Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 1

Propensity to Engage in Youth Entrepreneurship in the Face of Covid-19: The case of Klaarwater Township

Thokozani Patmond Mbhele, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Lunga Innocent Qhwagi, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Citation Information: Mbhele T.P., Qhwagi L.I (2023). Propensity to engage in youth entrepreneurship in the face of covid-19: The case of Klaarwater Township. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(1), 1-17.

Abstract

Informal enterprises play a pivotal role in sustaining unemployed youth in impoverished township communities. This qualitative, exploratory study aimed to identify the challenges and opportunities of young entrepreneurs in Klaarwater Township during the Covid-19 pandemic. The research objectives were to identify the socio-economic and supply chain operational challenges experienced by young entrepreneurs in townships; to examine sociodemographic factorsâÂÂ?ÂÂ? influence on their propensity to engage in entrepreneurial practices; and to establish the role of government interventions in increasing trade and propensity to engage in entrepreneurial activities. The sample consisted of seven shops run by young entrepreneurs and 42 regular customers. The interpretivism philosophy was adopted and semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were conducted to gather data that was analysed by means of thematic analysis. The study revealed that the major challenges confronting young entrepreneurs in Klaarwater are the failure of businesses in the area, economic challenges, lack of support, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, and differentiation in goods and services produced. Based on these findings, it is recommended that government; angels and venture capitalists step up their efforts to support young aspiring entrepreneurs.

Keywords

Youth Entrepreneurship, Informal Sector, Challenges, Opportunities, Unemployment

Introduction

A better life for all is the primary goal of post-apartheid South Africa. While the democratic government has passed legislation to promote equality and protect the rights of all citizens, the youth in the densely populated townships and rural areas lack access to higher education and training and meaningful involvement in economic activities. Youth entrepreneurship has been promoted by a variety of practitioners as one solution to these challenges. (Mefi & Asoba, 2020) define entrepreneurship as “innovation through the provision of new goods, new production methods, and the penetration of new markets, the determination of new sources of supply of goods and services or the formation of new organisations”.

For their part, (Dzomonda & Fatoki, 2019) describe entrepreneurship “as the process of conceptualising, organising, launching and through innovation, nurturing a business opportunity into a potentially high growth venture in a complex and unstable environment”. However, identification of gaps in the market calls for socio-economic inclusion and the allocation and effective use of resources. It is against this background that this research focuses on the challenges confronted by township youth who opt to follow the entrepreneurship route. In line with the National Youth Commission (2002) Act and the National Youth Development Policy Framework, the National Youth Commission (NYC) defines the youth as “those falling within the age group of 14 to 35 years, consistent with that of the African Youth Charter (2006)” (Charter, 2006).

This study adopted Statistics South Africa’s (Stats SA) definition of the youth as “persons aged between 15–34”. It is also essential to describe Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs) that have contributed significantly to the growth of the South African economy. The country’s Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) observes a very broad range of firms, some of which includes formally registered, informal and non-VAT registered organisations.

Background of The Study

The study focused on the challenges confronting the youth’s entrepreneurial ventures in Klaarwater, a relatively small township in the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. (StatSA, 2019) estimates a youth unemployment rate in eThekwini Municipality of approximately 39%. Klaarwater is located on the outskirts of Pinetown, relatively close to industrial areas and big retail chains. The ever-increasing price of petrol means that residents spend a significant portion of their income commuting relatively short distances for work and shopping. A taxi to Pinetown, the most used method of transportation in the area, costs R17. This suggests that there is potential for entrepreneurial activities within the township that would enable residents to buy basic necessities locally. This study cogitates on the challenges and opportunities facing young entrepreneurs by modelling supply chain management practices in Klaarwater and suggesting ways to overcome these challenges to enable township businesses to thrive. It also examines government interventions that seek to promote trade in South Africa's townships.

The Covid-19 pandemic has negatively affected economies around the world and South Africa is no exception. The lockdowns imposed in response to the pandemic have crippled many business operations. Against the backdrop of Covid-19 lockdowns as well as the unrest and looting in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng in July 2021 that dealt a R50 billion blow to the economy, South Africa's unemployment rate rose to 34.9% in the third quarter of 2021. Under the expanded definition of unemployment, which includes people who have stopped looking for work, the rate stood at 46.6%, up from 44.4% in the second quarter. The youth unemployment rate that covers job-seekers between the ages of 15 and 34, hit a record high of 66.5% (StatsSA, 2021). Combined with water and electricity load-shedding, Covid-19 and civil unrest severely dented business and investor confidence. Between June and September 2021, the composite leading business cycle indicator, which measures economic activity, deteriorated by more than 5% (StatSA, 2021).

Research Problem and Objectives

South Africa’s high youth unemployment rate suggests that the country’s townships have an abundance of neglected talent and potential for the development of emerging markets in the mainstream economy. As in other townships, Klaarwater’s unemployed youth are drawn into unsavoury, sometimes criminal activities.

It is against this background that the study aimed to identify the challenges and opportunities that young entrepreneurs face by modelling supply chain operational challenges to invigorate trade in the township. It also examined the extent to which sociodemographic factors influence propensity to engage in entrepreneurial practices amongst the youth in South African townships and the role of government interventions in increasing trade and such propensity.

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial Township Economy

In general, townships lack the infrastructure and other resources required to drive sustainable businesses that can assist in addressing the unemployment crisis. As a developing economy, South Africa needs to address unemployment and draw more people into the labour force. StatsSA defines the labour force as the total number of employed and unemployed persons who fall within the working age (15 to 64 years). In turn, (StatsSA, 2019) defines unemployed persons as “those (aged 15–64 years) who: (a) Fall under official unemployment (searched and available); and (b) were available to work but are/or discouraged work-seekers or have other reasons for not searching”.

