Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 1S

Rethinking cybercrime governance and internet fraud eradication in Nigeria

Felix Emeakpore Eboibi, Niger Delta University

Omozue Moses Ogorugba, Delta State University

Citation Information: Eboibi, F.E., & Ogorugba, O.M. (2023). Rethinking cybercrime governance and internet fraud eradication in Nigeria. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 26(S1), 1-14.

Abstract

The increasing involvement of some Nigerian youths in the internet fraud scourge significantly impacts foreign victims and the global economy. This has galvanized the government into reappraising measures toward eradicating cybercrimes. Law enforcement agents now act on intelligence reports, which often arguably turn out to be false alarms. Nigerians are arguably being subjected to unlawful stop and search and invasion of digital devices to clamp down on internet fraudsters. The article argues that the effects of the measures, enactment, and consequent implementation in the fight against cybercrime highlight an undue restriction and violation of Nigerians' rights to privacy and freedom of online speech. It adopts a doctrinal and comparative legal approach and identifies that the implementation of Nigerian Cybercrime legal frameworks, has resulted in the violation of legal provisions protecting Nigerian rights to privacy and online freedom of expression in the guise of eradicating cybercrimes, especially when compared to developed economies. Consequently, the article advocates for a rethink of the current measures towards the eradication of cybercrimes in Nigeria with specific emphasis on: directing cybercrime prevention plans to the primary causes, foreign interventions to the specific Nigerian States where cybercrime is a problem and provision of cybersecurity education and research scholarship fund, restriction of cybercrime investigators from interfering with the rights to privacy and online freedom of speech of unsuspecting members of the public, amendment or repeal of section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015.

Keywords

Cybercrime Governance, Rights to Privacy and Online Freedom of Expression, Internet Fraud, Cybercrime Eradication, Cybercrime Law.

Introduction

The development of information technology infrastructure and the lack of efficient implementation of Nigerian cybercrime legal frameworks have been arguably attributed to the proliferation and/or increase of cybercrimes perpetration in Nigeria. This has resulted in Nigeria being tagged as a safe haven for online fraudsters (Eboibi, 2020a; Richards & Eboibi, 2021, Eboibi, 2018). Although cybercrime does not have an acceptable universal definition, it is seen as a crime perpetrated with computers and information and communication technology infrastructure, either as a tool or a target of the crime. Due to the borderless nature of the crime, the impact of cybercrime or internet fraud in a particular country can be felt in another country without the perpetrator being physically present in the country of the origin of the act or crime. Nigeria, being an African State, contributes immensely to internet fraud attacks against other parts of the globe and cybercrime victims (Cassim, 2011).

Internet fraud is a cybercrime since it is carried out online with the instrumentality of computers or online technology. It is “the uses of Internet services or software with Internet access to defraud victims or to otherwise take advantage of them” (FBI; Gillespie & Magor, 2019). Arguably, it is thought that cybercrime species of internet fraud, 419, investment fraud, and romance scam ensued from Africa. These crimes significantly impact global cybercitizens (Whitty, 2018). The famous 419 scams may have commenced in Nigeria, initially through the instrumentality of handwritten letters via the post office, which has now metamorphosed and increased through the use of emails and social media platforms arising from the development of internet infrastructure in the 1990s and has now expanded to neighbouring African countries such as Benin, Ghana, Senegal, Cameroon, and Côte d’Ivoire including other parts of the world. Internet fraud harms victims financially, emotionally, and psychologically (Brody et al., 2019). It costs billions of dollars globally (Monsurat, 2020). According to the 2019 Internet Crime Report, internet scams have resulted in about $10.2 Billion total losses globally in the past five years (FBI, Internet Crime Report, 2019).

Rising Trend of Nigerian Youths' Involvement in Global Internet Fraud and its Impact on Foreign Countries

The notoriety of some Nigerian youths' involvement in global cybercrime can be traced to the failure of the Nigerian government to cater for its citizens' well-being due to the endemic nature of corruption pervading the country. As Brody et al. (2019) note, “the activities of increasingly corrupt officials over the following two decades affected the wealth of the country adversely and lowered the standard of living of the Nigerian people. To make ends meet, some Nigerians began to devise various fraudulent scams, often with the assistance of other Nigerians in the USA and other developed countries.” Moreover, the President of Nigeria noted in his message to the Chairman of the African Union (AU) during the annual celebration of Africa Anti-Corruption Day on 11 July 2020 thus: “the massive corruption being perpetrated across Africa’s national governments has created a huge governance deficit that has in turn created negative consequences that worsen the socioeconomic and political situation in Africa.” (Edokwe, 2020) The corollary is that political office holders and their cohorts embezzle monies meant to provide infrastructural development in Nigeria, thereby denying Nigerians employment and job security, increased poverty in the country, and lack of finances for capacity building of cybercrime institutions and implementation of cybercrime policies and laws (Eboibi & Ogorugba, 2022).

