Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Religiosity and Cultural Effect on Digital Entrepreneurs' Empowerment for Business Sustainability

Mahyarni Ilyas Rahim, Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau

Nor Balkish Zakaria, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Astuti Meflinda Agus Salim, Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau

Harkaneri Bakhtiar, Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau

Rahayu Abdul Rahman, Universiti Teknologi MARA Perak

Abstract

Business sustainability has become decisive and spartan complications among small businesses. Entrepreneurs create business opportunities across individual traits, religious and cultural around the globe not to impoverish especially in the modern era of digital. Thus, this research aims to determine the effect of religious and culture on the digital entrepreneurial intention and behavior among the young generation. It also extends the examination to the effect on entrepreneurial behavior. PLS was used to identify the effect between variables on a sample of 180 young people in Riau using the purposive sampling technique with certain criteria. PLS results showed that religion does not affect entrepreneurial intention and behavior. Meanwhile, culture affects the entrepreneurial intention but not behavior, while intention affects behavior. This research specifically used Islamic and Malay culture in Riau Province, Indonesia, as variables. Islam is the dominant religion in Indonesia, while Malay is the culture of the Riau Muslim community.

Keywords

Religion, Culture, Entrepreneur Intention, Entrepreneur Behavior

Introduction

Based on the data from the Central Statistics Agency for 2019, the ratio of entrepreneurs in Indonesia, which was previously 1.67% out of its 225 million population, had increased by 3.10% from previous year. According to the 2018 Global Entrepreneurship Index data, Indonesia is ranked 94th out of 137 countries in terms of entrepreneurship. This position is behind several other Southeast Asian countries, such as Vietnam at 87th, the Philippines at 76th, Thailand at 71st, Malaysia at 58th, Brunei Darussalam at 53rd, and Singapore at 27th. However, the Central Statistics Agency data also stated that unemployment in the country was around 6.88 million in February 2020, marked an increase from 6.82 million, estimated in the same month in 2019.

Meanwhile, the number of workers in February 2020 were 137.91 million, increased by 1.73 million compared to February 2019. This situation has impacted the increasing number of job seekers that cannot be accommodated and remain ultimately unemployed due to the lack of vacancies.

To overcome this unemployment problem, efforts are needed to promote young people to become entrepreneurs. The term 'entrepreneurship' was used and recorded scientifically for the first time by JB Say, followed by Cantillon (Bilgiseven & Kasimo?lu, 2019; Bokhari 2013). Consequently, entrepreneurship is defined as "buying and producing inputs at an unspecified price" (Bilgiseven & Kasimo?lu, 2019; Yüksel, 2015). Cantillon and Say stated that entrepreneurs are risk-takers because they invest their own money (Bilgiseven & Kasimo?lu, 2019). However, the issue of entrepreneurs’ sustainability has become crucial issues as these small businesses can’t coupe in longer term.

Literature Review

According to the most famous economist Joseph Schumpeter, they are innovators who use the process of destroying the status quo of existing products and services to prepare new ones (Ciborowski, 2016; ?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014; Sharma et al., 2013). For instance, the study results by (Mahmood et al., 2019) show that mobile instant messaging is frequently used to advertise and sell products that most needed by young entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship is seen as an alternative to overcoming the problem of unemployment and a way out of poverty (Nakara, Messeghem & Ramaroson, 2019; ?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014; Bogan & Darity, 2008). Based on the narratives above, the important role of entrepreneurs in the economies of developing countries is obvious. Consequently, all involved parties are encouraged to foster entrepreneurial intention and spirit while maintaining local cultural values among the young generation by utilizing IT developments for a better future. Meanwhile, the current COVID-19 pandemic has affected the business sector.

Hence, a major transformation occurring in business design to ensure success in today's economy is the replacement of traditional methods with digital platforms (Rangaswamy et al., 2020; Van Alstyne & Parker, 2017). These platforms have become an attraction for the young generation in developing a business because of the changing behavioral patterns between consumers and producers. Consequently, these patterns occurring during this pandemic make the young generation creative in developing businesses. The above concept corresponds with studies by (Nowi?ski & Haddoud, 2019; Fellnhofer & Puumalainen, 2017), which stated that policymakers tend to agree that entrepreneurship is an instrument to increase economic growth and technological progress.

Generally, the behavior of each individual is shaped by the outside world represented in one's thoughts and preferences (Bilgiseven & Kasimo?lu, 2019; Cacciotti & Hayton, 2017; ?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014; Guerrero, Rialp & Urbano, 2008). Furthermore, behavior is defined as "an organism's response to a particular stimulus." The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen is the most widely used social psychology theory (Neneh, 2019; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Lortie & Castogiovanni, 2015). This theory explains the deep beliefs and global motives under the decisions and actions taken and is the basic model often used in the literature about entrepreneurial intention (Bilgiseven & Kasimo?lu, 2019; Nowi?ski & Haddoud, 2019; ?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014; Schlaegel & Koenig, 2014; Miralles & Riverola, 2012; Fini et al., 2012; Fretschner & Weber, 2013; Do Paço et al., 2011; Kolvereid, 1996; Ajzen, 1991).

