Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 4

Reshape Place Attachment from an Experiential Consumption Perspective: Scale Validation and the Exploration of the Relationship between Place Attachment, Insecurity, and Regulatory Focus

Zhuofan Zhang, Texas A&M University - Kingsville

Ruth Chatelain-Jardon, Texas A&M University - Kingsville

Jose Luis Daniel, Texas A&M University - Kingsville

Citation Information: Zhang, Z., Jardon, R.C., & Daniel, J.L. (2024). Reshape place attachment from an experiential consumption perspective: scale validation and the exploration of the relationship between place attachment, insecurity, and regulatory focus. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(4), 1-19.

Abstract

By developing a unidimensional scale of place attachment, this study investigates the role of place attachment in an experiential consumption context, including its relationship to insecurity and regulatory focus. A series of survey studies were conducted in order to test the reliability and validity of the scale of place attachment. Specifically, Study 1 examined the scale using EFA, CFA, and model fit; Study 2 examined the discriminant and convergent validity of the scale; Study 3 investigated the relationship between place attachment and four types of insecurity; and Study 4 examined the relationship between place attachment and regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention). There is strong reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and nomological validity to the scale of place attachment we developed. In addition, we discovered that place attachment is related to existential insecurity as well as social insecurity, but not to personal insecurity or developmental insecurity. Also, place attachment mediates the relationship between promotion focus, rather than prevention focus, and tourists’ intention to visit a place only when the tourists have developed fondness or strong emotions for it. As a result of the study, we concluded that in order to enhance promotion focus, the promotion ad should describe how the visiting place can assist an individual in accomplishing his or her goals.

Keywords

Place Attachment, Experiential Consumption, Insecurity, Regulatory Focus, Scale Development.

Introduction

The emerging trend in experiential marketing has propelled a wave of research investigating the relationship between tourism-related production and consumption. In particular, following the quarantine that took place during the pandemic, people can be motivated to travel both domestically and internationally to discover the world and reestablish connections with others, to experience a new setting and take a break from their daily routines, etc. In the course of a travel experience, individuals often form a relational tie to a place as a result of affinity (Asseraf and Shoham 2017), engagement (Kumar and Kaushik 2020), symbolic values (Ekinci et al. 2013), memories created (Kim 2014), destination personality (Hultman et al. 2015), among other factors. As stated in previous studies (Enrique Bigne et al. 2008), experiential consumption is characterized by affect and emotion in which consumers experience emotions through interactions with products or services consumed in the tourism and other service industries. Experiential consumption and place of travel are inextricably linked because 1) it is common for people to seek out places to experience as experiences can always take center stage in the course of travel, regardless of the personal or social needs they are seeking to fulfill, such as sensation seeking, establishing ties with social groups, etc. 2) when it comes to marketing a “place” as a product, marketers are generally interested in marketing the engaging and immersive experiences associated with the history, culture, and heritage of the place (e.g., Graziano and Privitera 2020, Tsai 2020). 3) Previous studies have demonstrated that memorable experiences are associated with a higher level of travel satisfaction and a positive word-of-mouth effect (e.g., Triantafillidou and Siomkos 2014, Meng and Han 2018).

As a further point of discussion, previous studies have asserted that the consumption of experiences is dimensionally diverse and encompasses hedonic dimensions, such as emotions and feelings (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982, Jantzen et al. 2012). Experiences of tourists can be separated into several categories including sensations, feelings, and others (Schimitt 1999). As an example, tourism literature has taken a more emotional approach to studying relationship marketing than a rational one (Jantzen et al. 2012). When individuals build strong emotional bonds or have strong attachments to their destination, the experience of destination travel becomes memorable and enjoyable. The use of emotions as a tool for product or brand management is always important. Various studies have shown that brands with strong emotional attachments may have a greater ability to connect with consumers (e.g., Kemp et al. 2014). Moreover, experiential marketing is described as sensory and emotional in nature (Schmitt 1999). Thus, the literature on experiential consumption has explicitly focused on the role of emotions and considered, for example, the effect of attachment to a place on consumers' travel behavior (e.g., Tsai 2016). Specifically, during the process of consuming experiences, a reciprocal relationship occurs between individuals and places in which individuals strengthen emotional bonds and crave maintaining the emotional connection. As event marketing has become increasingly popular in recent years, and consumers visit places not only for their physical properties, but also for the experiences and events they offer (e.g., Wood and Masterman 2008). There has, however, been no emphasis placed on how experiential consumption contributes to feelings and emotional attachments in the previous studies. These experiences extend beyond entertainment, food, local culture, and sports. The primary concern of event and experiential marketers is to ensure that their experiences not only attract consumers, but also increase their retention and emotional attachment to them over time. As a result of the experiences themselves that evoke sensations and excitement, pleasure and joy, consumers will develop a strong emotional attachment to that particular location.

For a comprehensive understanding of place attachment from an experiential perspective, marketing perspectives are required to bring new insights to tourism research as well as the mechanisms by which experiential marketing drives place attachment, its antecedents, outcomes, behavioral intentions, etc. From an experiential perspective, the place of destination is more valuable in terms of its hedonic value rather than its cognitive value such as the ability to form memories. As a result of this new perspective, the experiential perspective can be integrated into a framework of marketing, place branding, and emotional attachment in this study, focusing on the experiential and hedonic value associated with experiences associated with places, as well as certain cognitive factors such as insecurity and regulatory focus, as well as certain factors such as insecurity. It focuses on experiential and hedonic aspects of marketing and experiential consumption as opposed to the tourism perspective, which focuses on the tourism industry and cognitive decision-making process. By way of example, tourist experiences are designed to meet emotional needs, and self-identity or individuals’ “emotional” selves are altered as a result of experiential consumption (Cutler and Carmichael 2010, Jantzen et al. 2012). Based on this novel perspective, marketing and experiential consumption are examined in relation to the complex interaction between hedonic values, experiential consumption, and emotional attachment. Several studies have shown that emotion is an effective indicator of marketing outcomes, and that emotional attachment is associated with a number of other factors, such as tourism brand relationship quality, brand equity, brand engagement (Thomson et al. 2005, Castaneda Garcia et al. 2018, Junaid et al. 2019).

It is therefore the purpose of this study to investigate the role of place attachment in an experiential consumption context. Specifically, the literature review will address the unidimensionality of place attachment as well as how experiential marketing influences this new concept. In the second part of the literature review, we will discuss the antecedents of place attachment and how they fit into a nomological framework that facilitates our understanding of them.

