Review Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 2S

Re-Streamlining the Capitalist's World History on Political Economy Thought

Mohd Rosdi M.S, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Richard Jackson, University of Otago

Citation Information: Rosdi, M.S.M., & Jackson, R. (2022). Re-streamlining the capitalist’s world history on political economy thought. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(S2). 1-10.

Keywords

Re-Streamlining, Capitalist World History, Political Economy Thought

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine the history of the world from the perspective of political economy. The focus on this study is to streamline the history of political economy's scholarship in relation to capitalism. Political economy is a field that is very challenging for many scholars to understand, falling between the science of political economy and the science of economics and politics as separate disciplines. Discussion in this field can be complicated when many scholars from various backgrounds contribute their ideas. Therefore, there appear to be two problems. Firstly, the author wondered when research began in the field of the political economy. Were the early scholars of political economy from the economic circle or from the political circle? Secondly, in the clash of ideas as many scholars built a framework of understanding in political economy, who were recognised as the accurate scholars in the field? Based on a study of documents and content analysis, this paper will re-streamline the history of the political economy. From this, political economy can be seen as a field closely aligned with ideology. It can be formed from the capitalist ideology, namely Smith and Ricardo, or from the communist ideology, namely Marxism. From the scholars’ discussion on political economy in capitalism, the author established that the first country to discuss political economy was France in the 16th Century. Following that, the idea was discussed in Spain, Scotland, Britain, Italy, United Kingdom, Austria, Norway, and by American scholars.

Introduction

In the political economy field, Adam Smith with his book entitled The Wealth of Nation was an influence for David Ricardo, and John Maynard Keynes expected to continue Smith’s ideology after rebutting the Mercantilism System in Europe in the 18th Century. They intended continuing the theory of economic development from The Wealth of Nation from an economist’s perspective (Cole, Cameron & Edwards, 1991). From the communism perspective, Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto also expanded the ideology to embody government and control of a state such as Germany (Wang, 1977). The accumulation of this can build a compact heritage of knowledge on political economy; it is called the classical political economy.

The whole of the history of political economy could be encompassed from the economic development field. This could be difficult due to the conflict of ideology between the capitalist ideology and communist ideology because proponents of each claim that their ideology is more implemented and relevant (Riemer & Simon, 1997). To avoid this conflict, an initiative appeared to build a groundswell of nations with the new political economy perspective. The construction of the idea aimed at the welfare state came up in some countries to avoid the old ideological conflict and returned to the idea of preserving the well-being of mankind; it is called the new political economy.

To understand more about the new political economy perspective, it needs to be set in an historical context. There have the meaning and causes why the political economy field it’s too important to implement in a country. In fact, most probably the accuracy of the political economy knowledge in contemporary scholarship can be understood after considering the contribution of the legendary scholars in discussing political economy from economic development. Eventually, this article intends to re-streamline the history of the political economy from the classical political economy, whether from legendary scholars or contemporary scholars.

The Capitalist’s World History on the Political Economy Thought

Political economy intertwines and combines two words: the politic and the economic (MacLeod, 1875; Mohd Rosdi, 2014). Typically, politics illustrates an ideology coming from two groups of ideologies, capitalism or communism. Politic comes from civitas, extending its application to society or the nation at large. They are thinking about how to increase their profit rather than how to meet the needs of the community at large. For economic, there is some particular thinking about economic growth or contraction. Economy according to the Greeks, is the household. It comes from oikos meaning house and nomos meaning the law (Amemiya, 2004; Cameron, 2008). The idea that there is a relationship between political and economic processes thus has a long historical lineage.

It is beyond the scope of this introduction to discuss the extent to which contemporary political economy represents a long-standing research tradition’s current understanding of how economic and political processes interact, and how they should be studied, or whether it is to some extent a new research tradition. Continuities and discontinuities in our perceptions of the relationship between the political and economic spheres have been discussed elsewhere, sometimes at great length (Caporaso & Levine, 1992).

Firstly, the history of political economy should have some knowledge of the science of political economy. From the 16th Century, knowledge was produced in association with wealth management1 in France. Say (1880) noted that these ideas came from Botero, Antonio Serra, Davanzati, Belloni, Carli, Algarotti2, Genovesi3, The Abbe Galiani, and The Abbe Intieri and The Marquess of Rinuccini and included more distribution of knowledge in a treatise on the productive power of industry, money and exchange, gold and silver, commerce, and trade. At first, the science of political economy in France was considered only in its application to public finance4.