The central factor in the theory of planned behavior is the individual's intention to perform certain behaviors. Meanwhile, the intention is assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence behavior and is an indication of how hard people are willing to try and how much effort they plan to perform the behavior. As a general rule, the stronger the intention to engage in a behavior, the greater the possible performance. (Laffranchini, Kim & Posthuma 2018), showed the need to understand the influence culture has on the relationship between entrepreneurial cognition and actual behavior. There is still a significant gap in the research on this cognitive mechanism by which culture influences entrepreneurial behavior (Pathak & Muralidharan, 2018). Most research areas on entrepreneurial cognition are focused on examining the role of state culture (Nowi?ski & Haddoud, 2019; Dheer & Lenartowicz, 2018; Alon et al., 2016; Dheer & Lenartowicz, 2018; Schlaegel, He & Engle, 2013; Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard & Rueda-Cantuche, 2011; Engle et al., 2011; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Bouncken et al., 2009). Many research opportunities in the entrepreneurship field are seen from examining the role of institutions, including culture, on individual entrepreneurial activities at the national level (Terjesen, Couto & Francisco, 2016). Also, (Pathak & Muralidharan, 2018) stated that the role of culture attracts more research, although the mechanisms underlying the formation of entrepreneurial behavior are not yet fully understood. Hence, there is a gap in the role of informal institutions, such as culture, in entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial intention is defined as the process of finding information to achieve the goal of establishing a business (Adhi et al., 2020). According to some experts, there is a strong need to examine the various contextual aspects that affect entrepreneurial intention and behavior (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2016; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Fini et al., 2012; Welter, 2011). Meanwhile, (Zahra & Wright, 2011), stated that the economic development level, financial capital availability, and government regulations are some factors that determine entrepreneurial intention and behavior. Based on the above description, this research considers the entrepreneurial intention using the following indicators; 1) Entrepreneurs are more needed in the future, 2) Having entrepreneurs makes the economy more efficient, 3) Having entrepreneurs helps the government, and 4) Being an entrepreneur is a person's intention from a long time ago.

Meanwhile, entrepreneurial behavior is defined as the level of belief in performing activities (Adhi et al., 2020; Ajzen, 2002; Bock & Kim, 2002). Previous research has shown that the main reason for entering entrepreneurship is the potential economic benefit derived from the business (Guerra & Patuelli, 2016; Holland & Shepherd, 2013). The intangible rewards and psychological factors provided in the activity include the independence, freedom, autonomy, and control obtained by being one's boss (Pardoa & Ruiz-Tagle, 2017; Aspaas, 2004). Conversely, extrinsic rewards refer to success and monetary gain (Khan, Waqas & Muneer, 2017; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). The reasons above are considered in determining the indicators of entrepreneurial behavior, namely increased economic growth and the existence of provisions for entrepreneurship. Other indicators include knowing how, alongside the belief in performing entrepreneurial activities, living with more discipline, and thriftiness.

Islam as an adopted religion has a positive perspective towards entrepreneurs. Prophet Muhammad is known as an entrepreneur who is a role model for Muslims due to his tenacity, professionalism, honesty, trustworthiness, and reliability as a trader. The most basic characteristics of a Muslim are piety and humility towards God and others (Laeheem, 2018; Hesamifar, 2012; Latif, 2008). Meanwhile, Islamic ethics is a system shaped by the Qur'an teachings and explained by Prophet Muhammad through actions and words. Islamic ethics deals with standards that govern what Muslims need to do and addresses the virtues, duties, and attitudes of individuals and society (Laeheem, 2018; Ebrahimi & Yusoff, 2017). Religious factors and principles make individuals behave according to Islamic ethics and recognize right from wrong because they greatly value and develop personality, habits, morality, ethics, and behavior (Laeheem, 2018; Chowdhury, 2016; Laeheem, 2014; Al-Aidaros, Shamsudin & Idris, 2013). Another research states that Muslim entrepreneurs run their business by performing the Prophet Muhammad's sunnah (Adhi et al., 2020; Gursoy et al., 2017; Boshoff, 2009; Bellu & Fiume 2004). Furthermore, religion affects people's behavior in many ways, including the choice to become entrepreneurs and run a business practice (Adhi et al., 2020; Yousef, 2000). Based on the above description, investigating the religious factors affecting individual preferences in entrepreneurial careers is important. In this research, religion is defined as an understanding of the Qur'an and Hadith related to entrepreneurial behavior by measuring the extent to which young people's behaviors are motivated by religious teachings. The indicators are 1) Living life by upholding moral values, 2) a Balance between spiritual and material interests, 3) Blessing, and 4) Faithfulness.

