Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 6S

Prospects and Challenges for Iraqi SMES Sector Post-Isis

Yousif Aftan Abdullah, University of Baghdad

Abstract

Iraq faces significant economic challenges, owing in part to its reliance on oil revenue and the country's overburdened public sector. The supremacy of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), obstructive rules, a lack of access to finance, a shortage of skilled labor, and inadequate infrastructure all impede private sector growth. This research relied mainly on information from global development organizations, most markedly the World Bank, as well as policy documents, and it discovered a scarcity of pertinent educational writings. The following are the key findings of this research: Recent economic growth has not resulted in poverty reduction; the stretched history of war and insecurity in Iraq has hampered progress and development; the private sector is critical to creating jobs and promoting long-term growth; State-Owned Enterprise (SOEs) dominance; the bloated, inefficient government sector; laws and regulations impede the development of the private sector; and difficulties in obtaining financing. Future prospects to promote inclusive and long-term growth through SMEs sector in Iraq are also discussed in the paper.

Keywords

Economic Challenges, SOE’s, State Owned Enterprises, Development, Iraq

Introduction

Political Instability, Wars and Conflict

Political instability, wars and conflicts have had an enormously negative influence on economic development and improvement of Iraq.

History

Iraq's history is rife with conflict, insecurity, and upheaval. For three decades, it was ruled by the Ba'ath Party, which was a total autocracy marked by extra-judicial slayings, forced disappearances, anguish, and other severe human rights desecrations (WB, 2017). Despite this, the country did well on several developmental and prosperity indicators: before 1991, healthcare sector covered approximately 97 percent of the metropolitan populace and 79 percent of the countryside population; a probable 90 percent of the people had right to clean drinking water; and child mortality rate was 29 per 1,000 in 1989 (WB, 2017). Subsequently, the Iran-Iraq war, which lasted from 1980 to 1988, not only resulted in massive casualties but also had serious economic consequences. The war areas involved key oil manufacturing and distributing plants in the south of Iraq, resulting in significant destruction and the cancellation of oil expansion plans. Simultaneously, the economic base of Iraq shrank as defense and food importations were prioritized. However, rather than collapsing, growth stalled during this time period.

With the invasion of Kuwait in 1991, this all changed. As oppose to the Iran-Iraq war, in which Iraq received widespread international support, Iraq's attack on the Kuwait was unanimously condemned (Krishnan et al., 2014). Additionally, the force led by US that sent Iraq forces out of Kuwait followed the Iraq army into the southern part of Iraq, instigating even more devastation. After Iraq invaded Kuwait, the UN imposed a stringent sanctions regime that lasted until 2003. During the sanctions era, the non-oil business and agriculture suffered an overwhelming drop: cereal production in 2000, for example, was roughly one-quarter of what it had been in 1990 (WB, 2017).

Assumed that the restrictions were explicitly planned to make it difficult for the administration to provide basic necessities, it is not unexpected that the country's growth indicators weakened considerably. Poverty and child death rates increased rapidly; per capita GDP decreased to USD 174 by 1994, from a projected USD 2,836 in 1989 (WB, 2017).

Post-2003 Period

After the US led incursion in 2003, the country experienced quickly failing security situation in 2004 and a factional civic war in 2005-06. This was timed to coincide with an increase in oil revenues. The government was unable to pay attention to restoration, particularly for vulnerable structure for example energy and water, or to resolve long-lasting and accruing sector complications such as agrarian decline, due to the security situation. Simultaneously, ‘a new stratum of dislocation and inner city disintegration was included to preceding incidents' (Krishnan et al., 2014). Economic growth and expansion, which require such rudimentary infrastructure, were thus halted until some appearance of permanency could be reinstated (Krishnan et al., 2014). In its place, the government prioritized security expenditure and job creation in the public sector, as well as pay raises, in order to maintain public trust.

ISIS Conflict

In 2014, there was yet another fight with ISIS. It should be noted that the ISIS conflict and pervasive uncertainty destroyed infrastructure and properties in the areas controlled by ISIS and averted resources from industrious ventures. It also leads to significant impact on private sector consumption and investment confidence, increased vulnerability, poverty, and joblessness. When compared to the rest of the country, the unemployment rate in the governorates most affected by ISIS is roughly twice as high (21.6 percent vs. 11.2 percent). At the end of 2017, the conflict's aggregate real damages amounted to 72 percent of 2013 GDP and 142 percent of 2013 non-oil GDP.