Theory of Place Attachment

In the past, the majority of previous studies investigated and validated the place attachment scale in the areas of person-environmental relationships, geography, environment-related interdisciplinary studies, and so forth. In Brown and Raymond (2007), place attachment scales were examined in relation to landscape values as indicators of place attachment in aesthetics, recreation, economics, spirituality, and therapeutics, and landscape values were found to be appropriate indicators of place attachment when land use management was undertaken. As an explanation for the relationship between rural landholder attachment and natural resources involving both physical and social characteristics, Raymond et al. (2010) used a four-dimensional model involving both physical and social aspects. In addition to contributing to the current environmental psychology literature, Boley et al. (2021) tested an abbreviated place attachment scale within a variety of residential or recreational settings. There has, however, been little research examining how place attachment plays a role through the lens of experiential consumption.

It has been argued that consumer attachment is explained by attachment theory (Bowlby 1979). However, previous studies have argued that place attachment plays an influential role. In Bowlby's (1979) definition, attachment refers to the bond that is established between individuals. Later on, the attachment theory is applied to marketing where individuals develop attachments to objects and products. In previous studies, it has been documented that attachment can occur between individuals as well as between individuals and objects, such as brands, products, etc. (e.g., Thomson et al. 2005). Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated that brand attachment can be explained by a certain type of self-identity that individuals are seeking to fulfill (e.g., Swaminathan et al. 2009, Lee et al. 2015). Basically, anything to which they feel attached is a reflection of their extended self. Moreover, an attached relationship can also be viewed as a reflection of an extended self or extended identity. It is especially true when an individual develops a relationship with something through experience, such as a brand, product, or object, that is based on commitment. There has been, for example, previous research that suggests that consumers’ psychological attachment to brands would increase if they were given symbolic or hedonic values to attach to (e.g., Thomson et al. 2005). The results of previous studies have also suggested that emotional experiences can enhance a consumer’s sense of experience, which in turn would lead to a stronger attachment to a brand (Shahid et al. 2022).

It has been argued in previous studies that the scale of place attachment varies considerably (Boley et al. 2021). There is a consensus among most studies that place attachment is a one-dimensional construct. As a matter of fact, adhering to the original definition of attachment, an emotional and objective relationship between an individual and an object is regarded as a dynamic and impressive attachment. Attachment to a brand is often perceived as emotional rather than cognitive, which differentiates it from other constructs such as trust, commitment, value, and love. In terms of experiential consumption, place attachment should also be viewed as an emotional response when explaining object attachment or brand attachment. According to previous literature, attachment is closely related to other emotional states such as compassion and love (Thomson, et al. 2005), further supporting the idea that attachment is an emotional state. Additionally, place identity differs from place attachment in terms of meaning. According to Peng, Strijker, and Wu (2020), place attachment is more of an emotional or affective response. Consequently, place attachments should be defined in terms of their emotional or affective nature, particularly within experiential consumption contexts where they are hedonic and experiential rather than functional. The concept of place attachment does not include cognitive or behavioral dimensions in the narrow sense (Peng et al., 2020). Based on the above notion, place attachment, in this study, is defined as an emotional or sensorial tie between an individual and a particular place. Considering that a person’s attachment to a place must be formed by traveling, etc. the emotional bond between a person and the place to which he/she is traveling would be reinforced through the travel experiences and the corresponding hedonic consumption experiences. As experiences can be viewed as psychological processes that involves attaching feelings to products and brands (Kuiper and Smit 2014), place attachment would be accumulated as the level of an individual’s experience and experiential consumption increases at a particular place. A theoretical framework can thus be developed to explain the relationship between experiential consumption and place attachment, which also facilitates the exploration of many factors influencing place attachment and the formation of such attachments. Specifically, the current study aims to examine the effect of insecurity, a common negative emotion, on place attachment, as well as the role of regulatory focus in the formation of attachments. To accomplish this goal, Study 1 will examine the scale using EFA, CFA, and model fit; Study 2 will explore the scale’s discriminant and convergent validity; in Study 3, we will examine the relationship between place attachment and four types of insecurity; and study 4 will examine the relationship between place attachment and regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention focused).

Study 1

Study 1 is designed to develop and validate the place attachment scale. On the basis of the theoretical background mentioned above, particularly in an experiential context, the items designed should ensure that they capture the conceptual definition and emotional significance of the construct place attachment. Furthermore, as previously suggested by research, a smaller pool of items was initially developed to tap narrowly defined constructs, as narrowly defined constructs require fewer items (e.g., Jenkins and Griffith 2004), and as long as the items can capture the construct’s essence, fewer items are best. Also, Study 1 utilized both EFA and CFA to test the model fit and ensure that all the items were performing well under the same construct. In addition, the convergent validity of the scale items is examined in order to ensure that the items are all grouped into a single dimension.

A total of 209 participants were recruited from a Qualtrics panel. The average age of the participants is 23.69, with 104 females and 105 males. As part of the study, participants were asked to evaluate the four-item scale of place attachment and to identify the degree of agreement or disagreement with each statement.