Cultural values are defined as shared and long-term goals of existence (Stephan and Pathak 2016), which develop certain personality traits and motives (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Paul & Shrivatava, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2007; Mueller & Thomas, 2001). Meanwhile, Weber was the first author to query how cultural values influence entrepreneurship, and a century later, this Weberian question is still a matter of debate in entrepreneurship research (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Çelikkol, Kitapçi & Döven, 2019; Paul & Shrivatava, 2016; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Calvelli et al., 2014; Jones, Coviello & Tang, 2011); (Stephan & Uhlaner, 2010). Most of the related research provides evidence of the relationship between entrepreneurship and cultural values, which are specific to each group of people and create personality traits and motives among them (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Liu & Almor, 2016; Paul & Shrivatava, 2016; Chand & Ghorbani, 2011). Other research states that culture plays an important role in individual decision-making (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Paul & Shrivatava, 2016; ?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014; Choi & Geistfeld, 2004). Culture is considered a central factor in determining the independence of a nation. Meanwhile, the Indonesian culture is known to originate from the manners, nature, and personality of each large group of people called society. Consequently, this research emphasizes the Malay culture, which (Tenas, 2015.) defined as a place, community, group, or region in any part of the world that still or has practiced the Malay tradition. The indicators of this practice are 1) humbling themselves, 2) not wanting to be arrogant, 3) not being fierce, 4) gentleness and 5) not lacking simplicity and politeness. The study by (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020), which stated that specific measurements related to the cultural values of certain communities are needed, reinforced the above.

This research has a specific value by including the Islamic religion variable adopted from (Adhi et al., 2020), which examined the important role of religion for individuals in implementing entrepreneurial activities. Meanwhile, the Malay culture variable was adopted from (Pathak & Muralidharan, 2018) regarding the role of culture. It was also taken from (?ahin & Asunakutlu, 2014), which stated that entrepreneurship is seen as an incubator of economic growth, and although entrepreneurial profile may show some similar features around the world, the rest is influenced by culture. According to (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2021; Bosma et al., 2012), non-family role models are considered in developing entrepreneurial intention and behavior. Based on the above description, this research tries to relate the local Malay culture adopted and often used as a national culture in various state events, using specific indicators according to the local community conditions. Islamic teachings are used as a variable that determines entrepreneurial intention and behavior, as this religion has been widely embraced by almost 80% of the Indonesian people. Consequently, this research aims to determine the effect of religious teachings and culture on entrepreneurial intention and behavior, as well as the effect of entrepreneurial intention on the young generation in Riau Province.

Methodology

The population in this research were all young people (n=180) in Riau Province using the purposive sampling technique with the criteria of young people who had a business that had been running for one year and over. This quantitative research examined the relationship between the variables of Islamic religion, culture, entrepreneurial intention, and behavior. The hypothetical narrative is to promote the youth to know, understand, and practice religion strictly, participate in activities to develop their souls, and be trained, according to Islamic principles, so that they behave according to the social norms (Laeheem, 2018; Laeheem, 2014; Laeheem 2013; Chaiprasit & Santidhiraku, 2011; Mahama, 2009). Other research stated that religion affects institutional systems, individuals' decisions to become entrepreneurs, and community behavior in many ways, (Adhi et al., 2020; Van Buren, Syed & Mir, 2020; Yousef, 2000). Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Good religious teachings promote cultural development.

H2: Good religious teachings promote an increased entrepreneurial intention among young people.

H3: Good religious teachings promote an increased entrepreneurial behavior among young people.

Most research proves the relationship between entrepreneurship and cultural values, which are specific to each group of people and create personality traits and motives among communities (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Liu & Almor, 2016; Paul & Shrivatava 2016; Chand & Ghorbani, 2011). Meanwhile, the role of cultural values attached to certain communities, especially the young generation, determines the entrepreneurial intention and behavior with the hypothesis:

H4: A well-understood culture promotes an increased entrepreneurial intention among young people.

H5: A well-understood culture promotes an increased entrepreneurial behavior among young people.

Subsequently, research exploring the relationship between intention and behavior showed a strong correlation between 0.90 and 0.96 (Ajzen, Czasch & Flood, 2009). However, a meta-analysis found that entrepreneurial intention represented 27% of the variance in behavior (Lortie & Castogiovanni, 2015; Guerrero & Urbano, 2012; Armitage & Conner, 2010), examined entrepreneurial behavior as a result of the entrepreneurial intention. Given the strong relationship between intention and behavior to start a business, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H6: The entrepreneurial intention promotes an increased entrepreneurial behavior among young people.