Economic History of Iraq

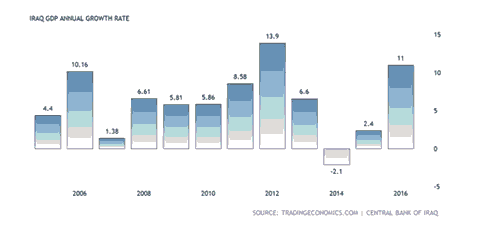

GDP growth rate of Iraq has been volatile in contemporary time period, ranging from 5.8 percent in 2009 to 13.9 percent in 2012 before falling to 0.7 percent in 2014. It rose in 2016, hitting 11 percent, but fell to 0.8 percent in 2017 as a result of a 3.5 percent fall in oil production to fulfill OPEC criteria.

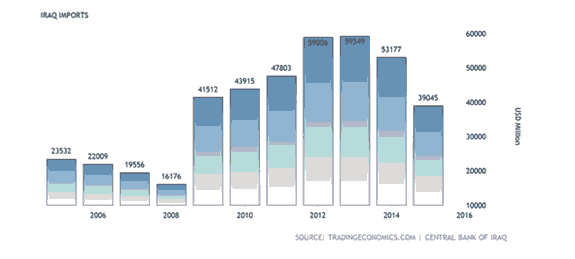

Due to increasing oil prices and initiatives to control current spending, the fiscal deficit is expected to decrease to 2.2 percent of GDP in 2017. In 2017, overall public debt was predicted to have fallen to 58 percent of GDP, attributable to both of these reasons. Current account deficit is expected to rebound to a surplus of 0.7 % of GDP in 2017. Also, current account deficit is expected to rebound to a surplus of 0.7 percent of GDP in 2017. Foreign reserves, on the other hand, financed the majority of the balance of payment deficit, falling from USD 77.8 billion at the end of 2013 (roughly 10 months' worth of imports) to USD 48.1 billion at the end of 2017.

The macroeconomic viewpoint in Iraq is likely to improve as a result of improved security, higher oil prices, and a gradual increase in reconstruction investment (World Bank, 2018). Subsequent to the complete release of all Iraqi land from ISIS in December of 2017, the government of Iraq is putting in place an inclusive renovation package that connects instant steadiness to a longstanding goal and begins the retrieval and rebuilding process.

Impoverishment

Between 2007 and 2012, Iraq made some progress in reducing poverty, but the most

recent figures indicate the reverse pattern. Also, poverty (defined as the people living under the national poverty line) augmented from 18.9 percent in 2012 to an approximate 22.5 percent in 2014 (WB, 2018). It is important to note that the meek decrease in poverty between 2007 and 2012 was supplemented by increasing inequality: per capita consumption of Iraq became faster for the rich people than for the underprivileged ones (WB, 2017). Multidimensional poverty of Iraq is projected to be 35% (WB, 2017), which increased from 11.6 percent in 2011 (Rohwerder, 2015). From the numerous factors making contribution to this, poor sustenance, lack of cleanliness, and scarce electricity are among the most prevailing problems (WB, 2017).

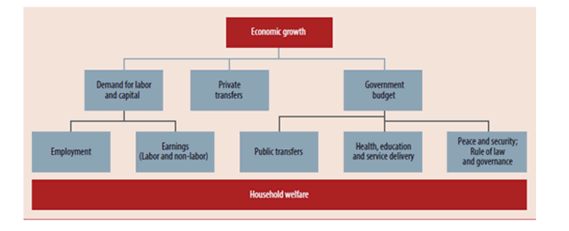

World Bank claims that modest poverty decline despite robust economic progress proposes that the relationship between development, employment, and income is weak (Krishnan et al., 2014). Between 2007 and 2012, the decline in headcount poverty was due to a rise in income among the working class, and not because of an upsurge in employment or greater public transfers (WB, 2017). Economic development is not linked with employment creation in the private sector, where most of the underprivileged people go for work (WB, 2017). War and violence, as well as oil dependency, are major contributors to Iraq's rising poverty.

Furthermore, joblessness in Iraq has increased, predominantly among the underprivileged families, young people, and those between the working age of 25 and 49 (WB, 2018). The joblessness ratio in the areas most affected by ISIS-related violence and dislocation is approximately double that of the rest of the country (21.1 percent vs. 11.2 percent), mainly among the youth and illiterate people (WB, 2018). The joblessness ration among the 3 million internally displaced people is 55 percent greater than in host populations (WB, 2018).

