Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 1S

Quiet Quitting by E-Commerce Delivery Workers Moderated by Job Resources and Employee Grit: A Symbolic Interaction Approach

Paramjit Singh Lamba, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Anil Anand Pathak, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Neera Jain, Management Development Institute, Gurgaon

Citation Information: Lamba, P.S., Pathak, A.A., & Jain, N. (2025). Quiet quitting by e-commerce delivery workers moderated by job resources and employee grit: A symbolic interaction approach. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S1), 1-20.

Abstract

Literature suggests that employees not working full time in office often experience a disengagement from their workplace, which leads to alienation, burnout and eventual quiet quitting. This study examines the moderating influence of job resources and grit on the relationship between job demands-burnout and burnout-quiet quitting. Since communication between the supervisor and the employee plays a key role in job resources and developing passion in employees towards their jobs, this study uses the symbolic interaction theory as a lens to study the moderating effect. Data collected from 419 e-commerce delivery workers is analysed using SmartPLS 4. This study, probably among the first of its kind in e-commerce delivery worker context, reveals that job resources have a moderate influence on the job demands-burnout and burnout-quiet quitting relationship, whereas employee grit has a significant effect on the same relationships. Organizations can reduce employee burnout and quiet quitting by developing employee’s passion towards the workplace, thereby avoiding loss of productivity.

Keywords

Quiet Quitting, Remote Workers, Burnout, Passion, Grit, Supervisor Communication, Job Demands, Digital Business.

Introduction

With the growth in home deliveries, research on these delivery workers has become a focus area (Serenko, 2024). Since this area gained traction worldwide only during the pandemic, literature on this theme is limited. With a substantial growth in this industry, this subject matter has a lot of importance from the perspective of service management, consumer behaviour, work environment of the e-commerce delivery workers and the job stress therein. Such work falls under the service domain, which is mostly processed by humans (Wu and Wei, 2024). Since humans are complex beings with emotions, their engagement and disengagement has multifarious implications on their performance which in turn determines the organization’s success or failure.

Companies that provide the last mile delivery solutions for e-commerce platforms viz. Amazon, Flipkart, Myntra, or TataCliq represent a new category of organizations that have the potential to leverage their resources for multiple other organizations simultaneously. Technology has changed the way provision stores deliver to customers. Consumption patterns of customers has also metamorphosed over the years. Now, most working professionals live away from their families and the daily hectic work schedule does not leave the working professionals with much time to go offline shopping. Hence, they find it convenient to have most products delivered to their door steps online. Multiple factors affect the increase in online delivery of groceries, apparel and other products and among the key factors is the increasing spread of smartphone applications (Chai and Yat, 2019). With an increase in online deliveries in e-commerce, many ventures started and grew in this space and employment opportunities surged. Since delivery work requires driving as a main skill with low levels of other skills, a large segment of population in the urban and the semi-urban areas has got jobs in this sector. As most of these workers have very basic qualifications and little or no prior workplace related training, especially customer interfacing skills, the organizations have encountered work related problems like disengagement, employee burnout (EBO) and quiet quitting (QQ).

QQ is displayed by employees who do the bare minimum work required to stay employed in that organization (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006). They do not make any extra efforts, or take on additional duties, or participate in any extra-curricular activity at the workplace. The term ‘quiet quitting’ gained prominence when Zaid Khan, a 24-year-old New Yorker, posted a video on TikTok giving the definition of QQ as “You’re not outright quitting your job, but you’re quitting the idea of going above and beyond”. QQ is the act of reducing the level of input and productivity at the workplace by the employee in a conscious manner (Hamouche et al., 2023). This includes a change in attitude towards work, decreased engagement with one’s work and workplace, and a negligible motivation to work (Zenger and Folkman, 2022). The employees in this mode invest their bare minimum effort and meet just the bare requirements at work (Carmichael, 2022; Wade, 2022).

At work, employees demonstrate QQ in various ways. Some of the ways are to not wait and finish a task on the same day even if it takes a few minutes more such as deferring to fulfil a request to the next day, just because the work timings are over; not responding to an important email which is received after an hour after work hours; not feeling guilty about taking a casual day off despite urgency at work, and other such situations; not volunteering to help in a critical customer situation if it means staying back for an hour or two after work. This attitude of doing only what is necessary can often put the organization at a disadvantage against its competition that may have employees who are willing to go above and beyond their core duties. The approach of stretching beyond a given job description is important since most roles cannot be encapsulated in a short job description, and employees need to adapt and evolve as the organization grows and faces new challenges frequently. Many leaders feel that disengaged employees continuing to work with the company is a worse situation compared to their exit, since the colleagues of the quiet quitters have to bear the burden of extra work. This may impact the culture of the organization, performance management and manpower costs negatively.

Gallup (2022) a global workforce report, states that a minimum of 50% of the U.S. workforce is quiet quitting. Only 32% of the workers are engaged with their workplace and 60% of the employees are emotionally detached at work. The report states that 70% of team engagement depends on the supervisor.

QQ is often viewed as a way to cope with EBO and overwork (Lord, 2022). The disengagement of the delivery employees causes negative impact on customer satisfaction, delayed deliveries, and damage to the brand’s loyalty (Lai et al., 2022). Hamouche et al. (2023) posit that QQ is likely to become more prevalent in future.

To avoid QQ, Wilkinson (2022) recommends workforce engagement using a human-centred approach, while Cieniewicz (2023) suggests team management training for supervisors. Ratnatunga (2022) posits that workplaces need to be supportive and inspire people, while Formica and Sfodera (2022) emphasize that employees need to be provided meaning and purpose at work. Serenko (2023) states that motivation can help avoid EBO and QQ. Therefore, it is important that supervisors communicate proactively with their team members to create a positive and engaging environment at the workplace and discover developmental opportunities for the employees.

Previous studies have explored the concept of QQ in healthcare (Rossi et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2023), tourism and hospitality (Rocha et al, 2024, Hamouche et al., 2023), and social work (Lai et al., 2023) sectors. This study examines QQ in the context of e-commerce delivery workers.

This research answers the call of the Pevec (2023) and Kang et al (2023), and provides further insights of how organizations may prevent QQ, by analysing the moderating impact of job resources (JR) and employee grit on the relationship between job demands (JD) and EBO as well as the relationship between EBO and QQ.

The analysis is based on related literature and a survey conducted across 419 delivery workers. Using the symbolic interaction theory as a lens, this study provides theoretical and practical insights to the antecedents of QQ and explores how JR and employee grit influence the decision of the employee to go into QQ mode. Additionally, this study expects further scholarly effort to delve into various factors which may moderate the phenomenon of QQ.

The introduction of this study is followed by a review of literature on the various constructs examined. This is followed by a theoretical background, conceptual framework and hypotheses. Thereafter the methodology, data analysis and results are explained. Towards the end, discussions, conclusions and implications are presented. The study ends with its limitations and recommendations for future research.