To prove the hypothesis, the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique was used with the research instrument via a 5-point Likert scale. PLS is a powerful analytical method indeterminacy factor, and since it does not assume the data should be with a certain scale measurement or small-scale amount, it is used for theory confirmation, (Hair et al., 2019).

Findings and Discussion

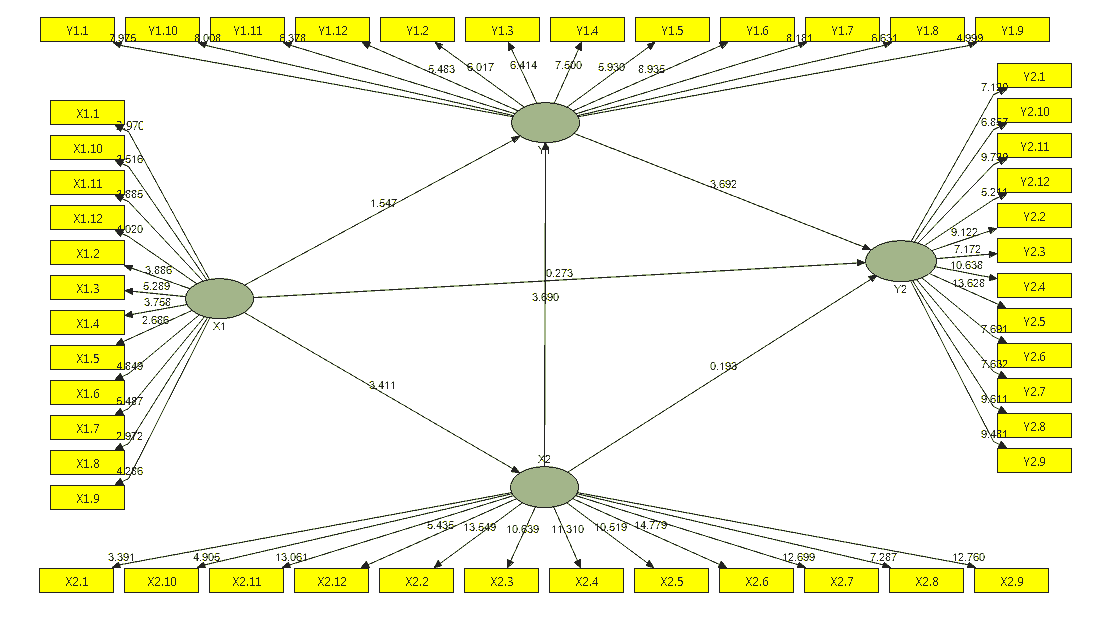

The results of the hypothesis testing using the Structural Model generated in PLS are as follows:

Meanwhile, the data interpretation results from the PLS output are shown in the following table. The t-counts obtained for each variable relationship were compared, and a value greater than the t-table of 1.96 meant the relationship was significant (Table 1).

| Table 1 Path Coefficients Between Research Variables |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| OriginalSample (O) | T Statistics (|O/STERR|) | Interpretation | |

| Religion (X1) -> Culture (X2) | 0.493 | 3.411 | Significant |

| Religion (X1) -> Intention (Y1) | 0.248 | 1.547 | Insignificant |

| Religion (X1) -> Behavior (Y2) | 0.049 | 0.273 | Insignificant |

| Culture (X2) -> Intention (Y1) | 0.51 | 3.69 | Significant |

| Culture (X2) -> Behavior (Y2) | 0.035 | 0.193 | Insignificant |

| intention (Y1) -> Behavior (Y2) | 0.728 | 3.692 | Significant |

Interpretation of structural model test results for the effect between the following variables:

The Effect of Religion on Culture

The religion variable had a positive effect on culture, at a path coefficient value of 0.493, showing that a good understanding of religious teachings promotes an increased understanding of culture. Meanwhile, the t-count of the religion variable was 3.411, which is greater than the 1.96 t-table value, showing that religion has a significant effect on culture. Hence, good religious teachings promote increased cultural understanding among the young people in Riau.

Islam is currently the second-largest religion in the world after Christianity (Jamaludin et al., 2018). According to (Desilver & Masci, 2017), this number continues to grow, hence, Islam is believed to be the fastest-growing religious group and is expected to surpass Christianity in the next two decades (Jamaludin et al., 2018; Lipka & Hackett, 2017). Islam is not just a belief but a way of life, and Muslims practice this religion as an act of worshiping God through the obligatory prayers, alongside in all aspects of life, such as business, trade, and others. A good understanding of Islamic teachings has colored the interpretation of the Malay culture in the everyday life of the Riau people, who are used to and bound by these teachings and values.