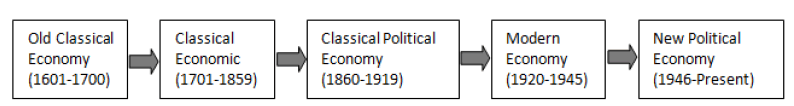

As a result of research from many studies of the literature, the flow of political economy’s history could be depicted as in Figure 1. Obviously, the first discussion about the Merchantilsm’s System of political economy dates from 17th Century and is called an Old Classical Economy. After that, the Classical Economic5 phase appeared between 17th Century and 18th Century. It then moves on to Classical Political Economy phase. Then, from 1920 until 1945 what is called the Modern Economy6 phase occurred after the First World War. Following this, the new face for the new generations was called the New Political Economy phase, also called Modern Capitalism, which saw reconstruction and the new developments in the country post the Second World War. Vernby (2006) in his dissertation states:

“Some authors have called ‘new political economy’ (Drazen, 2000; Saint-Paul, 2000b), others ‘modern political economy’ (Frieden, 1991; Banks & Hanushek, 1995), and yet others ‘comparative political economy’ (Levi, 2000; Alt, 2002) or ‘positive political economy’ (Alt & Shepsle, 1990)”.

The five phases, with the different scholars who figured in each phase, are shown in Table 1. From Table 1, it can be seen that the history of political economy discourse started from 17th Century in France with the development of economic theory from the Mercantilism system. It is a first in the knowledge on political economy (Cole, Cameron, & Edwards, 1991). However, Say, Prinsep, and Biddle (1827) claim that the knowledge of the political economy did not grow in France, but rather in Spain where discourses on political economy were delivered. They give examples such as Alvarez Osorio and Martnez-de-mata, Moncada, Navarette, Ustaritz, Ward and Ulloa writing on The Patriotism of Campomanes.

We can capture the country from the history of the political economy discourses and conclude that certainly it came first from France. There were six famous scholars from France discussing the political economy: Montchrestien (1615) in the Old Classical Economic phase; Montesquieu (1748), Quesnay (1758) and De Verri and Beccaria (1771) in the Classical Economics phase spearheading Mercantilism ideology; and Walras (1899) and Say (1880) in the Classical Political Economy phase. Each scholar published a book which is still prominent in current political economy ideas.

Montchrestien (1615) published a book related to the scope of political economy entitled Traicté de l'économie politique (Trait of The Political Economy). Through the book, he was influencing other scholars of the Mercantilism system which should be called the old classical economics. He writes more on the value of productive labour use and wealth acquisition in promoting political stability. Originally from France he had been a French soldier, dramatist, adventurer and economist who came to be a political economy figure a long time ago.

He was followed by Montesquieu (1748), also from France, recognised as a political philosopher who published a book entitled The Spirit of Law which discussed political economy focusing on the law. Distinct from Montchrestien (1615), Montesquieu (1748) was one of the greatest philosophers of liberalism which formed Classical Liberalism ideology. The content of the book focused more on the forming of government such as separation of state powers like executive, legislative, and judicial; classification of systems of government based on their principles; considering laws on all national wealth related to the state of debt; reflections on commerce and virtue in the Persian letters. He also discussed religion which aims at the perfection of the individual; and civil laws aimed at the welfare of society. Andrew Scott Bibby (2016) wrote a book entitled Montesquieu’s Political Economy which states that Montesquieu’s ideological view, whether as Economic Liberalism or Economic Freedom, was forming the Classical Liberalism, whether in politics or economics.

Scholars in the 17th Century were focused on Neo-Mercantilism with their new strategies that encouraged exports, discouraged imports, controlled capital movement and centralized currency decisions in the hands of a central government. The aim of Neo-Mercantilism was to ensure the preference for countries in Europe for economic growth.

The objective of Neo-Mercantilism is to increase the level of foreign reserves held by government, allowing more effective monetary policy and fiscal policy. This relates to three subjects mentioned by De Verri and Beccaria (1771) in Verri's Economic Theory, which concentrates on prices, aggregate equilibrium and distribution. This parallels a book entitled Reflection's on Political Economy. With experience as an economist, historian, philosopher and writer, he discusses the regulation of production and consumption of wealth to increase national power, strength and happiness. All of these are achievable through an increased population, incentives for labour, increased production and an appropriate balance between it and consumption. In 1780, the discussion was influencing Filangieri, an Italian jurist and philosopher who, following the principles of de Verri, wrote a book entitled Treatise on Politics and Economics of Law (Maestro, 1976).