Literature Review

Job Demands

Job demands imply the physical, mental, social, or organizational aspects of a job that demand sustained effort or skills, leading to certain physical or mental costs (Bakker et al., 2004). The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model suggests that jobs entail both stress-inducing factors (demands) and supportive factors (resources), which impact employees’ well-being, actions, and productivity (Demerouti et al., 2001). Understanding the Job-Demands (JD) can assist researchers in pinpointing the specific stressors that contribute to psychological detachment seen in QQ. This includes constructs related to physical and emotional job demands. The moderating effect of constructs such as JR, which include supervisory communication and support as well as connectedness with colleagues, and grit, which includes passion and perseverance can also be examined. The influence of these moderators is viewed from the lens of Symbolic Interaction theory.

Symbolic interaction involves the interpretation of actions because symbolic meanings can vary among individuals. The key prerequisite for the formation of meaning is the occurrence of an event. As emphasized by Blumer (1969), "the meaning of things guides action". Symbolic interaction studies the meanings which emerge from individuals interacting in a social environment (Aksan et al., 2009). To comprehend human behaviours, it's imperative to grasp the definitions, meanings, and processes constructed by humans. Elements such as social roles, rules, and structures offer the necessary material for individuals to formulate definitions. In this context, symbolic interaction underscores the importance of social interaction, and the assumption of empathetic roles among people. Symbolic interaction thus forms the backdrop of motivating as well as demotivating interactions between the employee and their supervisor.

Within the workplace, employees encounter diverse job demands, including exposure to hazards and tasks that require significant cognitive and physical effort. The JD-R model, presented by Demerouti et al. (2001), posits that the working environment's conditions, perceived as job demands (JD), can lead to EBO and various health concerns. EBO is often seen as a response to the intense emotional pressures individuals face on the jobs that involve serving others (Maslach, 1978). It is described as a condition marked by feeling emotionally drained, disconnected, and cynical towards both the people they serve and their colleagues, alongside a diminished sense of achievement (Maslach, 1978). EBO comprises of two components viz. emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Demerouti et al., 1991). The present study includes these two components to explore the moderation of the relationship between JR and EBO.

Burnout

Burnout affects a significant population of employees (Fisher et al., 2023). Most of the research on EBO has focused on mental health (Gribben and Semple, 2021). Comparatively, less focus has been on how employees cope with EBO. In recent years, changes in the work-place landscape, such as work from home, remote jobs, and hybrid roles offer employees a better perceived work-life balance. However, the blurring between work and non-work demands have made the employees feel that they need to be available for work all the time (Holden et al., 2018). Literature shows that EBO is associated with lower satisfaction with work-life balance (Boamah et al., 2022).

Employees in e-commerce experiencing high workload seek ways to reduce their JD (Formida and Sfodera, 2022). EBO, is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy (Maslach, 2011). Emotional exhaustion, a primary dimension of EBO, describes the feeling of being overwhelmed at work (Halbesleben and Bowler, 2007; Maslach and Leiter, 2017). Cynicism reflects indifference towards work, while low professional efficacy indicates a decline in work quality. For professional drivers, particularly bus drivers, EBO is strongly associated with health issues and risky driving behaviours (Chen and Kao, 2013). Research, including a study on Taiwanese transport drivers, highlights a direct link between EBO and crash occurrences (Chung and Wu, 2013). In addition, EBO is connected to a rise in occupational incidents among professional drivers (Useche et al., 2018).

EBO transforms well performing employees into ineffective, indifferent and frequently absent employees, leading to lowered efficacy levels. A burnt out employee has negative effects on other workers. EBO leads to stress, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, vulnerability to illness, and can spill over to personal relationships.

Customer service roles, due to their demanding nature and frequent interpersonal interactions, are considered particularly susceptible to employee burnout (Singh, 2000). However, research exploring the causes and effects of EBO within service contexts, especially delivery workers, remains limited, even though EBO has been studied in the context of nursing, teaching, and social work, predominantly in Western cultural contexts (Tang, 1998).

When e-commerce delivery workers are either unwilling or incapable of providing service at the required standard, it adversely affects service quality (Zeithaml et al., 1990). Consequently, the inclination of service employees to deliver high-quality service significantly impacts an organization's efforts to meet customer expectations (Zeithaml et al., 1990). Establishing these expectations, set by both customers and management, is challenging. This challenge stems from the unique characteristics of services, including intangibility, simultaneous production and consumption, perishability, and the high degree of human interaction involved in service delivery (Kandampully, 2006). Service delivery hinges on human interaction, necessitating service employees to demonstrate high levels of empathy and emotional involvement. These distinctive job characteristics can be intricate and demanding (Dormann and Zapf, 2004).

If delivery employees undergo EBO due to a depletion of resources, they may adjust their work attitudes in various ways. This adjustment could involve reducing work objectives, taking less personal responsibility for outcomes, distancing themselves emotionally from their work, and exhibiting more self-centred behaviours (Cherniss, 1980). These efforts often lead to wider service gaps and worsen existing issues. As ongoing resource losses persist, emotional distress tends to escalate, accompanied by a decline in feelings of competence and accomplishment at work, which in turn drives the employee towards QQ (Formica and Sfodera, 2022; Yildiz, 2023).

Quiet Quitting

Quiet quitting has been defined as “employee’s withdrawal” due to the continual hustle at work. In this mode, the employee “exhibits low work engagement and dissatisfaction” and may experience stress, anxiety or anger against the workplace that “reduces well-being and causes work-family conflict as well as other psychological issues” (Yikilmaz, 2022).

QQ is seen to be more widespread among the younger generation, as their experience of the pandemic was mostly negative while they were transitioning into adulthood in personal as well as professional terms (Goh and Baum, 2021). This disrupted transition affected their mental health. The layoffs across the world gave them a career shock. For many, the entry into the job market was delayed, which affected their relationships, health and family. These events drove them to seek a more balanced work-life future (Schickel, 2021).

Literature review of QQ proposes two perspectives to QQ. One view of this phenomenon is that QQ is about setting work-life boundaries and not getting trapped in the daily hustle of unending deadlines and work pressure (Kilpatrick, 2022). The other view implies disengagement from work, making minimal efforts to just survive, and not displaying any passion towards work by not going the extra mile (Klotz and Bolino, 2022). When engagement of an employee with their work fades, EBO begins to set in, with positive feelings associated with engagement being replaced by negative ones. Exhaustion replaces energy, ineffectiveness replaces efficacy, involvement transforms into cynicism, perceived injustice replaces fair play, alienation replaces connectedness, and conflict replaces collaboration. These feelings resemble EBO (Maslach et al., 2001).

To understand QQ, it is important to comprehend the changing platform of the work-place. Long term employment is being replaced with temporary or contractual jobs, workplace relationships are no longer about families being connected, distrust has replaced loyalty, pyramid organizational hierarchies have metamorphosed into matrix type structures with multiple reporting authorities, organizational restructuring is rampant, and investors focus on immediate gratification instead of long term value building. In such a flexible work environment, it is unlikely that an employee will have any long term commitments with the organization. QQ also relates to unrealistic work demands and worker’s desire to avoid EBO (Khan et al., 2022). QQ leads to a knowledge loss, reduced productivity, absence of informal friendships, reduced customer loyalty, and thereby reduced revenues.