In general, townships are located on the outskirts of cities in underdeveloped areas that lack infrastructure (Mampheu, 2019) and offer limited employment opportunities. (Cant & Rabie, 2018) describe a township economy as “the micro-economic and related activities occurring within townships”. It incorporates a variety of different shops and business models from hair salons to car washes, builders and associated services, as well as small convenience shops (known as spaza shops) mainly owned by local residents. Entrepreneurship is the key to transforming society and an upsurge in trade in townships would build youth entrepreneurship and small businesses (Manyaka-Boshielo, 2017; Hare, 2017).

Formal and Informal Economy

The term informal sector, also known as the ‘hidden economy’, ‘underground economy’ or ‘shadow economy’, is used to describe a heterogeneous group of economic arrangements (Medina & Schneider, 2018; Mutukwa & Tanyanyiwa, 2021). It is associated with urbanisation in developing countries, coupled with increasing unemployment and low incomes. Despite government attempts to regulate them, informal township entrepreneurs often avoid paying taxes and social security contributions (Mutukwa & Tanyanyiwa, 2021). The informal sector has become the sole source of livelihood for millions of townships residents who are unemployed. Informal activities in South African townships include hawking, trade, craftsmanship, manufacturing, hospitality, and services such as landscaping, shisa’nyama, mini bus/uberization, beauty salons and repairs. Street vendors sell products such as vegetables, fruit, cigarettes, air-time, clothes, shoes, jewellery and cool drinks. Informal enterprises can be categorised as subsistence, survivalist (day-to-day income for survival) or growth-oriented enterprises (Grimm et al., 2012). According to (Rogerson, 2018), survival enterprises operate in areas with low market potential (township areas), whereas growth-oriented enterprises emerge in areas where there is greater economic potential (usually in inner cities).

Perspectives of the Township Economy

Limited access to critical resources such as higher and technical education, private land for business, technology (fibre and broadband) and credit (accessible finance) restricts opportunities for business growth. The dualist perspective adopts a positive view of the informal sector, emphasising its potential to create employment opportunities in developing countries (Wamuthenya, 2009). Economic dualism acknowledges the realities of inequality and unemployment in South Africa, where those that are unable to find work in the fofrmal sector turn to entrepreneurial activities in the informal sector. While informal enterprises are small, they have a remarkable impact on poverty and youth unemployment (Fourie, 2018; Cichello & Rogan, 2018). In contrast, the structuralist perspective focuses on the vulnerability of the informal sector and posits that it resulted from an incomplete transition to advanced capitalism (Wamuthenya, 2009). It employs those who are the most socially and economically vulnerable and serve the interests of capitalist production in the formal sector (Peterson & Lewis, 2001). Therefore, according to structuralists, the informal sector is dominated by a passive and exploited majority that is not able to achieve any real growth or accumulate wealth (Mutukwa & Tanyanyiwa, 2021). Finally, the legalist perspective notes that the poor cannot afford the costs and bureaucracy of registering their enterprises and hence choose to operate in spaces of repressive tolerance by the authorities (Rakowski, 1994).

Theoretical Framework

The study was underpinned by the social exclusion theory that offers deep insight into informal enterprises’ marginalisation and explains the effect of interlinking and mutually reinforcing problems such as unemployment, inequality, a lack of skills, incomes below the living wage and crime, as well as government policies that lead to social and economic exclusion (Rogerson, 2018). Human capital theory focuses on the human subject in an enterprise who takes charge of economic activities such as production, consumption, and transactions (Viljoen & Ledingoane, 2020). Human capital consists of different types of skills like personal, technical, entrepreneurial, business operations and management skills that can be acquired through education and training (Kondowe, 2013). In most cases, informal enterprises’ owners, managers, supervisors, and employees do not possess the education and skills required to perform critical tasks. This constrains the growth of these enterprises (Komin et al., 2021). The study also drew on the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model. Widely accepted for its comprehensiveness, (Heizer et al., 2020) state that the SCOR model is “a set of practices, metrics, and best practices”. It focuses on the six essential elements required to run a business. The SCOR model is used to guide businesses in every stage of the provision of value to consumers. The term supply chain management (SCM), which was coined in the 1980s, refers to “a set of practices for managing and coordinating the transformational activities from raw material suppliers to ultimate customers” (Aziz et al., 2018). It thus, covers all activities from the acquisition of raw materials to consumers’ consumption of finished goods and services. It has evolved over the years from focusing on manufacturing to include linkages between other aspects of business such as marketing, finance, and customer support, and has become a key focus for businesses aiming to thrive in harsh modern-day markets (Hugos, 2018).

Elements of the Framework

Entrepreneurs need to form relationships with suppliers and customers to ensure a smooth flow of information, money, and goods. The networks they form enable effecting planning, sourcing, production, delivery, and management of post-purchase requirements. Modelling trade in the township through SCM practices enabled in-depth exploration of the various factors that influence a firm’s ability to maximise the value provided to the customer. The SCOR model allows firms to modify or remodel their processes and establish and set quantified performance measurements, and provides guidelines on best practices to improve the management of supply chain operations. Planning refers to an analytical procedure that draws on all business information to coordinate the running of the business in terms of demand and supply. In the context of supply chains in the township, the dynamism of modern-day business markets requires higher levels of intricacy when planning to ensure continued improvement in quality and responsiveness to market demand (Aziz et al., 2018) in order to enhance market competitiveness and attract consumers. Sourcing refers to all activities performed to acquire the necessary resources. (Georgise et al., 2017) describe it as the processes involved in scheduling and/or acquisition of the goods and services required by a business. Township enterprises need to maximise the value delivered to customers as well as their profit and sound procurement processes ensure a smooth, consistent supply as well as sustainable benefits (Van den Brink et al., 2019).