The Effect of Religion on Entrepreneurial Intention

The religion variable had no effect on the entrepreneurial intention, as observed by a path coefficient of 0.248. This shows that the intention decreases as the understanding of religion increases. Meanwhile, the t-count of the religion variable was 1.547, which is smaller than the 1.96 t-table value, showing that religion has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial intention. Hence, a good understanding of religious teachings has not promoted the entrepreneurial intention among young people in Riau. This finding does not correspond with the studies by (Laeheem, 2018; Laeheem, 2014; Mahama, 2009). According to them, individuals behave according to Islamic ethics because of religion and recognize right from wrong due to their high values, developed personalities, habits, morality, ethics, and behavior. Currently, understanding the meaning of Islamic teachings properly has not changed the entrepreneurial intention of young people, and a continuous process is to relate it to independence in life.

The Effect of Religion on Entrepreneurial Behavior

The religion variable had no effect on entrepreneurial behavior, according to the path coefficient of 0.049, showing that entrepreneurial behavior decreases with an increase in the understanding of religion. Meanwhile, the t-count of religion was 0.273, which is smaller than the t-table value of 1.96. This shows that religion has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial behavior, and good religious teachings do not promote an increased entrepreneurial behavior among the young people in Riau. This result is not in line with the studies by (Adhi et al., 2020; Yousef, 2000), which stated that religion affects people's behavior in many ways, including the choice to become entrepreneurs and run a business practice. Consequently, this research states that Islamic teachings are not a driving force for young people to become entrepreneurs. Therefore, efforts are needed to set a good example in developing businesses from parents and families that have made entrepreneurship their main profession. Furthermore, support from external parties, such as the government, is also needed to provide facilities, including capital loans, training, promotions, and easy access to IT.

The Effect of Culture on the Entrepreneurial Intention

The culture variable had a positive effect on the entrepreneurial intention, at a path coefficient of 0.510, showing that entrepreneurial intention increases with a good understanding of culture. Meanwhile, the t-count of this variable was 3.690, which is greater than the t-table value of 1.96, showing that culture has a significant effect on entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, a well-understood culture promotes an increased entrepreneurial intention among young people in Riau. This result supports research, which proves that the relationship between entrepreneurship and cultural values are specific to each group of people and create personality traits and motives among communities (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Liu & Almor, 2016; Paul & Shrivatava, 2016; Chand & Ghorbani, 2011). The role of cultural values attached to certain communities, especially the young generation, determines entrepreneurial intention and behavior. So far, the Malay culture is well understood by young people, promoting them to become entrepreneurs. The values in the culture contain advice and teach individuals to be independent in everyday life, with the expression Adat bersendi syarak, syarak bersendi Kitabullah, and meaning 'customary and religious rules should be remembered during all work.'

The Effect of Culture on Entrepreneurial Behavior

The culture variable did not affect the entrepreneurial behavior, as shown by the path coefficient of 0.035, showing that it increases when culture is well understood. Meanwhile, the culture t-count score was 0.193, which is smaller than the t-table value of 1.96, showing that the culture variable has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial behavior. Hence, a well-understood culture does not promote an increased entrepreneurial behavior among young people in Riau. This result corresponds with research, which stated that there is a gap regarding the effect of culture on entrepreneurial behavior, and more comprehensive studies are needed (Pathak & Muralidharan, 2018). Meanwhile, some experts referred to the various existing knowledge gaps in understanding the effect of culture on entrepreneurship (Liu & Almor, 2016; Chand & Ghorbani, 2011). However, based on interviews, experts expressed hope that Malay culture in the future should be the driving force for developing entrepreneurial behavior. Therefore, efforts are needed to develop the cultural values that teach hard work and independence.

The Effect of Intention on Entrepreneurial Behavior

The intention variable had a positive effect on the entrepreneurial behavior, according to the path coefficient value of 0.728, showing that entrepreneurial behavior increases along with the intention. Meanwhile, the intention variable had a t-count of 3.692, which is greater than the t-table of 1.96. This shows that intention has a significant effect and promotes entrepreneurial behavior among young people in Riau. Consequently, this result corresponds with (Calza, Cannavale & Zohoorian, 2020; Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2016; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Fini et al., 2012; Welter, 2011; Zahra & Wright, 2011). These studies stated that intention affects one's entrepreneurial behavior because it determines economic development, financial capital availability, and government regulations. Furthermore, it is also in line with (Lortie & Castogiovanni, 2015; Guerrero & Urbano, 2012), which examined this hypothesis. The above findings are also consistent with this research, which states that intention has a relationship with entrepreneurial behavior. Based on interview results, several young people stated that entrepreneurial intention promotes behavior by following and updating their knowledge through seminars and training related to entrepreneurial problems and IT development with certain communities.