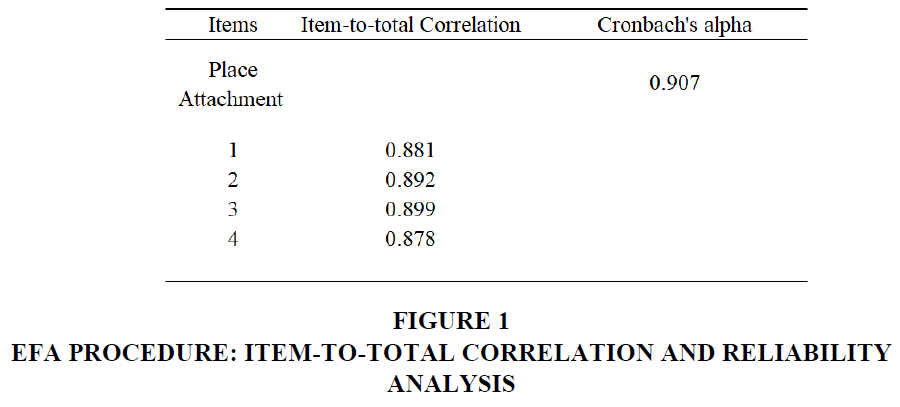

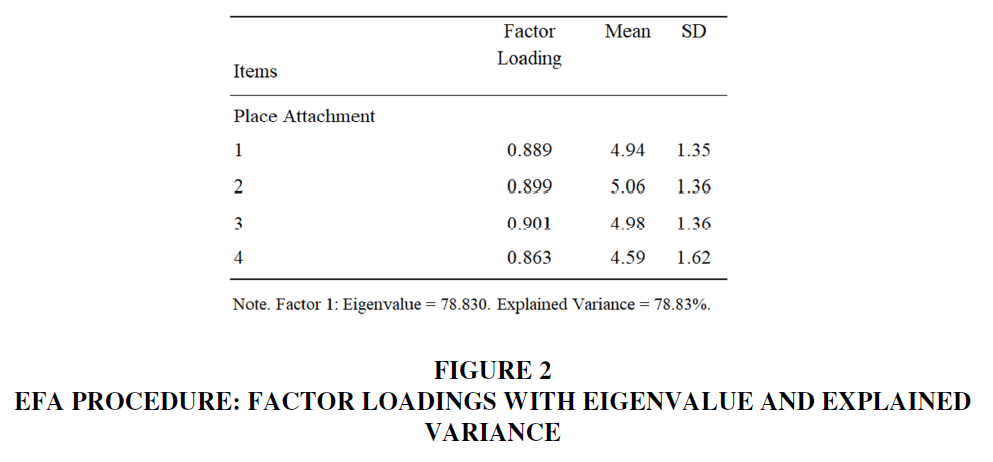

To further perform the exploratory factor analysis, an extraction method of principle component analysis and a rotation method of “oblimin” were chosen. As the results in show, four items of place attachment were correlated well, with high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.907) and factor loadings exceeding .80. The four items together are responsible for 78.83% of the explained variances. Thus, a place attachment scale based on four items was found to be valid and reliable Figure 1-10.

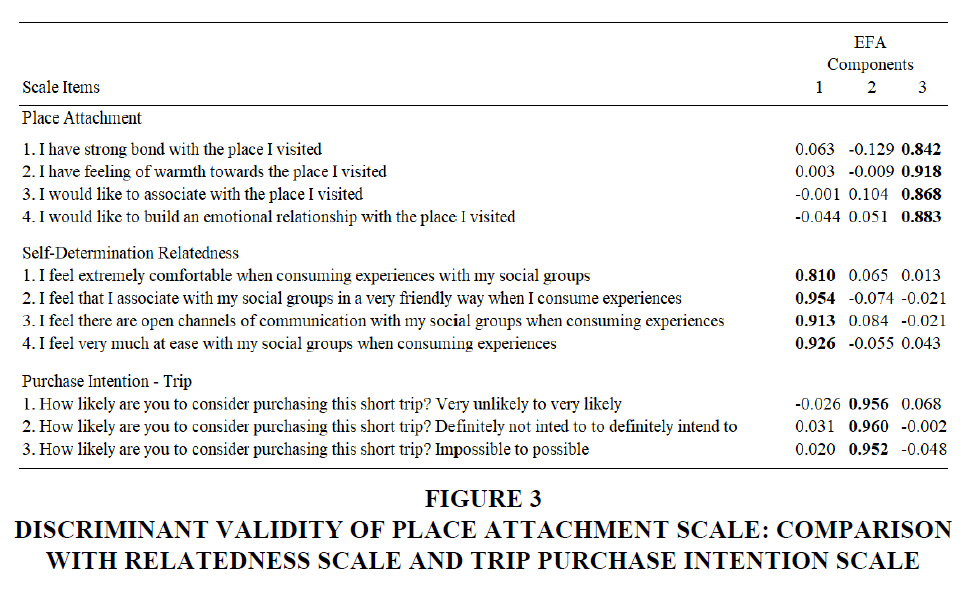

Figure 3 Discriminant Validity of Place Attachment Scale: Comparison with Relatedness Scale and Trip Purchase Intention Scale

Further testing of the scale was conducted using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) involving the same 209 cases. A good fit was found for the one-factor structural model: (χ2= 24.896, degrees of freedom (df) = 3,p < 0.001;normed fit index (NFI) = 0957., comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.962,Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.923; Browne and Cudeck1992, Hu and Bentler 1999, Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Müller 2003).

Convergent validity was tested in several ways. The composite reliability (CR) for the construct was 0.894, which is above the recommended 0.80 threshold (Fornell & Larcker,1981). Second, the average varianace extracted (AVE) score for place attachment variable is 0.678, which exceeds the 0.5 criterion proposed by Bagozzi and Yi (1988). It is evident from the results that the scale items are converged into the same dimension of the construct, which supports convergent validity.

Study 2a

Study 2a aims to test the discriminant validity of the place attachment scale. To validate discriminant validity, place attachment scale was compared with two other scales: one scale was adopted from self-determination – relatedness dimension, as it only measures the relationship need of individuals, which is related but distinct from the concept of attachment; the other scale is the purchase intention, which is typically the behavioral outcome of emotional attachment, as reflected in previous studies (e.g., Fedorikhin et al. 2008) concerning brands, products, and places, and is highly related to yet distinct from place attachment.

A new sample of 143 participants was recruited from Qualtrics panel, with an average age of 24.75 (69 females and 74 males). Participants were asked to rate the four-item place attachment scale, and self-determination-relatedness scale, as well as purchase intention (trip) scale on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”. To evaluate self-determination scale, participants were asked to assess the statements such as “I feel extremely comfortable when consuming experiences with my social groups”; “I feel that I associate with my social groups in a friendly way when I consume experiences”, and so on. To evaluate purchase intention (trip) scale, participants were asked to rate the likelihood of purchasing a short trip by reading the statements such as “how likely are you to purchase a short trip?” from 1 “very unlikely/definitely not intend to/impossible” to 7 “very likely/definitely intend to/possible”, and so forth.

In the following step, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to verify the factor loadings for the three related but distinct constructs. In accordance with, the EFA results revealed that three constructs were loaded with their own factors, with no cross-loading or low loading on any one construct.

Study 2b

The purpose of Study 2b is to further test the nomological validity of the place attachment scale by integrating I with other factors in a nomological network. To test nomological validity, place attachment was theoretically hypothesized to be correlated with insecurity, and the hypothesis was empirically tested. The theoretical reasoning of linking attachment with insecurity is based on previous studies that attachment to a place and insecurity are both expressions of emotion. Essentially, attachment behavior is a person’s nature of retaining physical and emotional proximity to an individual or object (e.g., Hinde 1982) and a strong social tie between individuals developed during early childhood. The literature has shown that if an individual does not establish a strong and healthy attachment in the early stages of his or her development, he or she may feel insecure. As a result, attachment relationships are not limited to parent-child relationships but can also be reflected in other relationships as well, such as romantic relationships, sibling relationships, family relationships, and friend relationships. As a result, an individual's feelings towards individuals or objects reflect his or her intention to belong to a particular social group. Therefore, compensatory behavior may be observed when an individual does not feel secure or attached enough. Alternatively, previous studies have explored several types of attachment, including insecure attachment, and found an association between attachment and insecurity. It is thus suspected that when stimulus of “separation” occurs, individuals would establish insecurity.