According to Whitty (2018), concerning the rising trend of youths' involvement in cybercrime from the West African perspective, including Nigeria, “…corruption is the root of all evil acts. The issue of embezzlement is also germane. Monies given out to officials to create infrastructural facilities and even jobs to people are diverted into personal purse. This serves as negative influence on people particularly the youths.” Whitty (2018) further elaborated on the implications of these officials' acts when she stated thus: “the deterioration of the region’s economy and the increased number of unemployed graduates has been a catalyst for cybercrimes. Students are skilled to commit these crimes, and if they foresee little opportunity for employment after their studies, might be tempted into acquiring money by employing their skills in illegal activities to gain money” (Nweke, 2017; Whitty, 2018; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012). The debilitating nature of poverty due to corruption in Nigeria is a stumbling block to the Nigeria government's quest to curtail youths' involvement in cybercrime. As Hassan et al. (2012) note, “African countries [including Nigeria] are bedeviled by various socio-economic problems such as poverty… This limits their strength to effectively combat cyber-crime.”

Based on the preceding, some Nigerian youths now resort to internet fraud being, mostly perpetrated against foreigners to make a living or survive, arguably due to their lucrative currency exchange. According to Chude-Sokei (2010), “official statistics suggest that they bilk the United States of billions of dollars per annum and even more in the UK. Now that they have set their sights on China and India after a generation assaulting Singapore, Australia, Ukraine and everywhere else in the world, there is more for them to gain.” Some Nigerian youths' involvement in internet fraud against foreigners is recently exhibited in a colossal internet fraud in the history of the US in the United States of America vs Emmanuel Oluwatosin Kazeem, Oluwatobi Reuben Dehinbo, Lateef Aina Animawun, Oluwaseunara Temitope Osanyinbi and Oluwamuyiwa Abolad Olawoye and United States of America v Michael Oluwasegun Kazeem (2015).

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission has decried the rising trend of internet fraud perpetration by some Nigerian youths. The statistics from the EFCC (2021) show that from April to June 2021, a total of 402 suspects were arrested in the Lekki area of Lagos alone. Again, the EFCC (2021) recorded 33 internet fraud convictions within 24 hours which has heightened the fear that 70 percent of Nigerian youths would soon become ex-convicts with the rising trend of cybercriminality if nothing whatsoever is done about the situation (Nwezeh & Shittu, 2021). Recently, Justice Taiwo O. Taiwo of the Federal High Court, Abuja, reiterated Nigerian youths' increasingly involvement in internet fraud in the case of the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Aifuwa Courage Osasumwen (2021) where the defendant fraudulently impersonated one Van Diesel, a United States citizen through a Facebook account in order to obtain money from one Patty Burner, contrary to section 22 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 (Suit No: FHC/ABJ/CR/78/2021). Although the defendant pleaded guilty, Justice Taiwo released him on probation and stated thus: “Given the prevalence of cybercrimes and echoing the fears of the current Chairman of the EFCC, if care is not taken, 70% percent of our youth may be termed ex-convicts and our society is doomed” (Suit No: FHC/ABJ/CR/78/2021). Also, in the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Hassan Adesegun Adewale (2019), the defendant defrauded one Larry O’bren $1000 by fraudulently impersonating one Jessy West Reade through his Gmail account which he uses in engaging in internet dating scam contrary to Section 22 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015. While sentencing the defendant to one year imprisonment contrary to the plea bargain agreement, Justice Abdulmalik (2019) stated thus: “I sincerely without ado frown seriously at the prevalence of this type of offence amongst youths in Nigeria, who should otherwise be engaged in their educational pursuit. The offence of internet fraud otherwise popularly known as “yahoo yahoo” in Nigeria has greatly depreciated the image of this country in the international community. The commission of this offence is a serious one and should attract more than a tap on the wrist as is the sentence agreement of six months reached by the EFCC, Ibadan zonal office and the Defence” (Suit No: FNC/1B/52C/2019).

This is further complicated with internet fraud institutions and academies springing throughout Nigeria, where internet fraud skills and techniques are being taught to benefit youths (Sahara Reporters, 2019; EFCC, 2019a)