QQ has spread from corporates to academics (Morrison-Beedy, 2022), social workers (Scheyett, 2023), finance (Constantz, 2022; Serenco, 2024) among others. Quiet quitters limit their engagement to only what is required to be done as per the job description (Ford, 2023). EBO and disengagement have a higher probability of occurring when employees face high JD and are equipped with low JR (Bakker and de Vries, 2021). Tapper (2022) however, proposes that QQ protects employees from EBO, and that employees strive towards a better work-life balance by not expending additional effort. In addition to having a better work-life balance, QQ may also occur when employees feel disconnected from their work or workplace or do not trust their supervisors (Zenger and Folkman, 2022). The disconnection may occur when they are not updated about the developments of the organization or when they feel their opinions are not valued by the organization (Klotz and Bolino, 2022). Therefore, it would be logical to assume that employees working remotely are more likely to feel alienated as compared to the in-office colleagues, and thus would be more likely to engage in QQ (Anand and Ray, 2024). This study explores the moderating effect of JR and Grit on QQ.

Role of Job Resources and Grit

Job Resources

Schaufeli and Taris (2014) provided a definition for job resources (JR) as "positively valued aspects of the job, including physical, psychological, social, or organizational elements that aid in achieving work objectives, reducing JD, or fostering personal growth and development." JR are components within a job that facilitate professional advancement, enhance work engagement, and promote commitment to the organization (Demerouti and Bakker, 2011). The workplace provides avenues for employees to learn, grow, and achieve their objectives through JR, such as fostering a positive work environment, receiving support from supervisors and colleagues, and having autonomy in their roles (Crawford et al., 2010). JR aid employees in meeting their needs and shielding themselves from the strain imposed by certain JD.

JR play a crucial role in mitigating job stress and EBO (Bakker et al., 2007). In the delivery sector, JR can boost drivers' motivation and engagement, thereby preventing EBO, especially in context of high JD (Buitendach et al., 2016). Additionally, a study examining the working conditions of professional drivers found that those with less social support tend to experience higher rates of traffic violations and accidents (Useche et al., 2018).

Not many studies could be found by the authors that have employed the JD-R model to examine QQ behaviours among e-commerce delivery riders. However, prior research has established that job design influences employee performance while on delivery routes (Costantini et al., 2022), indicating that the JD-R framework can be a valuable tool for investigating the factors contributing to risky behaviours among e-commerce delivery workers.

If workers do not have the required resources, they are not able to cope with the pressing demands, and they would finally fail to achieve the goal. Demerouti et al. (2001) posited that EBO has two elements. The first one refers to the demands of work, which include workload, time related deadlines, contact with recipient, and the physical environment leading to exhaustion. The second element refers to absence of shortage of JR, such as timely feedback from supervisor, job security, autonomy, rewards, participation, and support from supervisor, leading to disengagement. The JD–R model proposes that JD are responsible for EBO, and that JR drives inspiration. This has been verified empirically (Demerouti et al., 2011). Supervisors play a key role in providing JR to their team members and thus play an important role in mitigating EBO. This study uses the symbolic interactions between supervisors and e-commerce delivery workers as an enabler of JR and examine JR’s moderating impact on the relationship between JD and EBO, as well as on the relationship between EBO and QQ.

Thus the first two hypotheses of this study are:

H1: Job Resources negatively moderates the relationship between Job Demands and Burnout.

H2: Job Resources negatively moderates the relationship between Burnout and Quiet Quitting.

Grit

In their examination of workplace deviance among front-line hospitality employees, Wu and Wei (2024) investigated the role of employee grit as a moderator. Previous studies have linked traits such as grit and hardiness (Frydenberg, 2017) to coping mechanisms in resilience research. Employee grit has been shown to impact job attitudes and performance (McGinley et al., 2020). Grit refers to a personality trait characterized by perseverance and passion, which drive individuals' determination and motivation to pursue long-term goals (Duckworth et al., 2007). It is a critical factor for individuals to achieve positive outcomes in resilience contexts (Frydenberg, 2017). Individuals with grit tend to persist in goals they are highly passionate about while abandoning those with low passion (McGinley et al., 2020). In the realm of sales and marketing, Schwepker and Good (2022) discovered that salespeople with grit are less prone to job stress because they interpret stress induced by stressors as industrious rather than debilitating. Front-line e-commerce employees who exhibit greater perseverance and passion in their roles are less likely to experience stress when confronted with ambiguity and conflict.

Passion towards the workplace can be developed in employees by their supervisors and leaders by rewarding favourable behaviour and timely feedback (Ho and Astakhova, 2018, 2020; Xiao et al., 2021). In this study, we use the symbolic interactions between the supervisors and e-commerce delivery workers as enablers of passion and thereby study the moderating effect of grit as a comprehensive construct on the relationship between JD and EBO, as well as on the relationship between EBO and QQ.

Thus, the next two hypotheses of this study can be written as:

H3: Grit negatively moderates the relationship between Job Demands and Burnout.

H4: Grit negatively moderates the relationship between Burnout and Quiet Quitting.

Theoretical Background and Conceptual Framework

Symbolic Interaction Theory

Symbolic interaction is among the various theories within the social sciences, asserting that facts are shaped by and through symbols. The basic tenet of Symbolic Interaction theory is that the facts are shaped by and through symbols. At its core, this theory emphasizes the significance of meanings. It explores the meanings that arise from the mutual interactions of individuals within social environments, delving into the question of "what symbols and meanings emerge from the interpersonal interactions?" However, symbolic interactionism, which views the individual as a social entity, has experienced a decline in dynamism since the 1970s. The contemporary iteration of symbolic interactionism differs substantially from the perspectives of Mead and Blumer, evolving into what Fine (1992) terms the "Post-Blumerist" era (Slattery, 2008). The theory of symbolic interaction has evolved with the contributions of thinkers such as Dewey (1930), Cooley (1902), and Mead (1934). While symbolic interactionists may differ in their perspectives, they unanimously agree that human interaction serves as the primary source of data. Additionally, there is a consensus among symbolic interactionists that perspectives and the ability to empathize are central to understanding symbolic interaction (Stryker & Vryan, 2003).

Schenk and Holman (1980) contend that symbolic interaction is dynamic as within this framework objects inherently carry meanings, and individuals mould their behaviours based on their self-assessments, as well as their perceptions of others and the objects in their surroundings. Thus, according to this viewpoint, it is the social actors who attribute meaning to objects.

The principal figure in the symbolic interactionist school is George Herbert Mead, a pragmatist and anti-dualist philosopher. Mead posits that the mind and ego are products of society, and he asserts that symbols are instrumental in the development of the mind and serve as tools for thought and communication (Ashworth, 2008). Mead's focus lies in examining how people engage in everyday interactions through symbolic means and how they establish order and significance in their lives (Korgen & White, 2008).

Blumer, a disciple of Mead, is credited with coining the term "symbolic interaction," making him also known as the pioneer of symbolic interactionism. As per Blumer (1980), humans attribute "meaning" in two distinct ways: (1) Meaning is ascribed to objects, events, phenomena, and so forth. (2) Meaning represents a "physical attachment" imposed on events and objects by humans. Blumer posits that meaning arises as a result of interactions among group members and is not an inherent quality of the object itself (Tezcan, 2005).