In the meantime, marketing literature has extensive research on consumers' methods of alleviating feelings of insecurity through the purchase of goods or brands, engaging in materialistic behavior, etc. As a means of reducing the feeling of negative emotions (e.g., Rindfleisch et al. 2009), consumers seek to develop a strong relationship with the brand by experiencing similar feelings such as attachment to the brand. The accumulation of experiences, similar to the acquisition of physical goods, may also be able to alleviate the insecurity feelings associated with travel of other experiential consumption. It may be possible to postulate that feelings associated with products may contribute to relieving negative feelings when individuals are associating their feelings with a place. As an example, when lacking intimacy in personal relationships, a person would be inclined to associate with a place since a place possesses memories and experiences related to the individual’s identity, and insecurity can be significantly alleviated by forming attachments to that place.

Thus, in order to further explore the relationship between place attachment and insecurity, a study has been conducted with the same sample collected in Study 2a (sample size 143 with an average age of 24.75, 69 females and 74 males). The study utilized the insecurity scales developed by Rindfleisch et al. (2009) which comprise four types: existential insecurity, personal insecurity, social insecurity, and developmental insecurity. Participants were asked to evaluate the four-item place attachment scale and four types of insecurity scales including statements such as “I am concerned about my style of doing things”; “for me, avoiding failure has a greater emotional impact than the emotional impact of achieving success” on a 7-point Likert scale with 1 “strongly disagree” and 7 “strongly agree”.

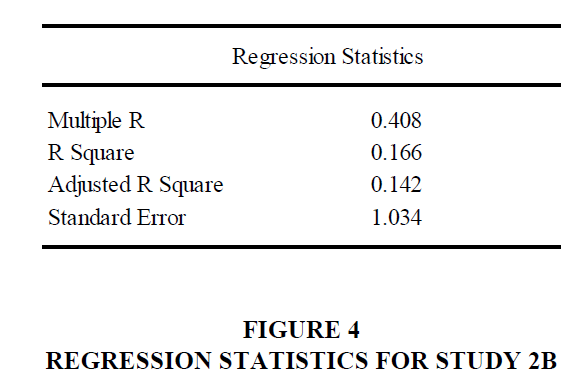

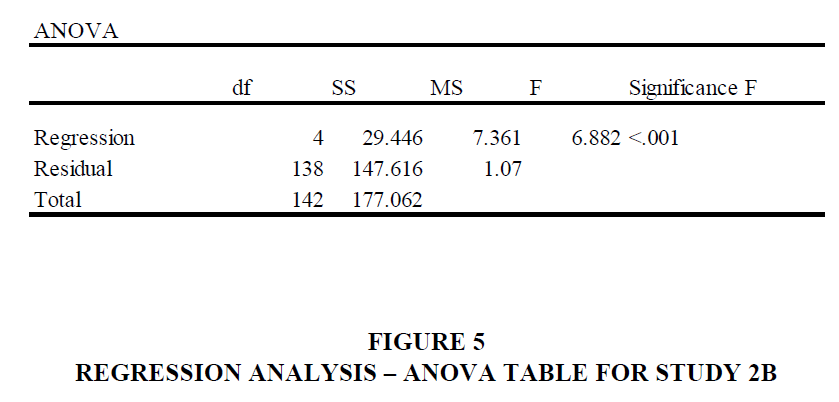

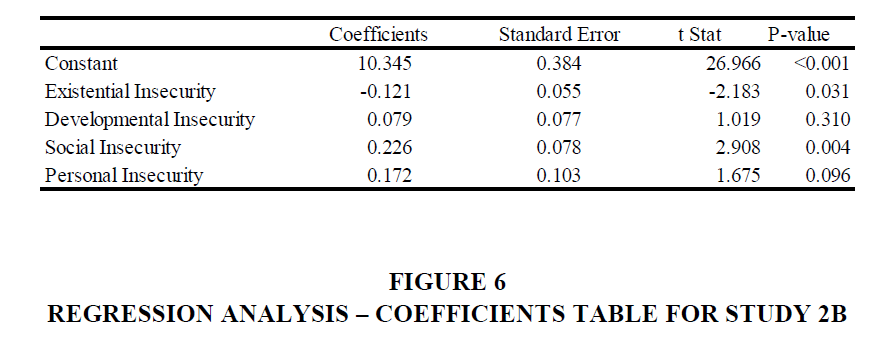

As a next step, a regression analysis was carried out, in which place attachment was regarded as the dependent variable and four kinds of insecurity were regarded as the independent variables. The results showed that only social insecurity (B = 0.226, p < 0.01) and existential insecurity (B = -0.121, p < 0.05) are significantly associated with place attachment. The relationship between social insecurity and place attachment can be attributed to the fact that experiential tours of visiting a place are typically accompanied by social groups, such as participating in leisure activities with friends at the destination. Individuals can develop social bonding as an important component of their social lives through traveling experiences together. Also, individuals who have close relationships with their social groups enjoy a sense of belonging and support when traveling together. On the other hand, individuals who experience existential insecurity are generally unsure of the meaning or purpose of their life. A travel experience is generally considered hedonic and involves a greater number of intrinsic goals than extrinsic goals. It is intended to make individuals feel the meaning of life and achieve self-fulfillment or self-actualization through the experience of visiting a place. Furthermore, the experience of visiting a place can lead a person to wonder about the meaning or purpose of life, since it involves autonomy motives that enable a person to take charge of his or her own life, and the connection to the place can assist the individual in fulfilling their intrinsic needs to reach psychological well-being. As a result, the experience of visiting a place and forming an emotional attachment to a place may alleviate the individual’s initial feeling of existential insecurity, as the findings of this study suggest. In accordance with the self-determination theory, the results of this study suggest that existential insecurity, which is related to a person’s “sense of being alive”, and social insecurity, which is associated with a person’s “sense of belonging”, are closely related to place attachment. Thus, place attachment may serve as a way of resolving the emotional stress associated with fulfilling basic psychological needs such as autonomy and relatedness.