Make refers to the production of goods and services. (Heizer et al., 2020) define operations management as the “set of activities that relate to the creation of goods and services through the transformation of inputs into outputs". Based on the resources available, the shop owner needs to decide whether to make the goods or buy them from a wholesaler. Deliver focuses on all activities involved in the movement of goods and services from the business to customers and typically includes managing orders, transportation and distribution. However, in a township economy, a lack of funds and resources means that entrepreneurs may not be able to deliver goods to customers. Return refers to the handling of goods returned by customers and goods returned by the business to its suppliers. It includes authorizing, scheduling, receiving, verifying, disposing of and replacement or credit for such. Although reverse logistics create additional business opportunities, the broader context should be understood from the perspective of recycling and sustainability.

The enable concept encompasses support and governance of all supply chain processes relating to efficiency. SCOR model associated these dimensions such as cost management, asset management, agility, responsiveness, and reliability. Managing costs effectively across the supply chain can yield positive results not only for the firms in the network but also for consumers of the final goods and services. Management of these assets entails strategically aligning them to improve cost saving and increase potential earnings (Suprayitno & Soemitro, 2018). These elements are underpinned by the concept of agility that refers to the rate at which a firm can respond to disturbances in its supply chain. (Fayezi et al., 2017) describe supply chain agility as “a strategic ability that assists organizations rapidly to sense and respond to internal and external uncertainties via effective integration of supply chain relationships”. Disruptions in a supply chain require agility that allows the firm to adjust relatively quickly to any changes that may occur externally. It links with market volatility that refers to a firm’s need for adequate market knowledge, skills, resources, and capacity to firstly respond quickly to changes to minimise the effects of disturbances and secondly, enable it to operate in the new conditions without hampering its ability to provide value to its customers (Gunasekaran et al., 2008). Township businesses further require responsiveness that denotes a supply chain’s ability to identify changes in the market and speedily adapt to avoid affecting the value provided to customers. Reliability connotes consistence and trustworthiness for an uninterrupted supply and maximum customer value (Mampheu, 2019).

Finally, various laws and regulations govern the operation of businesses. According to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), they include those that aim to protect the rights of consumers such as the South African National Consumer Protection Act (CPA) of 2011 and laws that protect firms.

The South African government has taken urgent steps to address unemployment. In 2018, Cabinet approved a R2.1 billion injection into the Small Enterprise Development Fund for the 2019/ 2020 period. The Department of Small Business Development offers grants of up to R1 million to the owners of approved small enterprises, while National Treasury expected to assist more than 2 000 small entities over the period 2018–2020 to redress past inequalities and allocated an estimated R800 million to the Enterprise Development and Entrepreneurship Programme (National Treasury, 2018).

Research Methodology

The key elements of a research methodology are the research philosophy, design, approach, sampling, data collection, and ethical considerations. A research philosophy refers to the logical reasoning used to expand or develop existing knowledge of phenomena (Saunders et al., 2019). This study adopted the epistemological paradigm (Saunders et al., 2019) an exploratory qualitative research approach and an inductive case study research design. Interpretivism was adopted for the inductive approach which aims to achieve rich, in-depth understanding of human perspectives on social problems. The research design provides a logical, structured plan that guides researchers in conducting a study (Pandey & Pandey, 2021). Exploratory research is generally employed when knowledge is limited. Flexibility is required to understand the different dynamics of the phenomenon of youth entrepreneurship. The exploratory qualitative approach in the form of a case study (Rose & Kroese, 2018) assisted in obtaining insight into the youth’s propensity to engage in entrepreneurship in Klaarwater.

Non-probability sampling, where the researchers select the sample based on their subjective judgement, was used in this study. Convenience sampling was employed to select the regular customers and purposive sampling to select the shop owners. Available shop owners and customers in Klaarwater who matched the researchers’ criteria were selected. The criteria were that the shop owners had to be youth between the ages of 15 and 34, and the customers were residents who regularly purchased goods and services from the identified shops. In general, the market is saturated as shops in the area produce and sell the same type of goods and services. For this study, seven youth-owned businesses were identified and 42 regular customers (six per shop), making a total of 49 participants. [Owner shop A to G with six customers per shop and total of 49 = 7x7]. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, time and safety concerns limited the number of participants. Qualitative data collection methods included individual/ mail/ telephonic interviews, and seven focus group discussions. The researchers obtained ethical clearance from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Ethics Committee and permission by means of a gatekeeper’s letter from Klaarwater’s serving ward councillor and the individual entrepreneurs. The participants signed informed consent forms after having been briefed on the purpose and nature of the study. Their rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality were upheld by assigning pseudonyms to each participant and business.

Saturation

In ensuring the quality of the data collected, researchers need to employ exhaustive measures to collect sufficient data on the research topic. (Walker, 2012) argues that, with regard to qualitative data, saturation is reached when no more can be absorbed from the data. (Guest et al., 2020) note that, “In this broader sense, saturation is often described as the point in data collection and analysis when new incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research question”. According to (Lowe et al., 2018) saturation of qualitative data includes, “Thematic saturation that is achieved when further observations and analysis reveal no new themes. Theoretical saturation occurs when additional data cannot further develop qualitative theory derived from the data.”

While saturation raises questions about whether a study has a sufficient number of participants to provide sufficient data, qualitative studies are more concerned with the richness and depth of the data than its volume. From a thematic perspective, recurring themes emerged from discussions with the participants.

Data Analysis and Presentation

Data analysis involves interpreting and logically sorting the data to show relationships between the variables (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Thematic analysis was employed to analyse the data gathered for this study. (Kiger & Varpio, 2020) note that this is a methodical approach to review, interpret, and identify patterns in the data. (Maguire & Delahunt, 2017) state that thematic analysis creates an organised view of the data that enables a researcher to present a cohesive body of information. As recommended by (Makanyeza, 2015), the following steps were followed:

Phase one - Familiarise yourself with the data collected. This involved reading the transcripts and listening to the audio recordings of the focus group discussions and interviews. Using both the transcripts and the recordings ensured that responses were captured accurately.