The Mercantilism school of thought was represented by Stuart (1767) a Scottish economist who was presenting his ideas in his book, An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, with a moderate Mercantilism perspective. This school of thought held that a positive balance of trade was of primary importance for any nation and required a ban on the export of gold and silver. This theory led to high protective tariffs to maximize the use of domestic resources, colonial expansion and exclusivity of trade with those colonies. Stuart (1767) held that profit was a mere surcharge upon alienation (sale) of the commodity.

Quesnay (1758) held the physiocratic7 as his school of thought, distinct from the Mercantilism and classical liberalism8 of Montchrestien (1615) and Montesquieu. Quesnay (1758) in his Economic Table (Tableu Economique) mentioned the importance of economist-laws in wealth and agriculture to the welfare of a nation as well as illustrating his own political support for constitutional oriental despotism9.

Almost 100 years after the Mercantilism era, Walras (1899) and Say (1880) came to the classical political economic ideas (1860-1919). Walras (1899) wrote a book entitled Leon Walras’s Elements of Pure Political Economics (Leon Walras’s Elements D’economic Politique Pure). As a French Mathematical Economist and Georgist, influenced by economist and sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, he supplied the origin of marginalist economics and formulated the marginal theory of value (independently of Jevons (1871) and Menger (1871)) and pioneered the development of general equilibrium theory.

Say (1880) as a French economist and businessman published the book entitled Treaties of Political Economy. He was influenced by Adam Smith and classical liberalism which discussed production, distribution and consumption of wealth, favouring competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. From this, Friedman (1962) in the New Political Economy phase, also influenced this ideology which struggled to spread outside the capitalism and freedom ideology as discussed by Smith (1776), Mill (1848) and Fisher (1906), who advocated free trade, smaller government and a slow, steady increase of the money supply in a growing economy and monetarism10.

In the phase of classical economics, a famous scholar from Geneva, Rousseau (1755), published an article on Discourse on Political Economy and his famous book The Social Contract was published on 1762. These are cornerstones in modern political and social thought during the enlightenment throughout Europe. Rousseau (1755) claimed that the state of nature was a primitive condition without law or morality, which human beings left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation.

After Neo-Mercantilism ideology or moderate Mercantilism, the new ideology capitalist scholars appeared, such as Smith (1776) in the United Kingdom who cultivated a new perspective in Economic Development. Smith (1776) was educated in Scotland and recognised that a national economic policy was built to maximize the exports of a nation. He promoted government regulation of a nation’s economy for the purpose of augmenting state power at the expense of rival national powers. Power to the market was also discussed in his book entitled The Wealth of Nation where he described the economic with a politic perspective. Freedom in the market was revealed in the theory of value. From this discussion, he was recommended by political economy scholars (Cole, Cameron, & Edwards, 1991). So many scholars, historians, and philosophers were produced from Smith (1776) who became a celebrity with the publication of the book entitled Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Say, 1880)11.

Marcet (1816), one of scholars who followed Adam Smith, published his book entitled Conversations on Political Economy which explained the ideas of three of the scholars in this school of thought: Adam Smith, Ricardo and Malthus. Besides Malthus (1820)12, Ricardo (1817)13 also is a British political economist and scholar who was influenced by Smith (1776). He advanced a labour theory of value and contributed to the development of theories of rent, wages, and profits. Although they are in the same stream of thought, Malthus (1820) still rebuts Ricardo’s (1817) work particularly rejecting the idea developed by Say (1880) that theorizes that supply generates its own demand. Malthus (1820) argues that the economy tends to move towards recessions because productivity often grows more quickly than demand.

After the death of David Ricardo in 1823, McCulloch (1825; 1845; 1870)14 with his physiocratic ideology was widely regarded as the leader of the Ricardian School of Economist. He wrote the book, Outlines of Political Economy which focused more on production, distribution and consumption of wealth; the science of the laws; and public and private wealth affairs. Thus, the ideology of physiocratic onward influenced Fawcett (1883), a British economist and statesman, who became a Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge in 1863. In the political economy field he published the book entitled Manual of Political Economy.