Consequently, meaning is generated through interpersonal interactions, enabling individuals to shape some of the realities comprising their sensory experiences. These realities are intertwined with the process of meaning formation. Hence, reality is comprised of the interpretation of various definitions. Thomas (1927) asserts that "the accuracy of interpretation is not crucial." He contends that reality is grounded in personal perceptions, which evolve over time.

In Blumer's symbolic interaction perspective, there are three fundamental principles: Meaning, language (which furnishes symbols for discussing meaning), and the thinking principle. This theory places meaning at the core of human behavior. Language assigns significance to humans through symbols. It's these symbols that distinguish human social relationships from animal communication. Humans attribute meaning to symbols and articulate these concepts through language, making symbols essential components of communication. In essence, symbols serve as the foundation for any communication act. The final principle in the symbolic interaction perspective is that thinking alters individuals' interpretations of symbols (Nelson, 2002).

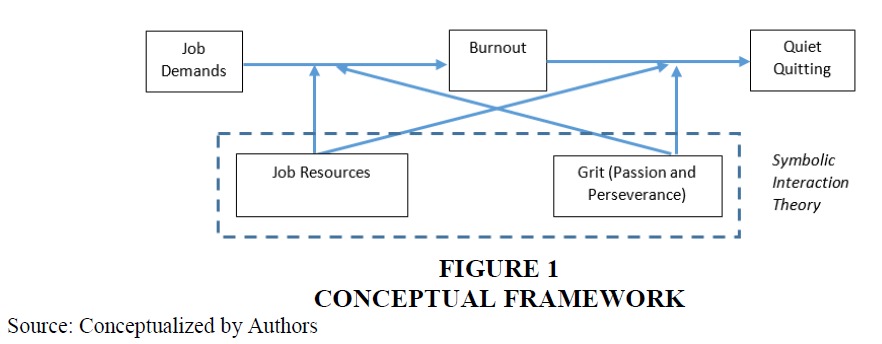

In this paper, symbolic interactions between the employee and their supervisor are contextual. These interactions are considered while examining the JR as well as while exploring grit. Items related to these interactions are included in the survey which was administered to the respondents of this study. It is important to study the symbolic interactions as they may occur multiple times in a single conversation. These may be team specific or organization specific, or these may be ritualistic, such as a gesture which the supervisor shares with the e-commerce delivery worker who completes their day’s target in the presence of other colleagues. The symbolic interactions may signal the provision of additional JR for the employee which in turn, may impact the relationship between JD and EBO, as well as EBO and QQ. The presence of symbolic interactions provides a high degree of motivation to the employee which in turn facilitates in enhancing the employee’s passion towards the workplace and therefore enhance grit, which in turn, may moderate the relationship between JD and EBO, as well as the relationship between EBO and QQ (Figure 1).

Methodology

Measures

To assess the workload aspects of job demand construct, the scale given by Pelfrene et al. (2001) was adapted, and to evaluate the emotional aspects of job demand, the scale provided by Aiello and Tesi (2017) was adapted for this study. To measure the time pressure related and work environment related JD, a scale given by Demerouti et al. (2001) was adapted. The scale given by Iwankicki and Schwab (1981) was adapted to measure EBO and a scale by Karrani et al. (2024) was adapted to measure QQ. JR was measured by using scales adapted from Cheung et al. (2021) and Demerouti et al. (2001). The scale provided by Wu and Wei (2024) was adapted to measure employee grit. Response categories followed a 5-point Likert scale in which 5 represented “Strongly Agree”, and 1 represented “Strongly Disagree”. The Likert scale was used to understand the degree to which the respondents agreed or disagreed with the items in the instrument.

Sampling and Data Collection

A survey was conducted across six weeks by circulating the instrument using WhatsApp to known individuals, who administered the survey. An orientation and training session was conducted for all the questionnaire administrators using zoom, for a duration of 40 minutes each. Some of the administrators were grouped together in one video session, while a few had to be instructed individual due to their specific availability at certain times of the day and certain days of the week. These known individuals acted as facilitators and presented the survey to the delivery workers and recorded their responses.

The target delivery workers included those who deliver groceries and wearables such as apparel, footwear, and accessories, for various platforms such as Amazon, Myntra, Flipkart, Ajio, TataCliq, BigBasket, and Blinkit among others. The facilitators were authorised to provide a small tip or incentive not more than 50 cents or INR 40 to the delivery workers for participating in this survey. The survey was administered to 431 e-commerce delivery workers, out of which 419 complete responses were received.

Non-food delivery workers from e-commerce were chosen for the sample, as this study had the context of e-commerce and food-delivery workers are generally perceived to be on the delicate intersection of e-commerce and hospitality.

Results

The Data was analysed using SmartPLS 4. EFA was not required since the constructs were taken from literature (Table 1).

| Table 1 Demographic Profile of Respondents | ||||

| N | Percentage (%) | Cumulative percentage (%) | ||

| Age | Less than 20 years | 75 | 17.9 | 17.9 |

| 21 to 25 years | 155 | 37.0 | 54.9 | |

| 26 to 30 years | 105 | 25.1 | 80.0 | |

| 31 to 35 years | 52 | 12.4 | 92.4 | |

| More than 35 years | 32 | 7.6 | 100.0 | |

| Gender | Female | 26 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Male | 393 | 93.8 | 100.0 | |

| Education level | Up to 10th standard | 21 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Up to 12th standard | 152 | 36.3 | 41.3 | |

| Diploma | 78 | 18.6 | 59.9 | |

| Graduate | 146 | 34.8 | 94.7 | |

| Post Graduate | 22 | 5.3 | 100.0 | |

| Work Experience | Less than 1 year | 26 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Between 1 to 2 years | 191 | 45.6 | 51.8 | |

| Between 2 to 4 years | 82 | 19.6 | 71.4 | |

| Between 4 to 6 years | 101 | 24.1 | 95.5 | |

| More than 6 years | 19 | 4.5 | 100.0 | |

The demographic profile of respondents is given in Table 1 below.

Measurement Model Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to assess convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The reliability of the constructs was identified by observing the factor loadings of all the constructs. A factor loading of 0.7 is considered acceptable (Kamboj & Rana, 2021) (Table 2).

| Table 2 Factor Loadings | |||||

| EBO | GP | JD | JR | ||

| EBO1 | 0.76 | ||||

| EBO3 | 0.91 | ||||

| EBO4 | 0.73 | ||||

| GPA1 | 0.95 | ||||

| GPA2 | 0.93 | ||||

| JDE1 | 0.72 | ||||

| JDT1 | 0.81 | ||||

| JDT2 | 0.80 | ||||

| JDW2 | 0.76 | ||||

| JRC1 | 0.84 | ||||

| JRC3 | 0.86 | ||||

| QQ5 | 0.81 | ||||

| QQ6 | 0.90 | ||||

| QQ9 | 0.92 | ||||

As per the results presented in Table 2 above, all the factor loadings obtained were greater than 0.7, indicating their dependability.