Phase two - Clean the data. Involves reducing the volume of data by selecting data that is relevant to the research problem and identifying and categorising recurring sentiments expressed by the participants. Microsoft Excel and NVivo version 12 were used to organise and present the data to depict relationships between the variables.

Phase three - Categorise data. This entails re-reading the transcripts and playing back audio recordings to identify patterns and themes in the data. The links found within the data enable it to be interpreted in a logical and meaningful way.

Phase four - Identification of major themes and subtopics. The researchers reviewed the data in line with the research questions to uncover the major themes in the participants' responses. A further review revealed subtopics within each of the major themes.

Phase five - Interpretation of themes and sub-themes. The final step requires the researcher to use the themes and subtopics to present the study’s findings.

The profile of participants and enterprises show that Shop A offers a grass cutting and lawn maintenance service in and around Klaarwater. The owner (32 years) is a qualified, employed teacher, who employs two people. Shop B is a spaza shop (convenience store) along the main road in Klaarwater which the owner inherited from her grandfather. Shop C offers photography/ videography services and sound equipment for sale and hire for events such as weddings, church ceremonies, parties, and other social gatherings.

It is run by a 23-year-old sound engineering student to earn “pocket money.” Shop D sells fast food and its owner was previously employed at a popular franchise in Durban. Shop E is owned and run from home by a 27-year-old seamstress who is a recent fashion studies graduate. It makes church uniforms and outfits for weddings and graduations, as well as alters clothes. Shop F is a construction and renovations business that has been operating for approximately five years. Its owner (34) was previously employed as a roofer for a well-established construction company. Shop G consists of two complementary businesses.

It began as a car wash in an abandoned resource centre along the main road. A popular spot frequented by taxi drivers for its affordable, quality service, it attracts customers from neighbouring communities. In 2019, the owner (30) opened a fast-food business on the same premises. Customers of the car wash can enjoy a meal while their car is being washed. Owner A is a qualified teacher and holds a university degree. Owners B, D, and F have not studied beyond high school. Owner C is currently studying towards a college diploma and Owner E have a college diploma. Owner G trained as a roofer after high school.

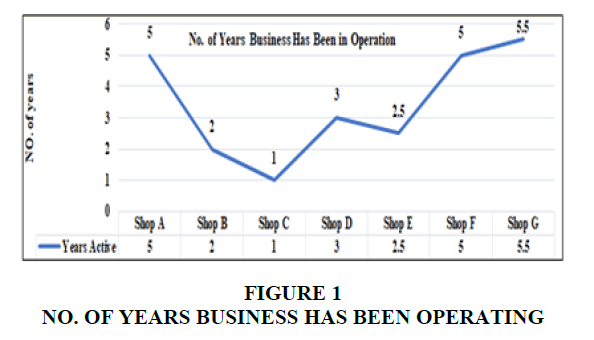

Figure 1 above shows that Shop G had been operating for approximately five-and-a-half years, making it the longest operating business among the seven shops that were sampled. Shops A and F had been operating for five years, while Shop D had been in existence for three years; Shop E for two-and-a-half years; Shop B for two years; and Shop C for one year.

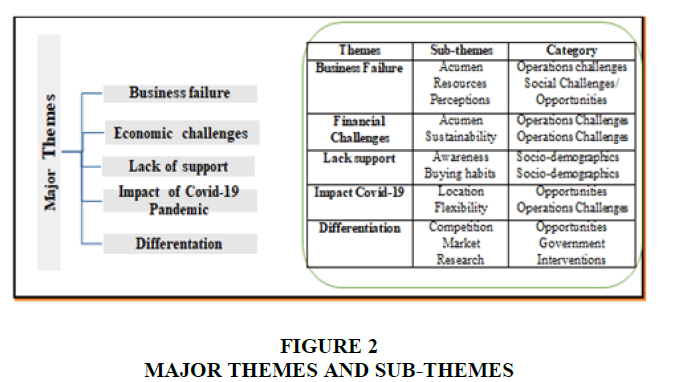

The data analysis identified five major themes, namely, (1) failure of businesses in the area, (2) economic challenges, (3) lack of support, (4) impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, and (5) differentiation in goods and services produced. Sub-themes emerged for each of the major themes. Figure 2 below, produced by NVivo presents the major themes and sub-themes identified during the thematic analysis of the data.

The participants’ views on each of these themes are presented below, quoting the views of individual participants where possible. In a scenario where there was overwhelming consensus, the views of the collective are quoted, be they those of the entrepreneurs or of one or more groups from the seven focus group discussions.

Theme 1 – Business Failure

In response to question 19 in the interviews: Please describe your plan to keep the business running in the foreseeable future; the entrepreneurs expressed concern over the apparent failure of businesses in the area. Owner C remarked: “It is obviously discouraging to see businesses suffer and fail one after the next. Most of the people who start businesses here (Klaarwater) do so because they really do not have any other option. There are no jobs in South Africa. For those who have jobs, the wage or salary they receive is not enough to live the kind of life we all want to live”. Such failure was ascribed to a lack of resources, including capital, physical premises, or the location of shops and inadequate support from the government. Owner A described the pressure as being overwhelming at times. According to Owner B, “it’s difficult to plan ahead when you don’t have money to grow your business. We have families to take care of and we are expected to succeed. Alternatively, you have to somehow find a job to provide for your family”. In response to the question posed to customers in the focus group discussions: What are the challenges that you have experienced in transacting with the businesses in the community? Groups 1 and 4 stated that business failure is due to shop owners’ lack of knowledge, while Group 4 added that, “The problem is that the shop owners in the area are too casual in the way that they run their businesses. We often see crowds of people casually chatting and standing around the entrance of the shops which blocks the entrance. Now, as a customer looking to purchase something, it can be very annoying to try and weave your way through the crowds. It also paints an unfavourable image. We are all aware of some of the social ills that plague our community and so to see scores of mostly young people aimlessly wandering around raises questions about the legitimacy of the businesses. Maybe if the shop owners knew how to run businesses in a way that paints a good image, things would be better”. This group also claimed that on many occasions they wanted to purchase a particular item, only to be told that it was out of stock. This negatively affects perceptions of the shop and drives customers to competitors who, in some cases, are the “foreign-owned spazas and other big retail chains looking to cash in on the deprived townships”.