Following the school of thought of Smith (1776), Bentham (1843) published a book with the same title as Fawcett (1883), namely The Manual of Political Economy with one new idea as the founder of Modern Utilitarianism15. He was more aware of welfare economics related to the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship, and other matters that form the content of modern income and employment. Besides that, Bentham (1843) also discussed monetary economics and monetary expansions, continued by Fisher (1906) in the Modern Economic phase and Friedman (1962) in the New Political Economy phase. From that, Bentham (1843) founded the Laissez-fair Principle which influenced the Liberty ideology. This was followed by Mill (1848) who published Principles of Political Economy which focused on answering unsettled questions relating to political economy proposed by Bentham (1843) particularly tax, commodity and debt into government.

Progress of knowledge on political economy developed by Bentham (1843) and Mill (1848) continued with ideas on marginalist economics (marginal utility16) which were discussed by Jevon (1871), Menger (1871) and Walras (1899). Utilitarianism ideas, influenced by Bentham (1843) and Mill (1848), formed the idea of marginal utility. Simultaneously, Jevon (1871) and Walras (1899) discussed more on the theory on value and Menger (1871) discussed more on marginal utility of goods. Besides that, Walras (1899) was a pioneer in the development of general equilibrium theory.

Jevon’s (1871) legacy of marginal utility seems to have influenced Marshall (1890) who was a founder of Neo-Classical Economics17 and published a book entitled Principles of Economics. This brings to the ideas of supply and demand the adjustment of consumption until marginal utility equals the price (price elasticity of demand).

Beside marginal utility ideas, Neo-Classical Economy is used by many scholars in this phase. One of them is Fisher (1906) whose most popular books were The Nature of Capital and Income and The Theory of Interest. He was one of the earliest American neo-classical economists. He focused more on debt-deflation, capital, capital budgeting, credit markets, and the factors (including inflation) that determine interest rates.

Four scholars developed theories distinct from the foregoing discussions: J. N. Keynes (1891), Veblen (1899), Pareto (1906), and J. M. Keynes (1936). J. N. Keynes (1891) wrote a book entitled The Scope and Method of Political Economy recognised in positive economy, normative economy and applied economics. The art of economics relates the lessons learned in positive economics to the normative goals determined in normative economics. He tried to synthesis deductive and inductive reasoning as a solution to the “Methodenstreit”.

Veblen (1899) a Norwegian American economist, in his book The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions discussed Marxist ideology and pragmatism and was critical of capitalism. He discussed cost of production theory, conspicuous consumption and Veblenian dichotomy.

Then, Pareto (1906) in his book of Manual of Political Economy, influenced by Walras (1899), recognised microeconomics, socioeconomics, Pareto-optimality and cardinal utility. The focus is on equilibrium in terms of solutions to individual problems of objectives and constraints. Finally, J. M. Keynes (1936)18 published the book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. In the Modern Economic phase this continued post war macroeconomics utilizing Malthus’s ideas and bringing new ideas which fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments.

| Table 1 Streamline of the Capitalist’s World History on the Political Economy Thought |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centuries | 17th Century | 18th Century | 19th Century | 20th Century |

| Phases | Old Classical Economy (1601-1700) | Classical Economy (1701-1859) | Classical Economy (1701-1859)àClassical Political Economy (1860-1919) | Modern Economy (1920-1945)à New Political Economy (1946-Present) |

| Ideologies | Mercantilism | MercantilismàClassical Liberalism | Classical Economy/Classical Liberalism | Neo-Classical Economy (Henry, 1990) |

| Scholars | Montchrestion (1615):France | Montesquieu (1748): France | Smith’s Classical Liberal: Marcet (1816): British | Neo-Classical Economy: Fisher (1906): American |

| Rousseau (1755): Geneva | Smith’s Classical Liberal: Ricardo (1817): British | Cardinal Utility: Pareto (1906): Italy | ||

| Stuart (1767): Scotland | Smith’s Classical Liberal: Malthus (1820): British | Macroeconomics: Keynes (1936): British | ||

| Moderate Mercantilism/Neo-Mercantilism: De Veri & Beccaria (1771): France à Filangieri (1780) | Utilitarianism: Bentham (1843): Britishà Jevon (1871): British, Menger (1871): British, Walras (1899): Franceà Marshal (1890): British (Applied Economics) | Liberal Capitalism: Friedman (1962): American | ||

| Classical Liberal: Smith (1776): Scotland | Laissez-Fair Principle: Bentham (1843): BritishàMill (1848): British | Cole, Cameron & Edwards (1991) & Etc. | ||