Disparity

Iraq's progress and growth situation is full of significant spatial differences. Traditionally, poverty has remained focused in the south region and central region of Iraq. However, between 2007 and 2012, poverty ratio in the southern regions also increased by 1.8 percent (WB, 2017). On the other hand, it decreased by 16 percent in the central regions and by 9 percent in the northern regions.

Furthermore, there are much noteworthy rural and urban dissimilarity in poverty ratios, which means that there is more poverty in rural, less-populated and far-off areas than urban areas where most of the people are poor due to the huge population size (Rohwerder, 2015). A range of factors contribute to longitudinal disproportions in poverty ratios and poverty decline, comprising the circulation of oil riches, differences in post-2003 stability and security, the post-2014 impact of ISIS, and continued negligence of the southern regions (Krishnan et al., 2014).

Additionally, poverty ratio differs according to demographic characteristics and is greater among certain marginalized classes, in addition to spatial discrepancies. It is considerably greater in big families: a typical poor household is bigger (more than 10 family members) and has more dependent people than a non-poor family (WB, 2017). Furthermore, the heads of poor families have lesser levels of schooling than heads of non-poor families. Poor people are mainly working in the private sector, such as farming, construction, business, and transport, while, almost 40 percent of the non-poor are working in commerce, finance, or public administration (WB, 2017).

Limitations for Private Sector of Iraq

The Importance of Fostering Private Sector

Individual, micro, and small businesses dominate Iraq's private sector, which is primarily engaged in merchandising and trade, transportation and construction services, and electric sector (RoI, 2014). Most of the businesses are individual proprietorships, with the rest being mostly family partnerships: the country has limited number of multi-industry and big corporations. Big private companies, on the other hand, are evolving in ICT, especially manufacturing, technical facilities for gas and oil division, and mobile communications (RoI, 2014; WB, 2017). Production in the private segment differs: in textiles and garments, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, non-metals, and equipment, Iraqi private firms outperform others in the MENA region; in food processing and electronics, however, productivity is relatively low (WB, 2012; RoI, 2014).

The literature acknowledges that Iraq must decrease its dependence on oil and improve its private segment. Economic branching out is critical, and it must be led by an invigorated countrywide private segment (RoI, 2014). Private segment is considered as critical to employment generation and conflict resolution. ‘Active delivery of rudimentary services and the foundation of employment generating prospects, particularly for young people in newly liberated regions, are necessary to ease the core instability and prevent a new phase of conflict and war in the country' (WB, 2018).

On the other hand, there are many obstructions to private segment expansion. In addition to the common limitations to economic progress in Iraq discussed earlier, there are others that are particularly relevant to and have an impact on the private sector.

State-Owned Enterprise Dominance

The public sector's dominance in the economy of Iraq has disallowed the advent of a thriving private segment and the accompanying employment creation which is necessary to increase the wellbeing of the people of Iraq (WB, 2017). State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) have worked as bases of support for previous Iraqi governments, allowing them to maintain control over the sectors in question (Tabaqchali, 2017). Most non-oil private firms have been pushed out by SOEs (along with a jumble of rules that obstructs market activity) (WB, 2017).

Agriculture is one area where the constant supremacy of SOEs had a substantial destructive effect. Iraq's cereal manufacturing in 2000 was roughly one-quarter of what it was in 1990 (Krishnan et al., 2014). While many issues had been present for some time, the agriculture division was afflicted by an absence of availability of acute inputs, particularly seeds, throughout the 1990s. The agricultural input activities were focused in the proximity of Baghdad (to assist regime dominance): this was demonstrated as a major weakness in the beginning of 2003, when instability disturbed supply chains in the country, divesting many regions of critical agrarian input (Krishnan et al., 2014).

Challenges to Reform

Since the 1990s, many state-owned enterprises have gone bankrupt (Krishnan et al., 2014). Although SOE transformation has been deliberated for several years, only partial noticeable improvement has been made (WB, 2017). Isolation of Iraq after the assault on Kuwait destined that there was not any interior or exterior stimulus for private segment transformation (such as WTO membership). Subsequent Saddam Hussain's ouster and increase in oil proceeds in the 2000s, the government's lack of appetite for major SOE reform was exacerbated by the country's poor security and stability.