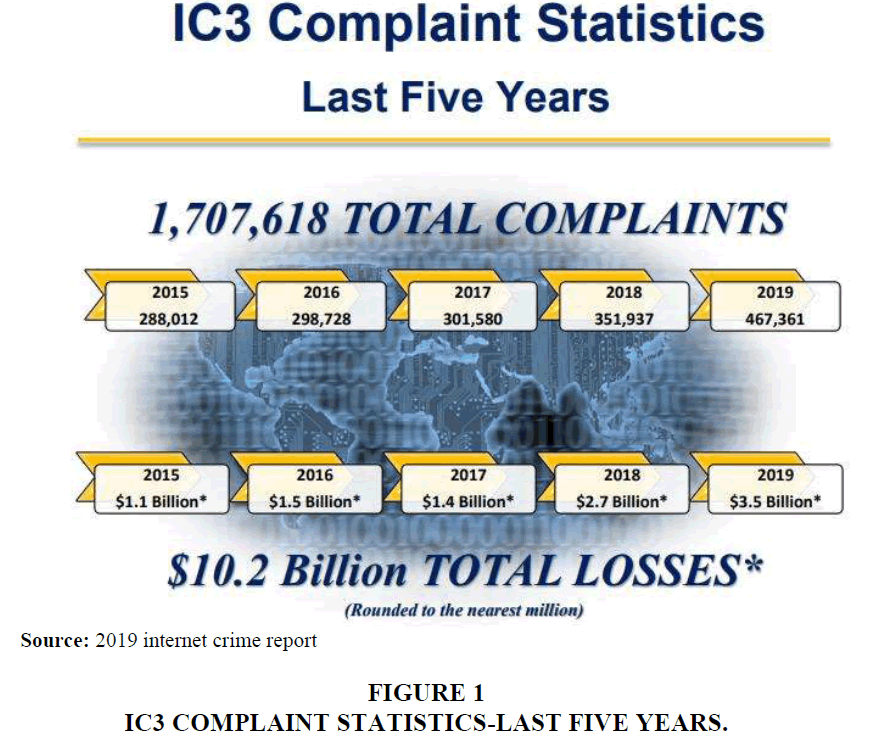

The involvement of Nigerian youths in cybercrime has caused the global proliferation of cybercrimes (internet scams) and consequent financial losses. According to the 2019 Internet Crime Report, there is a yearly increase of cybercrime perpetration globally. Thus, it is represented (Figure 1):

The report implies that between 2015 and 2019, there was about 1,707,618 total cybercrime (internet scams) complaint with total global financial losses of $10.2 Billion. While there was a yearly increase in cybercrime complaints and financial losses, the differences in the increase between 2015 and 2019 are worrisome, hence the need for Nigerian youths to be discouraged from perpetuating cybercrimes by the Nigerian government and the international community. For instance, there were 288, 022 complaints and $1.1 Billion in losses in 2015, which unfortunately increased to 467,361 complaints, and $3.5 Billion in losses in 2019 (Annual Report, 2019).

Eradicating Cybercrime in Nigeria and Rights to Privacy and Freedom of Expression

Undoubtedly, the previous section shows the growth of Nigerians' involvement in global cybercrime. Despite the development of ICT and the increase in internet users in Nigeria, adequate measures seem not to have been arguably put in place by the Nigerian government to eradicate cybercrimes. Although the Nigerian government enacted the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc.) Act 2015, as Bidemi (2017) rightly notes, “There are undue restriction, intervention, incessant attacks on the use of Internet and enactment of several obnoxious rules against Internet resources by some of African governments in the pretence of safeguarding…cybercrime…” He noted further thus: “…many African governments have resulted to violating peoples’ freedom of expression under the guise of fighting against … cybercrimes…” (Bidemi, 2017) including the right to privacy. This has resulted in questions concerning the legitimacy and effectiveness of the current measures being applied in the quest to eradicate cybercrimes in Nigeria, especially when juxtaposed against the capacity, the intelligence of law enforcement agents and available infrastructures.

Nigeria's Cybercrime Legal Frameworks and Right to Privacy

The challenge concerning the implementation of the Nigerian legal frameworks against citizens is the unlawful trampling of the right to privacy by law enforcement agents in the guise of fighting cybercrime. When law enforcement agents decide to fight against cybercrime by getting hold of individuals' digital devices, it is subject to constitutional and statutory prerequisites. These conditions show the high regard for and protection of individual owners' privacy and abhor governmental intrusion (Hellums, 2002).

Interestingly, the successful investigation and prosecution of cybercrimes and internet fraudsters require the extraction and use of electronic evidence that links perpetrators to the crime commission. The challenge for law enforcement agents is where owners of digital devices and electronic platforms insert technological security features and password encryption. The most likely way to bypass such features to gain unrestricted access is to coerce the owner or person in control of the digital device or electronic platform to surrender the same to facilitate their investigation (Govender, 2018).

Some members of the Nigerian Police Force are in the habit of harassing, embarrassing, torturing, and unlawfully searching bags, mobile and smart devices of innocent Nigerians going about their lawful duties on the ground of fighting internet fraud. They assume that every bag contains a laptop. They also consequently seize the laptops and mobile phones of Nigerians and compel them to release such digital devices' security features to enable them to gain access to the devices to search them. Akindare Okunola (2018) gives an insight into his experience with the Nigerian Police thus:

“If you are a young Nigerian man, there is a high chance that at some point, you will get stopped and risked/harassed by the Nigerian police. At the point of harassment, you may hear things like “What do you do for a living?”, “Bring out your laptop”, “Unlock your phone” most likely the last two. During my service year in Ebonyi State, I’d often get stopped by the police on my way to/from Abakaliki… Sometimes, they’d ask me to bring out my laptop or unlock my phone so they could go through it-reason being I might be a “Yahoo Boy” also known as cash cows (for them) (Okunola, 2018)”.

Again, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission is notorious for swooping on citizens alleged to be internet fraudsters in public places(hotels, clubs, schools) and arrest them before investigation on allegations of intelligence reports, which most times arguably end up to be a false alarm (EFCC, 2019b; Vanguard News, 2019; EFCC, 2020a & 2020b).

These acts by law enforcement agents violate the rights to privacy of those arrested as enshrined in section 37 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended)-CFRN. It provides that “The privacy of citizens, their homes, correspondence, telephone communications and telegraphic communications is hereby guaranteed and protected.” Also, in the US, the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution provides thus: “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects [] against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated…” Similarly, Section 14 of the South African Constitution notes, “Everyone has the right to privacy, which includes the right not to have their person or home searched; their property searched; their possessions seized; or the privacy of their communications infringed.” This implies that in the absence of a lawful order or warrant for the search and seizure of digital devices in the course of investigating cybercrimes or internet fraud by law enforcement agents, such a search and seizure is a violation of the person’s right to privacy, dignity, freedom, security, and property.