Conclusion

Based on hypothesis testing, the following conclusions were made. Religion has a significant effect on culture. Hence, good religious teachings promote increased understanding of culture among young people in Riau. Religion has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, good teachings do not promote this intention among young people in Riau. Religion has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial behavior. Hence, good religious teachings do not promote this behavior among young people in Riau. Culture has a significant effect on entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, an increased understanding enhances this intention among young people in Riau. Culture has an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial behavior. Therefore, an increased understanding does not enhance entrepreneurial behavior among young people in Riau. Intention has a significant effect on entrepreneurial behavior. Hence, an increased intention promotes entrepreneurial behavior among young people in Riau.

Acknowledgement

This study acknowledges the helps of Accounting Research Institute of Universiti Teknologi MARA along the research processes.

References

- Abbasianchavari, A., & Alexandra, M. (2021). The impact of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: A review of the literature. Management Review Quarterly, 71. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00179-0.

- Adhi, L.K.S., Niken, I.S.P., & Muhammad, M.R. (2020). “Religion, attitude, and entrepreneurial intention in Indonesia” 14(1),44–62.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). “The theory of planned behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Ajzen, I. (2002). “Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x.

- Ajzen, I., Cornelia, C., & Michael, G.F. (2009). “From intentions to behavior: Implementation intention, commitment, and conscientiousness.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 1356–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00485.x.

- Al-Aidaros, A.-H., Faridahwati, M.S., & Kamil, M.I. (2013). “Ethics and ethical theories from an islamic perspective.” International Journal of Islamic Thought, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.24035/ijit.04.2013.001.

- Alon, I., Michele, B., Judith, M., & Vasyl, T. (2016). “The development and validation of the business cultural intelligence quotient.” Cross Cultural and Strategic Management, 23(1), 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-10-2015-0138.

- Alstyne, M.V., & Geoffrey, P. (2017). “Platform business: From resources to relationships.” NIM Marketing Intelligence Review, 9(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/gfkmir-2017-0004.

- Armitage, C.J., & Mark, C. (2010). “Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour?: A meta-analytic review E Y Cacy of the theory of planned behaviour.” A Meta-Analytic Review, 471–99.

- Aspaas, H.R. (2004). “Minority women’s microenterprises in rural areas of the united states of America: African American, Hispanic American and Native American Case Studies.” GeoJournal, 61(3), 281–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-004-3689-0.

- Bellu, R.R., & Peter, F. (2004). “Religiosity and entrepreneurial behaviour.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 5(3), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.5367/0000000041513411.

- Bilgiseven, E.B., & Murat, K. (2019). “Analysis of factors leading to entrepreneurial intention.” Procedia Computer Science, 158, 885–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.127.

- Bock, G.W., & Young, G.K. (2002). “Breaking the myths of rewards: An exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing.” Information Resources Management Journal (IRMJ), 15(2), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.4018/irmj.2002040102.

- Bogan, V., & William, D. (2008). “Culture and entrepreneurship? African American and immigrant self-employment in the United States.” Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(5), 1999–2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2007.10.010.

- Bokhari, A. (2013). “Entrepreneurship as a solution to youth unemployment in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.” American Journal of Sciencific Research, February: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4585-97-2_19-1.

- Boshoff, N. (2009). “Neo-colonialism and research collaboration in Central Africa.” Scientometrics, 81(2), 413–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-2211-8.

- Bosma, N., Jolanda, H., Veronique, S., Mirjam, V.P., & Ingrid, V. (2012). “Entrepreneurship and role models.” Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004.

- Bouncken, R.B., Jevgenija, Z., Andreas, G., & Anna M. (2009). “a comparative study of cultural influences on intentions to found a new venture in Germany and Poland.” International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 3(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2009.021631.

- Buren, H.J.V., Jawad, S., & Raza, M. (2020). “Religion as a macro social force affecting business: Concepts, questions, and future research.” Business and Society, 59(5), 799–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319845097.

- Cacciotti, G., & James, C.H. (2017). “National culture and entrepreneurship.” The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship, no. January 2011, 401–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970812.ch18.

- Calvelli, A., Chiara, C., Adele, P., & Ilaria, T. (2014). “Do ‘cultural gaps’ affect entrepreneurial activities? An analysis based on globe’s dimensions.” European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management, 3 (3/4), 279. https://doi.org/10.1504/ejccm.2014.071969.

- Calza, F., Chiara, C., & Iman, Z.N. (2020). “How do cultural values influence entrepreneurial behavior of nations? A behavioral reasoning approach.” International Business Review, 29(5), 101725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101725.

- Çelikkol, M., Hakan, K., & Gözde, D. (2019). “Culture’s impact on entrepreneurship & interaction effect of economic development level: An 81 country study.” Journal of Business Economics and Management, 20(4), 777–97. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2019.10180.