Theme 2 – Economic challenges

Capital is required to start a business and a prospective business owner would usually approach a bank or government agency for assistance. In response to question 4 in the interviews: Please describe how easy/ difficult it was to obtain start-up capital for your business, shop owners in Klaarwater agreed that it is difficult to raise sufficient capital and also lamented the cost of procuring goods that affects the price customers pay. Owner E stated: “We’re taking knocks on our profit margin (De Lannoy et al., 2018). We pay a lot of money to acquire the goods we sell. Some of us pay for rent, security and still have to invest in our shops to make them attractive to the customers. It takes money to make money, and if you don’t have money, you will not survive in business.” While some shop owners are employed and run their businesses to obtain extra income, several depend solely on their businesses for survival.

In response to question 2 in the focus group discussions: What makes “Business A” your preferred shop over the rest of the businesses in the community?A participant in Group 6 stated, “I understand that they need to charge prices in line with the market. However, one would assume that their geographical location, i.e., the township, would result in lower prices being charged than that of the shops in the affluent suburbs we work in. This is the reason we sometimes choose to shop at the well-established shops in town as they sometimes offer specials and have their in-house brands which are usually more affordable for us”. Thus, on one end of the spectrum, the entrepreneurs claimed that they were not making as much profit as they should while, on the other end, customers were frustrated by the price difference between shops in the area and well-established shops in more affluent suburbs.

Theme 3 – Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic

In response to question 18 in the interviews: How has the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown regulations set out by the government affected the day-to-day running of your business? Owner D stated that, “The lockdowns were a challenge for businesses. I run a shop on the main road in Klaarwater and generally benefit from the traffic around the area. The lockdown essentially limited travel, be it for social visits to friends and family or even travel for work. Fewer people travelling meant that I had fewer faces passing my shop on their way to and from work”. However, Owner G commented that, “the restrictions on travel may have been both positive and negative for my business. With fewer people traveling to work every day and generally less money to spend, the car wash business took a knock. In the same breath, my fast-food joint has enjoyed a lot of success. I think the restrictions meant that people needed to look closer to home for things like takeaways – which was a big plus for me”. In response to question 4 in the focus group discussions: What are the challenges that you have experienced in transacting with the businesses in the community? Customers were divided on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on trade in Klaarwater. While some groups expressed concern about “inflated prices” and their inability to purchase the goods they need, others were more concerned with the financial effects. Importantly, Group 1 noted that some participants were “working fewer hours” as a result of reduced operations at their place of employment. Group 3 stated that “it has been beneficial to have shops nearby as travel was discouraged.” The entrepreneurs’ responses suggest that the Covid-19 pandemic was a true test of the business’ flexibility. From a strategic perspective, businesses may have benefitted by being in proximity to their customers. On the other side of the spectrum, sourcing of goods may have been negatively impacted. The consumers’ responses suggest that the pandemic negatively affected their buying power.

Theme 4 – Lack of support

In response to question 16 in the interviews: Are you aware of any government initiatives that are aimed at aiding businesses in South African townships? If yes, please describe the shop owners and customers had different ideas on what kind of support businesses require. The entrepreneurs stressed that “support isn’t merely in the form of capital, but also loyalty and appreciation.” Owner D said: “I am not aware of the channels available to me to obtain funding Trading Economics (2020). I have thought about approaching a bank, but I don’t think that I can obtain a loan. That is one of the downsides of being unemployed. You have nothing concrete to show that you’re a functioning member of society”. Further discussion revealed that some shop owners did not recognise what they do, i.e., owning and operating their businesses, as ‘real work’, but as a temporary stop gap. This suggests that they had accepted that their business would not grow into a more profitable establishment in the foreseeable future.

In response to question 5 in the focus group discussions: To what extent do you think the community would like to see these businesses grow? Some customers felt that the shops “are only in it to make a quick buck”. Nonetheless, they added that they support shops in the area and would benefit greatly from their growth. Groups 1, 3, and 7 concurred that, “We support shops in the area. They serve as a close, easily accessible option when you need some items. As it is, if you’re doing groceries and rely on public transport, you end up paying for extra seats to load all your groceries – so of course, we support the shops in the area. We would also like to have big shopping malls, cinemas, restaurants and other businesses like … we see in affluent suburbs. Understandably, that might be something we need to take up with the municipalities and government to allocate more resources to build our towns”. Thus, while entrepreneurs indicated a lack of knowledge of avenues to support their business, the customers stated that they support local shops and would like to see them grow.

Theme 5 – Differentiation in goods and services offered

In response to question 9 in the interviews: What are some of the challenges you experienced in producing/ sourcing the goods you sell? Shop owners were aware of benefits that may arise from offering a wide range of goods and services. Owner C said that “Diversifying offerings is a key consideration for me. The nature of my business and I believe every other business, requires careful attention to what the customer wants and needs. The ability to adjust your offerings may boost sales as you’re able to firstly cater accurately for your customers’ needs, and secondly, reach a wider audience as consumer tastes differ”. Owner G concurred: “I don’t think I would still be running my business if it weren’t for the success that I found in adding new components to my business model. I initially offered a car-washing/ auto-valet service and would always worry that people would complain about the queues as my business became very popular in and around Klaarwater. I then decided to make the wait worthwhile by opening a fast-food joint where clients can enjoy light refreshments while their cars are washed. Making this adjustment made a world of difference.” All the shop owners selected for this study agreed on this issue; however, Owner A expressed his desire to diversify offerings but admitted that he was unsure as to how to incorporate this into his business model.