Study 3

The purpose of Study 3 is to test the relationship between place attachment and the common cognitive factors in a nomological network in order to further validate the nomological validity of the scale. The rationale for investigating whether place attachment, which is emotional, is related to cognitive factors is as follows: experience-based consumption is a complex and diverse process that is influenced by a variety of factors. As part of this framework of place attachment, it is pertinent to integrate cognitive factors as well as determine that regulatory focus plays an instrumental role. There has been no examination of the effect of place attachment focus in combination on behavioral intentions, such as purchase intentions, in previous studies. When it comes to experiential consumption, place attachment represents the emotional component of a relationship between a person and a place, while regulatory focus factors represent the cognitive component. Therefore, it is unknown the effect of these factors when it comes to purchasing intentions of experiences, such as visiting intentions of a place, though it is worthwhile and significant to investigate them. It has been shown previously that intrinsically motivated individuals possess positive emotions (e.g., Lovoll et al. 2017, Silvia and Kashdan 2009), which potentially indicate a correlation between emotional attachment and intrinsic motivation.

On the other hand, the regulatory focus theory is concerned with the attachment to goals and the motivations that motivate them. Those oriented toward promotion prefer to approach goals than abstain from them. They also aim for growth and development. While prevention-oriented individuals are concerned with avoiding potential or undesired outcomes. Literature has demonstrated that individuals with high attachment tend to pursue their experiential goals with greater vigor. In addition to exploring their surroundings or attending events, they view experiences as gains. However, prevention is more closely related to safety and security, which means consumers, would prefer to restrict individuals from participating in experiential activities. In addition, experiences relate to one's hobbies, entertainment, activities, interests, etc., which are more promotional in nature. A previous study suggests that individuals are more inclined to promote their hobbies and interests when related to their hobbies and interests. Moreover, emotional attachment may be viewed as a means of advancing the relationship between consumers and places, which is also an advancement-related focus. Consequently, we expected to see that people with high place attachments are interested in advancing their experiences in a promotional manner.

Furthermore, motivating oneself is imperative because it is able to connect emotions to cognitive motives and goals. For marketers, emotions play a crucial role in determining the marketing outcomes they wish to achieve and in employing the appropriate strategies to achieve those goals. However, are motivational tendencies, such as promotion focus, conducive to behavioral intentions without emotional attachment? As a result, individuals may consistently demonstrate strong intentions to achieve certain outcomes without forming an emotional connection or establishing an emotional attachment. The underlying mechanism is that emotional attachment is characterized by greater vulnerability and sensitivity, which constitutes and emotional driving force that affects human behavior, while promotion focus involves a strong cognitive determination to motivate a person to achieve life goals. Additionally, feeling attached improves a person’s sense of security and safety, which is closely related to the person’s desire to prevent loss, such as deprivation, rather than achieve something in the first place. Therefore, it is hypothesized that individuals with a promotion focus are less influenced by their emotional state, such as attachment, and may be motivated to act in a way to achieve a particular outcome regardless of their feelings.

Thus, the purpose of study 3 is to investigate the relationship between regulatory focus factors and place attachment in a nomological network. An estimated 420 respondents (113 males and 307 females, mean age 43.34) were collected from a Qualtrics panel. Each participant was informed that they will be evaluating a place of their choice. Participants were randomly assigned to two scenarios: one group was asked to list a place that they love, while the other group was asked to list a place they do not love at all. It was our expectation that regulatory focus factors would have a significant effect only on the behavioral intentions of the participants when they form certain emotions, such as love. Upon evaluating the scenario, participants were asked to complete several measures, including the one/five/ten/twenty year visiting intention scale, the place attachment scale we developed in study 1 and 2, and the regulatory focus scale (promotion vs. prevention). In order to measure the visiting invention, we asked participants “how likely is it that you will be visiting this place 1 year / 5 years / 10 years / 20 years from now?” on a 7-point likert scale from “very unlikely/definitely not intend to/impossible” to “very likely/definitely intend to/possible”. For place attachment scale, we used the four-item scale of place attachment we developed and validated in the study 1 and 2, by incorporating the statements such as “I have a strong bond with the place I visited / I have a strong bond with the place I visited / I would like to associate with the place I visited / I would like to build an emotional relationship with the place I visited” and ask participants to evaluate the scale items on a 7-point Likert scale from “1 strongly disagree” to “7 strongly agree”. For the regulatory focus scale, we cited the items from Lockwood et al. (2002), which includes the measures of both promotion and prevention focus factors. For the prevention focus factor, we included the statements such as “I am anxious that I will fall short of my responsibilities and obligations”, “I often think about the person I am afraid I might become in the future”; “I see myself as someone who is primarily striving to become the self I ‘ought; to be to fulfill my duties, responsibilities, and obligations”; for promotion focus, we included statements such as “I frequently imagine how I will achieve my hopes and aspirations”; “I often think about the person I would ideally like to be in the future”; “I typically focus on the success I hope to achieve in the future”, etc. As part of the survey, participants were also asked to provide demographic information.