- Chaiprasit, K., & Orapin, S. (2011). “Happiness at work of employees in small and medium-sized enterprises, Thailand.” Procedia - Social Nand Behavioral Sciences, 25, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.540.

- Chand, M., & Majid, G. (2011). “National culture, networks and ethnic entrepreneurship: A comparison of the Indian and Chinese immigrants in the US.” International Business Review, 20(6), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.02.009.

- Choi, J., & Loren, V.G. (2004). “A cross-cultural investigation of consumer e-shopping adoption.” Journal of Economic Psychology, 25(6), 821–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2003.08.006.

- Chowdhury, M. (2016). “Emphasizing morals, values, ethics, and character education in science education and science teaching.” The Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences (MOJES), 4(2), 1–16.

- Ciborowski, R. (2016). “Innovation systems in the terms of schumpeterian crea-tive destruction.” EUREKA: Social and Humanities, 4(4), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.21303/2504-5571.2016.00114.

- Desilver & Masci. (n.d). “Home research topics religion religions islam muslims around the world.”

- Dheer, Ratan, J.S., & Tomasz, L. (2018). “Multiculturalism and entrepreneurial intentions: Understanding the mediating role of cognitions.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 42(3), 426–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12260.

- Ebrahimi, M., & Kamaruzaman, Y. (2017). “Islamic identity, ethical principles and human values.” European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 6(1), 325. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejms.v6i1.p325-336.

- Engle, P.L., Lia, C.H.F., Harold, A., Jere, B., Chloe, O’G., Aisha, Y., … & Selim, I. (2011). “Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries.” The Lancet, 378(9799), 1339–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60889-1.

- Fellnhofer, K., & Kaisu, P. (2017). “Can role models boost entrepreneurial attitudes?” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 21(3), 274–90. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2017.083476.

- Fini, R., Rosa, G., Gian, L.M., & Maurizio, S. (2012). “The determinants of corporate entrepreneurial intention within small and newly established firms.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 36(2), 387–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00411.x.

- Fretschner, M., & Susanne, W. (2013). “Measuring and understanding the effects of entrepreneurial awareness education.” Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 410–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12019.

- Guerra, G., & Roberto, P. (2016). “The role of job satisfaction in transitions into self-employment.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 40(3), 543–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12133.

- Guerrero, M., Josep, R., & David, U. (2008). “The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: a structural equation model.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0032-x.

- Guerrero, M., & David, U. (2012). “The development of an entrepreneurial university.” Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9171-x.

- Gursoy, D., Medet, Y., Manuel, A.R., & Alexandre, P.N. (2017). “Impact of trust on local residents’ mega-event perceptions and their support.” Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516643415.

- Hair, J.F., Barry, J.B., Rolph, E.A., & William, C.B. (2019). Multivariate data analysis,(Eighth Edition). Annabel Ainscow.

- Hesamifar, A. (2012). “islamic ethics and intrinsic value of human being.” Journal of Philosophical Investigations, 6(11), 109–19.

- Holland, D.V., & Dean, A.S. (2013). “Deciding to persist: Adversity, values, and entrepreneurs’ decision policies.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 37(2), 331–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00468.x.

- Jamaludin, M.A., Nur, D.A.R., Nurrulhidayah, A.F., & Anuar, M.R. (2018). “Religious and cultural influences on the selection of menu.” Preparation and Processing of Religious and Cultural Foods. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-101892-7.00002-X.

- Jones, M.V., Nicole, C., & Yee, K.T. (2011). “International entrepreneurship research (1989-2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis.” Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 632–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.001.

- Katumi, M. (2009). University of Birmingham, and This, 2009. “The Educational Needs Of Muslim Women in Ghana,” 12–42.

- Khan, N., Hafiz, W., & Rizwan, M. (2017). “Impact of rewards (intrinsic and extrinsic) on employee performance with special reference to courier companies of city Faisalabad, Pakistan.” International Journal of Management Excellence, 8(2), 937–45. https://doi.org/10.17722/ijme.v8i2.894.

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). “Prediction of employment status choice intentions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602100104.

- Laeheem, K. (2013). “Factors Associated with Bullying Behavior in Islamic Private Schools, Pattani Province, Southern Thailand.” Asian Social Science, 9(3), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n3p55.

- Kasetchai, L. (2014). “Factors associated with islamic behavior among Thai Muslim youth in the three southern border provinces, Thailand.” Kasetsart Journal - Social Sciences, 35(2), 356–67.

- Kasetchai, L. (2018). “Relationships between islamic ethical behavior and islamic factors among muslim youths in the three southern border provinces of Thailand.” Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(2), 305–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.03.005.

- Laffranchini, G., Si, H.K., & Richard, A.P. (2018). “A metacultural approach to predicting self-employment across the globe.” International Business Review, 27(2), 481–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.10.001.