Before performing the structural analysis, the collinearity was evaluated leveraging the variance inflation factors (VIF) as suggested by (Hair et al., 2021). The results obtained for VIF metrics has been presented in Table 3.

| Table 3 Collinearity Statistics (Vif) – Outer Model | |

| VIF | |

| EBO1 | 1.512 |

| EBO3 | 2.115 |

| EBO4 | 1.511 |

| GPA1 | 2.452 |

| GPA2 | 2.452 |

| JDE1 | 1.425 |

| JDT1 | 1.573 |

| JDT2 | 1.503 |

| JDW2 | 1.563 |

| JRC1 | 1.241 |

| JRC3 | 1.241 |

| QQ5 | 1.748 |

| QQ6 | 2.478 |

| QQ9 | 3.063 |

As can be observed from the results presented in Table 2, multi-collinearity among the constructs was ruled out since the VIF values for the constructs were less than 4.

Structural Model Analysis

Following validation of the measurement model, the four hypotheses of this study were tested by examining the structural model.

The convergent validity of the measure was established. The discriminant validity assessment was established using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion, as given in Table 4 below. The values show that discriminant validity holds for this model.

| Table 4 Fornell and Larcker Criteria for Assessing Discriminant Validity | |||||

| EBO | GP | JD | JR | ||

| EBO | 0.804 | ||||

| GP | 0.201 | 0.940 | |||

| JD | 0.726 | 0.222 | 0.770 | ||

| JR | -0.680 | -0.170 | -0.690 | 0.849 | |

| 0.505 | 0.456 | 0.444 | -0.620 | 0.880 | |

The R square values show that 60.3 percent of variation in EBO is explained by the model and that 56.9 percent of the variation in QQ is explained by the model (Table 5).

| Table 5 R Square Overview | ||

| R-square | R-square adjusted | |

| EBO | 0.603 | 0.598 |

| 0.569 | 0.564 | |

The construct reliability and validity is explained in Table 6 below. The Cronbach’s alpha for EBO, Grit, JD, and QQ are reported above 0.7, which indicates that the items are sufficiently consistent to indicate that the measures are reliable (Shemwell et al., 2015). Griethuijsen et al. (2014) posited that Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.6 are also acceptable, therefore JR as a measure is also considered reliable.

| Table 6 Construct Reliability and Validity | ||||

| Cronbach's alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | Average variance extracted (AVE) | |

| EBO | 0.722 | 0.749 | 0.845 | 0.647 |

| GP | 0.870 | 0.906 | 0.938 | 0.883 |

| JD | 0.773 | 0.786 | 0.853 | 0.593 |

| JR | 0.612 | 0.613 | 0.837 | 0.720 |

| 0.850 | 0.875 | 0.909 | 0.769 | |

As the validity of the constructs was established, the structural model of this study was assessed to evaluate the hypotheses proposed in this study.

Cronbach’ alpha for the constructs was > 0.7 which depicted high internal consistency and therefore adequate reliability of the model.

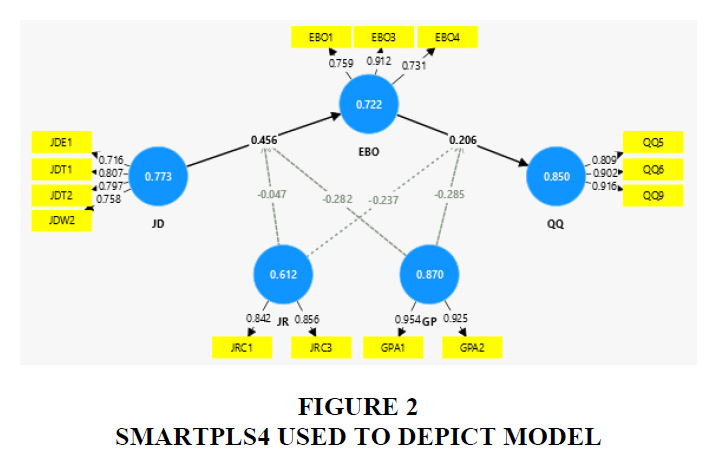

The factor loadings have revealed the items of each construct clearly. Items EBO1, EBO3, and EBO4 were clearly loaded with favourable values in the construct EBO. GPA1 and GPA2 had favourable loadings for Grit. The items JDE1, JDT1, JDT2, JDW2 were loaded in the construct JD. Items JRC1, JRS2, and JRS3 were loaded in favour of JR. Items QQ5, QQ6, and QQ9 were loaded in favour of the construct Quite Quitting. These items were then taken for creating the structural model in SmartPLS4. Structured equation modelling revealed the construct validity and reliability. Cronbach’s alpha for all constructs was > 0.7, as can be seen in Figure 1, which showed that there exists a high internal consistency in the model.