In response to question 3 in the focus group discussions: To what extent do you believe the businesses in the community meet the demands of the community? The variety in goods and services offered was generally welcomed. Group 3 stated: “the shops provide goods and services that the community needs in their everyday lives. Of course, there is room for more as the basket of goods that we consume has a wide range of goods”. However, there was an apparent disconnect between what the shop owners believe customers need and want, and what the customers expect to be sold in the community to meet their needs and wants. This suggests a lack of adequate research as well as insufficient communication between the two parties.

Discussion Of Results

The thematic data analysis revealed the challenges and opportunities confronting young entrepreneurs in Klaarwater, thus achieving the study’s objectives. Research indicates that starting a business requires a substantial amount of capital. In discussing the challenges faced by informal traders, (Mukwarami & Tengeh, 2017) argue that “access to funding usually presents a major obstacle and the little capital raised usually comes from personal savings and borrowing from friends and relatives. (Mbhele, 2012) indicated that angels’ overriding objectives are often to create employment, promote equity and black empowerment, and develop communities and that venture capital-backed firms are likely to demonstrate higher levels of professionalism and more potential for growth than start-up firms that rely on other types of financing.

The study’s first objective was to identify the socio-economic and supply chain operational challenges experienced by young entrepreneurs in townships. Access to capital is an important resource and could be key in keeping one’s business operational (Mtshali et al., 2017). The findings show that the business owners lacked knowledge of how and where to obtain funding to assist their entrepreneurial pursuits. Some said that they used their income from formal employment to fund their businesses. A lack of capital also meant that they were unable to procure the goods/ services required to meet customers’ expectations. Consumers highlighted a lack of professionalism, amongst other things, as a factor contributing to the failure of businesses in Klaarwater. Inability to ensure a smooth, consistent supply of goods to meet demand may result in out-of-stock situations, which in turn create negative perceptions of the business. From a demand perspective, inability to satisfy market demand may result in lost sales as consumers buy goods and services from one’s competitors. Financial constraints suggest that the businesses in the township may not be able to easily attract new customers and thus need to take every opportunity to create positive perceptions in the eyes of their existing ones. From a supply perspective, businesses are tasked with forming and maintaining meaningful relationships with their suppliers. Without the capital required to consistently procure goods and services, township businesses may miss out on the benefits and/or value achieved through meaningful supply chain networks. The entrepreneurs stressed the need for the community to support their entrepreneurial pursuits instead of the well-established business that threaten their livelihood. The aesthetic appeal of their physical premises, products and services, branding, and corporate identity are all key considerations in creating and enhancing perceptions of quality and value. This creates a sense of trust and may result in repeat purchases and ultimately customer loyalty. Effective management of relationships between businesses and consumers is a strategic tool to maximise the value provided to consumers.

The study’s second objective was to examine the extent to which sociodemographic factors influence the youth’s propensity to engage in entrepreneurial practices in South African townships. The business owners expressed the need to understand their customers’ buying patterns. One noted that many people are unemployed in Klaarwater; thus, customers’ buying power should be a key concern. Consumers also have expectations of the kind of goods they want to purchase and at what price. In raising these points, one owner described entrepreneurship as a “means for survival”. Indeed, five of the seven interviewees indicated that being unemployed and financially challenged drove them to entrepreneurship. Almost all of them cited the need to provide for their families as the factor pushing them towards entrepreneurship. Therefore, several social factors influence the youth’s propensity to engage in entrepreneurship.

The third objective was to determine the role of current government interventions in increasing trade and South African youth’s propensity to engage in entrepreneurship in townships. Development of the informal sector is a key consideration for the government as it makes a significant contribution to South Africa’s GDP. It is therefore critical that the government introduces and continuously improves initiatives to fund entrepreneurs, train and upskill the youth, and reduce unemployment (Etikan & Bala, 2017). The shop owners demonstrated limited knowledge of government initiatives aimed at developing SMMEs. They expressed interest in acquiring knowledge on how to decide on what items to make/ buy and how to obtain insight into markets before taking on the risk of introducing new offerings. Angels’ involvement could thus promote professional management of SMMEs (Mbhele, 2012). Some owners expressed the need for mentors, especially in the early stages of one’s entrepreneurial journey. Skills training would benefit those with no background in running a business, market considerations and core business functions. Skills and development opportunities would enhance the shop owners’ business acumen and equip them with skills to identify and present their Unique Selling Proposition (USP) to enhance their competitiveness.

Emerging Factors

The entrepreneurs alluded to concerns over not being able to attract customers as a result of the environment in which they operate. Townships in South Africa are generally densely populated and have been marred by service delivery protests. The entrepreneurs noted that negative perceptions created by media reports undermine the growth of the township economy. Clear distinctions were made between businesses operating in townships and those in neighbouring suburbs that are largely situated in business districts, giving them greater exposure to consumers and making them easily accessible via different modes of transport. Shop owners were also concerned about inconsistent service delivery in the township, including sporadic power outages and water supply disruptions. Supply chains rely on a consistent flow of goods and services. Ideally, businesses should service consumers as and when goods are required. Supply chain disruptions may lead to extended lead times, additional costs to find alternative solutions, stock-outs, and ultimately, unhappy consumers. Power outages and disruptions in water supply challenge shop owners who generally do not have alternatives such as generators and water reserves. The shop owners further highlighted that the lack of infrastructure would likely hinder the growth of township businesses.

The shop owners felt that the geographical position, resources, demographics, and size of the population in the township do not appeal to investors. This suggests that, while there may be a plethora of business ideas, aspiring entrepreneurs do not have confidence in the success of those ideas. Entrepreneurship entails identifying and exploiting gaps in the market.

Finally, several shop owners expressed concern that a number of businesses offer similar goods and services in the community and claimed that this would limit their growth. While competition is healthy for any market, businesses need to be wary of saturation. The threat of saturation may spur innovation to continuously improve existing goods and services.