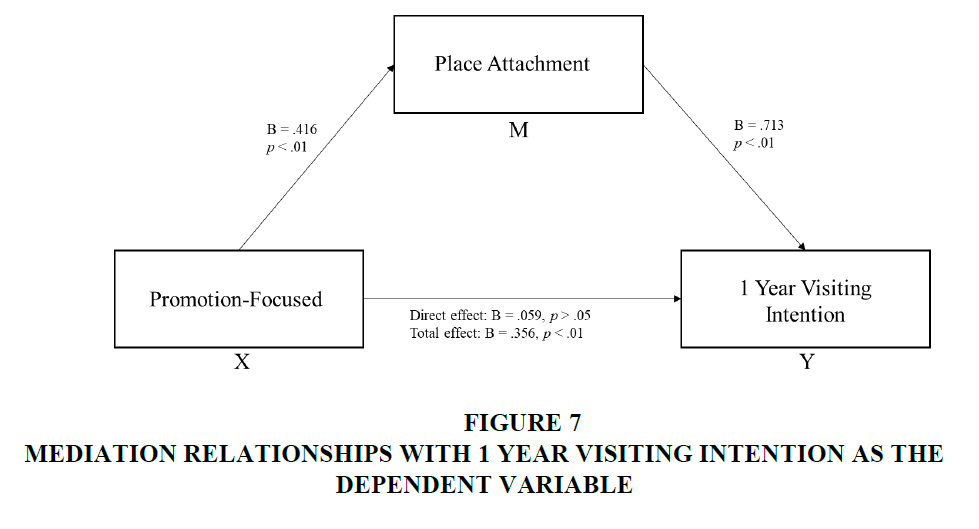

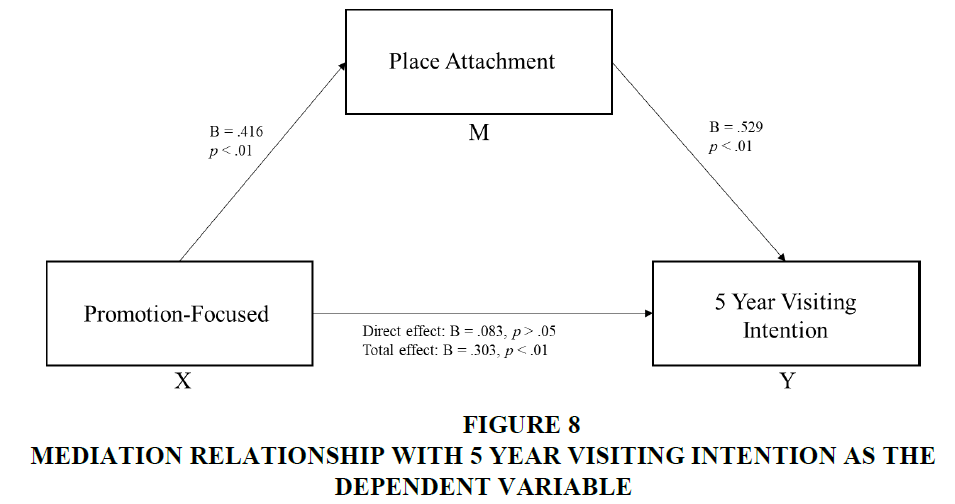

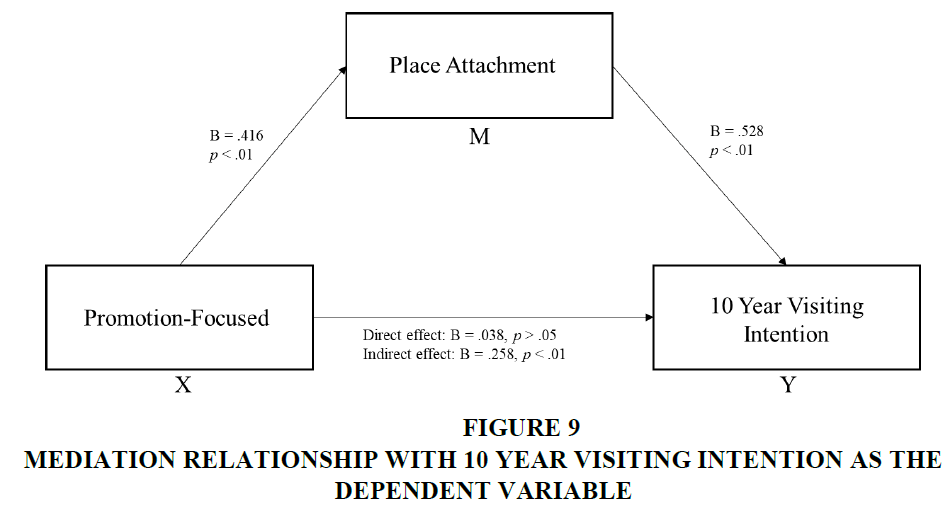

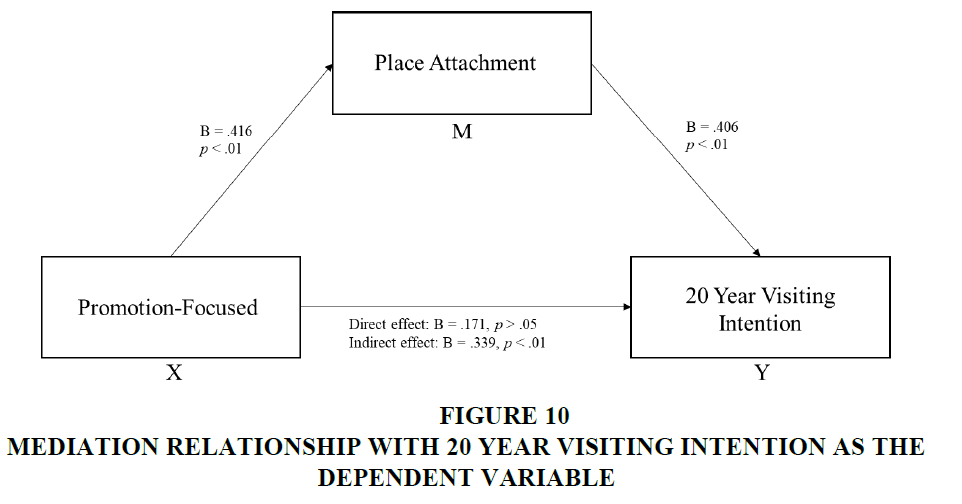

The results showed that place attachment mediates the relationship between promotion focus and 1 year/5 years/10 years/20 years visiting intention for only the participants assigned to the scenario of the place they love. However, a significant relationship does not exist between prevention focus and visiting intention of the place.

For participants that were assigned to report a place they did not at all love, the results showed that there is no significant relationship between place attachment and visiting intention in one year, but a significant relationship for five/ten/twenty/years. Furthermore, a significant relationship exists between promotion focus and intention to visit the place in one year/five years/ten years/twenty years; prevention focus remains significantly associated with visiting intention in one year, however, the relationship is not significant with intention to visit the place in five, ten, or twenty years. The results further support the conclusion that an emotional relationship can only be established if a focus is placed on promoting the prospect of the progress rather than a prevention focus that revolves around preventing the loss. Another finding was also supported by the results: when individuals do not love the place they visit, there is no relationship between the emotional aspect, such as attachment, and the cognitive aspect, such as regulatory focus. As a result, individuals have promotion intentions to develop attachments to direct behavioral intentions based on pure emotions, such as love, and individuals and places are primarily connected by emotion rather than cognitive factors. Additionally, even when individuals do not form an initial emotion, such as love, towards the place, if they still have a regulatory focus, most notably promotion, their intention to visit will still be high, regardless of the emotional aspect, such as attachment to the place. Therefore, the behavioral intention will not be affected by the emotional aspect of the relationship when an individual is promotion oriented rather than prevention oriented. Furthermore, it should be noted that the results of this study are counter intuitive since previous studies have suggested attachment should be formed at the end of a relationship while promotion has already been achieved to a certain extent in relation to the “relationship” goals (e.g., Japutra et al. 2014). Thus, this study suggests that attachment is more natural and spontaneous in nature, regardless of what “efforts” individuals make to achieve the so-called “attachment” goals; it is more of an emotional process.

