephant doll was not eligible for copyright.

The Supreme Court compared the plaintiff’s elephant doll to the Royal Navy flag (also known as “Thong Ratchanawi”) with a white elephant in regalia centred on the national flag shown in Figure 2. Then, the Supreme Court reasoned that the designs of elephant in regalia of both works were similar and concluded that the plaintiff copied the elephant from the Royal Navy flag with only insignificant changes. The design did not show that the plaintiff put enough effort in such design in order to claim copyright. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the plaintiff was not the “author” under the Copyright Act and therefore no infringement existed.

Notably, the Supreme Court decision number 7121/2552 (2009) also declined the copyright of the bas-relief (basso-rilievo) of an Apsara (also known as “Tep Apsar”) by similar reasoning. In this case, the Supreme Court held that the sculptor of the bas-relief of an Apsara was not eligible for copyright because the sculptor copied the design from the previous Thai and Khmer sculptures with insignificant changes. Accordingly, the plaintiff (sculptor) could not show that he utilized enough effort to create such bas-relief and such work was not eligible for copyrighted work. Although the reproduction or adaptation of such bas-relief showed certain level of industriousness, the Court considered that it was not reach the level of copyright ability under the Copyright Act.

Thai Supreme Court establishes standard of copyright ability which requires the author’s effort to meet the level of creativity. The interpretation of “effort” by the Supreme Court is rather demanding. The miniature elephant doll case and the bas-relief sculptor case are good examples. Although the plaintiff in the miniature elephant doll case has ever seen the Royal Navy before, he creates his elephant entirely different from that on the flag. Major differences include shape and major parts of elephant, colour and design of clothes on elephant back, movement and character. Designing and creating such original doll show a certain level of creativity. However, such creativity is not enough for the level of “enough effort” under the Thai Supreme Court interpretation. Similarly, designing and creating the bas-relief sculptor of Apsara which utilizes more technique and skill also could not pass the same level of “enough effort.”

Compare to the standard established in Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co., the US Supreme Court views that “to be sure, the requisite level of creativity is extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice”. Justice O’Connor further holds that originality does not signify novelty, a work may be original even though it closely resembles other works, so long as the similarity is fortuitous, not the result of copying. For example, two poets, each ignorant of the other, compose identical poems. Neither work is novel, yet both are original and, hence, copyrightable. It seems that creating whole elephant doll or bas-relief sculptor is fulfilled the level of creativity in Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co.

Applying high standard of copyright ability under Thai Supreme Court cases could burden and curtail copyrightable work in Thailand and cause serious legal risk to future creativity. Moreover, it is almost not possible to create a work that is totally new and not related to any previous work.

Analysis and Conclusion

Fashion law commonly involves various intellectual property rights, including trademark, design patent and copyright. However, fashion design could not particularly fit to any legal regulations and causes uncertainties for fashion industry. The need to gain well-defined protection is increased since fashion industry has become an important part of the global economy. This paper analysed and proposed three observations to properly manage intellectual property risks faced by fashion designers and fashion industry.

First, copyright regulations generally provide practical advantages to protect fashion designs-broad language, automatic protection; protection period is much longer than other intellectual property rights. Nonetheless, courts in different jurisdictions may apply and interpret their copyright laws differently.

Second, well-defined language of copyright law will provide better protection and reduce legal risk. Fashion design usually represents natural beauty to clothing, as well as embodies creative design and the relation of that work to others, past and present. Accordingly, fashion designs commonly share some similarities. Given wide-ranging of fashion design infringements which vary from exact copy of design, close copying, knock off, to remixing, it is necessary to consider the scope of copyright protection needed for such certain potential infringements. The suitable protection should be clearly defined in the copyright law.

Finally, the state of law with respect to the fashion industry is changing with fast pace. There have been new disputes and new case laws over the past decade. The variable interpretation and reasoning in various jurisdictions can hinder the proper protection and cause uncertainties to the fashion industry.

In Star Athletica, L.L.C. Varsity Brands, Inc., the US Supreme Court explains statutory language and provides guidance to lower courts on deciding if cheerleading pattern should be protected. Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co. clarifies that the requisite level of creativity is extremely low, even a slight amount will suffice. It seems that the U.S. courts have more room to apply proper level of protection to design work. Thai Supreme Court, on the contrary, sets high standard of creativity in the miniature elephant doll case and the bas-relief sculptor case as mentioned. Such differences cause risk to fashion design and industry, particularly global brand’s product. Legal risks, arisen from intellectual property law for fashion design, should be mitigated through harmonized proper understanding of copyright law among fashion designers, fashion industries and most importantly among the courts.

EndNotes

1. See Karina K Terakura, Comment, Insufficiency of Trade Dress Protection: Lack of Guidance for Trade Dress Infringement Litigation in the Fashion Design Industry, 22 U. Haws. L. Rev. 569, 619 (2000). This article argues to expand protection for fashion designs and “[c]ourt need to adequately safeguard innovation and creativity in the fashion business.” Also, several articles criticize Congress to fix and provide more legal protection. Also see Anne Theodore Briggs, Hung Out to Dry: Clothing Design Protection Pitfalls in United State Law, 24 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 169,194, 213 (2002)

2. See Kal Raustiala & Christopher Sprigman, The Piracy Paradox: Innovation and Intellectual Property in Fashion Design, Virginia Law Review, Vol. 92, p. 1687, 1691-1692 (2006). In addition, curtain scholar argues that fashion has functional nature for human, intellectual property protection therefore should be clear-cut and well-defined. See Buccafusco, Christopher and Fromer, Jeanne C., Fashion's Function in Intellectual Property Law (August 18, 2016). Notre Dame Law Review, Vol. 93, 2017, Forthcoming. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2826201

3. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 11, _ (2017).