| Physiocracy: Quesnay (1758): France | Quesnay’s Physiocracy: Ramsay (1825): ScotlandàFawcett (1883): British | |||

| Peshine (1853): United States | ||||

| Classical Liberalism: Say (1880): France | ||||

| Keynes (1891): British | ||||

| Pragmatisme: Veblen (1899): Norway American | ||||

Based on the Table 1, from foregoing discussions it can be concluded that over four centuries there were five phases incorporating the theories of known capitalist’s political economy scholars. Firstly, the early political economy discussion, Old Classical Economy, started in the 17th Century and was spearheaded by Montchrestion (1615) from France in Mercantilism ideology. In the 18th Century, Classical Economy continued the Mercantilism ideology with Montesquieu (1748) based in France, followed by Rousseau (1755) from Geneva and Stuart (1767) from Scotland. Afterward, De Veri and Beccaria (1771) from France and Filangieri (1780) constructed the Moderate Mercantilism or Neo-Mercantilism ideology. At the same century also, two different ideologies developed, with Mercantilism by Smith (1776) from Scotland recognised in Classical Liberalism and Quesnay (1758) from France recognised in Physiocracy.

Then, in the 19th Century, Classical Economy or Classical Liberalism ideology developed between 1816 and 1900, with Marcet (1816), Ricardo (1817) and Malthus (1820) from Britain taking the Smith (1776) approach to their studies which was continued by Say (1880) from France who is more recognised in Classical Liberalism. Utilitarianism ideology was developed by Bentham (1843) based in Britain and continued by Jevon (1871) and Menger (1871) from Britain and Walras (1899) from France with Marginal Utility. Marshall (1890) from Britain also studied the Utilitarianism perspective as well as introducing Applied Economics. Other ideologies from Bentham (1843) and Mill (1848), both based at Britain, founded the Laissez-Fair Principle. From the other side, Quesnay’s Physiocracy ideology was attracting the attention of Ramsay (1825) from Scotland and Fawcett (1883) from Britain to execute deep study on the theory. Veblen (1899) a Norwegian American based in Norway held the Pragmatism ideology while Peshine (1853) based in the United States and Keynes (1891) based in Britain worked more on Classical Political Economy and some of the preliminary discussion to Modern Economy.

After the 19th Century, the Modern Economy phase (1920-1945) was followed by the New Political Economy (1946-Present) (Henry, 1990) which was introduced in the 20th Century. In this century, discussion of the Neo-Classical Economy was pioneered by Fisher (1906) from America and continued with the Cardinal Utility Theory by Pareto (1906) based in Italy. Keynes (1936), originally from Britain introduced Macroeconomics and Friedman (1962), originally from America, built on Liberal Capitalism ideology. Cole, Cameron and Edwards (1991) and other scholars in this new phase called New Political Economy continued what was discussed before from other scholars, moving forward to some studies in finance.

Conclusion

All of these discussions could be streamlined over four centuries, from the 17th Century until the 20th Century. Five phases from Old Classical Economy until New Political Economy would describe all of the world history beginning with Mercantilism’s ideology through to New Classical Economy’s ideology. A total of 29 famous scholars were chosen to be represented in this study to give the big picture overview of the world history of political economy thought in Capitalism.

Specifically, most of those describing political economy thought are from the economics field. More could be found from the economic perspective on the capitalist’s world history of political economy thought. Mercantilism is an economic system from 17th Century Europe to increase a nation’s wealth by government regulation of all the nation’s commercial interests. For instance, Cole, Cameron, and Edwards (1991) were concerned with inward reflections from Smith (1776) and Ricardo’s (1817) perspectives as economists. From Ricardo’s (1817) perspective, the preference is for capitalism, landlords and stagnation to be discussed from economic perspective due to economic depression such as free-trade policy, value-price problem and the Ricardian inheritance.

Keynes (1936) perspective includes cost-of-production theory of a whole economy and large corporations. The last preference to be discussed in the study is political practice and economic theory for the real observer in political economy. Pareto (1906) in his study gave his preferences for income distribution in society as a whole; individuals may find the political-economic equilibrium far from optimal, even if both exercising of political power and redistribution absorb no economic resources. Second, and more important, the political process by which economic policy is chosen will generally absorb resources in one way or another, leading to an economically inefficient outcome.