Contributions of the Study

The study contributes to theory development in the sense that it found that a lack of adequate SCM functions such as planning, communication, and information sharing contributed to the owners’ uncertainty about the future of their businesses. Furthermore, some shop owners did not recognise the need to market and position their businesses to attract customers.

Multiple perspectives were gained by sampling different business models for greater representation of businesses at the study site. Sustainability is also affected by businesses’ relationships with their customers and consumers felt that the businesses in the township need to improve customer relationship management (Starzyczná et al., 2017). Meeting and exceeding customer expectations creates positive perceptions which in turn may result in repeat purchases and customer loyalty.

In conclusion, the challenges confronted by young entrepreneurs call for united efforts on the part of the government, entrepreneurs, and the communities that SMMEs serve. Township businesses need to take advantage of resources such as their location. The fact that they are in close proximity and generally does not incur rental costs leads to cost savings that can be used for other business needs. Barriers to success need to be addressed to promote and develop the township economy. The development of SMMEs is a key focus for the government. The study found that the entrepreneurs lack awareness of funding avenues and other government initiatives aimed at empowering such enterprises. Technological advances have made it relatively easier to communicate and engage target audiences through cost-effective channels such as social media. Big retailers typically keep a database of their customers through subscriptions and issue newsletters and promotional content. While the shops in Klaarwater may not be able to offer discounted sales and regular promotional activities, social media has served some entrepreneurs well.

Data Quality Control

Data quality control refers to efforts that are made by the researcher to ensure that the data collection instrument used to collect data performs correctly and consistently (Korstjens & Moser, 2018). There are four main quality control measures in qualitative research, namely, credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Noble & Smith, 2015). Credibility refers to confidence that a researcher’s findings accurately represent the views and opinions expressed by respondents (Cameron, 2011). (Maher et al., 2018) assert that “credibility ensures the study measures what is intended and is a true reflection of the social reality of the participants”. (Noble & Smith, 2015) define transferability as the extent to which the research design, questions, and tools can be transferred or applied to a different study setting. (Korstjens & Moser, 2018) state that dependability relates to consistency and expresses the degree to which a study may produce consistent findings when repeated.

The confirmability relates to objectivity and expresses the extent to which similar findings may be obtained or validated by a different researcher. Credibility and dependability of the findings were ensured through (1) note-taking during discussions, (2) summarising discussions with participants at the end of interviews and focus group discussions, and (3) repetitive reading of responses.

The questions were translated into the local dialect to promote understanding. Given that economic activity occurs in and across townships in South Africa and abroad, the design, questions and data collection tools used in this study are applicable across multiple study settings. Furthermore, different sources of information were used to gain greater insight into the research problem. The secondary data was sourced from the literature on the research topic and primary data was obtained from the seven interviews and seven focus group discussions. The same questions were posed to all interviewees and focus group participants, ensuring the credibility of the findings. The use of multiple data sources and data collection, known as triangulation, promotes knowledge development and enhances understanding of phenomena (Fusch et al., 2018).

Concluding Remarks

The study unveiled the challenges that young entrepreneurs face in South African townships as well as inherent opportunities that may not only positively influence propensity to engage in entrepreneurship among young people, but also invigorate trade in the townships. While it is acknowledged that entrepreneurs need to empower themselves with skills and knowledge, the role of the government cannot be understated. Unemployment, especially among the youth, has reached alarming proportions in South Africa and employment opportunities are the best defence against widespread poverty.

Entrepreneurship not only offers an opportunity to generate a sustainable income but also allows for the creation of further employment opportunities. There is a need to investigate the effectiveness of government initiatives to encourage and equip aspiring entrepreneurs with the mix of skills, information, and resources required to succeed in the modern-day economy.

Entrepreneurship not only offers an opportunity to generate a sustainable income but also allows for the creation of further employment opportunities. There is a need to investigate the effectiveness of government initiatives to encourage and equip aspiring entrepreneurs with the mix of skills, information, and resources required to succeed in the modern-day economy.

The study further emphasized the need for businesses to understand the markets in which they operate as this contributes to effective planning, sourcing, and delivery of value that meets and/or exceeds customer expectations.

References

Aziz, M.A., Ragheb, M.A., Ragab, A.A., & El Mokadem, M. (2018). The impact of enterprise resource planning on supply chain management practices. The Business & Management Review, 9(4), 56-69.

Cameron, R. (2011). An analysis of quality criteria for qualitative research. In 25th ANZAM Conference (pp. 2-16).

Cant, M.C., & Rabie, C. (2018). Township SMME sustainability: a South African perspective. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 14(7).

Charter, A.Y. (2006). Adopted by the seventh ordinary session of the assembly, held in Banjul. The Gambia On 2nd July.

Cichello, P. & Rogan, M. (2018). Informal-sector employment and poverty reduction in South Africa: The contribution of “informal” sources of income, in F.C.v.N. Fourie (ed.)

De Lannoy, A., Graham, L., Patel, L., & Leibbrandt, M. (2018). What drives youth unemployment and what interventions help. High-level Overview Report.

Dzomonda, O., & Fatoki, O. (2019). The role of institutions of higher learning towards youth entrepreneurship development in South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 25(1), 1-11.

Etikan, I., & Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 5(6), 00149.

Fayezi, S., Zutshi, A., & O'Loughlin, A. (2017). Understanding and development of supply chain agility and flexibility: a structured literature review. International journal of management reviews, 19(4), 379-407.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fourie, F. (2018). Analysing the informal sector in South Africa: Knowledge and policy gaps, conceptual and data challenges. The South African informal sector: Creating jobs, reducing poverty, 1-22.