Moderation Analysis

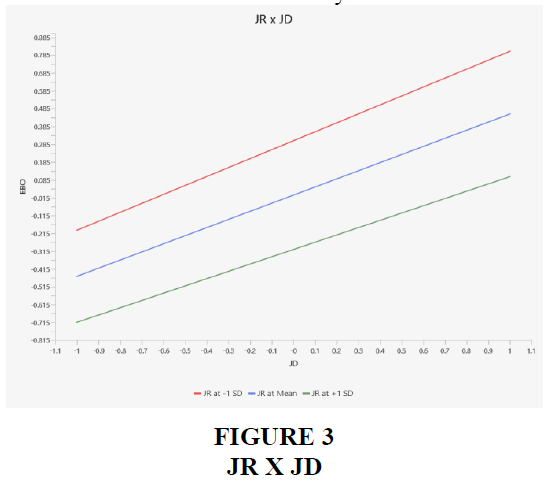

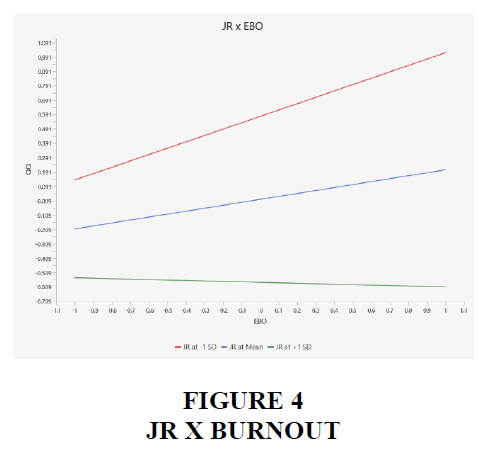

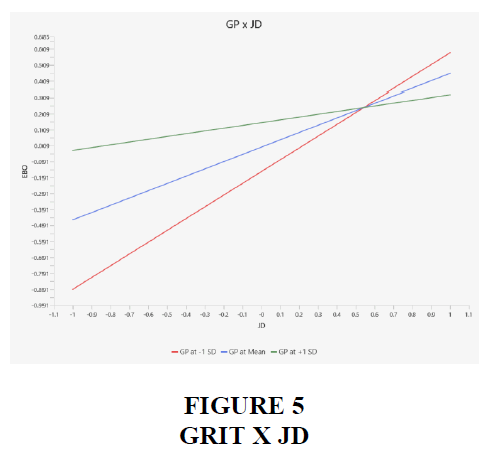

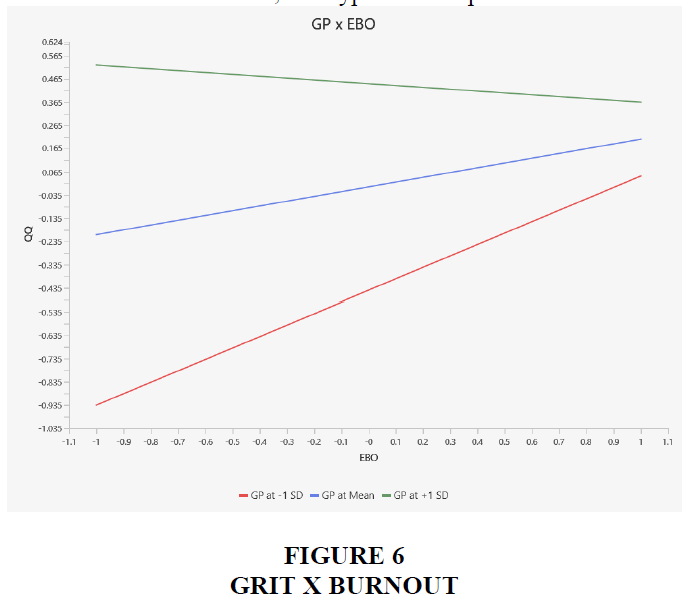

A slope analysis was conducted using the moderators, JR and Grit, to view their influence on the relationship between Job Demand and EBO as well as between EBO and QQ. The slope analysis showed the direction of influence on the relationship between these constructs and also depicted the direction and strength with which the relationship would be modified, if any influence was visible. These influences can be seen in Figures 2- 6.

A simple slope analysis is useful in investigating and interpreting significant interactions. Since this study is striving to understand the moderations effect of JR and Grit on the relationship between JD and EBO as well as the relationship between EBO and QQ, the simple slope analysis is a useful method for this study.

The moderation effect of JR on the relationship between JD and EBO was examined using the slope analysis. Figure 3 shows that the mean relationship between JD and EBO is a significantly positive one. This relationship is mildly reduced when the relationship is moderated by JR. This implies that JR has a mildly negative moderating effect on the relationship between JD and EBO. Thus, H1 hypothesis is proved.

The moderation effect of JR on the relationship between EBO and QQ was examined using the slope analysis. Figure 4 shows that the average relationship between EBO and QQ is a moderately positive one. This relationship is moderated by JR. This implies that when JR are increased, the impact of EBO on QQ decreases. However, we observe that when the JR are decreased, the impact of EBO on QQ increases significantly. Thus, H2 hypothesis is proved.

The moderation effect of Grit on the relationship between JD and EBO was examined using the slope analysis. Figure 5 shows that the mean relationship between JD and EBO is a significantly positive one. Grit has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between JD and EBO. Thus, H3 hypothesis is proved.

The moderation effect of Grit on the relationship between EBO and QQ was examined using the slope analysis. Figure 6 shows that the average relationship between EBO and QQ is a moderately positive one, when moderated by Grit. This relationship is moderately reduced when the relationship is moderated by Grit. This implies that when Grit, comprising of passion and perseverance are increased, the impact of EBO on QQ may reduce. However, we observe that when the employee Grit is reduced, the impact of EBO on QQ is significant. Thus, the absence or reduction in employee Grit leads to higher instances of QQ. Thus, H4 hypothesis is proved.

Discussion

This slope analysis reveals that though JR and Grit may be moderating the relationship between JD and EBO, the influence differs.

This study posits that in case JR are increased, the observed moderation of the relationship between JD and EBO is mild, but the moderation of the relationship between EBO and QQ is significant. However, in case Grit is increased, the observed moderation of the relationship between JD and EBO is moderate i.e. EBO may reduce moderately, but in case Grit is reduced, the moderation of the relationship between EBO and QQ is significant i.e. EBO and QQ will increase significantly.

To avoid EBO and QQ, organizations need to provide additional JR to their employees. The JR may be provided at three levels. The first level is the macro, or organizational level. The JR at this level could include improved salary, growth opportunities in the employee’s career, or job security which the organization can provide. The second level is the meso, or interpersonal and job level. The JR at this level include support and healthy working environment which co-workers can provide through collaboration at the workplace, support from the supervisor in terms of motivational symbolic interactional communication and inclusion in decision making, as well as clarity of role by supervisor. The emotional and psychological support by co-workers and supervisor at this level are important for the well-being of the employee. The third level is the micro, or the task level. The JR at this level includes autonomy, task significance, and feedback on performance of the employee, to enable timely correction (Demerouti and Bakker, 2011).

EBO and QQ can be avoided or minimized by organizations by developing Grit in their employees. Grit comprises of passion and perseverance. Passion may be developed by supervisors who act as enablers and help the employee identify with the organization, and develop a bond with it. The employees can also be motivated through demonstration of Grit at work by their supervisors, who may lead by example.

JR and Grit may be leveraged simultaneously to reduce EBO and QQ. Symbolic interactions can facilitate in developing Grit individually, while organizations can expedite the reduction of EBO and QQ through the provision of JR.

Organizations need to evolve multi-pronged strategies to overcome the problem of QQ. They will need to focus more on engaging with the employees and enhancing their engagement with the organization. Organizations will need to consciously improve the work life balance of delivery employees who are continually under the pressure of time to delivery on time, every time. This will need to be done in coordination with customers and making them aware of the working conditions of the delivery workers.

Communication between supervisor and employees needs to improve. Supervisors may need to be trained on the symbolic interaction theory, as their symbolic communication is regarded as highly by the employees as their written or verbal communication. Often, the symbolic interaction is more important in motivating employees as compared to the spoken word. Symbolic interactions can occur multiple times in a single conversation and a supervisor who is aware of this can directly contribute to enhancing the employee’s grit, which in turn is key in moderating the relationship between EBO and QQ.

Identifying supervisors who are good at symbolic interaction and leveraging them to train others could help improve the organization’s productivity. Employees who have high degree of passion and perseverance, may be rewarded or promoted to exemplify the importance which the organisation attaches to symbolic interactions. This will also help build a positive culture and transform the team from being Quiet Quitters to vociferous advocates of the organization.

Implications

Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of this study impact literature related to understanding the antecedents of QQ and the moderators thereof. The findings imply that the relationship between JD and EBO is moderated by JR and Grit to a certain extent. JR is observed to have a larger moderating effect on the relationship between EBO and QQ as compared to its moderating effect on the relationship between JD and EBO. A larger impact of moderators may be seen on the relationship between EBO and QQ. The analysis shows that Grit, which comprises of passion and perseverance, has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between JD and EBO as well as the relationship between EBO and QQ, which implies that Grit is of significant importance in reducing the impact of JD on EBO and the impact of EBO on QQ.

Practical Implications

The practical implications of this study are important for human resource managers, team leaders and senior management of organizations. This study helps understand that by enhancing JR, it may be possible to reduce EBO. Enhancing JR may also enable a reduction in QQ due to EBO, to a certain extent. However, increasing Grit may have a more significant influence on reducing EBO and QQ.

In case human resources, team leaders and senior management are able to develop passion in the employees about their jobs, their workplace, and their organization, this could help reduce EBO as well as QQ, thereby avoiding loss of productivity of the organization. In case they are unable to increase employee’s Grit, at the very least, they should definitely avoid in a reduction of Grit in employees, as a reduction would have severe negative consequences in terms of increasing EBO and QQ significantly.