General Discussion and Managerial Implications

Several aspects of consumption research have shifted from studying the consumption of products to studying the consumption of experiences, since experiential consumption contexts often involve strong emotional attachments as well as cognitive processing. The results of our study indicate that emotional attachment refers to a purely emotional bond between an individual and a place. As noticed in previous studies, place attachment has been associated with feelings of belonging, emotions, and memories (Giuliani 2003), however, this study suggests that place attachment has the potential to contribute to fulfilling consumers’ needs for social insecurity and existential insecurity. Furthermore, place attachment mediates the link between promotion-focused rather than prevention-focused minds and future visits by consumers, particularly when the visitors have emotions such as love toward the place. Promotion focus, however, does not require consumers to form an emotional attachment to a place before forming an intention to visit.

In terms of managerial implications, it has been demonstrated that the experiential component of the tourist experience should be emphasized in a sensory and affective manner and instill an emotional component in order to strengthen the relationship between the individual and the destination. Considering the above, it appears that in order to reduce feelings of insecurity, in particular insecurity about survival and social belonging, tourism spots should be designed to facilitate emotional connections through more interactions and immersive experiences. There is also a need to ensure that the community where the place is located gives the consumer a feeling of belonging so that they can build a connection and attachment to the place. In addition, based on the findings of this study, certain group trips can be organized among family members as a means of establishing a social bond, which in turn relieves the feeling of social insecurity. Additionally, places which emphasize the importance of discovery, personal growth, and well-being may alleviate existential insecurity.

Additionally, from the perspective of experiential consumption, the promotion ad should emphasize how the visit to the place may assist a person in achieving his or her goals. Unique experiences should be highlighted to help enhance not only emotional and cognitive aspects of memorable experiences that individuals may be able to relate to a particular location. As consumers co-create their own experiences when visiting the place, it would be great if these experiences could be customized to enhance the unique goals the tourist wishes to achieve. For example, tourists may wish to explore life by visiting new and unfamiliar locations, or they may wish to gain personal growth by broadening their horizons and perspectives, for creative purposes, lifestyle purposes, or for business opportunities. As part of the tourist experience, tourist destinations should offer visitors the opportunity to incorporate their own aspirations and ambitions and facilitate the pursuit of goals associated with the destination. Promotion focus mindsets are usually continuous and exist regardless of emotional states, so promoting a place to help people achieve goals rather than preventing loss, as in the case of FoMO, may be more effective. Also, putting an emphasis on promotion focus in advertisements will result in a greater number of loyal consumers due to the mediating role that place attachment plays. It is also important that the advertisement frames consumers’ identities as more promotional than preventional in order to create a strong emotional connection and experience. In order to lure new consumers, the advertisements should focus on the way the advertisement helps the new consumer achieve the goals they aspire to achieve. Additionally, the relationship between regulatory focus, particularly promotion focus, and place attachment indicates that through the route of promotion focus, it is easier to build a more positive emotional state, a more positive form of attachment towards the place, which may be utilized to guide future consumption behavior, such as repeating the visits, as consumers develop a strong emotional connection with the place through promotion focus and attachment to the place.

Many aspects of consumption research have shifted from consuming products to consuming experiences as an experiential consumption context often involves strong emotional attachment and cognitive processing. Our results indicate that emotional attachment is a purely emotional construct that refers to an emotional bond between an individual and a place. Though previous studies contend that place attachment is related to sense of belonging, emotions, memories (Giuliani 2003), the findings of this study propose that place attachment can be a great contributor to fulfill consumers’ needs for social insecurity and existential insecurity. Furthermore, place attachment mediates the relationship between promotion focused rather than prevention focused minds and consumers visiting intention in the future especially when consumers have emotions such as love toward the place they visited. However, a promotion focus would not need to go through emotional attachment to form intention to visit if consumers do not have emotions toward the place. The first managerial implication is that the experiential element of the tourist experience should be emphasized in an affective and sensory manner and instill the emotional component to build a stronger relationship between an individual and a place. The above indicate that to relieve the feelings of insecurity, especially the insecurity of surviving and social belongings, tourism spot should be built to encourage the emotional connection by more interactions and immersive experiences when a tourist travels to the place. Additionally, the community that the place is located at should also provide a sense of social belonging to help consumers build a connections and attachment. Also, based on the findings of this study, certain group trips can be defined among family members to create certain social bond which in turn relieves the feeling of social insecurity, while the places that emphasize the value of discovery and personal growth and wellbeing may relieve the feeling of existential insecurity.

Furthermore, from an experiential consumption perspective, to enhance promotion focus which is related to aspirations and goals, the promotion ad about the place should focus on how the visiting place can help an individual achieve his or her life goals. Certain unique experiences should be highlighted to help enhance not only emotional and cognitive aspects of memorable experiences that individuals can relate to the place. Since consumers are usually co creating their own experiences when they visit the place, it would provide a great opportunity if the experiences can be personalized to enhance the unique goals the tourists would like to achieve, in terms of for example, the goal of exploring the life by visiting new and unfamiliar places, the goal of personal growth through widening tourists’ horizons and perspectives, for creativity purposes, lifestyles, for more professional purposes such as attending business opportunities. The places tourist visit should provide an opportunity for tourists to incorporate their own idea of how to achieve aspirations and ambitions and facilitate the pursuit of goals associated with the place visit. Since promotion focus mindsets are typically continuous, and even exist regardless of emotional states, promoting a place to help a person achieve goals rather than preventing the loss, such as an attraction of FoMO, may be more effective. Also, the emphasis of promotion focus will lead to a gain of loyal consumers, through the mediating role of place attachment. Furthermore, consumers’ identities in the advertisement should be framed as more promotion focused rather than prevention focused to build a strong emotional experience and connection with the place. In the advertisement to attract new consumers, the information should be about how ad helps achieve goals. Also, the relationship between regulatory focus, especially promotion focus, with place attachment, indicate that through the route of promotion focus, it is easier to build a more positive emotional state, a more positive form of attachment towards the place, and may guide the future consumption behavior, such as repeating the visiting times of the place, as consumers build a positive emotional relationship with the place through promotion focus and place attachment.