In any case, reforming SOEs is a huge responsibility: according to the World Bank, 37 percent of Iraq's total estimated SOE employees are redundant (WB, 2012). According to IMF, approximately 176 SOEs employ more than 555,000 individuals, out of which 30 percent to 50 percent are extra vacancies, and the majority of SOEs are considered as not functional (Tabaqchali, 2017). Although keeping them open requires resources, administration cannot close them because of the substantial social cost, and denationalizing them while upholding employment is a difficult circle to square (Tabaqchali, 2017). Due to the difficulties in transformation, World Bank considers that, at least in the short time span, inner reformation of sustainable SOEs to increase their capacity to fulfill their obligations is more socially and politically achievable than shutting or denationalization (WB, 2017).

Regulatory Framework

The regulatory situation in Iraq is unfavorable to the private segment. According to the Private Sector Development Strategy of government from 2014-2030, "current laws and regulations governing the private sector frequently act as an impediment to private sector development." In many cases, they are hindering the revival of the private segment and stopping the generation of new employment opportunities (RoI, 2014).

Stringent Private-Sector Regulations

The World Bank identifies three ways in which regulations can stymie private-sector businesses: I when regulations are applied but are unnecessary; (ii) when necessary regulations are poorly designed; and (iii) when regulations are poorly applied and administered – all of which it claims apply to Iraq (WB, 2017). Many of the country's 29,000 laws and regulations were enacted in the previous century, but when new laws were enacted, the old ones were not repealed. As a result, the Iraqi legislative system is burdened with a heavy legacy of antiquated legislation that works against the country's need for an open, transparent, and diverse economy (WB, 2017). Moreover, regulations are frequently poorly designed, and their impact on the private sector is not adequately considered; existing laws are poorly enforced; there is no effective and cohesive coordination among the various ministries regulating the private sector or between the government and the private sector; and many ministries lack the capacity to implement any reform (WB, 2017).

In an overall environment of very little structural policy reform, private sector development is one of the weakest reform areas: in 2018, Iraq ranked 154 for starting a business (up from 169 in 2014) and 168 for resolving insolvency because it is not possible to legally close a business (Krishan et al., 2014; WB, 2018b). Iraq's overall ease of doing business ranking in the 2018 report is 168 (out of 190), (WB, 2018b), but it improved 17 points in terms of obtaining electricity and 14 points in terms of registering a property (Hadad, 2018). There are also currently long delays in transferring large sums of money into and out of Iraq, which discourages foreign investors.

Availability of Finance

Iraq's financial sector is controlled by the government and there is no competition, and therefore, is incapable to encounter the requirements of an emerging private economy (WB, 2012). The monetary segment is insignificant as compared to the GDP of Iraq and is ruled by banks, holding more than 75 percent of resources (WB, 2012). The investment system is controlled by state banks, accounting for roughly 90 percent of total resources and securities, mainly from the government and SOEs (Tabaqchali, 2017). This is because of legislature demanding the SOEs and government to hold financial records and credits only with state banks, to admit cheques dispensed by state banks only, and to limit salary and pension payments to state banks (Tabaqchali, 2017). The linkage to SOEs and the complications in improving them also reinforces the state's dominance of the banking sector. Despite their (SOEs') insolvency, the regime could depend on the two state-owned banks, Rashid and Rafidain, both of them are in receivership, to offer to the SOEs for employees sponsoring (Krishnan et al., 2014). As a result, this guaranteed continuous state supremacy of the financial subdivision, since financial subdivision reformation would have created the problem of extensive SOE transformation (Krishnan et al., 2014). The commercial banking segment has approximately 40 percent of private segment loans and deposits; however it has shortage of the capital and groundwork to become a loan expansion instrument (Tabaqchali, 2017).

Future Prospects

After the review of the literature and the limitations to wide-ranging, sustainable development - particularly private sector development - the below areas for improvement appear:

Diversification

It is important for Iraq to diversify its economy and decrease its dependence on gas and oil proceeds. It should capitalize more in production and agriculture, in particular, to increase local employment creation, decrease its reliance on importations, and increase its long-standing economic projections.

Gas and Oil manufacturing

It is critical that the government of Iraq keeps on prioritizing investment in gas and oil sector while also working to improve the competence of the institutes that contract with overseas corporations working in the area. These means are the foundation of the economy of Iraq, and a transition away from oil reliance will require their effective deployment. Agreements with oil firms could be renegotiated to make this more controllable. The government could also benefit from abandoning its technical-service agreements, which impose high fees per barrel on the government at a time when oil prices are low and fail to incentivize oil companies to make cost-effective infrastructure investments. Additionally, accelerating decision-making processes and strengthening institutional capacity are critical to sustaining and expanding international investment in the sector.