While this research has been conducted in the context of e-commerce delivery workers, the findings may be generalizable in organizations across other sectors as well.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study is not without limitations. The respondents of this study were limited to the northern region of India. It is recommended that future scholars may extend this study to different geographies to generalize the findings or to find peculiarities in different regions and variations in findings due to cultural differences. A second limitation of this study is that this study only used quantitative method, which may not address the nuances related to QQ. Future research may include qualitative feedback from the delivery workers which would enhance the robustness of the findings. A third limitation is that this study only targeted respondents who delivered groceries, apparel, footwear and accessories. Future studies may also include delivery employees who deliver food, and other products, such as couriers to understand a wider perspective. A fourth limitation is that this study focused only on EBO as an antecedent to QQ, since this was the predominant antecedent in literature. Future scholars are recommended to assess other antecedents to QQ and study moderation of their relationship with QQ.

Conclusion

This study used literature to link JD with EBO and further EBO with QQ. It proposed the moderating effect of JR and Grit on the relationship between JD and EBO as well as on the relationship between EB and QQ. This study analysed the responses from e-commerce delivery workers on constructs of JD, EBO, QQ, JR, and Grit. SmartPLS 4 was used to empirically understand the influence of moderators on the relationship between JD and EBO as well as on the relationship between EBO and QQ.

The study found that the relationship between JD and EBO is moderated to a mild extent by the presence or absence of JR and the relationship between EBO and QQ is moderated to a moderate extent by the presence of JR. However, the relationship between EBO and QQ is moderated to a significant extent by the absence of JR. This study also found that the relationship between JD and EBO is moderated to a significant extent by the presence as well as absence of Grit.

This study contributes to literature by examining the moderating effect of JR and Grit on the relationship of QQ with its antecedents. The practical contribution of this study is the suggestion to develop employee grit, to avoid burnout and reduce the incidence of quiet quitting.

To the best of the knowledge of the authors, this study is the first such study conducted on the phenomenon of quiet quitting by delivery workers in e-commerce.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors hereby declare that there are no competing interests.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Funding for this research was covered by the author(s) of the article.

References

Aiello, A., & Tesi, A. (2017). Emotional job demands within helping professions: psychometric properties of a version of the Emotional Job Demands scale. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 24(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Aksan, N., K?sac, B., Ayd?n, M., & Demirbuken, S. (2009). Symbolic interaction theory. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 902-904.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anand, A., Doll, J., & Ray, P. (2024). Drowning in silence: a scale development and validation of quiet quitting and quiet firing. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(4), 721-743.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ashworth, P. (2008). Conceptual foundations of qualitative psychology. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods, 2, 4-25.

Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, stress, & coping, 34(1), 1-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands?resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 43(1), 83-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of educational psychology, 99(2), 274.

Blumer, H. (1980). Mead and Blumer: The convergent methodological perspectives of social behaviorism and symbolic interactionism. American Sociological Review, 409-419.

Boamah, S. A., Hamadi, H. Y., Havaei, F., Smith, H., & Webb, F. (2022). Striking a balance between work and play: The effects of work–life interference and burnout on faculty turnover intentions and career satisfaction. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(2), 809.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Buitendach, J. H., Bobat, S., Muzvidziwa, R. F., & Kanengoni, H. (2016). Work engagement and its relationship with various dimensions of work-related well-being in the public transport industry. Psychology and Developing societies, 28(1), 50-72.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carmichael, G. S. (2022). Quiet quitting is the fakest of fake workplace trends.

Chai, L. T., & Yat, D. N. C. (2019). Online food delivery services: Making food delivery the new normal. Journal of Marketing advances and Practices, 1(1), 62-77.

Chen, C. F., & Kao, Y. L. (2013). The connection between the hassles–burnout relationship, as moderated by coping, and aberrant behaviors and health problems among bus drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 53, 105-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cherniss, C. (1980). Evaluation and action in the social environment. Evaluation and Action in the Social Environment, 125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cheung, C. M., Zhang, R. P., Cui, Q., & Hsu, S. C. (2021). The antecedents of safety leadership: The job demands-resources model. Safety Science, 133, 104979.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chung, Y. S., & Wu, H. L. (2013). Effect of burnout on accident involvement in occupational drivers. Transportation research record, 2388(1), 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cieniewicz, A. (2023). Commitment Profiles of Federal Government Employees Who Telework: A Qualitative Study Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning. (Doctoral thesis). The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University.

Constantz, J. (2022). Quiet Quitting Surges in Finance as it Gains Steam Across Sectors, Bloomberg.

Costantini, A., Ceschi, A., & Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. (2022). Eyes on the road, hands upon the wheel? Reciprocal dynamics between smartphone use while driving and job crafting. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 89, 129-142.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 01-09.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied psychology, 86(3), 499.

Dewey, John 1930 Individualism, Old and New. New York: Minton, Balch and Co.

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2004). Customer-related social stressors and burnout. Journal of occupational health psychology, 9(1), 61.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 92(6), 1087.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fine, G. A. (1992). Agency, Structure, and Com parat ive Con texts: Toward a Synthetic lnteractionism. Symbolic Interaction, 15(1), 87-107.

Fisher, D. G., Hageman, A. M., & West, A. N. (2023). Academic burnout among accounting majors: The roles of self-compassion, test anxiety, and maladaptive perfectionism. Accounting Education, 1-25.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ford, J. S. (2023). The early-career sabbatical: a bridge over the widening chasm of physician burnout. Academic Medicine, 98(7), 757.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Formica, S., & Sfodera, F. (2022). The Great Resignation and Quiet Quitting paradigm shifts: An overview of current situation and future research directions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 31(8), 899–907.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

Frydenberg, E., & Frydenberg, E. (2017). Positive psychology, mindset, grit, hardiness, and emotional intelligence and the construct of resilience: A good fit with coping. Coping and the Challenge of Resilience, 13-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Goh, E., & Baum, T. (2021). Job perceptions of Generation Z hotel employees towards working in Covid-19 quarantine hotels: the role of meaningful work. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1688-1710.

Golembiewski, R. T., Munzenrider, R. F., & Stevenson, J. G. (1985). Profiling acute vs chronic burnout, I: Theoretical issues, a surrogate, and elemental distribution. Journal of Health and Human Resources Administration, 107-125.

Gribben, L., & Semple, C. J. (2021). Factors contributing to burnout and work-life balance in adult oncology nursing: an integrative review. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 50, 101887.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Griethuijsen, R. A. L. F., Eijck, M. W., Haste, H., Brok, P. J., Skinner, N. C., Mansour, N., et al. (2014). Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Research in Science Education, 45(4), 581–603.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., Ray, S., ... & Ray, S. (2021). Evaluation of formative measurement models. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 91-113.

Halbesleben, J. R., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: the mediating role of motivation. Journal of applied psychology, 92(1), 93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hamouche, S., Koritos, C., & Papastathopoulos, A. (2023). Quiet quitting: relationship with other concepts and implications for tourism and hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(12), 4297-4312.

Harter, J. (2022). Is Quiet Quitting Real? Gallup, Workplace.