It might be argued pursuant to section 45 of CFRN that this right can be violated by law enforcement agents in the interest of public safety, health, defense, and order. This is not correct because, in the first place, the arrest must be lawful, and the order of the court or a search warrant must be obtained from the Federal High Court before digital devices (mobile phones, laptops etc.) can be searched and seized. Anything short of this is a breach of the individual right to privacy. Interestingly, the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 is a comprehensive law on computer and cybercrime-related matters (including internet fraud), and it is made subject to the observance of the right to privacy concerning law enforcement agents' power to arrest, search, and seizure. Section 45 of the Act subjects law enforcement agents to “apply ex-parte to a judge in chambers for the issuance of warrant” to search and seize digital devices to obtain electronic evidence in a cybercrime-related investigation. Since section 50 of the Act equips the FHC of jurisdiction to entertain cybercrime matters, such an application ought to be brought before the FHC judge. Arguably, in the absence of any warrant before the encroachment of persons' digital devices, it is nothing but a violation of their digital right to privacy.

The implication is that searches and seizures carried out without the required permissions are unlawful and breach the individuals' right to privacy concerning the digital device. According to the case of Schneckloth v. Bustamonte (1973), a search and seizure of a digital device may be held to be lawful if the owner or the person in control consents. However, as the US federal district court case of United States v. Blas (1991) implies, a consent to “look at” a digital device does not guarantee law enforcement agent legal authority to examine or go through its memory neither does it allow a forensic examination of the said device. Furthermore, in the California case of United States v. Arnold (2006) a laptop computer, a separate hard drive, a computer memory stick, and six compact discs were discovered upon a search on the defendant’s bag and baggage. When construing whether the government can access stored information in the digital devices in the absence of a search warrant, they acknowledged that the present advancement of technology like those belonging to the defendant “permit individuals and businesses to store vast amounts of private, personal and valuable information within a myriad of portable electronic storage devices.” Hence, digital evidence derived from them must be subject to a search warrant. In the absence of that, the evidence obtained therein was suppressed (Stillwagon, 2008).

Moreover, the US case of Steve Jackson Games, Inc. v. United States Secret Service (1994) demonstrates that a court order or warrant is required for lawful search and seizure of computer software, computer hardware, electronic mail, and stored electronic communications. This is further reinforced by Waxse (2016), thus: “Because an individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy in the content of text messages and emails, just as with letters and phone calls, a warrant citing grounds for probable cause and based on a certain particularity is required.” The Nigerian government and its cybercrime institutions need to understand these and adapt the same.

According to the Nigerian case of Mr Anthony Okolie v. The Director General, State Security Service & 2 Ors (2020), an arrest and detention of a defendant or suspect for a crime before investigation is illegal, unconstitutional and void (Suit No: FHC/ASB/CS/3/2020).

The court questioned why law enforcement agents do not undertake a preliminary investigation into crimes to determine whether or not suspects are linked with crimes sought to be investigated before swooping on them. Nigeria law enforcement agents need to adopt the modus operandi of the US law enforcement agents in the investigation of internet fraud. From the experiences of United States of America v Emmanuel Oluwatosin Kazeem, Oluwatobi Reuben Dehinbo, Lateef Aina Animawun, Oluwaseunara Temitope Osanyinbi and Oluwamuyiwa Abolad Olawoye and United States of America v Michael Oluwasegun Kazeem (2015) and United States of America v. Valentine Iro & 79 others (2019) investigations were concluded before the defendants were arrested and subsequently charged to court (United States District Court, District Court of Oregon; US District Court, Central District of California).

Proponents of the search-incident to arrest theory may justify the validity of the search of digital devices of internet fraudsters contemporaneously to arrest. The fact that EFCC operatives arrest and confiscate mobile phones and laptops of internet fraudsters arguably without a lawful order and subsequently carry out a forensic examination of these devices to fish for evidence hours, days and weeks thereafter in their offices to prosecute the suspects underscores the in applicability of the incident to arrest theory. According to the case of the United States v. Park (2007) where the defendant’s cell phone was searched one and a half hours after the defendant’s arrest, the court held that the defendant’s arrest was not contemporaneous. The incident to arrest exception is bound to fail when it relates to the search of mobile phones and laptop computers. The Florida Supreme Court in the case of Smallwood v. State (2013) determined whether a law enforcement agent based on the search-incident-to arrest exception can “search through photographs contained within a cell phone which is on an arrestee's person at the time of a valid arrest, notwithstanding that there is no reasonable belief that the cell phone contains evidence of any crime [.]” Before the trial court, the defense counsel had argued that the law enforcement agent search of the defendant cell phone is in breach of his right to privacy while the Prosecutor likened the phone to a container or wallet hence searchable based on an incident to a legal arrest. The court likened the search of a cell phone to a search of a home office and held that the search of a cell phone to acquire data or evidence against a defendant in the absence of the appropriate warrant is unconstitutional. In arriving at the determination of the unconstitutionality of search of the phone without a warrant, the court stated thus:

“Modem cell phones can contain as much memory as a personal computer and could conceivably contain the entirety of one's personal photograph collection, home videos, music library, and reading library, as well as calendars, medical information, banking records, instant messaging, text messages, voicemail, call logs, and GPS history. Cell phones are also capable of accessing the internet and are, therefore, capable of accessing information beyond what is stored on the phone's physical memory. For example, cell phones may also contain web browsing history, emails from work and personal accounts, and applications for accessing Facebook and other social networking sites. Essentially, cell phones can make the entirety of one's personal life available for perusing by an officer every time someone is arrested for any offense…”

Nigeria's Cybercrime Legal Frameworks and Right to Freedom of Expression

Apart from violations of the right to privacy arising from search and seizure of digital devices in Nigeria, the enactment of cybercrime legal frameworks and policies is being used to empower the Nigerian government’s breach of other rights concerning internet freedom of speech and information online. As the Digital Rights in Africa Report (2016) notes: “cybercrime legislation has been passed, or is being considered, in Nigeria, Algeria, Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. A significant proportion of arrests of bloggers and active citizens online were done using the instrument of cybercrime legislation.”