Acknowledgement

Corresponding Author: Dr. Mohd Syakir Mohd Rosdi is a Senior Lecturer at the Center for Islamic Development Management Studies (ISDEV), Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia. This article was been completed while he as a visiting academic and a postdoctoral fellow at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies,

University of Otago, New Zealand from November 2018 until September 2019. Great appreciation to the Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia was supporting me as the co-host of a postdoctoral fellow at National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies capability in realisation of this article. This research was supported by a Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), Malaysia Education Ministry, themed Model Eko-Politinomik Islam (FRGS/1/2018/SSI12/USM/02/1) and USM reference numbers 203/CISDEV/6711711. The submitted article was part of an in-depth research relevant to the grant.

Huge appreciation to Prof. Dr. Richard Jackson Director of National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies due to provide me the place at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago, New Zealand and supervise me towards the realisation of this article.

Endnotes

- Wealth management is an investment advisory service for high net worth individuals (https://investinganswers.com/dictionary/w/wealth-management).

- Jean Baptiste Say (1827) mentioned that, “Algarotti whose writings on other subjects Voltaire has made known, wrote also upon the science of political economy”.

- Jean Baptiste Say (1827) noted that, “In 1764, Genovesi commenced a course of public lectures on political economy, in the chair founded at Naples by the care of the highly esteemed and learned Intieri. In consequence of this example, other professorships of political economy were afterwards established at Milan, and more recently in most of the universities in Germany and Russia”.

- Quality of public finances (QPF) is a concept with many dimensions. It can be viewed as encompassing all arrangements and operations of fiscal policy that support the macroeconomic goals of fiscal policy, in particular long-term economic growth (Barrios, Pench & Schaechter, 2009:8). A crucial objective of the analysis is to understand the impact of government expenditures, regulations, taxes, and borrowing on incentives to work, invest, and spend income. This text develops principles for understanding the role of government in the economy and its impact on resource use and the well-being of citizens (Hyman, 2014).

- The classical economists were able to provide an account of the broad forces that influence economic growth and of the mechanisms underlying the growth process (Hariss, 2008).

- Modern economic theory argues that the fundamentals are not the only “deep” determinants of economic outcomes (Hoff & Stiglitz, 1999).

- Understandings of and commentaries upon production as a means-ends activity are formulated in all societies. Such reflexive statements contain the meaning of the instrumental; and they are formulations of the cultural logic whereby means are transformed to ends. The theory of the Physio- crats, a forerunner of our modern ideas about the economy, is here ana- lyzed as an irreducible production commentary, a structural homemade model [economics, structuralism, history, Western societies] (Gudeman, 1980: 240).

- Butler (2015) mentioned that classical liberalism is the priority they give to individual freedom should aim to maximise the freedom that individuals enjoy.

- Oriental despotism remained The Classical Roots of a Eurocentric Concept. Oriental despotism is deeply rooted in Greek thought where this concept became an effective tool of automatic recognition of Greek identity and superiority over other “barbarous” nations, mainly the great Persian enemy (Minuti, 2012).

- Monetarism is an economic theory that says the money supply is the most important driver of economic growth. As the money supply increases, people demand more. Factories produce more, creating new jobs (Bailey, 2018; Amadeo, 2018).

- It was earlier finding about political economy discourse, Adam Smith and Karl Marx was known in political economy’s scholar. For that, to get the history of political economy we can find from two section is called for Smith Political Economy and Marxist Political Economy (Wang, 1977).

- Malthus (1820) published book with title Principles of Political Economy.

- Ricardo (1817) published book entitled Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

- McCulloch (1825) was appointed the first professor of political economy at University College London.

- Bennett, J. (2005) noted that from John Stuart Mill mentioned that utilitarianism is a perspective which giving entitlement of human being to desirable of peoples without deny on morals.

- Marginal utility is a measurement of happiness while consume the things. In economics, happiness could be measure by additional of money when used are things, otherwise additional hour of works could be decrease level of happiness which be called disutility (Layard, Mayraz & Nickell, 2008).

- Morgan, J. (2016) and Henry (1990). Dissolution of the labour theory of value and the rise to dominance of utility.

- A British economist; The Political Economy Club was founded in 1909 by John Maynard Keynes at King College, Cambridge (Keynes, 1936).

References

Amadeo, K. (2018). Monetarism explained with examples, role of Milton Friedma.

Amemiya, T. (2004). “The economic ideas of classical Athens”. The Kyoto Economic Review, 73(2) (155). 57-74.

Bailey, D. (2018). “Re-thinking the fiscal and monetary political economy of the green state”, New Political Economy.