Ho, V. T., & Astakhova, M. N. (2018). Disentangling passion and engagement: An examination of how and when passionate employees become engaged ones. Human Relations, 71(7), 973-1000.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ho, V. T., & Astakhova, M. N. (2020). The passion bug: How and when do leaders inspire work passion?. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(5), 424-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Holden, S. (2018). Professional Identity, Commitment, and Intent to Persist: The Facilitative Role of Mindfulness for Pre-Service Teachers. The University of Memphis.

Iwanicki, E. F., & Schwab, R. L. (1981). A cross validation study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educational and psychological measurement, 41(4), 1167-1174.

Kamboj, S., & Rana, S. (2023). Big data-driven supply chain and performance: a resource-based view. The TQM Journal, 35(1), 5-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kandampully, J. (2006). The new customer?centred business model for the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(3), 173-187.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kang, J., Kim, H., & Cho, O. H. (2023). Quiet quitting among healthcare professionals in hospital environments: a concept analysis and scoping review protocol. BMJ open, 13(11), e077811.

Karatepe, O. M., & Tekinkus, M. (2006). The effects of work-family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and intrinsic motivation on job outcomes of front-line employees. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 24(3), 173–193.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Karrani, M. A., Bani-Melhem, S., & Mohd-Shamsudin, F. (2024). Employee quiet quitting behaviours: conceptualization, measure development, and validation. The Service Industries Journal, 44(3-4), 218-236.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khan, K. S., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., & Ullah, I. (2022). The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. International journal of mental health and addiction, 20(1), 380-386.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kilpatrick, A. (2022). What is “quiet quitting” and how it may be a misnomer for setting boundaries at work. NPR. Retrieved August, 29, 2022.

Klotz, A., Bolino, M. (2022). When Quiet Quitting Is Worse Than the Real Thing. Managing Employees. Accessed on 4 June 2024.

Korgen, K. & J.M. White (2008). Engaged sociologist: connecting the classroom to the community. Pine Forge Press.

Lai, P. L., Jang, H., Fang, M., & Peng, K. (2022). Determinants of customer satisfaction with parcel locker services in last-mile logistics. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 38(1), 25-30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lord, J. D. (2022). Quiet quitting is a new name for an old method of industrial action. The Conversation.

Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2006). Take this job and…: Quitting and other forms of resistance to workplace bullying. Communication monographs, 73(4), 406-433.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maslach, C. (1978). The client role in staff burn?out. Journal of social issues, 34(4), 111-124.

Maslach, C. (2011). Burnout and engagement in the workplace: New perspectives. European Health Psychologist, 13(3), 44-47.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2017). Understanding burnout: New models. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice, 36-56.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

McGinley, S., Mattila, A. S., & Self, T. T. (2020). Deciding to stay: A study in hospitality managerial grit. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(5), 858-869.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mead GH. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press.

Morrison-Beedy, D. (2022). Are We Addressing “Quiet Quitting” in Faculty, Staff, and Students in Academic Settings? Building Healthy Academic Communities Journal, 6(2), 7-8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nelson, K., & Shaw, L. K. (2002). Developing a socially shared symbolic system. In Language, literacy, and cognitive development (pp. 39-72). Psychology Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pelfrene, E., Vlerick, P., Mak, R. P., De Smet, P., Kornitzer, M., & De Backer, G. (2001). Scale reliability and validity of the Karasek'Job Demand-Control-Support'model in the Belstress study. Work & stress, 15(4), 297-313.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pevec, N. (2023). The concept of identifying factors of quiet quitting in organizations: an integrative literature review. Challenges of the Future, 2, 128-147.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ratnatunga, J. (2022, March 16). Quiet Quitting: The Silent Challenge of Performance Management.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 43–68). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schenk, C. T., & Holman, R. H. (1980). A Sociological Approach to Brand Choice: The Concept of Situational Self Image. Advances in consumer research, 7(1).

Scheyett, A. (2023). Quiet quitting. Social Work, 68(1), 5-7.

Schickel, E. (2021). Remote work and the Covid-19 pandemic: an assessment of work-related outcomes in remote work before and during the pandemic.

Schwepker Jr, C. H., & Good, M. C. (2022). Salesperson grit: Reducing unethical behavior and job stress. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 37(9), 1887-1902.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Serenko, A. (2024). The human capital management perspective on quiet quitting: recommendations for employees, managers, and national policymakers. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(1), 27-43.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shemwell, J. T., Chase, C. C., & Schwartz, D. L. (2015). Seeking the general explanation: A test of inductive activities for learning and transfer. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(1), 58-83.

Shumate, M., & Fulk, J. (2004). Boundaries and role conflict when work and family are colocated: A communication network and symbolic interaction approach. Human Relations, 57(1), 55-74.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, J. (2000). Performance productivity and quality of frontline employees in service organizations. Journal of marketing, 64(2), 15-34.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Slattery, B. (2008). Conceptualising and modelling hierarchical classification from. In International Conference of Applied Behaviour Analysis (Chicago, USA).

Stryker, S., & Vryan, K. D. (2003). The symbolic interactionist frame. Handbook of social psychology, 3-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tang, C. S. K. (1998). Assessment of burnout for Chinese human service professionals: A study of factorial validity and invariance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(1), 55-58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tapper, J. (2022). Quiet quitting: why doing the bare minimum at work has gone global. The Guardian, 6.

Tezcan, M. (2005). Sosyolojik kuramlarda egitim. Ankara: Ani Yayincilik.

Thomas, W. I. (1927). The behavior pattern and the situation. Publications of the American sociological society, 22, 1-14.

Useche, S. A., Cendales, B., Montoro, L., & Esteban, C. (2018). Work stress and health problems of professional drivers: a hazardous formula for their safety outcomes. PeerJ, 6, e6249.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wade, J. (2022). Loud and quiet quitting: the new epidemic isn’t just a trend. Forbes. https://www. forbes. com/sites/forbesbooksauthors/2022/09/26/loud-and-quiet-quitting-the-new-epidemic-isnt-just-a-trend.

Wilkinson, L. (2022). Adapting to Meet the Challenges of Post-Pandemic Employee Engagement. (Doctoral thesis). The College of St. Scholastica, Duluth, MN

Wu, A., & Wei, W. (2024). Rationalizing quiet quitting? Deciphering the internal mechanism of front-line hospitality employees’ workplace deviance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 119, 103681.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Xiao, Y., Liu, S., & Dai, T. (2021). Positive and negative supervisor development feedback, team harmonious innovation passion and team creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 681910.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Y?k?lmaz, ?. (2022). Quiet quitting: A conceptual investigation. Anadolu 10th International Conference on Social Science, 581-591.

Y?ld?z, S. (2023). Quiet quitting: Causes, consequences and suggestions. International Social Mentality and Researcher Thinkers Journal (SMART JOURNAL).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Berry, L.L. (1990).Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations. The Free Press, New York, NY

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zenger, J. and Folkman, J. (2022), Quiet quitting is about bad bosses, not bad employees. Harvard Business Review.

Received: 24-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15087; Editor assigned: 25-Jul-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15087(PQ); Reviewed: 26- Aug-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15087; Revised: 26-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15087(R); Published: 16-Oct-2024