As noted in the previous section, the Nigerian government enacted the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 “…to provide an effective, unified and comprehensive legal, regulatory and institutional framework for the prohibition, prevention, detection, prosecution and punishment of cybercrimes in Nigeria.” However, section 24 of the Act proscribes cyberstalking similar to sections 23 and 27 of the Kenyan Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act and section 29 of the Kenyan Information and Communication Act, which infringes Nigerians' internet freedom (Eboibi, 2020a; Eboibi & Robert, 2020; Eboibi, 2020b; Eboibi, 2018).

Again, the Nigerian Court of Appeal refused to declare the said section unconstitutional contrary to the express provision of section 39, guaranteeing the right to freedom of expression in Solomon Okedera v. Federal Republic of Nigeria (2019). This is despite bringing to the knowledge of the court the Indian Supreme Court judgment in Shreya Singhal v Union of India (2013) where section 66A(which is similar to section 24(1) of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015) was declared null, void and unconstitutional because of the wordings and vagueness of the provision and the Kenyan case of Geoffrey Andare v Attroney General (2015) where Ngugi J., declared thus: “section 29 imposes penal consequences in terms which I have found to be vague and broad, and in my view, unconstitutional for that reason.” According to Amnesty International (2019):

“Since the passage of the Cybercrimes Act, Nigerian authorities and their agents have frequently used the provisions of the Act, particularly section 24, to harass, intimidate, arbitrarily arrest and detain, and unfairly prosecute journalists, bloggers and media activists who express views perceived to be critical of the government, whether at the federal or state levels, and of government officials… The Act does not define use of vague terms like “inconvenience,” “annoyance” or “insult” which leaves room for vague interpretation and further makes it easy to be used to harass journalists, bloggers and media practitioners” (Adibe et al., 2017).

Rethinking Eradication of Cybercrimes in Nigeria

The previous sections have shown the perpetration of cybercrimes by some Nigerian youths, the impact on foreigners, and its contribution to the proliferation of global cybercrimes. The preventive attempts and measures by the Nigerian government through cybercrime legal frameworks have arguably not deterred these crimes but instead resulted in violations of Nigerians' rights to privacy and online freedom of expression. Considering the enormous impact of these crimes on foreigners, this section examines how the Nigerian government, foreign countries or governments and generally the international community can assist Nigeria in fighting cybercrimes.

Direct Cybercrime Prevention Plans to the Primary Causes Instead of the Symptoms

One of the major identified problems concerning the resort to cybercrime by Nigerian youths is unemployment. There are limited job opportunities, a lack of investment opportunities, and employment growth. Consequently, the first point of call is for the Nigerian government, foreign governments or the international community to garner efforts towards circumventing this problem before responding to ways of preventing cyberattacks. This has to be prioritized due to the proliferating nature of the Nigerian population projected to reach over 400 million by 2050 (Sasu, 2022). The colossal impact of this on crime and employment cannot be imagined.

Undoubtedly, Western countries give financial aids and material assistance to Africa, including Nigeria to fight several problems. Specifically, Europe gives more than €21 billion yearly in development aid in Africa. However, corruption, poverty, absence of good governance, and weak institutions undermine the effectiveness of the utilization and impact of the aids (Mills, 2020). According to Amenawo Ikpa Offiong et al. (2020) “as a result of the corruption index, there was a significant negative effect of foreign aid on the growth rate of Nigeria economy in the long-run…” Consequently, Mills (2020) rightly argues in support of the change of aid patterns to African countries, considering “the consequences of failing to change current aid practices in Africa are moot. The combination of rapidly increasing populations plus fragile and often corrupt systems of governance producing insufficient and elite-focused economic opportunities can only end badly.” Instead of giving cash assistance directly to the Nigerian government for development, foreign governments and donor agencies should identify areas where employment can be created, build the industries and infrastructures directly and ensure that an integrity process is enunciated to absolve qualified Nigerian youths. Monies should not be given to the Nigerian government, as experience has shown, such monies are likely to be embezzled; neither should they employ directly because they will arguably employ their children, cronies, and relatives even when they are not qualified.