4. Paul Goldstein, Intellectual Property-The tough new realities that could make or break your business, 28-30 (Portfolio Hardcover) (2007).

5. In U.S, patents fall into few categories; patent for an invention (product or process), design patent, utility patents, or plant patents. Thai patents are covered 3 different categories; patent for an invention, utility patent and patent of design.

6. NPD Reports on the U.S. Apparel Market 2011, The Devil Wears Trademark” How the Fashion Industry Has Expanded Trademark Doctrine to Its Detriment, 127 Harv. L. Rev., 995, 998 (2014).

7. Shayna Ann Giles, Trade Dress: An unsuitable fit for product design in the fashion industry, 98 J.Pat.&Trademark Off. Soc’y 223, 237 (2016).

8. C. Scott Hemphill & Jeannie Suk, The law, culture and economics of fashion, stanford law review, Vol.61, No.5, 1147, 1148 (Mar 2009).

9. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 1, _ (2017).

10. See Appendix to Opinion of the Court, Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc.and 580 U.S. 18, _ (2017).

11. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 3, _ (2017).

12. Section 101 “Pictorial, graphicand sculptural works” include two-dimensional and three-dimensional works of fine, graphicand applied art, photographs, prints and art reproductions, maps, globes, charts, diagrams, modelsand technical drawings, including architectural plans. Such works shall include works of artistic craftsmanship insofar as their form but not their mechanical or utilitarian aspects are concerned; the design of a useful article, as defined in this section, shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only ifand only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately fromand are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.

13. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 7-8, _ (2017).

14. The Supreme Court refused to clarify if the surface decorations in question were sufficiently qualified for copyright protection by stating that “we do not today hold that the surface decorations are copyrightable. We express no opinion on whether these works are sufficiently original to qualify for copyright protection.” Then, it further stated that “even if respondents [Varsity] ultimately succeed in establishing a valid copyright in the surface decorations at issue here, respondents have no right to prohibit any person from manufacturing a cheerleading uniforms of identical shapes, cutsand dimensions to the ones on which the decorations in this case appear. They may prohibit only the reproduction of the surface designs in any tangible medium of expression-a uniform or otherwise.” See Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 11-12, _ (2017).

15. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 17, _ (2017).

16. Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 1, _ (2017).

17. “To qualify for copyright protection, a work must be original to the author…. Original, as the term is used in copyright, means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works)and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity…. To be sure, the requisite level of creativity is extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice.” See Feist Pubs. Inc., v. Rural Tel. Svc. Co., Inc. 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991).

18. See Design Patents, Department of Intellectual Property, http://www.ipthailand.go.th/th/design-patent-002/item/???????????????????????????????????????.html (Thai) (May 2, 2017)

19. “Article 4…

"Artistic work" means a work of one or more of the following descriptions:

work of painting or drawing, which means a creation of configuration consisting of lines, light, colours or any other element, or the composition thereof, upon one or more materials;

20. Apsara (also spelled as Apsarasa and also known as “Tep Apsar”) is a female spirit of the clouds and waters in Hindu and Buddhist mythology. They are beautiful, supernatural female beings and superb in the art of dancing. The Apsaras were created with the Churning of the Sea of Milk, for the amusement of the Gods. See Khmer Mythology, A Travelers’ Guide to Angkor, http://angkorguide.net/home/home.html, (May 3, 2017).

21. See Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc. 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991).

References

- Buccafusco, C. & Fromer, J.C. (2017). ‘Fashion's Function’. Intellectual Property Law, 93.

- Cases (2017). Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc.,580.

- Cases (1991). Feist Publications, v. Rural Telephone Service Co. Inc., 499

- Cases (2009). Supreme Court case number. 7121/2552; Thai.

- Cases (2012). Supreme Court case number. 12602/2555; Thai.

- Cases (2012). Supreme Court case number. 19305/2555; Thai.

- Department of Intellectual Property (2017). Design Patents. Retrieved May 2, 2017, from http://www.ipthailand.go.th/th/design-patent-002/item/???????????????????????????????????????.html

- Giles, S.A. (2015). Trade Dress: An unsuitable fit for product design in the fashion industry. Journal of the Patent and Trademark Office Society, 98. Available, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/paperscfm?abstract_id=2715146

- Goldstein, P. (2007). Intellectual property-the tough new realities that could make or break your business. Portfolio Hardcover.

- Hemphill, S.C. & Suk, J. (2009). The law, culture and economics of fashion. Stanford Law Review, 61(5), 1147.

- NPD Reports on the US Apparel Market (2011). The devil wears trademark how the fashion industry has expanded trademark doctrine to its detriment. Harvard Law Review, 127.

- Raustiala, K. & Sprigman, C. (2006). The piracy paradox: Innovation and intellectual property in fashion design, Virginia Law Review, 92, 1687

- Terakura, K.K. (2000). Comment, insufficiency of trade dress protection: lack of guidance for trade dress infringement litigation in the fashion design industry. University of Hawaii Law Review, 22.

- Sophie, H.D. (2016). Khmer mythology, a travelers’ guide to Angkor. Retrieved May 3, 2017, from http://angkorguide.net/home/home.html.