Fusch, P., Fusch, G.E., & Ness, L.R. (2018). Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. Journal of social change, 10(1), 2.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Georgise, F.B., Wuest, T., & Thoben, K.D. (2017). SCOR model application in developing countries: challenges & requirements. Production Planning & Control, 28(1), 17-32.

Grimm, M., Knorringa, P., & Lay, J. (2012). Constrained gazelles: High potentials in West Africa’s informal economy. World Development, 40(7), 1352-1368.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PloS one, 15(5), e0232076.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gunasekaran, A., Lai, K.H., & Cheng, T.E. (2008). Responsive supply chain: a competitive strategy in a networked economy. Omega, 36(4), 549-564.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Heizer, J., Render, B., Munson, C., & Sachan, A. (2020). Operations management: sustainability and supply chain management, 12/e.

Hugos, M.H. (2018). Essentials of supply chain management. John Wiley & Sons.

Kiger, M.E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical teacher, 42(8), 846-854.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Komin, W., Thepparp, R., Subsing, B., & Engstrom, D. (2021). Covid-19 and its impact on informal sector workers: a case study of Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 31(1-2), 80-88.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kondowe, C. (2013). Exploring the circumstances and experiences of youth immigrants when establishing and running a successful informal micro-business. (Master's thesis, University of Cape Town).

Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 6: longitudinal qualitative and mixed-methods approaches for longitudinal and complex health themes in primary care research. European Journal of General Practice, 28(1), 118-124.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lowe, A., Norris, A.C., Farris, A.J., & Babbage, D.R. (2018). Quantifying thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. Field methods, 30(3), 191-207.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 9(3).

Maher, C., Hadfield, M., Hutchings, M., & De Eyto, A. (2018). Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: A design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. International journal of qualitative methods, 17(1), 1609406918786362.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Makanyeza, C. (2015). Consumer awareness, ethnocentrism and loyalty: An integrative model. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 27(2), 167-183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mampheu, V. (2019). Entrepreneurial success factors of immigrant spaza-shop owners in Thulamela Local Municipality (Doctoral dissertation).

Manyaka-Boshielo, S.J. (2017). Social entrepreneurship as a way of developing sustainable township economies. HTS: Theological Studies, 73(4), 1-10.

Mbhele, T.P. (2012). The study of venture capital finance and investment behaviour in small and medium-sized enterprises. South African journal of economic and management sciences, 15(1), 94-111.

Medina, L., & Schneider, M.F. (2018).Shadow economies around the world: what did we learn over the last 20 years?. International Monetary Fund.

Mefi, N.P., & Asoba, S.N. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and the sustainability of small businesses at a South African township. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 26(4), 1-11.

Mtshali, M., Mtapuri, O., & Shamase, S.P. (2017). Experiences of black-owned small medium and micro enterprises in the accommodation tourism-sub sector in selected Durban townships, KwaZulu-Natal. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(3), 130-141.

Mukwarami, J., & Tengeh, R.K. (2017). Sustaining native entrepreneurship in South African townships: The start-up agenda. International Economics.

Mutukwa, M.T., & Tanyanyiwa, S. (2021). De-stereotyping Informal Sector Gendered Division of Work: A Case Study of Magaba Home Industry, Harare, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Public Affairs, 12(1), 188-206.

National Treasury, (2018). Vote 31. Small Business Development.

National Youth Commission. (2002). Towards Integrated National Youth Development Initiatives and Programmes. National Youth Development Policy Framework (2002-2007).

Noble, H., & Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-based nursing,18(2), 34-35.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pandey, P., & Pandey, M.M. (2021).Research methodology tools and techniques. Bridge Center.

Peterson, J., & Lewis, M. (Eds.). (2001).The Elgar companion to feminist economics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rakowski, C.A. (1994). Convergence and divergence in the informal sector debate: A focus on Latin America, 1984–92. World development,22(4), 501-516.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rogerson, C.M. (2018). Towards pro-poor local economic development: the case for sectoral targeting in South Africa. InLocal Economic Development in the Developing World(pp. 75-100). Routledge.

Rose, J., & Stenfert Kroese, B. (2018). Introduction to special issue on qualitative research.International Journal of Developmental Disabilities,64(3), 129-131.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students Eight Edition.QualitativeMarket Research: An International Journal.

Starzyczná, H., Pellešová, P., & Stoklasa, M. (2017). The comparison of customer relationship management (CRM) in Czech small and medium enterprises according to selected characteristics in the years 2015, 2010 and 2005.Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis,65(5), 1767-1777.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

StatSA, (2019). Statistical Release P0211. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) Quarter 4: 2019.

StatSA, (2021). Statistical Release P0211, 4th Quarter. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) Quarter 4: 2020.

Suprayitno, H., & Soemitro, R.A.A. (2018). Preliminary Reflexion on Basic Principle of Infrastructure Asset Management.Journal Manajemen Aset Infrastruktur & Fasilitas,2(1).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study.Nursing & health sciences,15(3), 398-405.

Van den Brink, S., Kleijn, R., Tukker, A., & Huisman, J. (2019). Approaches to responsible sourcing in mineral supply chains.Resources, Conservation and Recycling,145, 389-398.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Viljoen, J.M.M. & Ledingoane, C.M. (2020). Employment growth constraints of informal enterprises in Diepsloot, Johannesburg. Acta Commer.(1)20, pp.1-15.

Walker, J.L. (2012). Research column.The Use of Saturation in Qualitative Research.Canadian journal of cardiovascular nursing,22(2).

Wamuthenya, W. (2009). Gender Differences in the Determinants of Formal and Informal Sector Employment in the Urban Areas of Kenya across Time. Paper presented to the 18th IAFFE Conference in Boston, June 25–28, 2009.

Received: 23-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. IJE-22-12342; Editor assigned: 25-Oct-2022, PreQC No. IJE-22-12342(PQ); Reviewed: 08-Nov-2022, QC No. IJE-22-12342; Revised: 14-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. IJE-22-12342(R); Published: 21-Nov-2022