Limitations and Future Studies

It must be noted that some limitations remain in our study. Firstly, our study has only examined place attachment in the context of experiential consumption. In this regard, the construct and scale developed regarding place attachment may be applicable to other contexts in the marketing and tourism industries, such as hospitality, restaurant business, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, augmented reality, etc. Secondly, as a result of the study, we concluded that in order to enhance promotion focus, the promotion ad should describe how the visiting place can assist an individual in accomplishing his or her goals, however we did not validate this conclusion in a subsequent study. Some future studies should be conducted, specifically using experimental design methods, to determine whether promotion-focused advertisements that emphasize individual accomplishment of life goals will result in a stronger sense of place attachment compared to advertisements that do not emphasize individual accomplishments. Moreover, the scale we developed is limited in scope, and if it is used in other contexts besides the experiential consumption context, it must be adapted and revalidated. In future studies, the validity and reliability of the scale should be examined in other marketing contexts to determine whether the scale items still hold up in those contexts when more variables are incorporated into a nomological framework.

References

Asseraf, Y., & Shoham, A. (2017). Destination branding: The role of consumer affinity. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(4), 375-384.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, 74-94.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., Yeager, E. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., & Mimbs, B. P. (2021). Measuring place attachment with the abbreviated place attachment scale (APAS). Journal of environmental psychology, 74, 101577.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The bowlby-ainsworth attachment theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(4), 637-638.

Brown, G., & Raymond, C. (2007). The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Applied geography, 27(2), 89-111.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological methods & research, 21(2), 230-258.

Castañeda García, J. A., Del Valle Galindo, A., & Martínez Suárez, R. (2018). The effect of online and offline experiential marketing on brand equity in the hotel sector. Spanish journal of marketing-ESIC, 22(1), 22-41.

Cutler, S. Q., & Carmichael, B. A. (2010). The dimensions of the tourist experience. The tourism and leisure experience: Consumer and managerial perspectives, 44, 3-26.

Ekinci, Y., Sirakaya-Turk, E., & Preciado, S. (2013). Symbolic consumption of tourism destination brands. Journal of business research, 66(6), 711-718.

Enrique Bigné, J., Mattila, A. S., & Andreu, L. (2008). The impact of experiential consumption cognitions and emotions on behavioral intentions. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(4), 303-315.

Fedorikhin, A., Park, C. W., & Thomson, M. (2008). Beyond fit and attitude: The effect of emotional attachment on consumer responses to brand extensions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18(4), 281-291.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

Giuliani, M. V. (2003). Theory of attachment and place attachment (p. 137). na.

Graziano, T., & Privitera, D. (2020). Cultural heritage, tourist attractiveness and augmented reality: insights from Italy. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(6), 666-679.

Hinde, R. A. (1982). Attachment: Some conceptual and biological issues. The place of attachment in human behavior, 60-76.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of consumer research, 9(2), 132-140.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Hultman, M., Skarmeas, D., Oghazi, P., & Beheshti, H. M. (2015). Achieving tourist loyalty through destination personality, satisfaction, and identification. Journal of Business Research, 68(11), 2227-2231.

Jantzen, C., Fitchett, J., Østergaard, P., & Vetner, M. (2012). Just for fun? The emotional regime of experiential consumption. Marketing Theory, 12(2), 137-154.

Japutra, A., Ekinci, Y., & Simkin, L. (2014). Exploring brand attachment, its determinants and outcomes. Journal of strategic Marketing, 22(7), 616-630.

Jenkins, M., & Griffith, R. (2004). Using personality constructs to predict performance: Narrow or broad bandwidth. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19, 255-269.

Junaid, M., Hou, F., Hussain, K., & Kirmani, A. A. (2019). Brand love: the emotional bridge between experience and engagement, generation-M perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Kemp, E., Jillapalli, R., & Becerra, E. (2014). Healthcare branding: developing emotionally based consumer brand relationships. Journal of Services Marketing.

Kim, J. H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism management, 44, 34-45.

Kuiper, G., & Smit, B. (2014). Imagineering: Innovation in the experience economy. CABI.

Kumar, V., & Kaushik, A. K. (2020). Does experience affect engagement? Role of destination brand engagement in developing brand advocacy and revisit intentions. Journal of travel & tourism marketing, 37(3), 332-346.

Lee, S. H., & Workman, J. E. (2015). Determinants of brand loyalty: self-construal, self-expressive brands, and brand attachment. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 8(1), 12-20.

Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., & Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(4), 854.

Lovoll, H. S., Røysamb, E., & Vittersø, J. (2017). Experiences matter: Positive emotions facilitate intrinsic motivation. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1340083.

Meng, B., & Han, H. (2018). Working-holiday tourism attributes and satisfaction in forming word-of-mouth and revisit intentions: Impact of quantity and quality of intergroup contact. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 347-357.

Peng, J., Strijker, D., & Wu, Q. (2020). Place identity: how far have we come in exploring its meanings?. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 294.

Raymond, C. M., Brown, G., & Weber, D. (2010). The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. Journal of environmental psychology, 30(4), 422-434.

Rindfleisch, A., Burroughs, J. E., & Wong, N. (2009). The safety of objects: Materialism, existential insecurity, and brand connection. Journal of consumer research, 36(1), 1-16.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of psychological research online, 8(2), 23-74.

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of marketing management, 15(1-3), 53-67.

Shahid, S., Paul, J., Gilal, F. G., & Ansari, S. (2022). The role of sensory marketing and brand experience in building emotional attachment and brand loyalty in luxury retail stores. Psychology & Marketing, 39(7), 1398-1412.

Silvia, P. J., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Interesting things and curious people: Exploration and engagement as transient states and enduring strengths. Social and personality psychology compass, 3(5), 785-797.

Swaminathan, V., Stilley, K. M., & Ahluwalia, R. (2009). When brand personality matters: The moderating role of attachment styles. Journal of consumer research, 35(6), 985-1002.

Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Whan Park, C. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of consumer psychology, 15(1), 77-91.

Triantafillidou, A., & Siomkos, G. (2014). Consumption experience outcomes: satisfaction, nostalgia intensity, word-of-mouth communication and behavioural intentions. Journal of Consumer Marketing.

Tsai, C. T. (2016). Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 536-548.

Tsai, S. P. (2020). Augmented reality enhancing place satisfaction for heritage tourism marketing. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(9), 1078-1083.

Wood, E. H., & Masterman, G. (2008, January). Event marketing: Measuring an experience. In 7th International Marketing Trends Congress, Venice (Vol. 35).

Received: 23-Jan-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-14413; Editor assigned: 24-Jan-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-14413(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Jan-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-14413; Revised: 25-Apr-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-14413(R); Published: 16-May-2024