Public Sector Transformation

In order to incentivize public sector personnel to switch to the private segment, the government will need to limit the exceedingly large retirement funds and use those funds to start a pension system for private sector workers. Matching the remunerations accessible to public and private segment workers is vital to decrease the huge burden placed on the public accounts by an overstuffed public sector that is presently seen as a lifetime financial assurance for the people who work in it.

Regulatory Transformation

Streamlining the legal stages for opening and running a business, as well as check and balance on bureaucrats who threaten local businesses, might prove an important first step on the way to empowering the private segment to grow. Global investment in Iraq can be considerably assisted by regulatory transformation, a more lenient visa system, and the formation of a higher level commission to support international corporations in traversing the deeply uncooperative administrative system that presently restricts foreign direct investment.

Access to Finance

Countries such as United States, its associates, and global financial institutions can help to increase credit availability by authorizing that a portion of their support goes towards SMEs.

Conclusion

Capital Markets

Iraq's capital markets could be stimulated to develop more. Well-designed capital markets encourage corporate and official transparency, permit both new and established businesses to increase equity and debt capital, simplify new company creation, draw foreign investment, generate wealth, and permit a broad section of the population to part in the country's affluence. Furthermore, well-designed capital markets can have an important part in the growth of critical substructure and post-war rebuilding efforts. Unlisted businesses might be offered tax breaks in exchange for listing on the Iraq Stock Exchange (ISX), and many state-owned organizations might be denationalized and listed on the Exchange. The Iraq Stock Exchange's solvency could be improved further if globally recognized monetary institutions are allowable to act as guardians for securities listed on the ISX.

Bank Transfers

It is important that the government of Iraq should make it easy for overseas corporations to transfer currency into and out of Iraq whereas upholding the integrity of the anti-terrorism-financing, anti-financial crime, and anti-money laundering regime.

References

- Abbott, P. (2017). Iraq must now rebuild itself – and that means fixing its dreadful governance. Metro, 31 July 2017.

- Atlantic Council. (2017). Report of the task force on the future of Iraq: Achieving long-term stability to ensure the defeat of ISIS.

- CIA. (2018). The World Facebook: Iraq.

- Hadad, H. (2017). Doing business in Iraq: On track to wider economic reform. Iraqi Economists Network, Economic Policy Papers.

- Hiltermann, J. (2017). The Kurds are right back where they started. The Atlantic, 31 July 2017.

- Krishnan, N., Olivieri, S., & Lima, L. (2014). IRAQ: The unfulfilled promise of oil and growth - Poverty, inclusion and welfare in Iraq, 2007-2012. The World Bank.

- Mansour, R. (2018). Rebuilding the Iraqi state: Stabilisation, governance and reconciliation. European Parliament, Directorate General for External Policies.

- RoI. (2014). Private sector development strategy 2014-2030. Republic of Iraq.

- Rohwerder, B. (2015). Poverty eradication in Iraq (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1259). Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Sassoon, J. (2012). Economic lessons from Iraq for countries of the Arab Spring. Middle East Program Occasional Paper Series, Woodrow Wilson Centre.

- Sassoon, J. (2014). Iraq: Tackling corruption and sectarianism is more critical than the outcome of elections. Viewpoints, 53, Woodrow Wilson Centre.

- Tabaqchali, A. (2017). Iraq’s economy after ISIS: An investor’s perspective. Institute of Regional and International Studies (IRIS).

- Twaij, A. (2016). Iraq’s year zero: How the free market failed Iraq’s economy’. Middle East Eye, 26 July 2016.

- Yousif, B. (2016). Iraq’s stunted growth: Human and economic development in perspective. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 9(2), 212-236.

- World Bank. (WB). (2012). Private sector development in Iraq: An investment climate reform agenda. MENA Quick Notes Series. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- WB. (2016). Kurdistan region of Iraq: Reforming the economy for shared prosperity and protecting the vulnerable. Executive Summary. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- WB. (2017). Iraq - Systematic Country Diagnostic (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- WB. (2018a). Iraq Economic Outlook-Spring 2018 (English). MENA Economic Outlook Brief. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- WB. (2018b). Doing business 2018: Reforming to create jobs. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.