- Latif, K. (2008). “Morality and ethics in Islam.” Islamic Morals and Practices, 1–3. http://www.islamreligion.com/articles/1943/.

- Liñán, F., & Alain, F. (2015). “A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 11 (4): 907–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0356-5.

- Liñán, F., Juan, C.R.-C., & José, M.R.-C. (2011). “Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0154-z.

- Liñán, F., & Yi-wen, C. (2009). “Max ( e T , e T ),” no. 979: 1000. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Liñán+%26+Chen%2C+2009%3B.

- Lipka & Hackett (2017). “Religions islam muslims around the world.”

- Liu, Y., & Tamar, A. (2016). “How culture influences the way entrepreneurs deal with uncertainty in inter-organizational relationships: The case of returnee versus local entrepreneurs in China.” International Business Review, 25(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.11.002.

- Lortie, J., & Gary, C. (2015). “The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 935–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0358-3.

- Mahmood, C.F.C., Nazihah, O., Norshaieda, A.A., & Nor, B.Z. (2019). “Capitalising on mobile instant messaging for undergraduates business empowerment.” Asia-Pacific Management Accounting Journal, 14(3), 1–18.

- Mitchell, R.K., Lowell, W.B., Barbara, B., Connie, M.G., Jeffery, S.M.M., Eric, A.M., & Brock, S.J. (2007). “The central question in entrepreneurial cognition research.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 31(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00161.x.

- Mueller, S.L., & Anisya, S.T. (2001). “Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness.” Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00039-7.

- Nakara, W.A., Karim, M., & Andry, R. (2019). “Innovation and entrepreneurship in a context of poverty: A multilevel approach.” Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00281-3.

- Neneh, B.N. (2019). “From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112(April), 311–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.04.005.

- Nowi?ski, W., & Mohamed, Y.H. (2019). “The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention.” Journal of Business Research, 96(June 2018), 183–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.005.

- Paço, A.D., João, F., Mário, R., Ricardo, G.R., & Anabela, D. (2011). “Entrepreneurial intention among secondary students: Findings from Portugal.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2011.040418.

- Pardoa, B.C., & Jaime, R.-T. (2017). “The dynamic role of specific experience in the selection of self-employment versus wage-employment.” Oxford Economic Papers, 69(1), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpw047.

- Pathak, S., & Etayankara, M. (2018). “Economic inequality and social entrepreneurship.” Business and Society, 57(6), 1150–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650317696069.

- Paul, J., & Archana, S. (2016). “Do young managers in a developing country have stronger entrepreneurial intentions? Theory and Debate.” International Business Review, 25(6), 1197–1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.03.003.

- Rangaswamy, A., Nicole, M., Claudio, F., Gerrit, V.B., Jaap, E.W., & Jochen, W. (2020). “The role of marketing in digital business platforms.” Journal of Interactive Marketing, 51, 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.04.006.

- ?ahin, T.K., & Tuncer, A. (2014). “Entrepreneurship in a cultural context: A research on turks in Bulgaria.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 851–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.094.

- Salle, L., & Ramon, L. (2012). “Entrepreneurial intention?: An empirical insight to nascent entrepreneurs francesc miralles * Carla Riverola.” The XXIII ISPIM Conference – Action for Innovation: Innovating from Experience – in Barcelona, June.

- Schlaegel, C., Xiaohong, H., & Robert, E. (2013). “The direct and indirect influences of national culture on entrepreneurial intentions: A fourteen nation study.” International Journal of Management, 30(2), 597.

- Schlaegel, C., & Michael, K. (2014). “Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12087.

- Sharma, M., Vandana, C., Rajni, B., & Ranchan, C. (2013). “Rural entrepreneurship in developing countries: Challenges, problems and performance appraisal.” Global Journal of Management and Business Studies, 3(9), 1035–40. http://www.ripublication.com/gjmbs.htm.

- Shirokova, G., Oleksiy, O., & Karina, B. (2016). “Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics.” European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.007.

- Stephan, U., & Saurav, P. (2016). “Beyond cultural values? Cultural leadership ideals and entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing, 31(5), 505–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.07.003.

- Stephan, U., & Lorraine, M.U. (2010). “Performance-based vs socially supportive culture: A cross-national study of descriptive norms and entrepreneurship.” Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1347–64. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.14.

- Tenas, E. ( n.d). Tenas Effendi 2015.Pdf.

- Terjesen, S., Eduardo, B.C., & Paulo, M.F. (2016). “Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity.” Journal of Management and Governance, 20(3), 447–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-014-9307-8.

- Welter, F. (2011). “Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x.

- Wiklund, J., & Dean, S. (2003). “Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses.” Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.360.

- Yousef, D.A. (2000). “Organizational commitment: A mediator of the relationships of leadership behavior with job satisfaction and performance in a non-western country.” Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940010305270