Baran, P.A. (1957). The political economy of growth, (Ed.) (1973), Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Barrios, S., Pench, L.R., & Schaechter, A. (2009). The quality of public finances and economic growth, Proceedings to the Annual Workshop on Public Finances (Brussels, 28 November 2008). European Commission. Google Books.

Bennett, J. (2005). Utilitarianism John Stuart Mill, (T.T.). Last amended: April 2008. Google Books.

Bentham, J. (1793). A manual of political economy. In, Jeremy Bentham’s economic writings, (Ed.) Stark, W. (1952). London: George Allen & Unwin.

Bentham, J. (1843). A manual of political economy. McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought.

Bibby, A.S. (2016). Montesquieu’s political economy. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Google Books.

Bibby, A.S. (2016). Montesquieu’s political economy. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. Google Books.

Bridel, P. (1987). “Montchrétien, Antoyne de”, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 3(546). 546-47.

Butler, E. (2015). Classical liberalism premier. London: The Institute of Economic Affairs. Google Books.

Cameron, G. (2008). “Oikos and economy: The greek legacy in economic thought”, PhaenEx, 3(1). (spring/summer 2008). 112-133.

Caporaso, J.A., & Levine, D.P. (1993). Theories of political economy, UK: Cambridge University Press. Google Books.

Chisholm, H. ed. (1911a). “Montchrétien, Antoine de”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 (11th Ed.). Cambridge University Press. 762.

Chisholm, H. (Ed.) (1911b). “Quesnay, François”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 (11th Ed.). Cambridge University Press, 742–743.

Cole, K., Cameron, J., & Edwards, C. (1991). Why economist disagree: The political economy of economics. 2nd Ed. London: Longman Group UK Limited.

Dalley, L.L. (2015). On Martineau's illustrations of political economy, 1832–34, Britain, Representation: BRANCH.

Dobb, M.H. (1937). Political economy and capitalism, London: Routledge.

Engels, F. (1859). Karl Marx’s ‘a contribution to the critique of political economy’, Berlin: Das Volk. In Marx.

Fawcett, H. (1883). Manual of political economy, London: Macmillan and Co.

Fisher, I. (1906). The Nature of Capital and Income, London: Macmillan. Google Books.

Friedman, M. (2002). Capitalism and freedom (40th anniversary ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 182–189.

Groenewegen, P.D. (1985). “Professor Arndt on political economy: A comment”, Economic Record, 61, 744–751.

Gudeman, S.F. (1980). Physiocracy: a natural economics, Arlington, Virginia: The American Anthropological Association.

Harris, D.J. (2008). Classical growth model, in, Palgrave Macmillan (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Henry, J.F. (1990). The making of neoclassical economy, New York: Routledge. Google Books.

Hoff, K., & Stiglitz, J.E. (1999). Modern economic theory and development, This paper was presented at the Northeast Universities Development Conference at Harvard University in October 1999.

Hyman, D.A. (2014). Public finance: A contemporary application of theory to policy, USA: Cangage Learning. Google Books.

Jevons, W.S. (1871). The Theory of Political Economy, Revised Book (2013). London: Bibliobazaar, LLC. Google Books.

Jevons, W.S. (1879). The theory of political economy, (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan; Preface in 4th ed., London, (1910). .

Jevons, W.S. (1905). Principles of economics, London: Macmillan.

Keynes, J.M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money, New Published (2018). Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Google Books.

Keynes, J.N. (1891). The scope and method political economy, London: Macmillan and Co. Google Books.

Layard, R., Mayraz, G., & Nickell, S. (2008). “The marginal utility of income”, Journal of Public Economics, 92(Issues 8-9). 1846-1857.

M’vickar, A.M.J. (1825). Outlines of Political Economy, New York: Wilder & Campbell, Broadway. Google Books.

MacLeod, H.D. (1875). “What is political economy?”, Contemporary Review, (25). 871-893.

Maestro, M. (1976). “Gaetano Filangieri and His Science of Legislation”. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 66(6). 1-76.

Maestro, M. (1976). “Gaetano Filangieri and His Science of Legislation”, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 66(6). 1-76.

Malthus, T.R. (1820). The Principles of Political Economy, London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street. Google Books.

Marcet, J.H. (1827). Conversations on political economy, London: Longman, Refs. Google Books.