Direct Foreign Interventions to the Specific Nigerian States Where Cybercrime is a Problem

There is a need for a pragmatic approach toward assisting Nigeria in the fight against cybercrimes via an increase in international cooperation by western countries of the US, UK and Australia in Nigeria. More direct awareness needs to be created in Nigeria, assisting in strengthening Nigeria cybercrime legal frameworks devoid of breaches of rights to privacy and online freedom of expression by offering legal drafting services and intervention at the early stages of considering these laws, capacity building for law enforcement agents, and the sharing of information. It might be argued that some foreign countries are already involved in the above approach. Arguably, these approaches and interventions suffer from specificity concerning their implementations (Lusthaus, 2020). Consequently, foreign countries should identify by drawing a list of the Nigerian States where cybercrime perpetration and cybercriminality is a safe haven and where most internet scams emanate and channel foreign financial aid and capacity building of law enforcement agents. Lagos, Abuja, Ibadan, Illorin and Benin should be of utmost priority. This is cost effective utilization of the aids made available and likely to have the greatest effect (Lusthaus, 2020). Concerning the capacity building of law enforcement agents, there is a need to take specific cognizance of junior officers who are always in the field and mostly involved in the day to day enforcement responsibilities rather than senior officers who reside in air-conditioned offices. Computer and digital forensics capacity building for Nigerian law enforcement agents to facilitate their ability to investigate and prosecute perpetrators of cybercrimes adequately cannot be overestimated, and consequently the provision of forensic laboratories and facilities.

In another development, Lusthaus (2020) suggests approaches foreign governments and donor Agencies could be of assistance towards the fight against cybercrimes devoid of rendering financial aids directly. He highlighted the need-based approach that has to do with the exchange of capacity building programs and availing training programs to benefit cybercrime investigators in areas where there are high cyber threats, including anti-corruption initiatives, especially concerning Nigeria where endemic corruption affects adequate law enforcement. Again, the foreign fund or aid should be directly deployed to put in place cybercrime detection, prevention, development of human resources, and cybersecurity infrastructures instead of giving the monies to the Nigerian government.

Provision of Cybersecurity Education and Research Scholarship Fund

Considering the recent springing up of Internet fraud Academies and centres which has been noticed in different parts of Nigeria, where internet fraud skills and techniques is being taught to Nigerian youths to scam mostly foreigners, there is a need for the provision of scholarship to enhance specialized training to improve computing and cybersecurity education to divert potential cybercriminals, internet fraud students and young technologists from these academies. This will also introduce them to legitimate career paths in the computer industry and facilitate skilled migration and labour mobility within Nigeria and the African region (Lusthaus, 2020). The United Kingdom government is currently practicing such an agenda through the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). The international community and specifically the UK government should directly replicate similar ventures in Nigeria. The NCSC ‘Education and Research’ agenda “partners in government, industry, and academia.” They “identify and support excellence in cybersecurity education and research and encourage industry investment in academic research” (Eboibi, 2020a; NCSC, ‘Research and Academia’). As part of the agenda, “19 UK universities have been recognized as Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research (ACE CSR) to conduct international cybersecurity research” with the provision of grants and scholarships to Doctoral Students under the “ACEs-CSR agenda and three centres have been recognized for Doctoral Training in cybersecurity: The University of Bristol with the University of Bath Royal Holloway, University of London and University College London” (Eboibi, 2020a; NCSC, Research and Academia). There are also cybersecurity education higher degrees at the Masters level and a Cyber First program and degree apprenticeship. The Cyber First program is for the benefits of 11–19-year-olds. The program has been in existence since May 2016 for the benefit of young persons that have technology zeal. The accompanied bursary for individuals is about £4,000 as financial assistance to undergraduates to participate in cyber-related training while undergraduates under the degree apprenticeship collect money during learning (Eboibi, 2020a; NCSC, Research and Academia). The introduction of similar ventures in Nigeria would be an added advantage towards the fight against cybercrime, especially with some Nigerians' poor nature and their inability to see themselves through in schools.

Restrain Law Enforcement Agents from Violating Rights to Privacy and Online Speech

The Nigerian Cybercrimes Act empowers law enforcement agents to curtail the proliferation of cybercrimes. In carrying out this task, as shown in the previous section, some law enforcement agents are arguably in the habit of arresting and searching digital devices of unsuspecting members of the public before investigation, thereby infringing on their privacy rights to the digital devices. To forestall these occurrences, there is a need to educate cybercrime investigators to desist from effecting arrests of unsuspecting members of the public when investigations have not been concluded or a determination made as to the involvement of an individual in a cybercrime offence. The decision of the court in the aforementioned case of Mr Anthony Okolie v. The Director General, State Security Service & 2 Ors (2020) is very apt in this regard. Again, sensitization of cybercrime investigators of the unlawfulness of seizure and search of digital devices of unsuspecting members of the public is paramount. Section 37 of the CFRN and Section 45 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 (requesting for issuance of a warrant or court order) should be brought to their knowledge. Unless a cybercrime investigator is in possession of a warrant, no attempt should be made to gain access to digital devices of unsuspecting members of the public in the guise of eradicating perpetrators of internet fraud. The US case of United States v. Klinger (2008) gives a practical example of what Nigerian cybercrime investigators should do when digital devices are found in possession of unsuspecting members of the public during a lawful arrest. The idea is to keep the digital devices in safe custody without searching the same and apply for court order or warrant for search of the digital device to be carried out. In another development, Nigerians must begin to explore the opportunities provided under sections 46, 35 and 37 etc. of the CFRN to seek redress under the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules 2009 for a declaration of breach of the right to privacy concerning their digital devices and unlawful arrest before the conclusion of investigation for the award of damages and public apology.

Again, the Nigerian government must respect its obligations under Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (1966), Articles 9 & 19 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Right (ACHPR) 1981 and the consequent Resolutions by the African Commission on Human and Peoples (2021) Rights and the United Nations General Assembly. Human Rights Council declaring freedom of online speech and internet access as human rights. Using section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 to gag online freedom of speech of Nigerians in the guise of fighting cybercrimes is a gross violation of its international human rights obligations. Although the case of Solomon Okedera v. Federal Republic of Nigeria (2019) refused to declare section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 unconstitutional, recently the Court of Justice of ECOWAS in the case of The Incorporated Trustees of Laws and Rights Awareness Initiatives v Federal Republic of Nigeria (2018). ordered the Nigerian government to amend or repeal the provisions of section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes act 2015. The Court stated thus:

“That the Defendant State, by adopting the provision of section 24 of Cybercrime (Prohibition, Prevention, etc.) Act 2015, violates Articles 9(2) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and 19(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights…Consequently, it orders, the Defendant State to repeal or amend section 24 of the Cybercrime Act 2015, in accordance with its obligation under Article 1 of the African Charter and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights” (Judgment No ECW/CCJ/JUD/16/20).

Unfortunately, the above judgment is being observed in breach despite being handed down more than one year ago. The Nigerian government should endeavour to adhere to the judgment as it is a fulfillment of her obligations under the human rights instruments.

Conclusion

This article shows the involvement of Nigerian youths in the perpetration of cybercrimes, mostly against foreigners. Endemic corruption in Nigeria, resulting in unemployment and lack of infrastructural development, has been identified as one of the major causes Nigerian youths resort to internet fraud. This greatly impacts foreign victims and the global economy and contributes to the proliferation of global cybercrimes. More so, cybercrime investigators are arguably affected by the absence of finance to acquire the necessary competence and facilities to investigate and prosecute perpetrators of internet fraud compared to what is obtainable in other developed countries. Based on the preceding and the growth of unemployed graduates from tertiary institutions, interned fraud perpetration will be challenging to curtail in Nigeria, which will continue to impact foreign victims and the international community, except the suggested measures in this article are implemented. Although the Nigerian government reacted by enacting cybercrime legal frameworks to curtail the menace, the corollary is that internet fraud perpetration by Nigerian youths has continued to proliferate, and Nigerians' right to online speech is being violated in the course of implementation. Similar provisions of section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 have been declared unconstitutional, null and void in the Indian and Kenyan cases of Shreya Singhal v Union of India (2013), and Andare v Attroney General respectively for violating the right to online expression, and the recent judgment of the Court of Justice of ECOWAS requests Nigeria to amend or repeal the same. However, the Nigerian government is still empowering law enforcement agents to implement observance of the said section in the guise of fighting cybercrime. The privacy of digital devices of unsuspecting members of the public is legally challenged by the Nigerian legal frameworks and its implementation as it concerns the balancing of individual rights and the fight against internet fraud and cybercrime in Nigeria. Nigerians and unsuspecting members of the public are being subjected to unlawful arrest, search and seizure of their digital devices despite the express protection provided under section 37 CFRN, section 45 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015 and the case of Mr Anthony Okolie v. The Director General, State Security Service & 2 Ors. Again, the current measure of Nigerian cybercrime investigators, when compared to other jurisdictions, did not pass the test of legality, as shown in the cases of United States v. Blas, Steve Jackson Games, Inc. v. United States Secret Service and United States v. Klinger. Nigeria law enforcement agents need to adopt the modus operandi of the US law enforcement agents in the investigation of internet fraud. From the experiences of United States of America v Emmanuel Oluwatosin Kazeem, Oluwatobi Reuben Dehinbo, Lateef Aina Animawun, Oluwaseunara Temitope Osanyinbi and Oluwamuyiwa Abolad Olawoye (2015) and United States of America v Michael Oluwasegun Kazeem and United States of America v. Valentine Iro & 79 others (2019) investigations were concluded before the defendants were arrested and subsequently charged to court. Moreover, several measures have been raised in this article to improve cybercrime governance and enhance the eradication of cybercrimes in Nigeria. There is a need for the Nigerian government, with the assistance of foreign countries or the international community to: Direct cybercrime prevention plans to the root causes instead of the symptoms, direct foreign interventions to the specific Nigerian States where cybercrime is a problem and provision of cybersecurity education and research scholarship fund, restriction of cybercrime investigators from interfering with the rights to privacy and online freedom of speech of unsuspecting members of the public, amendment or repeal of section 24 of the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015. If well implemented, these measures will help in the global quest to eradicate or curtail cybercrimes emanating from Nigeria and Nigerian cybercriminals.

References

Abdulmalik. (2019). Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Hassan Adesegun Adewale, Suit No: FNC/1B/52C/2019. Judgment delivered on 27 May 2019 by Justice J.O, Ibadan.

Adibe, R., Ike C.C., & Udeogu, C.U.(2017). Press freedom and Nigeria’s cybercrime act of 2015: An assessment. Africa Spectrum, 52(2), 117-127.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

African Commission on Human and Peoples. (2021). Final Communique of the 59th Ordinary Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

Amnesty International. (2019). Endangered voices: attack on freedom of expression in Nigeria.

Bidemi, B. (2017). Internet diffusion and government intervention: The parody of sustainable development in Africa. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, 10(10), 11-28.