Marcet, J.H. (1816). Conversations on political economy, London: Longman. Google Books.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of economics, London: Macmillan. Co. Google Books.

Marx, K. (1859). A contribution to the critique of political economy, Introduction by M. Dobb. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1971. Google Books.

Marx, K. (1987). Outlines of the critique of political economy, contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: 29. New York: International Publishers. Google Books.

McCulloch, J.R. (1825a). Outlines of political economy, New York: Wilder [and] Campbell. Google Books.

McCulloch, J.R. (1845). The literature of political economy: A classified catalogue, London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. Google Books.

McCulloch, J.R. (1870). Principles of political economy with sketch of the rise and progress of the science, London: Murray. Google Books.

Menger, C. (1871). Principles of Economics: First General Part. (Trans. & ed.)

Dingwall, J., & Hoselitz, B.F. (1950). New York: New York University Press.

Menger, C. (1871). The Principles of economics, (Ed.) Omkar Bahiwal. (t.t.). Google Books.

Mill, J. (1820). Elements of political economy, (3rd ed.). London, 1926. Reprinted in Mill, James. Selected writings, (Ed.) Wisen, D. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd for the Scottish Economic Society, 1966.

Mill, J.S. (1848). Principles of political economy with some of their applications to social philosophy, in, Collected works of John Stuart Mill. (Ed.) Robson, J. M. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965.

Mill, J.S. (1885). The principles of political economy, New York: D. Appleton And Company. Google Books.

Minuti, R. (2012). “The concept of ‘Oriental Despotism’ from Aristotle to Marx”, EGO: Journal of European History Online.

Mishan, E.J. (1982). Introduction to political economy, London: Hutchinson.

Mohd Rosdi, M.S. (2014). Tahaluf siyasi in Islamic political economy: A theoretical studies, The thesis of Philosophy’s Doctoral was submitted to School of Social Sciences at Universiti Sains Malaysia. Unpublished.

Montchrestien, Antoine de (1615). Traicté de l'oeconomie politique, Geneve: Librairie Droz S.A. Copy right (1999). Google Books.

Montchrestien, Antoine de. (1615). Traicté de l'oeconomie politique, (Ed.) Billacois, F. (1999). Critical-edition preview.

Montesquieu, Baron de. (1748). The spirits of laws, Translate by Thomas Nugent (1752). Canada: Batoche Books. Google Books.

Morgan, J. (2016). What is Neoclassical Economics?: Debating the origins, meaning and significance, New York: Routledge. Google Books.

Pareto, V.F.D. (1906). Manual of Political Economy, (Ed.)

Montesano, A., Zanni, A., Bruni, L., Chipman, J.S., and McLure, M. (2014). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. Google Books.

Quesnay, F. (1894). Tableau Oeconomique, London: Macmillan and Co. Google Books.

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation, London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street. Google Books.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. (1755). Discourse on Political Economy and The Social Contract, Christopher Betts (1994). UK: Oxford University Press. Google Books.

Say, Jean-Baptiste. (1827). A treatise on political economy; or the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth, (Ed.) Biddle, C. C.. (Trans.) Prinsep, C. R. from the 4th ed. of the French, (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1855. 4th-5th ed.).

Say, Jean-Baptiste. (1880). A treatise on political economy or the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth, Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger. Google Books.

Smith, A. (1776). The wealth of nations, (Ed.) 1937, New York: Random House. Google Books.

Smith, A.P. (1853). A manual of political economy, New York: G. P. Putnam & Son. Google Books.

Stigler, G.J. (1976). “The successes and failures of Professor Smith”, Journal of Political Economy, 84(6). 1199–1213.

Torrens, G.F. (2013). Essays on political economy, A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Economics, Washington University in St. Louis. Paper 1082.

Veblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class: An economic study of institutions, (Ed.) (1953). America: New American Library.

Vernby, K. (2006). Essays in political economy, Uppsala: Department of Government, Uppsala University. Google Scholars.

Walras, L. (1899). Éléments d'économie politique pure. (4th ed.; 1926, éd. définitive). In English, Elements of Pure Economics. (Trans.) Jaffé, W. (1954). Google Books.

Wang, G.C. (2018). Fundamentals of political economy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. Google Books.

Received: 09-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21-7737; Editor assigned: 12-Dec-2021; PreQC No. JMIDS-21-7737(PQ); Reviewed: 27-Dec-2021, QC No. JMIDS-21-7737; Revised: 02-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21-7737; Published: 09-Dec-2021