Brody, R.G., Kern, S., Ogunade, K. (2019). An insider’s look at the rise of Nigerian 419 scams. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(1), 202-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Cassim, F. (2011). Addressing the growing spectre of cybercrime in Africa: evaluating measures adopted by South Africa and other regional role players. Comparartive and International Law Journal of Southern Africa, 44(1), 123-138.

Chude-Sokei, L. (2010). Invisible missive magnetic juju: On African cybercrime.

Digital Rights in Africa Report. (2016). Paradigm Initiative Nigeria.

Eboibi, F.E. (2018). Handbook on Nigerian cybercrime law. Justice Jeco Printing & Publishing Global.

Eboibi, F.E. (2020a). A critique of the cyberstalking offence under the Nigerian Cybercrimes Act 2015. Computers and Telecommunication Law Review, 26(6),176-177.

Eboibi, F.E. (2020b). Concerns of cyber criminality in South Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia and Nigeria: rethinking cybercrime policy implementation and institutional accountability. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 46(1), 78-109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Eboibi, F.E., & Ogorugba, O.M. (2022). Cybercrime regulation and Nigerian youths increasing involvement in internet fraud: Attacking the roots rather than the symptoms. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues.

Eboibi, F.E., & Robert, E. (2020). Global legal response to coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact: perspectives from Nigeria, the United States of America and the United Kingdom. Commonwealth Law Bulletin, 593-624.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. (2021). Lekki now hotbed of cybercrime-EFCC 402 suspects arrested in three months.

Edokwe, B. (2020). Buhari writes South African President, laments huge corruption in govt.

EFCC. (2019a). EFCC arrests proprietor. Students of Yahoo Yahoo School.

EFCC. (2019b). EFCC storms yahoo-boys party in Osogbo. Arrests 94 Suspects.

EFCC. (2020a). EFCC arrests 89 yahoo boys in Ibadan night club.

EFCC. (2020b). EFCC arrests hotelier, 79 others in Lagos for internet fraud.

Gillespie, A.A., & Magor, S. (2019). Tackling online fraud. Europäische Rechtsakademie (ERA) Forum.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Govender, T.F. (2018). A critical analysis of the search and seizure of electronic evidence relating to the investigation of cybercrime in South Africa. L.L.M Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, 18, 31.

Hassan, A.B., Lass, F.D., & Makinde, J., (2012). Cybercrime in Nigeria: Causes, effects and the way out. Journal of Science and Technology, 2(7), 626-631.

Hellums, S.D. (2002). Bits and Bytes: The Carnivore Initiative and the Search and Seizure of Electronic Mail. William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, 10(3), 827.

Internet Crime Report. (2019). Federal bureau of investigation, internet crime complaint center. 2019 Internet Crime Report, 5.

Lusthaus, J. (2020). Cybercrime in Southeast Asia: combating a global threat locally. Australian Strategic Policy Institute: International Cyber Policy Center, 29(3), 1-7.

Mills, G. (2020). The African security intersection: Pathways to partnership.

Monsurat, I. (2020). African insurance (Spiritualism) and the success rate of cybercriminals in Nigeria: A case study of yahoo boys in Illorin, Nigeria. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 14(1), 300-315.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Nweke, O.J. (2017). The rapid growth of internet fraud in Nigeria: Causes, effects and solutions by Moses Calceus. Inner temple OOU.

Nwezeh, K., & Shittu, H. (2021). 70% of Nigerian Youths May Soon Become Ex-convicts, Says EFCC. ThisDayLive.

Offiong, A.I., Etim, G.S., Enuoh, R.O., Nkamare, S.E., & James, G.B. (2020). Foreign aid, corruption, economic growth rate and development index in Nigeria: The ARDL approach. Research in World Economy, 11(5), 358-359.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Okunola, A. (2018). Can the Nigerian police stop and search you and look through your email?

Richards, N.U., & Eboibi, F.E. (2021). African governments and the influence of corruption on the proliferation of cybercrime in Africa: wherein lies the rule of law? International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 35(2), 131-161.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Sahara Reporters. (2019). EFCC arrests 23 men from ‘yahoo-yahoo’ school.

Sasu, D.D. (2022). Forecasted population in Nigeria in selected years between 2025 and 2050.

Smallwood v. State. (2013). Cedric Tyrone smallwood, Petitioner, v. STATE of Florida, Respondent.

Stillwagon, B.A. (2008). Bringing an end to warrantless cell phone searches. Georgia Law Review, 42(4) 1175-1177.

Vanguard News. (2019). EFCC frees 13 out of 94 ‘Yahoo Boys’ arrested in Osogbo nightclub ON OCTOBER 16, 2019.

Waxse, D.J. (2016). Search warrants for cell phones and other locations where electronically stored information exists: the requirements for warrants under the fourth amendment. Federal Courts Law Review, 9(3), 1-4.

Whitty, M.T. (2018). 419-It’s just a game: Pathways to cyberfraud criminality emanating from West Africa. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 12(1), 97.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Whitty, M.T., & Buchanan, T. (2012). The online romance scam: A serious crime. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(3), 181-183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross ref

Received: 26-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12386; Editor assigned: 29-Jul-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-22-12386(PQ); Reviewed: 09-Aug-2022, QC No. JLERI-22-12386; Revised: 29-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-12386(R); Published: 06-Dec-2022